Sandakan

Sandakan (Malaysian pronunciation: [ˈsaan daˈkan], Jawi: سنداکن, Chinese: 山打根; pinyin: Shāndǎgēn; Jyutping: saan1 daa2 gan1) formerly known at various times as Elopura, is the capital of the Sandakan District in Sabah, Malaysia. It is the second largest city in Sabah after Kota Kinabalu. It is located on the Sandakan Peninsula and east coast of the state in the administrative centre of Sandakan Division and was the former capital of British North Borneo. In 2010, the city had an estimated population of 157,330[2] while the surrounding municipal area had a total population of 396,290.[2] The population of the municipal area had increased to 510,600 by 2020.[3]

Sandakan

Elopura | |

|---|---|

District capital | |

| Other transcription(s) | |

| • Jawi | سنداکن |

| • Chinese | 山打根 |

From top, left to right: Sandakan City, the Sandakan Municipal Council, the State Secretariat Building, Sandakan Sports Complex, the Sandakan Regional Library, the Sandakan District Mosque, the St. Michael's and All Angels Church, the Tam Kung Temple, and View of Sandakan Bay | |

Seal | |

| Nickname(s): The Nature City, Little Hong Kong | |

Location of Sandakan in Sabah | |

| Coordinates: 05°50′0″N 118°07′0″E | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Division | Sandakan |

| Bruneian Empire | 15th century–1704 |

| Sultanate of Sulu | 1704–1882 |

| Settled by BNBC | 21 June 1879 |

| Declared capital of North Borneo | 1884 |

| Discontinuation as capital | 1946 |

| Municipality | 1 January 1982 |

| City | TBA |

| District | Sandakan |

| Government | |

| • Council President | Benedict Asmat |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2,266 km2 (875 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 10 m (30 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 510,600 |

| • Density | 230/km2 (580/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (MST) |

| • Summer (DST) | Not observed |

| Postal code | 90000 to 90999 |

| Area code(s) | 089 |

| Vehicle registration | ES (1967-1980), SS(1980-2018), SM (2018-Present) |

| Website | mps |

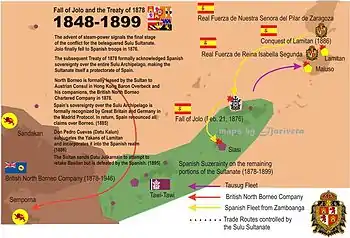

Before the founding of Sandakan, Sulu Archipelago was the source of dispute between Spain and the Sultanate of Sulu for economic dominance in the region. By 1864, Spain had blockaded the Sultanate possessions in the Sulu Archipelago. The Sultanate of Sulu awarded a German consular service ex-member a piece of land in the Sandakan Bay to seek protection from Germany. In 1878, the Sultanate sold north-eastern Borneo to an Austro-Hungarian consul who later left the territory to a British colonial merchant. The German presence over the area raised concern among the British. As a result, a protocol was signed between the British, German and the Spanish to recognise Spanish sovereignty over the Sulu Archipelago, in return for the Spanish not intervening in British affairs in northern Borneo.

Sandakan began to prosper when the British North Borneo Company (BNBC) started to build a new settlement in 1879, developing it into an active commercial and trading centre as well as making it the main administrative centre for North Borneo. The British also encouraged the migration of the Chinese from British Hong Kong to develop the economy of Sandakan. However, the prosperity halted when the Japanese occupied the area. As the war continued and Allied bombing started in 1944, the town was totally destroyed. Unable to fund the costs of the reconstruction, the administrative powers of North Borneo were handed over to the Crown Colony government. Subsequently, the administrative capital of North Borneo was moved to Jesselton. As part of the 1948–1955 Colonial Office Reconstruction and Development Plan, the crown colony government began to develop the fishing industry in Sandakan.

Sandakan is one of the main ports for oil, tobacco, coffee, sago, and timber exports. Other economic activities include fishing, ship building, eco-tourism, and manufacturing. Among the tourist attractions in Sandakan are Sandakan Heritage Museum, Sandakan Cultural Festival, Sandakan War Memorial, Sepilok Orang Utan Sanctuary, Turtle Islands National Park, and Gomantong Caves.

Etymology

.jpg.webp)

A first European settlement was built by a Scottish arms smuggler from Glasgow named William Clark Cowie who named the settlement "Sandakan", (which in the Suluk language means "The place that was pawned").[4] It was soon renamed Kampong German (Kampung Jerman), due to the presence of several German bases there. When another new settlement was built shortly after the previous Cowie settlement had been destroyed by a fire, it was called as Elopura, meaning "beautiful town".[5] The name was given by the British North Borneo Company but the locals persisted to use the old name and later it was changed back to Sandakan.[5][6][7] Besides Elopura, it was also nicknamed Little Hong Kong due to a strong presence of ethnic Chinese migration from Hong Kong (mainly Cantonese and Hakka).[8][9][10] It was Pryer who gave the settlement the name Elopura meaning "beautiful town". Several years later the settlement was again renamed Sandakan.[11] The name Elopura, however, is still used for some local government functions of the Sabah State Legislative Assembly, including elections.[12] The town is usually referred as "Sandakan" nowadays instead of "Elopura" or "Little Hong Kong". However, efforts have been made to develop Sandakan so that the town is fitting to have the name of "Little Hong Kong" again.[13][14]

History

Like most of Borneo, this area was once under the control of the Bruneian Empire[15] in the 15th century before being ceded to the Sultanate of Sulu between the 17th[16] and 18th centuries[17] as a gift for helping the Bruneian forces during the Brunei Civil War. Since the 18th century, Sandakan start to be ruled by the Sultanate of Sulu.[18] In 1855, when Spanish power began to expand in the Philippine archipelago, they began to restrict the trade of foreign nations with Sulu by establishing a port in Zamboanga and issuing a ruling which declared that ships wanting to engage in trade with the Sulu Archipelago must first visit the Spanish port.[19] In 1860, the Sultanate of Sulu became important to the British as their archipelago could allow the British to dominate trade routes from Singapore to Mainland China. But in 1864, William Frederick Schuck, a German ex-member for the German consular service arrived in Sulu and met Sultan Jamal ul-Azam, who encouraged him to remain in Jolo.[19] Schuck associated himself with the Singapore-German trading firm of Schomburg and began working in the interest of the Sultan and Datu Majenji, who was an overlord in the island of Tawi-Tawi. While he continued his voyage to Celebes, he decided to open his first headquarters at Jolo. Large quantities of arms, opium, textiles and tobacco from Singapore were shipped to Tawi-Tawi in exchange for slaves from the Sultanate.[19]

