Science fiction on television

Science fiction first appeared in television programming in the late 1930s, during what is called the Golden Age of Science Fiction. Special effects and other production techniques allow creators to present a living visual image of an imaginary world not limited by the constraints of reality.

|

| Speculative fiction |

|---|

|

|

Science fiction television production process and methods

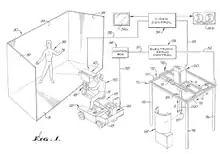

The need to portray imaginary settings or characters with properties and abilities beyond the reach of current reality obliges producers to make extensive use of specialized techniques of television production.

Through most of the 20th century, many of these techniques were expensive and involved a small number of dedicated craft practitioners, while the reusability of props, models, effects, or animation techniques made it easier to keep using them. The combination of high initial cost and lower maintenance cost pushed producers into building these techniques into the basic concept of a series, influencing all the artistic choices.

By the late 1990s, improved technology and more training and cross-training within the industry made all of these techniques easier to use, so that directors of individual episodes could make decisions to use one or more methods, so such artistic choices no longer needed to be baked into the series concept.

Special effects

Special effects (or "SPFX") have been an essential tool throughout the history of science fiction on television: small explosives to simulate the effects of various rayguns, squibs of blood and gruesome prosthetics to simulate the monsters and victims in horror series, and the wire-flying entrances and exits of George Reeves as Superman.

The broad term "special effects" includes all the techniques here, but more commonly there are two categories of effects. Visual effects ("VFX") involve photographic or digital manipulation of the onscreen image, usually done in post-production. Mechanical or physical effects involve props, pyrotechnics, and other physical methods used during principal photography itself. Some effects involved a combination of techniques; a ray gun might require a pyrotechnic during filming, and then an optical glowing line added to the film image in post-production. Stunts are another important category of physical effects. In general, all kinds of special effects must be carefully planned during pre-production.

Computer-generated imagery

Babylon 5 was the first series to use computer-generated imagery, or "CGI", for all exterior space scenes, even those with characters in space suits. The technology has made this more practical, so that today models are rarely used. In the 1990s, CGI required expensive processors and customized applications, but by the 2000s (decade), computing power has pushed capabilities down to personal laptops running a wide array of software.

Models and puppets

Models have been an essential tool in science fiction television since the beginning, when Buck Rogers took flight in spark-scattering spaceships wheeling across a matte backdrop sky. The original Star Trek required a staggering array of models; the USS Enterprise had to be built in several different scales for different needs. Models fell out of use in filming in the 1990s as CGI became more affordable and practical, but even today, designers sometimes construct scale models which are then digitized for use in animation software.

Models of characters are puppets. Gerry Anderson created a series of shows using puppets living in a universe of models and miniature sets, notably Thunderbirds. ALF depicted an alien living in a family, while Farscape included two puppets as regular characters. In Stargate SG-1, the Asgard characters are puppets in scenes where they are sitting, standing, or lying down. In Mystery Science Theater 3000, the characters of Crow T. Robot and Tom Servo, two of the show's main (and most iconic) characters, are puppets constructed from random household items.

Animation

As animation is completely free of the constraints of gravity, momentum, and physical reality, it is an ideal technique for science fiction and fantasy on television. In a sense, virtually all animated series allow characters and objects to perform in unrealistic ways, so they are almost all considered to fit within the broadest category of speculative fiction (in the context of awards, criticism, marketing, etc.) The artistic affinity of animation to comic books has led to a large amount of superhero-themed animation, much of this adapted from comics series, while the impossible characters and settings allowed in animation made this a preferred medium for both fantasy and for series aimed at young audiences.

Originally, animation was all hand-drawn by artists, though in the 1980s, beginning with Captain Power, computers began to automate the task of creating repeated images; by the 1990s, hand-drawn animation became defunct.

Animation in live-action

In recent years as technology has improved, this has become more common, notably since the development of the Massive software application permits producers to include hordes of non-human characters to storm a city or space station. The robotic Cylons in the new version of Battlestar Galactica are usually animated characters, while the Asgard in Stargate SG-1 are animated when they are shown walking around or more than one is on screen at once.

Science fiction television economics and distribution

In general, science fiction series are subject to the same financial constraints as other television shows. However, high production costs increase the financial risk, while limited audiences further complicate the business case for continuing production. Star Trek was the first television series to cost more than $100,000 per episode, while Star Trek: The Next Generation was the first to cost more than $1 million per episode.

