Shunzhi Emperor

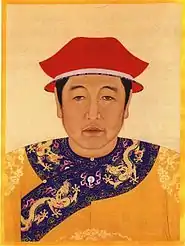

The Shunzhi Emperor (15 March 1638 – 5 February 1661) was the second emperor of the Qing dynasty of China, and the first Qing emperor to rule over China proper, reigning from 1644 to 1661. A committee of Manchu princes chose him to succeed his father, Hong Taiji (1592–1643), in September 1643, when he was five years old. The princes also appointed two co-regents: Dorgon (1612–1650), the 14th son of the Qing dynasty's founder Nurhaci (1559–1626), and Jirgalang (1599–1655), one of Nurhaci's nephews, both of whom were members of the Qing imperial clan.

| Shunzhi Emperor 順治帝 | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Emperor of the Qing dynasty | |||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 8 October 1643 – 5 February 1661 | ||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Hong Taiji | ||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Kangxi Emperor | ||||||||||||||||

| Regents | Dorgon (1643–1650) Jirgalang (1643–1647) | ||||||||||||||||

| Emperor of China | |||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 1644–1661 | ||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Chongzhen Emperor (Ming dynasty) | ||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Kangxi Emperor (Qing dynasty) | ||||||||||||||||

| Born | Aisin Gioro Fulin (愛新覺羅·福臨) 15 March 1638 (崇德三年 正月 三十日) Yongfu Palace, Mukden Palace | ||||||||||||||||

| Died | 5 February 1661 (aged 22) (順治十八年 正月 七日) Hall of Mental Cultivation | ||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Xiao Mausoleum, Eastern Qing tombs | ||||||||||||||||

| Consorts | Consort Jing

(m. 1651; dep. 1653)Empress Xiaohuizhang

(m. 1654)Empress Xiaoxian

(m. 1656; died 1660)Empress Xiaokangzhang

(m. 1653) | ||||||||||||||||

| Issue | Fuquan, Prince Yuxian of the First Rank Kangxi Emperor Changning, Prince Gong of the First Rank Longxi, Prince Chunjing of the First Rank Princess Gongque of the Second Rank | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| House | Aisin Gioro | ||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | Qing | ||||||||||||||||

| Father | Hong Taiji | ||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Empress Xiaozhuangwen | ||||||||||||||||

| Shunzhi Emperor | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 順治帝 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 顺治帝 | ||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Smoothly-Ruling Emperor | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

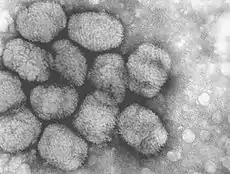

From 1643 to 1650, political power lay mostly in the hands of Dorgon. Under his leadership, the Qing Empire conquered most of the territory of the fallen Ming dynasty (1368–1644), chased Ming loyalist regimes deep into the southwestern provinces, and established the basis of Qing rule over China proper despite highly unpopular policies such as the "hair cutting command" of 1645, which forced Qing subjects to shave their forehead and braid their remaining hair into a queue resembling that of the Manchus. After Dorgon's death on the last day of 1650, the young Shunzhi Emperor started to rule personally. He tried, with mixed success, to fight corruption and to reduce the political influence of the Manchu nobility. In the 1650s, he faced a resurgence of Ming loyalist resistance, but by 1661 his armies had defeated the Qing Empire's last enemies, seafarer Koxinga (1624–1662) and the Prince of Gui (1623–1662) of the Southern Ming dynasty, both of whom would succumb the following year. The Shunzhi Emperor died at the age of 22 of smallpox, a highly contagious disease that was endemic in China, but against which the Manchus had no immunity. He was succeeded by his third son Xuanye, who had already survived smallpox, and who reigned for sixty years under the era name "Kangxi" (hence he was known as the Kangxi Emperor). Because fewer documents have survived from the Shunzhi era than from later eras of the Qing dynasty, the Shunzhi era is a relatively little-known period of Qing history.

"Shunzhi" was the name of this ruler's reign period in Chinese. This title had equivalents in Manchu and Mongolian because the Qing imperial family was Manchu and ruled over many Mongol tribes that helped the Qing to conquer the Ming dynasty. The emperor's personal name was Fulin, and the posthumous name by which he was worshipped at the Imperial Ancestral Temple was Shizu (Wade–Giles: Shih-tsu; Chinese: 世祖).

Historical background

In the 1580s, when China was ruled by the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), a number of Jurchen tribes lived in Manchuria.[2] In a series of campaigns from the 1580s to the 1610s, Nurhaci (1559–1626), the leader of the Jianzhou Jurchens, unified most Jurchen tribes under his rule.[3] One of his most important reforms was to integrate Jurchen clans under flags of four different colors—yellow, white, red, and blue—each further subdivided into two to form an encompassing social and military system known as the Eight Banners.[4] Nurhaci gave control of these Banners to his sons and grandsons.[5] Around 1612, Nurhaci renamed his clan Aisin Gioro ("golden Gioro" in the Manchu language), both to distinguish his family from other Gioro lines and to allude to an earlier dynasty that had been founded by Jurchens, the Jin ("golden") dynasty that had ruled northern China from 1115 to 1234.[6] In 1616 Nurhaci formally announced the foundation of the "Later Jin" dynasty, effectively declaring his independence from the Ming.[7] Over the next few years he wrested most major cities in Liaodong from Ming control.[8] His string of victories ended in February 1626 at the siege of Ningyuan, where Ming commander Yuan Chonghuan defeated him with the help of recently acquired Portuguese cannon.[9] Probably wounded during the battle, Nurhaci died a few months later.[10]

Nurhaci's son and successor Hong Taiji (1592–1643) continued his father's state-building efforts: he concentrated power into his own hands, modeled the Later Jin's government institutions on Chinese ones, and integrated Mongol allies and surrendered Chinese troops into the Eight Banners.[11] In 1629 he led an incursion to the outskirts of Beijing, during which he captured Chinese craftsmen who knew how to cast Portuguese cannon.[12] In 1635 Hong Taiji renamed the Jurchens the "Manchus", and in 1636 changed the name of his polity from "Later Jin" to "Qing".[13] After capturing the last remaining Ming cities in Liaodong, by 1643 the Qing were preparing to attack the struggling Ming dynasty, which was crumbling under the combined weight of financial bankruptcy, devastating epidemics, and large-scale bandit uprisings fed by widespread starvation.[14]

Becoming emperor

When Hong Taiji died on 21 September 1643 without having named a successor, the fledgling Qing state faced a possibly serious crisis.[15] Several contenders—namely Nurhaci's second and eldest surviving son Daišan, Nurhaci's fourteenth and fifteenth sons Dorgon and Dodo (both born to the same mother), and Hong Taiji's eldest son Hooge—started to vie for the throne.[16] With his brothers Dodo and Ajige, Dorgon (31 years old) controlled the Plain and Bordered White Banners, Daišan (60) was in charge of the two Red Banners, whereas Hooge (34) had the loyalty of his father's two Yellow Banners.[17]

