Self-fulfilling prophecy

A self-fulfilling prophecy is the psychological phenomenon of someone "predicting" or expecting something, and subsequently the person's resulting behaviors align to fulfill the belief, and as such this "prediction" or expectation coming true simply because the person believes or anticipates it will.[1] This suggests that people's beliefs influence their actions. The principle behind this phenomenon is that people create consequences regarding people or events, based on previous knowledge of the subject.

There are three factors within an environment that can come together to influence the likelihood of a self-fulfilling prophecy becoming a reality: appearance, perception and belief.[2] When a phenomenon cannot be seen, appearance is what we rely upon when a self-fulfilling prophecy is in place.[2] When it comes to a self-fulfilling prophecy there also must be a distinction "between 'brute and institutional' facts".[3] The philosopher John Searle states the difference as "facts [that] exist independently of any human institutions; institutional facts can only exist within institutions." There is an inability of institutional facts to be self-fulfilling. For example, the old belief that the Earth is flat (institutional) when it is known to be spherical (brute) is not self-fulfilling, because Earth's shape is proven through significant evidence. There has to be a consensus by "large numbers of people within a given population"[2]—aside from being institutional, social, or bound by the laws of nature for an idea—to be seen as self-fulfilling.

A self-fulfilling prophecy can have either negative or positive outcomes. It can be concluded that establishing a label towards someone or something significantly impacts their perception and influences them to establish self-fulfilling prophecy.[4] Interpersonal communication plays a significant role in establishing these phenomena as well as impacting the labeling process. Intrapersonal communication can have both positive and negative effects, dependent on the nature of the self-fulfilling prophecy. The expectations of a relationship or the inferiority complex felt by young minority children are examples of the negative effects of real false beliefs being self-fulfilling.[5]

American sociologists W. I. Thomas and Dorothy Swaine Thomas were the first Western scholars to investigate this phenomenon. In 1928 they developed the Thomas theorem (also known as the Thomas dictum), stating that, "If men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences."[6] Because of the way the couple defined a self-fulfilling prophecy, their definition was regarded as flexible in its meaning. On a societal level, there can be a consensus on what's deemed true depending on the importance of the part of the culture even if it is a false assumption and as a result of this perception of the culture it will become the outcome based on the behavior of the society. A person's perception can be "self-creating" if the belief they have is acted upon by their behavior which aligns with the outcome. Building on Thomas' idea, another American sociologist, Robert K. Merton, used the term "self-fulfilling prophecy" for it, popularizing the idea that "a belief or expectation, correct or incorrect, could bring about a desired or expected outcome."[1][7] While Robert K. Merton is typically credited for this theory because he coined the name; however, the Thomases developed it earlier on—along with the philosophers Karl Popper and Alan Gerwith—who also independently contributed to the idea behind this theory in their works, which also came before Merton. Self-fulfilling prophecies are an example of the more general phenomenon of positive feedback loops.

History

Robert K. Merton was a sociologist who helped to further develop many different theories such as anomie, social structure as well as the different modes of individual adaption.[8] Merton was deeply passionate and interested in the sociology of science, during his time at Columbia University he was able to research and discover many different concepts such as "social structure, bureaucracy, mass communication, and the sociology of science".[8] He established what his theory was and he would then start testing it right away without developing the concept. Merton would not worry about developing the theory because he was never looking for a "grand" theory, he was looking for a "practical" theory.[8]

Merton applied this concept to a fictional situation called "The Last National Bank".[9] In his book Social Theory and Social Structure, he uses the example of a bank run to show how self-fulfilling thoughts can make unwanted situations happen. Rumors spread around the town about the Millingville bank and Merton mentions how a number of people falsely believe the bank was going to file for bankruptcy. Because of this false fear, many people decide to go to the bank and ask for all of their cash at once. The owner of the bank, Cartwright Millingville was once proud about the bank being alive and well which was thanks to the ubiquitous trust in the bank which gave it its stability but as the week fell upon what was called "Black Wednesday", things took a turn when the depositors lost faith in the validity of the bank according to Merton. These actions cause the bank to indeed go bankrupt because banks rarely have the amount of cash on hand to satisfy a large number of customers asking for all of their deposited cash at once. The people with money in the bank were the ones to define their perception or truth of the bank's ability to safely hold their money without risk. They were able to determine their new definition of the bank which became an overall consensus as many rushed to withdraw whatever was left after their scramble to ensure their money was secure in their own hands. Their loss of faith led to the bank's eventual failure which was not an initially true assumption until the depositors made it so.

