Shaolin Monastery

Shaolin Monastery (少林寺 Shàolínsì), also known as Shaolin Temple, is a renowned temple recognized as the birthplace of Chan Buddhism and the cradle of Shaolin Kung Fu. It is located at the foot of Wuru Peak of the Songshan mountain range in Dengfeng County, Henan Province, China. The name reflects its location in the ancient grove (林 lín) of Mount Shaoshi, in the hinterland of the Songshan mountains. Mount Song occupied a prominent position among Chinese sacred mountains as early as the 1st century BC, when it was proclaimed one of the Five Holy Peaks (五岳 wǔyuè). It is located some thirty miles (about forty-eight kilometers) southeast of Luoyang, the former capital of the Northern Wei Dynasty (386–534), and forty-five miles (about seventy-two kilometers) southwest of Zhengzhou, the modern capital of Henan Province.[1]

| Shaolin Monastery | |

|---|---|

少林寺 | |

Shaolin Monastery in 2006 | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Buddhism |

| Status | Active |

| Location | |

| Location | Dengfeng, Zhengzhou, Henan, China |

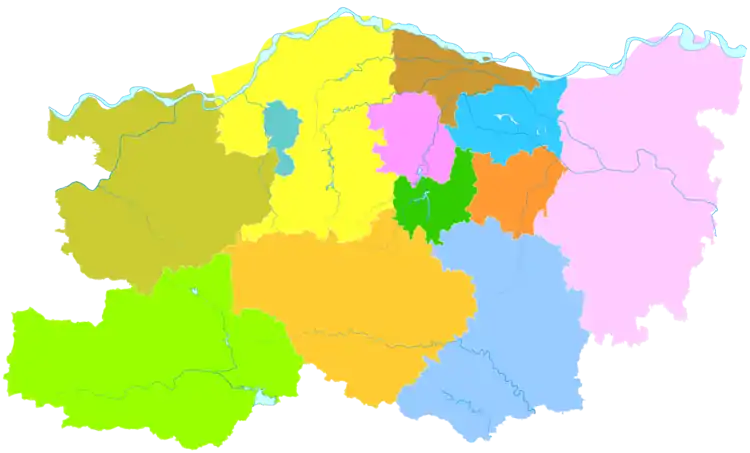

Shown within Henan | |

| Geographic coordinates | 34°30′27″N 112°56′07″E |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Chinese architecture |

| Date established | 495 |

| Website | |

| shaolin | |

| Location | China |

| Part of | Historic Monuments of Dengfeng in "The Centre of Heaven and Earth" |

| Criteria | Cultural: (iv) |

| Reference | 1305-005 |

| Inscription | 2010 (34th Session) |

| Shaolin Monastery | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Shaolin Temple" in Chinese | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 少林寺 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Temple of Shao[shi Mountain] Woods" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

As the first Shaolin abbot, Batuo devoted himself to translating Buddhist scriptures and to preaching doctrines to hundreds of his followers. According to legend, Bodhidharma, the 28th patriarch of Mahayana Buddhism in India, arrived at the Shaolin Temple in 527. He spent nine years meditating in a cave of the Wuru Peak and initiated the Chinese Chan tradition at the Shaolin Temple. Thereafter, Bodhidharma was honored as the first patriarch of Chan Buddhism.[2]

The Temple's historical architectural complex, standing out for its great aesthetic value and its profound cultural connotations, has been inscribed in the UNESCO World Heritage List. Apart from its contribution to the development of Chinese Buddhism, as well as for its historical, cultural, and artistic heritage, the temple is famous for its martial arts tradition.[1] Shaolin monks have been devoted to research, creation, and continuous development and perfecting of Shaolin kung fu.

The main pillars of Shaolin culture are Chan Buddhism (禅 Chán), martial arts (武 wǔ), Buddhist art (艺 yì), and traditional Chinese medicine (医 yī). This cultural heritage, still constituting the daily temple life, is representative of Chinese civilization. A large number of celebrities, political figures, eminent monks, Buddhist disciples, and many other people, come to the temple to visit, make pilgrimages, and hold cultural exchanges.[3] In addition, owing to the work of official Shaolin overseas cultural centers and foreign disciples, Shaolin culture has spread around the world as a distinctive symbol of Chinese culture and a means of foreign cultural exchange.[4]

At present, Shaolin Temple is a Global Low-carbon Ecological Scenic Spot and a National 5A-level Tourist Attraction in China.[5] It has been awarded the highest-level category used by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism and attributed to the most important and best-maintained tourist attractions in the People's Republic of China.[6]