The decision about who would become the new Qing emperor fell to the Deliberative Council of Princes and Ministers, which was the Manchus' main policymaking body until the emergence of the Grand Council in the 1720s.[18] Many Manchu princes argued that Dorgon, a proven military leader, should become the new emperor, but Dorgon refused and insisted that one of Hong Taiji's sons should succeed his father.[19] To recognize Dorgon's authority while keeping the throne in Hong Taiji's descent line, the members of the council named Hong Taiji's ninth son, Fulin, as the new emperor, but decided that Dorgon and Jirgalang (a nephew of Nurhaci who controlled the Bordered Blue Banner) would act as the five-year-old child's regents.[19] Fulin was officially crowned emperor of the Qing dynasty on 8 October 1643; it was decided that he would reign under the era name "Shunzhi."[20] Because the Shunzhi reign is not well documented, it constitutes a relatively little-known period of Qing history.[21]

Dorgon's regency (1643–1650)

.jpg.webp)

A quasi emperor

On 17 February 1644, Jirgalang, who was a capable military leader but looked uninterested in managing state affairs, willingly yielded control of all official matters to Dorgon.[22] After an alleged plot by Hooge to undermine the regency was exposed on 6 May of that year, Hooge was stripped of his title of Imperial Prince and his co-conspirators were executed.[23] Dorgon soon replaced Hooge's supporters (mostly from the Yellow Banners) with his own, thus gaining closer control of two more Banners.[24] By early June 1644, he was in firm control of the Qing government and its military.[25]

In early 1644, just as Dorgon and his advisors were pondering how to attack the Ming, peasant rebellions were dangerously approaching Beijing. On 24 April of that year, rebel leader Li Zicheng breached the walls of the Ming capital, pushing the Chongzhen Emperor to hang himself on a hill behind the Forbidden City.[26] Hearing the news, Dorgon's Chinese advisors Hong Chengchou and Fan Wencheng (范文程; 1597–1666) urged the Manchu prince to seize this opportunity to present themselves as avengers of the fallen Ming and to claim the Mandate of Heaven for the Qing.[27] The last obstacle between Dorgon and Beijing was Ming general Wu Sangui, who was garrisoned at Shanhai Pass at the eastern end of the Great Wall.[28] Himself caught between the Manchus and Li Zicheng's forces, Wu requested Dorgon's help in ousting the bandits and restoring the Ming.[29] When Dorgon asked Wu to work for the Qing instead, Wu had little choice but to accept.[30] Aided by Wu Sangui's elite soldiers, who fought the rebel army for hours before Dorgon finally chose to intervene with his cavalry, the Qing won a decisive victory against Li Zicheng at the Battle of Shanhai Pass on 27 May.[31] Li's defeated troops looted Beijing for several days until Li left the capital on 4 June with all the wealth he could carry.[32]

Settling in the capital

After six weeks of mistreatment at the hands of rebel troops, the Beijing population sent a party of elders and officials to greet their liberators on 5 June.[33] They were startled when, instead of meeting Wu Sangui and the Ming heir apparent, they saw Dorgon, a horseriding Manchu with his shaved forehead, present himself as the Prince Regent.[34] In the midst of this upheaval, Dorgon installed himself in the Wuying Palace (武英殿), the only building that remained more or less intact after Li Zicheng had set fire to the palace complex on 3 June.[35] Banner troops were ordered not to loot; their discipline made the transition to Qing rule "remarkably smooth."[36] Yet at the same time as he claimed to have come to avenge the Ming, Dorgon ordered that all claimants to the Ming throne (including descendants of the last Ming emperor) should be executed along with their supporters.[37]

On 7 June, just two days after entering the city, Dorgon issued special proclamations to officials around the capital, assuring them that if the local population accepted to shave their forehead, wear a queue, and surrender, the officials would be allowed to stay at their post.[38] He had to repeal this command three weeks later after several peasant rebellions erupted around Beijing, threatening Qing control over the capital region.[39]

Dorgon greeted the Shunzhi Emperor at the gates of Beijing on 19 October 1644.[40] On 30 October the six-year-old monarch performed sacrifices to Heaven and Earth at the Altar of Heaven.[41] The southern cadet branch of Confucius' descendants who held the title Wujing boshi 五經博士 and the sixty-fifth generation descendant of Confucius to hold the title Duke Yansheng in the northern branch both had their titles reconfirmed on 31 October.[41] A formal ritual of enthronement for Fulin was held on 8 November, during which the young emperor compared Dorgon's achievements to those of the Duke of Zhou, a revered regent from antiquity.[42] During the ceremony, Dorgon's official title was raised from "Prince Regent" to "Uncle Prince Regent" (Shufu shezheng wang 叔父攝政王), in which the Manchu term for "Uncle" (ecike) represented a rank higher than that of imperial prince.[43] Three days later Dorgon's co-regent Jirgalang was demoted from "Prince Regent" to "Assistant Uncle Prince Regent" (Fu zheng shuwang 輔政叔王).[44] In June 1645, Dorgon eventually decreed that all official documents should refer to him as "Imperial Uncle Prince Regent" (Huang shufu shezheng wang 皇叔父攝政王), which left him one step short of claiming the throne for himself.[44]

One of Dorgon's first orders in the new Qing capital was to vacate the entire northern part of Beijing to give it to Bannermen, including Han Chinese Bannermen.[45] The Yellow Banners were given the place of honor north of the palace, followed by the White Banners east, the Red Banners west, and the Blue Banners south.[46] This distribution accorded with the order established in the Manchu homeland before the conquest and under which "each of the banners was given a fixed geographical location according to the points of the compass."[47] Despite tax remissions and large-scale building programs designed to facilitate the transition, in 1648 many Chinese civilians still lived among the newly arrived Banner population and there was still animosity between the two groups.[48] Agricultural land outside the capital was also marked off (quan 圈) and given to Qing troops.[49] Former landowners now became tenants who had to pay rent to their absentee Bannermen landlords.[49] This transition in land use caused "several decades of disruption and hardship."[49]

In 1646, Dorgon also ordered that the civil examinations for selecting government officials be reestablished. From then on they were held regularly every three years as under the Ming. In the very first palace examination held under Qing rule in 1646, candidates, most of whom were northern Chinese, were asked how the Manchus and Han Chinese could be made to work together for a common purpose.[50] The 1649 examination inquired about "how Manchus and Han Chinese could be unified so that their hearts were the same and they worked together without division."[51] Under the Shunzhi Emperor's reign, the average number of graduates per session of the metropolitan examination was the highest of the Qing dynasty ("to win more Chinese support"), until 1660 when lower quotas were established.[52]

To promote ethnic harmony, in 1648 an imperial decree formulated by Dorgon allowed Han Chinese civilians to marry women from the Manchu Banners, with the permission of the Board of Revenue if they were registered daughters of officials or commoners, or the permission of their banner company captain if they were unregistered commoners. Only later in the dynasty were these policies allowing intermarriage rescinded.[45][53][54]