The innovative nature of science fiction means that new shows cannot rely on predictable market-tested formulas like legal dramas or sitcoms; the involvement of creative talent outside the Hollywood mainstream introduces more variables to the budget forecasts.

In the past, science fiction television shows have maintained a family friendly format that rendered them suitable for all ages, especially children, as the majority of them were of the action-adventure format. This enabled merchandising such as toy lines, animated cartoon adaptations, and other licensing. However, many modern shows include a significant amount of adult themes (such as sexual situations, nudity, profanity and graphic violence) rendering them unsuitable for young audiences, and severely limiting the remaining audience demographic and the potential for merchandising.

The perception, more than the reality, of science fiction series being cancelled unreasonably is greatly increased by the attachment of fans to their favorite series, which is much stronger in science fiction fandom than it is in the general population. While mainstream shows are often more strictly episodic, where ending shows can allow viewers to imagine that characters live happily, or at least normally, ever after, science fiction series generate questions and loose ends that, when unresolved, cause dissatisfaction among devoted viewers. Creative settings also often call for broader story arcs than is often found in mainstream television, requiring science fiction series many episodes to resolve an ongoing major conflict. Science fiction television producers will sometimes end a season with a dramatic cliffhanger episode to attract viewer interest, but the short-term effect rarely influences financial partners. Dark Angel is one of many shows ending with a cliffhanger scene that left critical questions open when the series was cancelled.

Media fandom

One of the earliest forms of media fandom was Star Trek fandom. Fans of the series became known to each other through the science fiction fandom. In 1968, NBC decided to cancel Star Trek. Bjo Trimble wrote letters to contacts in the National Fantasy Fan Foundation, asking people to organize their local friends to write to the network to demand the show remain on the air. Network executives were overwhelmed by an unprecedented wave of correspondence, and they kept the show on the air. Although the series continued to receive low ratings and was canceled a year later, the enduring popularity of the series resulted in Paramount creating a set of movies, and then a new series Star Trek: The Next Generation, which by the early 1990s had become one of the most popular dramas on American television.

Star Trek fans continued to grow in number, and first began organizing conventions in the 1970s. No other show attracted a large organized following until the 1990s, when Babylon 5 attracted both Star Trek fans and a large number of literary SF fans who previously had not been involved in media fandom. Other series began to attract a growing number of followers. The British series, Doctor Who, has similarly attracted a devoted following.

In the late 1990s, a market for celebrity autographs emerged on eBay, which created a new source of income for actors, who began to charge money for autographs that they had previously been doing for free. This became significant enough that lesser-known actors would come to conventions without requesting any appearance fee, simply to be allowed to sell their own autographs (commonly on publicity photos). Today most events with actor appearances are organized by commercial promoters, though a number of fan-run conventions still exist, such as Toronto Trek and Shore Leave.

The 1985 series Robotech is most often credited as the catalyst for the Western interest in anime. The series inspired a few fanzines such as Protoculture Addicts and Animag both of which in turn promoted interest in the wide world of anime in general. Anime's first notable appearance at SF or comic book conventions was in the form of video showings of popular anime, untranslated and often low quality VHS bootlegs. Starting in the 1990s, anime fans began organizing conventions. These quickly grew to sizes much larger than other science fiction and media conventions in the same communities; many cities now have anime conventions attracting five to ten thousand attendees. Many anime conventions are a hybrid between non-profit and commercial events, with volunteer organizers handling large revenue streams and dealing with commercial suppliers and professional marketing campaigns.

For decades, the majority of science fiction media fandom has been represented by males of all ages and for most of its modern existence, a fairly diverse racial demographic. The most highly publicized demographic for science fiction fans is the male adolescent; roughly the same demographic for American comic books. Female fans, while always present, were far fewer in number and less conspicuously present in fandom. With the rising popularity of fanzines, female fans became increasingly vocal. Starting in the 2000s (decade), genre series began to offer more prominent female characters. Many series featured women as the main characters with males as supporting characters. True Blood is an example. Also, such shows premises moved away from heroic action-adventure and focused more on characters and their relationships. This has caused the rising popularity of fanfiction, a large majority of which is categorized as slash fanfiction. Female fans comprise the majority of fanfiction writers.

