Santiago

Santiago (/ˌsæntiˈɑːɡoʊ/, US also /ˌsɑːn-/;[2] Spanish: [sanˈtjaɣo]), also known as Santiago de Chile (IPA: [sanˈtjaɣo ðe ˈt͡ʃile]), is the capital and largest city of Chile as well as one of the largest cities in the Americas. It is the center of Chile's most densely populated region, the Santiago Metropolitan Region, whose total population is 8 million which is nearly 40% of the country's population, of which more than 6 million live in the city's continuous urban area. The city is entirely in the country's central valley. Most of the city lies between 500–650 m (1,640–2,133 ft) above mean sea level.

Santiago | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Left to right, from top to bottom. I row: Panoramic of Santiago. II row: Statue of the Immaculate Conception and Santiago's financial district. III row: Santa Lucía Hill and National Library of Chile. IV row: University of Chile and Pontifical Catholic University of Chile. V row: La Moneda Palace. | |

Flag .svg.png.webp) Coat of arms

Santiago Location in Chile  Santiago Santiago (South America) | |

| Nickname: "The City of the Island Hills" | |

| Coordinates: 33°27′S 70°40′W | |

| Country | Chile |

| Region | Santiago Metropolitan Region |

| Province | Santiago Province |

| Foundation | 12 February 1541 |

| Founded by | Pedro de Valdivia |

| Named for | Saint James |

| Area | |

| • Capital city | 641 km2 (247.6 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 570 m (1,870 ft) |

| Population (2017) | |

| • Capital city | 6,269,384 |

| • Density | 9,821/km2 (25,436/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 6,903,479 |

| Demonym | Santiaguinos (-as) |

| Time zone | UTC−4 (CLT) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−3 (CLST) |

| Postal code | 8320000 |

| Area code | +56 2 |

| HDI (2019) | 0.883[1] – very high |

| Website | Official website |

Founded in 1541 by the Spanish conquistador Pedro de Valdivia, Santiago has been the capital city of Chile since colonial times. The city has a downtown core of 19th-century neoclassical architecture and winding side-streets, dotted by art deco, neo-gothic, and other styles. Santiago's cityscape is shaped by several stand-alone hills and the fast-flowing Mapocho River, lined by parks such as Parque Forestal and Balmaceda Park. The Andes Mountains can be seen from most points in the city. These mountains contribute to a considerable smog problem, particularly during winter, due to the lack of rain. The city outskirts are surrounded by vineyards and Santiago is within an hour of both the mountains and the Pacific Ocean.

Santiago is the political and financial center of Chile and is home to the regional headquarters of many multinational corporations. The Chilean executive and judiciary are located in Santiago, but Congress meets mostly in nearby Valparaíso. Santiago is named after the biblical figure Saint James. The city will host the 2023 Pan American Games.[3]

Nomenclature

In Chile, there are several entities which have the name of "Santiago" that are often confused. The commune of Santiago, sometimes referred to as "Downtown/Central Santiago" (Santiago Centro), is an administrative division that comprises roughly the area occupied by the city during its colonial period. The commune, administered by the Municipality of Santiago and headed by a mayor, is part of the Santiago Province headed by a provincial delegate, which is in itself a subdivision of the Santiago Metropolitan Region headed by a governor. While the mayor and governor are elected by popular vote, the provincial delegate is designated by the President of the Republic as its local representative.

Despite these classifications, when the term "Santiago" is used without another descriptor, it usually refers to what is also known as Greater Santiago (Gran Santiago), the metropolitan area defined by its urban continuity that includes the commune of Santiago and more than 40 other communes, which together comprise the majority of the Santiago Province and some areas of neighboring provinces (see Political divisions). The definition of this metropolitan area has evolved due to the continuing expansion of the city and the absorption of smaller cities and rural areas.

The name of "Santiago" originates in the name chosen by the Spanish conqueror, Pedro de Valdivia, when he founded the city in 1541. Valdivia honored James the Great, the patron saint of Spain. In the Spanish language, the name of this saint is rendered in different ways, as Diego, Jaime, Jacobo or Santiago; the latter is derived from the Galician evolution of Vulgar Latin Sanctu Iacobu. There is no indigenous name for the area occupied by Santiago; Mapuche language uses the name "Santiaw" as an adaptation of the Spanish name of the city.

When founded, Valdivia used the name "Santiago del Nuevo Extremo" or "Nueva Extremadura", based on the territory he expected to colonize and that he named honoring his native Extremadura. The name didn't persist for long and was eventually replaced by the local name of Chile. To differentiate with other cities called Santiago, the South American city is sometimes called "Santiago de Chile" in Spanish and other languages.

The city and region's demonym is santiaguinos (male) and santiaguinas (female).

History

Prehistory

According to certain archeological investigations, it is believed that the first human groups reached the Santiago basin in the 10th millennium BC. The groups were mainly nomadic hunter-gatherers, who traveled from the coast to the interior in search of guanacos during the time of the Andean snowmelt. About the year 800, the first sedentary inhabitants began to settle due to the formation of agricultural communities along the Mapocho River, mainly maize, potatoes and beans, and the domestication of camelids in the area.

The villages established in the areas belonging to the Picunches (the name given by Chileans) or Promaucae people (name given by the Incas), were subject to the Inca Empire throughout the late fifteenth century and into the early sixteenth century. The Incas settled in the valley of mitimas, the main installation settled in the center of the present city, with strongholds such as Huaca de Chena and the sanctuary of El Plomo hill. The area would have served as a basis for the failed Inca expeditions southward road junction as the Inca Trail.

Founding of the city

Painting by Pedro Lira, the portrait of Pedro de Valdivia and Juan Martín de Candia;[4] proclaiming the City of Santiago de Chile, c. 1541

Having been sent by Francisco Pizarro from Peru and having made the long journey from Cuzco, Extremadura conquistador Pedro de Valdivia reached the valley of the Mapocho on 13 December 1540. The hosts of Valdivia camped by the river in the slopes of the Tupahue hill and slowly began to interact with the Picunche people who inhabited the area. Valdivia later summoned the chiefs of the area to a parliament, where he explained his intention to found a city on behalf of the king Carlos I of Spain, which would be the capital of his governorship of Nueva Extremadura. The natives accepted and even recommended the foundation of the town on a small island between two branches of the river next to a small hill called Huelén.

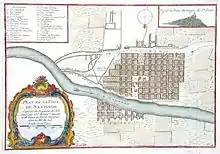

On 12 February 1541 Valdivia officially founded the city of Santiago del Nuevo Extremo (Santiago of New Extremadura) near the Huelén, renamed by the conqueror as Santa Lucia. Following colonial rule, Valdivia entrusted the layout of the new town to master builder Pedro de Gamboa, who would design the city grid layout. In the center of the city, Gamboa designed a Plaza Mayor, around which various plots for the Cathedral and the governor's house were selected. In total, eight blocks from north to south, and ten from east to west, were built. Each solar (quarter block) was given to the settlers, who built houses of mud and straw.

Valdivia left months later to the south with his troops, beginning the War of Arauco. Santiago was left unprotected. The indigenous hosts of Michimalonco used this to their advantage, and attacked the fledgling city. On 11 September 1541, the city was destroyed by the natives, but the 55-strong Spanish Garrison managed to defend the fort. The resistance was led by Inés de Suárez, a mistress to Valdivia. When she realized they were being overrun, she ordered the execution of all native prisoners, and proceeded to put their heads on pikes and also threw a few heads to the natives. In face of this barbaric act, the natives dispersed in terror. The city would be slowly rebuilt, giving prominence to the newly founded Concepción, where the Royal Audiencia of Chile was then founded in 1565. However, the constant danger faced by Concepción, due partly to its proximity to the War of Arauco and also to a succession of devastating earthquakes, would not allow the definitive establishment of the Royal Court in Santiago until 1607. This establishment reaffirmed the city's role as capital.

During the early years of the city the Spanish suffered from severe shortages of food and other supplies. The cause of this was a strategy by the local indigenous Picunche to stop cultivation and retreat to more distant places.[5] Isolated from reinforcements the Spanish had to resort to eat whatever they found, lack of clothes meant some Spanish came to dress with hides from dogs, cats, sea lions and foxes.[5]

Colonial Santiago

Although early Santiago appeared to be in imminent danger of permanent destruction, threatened by Indigenous attacks, earthquakes, and a series of floods, the city began to grow rapidly. Of the 126 blocks designed by Gamboa in 1558, 40 were occupied, and in 1580, the first major buildings in the city began to rise, the start of construction highlighted with the placing of the foundation stone of the first Cathedral in 1561 and the building of the church of San Francisco in 1572. Both of these constructions consisted of mainly adobe and stone. In addition to construction of important buildings, the city began to develop as nearby lands welcomed tens of thousands of livestock.