Merton concludes this example with the analysis, "The prophecy of collapse led to its own fulfillment".[10]

While Merton's example focused on self-fulfilling prophecies within a business, his theory is also applicable to interpersonal communication, since it is found to have a "potential for triggering self-fulfilling prophecy effects".[11] This is due to the fact "that an individual decides whether or not to conform to the expectations of others".[11] This makes people rely upon or fall into self-fulfilling thoughts, since they are trying to satisfy other's perceptions of them. This theory was applied to experiments done by Dr. Robert Rosenthal and Lenore Jacobson in the Pygmalion in the Classroom Study who tested the IQ's of 1st and 2nd grade elementary students. Where random students' IQ scores aligned with the expectation the teachers had been given about the students eventual success.[5]

Self-fulfilling theory can be divided into two behaviors, one would be the Pygmalion effect which is when "one person has expectations of another, changes her behavior in accordance with these expectations, and the object of the expectations then also changes her behavior as a result".[11]

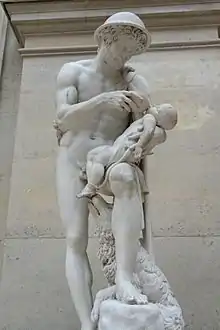

Additionally, philosopher Karl Popper called the self-fulfilling prophecy the Oedipus effect:

One of the ideas I had discussed in The Poverty of Historicism was the influence of a prediction upon the event predicted. I had called this the "Oedipus effect", because the oracle played a most important role in the sequence of events which led to the fulfilment of its prophecy. [...] For a time I thought that the existence of the Oedipus effect distinguished the social from the natural sciences. But in biology, too—even in molecular biology—expectations often play a role in bringing about what has been expected.[12]

An early precursor of the concept appears in Edward Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire: "During many ages, the prediction, as it is usual, contributed to its own accomplishment" (chapter I, part II).

Applications

Examples abound in studies of cognitive dissonance theory and the related self-perception theory; people will often change their attitudes to come into line with what they profess publicly.[13]

Teacher expectations influence student academic performance.[14][15]: 114 In the United States, the concept was broadly and consistently applied in the field of public education reform, following the "War on Poverty". Theodore Brameld noted: "In simplest terms, education already projects and thereby reinforces whatever habits of personal and cultural life are considered to be acceptable and dominant."[16] The effects of teacher attitudes, beliefs and values, affecting their expectations have been tested repeatedly.[17] Students may study more if they had a positive experience with their teacher.[15]: 115 Or female students may perform worse if they expected their male instructor is a sexist.[18]

The phenomenon of the "inevitability of war" is a self-fulfilling prophecy that has received considerable study.[19]

Fear of failure leads to deterioration of results, even if the person is objectively able to adequately cope with the problem. For example, fear of falling leads to more falls among older people.[20]

Americans of Chinese and Japanese origin are more likely to die of a heart attack on the 4th of each month.[21] This is because number 4 is "unlucky" in these cultures. The pronunciation of "4" and "death" is very similar in Chinese.[22]

The idea is similar to that discussed by the philosopher William James as "The Will to Believe." But James viewed it positively, as the self-validation of a belief. Just as, in Merton's example, the belief that a bank is insolvent may help create the fact, so too, on the positive side, confidence in the bank's prospects may help brighten them. Similarly, Stock-exchange panic episodes, and speculative bubble episodes, can be triggered with the belief that the stock will go down (or up), thus starting the selling/buying mass move, etc.

A more Jamesian example: a swain, convinced that the fair maiden must love him, may prove more effective in his wooing than he would had his initial prophecy been defeatist.

There is extensive evidence of "Interpersonal Expectation Effects", where the seemingly private expectations of individuals can predict the outcome of the world around them. The mechanisms by which this occurs are also reasonably well understood: it is simply that our own expectations change our behaviour in ways we may not notice and correct. In the case of the "Interpersonal Expectation Effects", others pick up on non-verbal behaviour, which affects their attitudes. An example includes the Pygmalion in the Classroom study where teachers were told arbitrarily that random students were likely to show significant intellectual growth[2] As a result, those random students actually ended the year with significantly greater improvement when given another IQ test "The control group for all grade levels gained about eight points between the two tests, while the treatment group gained about twelve;"[2] Although the exact actions behind what the teachers did to lead the study towards the initial expectation of student success is unknown, teachers who have higher expectations typically, give "more time to answer questions, more specific feedback, and more approval".[23]

A classic experiment was conducted by Robert Rosenthal and Lenore Jacobson in American elementary schools in 1968.[24] Using a simulation test, he convinced the staff that some of the students he chose at random were intellectually gifted and would show excellent results in the future. When measuring intelligence at the end of the school year, 45 percent of children selected as "high-grade" showed an increase in their IQ of 20 or more, with some children showing an improvement of 30 points.[25][26][27]

People adapt to the judgments and assessments made by society, regardless of whether they were originally correct or not. There are certain prejudices against a socially marginalized group (e.g. homeless people, drug addicts or other minorities), and therefore people in this marginalized group actually begin to behave in accordance with expectations.[28] If the behavior is influenced solely by the expectations of a particular person in power (e.g., a leader, teacher, doctor, or researcher), then we are talking about the Pygmalion effect.

Relationships

A leading study by Columbia University found that self-fulfilling prophecies have some part in relationships. The beliefs by people in relationships can impact the likelihood of a breakup or the overall health of the relationship. It was suggested by L. Alan Sroufe, that "rejection expectations can lead people to behave in ways that elicit rejection from others."[29] The study looked at the inner workings behind the role of self-fulfilling prophecies in romantic relationships of people who were deemed high in rejection sensitivity which was defined as "the disposition to anxiously expect, readily perceive, and overreact to rejection". Couples were sampled from Columbia University and prompted to journal their thoughts and feelings in regards to their relationships. The psychologist professor Dr. Geraldine Downey found that women were more likely to experience rejection sensitivity in comparison to the negativity held by men about the future of their relationships. "RS was a stronger predictor of concern about rejection during conflict, and of feeling lonely and unloved after conflict, in women than in men" The original hypothesis aligned with the findings that "HRS women may be more likely to behave in ways that exacerbate conflicts." The conclusion was that women with high rejection sensitivity were more likely to "behave in ways that erode their partners' relationship satisfaction and commitment."[29] The feelings of rejection would eventually cause the women to stop the relationship from the built up dissatisfaction.