In November 1871, Spanish gunboats bombarded Samal villages in Tawi-Tawi islands and blockaded Jolo. As war in the waters of Sulu began to escalate, the Sultanate came to rely on Singapore's market for assistance.[19] When the Sultanate increased their close trade relations with the British trading ports of Labuan and Singapore, this forced the Spanish to take another major step to conquer the Sulu Archipelago. The arrival of German warship Nymph at the Sulu Sea in 1872 to investigate the Sulu-Spanish conflict made the Sultanate believe Schuck was connected with the German government,[20] thus the Sultanate granted Schuck an area of land in the Sandakan Bay to establish a trading port to monopolise the rattan trade in the northeast coast where Schuck could operate freely without the Spanish blockade.[19] The intervention of Germans on the Sulu issue caught the British' attention and made them suspicious, especially when the Sultanate had asked for protection from them.[20] Schuck then established warehouses and residences in the Sandakan Bay, along with the arrival of two steamers under the German flag and it served as a base for the running of gunpowder and firearms. When another German warship Hertha visited Sandakan Bay, its commander described the activity in Kampung Jerman:[19]

... during our stay, two small steamers under German flag, ostensibly coming from Labuan, ran in; also third, of about the same size, with a flag of all yellow, the property and flag, as I was told of the Datu Alum. Judging from the stores in the settlement, cotton goods, arms and especially firearms, appears to be the articles of trade with the natives of Sulu.[19]

In 1878, the Sultanate of Sulu sold their land in north-eastern Borneo to an Austro-Hungarian consul named Baron von Overbeck.[19] After efforts by Overbeck to sell northern Borneo to the German Empire, Austria-Hungary and the Kingdom of Italy for use as a penal colony were unsuccessful, he withdrew in 1879. This left Alfred Dent to manage and establish the North Borneo Provisional Association Ltd, as Sandakan became the capital of North Borneo in 1884.

As the capital of North Borneo, Sandakan become an active commercial and trading centre. The main trading partners were Hong Kong and Singapore. Many Hong Kong traders eventually settled in Sandakan and in time the town was called the 'Little Hong Kong of North Borneo'.[21] The Cowie settlement was accidentally burnt down on 15 June 1879 and was never thereafter rebuilt.[22] The first British Resident, William B. Pryer then moved the administration to a new settlement on 21 June 1879 to a residence in what is today known as Buli Sim Sim near Sandakan Bay.

.JPG.webp)

During Pryer's tenure of being the first resident of Sandakan, one of his first tasks was to establish law and order. The situation in the nascent colony remained tense, with the Borneans being hostile towards the authority of the British North Borneo Company, and all-out warfare prevented only by the presence of Royal Navy ships offshore. To resolve the situation, Pryer imported policemen from British India and Singapore. His first contingent of police was made up of Indian Sikhs with a large body stature.[23] The Indian police were probably from the Sepoy Company in India and were generally called 'Sipai' by the locals.[21]

Meanwhile, the Spanish continued to strengthen their blockade of trade activities in the Sulu Archipelago, resulting in the blockade's opposition by Germans when many of their trading ships were seized by Spain. Both the German and British governments stated the archipelago should remain open to world trade route.[19] Soon, the British began to co-operate with the Germans when rumours about the seizure of their trading ship by the Spanish began arriving to Great Britain which lead the British to oppose the Spanish action.[20] British and Germans then refused to recognise the Spanish sovereignty over Sulu. But with strong opposition from Germans over the illegal seizures of their ships and the British fear of the German presence (which was stronger than the Spanish during the time),[20] a protocol known as Madrid Protocol was then signed in Madrid to secure Spanish sovereignty over the archipelago, making the Spanish free to wage any war with the Sultanate of Sulu without the fear of other foreign western powers intervening and as a return the Spanish would not intervene in the affairs of British in northern Borneo.[19][20]

The prosperity of Sandakan as the capital of North Borneo was however ended when the Japanese occupied the town on 19 January 1942.[4][24] During their occupation, the Japanese restored the town's previous name, Elopura and established a prisoner of war camp to hold their captive enemies. Allied planes started to raid Sandakan in September 1944. As the Japanese feared further retaliation from the Allied forces, they began to move all prisoners and forced them to march to Ranau.[25] Thousands of British and Australian soldiers lost their lives during this forced march in addition to Javanese labourers from the Dutch East Indies.[26][27][28] Only six Australian soldiers survived from this camp, all after escaping. Sandakan was completely destroyed both by bombing from Allied forces and by the Japanese occupation.[6][29][30]

.JPG.webp)

At the end of the war, the British North Borneo Company returned to administer the town but were unable to finance the costs of reconstruction. They gave control of North Borneo to the British Crown on 15 July 1946. The new colonial government chose to move the capital of North Borneo to Jesselton instead of rebuilding it as the cost of reconstruction was higher due to the damage. Although Sandakan was no longer the administrative capital, it still remained as the "economic capital" with its port activities related to the export of timber and other agricultural products in the east coast.[31] To improve the facilities, the Crown Colony administration designed a plan, later known as the "Colonial Office Reconstruction and Development Plan for North Borneo: 1948–1955”. This plan established the Sandakan Fisheries Department in April 1948. As a first step towards the development of Sandakan's fishing industry, the Crown Colony devised the "Young Working Plan" through the "Colonial Development and Welfare Scheme". Through this plan, the British administration were given the responsibility to import basic materials from Hong Kong for fishermen and distribute the materials at a price lower than the one offered by the capitalists. As a result, Hong Kong towkays (bosses) were involved with the fishing industry in Sandakan.[31]

Government and international relations

The town has twin town arrangements with Burwood, Australia[32] and Zamboanga, Philippines.[33]

There are three members of parliament (MPs) representing the three parliamentary constituencies in the district: Libaran (P.184), Batu Sapi (P.185), and Sandakan (P.186).