A series of disasters impeded the development of the city during the 16th and 17th centuries: an earthquake, a 1575 smallpox epidemic, in 1590, 1608, and 1618, the Mapocho River floods, and, finally, the earthquake of 13 May 1647, which killed over 600 people and affected more than 5,000 others. However, these disasters would not stop the growth of the capital of the Captaincy General of Chile at a time when all the power of the country was centered on the Plaza de Armas santiaguina.

In 1767, the corregidor Luis Manuel de Zañartu, launched one of the most important architectural works of the entire colonial period, Calicanto Bridge, effectively connecting the city to La Chimba on the north side of the river, and began the construction of embankments to prevent overflows of the Mapocho River. Although its builders were able to complete the bridge, the piers were constantly being damaged by the river. In 1780, Governor Agustín de Jáuregui hired the Italian architect Joaquín Toesca, who would design, among other important works, the façade of the cathedral, the Palacio de La Moneda, the canal San Carlos, and the final construction of the embankments during the government of Ambrosio O'Higgins. These important works were opened permanently in 1798. The O'Higgins government also oversaw the opening of the road to Valparaíso in 1791, which connected the capital with the country's main port.

Capital of the Republic

18 September 1810 was proclaimed the First Government Junta in Santiago, beginning the process of establishing the independence of Chile. The city, which became the capital of the new nation, was threatened by various events, especially the nearby military actions.

Although some institutions, such as the National Institute and the National Library, were installed in the Patria Vieja, they were closed after the patriot defeat at the Battle of Rancagua in 1814. The royal government lasted until 1817, when the Army of the Andes secured victory in battle of Chacabuco, reinstating the patriot government in Santiago. Independence, however, was not assured. The Spanish army gained new victories in 1818 and headed for Santiago, but their march was definitively halted on the plains of the Maipo River, during the Battle of Maipú on 5 April 1818.

With the end of the war, Bernardo O'Higgins was accepted as Supreme Director and, like his father, began a number of important works for the city. During the call Patria Nueva, closed institutions reopened. The General Cemetery opened, work on the canal San Carlos was completed, and, in the south arm of the Mapocho River, known as La Cañada, the drying riverbed, used for sometime as a landfill, was turned into an avenue, now known as the Alameda de las Delicias.

Two new earthquakes hit the city, one on 19 November 1822, and another on 20 February 1835. These two events, however, did not prevent the city's rapid, continued growth. In 1820 the city reported 46,000 inhabitants, while in 1854, the population reached 69,018. In 1865, the census reported 115,337 inhabitants. This significant increase was the result of suburban growth to the south and west of the capital, and in part to La Chimba, a vibrant district growing from the division of old properties that existed in the area. This new peripheral development led to the end of the traditional checkerboard structure that previously governed the city center.

19th century

During the years of the Republican era, institutions such as the University of Chile (Universidad de Chile), the Normal School of Preceptors, the School of Arts and Crafts, and the Quinta Normal, which included the Museum of Fine Arts (now Museum of Science and Technology) and the National Museum of Natural History, were founded. Created primarily for educational use, they also became examples of public planning during that period. In 1851 the first telegraph system connecting the capital with the Port of Valparaíso was inaugurated.[6]

A new momentum in the urban development of the capital took place during the so-called "Liberal Republic" and the administration of Mayor Benjamín Vicuña Mackenna. Among the main works during this period are the remodeling of the Cerro Santa Lucía which, despite its central location, had been in a state of poor repair.[6] In an effort to transform Santiago, Vicuña Mackenna began construction of the Camino de Cintura, a road surrounding the entire city. A new redevelopment of the Alameda Avenue turned it into the main road of the city.

Also during this time and with the work of European landscapers in 1873, O'Higgins Park came into existence. The park, open to the public, became a landmark in Santiago due to its large gardens, lakes, and carriage trails. Other important buildings were opened during this era, such as the Teatro Municipal opera house, and the Club Hípico de Santiago. At the same time, the 1875 International Exposition was held in the grounds of the Quinta Normal.[7]

The city became the main hub of the national railway system. The first railroad reached the city on 14 September 1857, at the Santiago Estación Central railway station. Under construction at the time, the station would be opened permanently in 1884. During those years, railways connected the city to Valparaíso as well as regions in the north and south of Chile. The streets of Santiago were paved and by 1875 there were 1,107 railway cars in the city, while 45,000 people used tram services on a daily basis.

The centennial Santiago

With the arrival of the new century, the city began to experience various changes related to the strong development of industry. Valparaíso, which had hitherto been the economic center of the country slowly lost prominence at the expense of the capital. By 1895, 75% of the national manufacturing industry was in the capital and only 28% in the harbor city, and by 1910, major banks and shops were set up in the streets of the city center, leaving Valparaíso.

The enactment of the Autonomous Municipalities' act allowed municipalities to create various administrative divisions around the then Santiago departamento, with the aim of improving local ruling. Maipú, Ñuñoa, Renca, Lampa and Colina were to be created in 1891, Providencia and Barrancas in 1897, and Las Condes in 1901. The La Victoria departamento was split with the creation of Lo Cañas in 1891, which would be split into La Granja and Puente Alto in 1892, La Florida in 1899, and La Cisterna in 1925.

The San Cristobal Hill in this period began a long process of development. In 1903 an astronomical observatory was installed and the following year the first stone was placed for its 14-meter Virgin Mary statue, nowadays visible from various points of city. However, the shrine would not be completed until some decades later.

With the 1910 Chile Centennial celebrations, many urban projects were undertaken. The railway network was extended allowing connection of the city with its nascent suburbs by a new rail ring and route to the Cajón del Maipo, while a new railway station was built in the north of the city: the Mapocho Station. At the Mapocho river's southern side, the Parque Forestal was created and new buildings such as the Museum of Fine Arts, the Barros Arana public boarding school and the National Library were opened. In addition, the work would include a sewer system, covering about 85% of the urban population.

Population explosion

The 1920 census estimated the population of Santiago to be 507,296 inhabitants, equivalent to 13.6% of the population of Chile. This represented an increase of 52.5% from the census of 1907, i.e. an annual growth of 3.3%, almost three times the national figure. This growth was mainly due to the arrival of farmers from the south who came to work in factories and railroads which were under construction. However, this growth was experienced on the outskirts and not in the town itself.

During this time the downtown district was consolidated into a commercial, financial and administrative center, with the establishment of various portals and locales around Ahumada Street and a Civic District in the immediate surroundings of the Palace of La Moneda. The latter project involved the construction of various modernist buildings for the establishment of the offices of ministries and other public services, as well as commencing the construction of medium-rise buildings. On the other hand, the traditional inhabitants of the center began to migrate out of the city to more rural areas like Providencia and Ñuñoa, which hosted the oligarchy and the European immigrant professionals, and San Miguel for middle-class families. Furthermore, in the periphery villas were built various partners from various organizations of the time. Modernity expanded in the city, with the appearance of the first theaters, the extension of the telephone network and the opening of the Airport Los Cerrillos in 1928, among other advances.

The feeling that the early 20th century was an era of economic growth due to technological advances contrasted dramatically with the standard of living of lower social classes. The growth of the previous decades led to an unprecedented population explosion starting in 1929. The Great Depression caused the collapse of the nitrate industry in the north, leaving 60,000 unemployed, which added to the decline in agricultural exports, resulting in a total number for the unemployed to be about 300,000 nationwide. These unemployed workers saw Santiago and its booming industry as the only chance to survive. Many migrants arrived in Santiago with nothing and thousands had to survive on the streets due to the great difficulty in finding a place they could rent. Widespread disease, including tuberculosis, claimed the lives of hundreds of the homeless. Unemployment and living costs increased dramatically whilst the salaries of the population of Santiago fell.

The situation would change only several years later with a new industrial boom fostered by CORFO and the expansion of the state apparatus from the late 1930s. At this time, the aristocracy lost much of its power and the middle class, composed of merchants, bureaucrats and professionals, acquired the role of setting national policy. In this context, Santiago began to develop a substantial middle- and lower-class population, while the upper classes sought refuge in the districts of the capital. Thus, the old moneyed class trips to Cousino and Alameda Park, lost hegemony over popular entertainment venues such as the National Stadium emerged in 1938.