Other specific examples discussed in psychology include:

- "Clever Hans" effect

- Observer-expectancy effect

- Hawthorne effect

- Placebo effect

- Nocebo effect

- Pygmalion effect

- Stereotype threat

International relations applications

Self-fulfilling prophecies have been apparent throughout history where different countries fall into the 'Thucydides trap'. This term has been coined by Graham Allison and is defined by the occurrence of a rising power threatening a ruling or dominant power.[30] Thuycidides was an Athenian historian and general who recorded the Peloponnesian war between Sparta and Athens. Thuycidides wrote, ""It was the rise of Athens and the fear that this instilled in Sparta that made war inevitable." The common theme of feeling threatened by another worldly power that may eventually surpass them puts the dominant power in a position to act on its fears which would equate to a potential war.

A present day example of this sense of worry and anxiety is of China's rapid progression which threatens the U.S. as a dominant or ruling power.[31] If the United States were to let the continuous growth of China lead into competition and the behavior of trying to restrict the growth of China it would push the two powers towards war which would be the result of the self-fulling prophecy. American political scientist Joseph Nye Jr. suggests to security analysts not to be too hasty as to allow their fear of impending conflict to become a reality and cause a self-fulfilling prophecy to occur. If countries make others out to be an enemy in their head, they secure the future of hostility.

Another example of self-fulfilling prophecies is when the U.S. invaded Iraq back in 2002 based on the assumption it was a terrorist threat.[31] However, according to evidence, it shows that no threat was posed by Iraq.[32][33][34] The decisions made by the Bush administration stemmed from the desire to overthrow and dominate the regime which resulted in Iraq becoming a terrorist threat and a stronghold for the terrorist organization known as Al Qaeda., and henceforth confirming the initial belief of a potential threat. The belief that democratic peace is the best way to maintain a country is only deemed true among the masses falls into the category of being a self-fulfilling prophecy. If one country perceives another as peaceful and not restricting their ability to grow and function as they currently do, the belief will be held by both. This makes the definition when applied to countries as flexible for the possibility that it can also depend on the consensus of those who believe in a specific principle.

Stereotype

Self-fulfilling prophecies are one of the main contributions to racial prejudice and vice versa. According to the Dictionary of Race, Ethnicity & Culture "Self-fulfilling prophecy makes it possible to highlight the tragic vicious circle which victimizes people twice: first, because the victim is stigmatized (STIGMA) with an inherent negative quality; and secondly, because he or she is prevented from disproving this quality."[35] To prove this, the author uses the example that Merton used in his book about how white workers expected that black people would be against the principles of trade unionism because white workers considered black workers to be "undisciplined in traditions of trade unionism and the art of collective bargain-ing."[36] This prediction caused the event to happen (black workers would be against trade unionism), because this forecast became fact when all white people started to believe this and did not let the black workers get a job at any white men's business. This made black workers unable to learn or approve the principles of trade unionism, since they were not given the chance of working in a work environment where these principles were seen or experienced.

In the article "The Accumulation of Stereotype-based self-fulfilling Prophecies." The authors mention how teachers can encourage stereotype-based courses and can interact with students in a manner that encourages self-fulfilling thoughts. The example that was given was the one of a female student who seemed to do bad in math and her math teacher and counselor "channel her in the direction of confirming sex stereotypes"[37] By this the author means that the teachers never encouraged her to improve her abilities in math. Instead, the teacher and the counselor recommended classes that were dominated by females.

African American psychologist Kenneth B. Clark studied the responses of Black children ages 3–7 years old to black and white dolls in the 1960s. From his reports on his research, the term "self-fulfilling prophecy" made its first appearance in educational literature.[5] The theory of self-fulfilling prophecy contributed to the impact of racism on the children. The responses from Clark's study ranged from some calling the black doll ugly and one girl bursting into tears when prompted to pick the doll she identified with. The black children internalized the inferiority they learned and acted as such as a result of their placement within society. Clark who aided in pushing the Supreme court decision towards the desegregation of schools in the case of the Brown v. The Board of Education, also noted the influence of teachers on the achievement levels between black and white students. ""the importance of the role of teachers in developing self-image, academic aspirations and achievements of their students"" prompted Clark to begin a study in 10 inner-city schools where he assessed the attitudes and behaviors of teachers. The belief held by teachers was that minority students were dumb and therefore they didn't put effort into them. The low expectations of the teachers aligned with their initial belief which was low IQ test scores.

Clark wrote, ""If a child scores low on an intelligence test because he cannot read and then is not taught to read because he has a low score, then such a child is being imprisoned in an iron circle and becomes the victim of an educational self-fulfilling prophecy""

Kenneth B. Clarks ideas about educational Self-fulfilling prophecies opened up minds to the effectiveness of teaching and the expectations teachers place upon students.