Conquest of China proper

Under the reign of Dorgon—whom historians have variously called "the mastermind of the Qing conquest" and "the principal architect of the great Manchu enterprise"—the Qing subdued almost all of China and pushed loyalist "Southern Ming" resistance into the far southwestern reaches of China. After repressing anti-Qing revolts in Hebei and Shandong in the Summer and Fall of 1644, Dorgon sent armies to root out Li Zicheng from the important city of Xi'an (Shaanxi province), where Li had reestablished his headquarters after fleeing Beijing in early June 1644.[56] Under the pressure of Qing armies, Li was forced to leave Xi'an in February 1645, and he was killed—either by his own hand or by a peasant group that had organized for self-defense in this time of rampant banditry—in September 1645 after fleeing though several provinces.[57]

From newly captured Xi'an, in early April 1645 the Qing mounted a campaign against the rich commercial and agricultural region of Jiangnan south of the lower Yangtze River, where in June 1644 a Ming imperial prince had established a regime loyal to the Ming.[lower-alpha 1] Factional bickering and numerous defections prevented the Southern Ming from mounting an efficient resistance.[lower-alpha 2] Several Qing armies swept south, taking the key city of Xuzhou north of the Huai River in early May 1645 and soon converging on Yangzhou, the main city on the Southern Ming's northern line of defense.[62] Bravely defended by Shi Kefa, who refused to surrender, Yangzhou fell to Manchu artillery on 20 May after a one-week siege.[63] Dorgon's brother Prince Dodo then ordered the slaughter of Yangzhou's entire population.[64] As intended, this massacre terrorized other Jiangnan cities into surrendering to the Qing.[65] Indeed, Nanjing surrendered without a fight on 16 June after its last defenders had made Dodo promise he would not hurt the population.[66] The Qing soon captured the Ming emperor (who died in Beijing the following year) and seized Jiangnan's main cities, including Suzhou and Hangzhou; by early July 1645, the frontier between the Qing and the Southern Ming had been pushed south to the Qiantang River.[67]

On 21 July 1645, after Jiangnan had been superficially pacified, Dorgon issued a most inopportune edict ordering all Chinese men to shave their forehead and to braid the rest of their hair into a queue identical to those of the Manchus.[68] The punishment for non-compliance was death.[69] This policy of symbolic submission helped the Manchus in telling friend from foe.[70] For Han officials and literati, however, the new hairstyle was shameful and demeaning (because it breached a common Confucian directive to preserve one's body intact), whereas for common folk cutting their hair was the same as losing their virility.[71] Because it united Chinese of all social backgrounds into resistance against Qing rule, the hair cutting command greatly hindered the Qing conquest.[72] The defiant population of Jiading and Songjiang was massacred by former Ming general Li Chengdong (李成東; d. 1649), respectively on 24 August and 22 September.[73] Jiangyin also held out against about 10,000 Qing troops for 83 days. When the city wall was finally breached on 9 October 1645, the Qing army led by Ming defector Liu Liangzuo (劉良佐; d. 1667) massacred the entire population, killing between 74,000 and 100,000 people.[74] These massacres ended armed resistance against the Qing in the Lower Yangtze.[75] A few committed loyalists became hermits, hoping that for lack of military success, their withdrawal from the world would at least symbolize their continued defiance against foreign rule.[75]

After the fall of Nanjing, two more members of the Ming imperial household created new Southern Ming regimes: one centered in coastal Fujian around the "Longwu Emperor" Zhu Yujian, Prince of Tang—a ninth-generation descendant of Ming founder Zhu Yuanzhang—and one in Zhejiang around "Regent" Zhu Yihai, Prince of Lu.[76] But the two loyalist groups failed to cooperate, making their chances of success even lower than they already were.[77] In July 1646, a new Southern Campaign led by Prince Bolo sent Prince Lu's Zhejiang court into disarray and proceeded to attack the Longwu regime in Fujian.[78] Zhu Yujian was caught and summarily executed in Tingzhou (western Fujian) on 6 October.[79] His adoptive son Koxinga fled to the island of Taiwan with his fleet.[79] Finally in November, the remaining centers of Ming resistance in Jiangxi province fell to the Qing.[80]

In late 1646 two more Southern Ming monarchs emerged in the southern province of Guangzhou, reigning under the era names of Shaowu (紹武) and Yongli.[80] Short of official costumes, the Shaowu court had to purchase robes from local theater troops.[80] The two Ming regimes fought each other until 20 January 1647, when a small Qing force led by Li Chengdong captured Guangzhou, killed the Shaowu Emperor, and sent the Yongli court fleeing to Nanning in Guangxi.[81] In May 1648, however, Li mutinied against the Qing, and the concurrent rebellion of another former Ming general in Jiangxi helped Yongli to retake most of south China.[82] This resurgence of loyalist hopes was short-lived. New Qing armies managed to reconquer the central provinces of Huguang (present-day Hubei and Hunan), Jiangxi, and Guangdong in 1649 and 1650.[83] The Yongli emperor had to flee again.[83] Finally on 24 November 1650, Qing forces led by Shang Kexi captured Guangzhou and massacred the city's population, killing as many as 70,000 people.[84]

Meanwhile, in October 1646, Qing armies led by Hooge (the son of Hong Taiji who had lost the succession struggle of 1643) reached Sichuan, where their mission was to destroy the kingdom of bandit leader Zhang Xianzhong.[85] Zhang was killed in a battle against Qing forces near Xichong in central Sichuan on 1 February 1647.[86] Also late in 1646 but further north, forces assembled by a Muslim leader known in Chinese sources as Milayin (米喇印) revolted against Qing rule in Ganzhou (Gansu). He was soon joined by another Muslim named Ding Guodong (丁國棟).[87] Proclaiming that they wanted to restore the Ming, they occupied a number of towns in Gansu, including the provincial capital Lanzhou.[87] These rebels' willingness to collaborate with non-Muslim Chinese suggests that they were not only driven by religion.[87] Both Milayin and Ding Guodong were captured and killed by Meng Qiaofang (孟喬芳; 1595–1654) in 1648, and by 1650 the Muslim rebels had been crushed in campaigns that inflicted heavy casualties.[88]

Transition and personal rule (1651–1661)

Purging Dorgon's clique

Dorgon's unexpected death on 31 December 1650 during a hunting trip triggered a period of fierce factional struggles and opened the way for deep political reforms.[89] Because Dorgon's supporters were still influential at court, Dorgon was given an imperial funeral and was posthumously elevated to imperial status as the "Righteous Emperor" (yi huangdi 義皇帝).[90] On the same day of mid-January 1651, however, several officers of the White Banners led by former Dorgon supporter Ubai arrested Dorgon's brother Ajige for fear he would proclaim himself as the new regent; Ubai and his officers then named themselves presidents of several Ministries and prepared to take charge of the government.[91]