Greater Santiago

| 1940 | 1952 | 1960 | 1970 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barrancas | 100 | 223 | 792 | 1978 |

| Conchalí | 100 | 225 | 440 | 684 |

| La Granja | 100 | 264 | 1379 | 3424 |

| Las Condes | 100 | 197 | 506 | 1083 |

| Ñuñoa | 100 | 196 | 325 | 535 |

| Renca | 100 | 175 | 317 | 406 |

| San Miguel | 100 | 221 | 373 | 488 |

| Santiago | 100 | 104 | 101 | 81 |

In the following decades, Santiago continued to grow unabated. In 1940, the city accumulated 952,075 inhabitants, in 1952 this figure rose to 1,350,409 residents and the census of 1960 totaled 1,907,378 santiaguinos. This growth was reflected in the urbanization of rural areas on the periphery, where families of middle and lower class with stable housing were established: in 1930 the urban area had an area of 6500 hectares, which in 1960 reached 20,900 and in 1980 to 38,296. Although most of the communities continued to grow, it is mainly concentrated in outlying communities such as Barrancas to the west, Conchalí northern and La Cisterna and La Granja to the south. For the upper class, it began to approach the foothills of Las Condes and La Reina sector. The center, however, lost people leaving more space for the development of trade, banking and government.

Regulation of the growth only began to be implemented during the 1960s with the creation of various development plans for Greater Santiago, a concept that reflected the new reality of a much larger city. In 1958 the Intercommunal Plan of Santiago was released. The proposed scheme set a limit of 38 600 urban and semi hectares for a maximum population of 3,260,000 inhabitants, included plans for the construction of new avenues, like the Américo Vespucio Avenue and Panamericana route 5, and the expansion of 'industrial belts'. The celebration of the World Cup in 1962 gave new impetus to implement plans for city improvement. In 1966 the Santiago Metropolitan Park was established in the Cerro San Cristóbal, MINVU began eradicating shanty towns and building new homes. Finally, the Edificio Diego Portales was constructed in 1972.

In 1967 the new International Airport Pudahuel was opened, and, after years of discussion, in 1969 construction began on the Santiago Metro. The first phase ran beneath the western section of the Alameda and was opened in 1975. The Metro would become one of the most prestigious buildings in the city. In the following years it continued to expand, with two perpendicular lines in place by the end of 1978. Building telecommunications infrastructure was also an important development of this period, as reflected in the construction of the Torre Entel, which since its construction in 1975 has become one of the symbols of the capital and the tallest structure in the country for two decades.

After the coup of 1973 and the establishment of the military regime, major changes in urban planning did not take place until the 1980s, when the government adopted a neoliberal economic model. In 1979, the master plan was amended. The urban area was extended to more than 62 000 ha for real estate development. This created urban sprawl, especially in La Florida, with the city reaching 40 619 ha in size in the early 1990s. The 1992 census showed that Santiago had become the country's most populous municipality with 328,881 inhabitants. Meanwhile, a strong earthquake struck the city on 3 March 1985. Although it caused few casualties, it left many people homeless and destroyed many old buildings.

The metropolis in the early twenty-first century

.jpg.webp)

With the start of the transition to democracy in 1990, the city of Santiago had surpassed three million inhabitants, with the majority living in the south: La Florida was the most populous area, followed by Puente Alto and Maipú. The real estate development in these municipalities and others like Quilicura and Peñalolén largely came from the construction of housing projects for middle-class families. Meanwhile, high-income families moved into the foothills, now called Barrio Alto, increasing the population of Las Condes and giving rise to new communes like Vitacura and Lo Barnechea.

The Providencia Avenue area became an important commercial hub in the eastern sector. This development was extended to Barrio Alto, which became an attractive location for the construction of high-rise buildings. Major companies and financial corporations were established in the area, which gave rise to a thriving modern business center known as Sanhattan. The departure of these companies to Barrio Alto and the construction of shopping centers all around the city created a crisis in the city center. To reinvent the area, the main shopping streets were turned into pedestrian walkways, such as the Paseo Ahumada, and the government instituted tax benefits for the construction of residential buildings, which attracted young adults.

The city began to face a series of problems generated by disorganized growth. Air pollution reached critical levels during the winter months and a layer of smog settled over the city. The authorities adopted legislative measures to reduce industrial pollution and placed restrictions on vehicle use. The Metro was expanded considerably, lines were extended and three new lines were built between 1997 and 2006 in the southeastern sector. A new extension to Maipú was inaugurated in 2011, at which point the metropolitan railway had a total length of 105 km. In the case of buses, the system underwent a major reform in the early 1990s. In 2007 the master plan known as Transantiago was established. It has faced a number of problems since its launch.

Entering the twenty-first century, rapid development continued in Santiago. The Civic District was renewed with the creation of the Plaza de la Ciudadanía and construction of the Ciudad Parque Bicentenario to commemorate the bicentenary of the Republic. The development of tall buildings continues in the eastern sector, which culminated in the opening of the skyscrapers Titanium La Portada and Gran Torre Santiago in the Costanera Center complex. However, socioeconomic inequality and geosocial fragmentation remain two of the most important problems in both the city and the country.

On 27 February 2010, a strong earthquake struck the capital, causing some damage to older buildings. However, some modern buildings were also rendered uninhabitable, generating much debate about the actual implementation of mandatory earthquake standards in the modern architecture of Santiago.

Geography

The city lies in the center of the Santiago Basin, a large bowl-shaped valley consisting of broad and fertile lands surrounded by mountains. The city has a varying elevation, gradually increasing from 400 m (1,312 ft) in the western areas to more than 700 m (2,297 ft) in the eastern areas. Santiago's international airport, in the west, lies at an altitude of 460 m (1,509 ft). Plaza Baquedano, near the center, lies at 570 m (1,870 ft). Estadio San Carlos de Apoquindo, at the eastern edge of the city, has an elevation of 960 m (3,150 ft).

The Santiago Basin is part of the Intermediate Depression and is remarkably flat, interrupted only by a few "island hills;" among them are Cerro Renca, Cerro Blanco, and Cerro Santa Lucía. The basin is approximately 80 kilometers (50 miles) in a north–south direction and 35 km (22 mi) from east to west. The Mapocho River flows through the city.

The city is flanked by the main chain of the Andes to the east and the Chilean Coastal Range to the west. On the north, it is bordered by the Cordón de Chacabuco, a mountain range of the Andes. At the southern border lies the Angostura de Paine, an elongated spur of the Andes that almost reaches the coast.

The mountain range immediately bordering the city on the east is known as the Sierra de Ramón, which was formed due to tectonic activity of the San Ramón Fault. This range reaches 3296 meters at Cerro de Ramón. The Sierra de Ramón represents the "Precordillera" of the Andes. 20 km (12 mi) further east is the even larger Cordillera of the Andes, which has mountains and volcanoes that exceed 6,000 m (19,690 ft) and on which some glaciers are present. The tallest is the Tupungato mountain at 6,570 m (21,555 ft). Other mountains include Tupungatito, San José, and Maipo. Cerro El Plomo is the highest mountain visible from Santiago's urban area.

During recent decades, urban growth has outgrown the boundaries of the city, expanding to the east up the slopes of the Andean Precordillera. In areas such as La Dehesa, Lo Curro, and El Arrayan, urban development is present at over 1,000 meters of altitude.[9]

The natural vegetation of Santiago is made up of a thorny woodland of Vachellia caven (also known as Acacia caven and espinillo) and Prosopis chilensis in the west and an association of Vachellia caven and Baccharis paniculata in the east around the Andean foothills.[10]

.jpg.webp) Ski Center La Parva

Ski Center La Parva Santiago Metropolitan Park

Santiago Metropolitan Park Santiago in the winter

Santiago in the winter Santiago in the summer

Santiago in the summer

Climate

Santiago has a cool semi-arid climate (BSk according to the Köppen climate classification), with Mediterranean (Csb) patterns: warm dry summers (October to March) with temperatures reaching up to 35 °C (95 °F) on the hottest days; winters (April to September) are cool and humid, with cool to cold mornings; typical daily maximum temperatures of 14 °C (57 °F), and low temperatures near 0 °C (32 °F). In climate station of Quinta Normal (near downtown) the precipitation average is 341.8 mm, and in climate station of Tobalaba (in higher grounds near the Andes mountains) the precipitation average is 367.8 mm.