The town is administered by the Sandakan Municipal Council (Majlis Perbandaran Sandakan). The current President of Sandakan Municipal Council is Benedict Asmat, who took over from Wong Foo Tin in December 2021. The area under the jurisdiction of the Sandakan District covers the town area (46 square miles), half-town area (56 square miles), rural areas and islands (773 square miles) with all the total area are 875 square miles.[34]

Security

Sandakan is one of the six districts that is involved in the Eastern Sabah Security Command (ESSCOM), a dusk to dawn sea curfew which had been enforced since 19 July 2014 by the Malaysian government to repel attacks from militant groups in the Southern Philippines.[35]

Geography

Sandakan is located on the eastern coast of Sabah facing the Sulu Sea, with the town is known as one of the port towns in Malaysia.[36] The town is located approximately 1,900 kilometres from the Malaysia's capital Kuala Lumpur, 28 kilometres from the international border with the Philippines and 319 kilometres from Kota Kinabalu, the capital of Sabah.[34][37] The district itself is surrounded by Beluran (known as Labuk-Sugut District before) and Kinabatangan district.[38][39] Not far from the town, there are the three Malaysian Turtle Islands, Selingaan, Gulisaan and Bakkungan Kechil.[40] The nearest islands to the town are Berhala, Duyong, Nunuyan Darat, Nunuyan Laut, and Bai island.[38]

Climate

Sandakan has a tropical rainforest climate under the Köppen climate classification. The climate is relatively hot and wet with average shade temperature about 32 °C, with around 32 °C at noon falling to around 27 °C at night. The town sees precipitation throughout the year, with a tendency for October to February to be the wettest months, while April is the driest month. Its mean rainfall varies from 2184 mm to 3988 mm.[41][42]

| Climate data for Sandakan (1961–1990, extremes 1879–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 34.8 (94.6) |

34.1 (93.4) |

33.6 (92.5) |

36.1 (97.0) |

36.5 (97.7) |

35.9 (96.6) |

35.9 (96.6) |

36.0 (96.8) |

35.6 (96.1) |

35.3 (95.5) |

34.6 (94.3) |

34.2 (93.6) |

36.5 (97.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 29.2 (84.6) |

29.5 (85.1) |

30.5 (86.9) |

31.6 (88.9) |

32.5 (90.5) |

32.2 (90.0) |

32.2 (90.0) |

32.3 (90.1) |

31.5 (88.7) |

31.6 (88.9) |

30.7 (87.3) |

29.8 (85.6) |

31.1 (88.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 26.2 (79.2) |

26.4 (79.5) |

27.0 (80.6) |

27.6 (81.7) |

27.7 (81.9) |

27.3 (81.1) |

27.1 (80.8) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.0 (80.6) |

26.9 (80.4) |

26.8 (80.2) |

26.5 (79.7) |

27.0 (80.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 23.3 (73.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.5 (74.3) |

23.7 (74.7) |

23.7 (74.7) |

23.4 (74.1) |

22.1 (71.8) |

23.1 (73.6) |

22.6 (72.7) |

23.2 (73.8) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.4 (74.1) |

23.2 (73.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 18.3 (64.9) |

19.4 (66.9) |

20.0 (68.0) |

21.1 (70.0) |

21.1 (70.0) |

20.6 (69.1) |

20.2 (68.4) |

19.4 (66.9) |

20.6 (69.1) |

20.6 (69.1) |

20.0 (68.0) |

20.1 (68.2) |

18.3 (64.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 436.8 (17.20) |

267.6 (10.54) |

157.8 (6.21) |

107.3 (4.22) |

137.6 (5.42) |

200.3 (7.89) |

194.7 (7.67) |

212.6 (8.37) |

236.9 (9.33) |

252.5 (9.94) |

344.2 (13.55) |

461.8 (18.18) |

3,010.1 (118.51) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 18 | 12 | 10 | 7 | 9 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 15 | 18 | 19 | 158 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 84 | 83 | 82 | 81 | 82 | 82 | 83 | 83 | 84 | 85 | 86 | 86 | 84 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 155.6 | 160.9 | 217.5 | 247.0 | 248.9 | 206.9 | 220.9 | 221.5 | 194.9 | 190.7 | 174.5 | 159.9 | 2,399.2 |

| Source 1: NOAA[43] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Meteo Climat (record highs and lows),[44] Deutscher Wetterdienst (humidity, 1966–1990)[45] | |||||||||||||

Demography

Ethnicity and religion

According to the Malaysian Census in 2010, the whole town municipality's area has a total population of 396,290.[2] Non-Malaysian citizens form the majority of the town population with 144,840 people followed by other Bumiputras (100,245), Chinese (63,201), Bajau/Suluk (38,897), Malay (Bruneian Malays as well as Kedayans who are migrants from the West Coast and their descendants together with ethnic Cocos Malay internal migrants from the Tawau division, as well as ethnic Malays native to the town originating from these ethnic groups such as the Bugis, Javanese and Banjarese peoples) (22,244), Kadazan-Dusun (16,616), Indian (974), Murut (519) and others (8,754).[2]

Most of the non-Malaysian citizens are from the southern Philippines.[13][46] The Chinese population here are equal proportions of mostly Cantonese (descendants of seafaring traders who settled in the East Coast of North Borneo then) and also Hakka (mostly descended from voluntary migrants and Taiping Rebellion refugees), who arrived during the British period and had their original settlements before in the town which is now known as the Chinese Farm River Village.[9] The Bajau, Suluk and Malays are majority Muslims, Kadazan-Dusuns and Muruts mainly practice Christianity with some of them having become Muslims[47] while the Chinese are mainly Buddhists, Taoist and some Christians.[48][49] There is also a small number of Hindus, Sikhs, Animists, and secularists.