History

Northern Wei and Northern Zhou dynasties

According to the Continued Biographies of Eminent Monks (AD 645) by Daoxuan, Shaolin Monastery was built on the north side of Shaoshi, the central peak of Mount Song, one of the Sacred Mountains of China, by Emperor Xiaowen of the Northern Wei dynasty in AD 477, to accommodate the Indian teacher Batuo, a dhyāna master who came to China to spread Buddhist teachings beside the capital Luoyang.[7] Batuo, also referred to in the Chinese sources as Fotuo (in Sanskrit: Buddhabhadra), had met the emperor several years before. He had enjoyed Emperor Xiaowen's sponsorship ever since he arrived in Pingcheng via the silk route around 490.[8] Yang Xuanzhi, in the Record of the Buddhist Monasteries of Luoyang (AD 547), and Li Xian, in the Ming Yitongzhi (1461), concur with Daoxuan's location and attribution. The Jiaqing Chongxiu Yitongzhi (1843) specifies that this monastery, located in the province of Henan, was built in the twentieth year of the Taihe era of the Northern Wei dynasty, that is, the monastery was built in AD 495.

Thanks to Batuo, Shaolin became an important center for the study and translation of original Buddhist scriptures. It also became a place of gathering for esteemed Buddhist masters. Historical sources on the early origins of Shaolin kung fu show that at this time, martial arts practice was existent in the temple.[9] Batuo's teaching was continued by his two disciples, Sengchou (僧稠Sēngchóu, 480–560) and Huiguang (慧光Huìguāng, 487–536).

In the first year of the Yongping era (506), Indian monks Lenamoti 勒那摩提 (in Sanskrit: Ratnamati) and Putiliuzhi 菩提流支 (in Sanskrit: Bodhiruci) came to Shaolin to set up a scripture translation hall. Together with Huiguang, they translated master Shiqin's (世親 Shìqīn; in Sanskrit: Vasubandhu) commentary on the Ten Stages Sutra (Sanskrit: Daśabhūmika Sūtra; simplified Chinese: 十地经), an early, influential Mahayana Buddhist scripture. After that, Huiguang promoted the Vinaya in Four Parts (四分律Sì fēn lǜ; Sanskrit: Dharmagupta-Vinaya), which formed the theoretical basis of the Luzong (律宗 Lǜzōng) School of Buddhism, formed during the Tang Dynasty by Dao Xuan (596–667).

In the third year of the Xiaochang era (527) of Emperor Xiaoming of Northern Wei, Bodhidharma (达摩 Dá mó), the 28th patriarch of Mahayana Buddhism in India, came to the Shaolin Temple. The Indian arrived as a Chan Buddhist missionary and traveled for decades throughout China before, settling on Mount Song in the 520s.[10] Bodhidharma's teachings were primarily based on Lankavatara Sutra, which contains the conversation between Gautama Buddha and Bodhisattva Mahamatti, who is considered the first patriarch of Chan tradition.

Using the teachings of Batuo and his disciples as a foundation, Bodhidharma introduced Chan Buddhism, and the Shaolin Temple community gradually grew to become the center of Chinese Chan Buddhism. Bodhidharma's teaching was transmitted to his disciple Huike, who the legend says cut off his arm to show his determination and devotion to the teachings of his master. Huike was forced to leave the temple during the persecution of Buddhism and Daoism (574–580) by Emperor Wu of Northern Zhou. In 580, Emperor Jing of Northern Zhou restored the temple and renamed it Zhi‘ao Temple (陟岵寺 Zhìhù sì).[11]

The idea that Bodhidharma founded martial arts at the Shaolin Temple was spread in the 20th century. However, martial arts historians have shown this legend stems from a 17th-century qigong manual known as the Yijin Jing.[12] The oldest available copy was published in 1827.[13] The composition of the text itself has been dated to 1624.[14] Even then, the association of Bodhidharma with martial arts only became widespread as a result of the 1904–1907 serialization of the novel The Travels of Lao Ts'an in Illustrated Fiction Magazine:[15]

One of the most recently invented and familiar of the Shaolin historical narratives is a story that claims that the Indian monk Bodhidharma, the supposed founder of Chinese Chan (Zen) Buddhism, introduced boxing into the monastery as a form of exercise around a.d. 525. This story first appeared in a popular novel, The Travels of Lao T'san, published as a series in a literary magazine in 1907. This story was quickly picked up by others and spread rapidly through publication in a popular contemporary boxing manual, Secrets of Shaolin Boxing Methods, and the first Chinese physical culture history published in 1919. As a result, it has enjoyed vast oral circulation and is one of the most "sacred" of the narratives shared within Chinese and Chinese-derived martial arts. That this story is clearly a twentieth-century invention is confirmed by writings going back at least 250 years earlier, which mention both Bodhidharma and martial arts but make no connection between the two.[16]