In the airport area of Pudahuel, mean rainfall is 276.9 mm (10.90 in) per year, about 80% of which occurs during the winter months (May to September), varying between 50 and 80 mm (1.97 and 3.15 in) of rainfall during these months. That amount contrasts with a very sunny season during the summer months between December and March, when rainfall does not exceed 4 mm (0.16 in) on average, caused by an anticyclonic dominance continued for about seven or eight months. There is significant variation within the city, with rainfall at the lower-elevation Pudahuel site near the airport being about 20 percent lower than at the older Quinta Normal site near the city center.

Santiago's rainfall is highly variable and heavily influenced by the El Niño Southern Oscillation cycle, with rainy years coinciding with El Niño events and dry years with La Niña events.[11] The wettest year since records began in 1866 was 1900 with 819.7 millimeters (32.27 in)[12] – part of a "pluvial" from 1898 to 1905 that saw an average of 559.3 millimeters (22.02 in) over eight years[13] incorporating the second wettest year in 1899 with 773.3 millimeters (30.44 in) – and the driest 1924 with 66.1 millimeters (2.60 in).[12] Typically there are lengthy dry spells even in the rainiest of winters,[11] intercepted with similarly lengthy periods of heavy rainfall. For instance, in 1987, the fourth wettest year on record with 712.1 millimeters (28.04 in), there was only 1.7 millimeters (0.07 in) in the 36 days between 3 June and 8 July,[14][15] followed by 537.2 millimeters (21.15 in) in the 38 days between 9 July and 15 August.[16]

Precipitation is usually only rain, as snowfall only occurs in the Andes and Precordillera, being rare in eastern districts, and extremely rare in most of the city.[17] In winter, the snow line is about 2,100 meters (6,890 ft), and it ranges from 1,500–2,900 meters (4,921–9,514 ft).[17] The city is affected only occasionally by snowfall. The period between 2000 and 2017 has been registered 9 snowfalls and only two have been measured in the central sector (2007 and 2017). The amount of snow registered in Santiago on 15 July 2017 ranged between 3.0 cm in Quinta Normal and 10.0 cm in La Reina (Tobalaba).[18]

Temperatures vary throughout the year from an average of 20 °C (68 °F) in January to 8 °C (46 °F) in June and July. In the summer days are very warm to hot, often reaching over 30 °C (86 °F) and a record high close to 38 °C (100 °F),[19] while nights are very pleasant and cool, at 11 °C (52 °F). During autumn and winter the temperature drops, and is slightly lower than 10 °C (50 °F). The temperature may even drop to 0 °C (32 °F), especially during the morning. The historic low of −6.8 °C (20 °F) was in July 1976.[20]

Santiago's location within a watershed is one of the most important factors determining the climate of the city. The coastal mountain range serves as a screen that stops the spread of maritime influence, contributing to the increase in annual and daily thermal oscillation (the difference between the maximum and minimum daily temperatures can reach 14 °C) and maintaining low relative humidity, close to an annual average of 70%. It also prevents the entry of air masses, with the exception of some coastal low clouds that penetrate to the basin through the river valleys.[21]

Prevailing winds are from the southwest, with an average of 15 km/h (9 mph), especially during the summer; the winter is less windy.

| Climate data for Comodoro Arturo Merino Benítez International Airport, Pudahuel, Santiago (1981–2010, extremes 1966–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 39.3 (102.7) |

37.2 (99.0) |

36.8 (98.2) |

34.5 (94.1) |

31.1 (88.0) |

26.7 (80.1) |

28.2 (82.8) |

29.9 (85.8) |

32.9 (91.2) |

33.3 (91.9) |

34.7 (94.5) |

35.0 (95.0) |

39.3 (102.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 29.9 (85.8) |

29.4 (84.9) |

27.5 (81.5) |

23.0 (73.4) |

18.3 (64.9) |

15.3 (59.5) |

14.7 (58.5) |

16.4 (61.5) |

18.7 (65.7) |

22.5 (72.5) |

25.9 (78.6) |

28.5 (83.3) |

22.5 (72.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 20.4 (68.7) |

19.5 (67.1) |

17.5 (63.5) |

13.7 (56.7) |

10.3 (50.5) |

8.3 (46.9) |

7.5 (45.5) |

8.9 (48.0) |

11.1 (52.0) |

14.1 (57.4) |

16.9 (62.4) |

19.3 (66.7) |

14.0 (57.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 12.0 (53.6) |

11.5 (52.7) |

9.9 (49.8) |

7.1 (44.8) |

4.7 (40.5) |

3.5 (38.3) |

2.5 (36.5) |

3.6 (38.5) |

5.4 (41.7) |

7.3 (45.1) |

9.1 (48.4) |

11.0 (51.8) |

7.3 (45.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 2.7 (36.9) |

1.2 (34.2) |

0.7 (33.3) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

−6.2 (20.8) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

0.7 (33.3) |

3.2 (37.8) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 0.4 (0.02) |

0.8 (0.03) |

6.1 (0.24) |

12.0 (0.47) |

46.1 (1.81) |

68.7 (2.70) |

62.5 (2.46) |

44.2 (1.74) |

20.1 (0.79) |

10.0 (0.39) |

4.6 (0.18) |

1.4 (0.06) |

276.9 (10.90) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 3.8 | 5.0 | 4.9 | 4.0 | 2.7 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 24.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 53.9 | 57.4 | 62.1 | 68.7 | 77.9 | 82.2 | 82.5 | 79.9 | 75.4 | 68.0 | 60.1 | 55.1 | 68.6 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 367 | 305 | 277 | 202 | 145 | 120 | 132 | 162 | 182 | 205 | 298 | 350 | 2,745 |

| Source 1: Dirección Meteorológica de Chile[22][23][20] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Ogimet (sun 1981–2010),[24] World Meteorological Organization (precipitation days and humidity 1981–2010)[25] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Quinta Normal, Santiago (1981–2010, extremes 1967–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 38.3 (100.9) |

35.9 (96.6) |

36.2 (97.2) |

33.9 (93.0) |

31.6 (88.9) |

27.3 (81.1) |

28.4 (83.1) |

31.0 (87.8) |

32.6 (90.7) |

33.4 (92.1) |

34.8 (94.6) |

37.3 (99.1) |

38.3 (100.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 30.1 (86.2) |

29.5 (85.1) |

27.4 (81.3) |

23.1 (73.6) |

18.5 (65.3) |

15.7 (60.3) |

15.3 (59.5) |

17.1 (62.8) |

19.5 (67.1) |

22.9 (73.2) |

26.1 (79.0) |

28.8 (83.8) |

22.8 (73.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 21.2 (70.2) |

20.3 (68.5) |

18.2 (64.8) |

14.4 (57.9) |

10.9 (51.6) |

9.0 (48.2) |

8.2 (46.8) |

9.8 (49.6) |

12.0 (53.6) |

15.0 (59.0) |

17.7 (63.9) |

20.1 (68.2) |

14.7 (58.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 13.3 (55.9) |

12.8 (55.0) |

11.4 (52.5) |

8.6 (47.5) |

6.4 (43.5) |

5.0 (41.0) |

3.9 (39.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

6.7 (44.1) |

8.6 (47.5) |

10.3 (50.5) |

12.2 (54.0) |

8.7 (47.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 7.2 (45.0) |

6.2 (43.2) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

3.1 (37.6) |

1.0 (33.8) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 0.6 (0.02) |

1.3 (0.05) |

6.1 (0.24) |

16.3 (0.64) |

55.5 (2.19) |

83.3 (3.28) |

75.9 (2.99) |

55.1 (2.17) |

27.2 (1.07) |

12.9 (0.51) |

6.2 (0.24) |

1.5 (0.06) |

341.8 (13.46) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 1.6 | 4.2 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 4.2 | 3.2 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 26.8 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 57 | 61 | 68 | 74 | 80 | 84 | 84 | 81 | 76 | 70 | 62 | 57 | 71 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 325 | 270 | 250 | 191 | 132 | 101 | 118 | 151 | 165 | 219 | 269 | 320 | 2,511 |

| Source 1: Dirección Meteorológica de Chile[23][20] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: World Meteorological Organization (precipitation days 1981–2010),[25] Ogimet (sun 1981–2010),[26] Deutscher Wetterdienst (humidity 1961–1990)[27][28] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Santiago (Los Cerrillos Airport), 1961-1990 normals | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 20.5 (68.9) |

