Russian battleship Potemkin

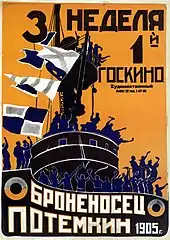

The Russian battleship Potemkin (Russian: Князь Потёмкин Таврический, romanized: Kniaz Potyomkin Tavricheskiy, "Prince Potemkin of Taurida") was a pre-dreadnought battleship built for the Imperial Russian Navy's Black Sea Fleet. She became famous when the crew rebelled against the officers in June 1905 (during that year's revolution), which is now viewed as a first step towards the Russian Revolution of 1917. The mutiny later formed the basis of Sergei Eisenstein's 1925 silent film Battleship Potemkin.

Panteleimon at sea, 1906 | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Operators | |

| Preceded by | Peresvet-class battleship |

| Succeeded by | Russian battleship Retvizan |

| In commission | 1903–1918 |

| Completed | 1 |

| Scrapped | 1 |

| History | |

| Name |

|

| Namesake |

|

| Builder | Nikolaev Admiralty Shipyard |

| Laid down | 10 October 1898[Note 1] |

| Launched | 9 October 1900 |

| Decommissioned | March 1918 |

| In service | Early 1905 |

| Out of service | 19 April 1919 |

| Stricken | 21 November 1925 |

| Fate | Scrapped, 1923 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Pre-dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement |

|

| Length | 378 ft 6 in (115.4 m) |

| Beam | 73 ft (22.3 m) |

| Draught | 27 ft (8.2 m) |

| Installed power | |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts, 2 Vertical triple-expansion steam engines |

| Speed | 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph) |

| Range | 3,200 nautical miles (5,900 km; 3,700 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement | 26 officers, 705 enlisted men |

| Armament |

|

| Armour |

|

After the mutineers sought asylum in Constanța, Romania, and after the Russians recovered the ship, her name was changed to Panteleimon. She accidentally sank a Russian submarine in 1909 and was badly damaged when she ran aground in 1911. During World War I, Panteleimon participated in the Battle of Cape Sarych in late 1914. She covered several bombardments of the Bosphorus fortifications in early 1915, including one where the ship was attacked by the Ottoman battlecruiser Yavuz Sultan Selim – Panteleimon and the other Russian pre-dreadnoughts present drove her off before she could inflict any serious damage. The ship was relegated to secondary roles after Russia's first dreadnought battleship entered service in late 1915. She was by then obsolete and was reduced to reserve in 1918 in Sevastopol.

Panteleimon was captured when the Germans took Sevastopol in May 1918 and was handed over to the Allies after the Armistice in November 1918. Her engines were destroyed by the British in 1919 when they withdrew from Sevastopol to prevent the advancing Bolsheviks from using them against the White Russians. The ship was abandoned when the Whites evacuated the Crimea in 1920 and was finally scrapped by the Soviets in 1923.

Design and construction

Planning

Planning began in 1895 for a new battleship that would utilise a slipway slated to become available at the Nikolayev Admiralty Shipyard in 1896. The Naval Staff and the commander of the Black Sea Fleet, Vice Admiral K. P. Pilkin, agreed on a copy of the Peresvet-class battleship design, but they were over-ruled by General Admiral Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich. The General Admiral decided that the long range and less powerful 10-inch (254 mm) guns of the Peresvet class were inappropriate for the narrow confines of the Black Sea, and ordered the design of an improved version of the battleship Tri Sviatitelia instead. The improvements included a higher forecastle to improve the ship's seakeeping qualities, Krupp cemented armour and Belleville boilers. The design process was complicated by numerous changes demanded by various departments of the Naval Technical Committee. The ship's design was finally approved on 12 June 1897, although design changes continued to be made that slowed the ship's construction.[1]

Construction and sea trials

Construction of Potemkin began on 27 December 1897 and she was laid down at the Nikolayev Admiralty Shipyard on 10 October 1898. She was named in honour of Prince Grigory Potemkin, a Russian soldier and statesman.[2] The ship was launched on 9 October 1900 and transferred to Sevastopol for fitting out on 4 July 1902. She began sea trials in September 1903 and these continued, off and on, until early 1905 when her gun turrets were completed.[3]

Description

Potemkin was 371 feet 5 inches (113.2 m) long at the waterline and 378 feet 6 inches (115.4 m) long overall. She had a beam of 73 feet (22.3 m) and a maximum draught of 27 feet (8.2 m). The battleship displaced 12,900 long tons (13,100 t), 420 long tons (430 t) more than her designed displacement of 12,480 long tons (12,680 t). The ship's crew consisted of 26 officers and 705 enlisted men.[4]

