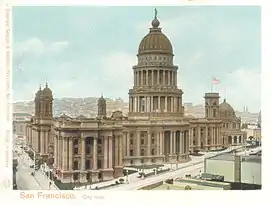

San Francisco City Hall

San Francisco City Hall is the seat of government for the City and County of San Francisco, California. Re-opened in 1915 in its open space area in the city's Civic Center, it is a Beaux-Arts monument to the City Beautiful movement that epitomized the high-minded American Renaissance of the 1880s to 1917. The structure's dome is taller than that of the United States Capitol by 42 feet (13 m).[8] The present building replaced an earlier City Hall that was destroyed during the 1906 earthquake, which was two blocks from the present one.

| San Francisco City Hall | |

|---|---|

(2008) | |

San Francisco City Hall Location within San Francisco | |

| General information | |

| Type | Government offices |

| Architectural style | Beaux-Arts |

| Location | 1 Dr. Carlton B. Goodlett Place San Francisco, California |

| Coordinates | 37°46′45″N 122°25′09″W |

| Construction started | April 5, 1913[1] |

| Completed | July 28, 1916[2] |

| Cost | US$3.4 million ($91.1 million dollars[3] in 2016) |

| Owner | City and County of San Francisco |

| Management | Real Estate Division |

| Height | |

| Antenna spire | 93.73 m (307.5 ft) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 5, including ground floor |

| Floor area | >46,000 m2 (500,000 sq ft) |

| Lifts/elevators | 9 (6 passenger, 3 freight) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Bakewell & Brown |

San Francisco Designated Landmark | |

| Designated | 1970[4] |

| Reference no. | 21 |

| References | |

| [5][6][7] | |

The principal architect was Arthur Brown, Jr., of Bakewell & Brown, whose attention to the finishing details extended to the doorknobs and the typeface to be used in signage. Brown also designed the San Francisco War Memorial Opera House, Veterans Building, Temple Emanuel, Coit Tower and the Federal office building at 50 United Nations Plaza.

Architecture

The building's vast open space is more than 500,000 square feet (46,000 m2) and occupies two full city blocks. It is 390 ft (120 m) between Van Ness Avenue and Polk Street, and 273 ft (83 m) between Grove and McAllister Streets. Its dome, which owes much to Mansart's Baroque domes of the Val-de-Grâce (church) and Les Invalides[9] in Paris, rises 307.5 ft (93.7 m) above the Civic Center Historic District. It is 19 ft (5.8 m) higher than the United States Capitol, and has a diameter of 112 ft (34 m), resting upon 4 x 50 ton (44.5 metric ton) and 4 x 20 ton (17.8 metric ton) girders, each 9 ft (2.7 m) deep and 60 ft (18 m) long.

The building as a whole contains 7,900 tons (7,035 metric tons) of structural steel from the American Bridge Company of Ambridge, Pennsylvania near Pittsburgh. It is faced with Madera County granite on the exterior, and Indiana sandstone within, together with finish marbles from Alabama, Colorado, Vermont, and Italy. Much of the statuary is by Henri Crenier.

The upper levels of the Rotunda are public and handicapped accessible. Opposite the grand staircase, on the second floor, is the office of the Mayor. Bronze busts of former Mayor George Moscone and his successor, Dianne Feinstein, stand nearby as tacit reminders of the Moscone assassination, which took place just a few yards from that spot in the smaller rotunda of the mayor's office entrance. A bust of former county supervisor Harvey Milk, who was assassinated in the building was unveiled on May 22, 2008.[10] While hard to discern these days, the inscription that dominates the grand Rotunda and the entrance to the mayor's small rotunda, right below Father Time, reads:

SAN • FRANCISCO

O • GLORIOVS • CITY • OF • OVR

HEARTS • THAT • HAST • BEEN

TRIED • AND • NOT • FOVND

WANTING • GO • THOV • WITH

LIKE • SPIRIT • TO • MAKE

THE • FVTVRE • THINE

1912 JAMES ROLPH JR. MAYOR 1931[11]

The words were written by the previous Mayor Edward Robeson Taylor, and dedicated by Mayor James Rolph.

While plaques at the Mall entrance memorialize President George Washington's farewell address and President Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address, the primary themes of the statuary are to the past mayors, with the dates of their terms in office. The medallions in the vaults of the Rotunda are of Equality, Liberty, Strength, Learning and, as memorialized in the South Light Court display, Progress.