19.6 (67.3) |

17.4 (63.3) |

14.2 (57.6) |

11.1 (52.0) |

8.5 (47.3) |

8.2 (46.8) |

9.4 (48.9) |

11.3 (52.3) |

14.1 (57.4) |

17.0 (62.6) |

19.4 (66.9) |

14.2 (57.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 0.3 (0.01) |

0.5 (0.02) |

3.1 (0.12) |

10.4 (0.41) |

42.4 (1.67) |

71.6 (2.82) |

84.1 (3.31) |

46.1 (1.81) |

22.5 (0.89) |

11.9 (0.47) |

10.1 (0.40) |

1.8 (0.07) |

304.8 (12) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 58 | 62 | 66 | 71 | 79 | 83 | 83 | 80 | 77 | 71 | 64 | 60 | 71 |

| Source: NOAA[29] | |||||||||||||

Natural disasters

Due to Santiago's location on the Pacific Ring of Fire at the boundary of the Nazca and South American plates, it experiences a significant amount of tectonic activity.[30] The first earthquake on record to strike Santiago occurred in 1575, 34 years after the official founding of Santiago. The 1647 Santiago earthquake devastated the city, and inspired Heinrich von Kleist's novel, The Earthquake In Chile.[30]

The 1960 Valdivia earthquake and the 1985 Algarrobo earthquake both caused damage in Santiago, and led to the development of strict building codes with a view to minimizing future earthquake damage. In 2010 Chile was struck by the sixth largest earthquake ever recorded, reaching 8.8 on the moment magnitude scale. 525 people died, of whom 13 were in Santiago, and the damage was estimated at 15–30 billion US dollars. 370,000 homes were damaged, but the building codes implemented after the earlier earthquakes meant that despite the size of the earthquake, damage was far less than that caused a few weeks earlier by the 2010 Haiti earthquake, in which at least 100,000 people died.[31] Large megathrust earthquakes aside, smaller local faults in an around Santiago pose significant earthquake risks.[32] Two faults in particular, San Ramón and El Arrayan, in the east and north of Santiago respectively have been singled out as being particularly dangerous.[32][33]

The easternmost neighborhoods of the city lies in a zone prone to landslides. Landslides of the debris flow type in particular are a significant hazard.[34]

Environmental issues

Santiago's air is the most polluted air in Chile.[35] In the 1990s air pollution fell by about one-third, but there has been little progress since 2000. A study by a Chilean university found in 2010 that pollution in Santiago had doubled since 2002.[36] Particulate matter air pollution is a serious public health concern in Santiago, with atmospheric concentrations of PM2.5 and PM10 regularly exceeding standards established by the US Environmental Protection Agency and World Health Organization.[37]

A final major source of Santiago air pollution, one that continues year-round, is the smelter of the El Teniente copper mine.[38][39] The government does not usually report it as being a local pollution source, as it is just outside the reporting area of the Santiago Metropolitan Region, being 110 kilometers (68 mi) from downtown.[40][41]

During winter months, thermal inversion (a meteorological phenomenon whereby a stable layer of warm air holds down colder air close to the ground) causes high levels of smog and air pollution to be trapped and concentrated within the Central Valley.

As of March 2007, only 61% of the wastewater in Santiago was treated,[42] which increased up to 71% by the end of the same year. However, in March 2012, the Mapocho Wastewater Treatment Plant began operations, increasing the wastewater treatment capacity of the city to 100%, making Santiago the first capital city in Latin America to treat all of its municipal sewage.[43]

Stray dogs are common in Santiago.[44][45] However, rabies is practically non-existent in Chile.[46]

Demographics

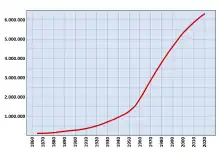

According to data collected in the 2002 census by the National Institute of Statistics, the Santiago metropolitan area population reached 5,428,590 inhabitants, equivalent to 35.9% of the national total and 89.6% of total regional inhabitants. This figure reflects broad growth in the population of the city during the 20th century: it had 383,587 inhabitants in 1907; 1,010,102 in 1940; 2,009,118 in 1960; 3,899,619 in 1982; and 4,729,118 in 1992.[47] (percentage of total population, 2007)[48]

The growth of Santiago has undergone several changes over the course of its history. In its early years, the city had a rate of growth 2.9% annually until the 17th century, then down to less than 2% per year until the early 20th century figures. During the 20th century, Santiago experienced a demographic explosion as it absorbed migration from mining camps in northern Chile during the economic crisis of the 1930s. The population surged again via migration from rural sectors between 1940 and 1960. This migration was coupled with high fertility rates, and annual growth reached 4.9% between 1952 and 1960. Growth has declined, reaching 1.4% in the early 2000s. The size of the city expanded constantly; The 20,000 hectares Santiago covered in 1960 doubled by 1980, reaching 64,140 hectares in 2002. The population density in Santiago is 8,464 inhabitants/km2.

The population of Santiago[47] has seen a steady increase in recent years. In 1990 the total population under 20 years was 38.0% and 8.9% were over 60. Estimates in 2007 show that 32.9% of men and 30.7% of women were less than 20 years old, while 10.2% of men and 13.4% of women were over 60 years. For the year 2020, it is estimated that the figures will be 26.7% and 16.8%.

4,313,719 people in Chile say they were born in one of the communes of the Santiago Metropolitan Region,[47] which, according to the 2002 census, amounts to 28.5% of the national total. 67.6% of the inhabitants of Santiago claim to have been born in one of the communes of the metropolitan area. In communes such as Santiago Centro and Independencia, according to 2017 census, 1/3 of residents is a Latin American immigrant (28% and 31% of the population of these communes, respectively).[49] Other communes of Greater Santiago with high numbers of immigrants are Estación Central (17%) and Recoleta (16%).[50]

Economy

Santiago is the industrial and financial center of Chile, and generates 45% of the country's GDP.[51] Some international institutions, such as ECLAC (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean), have their offices in Santiago. The strong economy and low government debt is attracting migrants from Europe and the United States.[52]

Santiago's steady economic growth over the past few decades has transformed it into a modern metropolis. The city is now home to a growing theater and restaurant scene, extensive suburban development, dozens of shopping centers, and a rising skyline, including the second tallest building in Latin America, the Gran Torre Santiago. It includes several major universities, and has developed a modern transportation infrastructure, including a free flow toll-based, partly underground urban freeway system and the Metro de Santiago, South America's most extensive subway system.

Santiago is an economically divided city (Gini coefficient of 0.47).[53][54] The western half (zona poniente) of the city is, on average, much poorer than the eastern communes, where the high-standard public and private facilities are concentrated.

Commercial development

The Costanera Center, a mega project in Santiago's Financial District, includes a 280,000-square-meter (3,000,000 sq ft) mall, a 300-meter (980 ft) tower, two office towers of 170 meters (558 ft) each, and a hotel 105 meters (344 ft) tall. In January 2009 the retailer in charge, Cencosud, said in a statement that the construction of the mega-mall would gradually be reduced until financial uncertainty is cleared.[55] In January 2010, Cencosud announced the restart of the project, and this was taken generally as a symbol of the country's success over the global financial crisis. Close to Costanera Center another skyscraper is already in use, Titanium La Portada, 190 meters (623 ft) tall. Although these are the two biggest projects, there are many other office buildings under construction in Santiago, as well as hundreds of high rise residential buildings. In February 2011, Gran Torre Santiago, part of the Costanera Center project, located in the called Sanhattan district, reached the 300-meter mark, officially becoming the tallest structure in Latin America.[56]

Commerce

Santiago is Chile's retail capital. Falabella, Paris, Johnson, Ripley, La Polar, and several other department stores dot the mall landscape of Chile. The east side neighborhoods like Vitacura, La Dehesa, and Las Condes are home to Santiago's Alonso de Cordova street, and malls like Parque Arauco, Alto Las Condes, Mall Plaza (a chain of malls present in Chile and other Latin American countries) and Costanera Center are known for their luxurious shopping. Alonso de Cordova, Santiago's equivalent to Rodeo Drive or Rua Oscar Freire in São Paulo, has exclusive stores like Louis Vuitton, Hermès, Emporio Armani, Salvatore Ferragamo, Ermenegildo Zegna, Swarovski, MaxMara, Longchamp, and others. Alonso de Cordova also houses some of Santiago's most famous restaurants, art galleries, wine showrooms and furniture stores. The Costanera Center has stores like Armani Exchange, Banana Republic, Façonnable, Hugo Boss, Swarovski, and Zara. There are plans for a Saks Fifth Avenue in Santiago. Several mercados in the city such as the Mercado Central de Santiago sell local goods. Barrio Bellavista and Barrio Lastarria have some of the most exclusive night clubs, chic cafés and restaurants.