Literature, media, and the arts

In literature, self-fulfilling prophecies are often used as plot devices. They have been used in stories for millennia, but have gained a lot of popularity recently in the science fiction genre. They are typically used ironically, with the prophesied events coming to pass due to the actions of one trying to prevent the prophecy (a recent example would be the life of Anakin Skywalker, the fictional Jedi-turned-Sith Lord in George Lucas' Star Wars saga). They are also sometimes used as comic relief.

Classical

Many myths, legends, and fairy tales make use of this motif as a central element of narratives that are designed to illustrate inexorable fate, fundamental to the Hellenic world-view.[38] In a common motif, a child, whether newborn or not yet conceived, is prophesied to cause something that those in power do not want to happen. This may be the death of the powerful person; in more light-hearted versions, it is often the marriage of a poor or lower-class child to his own. The events come about, nevertheless, as a result of the actions taken to prevent them: frequently child abandonment sets the chain of events in motion.

Greek

In Greek literature a "prophete" is defined as "one who speaks for another."[39]

The best-known example from Greek legend is that of Oedipus. Warned that his child would one day kill him, Laius abandoned his newborn son Oedipus to die, but Oedipus was found and raised by others, and thus in ignorance of his true origins. When he grew up, Oedipus was warned that he would kill his father and marry his mother. Believing his foster parents were his real parents, he left his home and travelled to Greece, eventually reaching the city where his biological parents lived. There, he got into a fight with a stranger, his real father, killed him and married his widow, Oedipus' real mother.

Although the legend of Perseus opens with the prophecy that he will kill his grandfather Acrisius, and his abandonment with his mother Danaë, the prophecy is only self-fulfilling in some variants. In some, he accidentally spears his grandfather at a competition—an act that could have happened regardless of Acrisius' response to the prophecy. In other variants, his presence at the games is explained by his hearing of the prophecy, so that his attempt to evade it does cause the prophecy to be fulfilled. In still others, Acrisius is one of the wedding guests when Polydectes tried to force Danaë to marry him, and when Perseus turns them to stone with the Gorgon's head; as Polydectes fell in love with Danaë because Acrisius abandoned her at sea, and Perseus killed the Gorgon as a consequence of Polydectes' attempt to get rid of Danaë's son so that he could marry her, the prophecy fulfilled itself in these variants.

Greek historiography provides a famous variant: when the Lydian king Croesus asked the Delphic Oracle if he should invade Persia, the response came that if he did, he would destroy a great kingdom. Assuming this meant he would succeed, he attacked—but the kingdom he destroyed was his own.[40] In such an example, the prophecy prompts someone to action because he is led to expect a favorable result; but he achieves another, disastrous result which nonetheless fulfills the prophecy.

When it was predicted that Cronos would be overthrown by his son, and usurp his throne as King of the Gods, Cronus ate his children, each shortly after they were born. When Zeus was born, Cronos was thwarted by Rhea, who gave him a stone to eat instead, sending Zeus to be raised by Amalthea. Cronos' attempt to avoid the prophecy made Zeus his enemy, ultimately leading to its fulfilment.

Roman

The story of Romulus and Remus is another example. According to legend, a man overthrew his brother, the king. He then ordered that his two nephews, Romulus and Remus, be drowned, fearing that they would someday kill him as he did to his brother. The boys were placed in a basket and thrown in the Tiber River. A wolf found the babies and she raised them. Later, a shepherd found the twins and named them Romulus and Remus. As teenagers, they found out who they were. They killed their uncle, fulfilling the prophecy.

Arabic

A variation of the self-fulfilling prophecy is the self-fulfilling dream, which dates back to medieval Arabic literature. Several tales in the One Thousand and One Nights, also known as the Arabian Nights, use this device to foreshadow what is going to happen, as a special form of literary prolepsis. A notable example is "The Ruined Man Who Became Rich Again Through a Dream", in which a man is told in his dream to leave his native city of Baghdad and travel to Cairo, where he will discover the whereabouts of some hidden treasure. The man travels there and experiences misfortune after losing belief in the prophecy, ending up in jail, where he tells his dream to a police officer. The officer mocks the idea of foreboding dreams and tells the protagonist that he himself had a dream about a house with a courtyard and fountain in Baghdad where treasure is buried under the fountain. The man recognizes the place as his own house and, after he is released from jail, he returns home and digs up the treasure. In other words, the foreboding dream not only predicted the future, but the dream was the cause of its prediction coming true. A variant of this story later appears in English folklore as the "Pedlar of Swaffham".[41]

Another variation of the self-fulfilling prophecy can be seen in "The Tale of Attaf", where Harun al-Rashid consults his library (the House of Wisdom), reads a random book, "falls to laughing and weeping and dismisses the faithful vizier" Ja'far ibn Yahya from sight. Ja'far, "disturbed and upset flees Baghdad and plunges into a series of adventures in Damascus, involving Attaf and the woman whom Attaf eventually marries." After returning to Baghdad, Ja'far reads the same book that caused Harun to laugh and weep, and discovers that it describes his own adventures with Attaf. In other words, it was Harun's reading of the book that provoked the adventures described in the book to take place. This is an early example of reverse causality.[42] In the 12th century, this tale was translated into Latin by Petrus Alphonsi and included in his Disciplina Clericalis. In the 14th century, a version of this tale also appears in the Gesta Romanorum and Giovanni Boccaccio's The Decameron.[43]