Potemkin had a pair of three-cylinder vertical triple-expansion steam engines, each of which drove one propeller, that had a total designed output of 10,600 indicated horsepower (7,900 kW). Twenty-two Belleville boilers provided steam to the engines at a pressure of 15 atm (1,520 kPa; 220 psi). The 8 boilers in the forward boiler room were oil-fired and the remaining 14 were coal-fired. During her sea trials on 31 October 1903, she reached a top speed of 16.5 knots (30.6 km/h; 19.0 mph). Leaking oil caused a serious fire on 2 January 1904 that caused the navy to convert her boilers to coal firing at a cost of 20,000 rubles. The ship carried a maximum of 1,100 long tons (1,100 t) of coal at full load that provided a range of 3,200 nautical miles (5,900 km; 3,700 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[5]

Armament

The battleship's main battery consisted of four 40-calibre 12-inch (305 mm) guns mounted in twin-gun turrets fore and aft of the superstructure. The electrically operated turrets were derived from the design of those used by the Petropavlovsk-class battleships. These guns had a maximum elevation of +15° and their rate of fire was very slow, only one round every four minutes during gunnery trials.[6] They fired a 745-pound (337.7 kg) shell at a muzzle velocity of 2,792 ft/s (851 m/s). At an elevation of +10° the guns had a range of 13,000 yards (12,000 m).[7] Potemkin carried 60 rounds for each gun.[6]

The sixteen 45-calibre, six-inch (152 mm) Canet Pattern 1891 quick-firing (QF) guns were mounted in casemates. Twelve of these were placed on the sides of the hull and the other four were positioned at the corners of the superstructure.[6] They fired shells that weighed 91.4 lb (41.46 kg) with a muzzle velocity of 2,600 ft/s (792 m/s). They had a maximum range of 12,602 yards (11,523 m) when fired at an elevation of +20°.[8] The ship stowed 160 rounds per gun.[4]

Smaller guns were carried for close-range defence against torpedo boats. These included fourteen 50-calibre Canet QF 75-millimetre (3 in) guns: four in hull embrasures and the remaining ten mounted on the superstructure. Potemkin carried 300 shells for each gun.[6] They fired an 11-pound (4.9 kg) shell at a muzzle velocity of 2,700 ft/s (820 m/s) to a maximum range of 7,005 yards (6,405 m).[9] She also mounted six 47-millimetre (1.9 in) Hotchkiss guns. Four of these were mounted in the fighting top and two on the superstructure.[6] They fired a 2.2-pound (1 kg) shell at a muzzle velocity of 1,400 ft/s (430 m/s).[10]

Potemkin had five underwater 15-inch (381 mm) torpedo tubes: one in the bow and two on each broadside. She carried three torpedoes for each tube.[6] The model of torpedo in use changed over time; the first torpedo that the ship would have been equipped with was the M1904. It had a warhead weight of 150 pounds (70 kg) and a speed of 33 knots (61 km/h; 38 mph) with a maximum range of 870 yards (800 m).[11]

In 1907 telescopic sights were fitted for the 12-inch and 6-inch guns. In that or the following year 2.5-metre (8 ft 2 in) rangefinders were installed. The bow torpedo tube was removed in 1910–1911, as was the fighting top. The following year the main-gun turret machinery was upgraded and the guns were modified to improve their rate of fire to one round every 40 seconds.[12]

Two 57-millimetre (2.2 in) anti-aircraft (AA) guns were mounted on Potemkin's superstructure on 3–6 June 1915; they were supplemented by two 75 mm AA guns, one on top of each turret, probably during 1916. In February 1916 the ship's four remaining torpedo tubes were removed. At some point during World War I, her 75 mm guns were also removed.[13]

Protection

The maximum thickness of the Krupp cemented armour waterline belt was nine inches (229 mm) which reduced to eight inches (203 mm) abreast the magazines. It covered 237 feet (72.2 m) of the ship's length and two-inch (51 mm) plates protected the waterline to the ends of the ship. The belt was 7 feet 6 inches (2.3 m) high, of which 5 feet (2 m) was below the waterline, and tapered down to a thickness of five inches (127 mm) at its bottom edge. The main part of the belt terminated in seven-inch (178 mm) transverse bulkheads.[6]