Transport

Air

Comodoro Arturo Merino Benítez International Airport (IATA: SCL) is Santiago's national and international airport and the principal hub of LATAM Airlines, Sky Airline, Aerocardal and JetSmart. The airport is located in the western commune of Pudahuel. The largest airport in Chile, it is ranked sixth in passenger traffic among Latin American airports, with 14,168,282 passengers served in 2012 – a 17% increase over 2011.[57] It is located 15 km from the city center.

Peldehue airport in Colina began operations on December 13, 2021. It will be able to service up to 25 flights per hour.[58] Santiago is also served by Eulogio Sánchez Airport (ICAO: SCTB), a small, privately owned general aviation airport in the commune of La Reina.

Rail

Trains operated by Chile's national railway company, Empresa de los Ferrocarriles del Estado (EFE), connect Santiago to several cities in the south-central part of the country: Rancagua, San Fernando, Talca (connected to the coastal city of Constitución by a different train service), Linares and Chillán. All such trains arrive and depart from the Estación Central railway station (Central Station), which can be accessed by bus or subway.[59] The proposed Santiago–Valparaíso railway line would connect Santiago with Valparaíso in 45 minutes, and expansions of the commuter rail network to Melipilla and Batuco are under discussion.

Inter-urban buses

Bus companies provide passenger transportation from Santiago to most areas of the country as well as to foreign destinations, while some also provide parcel shipping and delivery services.

There are several bus terminals in Santiago:

- Terminal San Borja: located in Metro station "Estación Central." Provides buses to all destinations in Chile and to some towns around Santiago.

- Terminal Alameda: located in Metro station "Universidad de Santiago." Provides buses to all destinations in Chile.

- Terminal Santiago: located one block west of Terminal Alameda. Provides buses to all destinations in Chile as well as to destinations in most countries in South America, except Bolivia.

- Terrapuerto Los Héroes: located two blocks east of Metro station "Los Héroes." Provides buses to south of Chile and some northern cities, as well as Argentina (Mendoza and Buenos Aires) and Paraguay (Asunción).

- Terminal Pajaritos: located in Metro station "Pajaritos." Provides buses to the international airport, inter-regional services to Valparaíso, Viña del Mar and several other coastal cities and towns.

- Terminal La Cisterna: located in Metro station "La Cisterna." Provides buses to towns around southern Santiago, Viña del Mar, Temuco and Puerto Montt.

- Terminal La Paz: located about two blocks away from the fresh fruit and vegetables market "Vega Central;" the closest Metro station is "Puente Cal y Canto." It connects the rural areas north of Santiago.

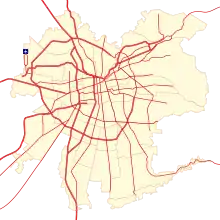

Highways

A network of free flow toll highways connects the various areas of the city. They include the Vespucio Norte and Vespucio Sur highways, which surround the city completing a nearly full circle; Autopista Central, the section of the Pan American highway crossing the city from north to south, divided in two highways 3 km (2 mi) apart; and the Costanera Norte, running next to the Mapocho River and connecting the international airport with the downtown and with the wealthier areas of the city to the east, where it divides into two highways.

Other non-free flow toll roads connecting Santiago to other cities, include: Rutas del Pacífico (Ruta 68), the continuation of the Alameda Libertador General Bernardo O'Higgins Avenue to the west, provides direct access to Valparaíso and Viña del Mar; Autopista del Sol (Ruta 78), connects Melipilla and the port of San Antonio with the capital; Autopista Ruta del Maipo (a.k.a. "Acceso Sur") is an alternative to the Pan American highway to access the various localities south of Santiago; Autopista Los Libertadores provides access to the main border crossing to Argentina, via Colina and Los Andes; and Autopista Nororiente, which provides access to the suburban development known as Chicureo, north of the capital.

Public transport

Santiago has 37% of Chile's vehicles, with a total of 991,838 vehicles, 979,346 of which are motorized. An extensive network of streets and avenues stretching across Santiago facilitate travel between the different communities that make up the metropolitan area.

In the 1990s the government attempted to reorganize the public transport system. New routes were introduced in 1994 and the buses were painted yellow. The system, however, had serious issues with routes overlapping, high levels of air and noise pollution, and safety problems for both riders and drivers. To tackle these issues a new transport system, called Transantiago, was devised. The system was launched in earnest on 10 February 2007, combining core services across the city with the subway and with local feeder routes, under a unified system of payment through a contactless smartcard called "Tarjeta bip!" The change was not well received by users, who complained of lack of buses, too many bus-to-bus transfers, and diminished coverage. Some of these problems were resolved, but the system earned a bad reputation which it has not been able to shake off. As of 2011, the fare evasion rate is stubbornly high.

In 2019, the government introduced the new public transport system named RED.

In recent years many cycle paths have been constructed, but so far the number is limited and with little connections between the routes. Most cyclists ride on the street, and the use of helmets and lights is not widespread, even though it is mandatory.

Metro

Santiago Metro has six operating lines (1, 2, 3, 4, 4A, 5 and 6), extending over 142 km (88 mi) and connecting 118 stations. The system carries around 2,400,000 passengers per day. Two underground lines (Line 4 and 4A) and an extension of Line 2 were inaugurated in 2005 and 2006, while an extension of Line 5 was inaugurated in 2011.[60][61] Line 6 was inaugurated in 2017, adding 10 stations to the network and approximately 15 km (9 mi) of track. Line 3 opened on January 22, 2019, with 18 new stations [62][61]

Commuter rail

EFE provides suburban rail service under the brandname of Metrotren. There are 2 southbound routes. The most popular is the Metrotren Nos service, between the Central Station of Santiago and Nos station, in San Bernardo. This line, inaugurated in 2017, serves 8 million people per year, with 12 trains serving 10 stations with a frequency of 6 minutes during rush hours, and 12 during the rest of the time. The other route is the Metrotren Rancagua service, between the Central Station of Santiago and the Rancagua station, connecting Santiago with the regional capital of O'Higgins.

Bus

Transantiago is the name for the city's public transport system. It works by combining local (feeder) bus lines and main bus lines, as well for the EFE commuter trains and the Metro network. It includes an integrated fare system, which allows passengers to make bus-to-bus, bus-to-metro or bus-to-train transfers for the price of one ticket, using a contactless smartcard (bip!). This system also offers reduced fares for the elderly, as well as high school and university students.

Vehicles for hire

Taxicabs are common in Santiago and are painted black with yellow roofs and have orange license plates. So-called radiotaxis may be called up by telephone and can be any make, model, or color but should always have the orange plates. Colectivos are shared taxicabs that carry passengers along a specific route for a fixed fee.

Public transportation statistics

The average amount of time people spend commuting with public transit in Santiago - to and from work, for example - on a weekday is 84 min. 23% of public transit riders ride for more than 2 hours every day. The average amount of time people wait at a stop or station for public transit is 15 min, while 21% of riders wait for over 20 minutes on average every day. The average distance people usually ride in a single trip with public transit is 7.4 km, while 15% travel for over 12 km in a single direction.[63]

Internal transport

As of 2006, Santiago was home to 992,000 vehicles, 979,000 of which were motorized. This made up 37.3% of Chile's total vehicle count. 805,000 cars passed through the city, which is 37.6% of the national total or one car for every seven people.[64]

The main road is the Avenida Libertador General Bernardo O'Higgins, better known as Alameda Avenue, which runs northeast and southwest. From north to south, it is crossed by Autopista Central and the Independencia, Gran Avenida, Recoleta, Santa Rosa, Vicuña Mackenna and Tobalaba avenues. Other major roads include the Avenida Los Pajaritos to the west and Providencia Avenue and Apoquindo Avenue to the east. Finally, the Américo Vespucio Avenue acts as a ring road.

During the 2000s, several urban highways were built through Santiago in order to improve the situation for vehicles. The road General Velásquez and sections of the Pan-American Highway in Santiago were converted into the Autopista Central, while Américo Vespucio became variously the highways Vespucio Norte Express and Vespucio Sur, as well as Vespucio Oriente in the future. Following the edge of the Mapocho River, Costanera Norte was built to link the northeast of the capital to the airport and the downtown area. All these highways, totaling 210 km in length, have a free flow toll system.

Administrative divisions

Greater Santiago lacks a metropolitan government for its administration, which is distributed between authorities, complicating the operation of the city as a single entity.[65] The highest authorities in Santiago are considered to be the governor of the Santiago Metropolitan Region, who is popularly elected to the office, now held by Claudio Orrego, and the regional presidential delegate of Santiago Metropolitan Region, an official appointed by the president of Chile, post currently occupied by Constanza Martínez.