The large group of non-citizens have been identified as a majority Muslim, and there are some Christian Filipino women who converted to Islam to marry Muslim Filipinos here.[46] Like in Kota Kinabalu, the first wave of these immigrants arrived in the late 15th century during the Spanish colonisation, while the others arrived in the early 1970s because of the troubles in southern Philippines.[46] They consist of migrant workers, with many of them being naturalised as Malaysian citizens. However, there are still many who live without proper documentation as illegal immigrants in the town with their own illegal settlement.[46]

Languages

Like the national language, the people of Sandakan mainly speak Malay, with a distinct Sabahan creole.[50] The Malay language in Sandakan are different from the Malay language in the west coast which resembles Brunei Malay.[51] In Sandakan, this language has been influenced by many words from the Suluk language.[52] As Sandakan had also been dominated by the Hakka and Cantonese Chinese, Hakka and Cantonese widely spoken, while today Mandarin, as well as a lesser extent Cantonese dominates as the lingua franca among both dialect subgroups (since both the local ethnic Chinese populations native to this town shares the same ancestral province in China, Guangdong, in the case of the usage of the Cantonese dialect as a lingua franca amongst both the local Cantonese and Hakka populations, while Mandarin is the standardized spoken form of the Chinese language used in the business and education sectors). While for the east coast Bajau, their language has similarities with the Sama language in the Philippines and also borrowed many words from the Suluk language which is different from the west coast Bajau who had been influenced by the Malayic languages of Brunei Malay.[53][54]

Economy

During the British period, Sandakan grew quickly as one of the largest British settlements on the east coast of North Borneo including having been the former capital of the territory.[55] It grew rapidly due to the export activities as a port town. The port is important for palm oil, tobacco, cocoa, coffee, manila hemp and sago exports.[5][56] In the mid-1930s, the export of tropical timber from Sandakan recorded a level of 180,000 cubic metres which made the town as the world's largest exporter of hardwood.[5] Many Sandakan wood logs are now found in Beijing's Temple of Heaven.[55] Sandakan also enjoyed modern developments such as telegraph service to London and paved streets before Hong Kong and Singapore.[55]

The overseas Chinese have contributed to the development of the town since their immigration in the late 19th century.[57] The immigrants to Sandakan were farmers and labourers while some of them worked as businessmen and entrepreneurs.[9][57] In the modern days, Sandakan have been poised to become one of Sabah business hubs.[58] The town itself is one of Sabah's major port, other than in Kota Kinabalu, Sepanggar Bay, Tawau, Lahad Datu, Kudat, Semporna and Kunak.[36][59] Sandakan district is known for its eco-tourism centres, such as the orangutan rehabilitation station in Sepilok Rehabilitation Centre, the Turtle Islands Park, the Kinabatangan River and the Gomantong Caves which are famous for their edible bird's nest.[58] Due to Sandakan geographical proximity to Southern Philippines, there is also a barter trade connection and Sandakan is considered as a transit point for food entering the Southern Philippines. The state government has been assisting traders to improve their trading system and providing infrastructure facilities.[60]

Sandakan main industrial zones are basically based on three areas such as the Kamunting area known for its oil depots, edible oil refinery and glue factories.[61] In Batu Sapi, a shipyard, fertiliser oxygen gas and wood-based factories are situated.[61] Since 2012, the State Public Works Department (PWD) has undertaking three projects to upgrade roads in Sandakan.[62] A grand specialised industrial park, Majulah Industrial Centre have also started operating in 2015.[63][64] The proposed Seguntor industrial area consists of 1,950 hectares (4,833 acres) is originally an agricultural area and the area is now in the process to be re-zoning into an industrial area. 2,531 acres will be for wood-based industries while another 2,302 will be used for general industries. At present, 55 wood-based factories have been approved, of which 35 has been into operation. While another total of 340 hectares area for general industries and 30 hectares for service industries are located in various parts of Sandakan.[61]

But in recent years, many businessmen have shifted their operations away from the town centre to other suburbs due to a large presence of illegal immigrants from Mindanao islands in the Philippines which has caused trouble, mostly crime such as theft and vandalism on public facility and also solid waste pollution in marine and coastal areas.[46][56][65] But later in January 2003, an urban renewal project, was launched to revive the town centre as a commercial hub in Sandakan and since 2013, the Government of Malaysia has launched a major crackdown on illegal immigrants.[56][66]

Transportation

All the internal roads linking different parts of the town are generally state roads constructed and maintained by the state's Public Works Department, while the local council (Sandakan Municipal Council) oversees the housing estates roads.[67] Currently, most roads in Sandakan are undergoing major upgrades due to issues like the lack of road networks and overloading.[67][68] There is only one federal arterial road which links Sandakan to the west coast of Sabah, the Federal Route 22, while other roads including the internal roads are called state roads.[67] Most major internal roads are dual-carriageways. The only highway route from Tawau connects: Sandakan – Telupid – Ranau – Kundasang – Tamparuli – Tuaran – Kota Kinabalu, as well Lahad Datu – Kunak – Semporna – Tawau (part of the Pan Borneo Highway)[69]

Regular bus services with minivans and taxis also can be found.[70][71] There are three bus terminals operating in the town such as the Buses to Sepilok, Local Bus Terminal and the Long Distance Bus Terminal.[72] The long-distance bus terminal is located about 4 km north of the town while the local bus connects with the centre of the town.[70]

Sandakan Airport (SA) (ICAO Code : WBKS) provides flights linking the town to other domestic destinations. To boost the twin town relationship with Zamboanga City and for the ASEAN spirit in the BIMP-EAGA region, there is an international route from Sandakan to Zamboanga International Airport.[73][74] Local destinations for the airport including Kota Kinabalu, Kuching, Kuala Lumpur and many others. It is also one of the destinations for MASWings, which serves flights to other smaller towns or rural areas in East Malaysia. As of 2014, the airport is being upgraded and expanded to accommodate additional travellers.[75]

There is a ferry terminal which connects the town with some parts in the Southern Philippines such as Zamboanga City, the Sulu Archipelago and Tawi-Tawi.[76] The state government have tried to proposed a new ferry terminal in the town to attract more tourist particularly from the Philippines and also from Indonesia.[77] But the proposal was turned down due to the trouble in the southern Philippines which could spread to the state and there is a call from the former Chief Minister of Sabah and the Current President of Sabah Progressive Party Yong Teck Lee to suspend the ferry service to counter the high level of people migration from the Philippines which now has become the major problem to Sabah as they are overstaying in the state and becoming an illegal immigrants.[78][79][80]

Public services

The court complex before this was located near the Lebuh Empat.It started operating since 1957. The court was temporarily relocated to the Wisma Warisan during the renovation work in 1990. The renovation was completed in 1998. Even though the court has been renovated, it still had the same problem just like before where the court still didn't get enough space. They choose too keep the magistrates courts and session courts too continued operating at the Wisma Warisan. The Sandakan War Monument is located in front of the old court today.