Other scholars see an earlier connection between Da Mo and the Shaolin Monastery. The monk and his disciples are said to have lived at a spot about a mile from the Shaolin Temple that is now a small nunnery.[17] In the 6th century, around AD 547, The Record of the Buddhist Monasteries says Da Mo visited the area near Mount Song.[18][19] In AD 645, The Continuation of the Biographies of Eminent Monks describes him as being active in the Mount Song region.[19][20] Around AD 710, Da Mo is identified specifically with the Shaolin Temple (Precious Record of Dharma's Transmission or Chuanfa Baoji)[19][21] and writes of his sitting facing a wall in meditation for many years. It also speaks of Huike's many trials in his efforts to receive instruction from Da Mo. In the 11th century (1004), a work embellishes the Da Mo legends with great detail. A stele inscription at the Shaolin Monastery dated to 728 Ad reveals Da Mo residing on Mount Song.[22] Another stele from AD 798 speaks of Huike seeking instruction from Da Mo. Another engraving dated to 1209 depicts the barefoot saint holding a shoe, according to the ancient legend of Da Mo. A plethora of 13th- and 14th-century steles feature Da Mo in various roles. One 13th-century image shows him riding a fragile stalk across the Yangtze River.[23] In 1125, a special temple was constructed in his honor at the Shaolin Monastery.[24]

Sui, Tang, Wu Zhou, and Song dynasties

Emperor Wen of Sui, who was a Buddhist himself, returned the temple's original name and offered to its community 100 hectares of land. Shaolin thus became a large temple with hundreds of hectares of fertile land and large properties. It was once again the center of Chan Buddhism, with eminent monks from all over China visiting on a regular basis.

At the end of the Sui dynasty, the Shaolin Temple, with its huge monastery properties, became the target of thieves and bandits. The monks organized forces within their community to protect the temple and fight against the intruders. At the beginning of the Tang dynasty, thirteen Shaolin monks helped Li Shimin, the future second emperor of the Tang dynasty, in his fight against Wang Shichong. They captured Shichong's nephew Wang Renze, whose army was stationed in the Cypress Valley. In 626, Li Shimin, later known as Emperor Taizong, sent an official letter of gratitude to the Shaolin community for the help they provided in his fight against Shichong and thus the establishment of the Tang Dynasty.[25] According to legend, Emperor Taizong granted the Shaolin Temple extra land and a special "imperial dispensation" to consume meat and alcohol during reign of the Tang dynasty. If true, this would have made Shaolin the only temple in China that did not prohibit alcohol. Regardless of historical veracity, these rituals are not practiced today.[26] This legend is not corroborated in any period documents, such as the Shaolin Stele, erected in AD 728. The stele does not list any such imperial dispensation as reward for the monks' assistance during the campaign against Wang Shichong; only land and a water mill are granted.[27] The Tang dynasty also established several Shaolin branch monasteries throughout the country and formulated policies for Shaolin monks and soldiers to assist local governments and regular military troops. Shaolin Temple also became a place where emperors and high officials would come for temporary reclusion. Emperor Gaozong of Tang and Empress Wu Zetian often visited the Shaolin Temple for good luck and made large donations. Empress Wu also paid several visits to the Shaolin Temple to discuss Chan philosophy with high monk Tan Zong. During the Tang and Song dynasties, the Shaolin Temple was extremely prosperous. It had more than 14,000 acres of land, 540 acres of temple grounds, more than 5,000 rooms, and more than 2,000 monks. The Chan Buddhist School founded by Bodhidharma flourished during the Tang dynasty and was the largest Buddhist school of that time.[28]

Information about the first century of the Northern Song dynasty is scarce. The rulers of Song supported the development of Buddhism, and Chan established itself as dominant over other Buddhist schools. Around 1093, Chan master Baoen (报恩Bào'ēn) promoted the Caodong School in the Shaolin Temple and achieved what is known in Buddhist history as "revolutionary turn into Chan". This meant that the Shaolin Temple officially became a Chan Buddhist Temple, while up to that point it was a Lǜzōng temple specialized in Vinaya, with a Chan Hall.

Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties

At the beginning of the Yuan dynasty, Emperor Shizu of Yuan installed the monk Xueting Fuyu (雪庭福裕, 1203–1275) as the abbot of Shaolin and put him in charge of all the temples in the Mount Song area. During this period, the abbot undertook important construction work, including the building of the Bell Tower and the Drum Tower. He also introduced the generational lineage system of the Shaolin disciples through a 70-character poem—each character in line corresponding to the name of the next generation of disciples. In 1260, Fuyu was honored with the title of the Divine Buddhist Master and in 1312 posthumously named Duke of Jin (晉國公 Jìn guó gōng) by the Yuan emperor.