Science fiction television history and culture

U.S. television science fiction

U.S. television science fiction has produced Lost In Space, Star Trek, The Twilight Zone, and The X-Files, among others.

British television science fiction

British television science fiction began in 1938 when the broadcast medium was in its infancy with the transmission of a partial adaptation of Karel Čapek's play R.U.R.. Despite an occasionally chequered history, programmes in the genre have been produced by both the BBC and the largest commercial channel, ITV. Doctor Who is listed in the Guinness World Records as the longest-running science fiction television show in the world[2] and as the "most successful" science fiction series of all time.[3]

Other British cult series are Space: 1999 and Red Dwarf.

Canadian science fiction television

Science fiction in Canada was produced by the CBC as early as the 1950s. In the 1970s, CTV produced The Starlost. In the 1980s, Canadian animation studios including Nelvana, began producing a growing proportion of the world market in animation.

In the 1990s, Canada became an important player in live action speculative fiction on television, with dozens of series like Forever Knight, Robocop, and most notably The X-Files and Stargate SG-1. Many series have been produced for youth and children's markets, including Deepwater Black and MythQuest.

In the first decade of the 21st century, changes in provincial tax legislation prompted many production companies to move from Toronto to Vancouver. Recent popular series produced in Vancouver include The Dead Zone, Smallville, Andromeda, Stargate Atlantis, Stargate Universe, The 4400, Sanctuary and the reimagined Battlestar Galactica.

Because of the small size of the domestic television market, most Canadian productions involve partnerships with production studios based in the United States and Europe. However, in recent years, new partnership arrangements are allowing Canadian investors a growing share of control of projects produced in Canada and elsewhere.

Australian science fiction television

Australia's first locally produced Science Fiction series was The Stranger (1964–65) produced and screened by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation . Later series made in the 1960s included The Interparis (1968) Vega 4 (1967), and Phoenix Five (1970). The country's best known Science Fiction series was Farscape; an American co-production, it ran from 1999 to 2003. A significant proportion of Australian produced Science Fiction programmes are made for the teens/young Adults market, including The Girl from Tomorrow, the long-running Mr. Squiggle, Halfway Across the Galaxy and Turn Left, Ocean Girl, Crash Zone, Watch This Space and Spellbinder.

Other series like Time Trax, Roar, and Space: Above and Beyond were filmed in Australia, but used mostly US crew and actors.[4]

Japanese television science fiction

Japan has a long history of producing science fiction series for television. Some of the most famous are anime such as Osamu Tezuka's Astro Boy, the Super Robots such as Mitsuteru Yokoyama's Tetsujin 28-go (Gigantor) and Go Nagai's Mazinger Z, and the Real Robots such as Yoshiyuki Tomino's Gundam series and Shōji Kawamori's Macross series.

Other primary aspects of Japanese science fiction television are the superhero tokusatsu (a term literally meaning special effects) series, pioneered by programs such as Moonlight Mask and Planet Prince. The suitmation technique has been used in long running franchises include Eiji Tsuburaya's Ultra Series, Shotaro Ishinomori's Kamen Rider Series, and the Super Sentai Series.

In addition, several dramas utilize science fiction elements as framing devices, but are not labeled as "tokusatsu" as they do not utilize actors in full body suits and other special effects.

German series

Among the notable German language productions are:

- Raumpatrouille, a German series first broadcast in 1966,

- The miniseries Das Blaue Palais by Rainer Erler,

- Star Maidens (1975, aka "Medusa" or "Die Mädchen aus dem Weltraum") was a British-German coproduction of pure SF.

- Der Androjäger (1982/83) was a sci-fi comedy produced by Bavaraia Filmstudios in cooperation with Norddeutscher Rundfunk.

- Lexx, a German-Canadian co-production from 2000.

Danish series

Danish television broadcast the children's TV-series Crash in 1984 about a boy who finds out that his room is a space ship.

Dutch series

Early Dutch television series were Morgen gebeurt het (Tomorrow it will happen), broadcast from 1957 to 1959, about a group of Dutch space explorers and their adventures, De duivelsgrot (The devil's cave), broadcast from 1963 to 1964, about a scientist who finds the map of a cave that leads to the center of the earth and Treinreis naar de Toekomst (Train journey to the future) about two young children who are taken to the future by robots who try to recreate humanity, but are unable to give the cloned humans a soul. All three of these television series were aimed mostly at children.