In 2001, a new court complex was built in mile 7. The new court complex was completed and started operating in 2003. It was then being launch in 2005.[81] After the new court complex started operating, the old court was then being left completely abandoned. Another court for the Sharia law was also located in the town.[82]

The district police headquarters is located at Lebuh Empat,[83] along with the town police station located not far from the court beside the Wisma Sandakan.[84] Other police station can be found throughout the district such as in KM52, Ulu Dusun and in Seguntor.[85] Police substations (Pondok Polis) are found in Sg. Manila, Suan Lamba, Sibuga and Kim Fong BT4 areas,[85] and the Sandakan Prison is located in the town centre.[86]

There are one public hospital, eight public health clinics, one child and mother health clinic, eight village clinics, three mobile clinics and two 1Malaysia clinics in Sandakan.[87][88] The Duchess of Kent Hospital, which is located along North Street (Jalan Utara), is the main and second largest public hospital in Sabah after the Queen Elizabeth Hospital with 400 beds.[89] Built in 1951, it is also become the first modern and one of the important hospital in Sabah.[89]

In 2008, a private hospital was proposed to be built at the North Street. The Fook Kuin Medical Centre would be the largest private hospital in Sabah with 276 beds surpassing the Sabah Medical Centre with 134 beds in Kota Kinabalu once it finished in 2011.[90][91] The Sandakan Regional Library is located in the town and is one of three regional libraries in Sabah, the other in Keningau and Tawau. All these libraries are operated by the Sabah State Library department.[92]

Education

There are many government or state schools in and around the town. The first primary school in the town was St. Mary Town Primary School which was opened by Rev. Fr. A. Prenger who became the first headmaster along with Rev. Fr. Pundleider, who is a Mill Hill's priests.[4] It is an all boys Catholic Mission School and have been opened since 24 July 1883, making it as the oldest school in Borneo.[93] For the secondary schools, there are Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Elopura, Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Elopura II, Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Batu Sapi, Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Datu Pengiran Galpam, Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Gum-Gum, Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Muhibbah, Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Taman Fajar, Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Perempuan, Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Paris, Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Merpati, Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Segaliud, Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Libaran, Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Sandakan, Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Sandakan II, Sekolah Menengah Tiong Hua, Sekolah Menengah Cecilia Convent, Sekolah Menengah St. Mary, Sekolah Menengah St. Michael, Sekolah Menengah Sung Siew, Sekolah Menengah Teknik Sandakan and Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Agama Sandakan.[94] One independent private school is also present in the town called the Yu Yuan Secondary School.[95]

For higher/tertiary education, there are Sandakan Polytechnic, ILP Sandakan, GIATMARA Sandakan and Kinabalu Commercial College. Universities such as the University of Malaysia Sabah, Open University Malaysia and Universiti Putra Malaysia have a campus here.

Culture and leisure

Several cultural venues are located in Sandakan. The Sandakan Heritage Museum, situated at the Lebuh Empat Road, is the main museum of Sandakan. The museum is located on the right-hand side of the ground and on the first floor of the Wisma Warisan Building which is next to the municipal building.[96] Besides that, a cultural festival known as Sandakan Festival is celebrated once a year in the town, after having been introduced in 2000 by the Sandakan Municipal Council.[97][98]

Another museum in Sandakan is the Agnes Keith House which is located on top of the hill along Istana Street. The house is known as the former home to Harry Keith and his wife Agnes Newton Keith.[99] Other historical attractions include the Chartered Company Memorial, Chong Tain Vun Memorial, Japanese Bunker, Malaysia Fountain, Marian Hill, Mill Hill Dam,[100] North Borneo Scout Movement Memorial, Sandakan Japanese Cemetery, Sandakan Liberation Monument, Sandakan Massacre Memorial, Sandakan Memorial Park, Sandakan War Memorial and the William Pryer Memorial. The oldest religious buildings are the St. Mary's Cathedral, Parish of St. Michael's and All Angels, the Sam Sing Kung Temple and the Jamek Mosque, which was opened by a Muslim cloth merchant from India, known as Damsah, in 1890.[101][102]

A number of leisure spots and conservation areas are available around Sandakan. The Sepilok Orang Utan Sanctuary is a place where orphaned or injured orangutans are brought to be rehabilitated to return to forest life. Established in 1964, it is one of only four orangutan sanctuaries in the world.[103][104] Other conservation areas are the Malaysian Turtle Islands where many turtles lay their eggs on the islands. They cover an area of 1,740 hectares which includes the surrounding reefs and seas. The islands are also ideal for swimming, snorkelling and scuba diving.[105]

Another attraction is the Gomantong Caves, which is home to hundreds of thousands of swifts who build their nests high on cave walls and roofs. Other than swifts, the caves are also inhabited by millions of bats.[103] Furthermore, the Sandakan Orchid House has a collection of rare orchids. Along the Labuk Road from Sandakan, there is a crocodile farm which houses about 1,000 crocodiles of various sizes.[106]

The main shopping area in Sandakan is the Harbour Mall. Launched in 2003, it is located in Sandakan's new central business district and built on a bay of reclaimed land.[104] It is part of the Sandakan Harbour Square and considered as the first modern shopping mall in the town.[107][108] In 2014, a new mall project with 341 units of store has been launched and will become the second main shopping destination for Sandakan once it gets finished.[109][110]

Rugby is very popular in Sandakan. Eddie Butler, a former Welsh Rugby Union captain described it as the "Limerick of the tropics".[111] In 2008, the Borneo Eagles-Sabahans (a team which included a few professional Fijians) at the newly built Sandakan Rugby Club hosted a 10-a-side tournament for the eighth and last time. In 2009, the tournament was changed to seven-a-side.[111]

Other than rugby, a sports complex containing a badminton court, swimming pool, weightlifting room, hockey stadium, football stadium, cricket field, boxing facility and field archery is available in the town.