The conurbation of Greater Santiago does not fit perfectly into any administrative division, as it extends into four different provinces and 35 communes plus 11 satellite communes which together make the Santiago Metropolitan Area. The majority of its 641.4 km2 (247.65 sq mi) (as of 2002)[66] lie within Santiago Province, with some peripheral areas contained in the provinces of Cordillera, Maipo, and Talagante.

Although there is no official consensus in this regard, the communes of the city are usually grouped into seven sectors: north, center, northeast, southeast, south, southeast and southwest.

.svg.png.webp)

| Communes of Santiago Province | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Communes in other provinces | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Culture

Only a few historical buildings from the Spanish colonial period remain in the city, because – like the rest of the country – Santiago is regularly hit by earthquakes. Extant buildings include the Casa Colorada (1769), the San Francisco Church (1586), and Posada del Corregidor (1750).

The cathedral on the central square (Plaza de Armas) is a sight that ranks as high as the Palacio de La Moneda, the Presidential Palace. The original building was built between 1784 and 1805, and architect Joaquín Toesca was in charge of its construction. Other buildings surrounding the Plaza de Armas are the Central Post Office Building, which was finished in 1882, and the Palacio de la Real Audiencia de Santiago, built between 1804 and 1807. It houses the Chilean National History Museum, with 12,000 objects that can be exhibited. On the southeast corner of the square stands the green cast-iron Commercial Edwards building, which was built in 1893. East of that is the colonial building of the Casa Colorada (1769), which houses the Museum of Santiago. Close by is the Municipal Theatre of Santiago, which was built in 1857 by the French architect Brunet of Edward Baines. It was badly damaged by an earthquake in 1906. Not far from the theater is the Subercaseaux Mansion and the National Library, one of the largest libraries of South America.

The Former National Congress Building, the Justice Palace, and the Royal Customs Palace (Palacio de la Real Aduana de Santiago) are located close to each other. The latter houses the Museum of pre-Columbian art. A fire destroyed the building of the Congress in 1895, which was then rebuilt in a neoclassical style and reopened in 1901. The Congress was deposed under the military dictatorship (1973–89) of Augusto Pinochet, and after the dictatorship was newly constituted on 11 March 1990, in Valparaíso.

The building of the Justice Palace (Palacio de Tribunales) is located on the south side of the Montt Square. It was designed by the architect Emilio Doyére and built between 1907 and 1926. The building is home to the Supreme Court of Chile. The panel of 21 judges is the highest judicial power in Chile. The building is also the headquarters of the Court of Appeals of Santiago.

Bandera street leads toward the building of the Santiago Stock Exchange (the Bolsa de Comercio), completed in 1917, the Club de la Unión (opened in 1925), the Universidad de Chile (1872), and toward the oldest churchhouse in the city, the San Francisco Church (constructed between 1586 and 1628), with its Marian statue of the Virgen del Socorro ("Our Lady of Help"), which was brought to Chile by Pedro de Valdivia. North of the Plaza de Armas ("Square of Arms," where the colonial militia was mustered) are the Paseo Puente, the Santo Domingo Church (1771), and the Central Market (Mercado Central), an ornamental iron building. Also in downtown Santiago is the Torre Entel, a 127.4-meter-high television tower with observation deck completed in 1974; the tower serves as a communication center for the communications company, ENTEL Chile.

The Costanera Center was completed in 2009, and includes housing, shopping, and entertainment venues. The project, with a total area of 600,000 square meters, includes the 300-meter high Gran Torre Santiago (South America's tallest building) and other commercial buildings. The four office towers are served by highway and subway connections.[67]

Municipal Theatre of Santiago

Municipal Theatre of Santiago Palacio de La Moneda

Palacio de La Moneda Contemporary Art Museum of Santiago

Contemporary Art Museum of Santiago Fine Arts Museum

Fine Arts Museum Biblioteca Nacional de Chile

Biblioteca Nacional de Chile Former Congress Building

Former Congress Building

Heritage and monuments

Within the metropolitan area of Santiago, there are 174 heritage sites in the custody of the National Monuments Council, among which are archeological, architectural and historical monuments, neighborhoods and typical areas. Of these, 93 are located within the commune of Santiago, considered the historic center of the city. Although no santiaguino monument has been declared a World Heritage Site by Unesco three have already been proposed by the Chilean government: the Incan sanctuary of El Plomo, the church and convent of San Francisco and the palace of La Moneda.

In the center of Santiago are several buildings built during the Spanish domination and that mostly correspond to, as the Metropolitan Cathedral and the aforementioned church of San Francisco Catholic churches. Buildings of the period are those located on the sides of Plaza de Armas, as the seat of Real Audiencia, the Post Office or the Casa Colorada.

During the nineteenth century and the advent of independence, new architectural works began to be erected in the capital of the young republic. The aristocracy built small palaces for residential use, mainly around the neighborhood Republica and preserved until today. To this other structures adopted artistic trends from Europe, as the Equestrian Club of Santiago, the head offices of the University of Chile and the Catholic University, Central Station and the Mapocho Station, Mercado Central, join the National Library, Museum of Fine Arts and the Barrio París-Londres, among others.

Various green areas in the city contain within and around various sites of heritage character. Among the most important are the fortifications of Santa Lucia hill, the shrine of the Virgin Mary on the summit of San Cristobal hill, the lavish crypt of the General Cemetery, Parque Forestal, the O'Higgins Park and the Quinta Normal Park.

Cultural activities and entertainment

In Santiago's major theater companies are located, hosting several national and international projects, with the highest expression during the International Theatre Festival known as Santiago a Mil, which takes place every January since 1994 and has gathered more than one million spectators. Also is the Planetarium at the University of Santiago de Chile.

To carry out various cultural, artistic and musical events, there are several precincts within which highlight the Mapocho Cultural Center, 100 Matucana Cultural Center, the Gabriela Mistral Cultural Center, Centro Cultural Palacio de La Moneda, the Movistar Arena and the Caupolican Theater. On the other hand, the opera and ballet performances are permanently accepted by the Municipal Theatre of Santiago, located in the heart of the city and which has a capacity of 1500 spectators.

There are 18 cinemas in the capital with a total of 144 rooms and over 32,000 seats, the projection centers than 5 arthouse add.

For children and teenagers, there are several entertainment venues, such as amusement park Fantasilandia, the National Zoo or the Buin Zoo on the outskirts of the city. The Bellavista, Brasil, Manuel Montt, Plaza Ñuñoa and Suecia account for most of the nightclubs, restaurants and bars in the city, the main evening entertainment centers in the capital. In order to promote the economic development of other regions, the law prohibits the construction of a casino in the metropolitan region, but nearby are the casino from the coastal city of Vina del Mar, 120 km from distance from Santiago, and Monticello Grand Casino in Mostazal, 56 kilometers south of Santiago, which opened in 2008.

Museums and libraries

Santiago has a wealth of museums of different kinds, among which are three of 'National' class administered by the Directorate of Libraries, Archives and Museums (DIBAM): the National History Museum, National Museum of Fine Arts and the National Museum of Natural History.

Most of the museums are located in the historic city center, occupying the old buildings of colonial origin, such as with the National History Museum, which is located in the Palacio de la Real Audiencia. La Casa Colorada houses the Museum of Santiago, while the Colonial Museum is housed in a wing of the Church of San Francisco and the Museum of Pre-Columbian Art occupies part of the old Palacio de la Aduana. The Museum of Fine Arts, though it is located in the city center, was built in the early twentieth century, especially for housing the museum and in the back of the building was laid in 1947, the Museum of Contemporary Art, under the Faculty of Arts of the University of Chile.

The Quinta Normal Park also has several museums, among which are the already mentioned of Natural History, Artequin Museum, the Museum of Science and Technology and the Museo Ferroviario. In other parts of the city there are some museums such as the Aeronautical Museum in Cerrillos, Museum of Tajamares in Providence and the Museo Interactivo Mirador in La Granja. The latter opened in 2000 and designed mainly for children and youth has been visited by more than 2.8 million visitors, making it the busiest museum in the country.

The most important public library is the National Library located in downtown Santiago. Its origins date back to 1813, when it was created by the nascent Republic and was moved to its current premises a century later, also home to the headquarters of the National Archives. In order to provide more closeness to the population, incorporating new technologies and complement the services provided by public libraries and the National Library was opened in 2005 the Library of Santiago at Barrio Matucana.