The fall of the Yuan dynasty and the establishment of the Ming dynasty brought much unrest, in which the temple community needed to defend itself from rebels and bandits. During the Red Turban Rebellion in the 14th century, bandits ransacked the monastery for its real or supposed valuables, destroying much of the temple and driving the monks away. The monastery was likely abandoned from 1351 or 1356 (the most likely dates for the attack) to at least 1359, when government troops retook Henan. The events of this period would later figure heavily in 16th-century legends of the temple's patron saint Vajrapani, with the story being changed to claim a victory for the monks, rather than a defeat.[29]

With the establishment of the Ming dynasty by mid-14th century, Shaolin recovered, and a large part of the monastic community that fled during the Red Turban attacks returned. At the beginning of the Ming dynasty, the government did not advocate martial arts. During the reign of the Jiajing Emperor, Japanese pirates harassed China's coastal areas, and generals Yu Dayou and Qi Jiguang led their troops against the pirates. During his stay in Fujian, Qi Jiguang convened martial artists from all over China, including local Shaolin monks, to develop a set of boxing and staff fighting techniques to be used against Japanese pirates. Owing to the monks' merits in fighting against the Japanese, the government renovated the temple on a large scale, and Shaolin enjoyed certain privileges, such as food tax exemption, granted by the government. Afterward, Shaolin monks were recruited by the Ming government at least six times to participate in wars. Due to their outstanding contribution to Chinese military success, the imperial court built monuments and buildings for Shaolin Temple on numerous occasions. This also contributed to the establishment of the legitimacy of Shaolin kung fu in the national martial arts community. During the Ming Dynasty (in mid-16th century), Shaolin reached its apogee and held its position as the central place of the Caodong School of Chan Buddhism.

In 1641, rebel forces led by Li Zicheng sacked the monastery due to the monks' support of the Ming dynasty and the possible threat they posed to the rebels. This effectively destroyed the temple's fighting force.[30] The temple fell into ruin and was home to only a few monks until the early 18th century, when the government of the Qing dynasty patronized and restored it.[31]

During the Qing dynasty, Shaolin Temple was favored by Qing emperors. In the 43rd year of the Kangxi Emperor's reign (1704), the emperor gifted a tablet to the temple, with the characters 少林寺(Shàolín sì) engraved on it in his calligraphy (originally hung in the Heavenly King Hall and later moved by the Mountain Gate). In the 13th year of the Yongzheng Emperor's reign (1735), important reconstructions were financed by the court, including the rebuilding of the gate and the Thousand Buddha's Hall. In the 15th year of his rule (1750), the Qianlong Emperor personally visited Shaolin Temple, stayed at the abbot's room overnight, and wrote poems and tablet inscriptions.

A well-known story of the temple from this period is that it was destroyed by the Qing government for supposed anti-Qing activities. Variously said to have taken place in 1647 under the Shunzhi Emperor, in 1674, 1677, or 1714 under the Kangxi Emperor, or in 1728 or 1732 under the Yongzheng Emperor, this destruction is also supposed to have helped spread Shaolin martial arts throughout China by means of the five fugitive monks. Some accounts claim that a supposed southern Shaolin Temple was destroyed instead of, or in addition to, the temple in Henan: Ju Ke, in the Qing bai lei chao (1917), locates this temple in Fujian. These stories commonly appear in legendary or popular accounts of martial history and in wuxia fiction.

While these latter accounts are popular among martial artists and often serve as origin stories for various martial arts styles, they are viewed by scholars as fictional. The accounts are known through often inconsistent 19th-century secret society histories and popular literature, and also appear to draw on both Fujianese folklore and popular narratives, such as the classical novel Water Margin. Modern scholarly attention to the tales is mainly concerned with their role as folklore.[32][33][34][35]

Republic of China

In the early days of the Republic of China, Shaolin Temple was repeatedly hit by wars. In 1912, monk Yunsong Henglin from the Dengfeng County Monks Association was elected by the local government as the head of the Shaolin Militia (Shaolin Guarding Corps). He organized the guards and trained them in combat skills to maintain local order. In the autumn of 1920, famine and drought hit Henan province, which led to thieves surging throughout the area and endangering the local community. Henglin led the militia to fight the bandits on different occasions, thus enabling dozens of villages in the temple's surroundings to live and work in peace.[36]

In the late 1920s, Shaolin monks became embroiled in the warlords' feuds that swept the plains of northern China. They sided with General Fan Zhongxiu (1888–1930), who had studied martial arts at Shaolin Temple as a child, against Shi Yousan (1891–1940). Fan was defeated and, in the spring of 1928, Yousan's troops entered Dengfeng and Shaolin Temple, which served as Fan Zongxiu's headquarters. On 15 March, Shi Yousan's subordinate Feng Yuxiang set fire to the monastery, destroying some of its ancient towers and halls. The flames partially damaged the "Shaolin Monastery Stele" (which recorded the politically astute choice made by other Shaolin clerics fifteen hundred years earlier), the Dharma Hall, the Heavenly King Hall, Mahavira Hall, Bell Tower, Drum Tower, Sixth Ancestor Hall, Chan Hall, and other buildings, causing the death of a number of monks. A large number of cultural relics and 5,480 volumes of Buddhist scriptures were destroyed in the fire.[37]

Japan's activities in Manchuria in the early 1930s made the National Government very worried. The military then launched a strong patriotic movement to defend the country and resist the enemy. The Nanjing Central Martial Arts Center and Wushu Institute, together with other martial arts institutions, were established around the country as part of this movement. The government also organized martial arts events such as "Martial arts returning to Shaolin". This particular event served to encourage people to remember the importance of patriotism by celebrating the contribution of Shaolin martial arts to the country's defense from foreign invasion at numerous occasions throughout history.