Meanwhile, Jirgalang, who had been stripped of his title of regent in 1647, gathered support among Banner officers who had been disgruntled during Dorgon's rule.[92] In order to consolidate support for the emperor in the two Yellow Banners (which had belonged to the Qing monarch since Hong Taiji) and to gain followers in Dorgon's Plain White Banner, Jirgalang named them the "Upper Three Banners" (shang san qi 上三旗; Manchu: dergi ilan gūsa), which from then on were owned and controlled by the emperor.[93] Oboi and Suksaha, who would become regents for the Kangxi Emperor in 1661, were among the Banner officers who gave Jirgalang their support, and Jirgalang appointed them to the Council of Deliberative Princes to reward them.[92]

On 1 February, Jirgalang announced that the Shunzhi Emperor, who was about to turn thirteen, would now assume full imperial authority.[92] The regency was thus officially abolished. Jirgalang then moved to the attack. In late February or early March 1651 he accused Dorgon of usurping imperial prerogatives: Dorgon was found guilty and all his posthumous honors were removed.[92] Jirgalang continued to purge former members of Dorgon's clique and to bestow high ranks and nobility titles upon a growing number of followers in the Three Imperial Banners, so that by 1652 all of Dorgon's former supporters had been either killed or effectively removed from government.[94]

Factional politics and the fight against corruption

On 7 April 1651, barely two months after he seized the reins of government, the Shunzhi Emperor issued an edict announcing that he would purge corruption from officialdom.[95] This edict triggered factional conflicts among literati that would frustrate him until his death.[96] One of his first gestures was to dismiss grand academician Feng Quan (馮銓; 1595–1672), a northern Chinese who had been impeached in 1645 but was allowed to remain in his post by Prince Regent Dorgon.[97] The Shunzhi Emperor replaced Feng with Chen Mingxia (ca. 1601–1654), an influential southern Chinese with good connections in Jiangnan literary societies.[98] Though later in 1651 Chen was also dismissed on charges of influence peddling, he was reinstated in his post in 1653 and soon became a close personal advisor to the sovereign.[99] He was even allowed to draft imperial edicts just as Ming Grand Secretaries used to.[100] Still in 1653, the Shunzhi Emperor decided to recall the disgraced Feng Quan, but instead of balancing the influence of northern and southern Chinese officials at court as the emperor had intended, Feng Quan's return only intensified factional strife.[101] In several controversies at court in 1653 and 1654, the southerners formed one bloc opposed to the northerners and the Manchus.[102] In April 1654, when Chen Mingxia spoke to northern official Ning Wanwo (寧完我; d. 1665) about restoring the style of dress of the Ming court, Ning immediately denounced Chen to the emperor and accused him of various crimes including bribe-taking, nepotism, factionalism, and usurping imperial prerogatives.[103] Chen was executed by strangulation on 27 April 1654.[104]

In November 1657, a major cheating scandal erupted during the Shuntian provincial-level examinations in Beijing.[105] Eight candidates from Jiangnan who were also relatives of Beijing officials had bribed examiners in the hope of being ranked higher in the contest.[106] Seven examination supervisors found guilty of receiving bribes were executed, and several hundred people were sentenced to punishments ranging from demotion to exile and confiscation of property.[107] The scandal, which soon spread to Nanjing examination circles, uncovered the corruption and influence-peddling that was rife in the bureaucracy, and that many moralistic officials from the north attributed to the existence of southern literary clubs and to the decline of classical scholarship.[108]

Chinese style of rule

During his short reign, the Shunzhi Emperor encouraged Han Chinese to participate in government activities and revived many Chinese-style institutions that had been either abolished or marginalized during Dorgon's regency. He discussed history, classics, and politics with grand academicians such as Chen Mingxia (see previous section) and surrounded himself with new men such as Wang Xi (王熙; 1628–1703), a young northern Chinese who was fluent in Manchu.[109] The "Six Edicts" (Liu yu 六諭) that the Shunzhi Emperor promulgated in 1652 were the predecessors to the Kangxi Emperor's "Sacred Edicts" (1670): "bare bones of Confucian orthodoxy" that instructed the population to behave in a filial and law-abiding fashion.[110] In another move toward Chinese-style government, the sovereign reestablished the Hanlin Academy and the Grand Secretariat in 1658. These two institutions based on Ming models further eroded the power of the Manchu elite and threatened to revive the extremes of literati politics that had plagued the late Ming, when factions coalesced around rival grand secretaries.[111]

To counteract the power of the Imperial Household Department and the Manchu nobility, in July 1653 the Shunzhi Emperor established the Thirteen Offices (十三衙門), or Thirteen Eunuch Bureaus, which were supervised by Manchus, but manned by Chinese eunuchs rather than Manchu bondservants.[112] Eunuchs had been kept under tight control during Dorgon's regency, but the young emperor used them to counter the influence of other power centers such as his mother the Empress Dowager and former regent Jirgalang.[113] By the late 1650s eunuch power became formidable again: they handled key financial and political matters, offered advice on official appointments, and even composed edicts.[114] Because eunuchs isolated the monarch from the bureaucracy, Manchu and Chinese officials feared a return to the abuses of eunuch power that had plagued the late Ming.[115] Despite the emperor's attempt to impose strictures on eunuch activities, the Shunzhi Emperor's favorite eunuch Wu Liangfu (吳良輔; d. 1661), who had helped him defeat the Dorgon faction in the early 1650s, was caught in a corruption scandal in 1658.[116] The fact that Wu only received a reprimand for his accepting bribes did not reassure the Manchu elite, which saw eunuch power as a degradation of Manchu power.[117] The Thirteen Offices would be eliminated (and Wu Liangfu executed) by Oboi and the other regents of the Kangxi Emperor in March 1661 soon after the Shunzhi Emperor's death.[118]

Frontiers, tributaries, and foreign relations

In 1646, when Qing armies led by Bolo had entered the city of Fuzhou, they had found envoys from the Ryūkyū Kingdom, Annam, and the Spanish in Manila.[120] These tributary embassies that had come to see the now fallen Longwu Emperor of the Southern Ming were forwarded to Beijing, and eventually sent home with instructions about submitting to the Qing.[120] The King of the Ryūkyū Islands sent his first tribute mission to the Qing in 1649, Siam in 1652, and Annam in 1661, after the last remnants of Ming resistance had been removed from Yunnan, which bordered Annam.[120]

Also in 1646 sultan Abu al-Muhammad Haiji Khan, a Moghul prince who ruled Turfan, had sent an embassy requesting the resumption of trade with China, which had been interrupted by the fall of the Ming dynasty.[121] The mission was sent without solicitation, but the Qing agreed to receive it, allowing it to conduct tribute trade in Beijing and Lanzhou (Gansu).[122] But this agreement was interrupted by a Muslim rebellion that engulfed the northwest in 1646 (see the last paragraph of the "Conquest of China" section above). Tribute and trade with Hami and Turfan, which had aided the rebels, were eventually resumed in 1656.[123] In 1655, however, the Qing court announced that tributary missions from Turfan would be accepted only once every five years.[124]