Above the belt was the upper strake of six-inch armour that was 156 feet (47.5 m) long and closed off by six-inch transverse bulkheads fore and aft. The upper casemate protected the six-inch guns and was five inches thick on all sides. The sides of the turrets were ten inches (254 mm) thick and they had a two-inch roof. The conning tower's sides were nine inches thick. The nickel-steel armour deck was two inches thick on the flat amidships, but 2.5 inches (64 mm) thick on the slope connecting it to the armour belt. Fore and aft of the armoured citadel, the deck was three inches (76 mm) to the bow and stern.[6] In 1910–1911, additional one-inch (25 mm) armour plates were added fore and aft; their exact location is unknown, but they were probably used to extend the height of the two-inch armour strake at the ends of the ship.[12]

Service

Mutiny

During the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905, many of the Black Sea Fleet's most experienced officers and enlisted men were transferred to the ships in the Pacific to replace losses. This left the fleet with primarily raw recruits and less capable officers. With the news of the disastrous Battle of Tsushima in May 1905, morale dropped to an all-time low, and any minor incident could be enough to spark a major catastrophe.[14] Taking advantage of the situation, plus the disruption caused by the ongoing riots and uprisings, the Central Committee of the Social Democratic Organisation of the Black Sea Fleet, called "Tsentralka", had started preparations for a simultaneous mutiny on all of the ships of the fleet, although the timing had not been decided.[15]

On 27 June 1905, Potemkin was at gunnery practice near Tendra Spit off the Ukrainian coast when many enlisted men refused to eat the borscht made from rotten meat infested with maggots. Brought aboard the warship the previous day from shore suppliers, the carcasses had been passed as suitable for eating by the ship's senior surgeon Dr Sergei Smirnov after several perfunctory examinations.[16]

The uprising was triggered when Ippolit Giliarovsky, the ship's second in command, allegedly threatened to shoot crew members for their refusal. He summoned the ship's marine guards as well as a tarpaulin to protect the ship's deck from any blood in an attempt to intimidate the crew. Giliarovsky was killed after he mortally wounded Grigory Vakulinchuk, one of the mutiny's leaders. The mutineers killed seven of the Potemkin's eighteen officers, including Captain Evgeny Golikov (ru), Executive Officer Giliarovsky and Surgeon Smirnov; and captured the accompanying torpedo boat Ismail (No. 267). They organised a ship's committee of 25 sailors, led by Afanasi Matushenko, to run the battleship.[17]

The committee decided to head for Odessa flying a red flag and arrived there later that day at 22:00. A general strike had been called in the city and there was some rioting as police tried to quell the strikers. The following day the mutineers refused to supply a landing party to help the striking revolutionaries take over the city, preferring instead to await the arrival of the other battleships of the Black Sea Fleet. Later that day the mutineers aboard Potemkin captured a military transport, Vekha, that had arrived in the city. The riots continued as much of the port area was destroyed by fire. On the afternoon of 29 June, Vakulinchuk's funeral turned into a political demonstration and the army attempted to ambush the sailors who participated in the funeral. In retaliation, Potemkin fired two six-inch shells at the theatre where a high-level military meeting was scheduled to take place, but missed.[18]

Vice Admiral Grigoriy Chukhnin, commander of the Black Sea Fleet, issued an order to send two squadrons to Odessa either to force Potemkin's crew to give up or sink the battleship. Potemkin sortied on the morning of 30 June to meet the three battleships Tri Sviatitelia, Dvenadsat Apostolov, and Georgii Pobedonosets of the first squadron, but the loyal ships turned away. The second squadron arrived with the battleships Rostislav and Sinop later that morning, and Vice Admiral Aleksander Krieger, acting commander of the Black Sea Fleet, ordered the ships to proceed to Odessa. Potemkin sortied again and sailed through the combined squadrons as Krieger failed to order his ships to fire. Captain Kolands of Dvenadsat Apostolov attempted to ram Potemkin and then detonate his ship's magazines, but he was thwarted by members of his crew. Krieger ordered his ships to fall back, but the crew of Georgii Pobedonosets mutinied and joined Potemkin.[19]

The following morning, loyalist members of Georgii Pobedonosets retook control of the ship and ran her aground in Odessa harbour.[20] The crew of Potemkin, together with Ismail, decided to sail for Constanța later that day where they could restock food, water and coal. The Romanians refused to provide the supplies, backed by the presence of their small protected cruiser Elisabeta, so the ship's committee decided to sail for the small, barely defended port of Theodosia in the Crimea where they hoped to resupply. The ship arrived on the morning of 5 July, but the city's governor refused to give them anything other than food. The mutineers attempted to seize several barges of coal the following morning, but the port's garrison ambushed them and killed or captured 22 of the 30 sailors involved. They decided to return to Constanța that afternoon.[21]