People's Republic of China

Since the founding of the People's Republic of China, the state has recognized five official religions, including Buddhism, and established institutional relationships with them through religious associations. The Buddhist Association of China was founded in 1953 and was disbanded in the late 1960s, during the Cultural Revolution, then reactivated following the end of that period.

During the Cultural Revolution, the monks of Shaolin Temple were forced to return to secular life, Buddha statues were destroyed, and temple properties were invaded. After this period ended, Shaolin Temple was repaired and rebuilt. The buildings and other material heritage that was destroyed, including the Mahavira Hall and the stone portraying "Bodhidharma facing the wall", were reconstructed according to their originals. Others, such as the ancient martial arts training ground, the Pagoda Forest, and some stone carvings that survived, still remain in their original state. In December 1996, Chuzu Temple and Shaolin Temple Pagoda Forest (No. 4-89) were listed as national key cultural relic protection units. Shaolin Temple leadership aimed for its historical architectural complex to become a United Nations World Heritage site in order to obtain annual funding for maintenance and development from the UN. After repeated submissions, their application was finally accepted by the 34th World Heritage Committee on 1 August 2010. UNESCO reviewed and approved eight sites and eleven architectural complexes, including Shaolin's Resident Hall, Pagoda Forest, and Chuzu Temple as World Cultural Heritage.[38]

On 22 March 2006, Russian President, Vladimir Putin, visited Shaolin Temple and watched a kung fu performance. He was the first foreign head of state to visit Shaolin Temple in its history.[39]

In May 2007, Shaolin Temple was named a National 5A Scenic Spot by the China National Tourism Administration.[40]

In 2009, Shaolin Temple established Fengyinghang Co., Ltd. to prepare for the construction of the first Overseas Shaolin Cultural Center Headquarters (Hong Kong Shaolin Temple) outside of mainland China.

In April 2013, the Shaolin Temple Sutra Pavilion was selected as a National Key Protection Unit for Ancient Books, as its collection of documents and books related to kung fu theory and practice is unique in China.[41]

Current leadership

The current abbot of Shaolin Temple is Venerable Master Shi Yongxin, the thirtieth-generation abbot of Shaolin Temple. Born as Liu Yingcheng, he comes from a devout Buddhist family from Yingshang, Anhui province. At the age of seventeen, he came to Shaolin Temple in Mount Songshan, where the Abbot Master Xingzheng took him as a disciple. His Buddhist name, "Yongxin", means the one who "always believes in Buddhism". Later, he studied at the Yunju Mountain in Jianxi Province, Jiuhua Mountain in Anhui Province, and Guangji Temple in Beijing. After having received his precepts in Puzhao Temple in Jianxi Province in 1984, he returned to Shaolin Temple. He continued serving Master Xingzheng and was also a member of the newly established Democratic Management Committee of Shaolin Temple. In 1987, after his master died, he took over the position of Chairman of Shaolin Temple Management Committee and presided over the work of the monastery. In March 1993, Shi Yongxin was elected a member of the Henan Provincial Political Consultative Conference and in October of the same year, the Head of the Buddhist Association of China. He was elected as Deputy to the Ninth (1998), Tenth (2003), Eleventh (2008), and Twelfth (2013) National People's Congress. In July 1998, he became the President of the Henan Buddhist Association. In August 1999, Shi Yongxin was honored as the abbot of Shaolin Temple. In 2002 and again in 2010, he was elected Vice President of the Buddhist Association of China. In 2010, he also became the Director of the Overseas Communication Committee of Buddhist Association of China.[42]

Abbot Shi Yongxin's published works in recent years include texts in the Dew of Chan journal series and the books My Heart My Buddha, Shaolin Temple in My Heart, among others. He has also compiled dozens of books, including Shaolin Temple, Collection of Shaolin Kung Fu (second series), Medical Secret Records of Shaolin Kung Fu, Encyclopedia of Shaolin Temple (three volumes), Chan Buddhism Grand Ceremony (200 volumes), Chinese Martial Arts Grand Ceremony (101 volumes), Medical Encyclopedia of Chinese Buddhism (101 volumes), Essays of International Seminars on Chan Culture, Science of Shaolin Anthology, Shaolin Kung Fu, Chan Happiness, The Heart Sutra of Bodhisattva, and others.[43]

Acknowledgements

Ancient honors

Before Emperor Wuzong's Huichang prosecution of Buddhism and Taoism, Shaolin Temple enjoyed tax exemptions.