Notable residents

- Political

- Juhar Mahiruddin: Current Yang di-Pertua Negeri of Sabah[112]

- Liew Vui Keong: Malaysian politician, former parliament member (only represented and lived in the constituency during his tenure of service, born and bred in the western district of Kota Belud and currently living in the capital city, Kota Kinabalu),[113] former minister in the prime minister's department

- Wong Tien Fatt: Former minister of people's health and wellbeing sabah, former member of parliament for sandakan, former deputy chairman of sabah pakatan harapan (PH), former chairman of sabah democratic action party (DAP)

- Vivian Wong Shir Yee: Member of parliament for sandakan, vice chief of sabah democratic action party socialist youth (DAPSY)

- Poon Ming Fung: Former minister of people's health and wellbeing sabah, former minister of youth and sports sabah, member of sabah state legislative assembly for tanjong papat, acting chairman of sabah democratic action party (DAP)

- Hiew Vun Zin: Former assistant minister of housing and local government sabah, member of sabah state legislative assembly for karamunting, chief of sabah heritage party for sandakan (WARISAN)

- Arunarsin Taib: Former assistant minister of youth and sports sabah, member of sabah state legislative assembly for gum-gum

- Entertainment

- Fung Bo Bo: Hong Kong actress

- Sports

See also

- Sandakan No. 8

References

- "Malaysia Elevation Map (Elevation of Sandakan)". Flood Map : Water Level Elevation Map. Archived from the original on 22 August 2015. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- "Total population by ethnic group, Local Authority area and state, Malaysia, 2010" (PDF). Department of Statistics Malaysia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/uploads/files/6_Newsletter/Newsletter%202020/DOSM_DOSM_SABAH_1_2020_Siri-86.pdf

- "Founding of Sandakan". Sabah State Government. Archived from the original on 9 June 2015. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- Vern Bouwman (2004). Navy Super Tankers. Trafford Publishing. pp. 270–. ISBN 978-1-4120-3206-3.

- Wendy Hutton (November 2000). Adventure Guides: East Malaysia. C. E. Tuttle. pp. 86–. ISBN 978-962-593-180-7.

- James Alexander (2006). Malaysia, Brunei and Singapore. New Holland Publishers. pp. 378–. ISBN 978-1-86011-309-3. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- Tamara Thiessen (2008). Borneo. Bradt Travel Guides. pp. 199–. ISBN 978-1-84162-252-1.

- Danny T.K. Wong. "KEBUN CINA : AN EARLY CHINESE SUBURBAN SETTLEMENT IN SANDAKAN". Sandakan Rainforest Park. Archived from the original on 27 March 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- Wendy Hutton (1 January 2004). Sandakan: History, Culture, Wildlife, and Resorts of the Sandakan Peninsula. Natural History Publications (Borneo). ISBN 978-983-812-084-5.

- Ranjit Singh (2000). The Making of Sabah, 1865–1941: The Dynamics of Indigenous Society. University of Malaya Press. ISBN 978-983-100-095-3. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- "AHLI DEWAN UNDANGAN NEGERI". Sabah State Government. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- Cyril Lim (11 July 2013). "How Sandakan became Little Philippines". Free Malaysia Today. Archived from the original on 28 March 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- "Opening of Hotel and Mall marks the return of "Little Hong Kong" for Sandakan". IREKA Corporation Sdn Bhd. Archived from the original on 7 June 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- Mohd. Jamil Al-Sufri (Pehin Orang Kaya Amar Diraja Dato Seri Utama Haji Awang.); K. Agustinus; Mohd. Amin Hassan (2002). Survival of Brunei: a historical perspective. Brunei History Centre, Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sports. ISBN 9789991734187.

- Frans Welman (9 March 2017). Borneo Trilogy Volume 1: Sabah. Booksmango. pp. 160–. ISBN 978-616-245-078-5.

- Ben Cahoon. "Sabah". worldstatesmen.org. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

Sultan of Brunei cedes the lands east of Marudu Bay to the Sultanate of Sulu in 1704.

- Liz Price (20 October 2007). "Sandakan, colonial capital of Sabah". The Brunei Times. Archived from the original on 3 October 2016. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- James Francis Warren (1981). The Sulu Zone, 1768–1898: The Dynamics of External Trade, Slavery, and Ethnicity in the Transformation of a Southeast Asian Maritime State. NUS Press. pp. 114–122. ISBN 978-9971-69-004-5. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- Leigh R. Wright (1 July 1988). The Origins of British Borneo. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 134–. ISBN 978-962-209-213-6.

- Johan M. Padasian: Sabah History in pictures (1881–1981), Sabah State Government, 1981

- Albert C. K. Teo; Junaidi Payne (1992). A Guide to Sandakan Sabah, Malaysia. the author. ISBN 978-983-99612-2-5. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- "Sabah Early History". Sabah State Government. New Sabah Times. 6 December 2007. Archived from the original on 30 May 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

His first contingent of police was, therefore, made up of Indian Sikhs whose stature alone must have been quite frightening to some of the natives.

- Peter Firkins; Graham Donaldson. "The Japanese occupation of Sandakan, January 1942". Borneo Surgeon - A Reluctant Hero - The Story of Dr James P. Taylor. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- Dr Richard Reid. "Sandakan". Laden, Fevered, Starved - The POWs of Sandakan, North Borneo, 1945. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- Paul Ham (2012). Sandakan: The Untold Story of the Sandakan Death Marches. Random House Australia. ISBN 978-1-86471-140-0. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- Alexander Mikaberidze (25 June 2013). Atrocities, Massacres, and War Crimes: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 752–. ISBN 978-1-59884-926-4.