In 1651 the young emperor invited to Beijing the Fifth Dalai Lama, the leader of the Yellow Hat Sect of Tibetan Buddhism, who, with the military help of Khoshot Mongol Gushri Khan, had recently unified religious and secular rule in Tibet.[125] Qing emperors had been patrons of Tibetan Buddhism since at least 1621 under the reign of Nurhaci, but there were also political reasons behind the invitation.[126] Namely, Tibet was becoming a powerful polity west of the Qing, and the Dalai Lama held influence over Mongol tribes, many of which had not submitted to the Qing.[127] To prepare for the arrival of this "living Buddha," the Shunzhi Emperor ordered the building of the White Dagoba (baita 白塔) on an island on one of the imperial lakes northwest of the Forbidden City, at the former site of Qubilai Khan's palace.[128] After more invitations and diplomatic exchanges to decide where the Tibetan leader would meet the Qing emperor, the Dalai Lama arrived in Beijing in January 1653.[lower-alpha 3] The Dalai Lama later had a scene of this visit carved in the Potala Palace in Lhasa, which he had started building in 1645.[129]

Meanwhile, north of the Manchu homeland, adventurers Vassili Poyarkov (1643–1646) and Yerofei Khabarov (1649–1653) had started to explore the Amur River valley for Tzarist Russia. In 1653 Khabarov was recalled to Moscow and replaced by Onufriy Stepanov, who assumed command of Khabarov's Cossack troops.[130] Stepanov went south into the Sungari River, along which he exacted "yasak" (fur tribute) from native populations such as the Daur and the Duchers, but these groups resisted because they were already paying tribute to the Shunzhi Emperor ("Shamshakan" in Russian sources).[131] In 1654 Stepanov defeated a small Manchu force that had been despatched from Ningguta to investigate Russian advances.[130] In 1655 another Qing commander, the Mongol Minggadari (d. 1669), defeated Stepanov's forces at fort Kumarsk on the Amur, but this was not enough to chase the Russians.[132] In 1658, however, Manchu general Šarhūda (1599–1659) attacked Stepanov with a fleet of 40 or more ships that managed to kill or capture most Russians.[130] This Qing victory temporarily cleared the Amur valley of Cossack bands, but Sino-Russian border conflicts would continue until 1689, when the signature of the Treaty of Nerchinsk fixed the borders between Russia and the Qing.[130]

Continuous campaigns against the Southern Ming

Though the Qing under Dorgon's leadership had successfully pushed the Southern Ming deep into southern China, Ming loyalism was not dead yet. In early August 1652, Li Dingguo, who had served as general in Sichuan under bandit king Zhang Xianzhong (d. 1647) and was now protecting the Yongli Emperor of the Southern Ming, retook Guilin (Guangxi province) from the Qing.[133] Within a month, most of the commanders who had been supporting the Qing in Guangxi reverted to the Ming side.[134] Despite occasionally successful military campaigns in Huguang and Guangdong in the next two years, Li failed to retake important cities.[133] In 1653, the Qing court put Hong Chengchou in charge of retaking the southwest.[135] Headquartered in Changsha (in what is now Hunan province), he patiently built up his forces; only in late 1658 did well-fed and well-supplied Qing troops mount a multipronged campaign to take Guizhou and Yunnan.[135] In late January 1659, a Qing army led by Manchu prince Doni took the capital of Yunnan, sending the Yongli Emperor fleeing into nearby Burma, which was then ruled by King Pindale Min of the Toungoo dynasty.[135] The last sovereign of the Southern Ming stayed there until 1662, when he was captured and executed by Wu Sangui, the former Ming general whose surrender to the Manchus in April 1644 had allowed Dorgon to start the Qing conquest of China.[136]

Zheng Chenggong ("Koxinga"), who had been adopted by the Longwu Emperor in 1646 and ennobled by Yongli in 1655, also continued to defend the cause of the Southern Ming.[137] In 1659, just as the Shunzhi Emperor was preparing to hold a special examination to celebrate the glories of his reign and the success of the southwestern campaigns, Zheng sailed up the Yangtze River with a well-armed fleet, took several cities from Qing hands, and went so far as to threaten Nanjing.[138] When the emperor heard of this sudden attack he is said to have slashed his throne with a sword in anger.[138] But the siege of Nanjing was relieved and Zheng Chenggong repelled, forcing Zheng to take refuge in the southeastern coastal province of Fujian.[139] Pressured by Qing fleets, Zheng fled to Taiwan in April 1661 but died that same summer.[140] His descendants resisted Qing rule until 1683, when the Kangxi Emperor successfully took the island.[141]

Personality and relationships

After Fulin came to rule on his own in 1651, his mother the Empress Dowager Xiaozhuang arranged for him to marry her niece, but the young monarch deposed his new Empress in 1653.[142] The following year Xiaozhuang arranged another imperial marriage with her Khorchin Mongol clan, this time matching her son with her own grand-niece.[142] Though Fulin also disliked his second empress (known posthumously as Empress Xiaohuizhang), he was not allowed to demote her. She never bore him children.[143] Starting in 1656, the Shunzhi Emperor lavished his affection on Consort Donggo, who, according to Jesuit accounts from the time, had first been the wife of another Manchu noble.[144] She gave birth to a son (the Shunzhi Emperor's fourth) in November 1657. The emperor would have made him his heir apparent, but he died early in 1658 before he was given a name.[145]

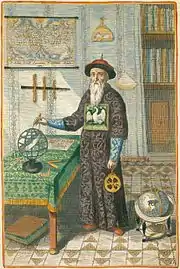

The Shunzhi Emperor was an open-minded emperor and relied on the advice of Johann Adam Schall von Bell, a Jesuit missionary from Cologne in the Germanic parts of the Holy Roman Empire, for guidance on matters ranging from astronomy and technology to religion and government.[146] In late 1644, Dorgon had put Schall in charge of preparing a new calendar because his eclipse predictions had proven more reliable than those of the official astronomer.[147] After Dorgon's death Schall developed a personal relationship with the young emperor, who called him "grandfather" (mafa in Manchu).[148] At the height of his influence in 1656 and 1657, Schall reports that the Shunzhi Emperor often visited his house and talked to him late into the night.[146] He was excused from prostrating himself in the presence of the emperor, was granted land to build a church in Beijing, and was even given imperial permission to adopt a son (because Fulin worried that Schall did not have an heir), but the Jesuits' hope of converting the Qing sovereign to Christianity was crushed when the Shunzhi Emperor became a devout follower of Chan Buddhism in 1657.[149]