Modern acknowledgements

- In 2004, the California State House of Representatives and Senate passed two votes to officially establish 21 March as California Songshan Shaolin Temple Day.[44]

- In 2007, the temple was proclaimed as a National 5A-level Scenic Spot, a Global Low-carbon Ecological Scenic Spot, a patriotism education base for religious circles of the People's Republic of China, and an education base for respecting and caring for the elderly of the People's Republic of China.[40]

- On 1 August 2010, during the UNESCO 34th World Heritage Committee, eight buildings, including Shaolin Temple, Pagoda Forest, and Chuzu Temple were listed as World Cultural Heritage sites.[45]

- In April 2013, the Shaolin Temple Sutra Pavilion was selected as a National Key Protection Unit for Ancient Books.[46]

- In May 2013, the State Council of the People's Republic of China listed the ancient buildings of Shaolin Temple (No. 7-1162) as the seventh batch of national key cultural relic protection units.[47]

International promotion of Shaolin cultural heritage

Shaolin Temple is an important religious and cultural institution, both in China and internationally.[48] Since the founding of the People's Republic of China, and especially since the 1970s, cultural exchanges between Shaolin Temple and the rest of the world have continuously improved in terms of content, scale, frequency, and scope. The temple has been visited by European and American dancers, martial artists, NBA players, Hollywood movie stars, but also renowned monks from traditional Buddhist countries such as Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Nepal, and Sri Lanka. Also, a number of political leaders, such as Swedish King Carl XVI Gustaf, British Queen Elizabeth II, Spanish King Juan Carlos I, Australia's former prime minister John Howard, South Africa former president Nelson Mandela, Russian president Vladimir Putin, former US secretary of state Henry Kissinger, and Taiwanese politician James Soong have met with the temple's abbot.

Currently, there are more than forty overseas cultural institutions established by the temple's leadership and its disciples in dozens of countries around the world. Shaolin monks come to the centers to teach Buddhist classics, martial arts, meditation, etc. Another way of promoting Shaolin's intangible cultural heritage in the world is through Shaolin Cultural Festivals, the first of which was held in North America. These festivals and similar events convey the spiritual connotation of Chinese culture and Eastern values to societies internationally.[49]

Shaolin culture

Shaolin Temple has developed numerous complementary cultural aspects that permeate and mutually reinforce each other and are inseparable, when it comes to presenting the temple's material and intangible cultural heritage. The most prominent aspects are those of Chan (禅 Chán), martial arts (武 wǔ), traditional medicine (中医 zhōngyī), and art (艺 yì). Shaolin culture is rooted in Mahayana Buddhism, while the practice of Chan is its nucleus and finally, the martial arts, traditional medicine, and art are its manifestations. Thanks to the efforts of the abbot Shi Yongxin, the monastic community, and the temple's disciples from all over the world, Shaolin culture continues to grow. During its historical development, Shaolin culture has also integrated the essential values of Confucianism and Taoism.

The contemporary temple establishment offers to all interested individuals and groups, regardless of cultural, social, and religious values, the chance to experience Shaolin culture through the Shaolin cultural exchange program. This program offers an introduction to Chan meditation, Shaolin kung fu, Chan medicine, calligraphy, art, archery, etc. Chan practice is supposed to help the individual in attaining calm and patience necessary for living optimistically, meaningfully, wisely, and with compassion. Ways of practicing Chan are numerous, and they range from everyday activities such as eating, drinking, walking, or sleeping, to specialized practices such as meditation, martial arts, and calligraphy.

Shaolin kung fu is manifested through a system of different skills that are based on attack and defense movements with the form (套路 tàolù) as its unit. One form is a combination of different movements. The structure of movements is founded on ancient Chinese medical knowledge, which is compatible with the laws of body movement. Within the temple, the forms are taught with a focus on integration of the principles of complementarity and opposition. This means that Shaolin kung fu integrates dynamic and static components, yin and yang, hardness and softness, etc.

The Shaolin community invests great effort in safeguarding, developing, and innovating its heritage. Following the ancient Chinese principle of harmony between heaven and humans, temple masters work on the development of the most natural body movement in order to achieve the full potential of human expression.

Shaolin has developed activities related to the international promotion of its cultural heritage. In 2012, the first international Shaolin cultural festival was organized in Germany, followed by festivals in the US and England. Official Shaolin cultural centers exist in numerous countries in Europe, the US, Canada, and Russia. Every year, the temple hosts more than thirty international events with the aim to promote cultural exchange.

Shaolin temple buildings

The temple's inside area is 160 by 360 meters (520 ft × 1,180 ft), that is, 57,600 square meters (620,000 sq ft). It has seven main halls on the axis and seven other halls around, with several yards around the halls. The temple structure includes:

- Shanmen (山门) (built in 1735; the entrance tablet, written in golden characters, reads "Shaolin Temple" (少林寺; shaolinsi) in black background by the Kangxi Emperor of the Qing dynasty in 1704).