Hinduism

The prophets involved in this religion are considered to be very superior, they have the highest ranking on the class system that one could have, and religious temples or shrines are built in their honor. It is believed in the Hindu religion that the prophets can foretell the future due to what they are experiencing in the "present" time.[39] Many of these prophets are seen to act as "saviors" and "restore justice to the world."[39]

Self-fulfilling prophecies appear in classical Sanskrit literature. In the story of Krishna in the Indian epic Mahabharata, the ruler of the Mathura kingdom, Kansa, afraid of a prophecy that predicted his death at the hands of his sister Devaki's son, had her cast into prison where he planned to kill all of her children at birth. After killing the first six children, and Devaki's apparent miscarriage of the seventh, Krishna (the eighth son) was born. As his life was in danger he was smuggled out to be raised by his foster parents Yashoda and Nanda in the village of Gokula. Years later, Kansa learned about the child's escape and kept sending various demons to put an end to him. The demons were defeated at the hands of Krishna and his brother Balarama. Krishna, as a young man returned to Mathura to overthrow his uncle, and Kansa was eventually killed by his nephew Krishna. It was due to Kansa's attempts to prevent the prophecy that it came true, thus fulfilling the prophecy.

Ruthenian

Oleg of Novgorod was a Varangian prince who ruled over the Rus people during the early tenth century. As old East Slavic chronicles say, it was prophesied by the pagan priests that Oleg's stallion would be the source of Oleg's death. To avoid this he sent the horse away. Many years later he asked where his horse was, and was told that it had died. He asked to see the remains and was taken to the place where the bones lay. When he touched the horse's skull with his boot a snake slithered from the skull and bit him. Oleg died, thus fulfilling the prophecy. In the Primary Chronicle, Oleg is known as the Prophet, ironically referring to the circumstances of his death. The story was romanticized by Alexander Pushkin in his celebrated ballad "The Song of the Wise Oleg". In Scandinavian traditions, this legend lived on in the saga of Orvar-Odd.

European fairy tales

Many fairy tales, such as The Devil With the Three Golden Hairs, The Fish and the Ring, The Story of Three Wonderful Beggars, or The King Who Would Be Stronger Than Fate, revolve about a prophecy that a poor boy will marry a rich girl (or, less frequently, a poor girl a rich boy).[44] This is story type 930 in the Aarne–Thompson classification scheme. The girl's father's efforts to prevent it are the reason why the boy ends up marrying her.

Another fairy tale occurs with older children. In The Language of the Birds, a father forces his son to tell him what the birds say: that the father would be the son's servant. In The Ram, the father forces his daughter to tell him her dream: that her father would hold an ewer for her to wash her hands in. In all such tales, the father takes the child's response as evidence of ill-will and drives the child off; this allows the child to change so that the father will not recognize his own offspring later and so offer to act as the child's servant.

In some variants of Sleeping Beauty, such as Sun, Moon, and Talia, the sleep is not brought about by a curse, but a prophecy that she will be endangered by flax (or hemp) results in the royal order to remove all the flax or hemp from the castle, resulting in her ignorance of the danger and her curiosity.

Shakespeare

Shakespeare's Macbeth is another classic example of a self-fulfilling prophecy. The three witches give Macbeth a prophecy that Macbeth will eventually become king, but afterwards, the offspring of his best friend will rule instead of his own. Macbeth tries to make the first half true while trying to keep his bloodline on the throne instead of his friend's. Spurred by the prophecy, he kills the king and his friend, something he, arguably, never would have done before. In the end, the evil actions he committed to avoid his succession by another's bloodline get him killed in a revolution.

The later prophecy by the first apparition of the witches that Macbeth should "Beware Macduff" is also a self-fulfilling prophecy. If Macbeth had not been told this, then he might not have regarded Macduff as a threat. Therefore, he would not have killed Macduff's family, and Macduff would not have sought revenge and killed Macbeth.

Fiction

Similar to Oedipus above, a more modern example would be Darth Vader in the Star Wars films, or Lord Voldemort in the Harry Potter franchise and the Big Three in Percy Jackson & the Olympians – each attempted to take steps to prevent action against them which had been predicted could cause their downfall, but instead created the conditions leading to it.

Another, less well-known, modern example occurred with the character John Mitchell on BBC Three's Being Human. The Disney television series That's So Raven stars Raven-Symoné as the title character with the ability to see into the future, revealing a strange situation. The extreme steps that the character takes to prevent the situation are almost always what lead to the situation. In George R. R. Martin's book series A Song of Ice and Fire, Cersei Lannister kills a friend of hers after hearing a prophecy, from Maggy the Frog, that said friend will soon die.

The song "Iron Man" by British heavy metal band Black Sabbath follows the story of a self-fulfilling prophecy of a man who travels into the future and sees the apocalypse and tries to warn people, but ends up causing the apocalypse.