Potemkin reached its destination at 23:00 on 7 July and the Romanians agreed to give asylum to the crew if they would disarm themselves and surrender the battleship. Ismail's crew decided the following morning to return to Sevastopol and turn themselves in, but Potemkin's crew voted to accept the terms. Captain Nicolae Negru, commander of the port, came aboard at noon and hoisted the Romanian flag and then allowed the ship to enter the inner harbor. Before the crew disembarked, Matushenko ordered that Potemkin's Kingston valves be opened so she would sink to the bottom.[22]

Later service

When Rear Admiral Pisarevsky reached Constanța on the morning of 9 July, he found Potemkin half sunk in the harbour and flying the Romanian flag. After several hours of negotiations with the Romanian government, the battleship was handed over to the Russians. Later that day the Russian Navy Ensign was raised over the battleship.[23] She was then easily refloated by the navy, but the salt water had damaged her engines and boilers. The ship left Constanța on 10 July, having to be towed back to Sevastopol, where she arrived on 14 July.[24] The ship was renamed Panteleimon (Russian: Пантелеймон), after Saint Pantaleon,[25] on 12 October 1905. Some members of Panteleimon's crew joined a mutiny that began aboard the protected cruiser Ochakov (ru) in November, but it was easily suppressed as both ships had been earlier disarmed.[24]

Panteleimon received an experimental underwater communications set[26] in February 1909. Later that year, she accidentally rammed and sank the submarine Kambala (ru) at night on 11 June [according to Russian sources, Kambala sank in a collision with Rostislav, not with Panteleimon,[24] killing the 16 crewmen aboard the submarine].[27]

While returning from a port visit to Constanța in 1911, Panteleimon ran aground on 2 October. It took several days to refloat her and make temporary repairs, and the full extent of the damage to its bottom was not fully realised for several more months. The ship participated in training and gunnery exercises for the rest of the year; a special watch was kept to ensure that no damaged seams were opened during firing. Permanent repairs, which involved replacing its boiler foundations, plating, and a large number of its hull frames, lasted from 10 January to 25 April 1912. The navy took advantage of these repairs to overhaul Panteleimon's engines and boilers.[28]

World War I

Panteleimon, flagship of the 1st Battleship Brigade, accompanied by the pre-dreadnoughts Evstafi, Ioann Zlatoust, and Tri Sviatitelia, covered the pre-dreadnought Rostislav while she bombarded Trebizond on the morning of 17 November 1914. They were intercepted the following day by the Ottoman battlecruiser Yavuz Sultan Selim (the ex-German SMS Goeben) and the light cruiser Midilli (the ex-German SMS Breslau) on their return voyage to Sevastopol in what came to be known as the Battle of Cape Sarych. Despite the noon hour the conditions were foggy; the capital ships initially did not spot each other. Although several other ships opened fire, hitting the Yavuz Sultan Selim once, Panteleimon held her fire because her turrets could not see the Ottoman ships before they disengaged.[29]

Tri Sviatitelia and Rostislav bombarded Ottoman fortifications at the mouth of the Bosphorus on 18 March 1915, the first of several attacks intended to divert troops and attention from the ongoing Gallipoli campaign, but fired only 105 rounds before sailing north to rejoin Panteleimon, Ioann Zlatoust and Evstafi.[30] Tri Sviatitelia and Rostislav were intended to repeat the bombardment the following day, but were hindered by heavy fog.[31] On 3 April, Yavuz Sultan Selim and several ships of the Ottoman navy raided the Russian port at Odessa; the Russian battleship squadron sortied to intercept them. The battleships pursued Yavuz Sultan Selim the entire day, but were unable to close to effective gunnery range and were forced to break off the chase.[32] On 25 April Tri Sviatitelia and Rostislav repeated their bombardment of the Bosphorus forts. Tri Sviatitelia, Rostislav and Panteleimon bombarded the forts again on 2 and 3 May. This time a total of 337 main-gun rounds were fired in addition to 528 six-inch shells between the three battleships.[30]