- Forest of Steles (碑林; beilin)

- Ciyun Hall (慈雲堂; ciyuntang) (built in 1686; changed in 1735; reconstructed in 1984). It includes the Corridor of Steles (碑廊; beilang), which has 124 stone tablets of various dynasties, from the Northern Qi dynasty (550–570).

- West Arrival Hall (西来堂; xilaitang) a.k.a. Kung Fu Hall (锤谱堂; chuiputang) (built in 1984).

- Four Heavenly Kings Hall (天王殿; tianwangdian) (built during the Yuan dynasty; repaired during the Ming and Qing dynasties).

- Bell tower (钟楼; zhonglou) (built in 1345; reconstructed in 1994; the bell was built in 1204).

- Drum tower (鼓楼; gulou) (built in 1300; reconstructed in 1996).

- Kimnara Palace Hall (紧那罗殿; jinnaluodian) (reconstructed in 1982).

- Sixth Patriarch Hall (六祖堂; liuzutang)

- Mahavira Hall (大雄宝殿; daxiongbaodian) a.k.a. Main Hall or Great Hall (built circa 1169; reconstructed in 1985).

- Dining Hall (built during the Tang dynasty; reconstructed in 1995).

- Sutra Room

- Dhyana Halls (reconstructed in 1981).

- Guest Reception Hall

- Dharma Hall (Sermon) Hall (法堂; fatang) a.k.a. Scripture Room (藏经阁; zang jing ge) (reconstructed in 1993).

- East & West Guest Rooms

- Abbot's Room (方丈室; fangzhangshi) (built during the early Ming dynasty).

- Standing in Snow Pavilion (立雪亭; lixueting) a.k.a. Bodhidharma Bower (达摩庭; damoting) (reconstructed in 1983).

- Manjusri Hall (wenshudian) (reconstructed in 1983).

- Samantabhadra Hall

- White Robe (Avalokitesvara) Hall (白衣殿; baiyi (Guan yin) dian) a.k.a. Kung Fu Hall (quanpudian) (built during the Qing dynasty).

- Ksitigarbha Hall (地臧殿; di zang dian) (built during the early Qing dynasty; reconstructed in 1979).

- Thousand Buddha Hall (千佛殿; qianfodian) a.k.a. Vairocana Pavilion (毗庐阁; piluge) (built in 1588; repaired in 1639,1776).

- Ordination Platform (built in 2006).

- Monks' Rooms

- Shaolin Pharmacy Bureau (built in 1217; reconstructed in 2004).

- Bodhidharma Pavilion (chuzuan) (first built during the Song dynasty)

- Bodhidharma Cave

- Forest of Pagodas Yard (塔林院; talinyuan) (built before 791). It has 240 tomb pagodas of various sizes from the Tang, Song, Jin, Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties (618–1911).

- Shaolin Temple Wushu Guan (Martial arts hall)

A mural painting in the temple (early 19th century)

A mural painting in the temple (early 19th century) Shaolin Monastery Stele on Mount Song (皇唐嵩岳少林寺碑), erected in AD 728

Shaolin Monastery Stele on Mount Song (皇唐嵩岳少林寺碑), erected in AD 728 A tree within the Shaolin Monastery used by the monks to practice finger-punching

A tree within the Shaolin Monastery used by the monks to practice finger-punching The Pagoda forest (wide view)

The Pagoda forest (wide view) The Pagoda forest (close view), located about 300 meters (980 ft) west of the Shaolin Monastery in Henan

The Pagoda forest (close view), located about 300 meters (980 ft) west of the Shaolin Monastery in Henan

See also

- Shaolin Temple UK

- Bayon- Buddhist temple depicting martial arts bas-relief

- Angkor Wat- Buddhist–Hindu temple depicting martial arts bas-relief

References

- Shahar 2008

- "Shaolin Monk Corps--Shaolin Temple". www.shaolin.org.cn.

- 外国总统多次造访 少林文化已走向世界. 人民网. 2009年11月23日 [2014年3月24日]. (原始内容存档于2016年3月4日

- 250余名美国弟子拜谒少林寺. 搜狐网. 2013年7月4日 [2014年3月23日]. (原始内容存档于2014年3月23日.); (马明达. 走向世界的少林文化. 《体育文化导刊》 (国家体育总局体育文化发展中心). 2004年, (01期) [2014-03-24]. ISSN 1671-1572. (原始内容存档于2014-03-24)

- Xinhuanet 19 June 2013 [ 2014-03-24 ] The original content was archived on 24 March 2014

- Shaolin Temple Longmen Grotto Yuntai Mountain 3 Scenic Spot was selected as 5A Scenic Spot. Dahe.com.

- Shahar 2008, p. 9.

- Wei shu, 114.3040; Ware, trans., “Wei Shou on Buddhism,” pp. 155–156; Shahar 2008

- Lu Zhouxiang 2019

- Shahar 2008;Shi Daoxuan 2014; Lu Zhouxiang 2019

- 少林寺简介. 少林寺官网. [2014-03-23]. (原始内容存档于2014-02-18)

- Shahar 2008, pp. 165–173.