New Thought

The law of attraction is a typical example of self-fulfilling prophecy. It is the name given to the belief that "like attracts like" and that by focusing on positive or negative thoughts, one can bring about positive or negative results.[45][46] According to this law, all things are created first by imagination, which leads to thoughts, then to words and actions. The thoughts, words and actions held in mind affect someone's intentions which makes the expected result happen. Although there are some cases where positive or negative attitudes can produce corresponding results (principally the placebo and nocebo effects), there is no scientific basis to the law of attraction.[47]

Sports

Robert Barnsley showed that in an elite group of ice hockey players, 40% are born between January and March, versus the approximately 25% as would be predicted by statistics, which could be explained by the relative age effect leading to selected players being exposed to higher levels of coaching, playing more games, and having better teammates. These factors make them actually become the best players, fulfilling the prophecy, while the real selection criterion was age.[48]

The same relative age effect has been noticed in football,[49] baseball,[50] basketball,[51] handball,[52] tennis[53] and many other sports.

Some researchers from 2008 found that in basketball, the head Coaches gave more biased feedback while the assistant coaches gave more critical feedback.[54] They predicted this was due to the external expectations from the coaches to the athletes which could have resulted in the Pygmalion effect with positive and negative results.[54]

Researcher Helen Brown published findings of two experiments performed on athletes in regard to the effect that the media has on them. In the first experiment, the athletes were labelled and categorized. During the experiment, the media reporter stated their expectations for the athlete, which would either be good, bad, or a neutral outlook. As a result, from this first experiment, it was concluded that the athlete's performance was impacted in both a good way and a bad way when they heard what the media's perception and outlook of their performance was.[55]

Experiment two took place in 2012 in London. The difference between experiment two and experiment one is that it happened face to face. The key components being studied in the athletes were their thought process as well as their responses to these expectations that the media was making about them. As a result from the second experiment performed, it was concluded that the media does impact athletes, it impacts their judgement, their thought process and it can even have a dangerous and destructive impact on some athletes.[55] This shows that the self-fulfilling prophecy was fulfilled because when the athlete and the media reporter came face to face and the media reporter began stating their expectations that they expect the athlete to fulfill they were able to "influence the athlete's cognition."[55]

Causal loop

A self-fulfilling prophecy may be a form of causality loop. Predestination does not necessarily involve a supernatural power, and could be the result of other "infallible foreknowledge" mechanisms.[56] Problems arising from infallibility and influencing the future are explored in Newcomb's paradox.[57] A notable fictional example of a self-fulfilling prophecy occurs in classical play Oedipus Rex, in which Oedipus becomes the king of Thebes, whilst in the process unwittingly fulfills a prophecy that he would kill his father and marry his mother. The prophecy itself serves as the impetus for his actions, and thus it is self-fulfilling.[58] The movie 12 Monkeys heavily deals with themes of predestination and the Cassandra complex, where the protagonist who travels back in time explains that he cannot change the past.[59]

See also

- Anticipation

- Begging the question

- Bootstrap paradox

- Cognitive behavioral therapy

- Confirmation bias

- Copycat effect

- Eschatology

- Expectation (epistemic)

- Fake it till you make it

- Mind over matter

- Moore's law

- Nineteen Eighty-Four

- Nominative determinism

- Reflexivity (social theory)

- Subject-expectancy effect

- Selection bias

- Self-defeating prophecy

- Self-licking ice cream cone

- Self-validating reduction

Notes

- Biggs, Michael (2013), "Prophecy, Self-Fulfilling/Self-Defeating", Encyclopedia of Philosophy and the Social Sciences, SAGE Publications, Inc., doi:10.4135/9781452276052.n292, ISBN 9781412986892

- Samaha, Adam (2011). "Regulation for the Sake of Appearance". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1943174. ISSN 1556-5068. S2CID 26933326.

- Houghton, David Patrick (September 2009). "The Role of Self-Fulfilling and Self-Negating Prophecies in International Relations". International Studies Review. 11 (3): 552–584. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2486.2009.00873.x. ISSN 1521-9488.

- Watson, James (2015). Self-fulfilling prophecy. Dictionary of Media and Communication Studies.

- Wineburg, Samuel S. (December 1987). "The Self-Fulfillment of the Self-Fulfilling Prophecy". Educational Researcher. 16 (9): 28–37. doi:10.3102/0013189x016009028. ISSN 0013-189X. S2CID 145466315.

- The child in America: Behavior problems and programs. W.I. Thomas and D.S. Thomas. New York: Knopf, 1928: 571–572

- Oxford English Dictionary. self-fulfilling.

1832 Morning Post 4 Apr. Suffice it to say, the licensed fabricators of self-fulfilling prophecies are again upon their stools.

- Bush, M (2014). Merton, Robert. The Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice.

- Merton, Robert K. (1948). "The Self-Fulfilling Prophecy". The Antioch Review. 8 (2): 193–210. doi:10.2307/4609267. ISSN 0003-5769. JSTOR 4609267.

- Merton, Robert King (1996). On social structure and science. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-52070-6. OCLC 34116334.

- "Self-Fulfilling Prophecy". Springer Reference. Springer Reference. Springer-Verlag. 2011. doi:10.1007/springerreference_180548.

- Popper, Karl (1976). Unended Quest: An Intellectual Autobiography. LaSalle, Illinois: Open Court. ISBN 0-87548-343-7. OCLC 2927208.