History

The current City Hall building is a replacement for the original building, which was designed by Augustus Laver and Thomas Stent and completed in 1899 after 27 years of planning and construction.[12] The original city hall was a much larger building which also contained a smaller extension which contained the city's Hall of Records. It was bounded by Larkin Street, McAllister Street, and City Hall Avenue (a street, now built over, which ran from the corner of Grove and Larkin to the corner of McAllister and Leavenworth), largely where the current public library and U.N. Plaza stand today. Noted city planner and architect Daniel Burnham published a plan in 1905 to redesign the city, including a new Civic Center complex around City Hall,[13] but the plans were shelved in the wake of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, which destroyed the 1899 City Hall.

Ever since the fire the ample ruins of the old city hall have been displayed to visitors. There is hardly a citizen that has not been embarrassed at some time or other by pertinent questions about our city hall.

Mayor James "Sunny Jim" Rolph, 1912 San Francisco Call editorial[14]

Reconstruction plans following the earthquake for the Civic Center complex called for a neo-classical design as part of the city beautiful movement, as well as a desire to rebuild the city in time for the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition. A bond was authorized for $8.8 million on March 28, 1912, of which the new City Hall was budgeted for $3.5 million to $4 million.[15] After Arthur Brown Junior's design was selected from the competition, construction started in 1913 and was completed by 1915, in time for the Exposition.[12]

.jpg.webp)

Ground was broken for the new City Hall at Van Ness and Fulton on April 5, 1913,[1][16] and the cornerstone was laid on October 25 of that year.[15][17] Mayor Rolph moved into City Hall on December 28, 1915,[18] the final stone was laid on March 31, 1916,[19] and scaffolding was finally removed on July 28, officially marking the end of construction.[2] The ruins of the old City Hall were sold shortly thereafter in August 1916 for US$2,300 (equivalent to $57,000 in 2021), with removal to be completed within 40 days.[20]

The main rotunda served as the site where many prominent politicians and public servants laid in state. General Fredrick Funston, hero of the Spanish–American War, Philippine–American War, and the 1906 earthquake laid there in 1917.[21] Former mayor and governor James Rolph laid in state in City Hall following his death in 1934.[22]

Joe DiMaggio and Marilyn Monroe were married at City Hall in January 1954.[23]

In May 1960, the main Rotunda was a site of a student protest against the House Un-American Activities Committee and a countering police action whereby students from UC Berkeley, Stanford, and other local colleges were fire hosed down the steps beneath the rotunda. This event was memorialized by students during the Free Speech Movement at UC Berkeley four years later.

Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk were assassinated at City Hall in 1978, by former Supervisor Dan White.

The Loma Prieta earthquake of 1989 damaged the structure, and twisted the dome four inches (102 mm) on its base. Afterward, under the leadership of the San Francisco Bureau of Architecture in collaboration with Carey & Co. preservation architects, and Forell/Elsesser Engineers, work was completed to render the building earthquake resistant through a base isolation system,[notes 1] which would likely prevent total collapse of the building. City Hall reopened after its seismic upgrade in January 1999, and was the world's largest base-isolated structure at that time.[24]

Prior to the retrofitting, the San Francisco County Superior Court’s civil courtrooms were located in City Hall, but have been located across the street at the 400 McAllister courthouse since it opened in 1997.[25]

The original grand plaza has undergone several extensive renovations, with radical changes in its appearance and utility. Prior to the 1960s there were extensive brick plazas, few trees, and a few large, simple, raised, and circular ponds with central fountains, all in a style that discouraged loitering. The plaza was then extensively excavated for underground parking. At this time a central rectangular pond, with an extensive array of water vents (strangely, all in several strict rows and all pointing east, with identical arcs of water, and completely without sculptural embellishment), was added, with extensive groves of trees (again, in 60s modernist style, planted with absolute military precision on rectangular grids). In the 1990s, with the rise of the problem of homelessness, the plaza was once again remodeled to make it somewhat less habitable—although the most significant change, the replacement of the pond and pumps with a lawn, could be reasonably justified on the basis of energy and water conservation.

The building features color changeable LED lighting at the outside of the Rotunda, and between the exterior columns. The colors change to coincide with different events happening in the city and elsewhere.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, City Hall was closed from March 2020 until reopening on June 7, 2021.[26]

In popular culture

- Dirty Harry (1971) filmed several scenes at City Hall, including inside the Mayor's office.[27]

- The Towering Inferno (1974)[27]

- Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978)[27]

- Foul Play (1978)[27]

- A View to a Kill (1985)[28]

- The Grand Staircase is featured in the Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) as a stand-in for an unnamed government building in Washington, D.C.[29]

- A View to a Kill (1985)[30]

- Ten-thousand-watt spotlights triggered the fire sprinkler system during the filming of Bicentennial Man (1999), resulting in water damage. The crew previously shot in the Supervisors' chambers.[31]

- Milk (2008)[27][32]

See also

- List of San Francisco Designated Landmarks

- List of tallest buildings in San Francisco

- List of tallest domes

References

Informational notes

- In an earthquake, the mass of the dome threatens to act as a pendulum, rocking the building's structure and tearing it apart, but the base isolation system of hundreds of rubber and stainless-steel insulators inserted into City Hall's underpinnings should have the effect of disrupting seismic waves before they can affect the structure.