- Michele Cunningham (30 July 2013). Hell on Earth: Sandakan – Australia's greatest war tragedy. Hachette Australia. pp. 193–. ISBN 978-0-7336-2930-3.

- Tash Impey (1 June 2011). "Tracing Sandakan's deadly footsteps". ABC News. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- Charles de Ledesma; Mark Lewis; Pauline Savage (2003). Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei. Rough Guides. pp. 548–. ISBN 978-1-84353-094-7.

- Ismail Ali. "The Role and Contribution of the British Administration and the Capitalist in the North Borneo Fishing Industry, 1945–63" (PDF). Pascasarjana Unipa Surabaya. pp. 1–3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2015. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

The Crown Colony administration chose Jesselton, now known as Kota Kinabalu, as its new centre of administration and the new capital. This decision was made owing to the devastating damage suffered by Sandakan as mentioned previously and the ever growing development of the rubber industry along the Western residential coast of North Borneo. Although Sandakan is no longer the capital city, it remained as the "economic capital of the state" for North Borneo, specifically as a port which handles activities pertaining to the export of timber and other agricultural products from the eastern coast of North Borneo. While, the fishing industry at the final stages of the British administration era saw a great involvement by the Hong Kong "towkays" to the prawn commodity around the coasts of Kudat, Sandakan and up Tambisan. For example, in 1951 the British administration granted an Hong Kong based Chun-Li Company to operate prawn industry in the North Borneo waters.

- "Sister and Friendship Cities". Burwood Council. 17 August 2012. Archived from the original on 27 March 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- Raymond Tan Shu Kiah (19 June 2000). "The Seminar on Twin City – Sandakan and Zamboanga". Virtual Office of Datuk Raymond Tan Shu Kiah. Archived from the original on 14 April 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- "Sandakan Profile". Sandakan Municipal Council. Archived from the original on 2 April 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- "Sea curfew in Sabah to be extended until Sept 2, say cops". The Star. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- "Sabah Sea Port". Borneo Trade. Archived from the original on 16 August 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- "Sandakan to Kota Kinabalu Distance". Google Maps. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- "Physical Plan Area Sandakan District". Town and Regional Planning Department, Sabah. Archived from the original on 9 June 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- "Sabah District Map". Department of Lands and Surveys, Sabah. Archived from the original on 9 June 2015. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- Vu Hai Dang (9 January 2014). Marine Protected Areas Network in the South China Sea: Charting a Course for Future Cooperation. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 147–. ISBN 978-90-04-26635-3.

- P. Thomas; F. K. C. Lo; A. J. Hepburn (1976). The land capability classification of Sabah. Land Resources Division, Ministry of Overseas Development.

- P. Thomas; F. K. C. Lo; A. J. Hepburn (1976). "The land capability classification of Sabah (Volume 2) – The Sandakan Residency (Climate)" (PDF). Land Resources Division, Ministry of Overseas Development. p. 7/22. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- "Sandakan Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- "Station Sandakan" (in French). Meteo Climat. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- "Klimatafel von Sandakan / Insel Borneo (Kalimantan) / Malaysia" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- Kamal Sadiq (2 December 2008). Paper Citizens: How Illegal Immigrants Acquire Citizenship in Developing Countries. Oxford University Press. pp. 48–. ISBN 978-0-19-970780-5.

- Brookfield, Harold; Yvonne, Bryon; Potter, L (1995). In Place of the Forest; Environmental and Socio-Economic Transformation in Borneo and the Eastern Malay Peninsula. United Nations University Press. p. 24. ISBN 92-808-0893-1. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

Orang Asli of the Peninsula or the Dayak, Kadazan, Murut, and Orang Ulu of Borneo were converted to Islam

- Sintang, Suraya; Khambali, Khadijah Mohd; Baharuddin, Azizan; Ahmad, Mahmud (2011). "Interfaith marriage and religious conversions: A case study of muslim converts in Sabah, Malaysia". International Conference on Behavioral, Cognitive and Psychological Sciences (BCPS 2011). 23: 170–176. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

TABLE III indicates the number of Muslim converts all over districts of Sabah within eight years beginning from the year 2000-2007. The city of Kota Kinabalu states the highest number of conversion (3526), then followed by Keningau (1307), Sandakan (1051), Tawau (829), Ranau (741) and Lahad Datu (714).

- Sintang, Suraya; Khambali, Khadijah Mohd; Baharuddin, Azizan; Ahmad, Mahmud (2011). Interfaith marriage and religious conversions: A case study of muslim converts in Sabah, Malaysia. Maldives: IACSIT Press. Archived from the original on 8 June 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- "PEOPLE OF SABAH". Discovery Tours Sabah. Archived from the original on 28 March 2014. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- Stephen Adolphe Wurm; Peter Mühlhäusler; Darrell T. Tyron (1996). Atlas of Languages of Intercultural Communication in the Pacific, Asia, and the Americas. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 1615–. ISBN 978-3-11-013417-9.

- Jurnal bahasa moden. Pusat Bahasa, Universiti Malaya. 1991.

- Miller, Mark Turner (2007). A Grammar of West Coast Bajau (Ph.D. thesis). University of Texas at Arlington. pp. 5–. hdl:10106/577.

- Julie K. King; John Wayne King (1984). Languages of Sabah: Survey Report. Department of Linguistics, Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-85883-297-8.

- Borneo. Ediz. Inglese. Lonely Planet. 2008. pp. 133–. ISBN 978-1-74059-105-8.

- "Introduction and History of Sandakan". Sabah Education.net. Archived from the original on 25 March 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- Danny Wong Tze-Ken (1999). "Chinese Migration to Sabah Before the Second World War". Archipel. pp. 135–136. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- "Sandakan poised to become business hub". The Borneo Post. 12 April 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- Europa Publications (September 2002). Europa World Year Book. Europa Publications. ISBN 978-1-85743-129-2.