Music

Santiago has two symphony orchestras:

- Orquesta Filarmónica de Santiago ("Santiago Philharmonic Orchestra"), which performs in the Teatro Municipal (Municipal Theatre of Santiago)

- Orquesta Sinfónica de Chile ("Chile Symphony Orchestra"), part of the Universidad de Chile, performs in its theater.

There are a number of jazz establishments, some of them, including "El Perseguidor," "Thelonious," and "Le Fournil Jazz Club," are located in Bellavista, one of Santiago's "hippest" neighborhoods, though "Club de Jazz de Santiago," the oldest and most traditional one, is in Ñuñoa.[68] Annual festivals featured in Santiago include Lollapalooza and the Maquinaria festival.

Newspapers

The most widely circulated newspapers in Chile are published by El Mercurio and Copesa and have earned more than the 91% of revenues generated in printed advertizing in Chile.[69]

Some newspapers available in Santiago are:

- El Mercurio

- La Tercera

- La Cuarta

- Las Últimas Noticias

- La Segunda

- The Clinic

- The Santiago Times

Media

Santiago is home to the major Chilean television networks including the public broadcaster TVN and the privately held Canal 13, Chilevisión, La Red and Mega. In addition, the radio stations ADN Radio Chile, Radio Agricultura, Radio Concierto, Radio Cooperativa, Radio Pudahuel and Radio Rock & Pop are located in the city.

Sports

Santiago is home to some of Chile's most successful football clubs. Colo-Colo, founded on 19 April 1925, has a long tradition, and has played continuously in the highest league since the establishment of the first Chilean league in 1933. The club's wins include 30 national titles, 10 Copa Chile successes, and champions of the Copa Libertadores tournament in 1991, the only Chilean team to have won this tournament. The club hosts its home games in the Estadio Monumental in the commune of Macul.

Universidad de Chile has 18 national titles and 5 Copa Chile wins. In 2011 they were champions of Copa Sudamericana, the only Chilean team to have won this tournament. The club was founded on 24 May 1927, under the name Club Deportivo Universitario as a union of Club Náutico and Federación Universitaria. The founders were students of the University of Chile. In 1980, the organization separated from the University of Chile and the club is now completely independent. The team plays its home games in the Estadio Nacional de Chile in the commune of Ñuñoa.

Club Deportivo Universidad Católica (UC) was founded on 21 April 1937. It consists of fourteen different departments. This team plays its home games in Estadio San Carlos de Apoquindo. Universidad Católica has 13 national titles, making it the third most successful football club in the country. It has played the Copa Libertadores more than 20 times, reaching the final in 1993, losing to São Paulo FC.

Several other football clubs are based in Santiago, including Unión Española, Audax Italiano, Palestino, Santiago Morning, Magallanes and Barnechea. In addition to football, several sports are played in the city, tennis and basketball being the main ones. The Club Hípico de Santiago and the Hipódromo Chile are the two horseracing tracks in the city.

Santiago hosted the final stages of the official 1959 Basketball World Cup, where Chile won the bronze medal.

The city held a round of the all-electric FIA Formula E Championship on 3 February 2018, on a temporary street circuit incorporating the Plaza Baquedano and Parque Forestal.[70] It was the first FIA sanctioned race in the country.

The 2023 Pan American Games will be held in Santiago.[3]

Recreation

There is an extensive network of bicycle trails in the city, especially in the Providencia commune. The longest section is the Americo Vespuccio road, which contains a very wide dirt path with many trees through the center of a street used by motorists on both sides. The next longest path is along the Mapocho River along Andrés Bello Avenue. Many people use folding bicycles to commute to work.[71]

The city's main parks are:

- Cerro San Cristóbal – San Cristóbal Hill, which includes the Chilean National Zoo

- Parque O'Higgins – O'Higgins Park

- Parque Forestal – Forestal Park, park located at the city center alongside Mapocho river

- Cerro Santa Lucía – Santa Lucía Hill

- Parque Araucano in Las Condes adjacent to the Parque Arauco shopping mall contains 30 hectares of gardens. It is closed for maintenance on Mondays.

- Parque Inés de Suarez, Providencia

- Parque Padre Hurtado (a.k.a. Parque Intercomunal)

There are ski resorts to the east of the city (Valle Nevado, La Parva, El Colorado) and wineries in the plains west of the city.

Cultural venues include:

- Museo de Bellas Artes – Fine Arts Museum

- Museo Violeta Parra, an art museum dedicated to Chilean folk artist Violeta Parra [opened in 2015]

- Barrio Bellavista, cultural and bohemian neighborhood

- Central Station, railway station designed by Gustave Eiffel

- Víctor Jara Stadium

- Ex National Congress

- Plaza de Armas, central square

- Palacio de La Moneda, government palace

Santiago's Metropolitan Cathedral

Santiago's Metropolitan Cathedral - Teatro Municipal (Municipal Theatre of Santiago), the principal opera house of the country. The main sport venues are Estadio Nacional (site of the 1962 World Cup final), Estadio Monumental David Arellano, Estadio Santa Laura, and Estadio San Carlos de Apoquindo.

Religion

As in most of Chile, the majority of the population of Santiago is Catholic. According to the National Census, carried out in 2002 by the National Statistics Bureau (INE), in the Santiago Metropolitan Region, 3,129,249 people 15 and older identified themselves as Catholics, equivalent to 68.7% of the total population, while 595,173 (13.1%) described themselves as Evangelical Protestants. Around 1.2% of the population declared themselves as being Jehovah's Witnesses, while 2.0% identified themselves as Latter-day Saints (Mormons), 0.3% as Jewish, 0.1% as Eastern Orthodox and 0.1% as Muslim. Approximately 10.4% of the population of the Metropolitan Region stated that they were atheist or agnostic, while 5.4% declared that they followed other religions.[72] In 2010 construction was initiated on the Santiago Bahá'í Temple, serving as the Baháʼí House of Worship for South America, in the commune of Peñalolen.[73] Construction at the site was completed and the temple was dedicated in October 2016.[74]

Education

The city is home to numerous universities, colleges, research institutions, and libraries.

The largest university and one of the oldest in the Americas is Universidad de Chile. The roots of the university date back to the year 1622, as on 19 August the first university in Chile under the name of Santo Tomás de Aquino was founded. On 28 July 1738, it was named the Real Universidad de San Felipe in honor of King Philip V of Spain. In the vernacular, it is also known as Casa de Bello (Spanish: House of Bello – after their first Rector, Andrés Bello). On 17 April 1839, after Chile's independence from the Kingdom of Spain, it was renamed the Universidad de Chile, and reopened on 17 September 1843.[75]

The Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile (PUC) was founded in June 1888 and was ranked as the best school in Latin America in 2014.[76] On 11 February 1930 it was declared a university by a decree of Pope Pius XI. It received recognition by the Chilean government as an appointed Pontifical University in 1931. Joaquín Larraín Gandarillas (1822–1897), Archbishop of Anazarba, was the founder and first rector of the PUC. The PUC is a modern university; the campus of San Joaquin has a number of contemporary buildings and offers many parks and sports facilities. Several courses are conducted in English. Ex-president, Sebastián Piñera, minister Ricardo Raineri, and minister Hernán de Solminihac all attended PUC as students and worked in PUC as professors. In the 2010 admission process, approximately 48% of the students who achieved the best score in the Prueba de Selección Universitaria matriculated in the UC.[77]

Traditional

- Universidad de Chile (U or UCH)

- Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile (PUC)

- Universidad de Santiago de Chile (USACH)

- Universidad Metropolitana de Ciencias de la Educación (UMCE)

- Universidad Tecnológica Metropolitana (UTEM)

- Universidad Técnica Federico Santa María (UTFSM)

Non-traditional

- Universidad Adolfo Ibáñez (UAI)

- Universidad del Desarrollo (UDD)

- Universidad Diego Portales (UDP)

- Universidad Alberto Hurtado (UAH)

- Universidad Central de Chile (Ucen)

- Universidad Nacional Andrés Bello (Unab)

- Universidad Academia de Humanismo Cristiano (UAHC)

- Universidad Mayor (UM)

- Universidad Finis Terrae

- Universidad de Los Andes

- Universidad Gabriela Mistral (UGM)

- Universidad del Pacífico

- Universidad de las Américas

- Universidad de Artes, Ciencias y Comunicación (UNIACC)

- Universidad San Sebastián (USS)

- Universidad Bolivariana