Citations

- "City Hall Excavating Officially Begins". San Francisco Call. 6 April 1913. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- "City Hall Finished". Press Democrat. 29 July 1916. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- "City of San Francisco Designated Landmarks". City of San Francisco. Retrieved 2012-10-21.

- "Emporis building ID 118739". Emporis. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016.

- "San Francisco City Hall". SkyscraperPage.

- San Francisco City Hall at Structurae

- Gosciniak, Gregor (26 June 2005). "San Francisco City Hall". CityMayors. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- Rough Guides; Edwards, Nick; Hodgkins, Charles; & Keeling, Stephen (2014) The Rough Guide to California Rough Guides Limited. ISBN 9780241007648

- Daub Firmin Hendrickson Sculpture Group (2007). "Winning Maquette for Harvey Milk City Hall Memorial Sculpture Competition". The Harvey Milk City Hall Memorial Committee. Archived from the original on 2008-12-03. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- "MermaidVision - P3090056". Archived from the original on 2004-09-07.

- "San Francisco Attractions: City Hall". A View on Cities. 2009. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- Burnham, Daniel H.; Bennett, Edward H. (September 1905). O'Day, Edward F. (ed.). Report on a plan for San Francisco (Report). Association for the Improvement and Adornment of San Francisco. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- "The Need for a New City Hall and People's Center". San Francisco Call. 24 March 1912. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- "Godspeed to the New City Hall, Started Today". San Francisco Call. 25 October 1913. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- "Now for New City Hall". San Francisco Call. 5 April 1913. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- "Rolph Lays City Hall's Stone". San Francisco Call. October 25, 1913. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- "War Necessities Drive Men to Substitutes In Manufactures". Morning Press. A.P. 29 December 1915. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- "Last Stone Laid In S.F. City Hall". Madera Tribune. 1 April 1916. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- "Bay City Hall Ruins Sold". Sacramento Union. 9 August 1916. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- "Funston's Body Lies In State at Bay". Sacramento Union. 24 February 1917. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- "State Mourns at Rolph's Bier". Healdsburg Tribune. 4 June 1934. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- "Gorgeous Marilyn Monroe Married to Joe DiMaggio". San Bernardino Sun. AP. 15 January 1954. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- Adams, Gerald (29 December 1998). "Rebuilt, restored reborn: City Hall reopens, with jewels polished and population reduced". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- "San Francisco County / Historic California County Courthouses | CSCHS". California Supreme Court Historical Society. Retrieved 2021-12-02.

- RODRIGUEZ, OLGA R. (2021-06-07). "San Francisco's City Hall hosts 4 weddings in reopening". SFGATE. Retrieved 2021-06-08.

- Hartlaub, Peter (November 22, 2010). "Six best uses of San Francisco City Hall in the movies". The Poop. San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on June 18, 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- Wilson, Sean (September 21, 2021). "James Bond movies revisited: A View To A Kill | Cineworld cinemas". Cineworld. Retrieved 2022-10-20.

- Harris, Scott Jordan, ed. (2013). World Film Locations: San Francisco. Chicago, Illinois: Intellect Books, The University of Chicago Press. pp. 82–83. ISBN 978-1-78320-028-3. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- "Photo: Grace Jones and Tanya Roberts at City Hall in San Francisco to introduce latest James Bond film "A View to a Kill" - ARKMILT19850505003". UPI. Retrieved 2022-10-20.

- "City Hall Doesn't Want to See Sequel to Disney Movie Flood / Stricter regulations on events held there being considered". 19 June 1999.

- Kit, Borys (February 1, 2008). "'Milk' shoot does the Castro good". The Hollywood Reporter.

External links

- San Francisco City Hall – official site

- Virtual Tour of City Hall and Dome An unofficial guide to items of historic, artistic and architectural interest.

- 360 degree panoramic photographs of San Francisco's City Hall, from Don Bain's 360° Panoramas

- San Francisco government City hall restoration project (late 1990s)

- Historic American Buildings Survey (Library of Congress): City Hall, Civic Center, San Francisco, San Francisco County, CA

- Images of City Hall and Civic Center, 1912-1918 and The New City Hall, 1915, The Bancroft Library

.svg.png.webp)