On 9 May 1915, Tri Sviatitelia and Panteleimon returned to bombard the Bosphorus forts, covered by the remaining pre-dreadnoughts. Yavuz Sultan Selim intercepted the three ships of the covering force, although no damage was inflicted by either side. Tri Sviatitelia and Pantelimon rejoined their consorts and the latter scored two hits on Yavuz Sultan Selim before it broke off the action. The Russian ships pursued it for six hours before giving up the chase. On 1 August, all of the Black Sea pre-dreadnoughts were transferred to the 2nd Battleship Brigade, after the more powerful dreadnought Imperatritsa Mariya entered service. On 1 October the new dreadnought provided cover while Ioann Zlatoust and Pantelimon bombarded Zonguldak and Evstafi shelled the nearby town of Kozlu.[13] The ship bombarded Varna twice in October 1915; during the second bombardment on 27 October, she entered Varna Bay and was unsuccessfully attacked by two German submarines stationed there.[33]

Panteleimon supported Russian troops in early 1916 as they captured Trebizond[24] and participated in an anti-shipping sweep off the north-western Anatolian coast in January 1917 that destroyed 39 Ottoman sailing ships.[34] On 13 April 1917, after the February Revolution, the ship was renamed Potemkin-Tavricheskiy (Потёмкин-Таврический), and then on 11 May was renamed Borets za svobodu (Борец за свободу – Freedom Fighter).[24]

Reserve and decommissioning

Borets za Svobodu was placed in reserve in March 1918 and was captured by the Germans at Sevastopol in May. They handed the ship over to the Allies in December 1918 after the Armistice. The British wrecked her engines on 19 April 1919 when they left the Crimea to prevent the advancing Bolsheviks from using her against the White Russians. Thoroughly obsolete by this time, the battleship was captured by both sides during the Russian Civil War, but was abandoned by the White Russians when they evacuated the Crimea in November 1920. Borets za Svobodu was scrapped beginning in 1923, although she was not stricken from the Navy List until 21 November 1925.[24]

Legacy

The immediate effects of the mutiny are difficult to assess. It may have influenced Tsar Nicholas II's decisions to end the Russo-Japanese War and accept the October Manifesto, as the mutiny demonstrated that his régime no longer had the unquestioning loyalty of the military. The mutiny's failure did not stop other revolutionaries from inciting insurrections later that year, including the Sevastopol Uprising. Vladimir Lenin, leader of the Bolshevik Party, called the 1905 Revolution, including the Potemkin mutiny, a "dress rehearsal" for his successful revolution in 1917.[35] The communists seized upon it as a propaganda symbol for their party and unduly emphasised their role in the mutiny. In fact, Matushenko explicitly rejected the Bolsheviks because he and the other leaders of the mutiny were socialists of one type or another and cared nothing for communism.[36]

The mutiny was memorialised most famously by Sergei Eisenstein in his 1925 silent film Battleship Potemkin, although the French silent film La Révolution en Russie (Revolution in Russia or Revolution in Odessa, 1905), directed by Lucien Nonguet was the first film to depict the mutiny,[37] preceding Eisenstein's far more famous film by 20 years. Filmed shortly after the Bolshevik victory in the Russian Civil War of 1917–1922,[36] with the derelict Dvenadsat Apostolov standing in for the broken-up Potemkin,[38] Eisenstein recast the mutiny into a predecessor of the October Revolution of 1917 that swept the Bolsheviks to power. He emphasised their role, and implied that the mutiny failed because Matushenko and the other leaders were not better Bolsheviks. Eisenstein made other changes to dramatise the story, ignoring the major fire that swept through Odessa's dock area while Potemkin was anchored there, combining the many different incidents of rioters and soldiers fighting into a famous sequence on the steps (today known as the Potemkin Stairs), and showing a tarpaulin thrown over the sailors to be executed.[36]

In accordance with the Marxist doctrine that history is made by collective action, not individuals, Eisenstein forbore to single out any person in his film, but rather focused on the "mass protagonist".[39] Soviet film critics hailed this approach, including the dramaturge and critic, Adrian Piotrovsky, writing for the Leningrad newspaper Krasnaia gazeta:

The hero is the sailors' battleship, the Odessa crowd, but characteristic figures are snatched here and there from the crowd. For a moment, like a conjuring trick, they attract all the sympathies of the audience: like the sailor Vakulinchuk, like the young woman and child on the Odessa Steps, but they emerge only to dissolve once more into the mass. This signifies: no film stars but a film of real-life types.[40]

Similarly, theatre critic Alexei Gvozdev wrote in the journal Artistic Life (Zhizn ikusstva):[41] "In Potemkin there is no individual hero as there was in the old theatre. It is the mass that acts: the battleship and its sailors and the city and its population in revolutionary mood."[42]

The last survivor of the mutiny was Ivan Beshoff, who died on 24 October 1987 at the age of 102 in Dublin, Ireland.[43]

Notes

- All dates used in this article are New Style.