- Carrasco-Villanueva, M. A., El Efecto "Pricebo": Cómo los precios pueden influenciar la percepción sobre la calidad del cannabis y sus implicaciones en las políticas de precios. Pensamiento Crítico, vol. 22, no. 2, pp 175–210.

- Jussim, Lee; Harber, Kent D. (2005). "Teacher expectations and self-fulfilling prophecies: knowns and unknowns, resolved and unresolved controversies". Personality and Social Psychology Review. 9 (2): 131–155. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr0902_3. ISSN 1088-8683. PMID 15869379. S2CID 12853629.

- Myers, David G. (2010). Social psychology (Tenth ed.). New York, NY. ISBN 9780073370668. OCLC 667213323.

- Brameld, T. (1972). "Education as self-fulfilling prophecy". Phi Beta Kappa. 54 (1): 8–11, 58–61 [p. 9]. Quoted by Wilkins (1976), p. 176.

- Wilkins, William E. (1976). "The Concept of a Self-Fulfilling Prophecy". Sociology of Education. 49 (2): 175–183. doi:10.2307/2112523. ISSN 0038-0407. JSTOR 2112523.

- Adams, Glenn; Garcia, Donna M.; Purdie-Vaughns, Valerie; Steele, Claude M. (September 2006). "The detrimental effects of a suggestion of sexism in an instruction situation". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 42 (5): 602–615. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2005.10.004. ISSN 0022-1031.

- Allport, G. (1950). "The role of expectancy". In Cantrill, H. (ed.). The Tensions That Cause Wars. Urbana: University of Illinois. pp. 43–78.

- Delbaere, Kim; Close, Jacqueline C T; Brodaty, Henry; Sachdev, Perminder; Lord, Stephen R (2010). "Determinants of disparities between perceived and physiological risk of falling among elderly people: cohort study". The BMJ. 341: c4165. doi:10.1136/bmj.c4165. hdl:1854/LU-953701. PMC 2930273. PMID 20724399. S2CID 73024878.

- Phillips, David P (2001). "The Hound of the Baskervilles effect: natural experiment on the influence of psychological stress on timing of death". BMJ. 323 (7327): 1443–1446. doi:10.1136/bmj.323.7327.1443. PMC 61045. PMID 11751347.

- Gupta, Sumit (2 August 2020). "What Is The Baskerville Effect and Why Your Thoughts Matter?". Deployyourself. Retrieved 2020-12-01.

- Mi Cheong Cheong; Alexander B Artyukhin; Young-Jai You; Leon Avery. "An opioid-like system regulating feeding behavior in C. elegans". eLife. Figure 7. doi:10.7554/elife.06683.016.

- Rosenthal, R.; Jacobson, L. (1968). Pygmalion in the classroom: Teacher expectation and pupils' intellectual development. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

- Aronson, Elliot; Wilson, Timothy D.; Pearson, Robin M. Akert (2004). Social Psychology (5th ed.). Prentice Hall College Div. ISBN 0-131-78686-5.

- Rosenthal, Robert (2003). "Covert communication in laboratories, classrooms, and the truly real world" (PDF). Current Directions in Psychological Science. Blackwell. 12 (5): 151–154. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.t01-1-01250. S2CID 26644967. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- Rosenthal, Robert; Jacobson, Lenore (2003). Pygmalion in the Classroom. Crown House. ISBN 9781904424062.

- Matheson, Kimberly; Foster, Mindi D.; Bombay, Amy; McQuaid, Robyn J.; Anisman, Hymie (2019). "Traumatic Experiences, Perceived Discrimination, and Psychological Distress Among Members of Various Socially Marginalized Groups". Frontiers in Psychology. 10: 416. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00416. PMC 6403156. PMID 30873095.

- Downey, Geraldine; Freitas, Antonio L.; Michaelis, Benjamin; Khouri, Hala (1998). "The self-fulfilling prophecy in close relationships: Rejection sensitivity and rejection by romantic partners". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 75 (2): 545–560. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.75.2.545. ISSN 1939-1315. PMID 9731324.

- Rosecrance, Richard N.; Miller, Steven E., eds. (2014). The next great war? : the roots of World War I and the risk of U.S.-China conflict. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-32677-3. OCLC 896343523.

- Thomas, Raju G. C. (1986). Indian security policy. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-5819-4. OCLC 741479156.

- Hinnebusch, Raymond (January 2007). "The US Invasion of Iraq: Explanations and Implications". Critique: Critical Middle Eastern Studies. 16 (3): 209–228. doi:10.1080/10669920701616443. ISSN 1066-9922. S2CID 143931232.

- Jervis, Robert L. (June 2003). "The Confrontation between Iraq and the US: Implications for the Theory and Practice of Deterrence". European Journal of International Relations. 9 (2): 315–337. doi:10.1177/1354066103009002006. ISSN 1354-0661. S2CID 145446765.

- Houghton, David Patrick (September 2009). "The Role of Self-Fulfilling and Self-Negating Prophecies in International Relations". International Studies Review. 11 (3): 552–584. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2486.2009.00873.x.

- Citation error. See inline comment how to fix.

- Guha, Martin (2004). "The Concise Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology and Behavioral Science (3rd edition)2004417Edited by W. Edward Craighead and Charles B. Nemeroff. The Concise Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology and Behavioral Science (3rd edition). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley 2004. vii + 1,112 pp., ISBN: 0 471 22036 1 £78.50/$150 Also available as an e‐book (ISBN 0 471 60415 1)". Reference Reviews. 18 (8): 12. doi:10.1108/09504120410565611. ISSN 0950-4125.