Later television series were Professor Vreemdeling (1977) about a strange professor who wants to make plants speak and Zeeuws Meisje (1997) a nationalistic post-apocalyptic series where the Netherlands has been built full of housing and the highways are filled with traffic jams. The protagonist, a female superhero, wears traditional folkloric clothes and tries to save traditional elements of Dutch society against the factory owners.

Italian series

Italian TV shows include A come Andromeda (1972) which was a remake of 1962 BBC serial, A for Andromeda (from the novels of Hoyle and Elliott), Geminus (1968), Il segno del comando (1971), Gamma (1974) and La traccia verde (1975).

French series

French series are Highlander: The Series, French science-fiction/fantasy television series (both co-produced with Canada) and a number of smaller fiction/fantasy television series, including Tang in 1971, about a secret organization that attempts to control the world with a new super weapon, "Les atomistes" and 1970 miniseries "La brigade des maléfices".

Another French-produced science fiction series was the new age animated series Il était une fois... l'espace (English: Once upon a time...space). Anime-influenced animation includes a series of French-Japanese cartoons/anime, including such titles as Ulysses 31 (1981), The Mysterious Cities of Gold (1982), and Ōban Star-Racers (2006).

Spanish series

The first Spanish SF series was Diego Valor, a 22 episode TV adaption of a radio show hero of the same name based on Dan Dare, aired weekly between 1958 and 1959. Nothing was survived of this series, not a single still; it is not known if the show was even recorded or just a live broadcast.[5][6][7]

The 60s were dominated by Chicho Ibáñez Serrador and Narciso Ibáñez Menta, who adapted SF works from Golden Age authors and others to a series titled Mañana puede ser verdad. Only 11 episodes were filmed. The 70s saw three important television films, Los pajaritos (1974), La Gioconda está triste (1977), and La cabina (1972), this last one, about a man who becomes trapped in a telephone booth, while passersby seem unable to help him, won the 1973 International Emmy Award for Fiction.[8]

The series Plutón B.R.B. Nero (2008) was a brutal SF comedy by Álex de la Iglesia, in the line of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, Red Dwarf, or Doctor Who, with 26 episodes of 35 minutes.[9][10][11] Other series of the 2010s were Los protegidos (2010-2012), El barco (2011-2013), and El internado (2007-2010), all three inspired by North American productions, with minor SF elements.[12][13]

The latest success is El ministerio del tiempo (The ministry of time), premiered on February 24, 2015 on TVE's main channel La 1. The series follows the exploits of a patrol of the fictional Ministry of Time, which deals with incidents caused by time travel.[14][15][16] It has garnered several national prizes in 2015, like the Ondas Prize, and has a thick following on-line, called los ministéricos.[17][18]

Eastern European series

Serbia produced The Collector (Sakupljač), a science fiction television series based upon Zoran Živković's story, winner of a World Fantasy Award.

Návštěvníci (The Visitors) was a Czechoslovak (and Federal German, Swiss and French) TV series produced in 1981 to 1983. The family show aired in a larger number of European countries.

Significant creative influences

For a list of notable science fiction series and programs on television, see: List of science fiction television programs.

People who have influenced science fiction on television include:

- Irwin Allen, creator of Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, The Time Tunnel, Lost in Space and Land of the Giants

- Gerry Anderson, creator of Supercar, Fireball XL5, Stingray, Thunderbirds, Captain Scarlet and the Mysterons, Joe 90, UFO, Space: 1999, Terrahawks, Space Precinct and New Captain Scarlet.

- Joseph Barbera and William Hanna, animators and producers of The Jetsons, Jonny Quest, Valley of the Dinosaurs, Mightor, and Samson & Goliath

- Chris Carter, creator of The X-Files, The Lone Gunmen, Harsh Realm, and Millennium

- Russell T Davies, revived the Doctor Who franchise and created its spinoffs Torchwood and The Sarah Jane Adventures

- Kenneth Johnson, producer and director of The Six Million Dollar Man, The Bionic Woman, The Incredible Hulk, V (also creator), and Alien Nation

- Sid & Marty Krofft, producers and creators of Land of the Lost and its 1991 remake, The Lost Saucer, Far Out Space Nuts, and Electra Woman and Dyna Girl

- Nigel Kneale, writer and creator of the Quatermass serials

- Glen A. Larson, creator of Battlestar Galactica, Buck Rogers in the 25th Century, Galactica 1980 and Knight Rider

- Carl Macek, producer of the 1985 American anime series Robotech (based on adaptations of 3 separate Japanese animated series). Also producer of Captain Harlock and the Queen of a Thousand Years.