The emperor developed a good command of Chinese that allowed him to manage matters of state and to appreciate Chinese arts such as calligraphy and drama.[150] One of his favorite texts was "Rhapsody of a Myriad Sorrows" (Wan chou qu 萬愁曲), by Gui Zhuang (歸莊; 1613–1673), who was a close friend of anti-Qing intellectuals Gu Yanwu and Wan Shouqi (萬壽祺; 1603–1652).[151] "Quite passionate and attach[ing] great importance to qing (love)," he could also recite by heart long passages of the popular Romance of the Western Chamber.[150]

Death and succession

Smallpox

In September 1660, Consort Donggo, the Shunzhi Emperor's favourite consort, suddenly died as a result of grief over the loss of a child.[138] Overwhelmed with grief, the emperor fell into dejection for months, until he contracted smallpox on 2 February 1661.[138] On 4 February 1661, officials Wang Xi (王熙, 1628–1703; the emperor's confidant) and Margi (a Manchu) were called to the emperor's bedside to record his last will.[152] On the same day, his seven-year-old third son Xuanye was chosen to be his successor, probably because he had already survived smallpox.[153] The emperor died on 5 February 1661 in the Forbidden City at the age of twenty-two.[138]

The Manchus feared smallpox more than any other disease because they had no immunity to it and almost always died when they contracted it.[154] By 1622 at the latest, they had already established an agency to investigate smallpox cases and isolate sufferers to avoid contagion.[155] During outbreaks, royal family members were routinely sent to "smallpox avoidance centers" (bidousuo 避痘所) to protect themselves from infection.[156] The Shunzhi Emperor was particularly fearful of the disease, because he was young and lived in a large city, near sources of contagion.[156] Indeed, during his reign at least nine outbreaks of smallpox were recorded in Beijing, each time forcing the emperor to move to a protected area such as the "Southern Park" (Nanyuan 南苑), a hunting ground south of Beijing where Dorgon had built a "smallpox avoidance center" in the 1640s.[157] Despite this and other precautions—such as rules forcing Chinese residents to move out of the city when they contracted smallpox—the young monarch still succumbed to that illness.[158]

Forged last will

The emperor's last will, which was made public on the evening of 5 February, appointed four regents for his young son: Oboi, Soni, Suksaha, and Ebilun, who had all helped Jirgalang to purge the court of Dorgon's supporters after Dorgon's death on the last day of 1650.[159] It is difficult to determine whether the Shunzhi Emperor had really named these four Manchu nobles as regents, because they and Empress Dowager Xiaozhuang clearly tampered with the emperor's testament before promulgating it.[lower-alpha 4] The emperor's will expressed his regret about his Chinese-style ruling (his reliance on eunuchs and his favoritism toward Chinese officials), his neglect of Manchu nobles and traditions, and his headstrong devotion to his consort rather than to his mother.[160] Though the emperor had often issued self-deprecating edicts during his reign, the policies his will rejected had been central to his government since he had assumed personal rule in the early 1650s.[161] The will as it was formulated gave "the mantle of imperial authority" to the four regents, and served to support their pro-Manchu policies during the period known as the Oboi regency, which lasted from 1661 to 1669.[162]

After death

Because court statements did not clearly announce the cause of the emperor's death, rumors soon started to circulate that he had not died but in fact retired to a Buddhist monastery to live anonymously as a monk, either out of grief for the death of his beloved consort, or because of a coup by the Manchu nobles his will had named as regents.[163] These rumors seemed not so incredible because the emperor had become a fervent follower of Chan Buddhism in the late 1650s, even letting monks move into the imperial palace.[164] Modern Chinese historians have considered the Shunzhi Emperor's possible retirement as one of the three mysterious cases of the early Qing.[lower-alpha 5] But much circumstantial evidence—including an account by one of these monks that the emperor's health greatly deteriorated in early February 1661 because of smallpox, and the fact that a concubine and an Imperial Bodyguard committed suicide to accompany the emperor in burial—suggests that the Shunzhi Emperor's death was not staged.[165]

After being kept in the Forbidden City for 27 days of mourning, on 3 March 1661 the emperor's corpse was transported in a lavish procession to Jingshan 景山 (a hillock just north of the Forbidden City), after which a large amount of precious goods were burned as funeral offerings.[166] Only two years later, in 1663, was the body transported to its final resting place.[167] Contrary to Manchu customs at the time, which usually dictated that a deceased person should be cremated, the Shunzhi Emperor was buried.[168] He was interred in what later came to be known as the Eastern Qing Tombs, 125 kilometers (75 miles) northeast of Beijing, one of two Qing imperial cemeteries.[169] His tomb is part of the Xiao (孝) mausoleum complex (known in Manchu as the Hiyoošungga Munggan), which was the first mausoleum to be erected on that site.[169]

Legacy

.jpg.webp)

The fake will in which the Shunzhi Emperor had supposedly expressed regret for abandoning Manchu traditions gave authority to the nativist policies of the Kangxi Emperor's four regents.[171] Citing the testament, Oboi and the other regents quickly abolished the Thirteen Eunuch Bureaus.[172] Over the next few years, they enhanced the power of the Imperial Household Department, which was run by Manchus and their bondservants, eliminated the Hanlin Academy, and limited membership in the Deliberative Council of Princes and Ministers to Manchus and Mongols.[173] The regents also adopted aggressive policies toward the Qing's Chinese subjects: they executed dozens of people and punished thousands of others in the wealthy Jiangnan region for literary dissent and tax arrears, and forced the coastal population of southeast China to move inland in order to starve the Taiwan-based Kingdom of Tungning run by descendants of Koxinga.[174]

After the Kangxi Emperor managed to imprison Oboi in 1669, he reverted many of the regents' policies.[175] He restored institutions his father had favored, including the Grand Secretariat, through which Chinese officials gained an important voice in government.[176] He also defeated the rebellion of the Three Feudatories, three Chinese military commanders who had played key military roles in the Qing conquest, but had now become entrenched rulers of enormous domains in southern China.[177] The civil war (1673–1681) tested the loyalty of the new Qing subjects, but Qing armies eventually prevailed.[178] Once victory had become certain, a special examination for "eminent scholars of broad learning" (Boxue hongru 博學鴻儒) was held in 1679 to attract Chinese literati who had refused to serve the new dynasty.[179] The successful candidates were assigned to compile the official history of the fallen Ming dynasty.[177] The rebellion was defeated in 1681, the same year the Kangxi Emperor initiated the use of variolation to inoculate children of the imperial family against smallpox.[180] When the Kingdom of Tungning finally fell in 1683, the military consolidation of the Qing regime was complete.[177] The institutional foundation laid by Dorgon, and the Shunzhi and Kangxi emperors allowed the Qing to erect an imperial edifice of awesome proportion and to turn it into "one of the most successful imperial states the world has known."[181] Ironically, however, the prolonged Pax Manchurica that followed the Kangxi consolidation made the Qing unprepared to face aggressive European powers with modern weaponry in the nineteenth century.[182]

Family

Although only nineteen empresses and consorts are recorded for the Shunzhi Emperor in the Aisin Gioro genealogy made by the Imperial Clan Court, burial records show that he had at least thirty-two of them.[183] Twelve bore him children. There were two empresses in his reign, both relatives of his mother the empress dowager. After the 1644 conquest, imperial consorts and empresses were usually known by their titles and by the name of their patrilineal clan.[184]