- Matsuda 1986.

- Lin 1996, p. 183.

- Henning 1994.

- Henning & Green 2001, p. 129.

- Ferguson, Andy. Tracking Bodhidharma: A Journey to the Heart of Chinese Culture. p. 267.

- Louyang Quilan Ji

- Shahar 2008, p. 13.

- Xu Gaoseng Zhuan

- Record of Dharma's Transmission of Chuanfa Baoji

- Shahar 2008, p. 14.

- Shahar 2008, p. 15.

- Shahar 2008, p. 16.

- Shahar 2008; Lu Zhouxiang 2019

- Polly, Matthew (2007). American Shaolin: Flying Kicks, Buddhist Monks, and the Legend of Iron Crotch: An Odyssey in the New China. Gotham Books. p. 37. ISBN 9781592402625. Retrieved 7 November 2010 – via Google Books.

- Tonami, Mamoru (1990). The Shaolin Monastery Stele on Mount Song. Translated by P.A. Herbert. Kyoto: Istituto Italiano di Cultura / Scuola di Studi sull' Asia Orientale. pp. 17–18, 35.

- 少林寺简介. 少林寺官网. [2014-03-23]. (原始内容存档于2014-02-18)

- Shahar 2008, pp. 83–85.

- Shahar 2008, pp. 185–188.

- Shahar 2008, p. 182–183, 190.

- Shahar 2008, p. 183–185.

- Kennedy, Brian; Guo, Elizabeth (2005). Chinese Martial Arts Training Manuals: A Historical Survey. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-55643-557-7.

- McKeown, Trevor W. "Shaolin Temple Legends, Chinese Secret Societies, and the Chinese Martial Arts". In Green; Svinth (eds.). Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia of History and Innovation. pp. 112–113.

- Murry, Dian; Qin Baoqi (1995). The Origins of the Tiandihui: The Chinese Triads in Legend and History. Stanford: Stanford University Press. pp. 154–156. ISBN 978-0-8047-2324-4.

- 一代高僧:恒林法师. 菩萨在线. 12 July 2013 [2014-03-24]. (原始内容存档于2014-03-24); 恒林. 少林寺官网. 2010-02-26 [2014-03-24]. (原始内容存档于2014-03-24

- 少林寺简介. 少林寺官网. [2014-03-23]. 原始内容

- 少林寺获列入世界遗产名录. 联合早报. 1 August 2010 [2010-11-12]. (原始内容存档于2010-11-24)

- 普京参观少林寺 观看武僧表演. 新华网. 2006年3月23日 [2010年11月13日]. (原始内容存档于2010年10月8日)

- 少林寺龙门石窟云台山3景区入选5A景区. 大河网. 2007年5月17日 [2014年3月23日]. 原始内容存档于2014年3月24日

- 少林寺藏经阁入选全国古籍重点保护单位. 搜狐网. 2013年4月26日 [2014年3月24日]. (原始内容存档于2014年3月24日

- Shi Yongxin, Shaolin Temple in my Heart, edition 2020

- "少林寺,少林文化,少林寺官方网站". Shaolin.org.cn. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- 美国加州“嵩山少林寺日”确立庆典活动落幕. 腾讯网. 2004年3月26日 [2014年3月23日]. (原始内容存档于2014年3月23日)

- 少林寺获列入世界遗产名录. 联合早报. 1 August 2010 [2010-11-12].(原始内容存档于2010-11-24)

- 少林寺藏经阁入选全国古籍重点保护单位. 搜狐网. 2013年4月26日 [2014年3月24日]. (原始内容存档于2014年3月24日)

- 第七批全国重点文物保护单位 少林寺名列其中. 光明网. 6 May 2013 [2014-03-24]. 原始内容存档于2014-03-24

- 中原文化多靓丽 融入全球传少林. 新浪网. 2013年10月9日 [2014-03-24]. (原始内容存档于2014-03-24

- 中原文化多靓丽 融入全球传少林. 新浪网. 2013年10月9日 [2014-03-24]. (原始内容存档于2014-03-24).

Sources

- Henning, Stanley (1994). "The Chinese Martial Arts in Historical Perspective" (PDF). Journal of the Chenstyle Taijiquan Research Association of Hawaii. 2 (3): 1–7.

- Henning, Stan; Green, Tom (2001). "Folklore in the Martial Arts". In Green, Thomas A. (ed.). Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO.

- Lin, Boyuan (1996). Zhōngguó wǔshù shǐ 中國武術史. Taipei: Wǔzhōu chūbǎnshè 五洲出版社.

- Matsuda, Ryuchi (1986). Zhōngguó wǔshù shǐlüè 中國武術史略 (in Chinese). Taipei: Danqing tushu.

- Shahar, Meir (2008). The Shaolin Monastery: history, religion, and the Chinese martial arts. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3110-3.