- Ronald D. Moore, creator of the re-imagined Battlestar Galactica; producer and writer for Star Trek: The Next Generation, Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, and Roswell

- Terry Nation, creator of the Daleks in Doctor Who, and of his own shows Survivors and Blake's 7

- Sydney Newman, creator of Doctor Who, The Avengers, and other telefantasy series

- Rockne S. O'Bannon, creator of Alien Nation, seaQuest DSV, and Farscape.

- Gene Roddenberry, the creator of Star Trek, Star Trek: The Next Generation, Earth: Final Conflict, and Andromeda

- Rod Serling, creator of The Twilight Zone and Night Gallery.

- Leslie Stevens and Joseph Stefano, creators of The Outer Limits.

- J. Michael Straczynski, creator of Babylon 5, Crusade, Jeremiah, and Sense8.

- Joss Whedon, creator of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Angel, Firefly, and Dollhouse.

- Robert Hewitt Wolfe, writer, producer, and/or executive producer of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, Andromeda, The Dead Zone, The 4400, and The Dresden Files.

- Brad Wright, writer, producer, co-creator and/or executive producer of Stargate SG-1, Stargate Atlantis, and Stargate Universe[19]

See also

- Cultural influence of Star Trek

- Fantasy television

- List of Sci Fi Pictures original movies

- List of science fiction sitcoms

- List of science fiction television films

- List of Star Wars television series

- Science fiction film

- Science fiction television series

References

- Mark Phillips; Frank Garcia. Science Fiction Television Series. McFarland.

- "Dr Who 'longest-running sci-fi'". BBC News. 28 September 2006. Retrieved 30 September 2006.

- Miller, Liz Shannon (26 July 2009). "Doctor Who Honored by Guinness — Entertainment News, TV News, Media". Variety. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

- Post, Jonathan Vos. "TV page of ULTIMATE SCIENCE FICTION WEB GUIDE". www.magicdragon.com.

- Jiménez, Jesús (23 August 2013). "Andreu Martín y Enrique Ventura resucitan a 'Diego Valor'". rtve (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- Boix, Armando (5 June 1999). "La aventura interplanetaria de Diego Valor". Ciencia-ficción.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- Agudo, Angel (July 2006). "Diego Valor: Una aventura en España y el Espacio". Fuera de Series (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- Jiménez, Jesús (18 February 2012). "La ciencia ficción, un género tan raro en el cine español como estimulante". rtve (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- "Álex de la Iglesia inicia su viaje espacial en Televisión Española". Vertele (in Spanish). 16 July 2008. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- Bartolomé, Eva Mª (17 July 2008). "Si España tuviera que salvar al mundo". El Mundo (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- Vidiella, Rafa (24 September 2008). "Álex de la Iglesia se estrena en televisión con su serie 'Plutón BRB Nero'". 20 Minutos (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- Puebla Martínez, Belén; Carrillo Pascual, Elena; Iñigo Jurado, Ana Isabel. "Las tendencias de las series de ficción españolas en los primeros años del siglo XXI". Lecciones del portal (in Spanish). ISSN 2014-0576. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- Alabadí Lunes, Héctor (15 February 2016). "5 veces que las series españolas lo intentaron con la ciencia ficción y la fantasía, y fallaron". e-cartelera (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- Monegal, Ferran (26 February 2015). "Un ministro secreto y oculto". El Periódico (in Spanish). Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- Rey, Alberto (24 February 2015). "El Ministerio del tiempo: un viaje sin complejos". El Mundo (in Spanish). Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- Marín Bellón, Federico (25 February 2015). ""El Ministerio del Tiempo": el futuro de la ficción española". ABC (in Spanish). Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- "'El Ministerio del Tiempo' se estrena el martes 24 de febrero contra 'Bajo sospecha'". FormulaTV (in Spanish). 18 February 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- González, Daniel (6 April 2015). "Los fans convierten la serie 'El Ministerio del Tiempo' en un fenómeno sin precedentes". 20 minutos (in Spanish). Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- Malcom, Nollinger, Rudolph, Tomashoff, Weeks, & Williams (2004-08-01). "25 Greatest Sci-Fi Legends". TV Guide: 31–39.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)