References

- McLaughlin 2003, pp. 117–118

- Silverstone, p. 378

- McLaughlin 2003, pp. 116, 121

- McLaughlin 2003, p. 116

- McLaughlin 2003, pp. 116, 119–120

- McLaughlin 2003, p. 119

- Friedman, pp. 251–253

- Friedman, pp. 260–261

- Friedman, p. 264

- Smigielski, p. 160

- Friedman, p. 348

- McLaughlin 2003, pp. 294–295

- McLaughlin 2003, p. 304

- Watts, p. 24

- Bascomb, p. 20–24

- Bascomb, pp. 63–67

- Bascomb, pp. 60–72, 88–94, 96–103

- Bascomb, pp. 55–60, 112–127, 134–153, 164–167, 170–178

- Bascomb, pp. 179–201

- Zebroski, p. 21

- Bascomb, pp. 224–227, 231–247, 252–254, 265–270, 276–281

- Bascomb, pp. 286–299

- Bascomb, p. 297

- McLaughlin 2003, p. 121

- Silverstone, p. 380

- Godin & Palmer, p. 33

- Polmar & Noot, p. 230

- McLaughlin 2003, pp. 120–121, 172, 295

- McLaughlin 2001, pp. 123, 127

- Nekrasov, pp. 49, 54

- Halpern, p. 230

- Halpern, p. 231

- Nekrasov, p. 67

- Nekrasov, p. 116

- Bascomb, p. 185

- Bascomb, pp. 183–184

- Oscherwitz & Higgins, pp. 320–321

- McLaughlin 2003, p. 52

- Bordwell, pp. 43, 267

- Quoted in Taylor, p. 76

- Taylor, p. 76

- Quoted in Taylor, p. 78

- Beshoff, Ivan (28 October 1987). "Last Survivor of Mutiny on the Potemkin". The New York Times. Associated Press.

Sources

- Bascomb, Neal (2007). Red Mutiny: Eleven Fateful Days on the Battleship Potemkin. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-618-59206-7.

- Bordwell, David (1993). The Cinema of Eisenstein. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-13138-X.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Godin, Oleg A. & Palmer, David R. (2008). History of Russian Underwater Acoustics. Singapore: World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-256-825-0.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-352-4.

- McLaughlin, Stephen (2001). "Predreadnoughts vs a Dreadnought: The Action off Cape Sarych, 18 November 1914". In Preston, Antony (ed.). Warship 2001–2002. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 117–140. ISBN 0-85177-901-8.

- McLaughlin, Stephen (2003). Russian & Soviet Battleships. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-481-4.

- Nekrasov, George (1992). North of Gallipoli: The Black Sea Fleet at War 1914–1917. East European Monographs. Vol. CCCXLIII. Boulder, Colorado: East European Monographs. ISBN 0-88033-240-9.

- Oscherwitz, Dayna & Higgins, MaryEllen (2007). Historical Dictionary of French Cinema. Historical Dictionaries of Literature and the Arts. Vol. 15. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7038-3.

- Polmar, Norman & Noot, Jurrien (1991). Submarines of the Russian and Soviet Navies, 1718–1990. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-570-1.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

- Smigielski, Adam (1979). "Imperial Russian Navy Cruiser Varyag". In Roberts, John (ed.). Warship III. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 155–167. ISBN 0-85177-204-8.

- Taylor, Richard (2000). The Battleship Potemkin. KINOfiles Film Companion. Vol. 1. London & New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1-86064-393-0.

- Zebroski, Robert (2003). "The Battleship Potemkin and Its Discontents, 1905". In Bell, Christopher M.; Elleman, Bruce A. (eds.). Naval Mutinies of the Twentieth Century: An International Perspective. London: Frank Cass. pp. 7–25. ISBN 0-203-58450-3.

External links

- Battleship Kniaz Potemkin Tavricheskiy on Black Sea Fleet

- A history of the ship, with photos of a model under construction Archived 6 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- A brief contemporary article by Lenin on the mutiny with the text of the sailors' manifesto

- Christian Rakovsky, The Origins of the Potemkin Mutiny (1907)

- Annotated version of Zecca's La Révolution en Russe