- ""The accumulation of stereotype-based self-fulfilling prophecies": Correction to Madon et al. (2018)". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 116 (1): 68. 2019. doi:10.1037/pspi0000173. ISSN 1939-1315. PMID 30596447. S2CID 58617821.

- See Nemesis, Moirai, Erinyes. "Very often the bases for false definitions and consequent self-fulfilling prophecies are deeply rooted in the individual or group norms and are subsequently difficult to change". (Wilkins 1976:177).

- "Prophecy | Encyclopedia of Time: Science, Philosophy, Theology, & Culture - Credo Reference". search.credoreference.com. Retrieved 2020-08-19.

- Herodotus Histories 1.88

- Irwin, Robert (2003). The Arabian Nights: A Companion. Tauris Parke Paperbacks. pp. 193–194. ISBN 1-86064-983-1.

- Irwin, Robert (2003). The Arabian Nights: A Companion. Tauris Parke Paperbacks. p. 199. ISBN 1-86064-983-1.

- Ulrich Marzolph, Richard van Leeuwen, Hassan Wassouf (2004). The Arabian Nights Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 109. ISBN 1-57607-204-5.

- Stith Thompson, The Folktale, p 139, University of California Press, Berkeley Los Angeles London, 1977

- Whittaker, S.: Secret attraction Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, The Montreal Gazette, May 12, 2007.

- Redden, Guy: Magic Happens: A New Age Metaphysical Mystery Tour, Journal of Australian Studies 101

- Carroll, Robert Todd (12 September 2014). "law of attraction". The Skeptic's Dictionary. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- Gladwell, Malcolm (2008). "1 – The Matthew Effect". Outliers. Little, Brown and Company. pp. 20–25. ISBN 978-0-316-01792-3.

- Tim Goodenough. "Is it because of talent that athletes succeed?". rugbyIQ. Archived from the original on 2011-08-14.

- Helsen, WF; Starkes, JL; Van Winckel, J (2000-11-01). "Effect of a change in selection year on success in male soccer players". American Journal of Human Biology. 12 (6): 729–735. doi:10.1002/1520-6300(200011/12)12:6<729::AID-AJHB2>3.0.CO;2-7. PMID 11534065.

- Herring, Chad H.; Beyer, Kyle S.; Fukuda, David H. (2021). "Relative Age Effects as Evidence of Selection Bias in Major League Baseball Draftees (2013–2018)". The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 35 (3): 644–651. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000003951. ISSN 1064-8011. PMID 33470599. S2CID 231651477.

- Faria, Larissa Oliveira; Bredt, Sarah da Glória Teles; Ribeiro, Amanda Isadora; Galatti, Larissa Rafaela; Albuquerque, Maicon Rodrigues (2021-09-24). "Inequality in Brazilian basketball: the birthplace effect". Revista Brasileira de Cineantropometria & Desempenho Humano. 23. doi:10.1590/1980-0037.2021v23e76932. ISSN 1415-8426. S2CID 244177676.

- Rubia, Alfonso de la; Bjørndal, Christian Thue; Sánchez-Molina, Joaquín; Yagüe, José María; Calvo, Jorge Lorenzo; Maroto-Izquierdo, Sergio (2020). "The relationship between the relative age effect and performance among athletes in World Handball Championships". PLOS ONE. 15 (3): e0230133. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1530133R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0230133. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 7098603. PMID 32214322.

- Ulbricht, Alexander; Fernandez-Fernandez, Jaime; Mendez-Villanueva, Alberto; Ferrauti, Alexander (2015). "The Relative Age Effect and Physical Fitness Characteristics in German Male Tennis Players". Journal of Sports Science & Medicine. 14 (3): 634–642. ISSN 1303-2968. PMC 4541129. PMID 26336351.

- Solomon, Gloria B.; Striegel, David A.; Eliot, John F.; Heon, Steve N.; Maas, Jana L.; Wayda, Valerie K. (1996-03-01). "The self-fulfilling prophecy in college basketball: Implications for effective coaching". Journal of Applied Sport Psychology. 8 (1): 44–59. doi:10.1080/10413209608406307. ISSN 1041-3200.

- Brown, Helen (August 2014). "The influence of media expectations on athletes: An explorative study". Sport & Exercise Psychology Review. 10: 2 – via 20-22.

- Craig, William Lane (1987). "Divine Foreknowledge and Newcomb's Paradox". Philosophia. 17 (3): 331–350. doi:10.1007/BF02455055. S2CID 143485859.

- Dummett, Michael (1996). The Seas of Language. Oxford University Press. pp. 356, 370–375. ISBN 9780198240112.

- Dodds, E.R. (1966), Greece & Rome 2nd Ser., Vol. 13, No. 1, 37–49

- Klosterman, Chuck (2009). Eating the Dinosaur (1st Scribner hardcover ed.). New York: Scribner. pp. 60–62. ISBN 9781439168486.

Further reading

- Sayers, Dorothy L.: Oedipus Simplex: Freedom and Fate in Folklore and Fiction.