Eleven of the Shunzhi Emperor's 32 spouses bore him a total of fourteen children,[185] but only four sons (Fuquan, Xuanye, Changning, and Longxi) and one daughter (Princess Gongque) lived to be old enough to marry. Unlike later Qing emperors, the names of the Shunzhi Emperor's sons did not include a generational character.[186]

Before the Qing court moved to Beijing in 1644, Manchu women used to have personal names, but after 1644 these names "disappear from the genealogical and archival records."[184] Only after their betrothal were imperial daughters given a title and rank, by which they then became known.[184] Although five of the Shunzhi Emperor's six daughters died in infancy or childhood, they all appear in the Aisin Gioro genealogy.[184]

Empress

- Consort Jing, of the Khorchin Borjigit clan (靜妃 博爾濟吉特氏), first cousin, personal name Erdeni Bumba (額爾德尼布木巴)

- Empress Xiaohuizhang, of the Khorchin Borjigit clan (孝惠章皇后 博爾濟吉特氏; 5 November 1641 – 7 January 1718), personal name Alatan Qiqige (阿拉坦琪琪格)

- Empress Xiaoxian, of the Donggo clan (孝獻皇后 董鄂氏; 1639 – 23 September 1660)

- Prince Rong of the First Rank (榮親王; 12 November 1657 – 25 February 1658), fourth son

- Empress Xiaokangzhang, of the Tunggiya clan (孝康章皇后 佟佳氏; 1638 – 20 March 1663)

- Xuanye, the Kangxi Emperor (聖祖 玄燁; 4 May 1654 – 20 December 1722), third son

Consort

- Consort Dao, of the Khorchin Borjigit clan (悼妃 博爾濟吉特氏; d. 7 April 1658), first cousin

- Consort Zhen, of the Donggo clan (貞妃 董鄂氏; d. 5 February 1661)

- Consort Ke, of the Shi clan (恪妃 石氏; d. 13 January 1668)

- Consort Gongjing, of the Hotsit Borjigit clan (恭靖妃 博爾濟吉特氏; d. 20 May 1689)

- Consort Shuhui, of the Khorchin Borjigit clan (淑惠妃 博爾濟吉特氏; 1642 – 17 December 1713), first cousin once removed

- Consort Duanshun, of the Abaga Borjigit clan (端順妃 博爾濟吉特氏; d. 1 August 1709)

- Consort Ningque, of the Donggo clan (寧愨妃 董鄂氏; d. 11 August 1694)

- Fuquan, Prince Yuxian of the First Rank (裕憲親王 福全; 8 September 1653 – 10 August 1703), second son

Concubine

- Mistress, of the Ba clan (巴氏)

- Niuniu (牛鈕; 13 December 1651 – 9 March 1652), first son

- Third daughter (30 January 1654 – April/May 1658)

- Fifth daughter (6 February 1655 – January 1661)

- Mistress, of the Chen clan (陳氏; d. 1690)

- First daughter (22 April 1652 – November/December 1653)

- Changning, Prince Gong of the First Rank (恭親王 常寧; 8 December 1657 – 20 July 1703), fifth son

- Mistress, of the Yang clan (楊氏)

- Princess Gongque of the Second Rank (和碩恭愨公主; 19 January 1654 – 26 November 1685), second daughter

- Married Na'erdu (訥爾杜; d. 1676) of the Manchu Gūwalgiya clan in February/March 1667

- Fourth daughter (9 January 1655 – March/April 1661)

- Princess Gongque of the Second Rank (和碩恭愨公主; 19 January 1654 – 26 November 1685), second daughter

- Mistress, of the Nara clan (那拉氏)

- Sixth daughter (11 November 1657 – March 1661)

- Mistress, of the Tang clan (唐氏)

- Qishou (奇授; 3 January 1660 – 12 December 1665), sixth son

- Mistress, of the Niu clan (鈕氏)

- Longxi, Prince Chunjing of the First Rank (純靖親王 隆禧; 30 May 1660 – 20 August 1679), seventh son

- Mistress, of the Muktu clan (穆克圖氏)

- Yonggan (永幹; 23 January 1661 – 15 January 1668), eighth son

Ancestry

| Giocangga (1526–1583) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Taksi (1543–1583) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Empress Yi | |||||||||||||||||||

| Nurhaci (1559–1626) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Agu | |||||||||||||||||||

| Empress Xuan (d. 1569) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Hong Taiji (1592–1643) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Taitanju | |||||||||||||||||||

| Yangginu (d. 1583) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Empress Xiaocigao (1575–1603) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Mother-in-law of Yehe | |||||||||||||||||||

| Shunzhi Emperor (1638–1661) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Namusai | |||||||||||||||||||

| Manggusi | |||||||||||||||||||

| Jaisang | |||||||||||||||||||

| Empress Xiaozhuangwen (1613–1688) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Boli (d. 1654) | |||||||||||||||||||

In popular culture

- Portrayed by Jung Yoon-seok in the 2013 TV series Blooded Palace: The War of Flowers.

- Portrayed by an unknown voice actor in The Mr. Peabody & Sherman Show episode "Sherman Exchange Program".

See also

- Chinese emperors family tree (late)

- Chronology of the Shunzhi reign

- List of emperors of the Qing dynasty

Explanatory notes

- Dorgon's brother Dodo received the command to lead this "southern expedition" (nan zheng 南征) on 1 April.[58] He set out from Xi'an on that very day.[59] The Ming Prince of Fu had been crowned as emperor on 19 June 1644.[60][61]

- For examples of the factional struggles that weakened the Hongguang court, see Wakeman 1985, pp. 523–43. Some defections are explained in Wakeman 1985, pp. 543–45.

- Western historians do not seem to agree on the date of the Dalai Lama's visit: see Wakeman 1985, p. 929, note 81 ("1651"); Crossley 1999, p. 239 ("1651"); Naquin 2000, pp. 311 and 473 ("1652"); Benard 2004, p. 134, note 23 ("1652"); Zarrow 2004b, p. 187, note 5 ("between 1652 and 1653"); Rawski 1998, p. 252 ("1653"); Berger 2003, p. 57. The Qing Veritable Records (Shilu 實錄) cited on p. 476 of Li 2003, however, clearly indicate that the Dalai Lama arrived in Beijing on 14 January 1653 (on the 15th day of the last month of the 9th year of Shunzhi) and left the capital sometime in the second month of the 10th year of Shunzhi (March 1653).

- Historians agree that the Shunzhi Emperor's will was either deeply modified or forged altogether. See for instance Oxnam 1975, pp. 62–63 and 205-7; Kessler 1976, p. 20; Wakeman 1985, p. 1015; Dennerline 2002, p. 119; and Spence 2002, p. 126.