- "Barter Trading in Sandakan". Sabah State Government. Archived from the original on 1 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- "Industrial Zones in Sandakan". Sabah State Government. Archived from the original on 1 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- "RM367 mln road upgrade projects in Sandakan". The Borneo Post. 2 December 2012. Archived from the original on 28 July 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- "Majulah Industrial Centre". Marico Realty. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- "Majulah Industrial Centre". Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- Dr. B. Beth Baikan. "Summary of Issues From The Sandakan District Coastal Zone Profile". Sabah ICZM Local Consultant. Town and Regional Planning Department, Sabah. Archived from the original on 25 March 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- "Sabah to launch massive operation against illegal immigrants". The Sun. 19 August 2013. Archived from the original on 25 March 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- "Transport (Road Networks)". Town and Regional Planning Department, Sabah. Archived from the original on 29 March 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- "RM367 mln road upgrade projects in Sandakan". The Borneo Post. 2 December 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- "INFRASTRUCTURE & SUPERSTRUCTURE (Road)". Borneo Trade (Source from Public Works Department, Sabah). Archived from the original on 27 February 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- "The Long Distance Bus Service in Sabah (Sandakan)" (PDF). MySabah.com. p. 12. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- Lonely Planet; Simon Richmond; Cristian Bonetto; Celeste Brash, Joshua Samuel Brown, Austin Bush, Adam Karlin, Shawn Low, Daniel Robinson (1 April 2013). Lonely Planet Malaysia Singapore & Brunei. Lonely Planet. pp. 777–. ISBN 978-1-74321-633-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Sandakan Town Map" (PDF). SabahExpress.com. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- "Philippines: Asian Spirit set to revive Zambo-Sandakan route". Davao Today. 25 April 2007. Archived from the original on 29 March 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- Paolo G. Montecillo (21 January 2013). "AirPhil Express eyes flights to Sabah". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 29 March 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- "RM70mil allocation to upgrade Sandakan airport." Bernama. The Star. 13 January 2013. Archived from the original on 29 March 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- MobileReference (January 0101). Travel Philippines. MobileReference. pp. 110–. ISBN 978-1-61198-276-3.

- "Ferry Terminal (Sandakan)". Sabah State Government. Archived from the original on 29 March 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- "Fighting puts stop to ferry service". New Straits Times. 13 September 2013. Archived from the original on 29 March 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- "Closure of Filipino refugee camps in Malaysia sought". GMA Network. 19 April 2007. Archived from the original on 29 March 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- Yong Teck Lee (2 February 2002). "SCRAP FERRY SERVICES: YONG". Sabah.org.my. Archived from the original on 29 March 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- "Official Website of The High Court in Sabah & Sarawak". judiciary.kehakiman.gov.my. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- "Syariah Courts Address in Sabah". Department of Sabah State Syariah. Archived from the original on 21 April 2014. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- "Sandakan District Police Headquarters". Google Maps. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- "Sandakan Town Map". Wonderful Malaysia. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- "Direktori: Alamat dan telefon PDRM". Royal Malaysian Police. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- "Penjara Sandakan (Alamat & Telefon Penjara)". Prison Department of Malaysia. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- "16 Social Facilities". Town and Regional Planning Department, Sabah. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- "Clinics in Sandakan". Sabah State Health Department. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- "Sejarah Hospital" (in Malay). Duchess of Kent Hospital. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

At present, the hospital possesses 400 beds, including 18 beds for intensive care.

- "Non-profit hospital for Sandakan". The Star. 28 June 2008. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- "Two applications from Sabah for establishment of private hospitals". New Sabah Times. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- "Sandakan Regional Library". Sabah State Library Online. Archived from the original on 31 March 2014. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- "Catholic Mission Schools in Sandakan". Archived from the original on 9 June 2015. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- "SENARAI SEKOLAH MENENGAH DI NEGERI SABAH (List of Secondary Schools in Sabah) – See Sandakan" (PDF). Educational Management Information System. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- "KTS raises fund for Sandakan school". The Borneo Post. 16 September 2012. Archived from the original on 31 March 2014. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- "Sandakan Heritage Museum". Sabah Museum. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- "Cultural experience at its best at Sandakan Festival". The Brunei Times. 25 April 2012. Archived from the original on 1 April 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- "Sandakan Festival (until June 7)". New Straits Times. 6 June 2006. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- "Agnes Keith House, Sandakan". Sabah Museum. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- "Tersimpan 1,001 rahsia di sebalik nama Bukit Maria". Utusan Borneo (in Malay). PressReader. 1 December 2017. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- "Sandakan Heritage Trails" (PDF). Borneo Sandakan Tours Sdn. Bhd. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- Awang Ali Omar (27 November 2017). "Marian Hill set to charm tourists with its unique attractions". New Straits Times. Yahoo! News. Archived from the original on 28 November 2017. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- "Tourist Spots". Sabah Education. Archived from the original on 1 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- "Sandakan, Sabah: Into the Wild" (PDF). Citizen. July–September 2010. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- "Sanctuary for Marine Turtles". Sabah Parks. Turtle Islands Park. Archived from the original on 1 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- Tan Hee Hui (26 July 2009). "Eclecticism in splendor". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 1 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- "Harbour Mall opens for business, predicted to be Sabah's next shopping haven". New Sabah Times. 17 July 2012. Archived from the original on 13 June 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- Lawrence Shim (27 July 2011). "Sandakan Harbour Square a boost to Sandakan tourism". The Borneo Post. Archived from the original on 2 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- "Sejati Walk to be Sandakan's latest shopping destination". Daily Express. 17 January 2014. Archived from the original on 2 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- "Sejati Walk, Sandakan launched". Daily Express. 19 January 2014. Archived from the original on 2 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- Eddie Butler (9 November 2008). "Hard-nosed rugby men stick out among the proboscis monkeys". The Observer. Archived from the original on 1 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- "Yang Di-Pertua Negeri". Sabah State Government. Archived from the original on 2 April 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- Roy Goh (23 December 2012). "Parties use town as 'power base'". New Straits Times – via HighBeam (subscription required) . Archived from the original on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "Alex Lim". California Golden Bears. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- "Sandakan boys to men". New Straits Times. 20 December 1999. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

External links

Sandakan travel guide from Wikivoyage

Sandakan travel guide from Wikivoyage- Sandakan Municipal Council

.jpg.webp)

.svg.png.webp)