- See Meng Sen 孟森 (1868–1937), The Three Disputed Cases of the Early Qing 《清初三大疑案》 (1935) (in Chinese). The other two are whether Dorgon secretly married Empress Dowager Xiaozhuang and whether the Yongzheng Emperor usurped the succession to his father, the Kangxi Emperor.

References

Citations

- Wakeman 1985, p. 34.

- Roth Li 2002, pp. 25–26.

- Roth Li 2002, pp. 29–30 (campaigns of Jurchen unification) and 40 (seizing of patents).

- Roth Li 2002, p. 34.

- Roth Li 2002, p. 36.

- Roth Li 2002, p. 28.

- Roth Li 2002, p. 37.

- Roth Li 2002, p. 42.

- Roth Li 2002, p. 46.

- Roth Li 2002, p. 51.

- Elliott 2001, p. 63.

- Roth Li 2002, pp. 29–30.

- Roth Li 2002, p. 63.

- Elliott 2001, p. 64 (preparing to attack the Ming); Spence 1999, pp. 21–24 (late Ming crises).

- Oxnam 1975 (p. 38), Wakeman 1985 (p. 297), and Gong 2010 (p. 51) all place Hong Taiji's death on 21 September (Chongde 崇德 8.8.9). Dennerline 2002 (p. 74) gives the date as 9 September.

- Rawski 1998, p. 98.

- Rawski 1998, p. 99 (about the White and Yellow banners); Dennerline 2002, p. 79 (table with age of the imperial princes and the banners they controlled).

- Dennerline 2002, p. 77 (convening of the Deliberative Council to discuss Hong Taiji's succession); Hucker 1985, p. 266 (Deliberative Council as "the most influential shaper of policy in the early Ch'ing" [i.e., Qing]; Bartlett 1991, p. 1 (the Grand Council rose "to the overlordship of almost the entire central government of the Chinese empire" in the 1720s and 1730s).

- Dennerline 2002, p. 78.

- Fang 1943a, p. 255.

- Dennerline 2002, p. 73.

- Wakeman 1985, p. 299.

- Wakeman 1985, p. 300, note 231.

- Dennerline 2002, p. 79.

- Roth Li 2002, p. 71.

- Mote 1999, p. 809.

- Wakeman 1985, p. 304; Dennerline 2002, p. 81.

- Wakeman 1985, p. 290.

- Wakeman 1985, p. 304.

- Wakeman 1985, p. 308.

- Wakeman 1985, pp. 311–12.

- Wakeman 1985, p. 313; Mote 1999, p. 817.

- Wakeman 1985, p. 313.

- Wakeman 1985, p. 314 (were all expecting Wu and the heir apparent) and 315 (reaction to seeing Dorgon instead).

- Wakeman 1985, p. 315.

- Naquin 2000, p. 289.

- Mote 1999, p. 818.

- Wakeman 1985, p. 416; Mote 1999, p. 828.

- Wakeman 1985, pp. 420–22 (which explains these matters and claims that the order was repealed by edict on 25 June). Gong 2010, p. 84 gives the date as 28 June.

- Wakeman 1985, p. 857.

- Wakeman 1985, p. 858.

- Wakeman 1985, pp. 858 and 860 ("According to the emperor's speechwriter, who was probably Fan Wencheng, Dorgon even 'surpassed' (guo) the revered Duke of Zhou because 'The Uncle Prince also led the Grand Army through Shanhai Pass to smash two hundred thousand bandit soldiers, and then proceeded to take Yanjing, pacifying the Central Xia. He invited Us to come to the capital and received Us as a great guest'.").

- Wakeman 1985, pp. 860–61, and p. 861, note 31.

- Wakeman 1985, p. 861.

- Wakeman 1985, pp. 478–.

- See maps in Naquin 2000, p. 356 and Elliott 2001, p. 103.

- Oxnam 1975, p. 170.

- Wakeman 1985, p. 477 and Naquin 2000, pp. 289–91.

- Naquin 2000, p. 291.

- Elman 2002, p. 389.

- Cited in Elman 2002, pp. 389–90.

- Man-Cheong 2004, p. 7, Table 1.1 (number of graduates per session under each Qing reign); Wakeman 1985, p. 954 (reason for the high quotas); Elman 2001, p. 169 (lower quotas in 1660).

- Wang 2004, pp. 215–216 & 219–221.

- Walthall, Anne (1 January 2008). Servants of the Dynasty: Palace Women in World History. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-25444-2.

- Zarrow 2004a, passim.

- Wakeman 1985, pp. 483 (Li reestablished headquarters in Xi'an) and 501 (Hebei and Shandong revolts, new campaigns against Li).

- Wakeman 1985, pp. 501–7.

- Wakeman 1985, p. 521

- Struve 1988, p. 657

- Wakeman 1985, p. 346

- Struve 1988, p. 644

- Wakeman 1985, p. 522 (taking of Xuzhou; Struve 1988, p. 657 (converging on Yangzhou).

- Struve 1988, p. 657.

- Finnane 1993, p. 131.

- Struve 1988, p. 657 (purpose of the massacre was to terrorize Jiangnan); Zarrow 2004a, passim (late-Qing uses of the Yangzhou massacre).

- Struve 1988, p. 660.

- Struve 1988, p. 660 (capture of Suzhou and Hangzhou by early July 1645; new frontier); Wakeman 1985, p. 580 (capture of the emperor around 17 June, and later death in Beijing).

- Wakeman 1985, p. 647; Struve 1988, p. 662; Dennerline 2002, p. 87 (which calls this edict "the most untimely promulgation of [Dorgon's] career."

- Kuhn 1990, p. 12.

- Wakeman 1985, p. 647 ("From the Manchus' perspective, the command to cut one's hair or lose one's head not only brought rulers and subjects together into a single physical resemblance; it also provided them with a perfect loyalty test").

- Wakeman 1985, pp. 648–49 (officials and literati) and 650 (common men). In the Classic of Filial Piety, Confucius is cited to say that "a person's body and hair, being gifts from one's parents, are not to be damaged: this is the beginning of filial piety" (身體髮膚,受之父母,不敢毀傷,孝之始也). Prior to the Qing dynasty, adult Han Chinese men customarily did not cut their hair, but instead wore it in a topknot.

- Struve 1988, pp. 662–63 ("broke the momentum of the Qing conquest"); Wakeman 1975, p. 56 ("the hair-cutting order, more than any other act, engendered the Kiangnan [Jiangnan] resistance of 1645"); Wakeman 1985, p. 650 ("the rulers' effort to make Manchus and Han one unified 'body' initially had the effect of unifying upper- and lower-class natives in central and south China against the interlopers").

- Wakeman 1975, p. 78.

- Wakeman 1975, p. 83.

- Wakeman 1985, p. 674.

- Struve 1988, pp. 665 (on the Prince of Tang) and 666 (on the Prince of Lu).

- Struve 1988, pp. 667–69 (for their failure to cooperate), 669-74 (for the deep financial and tactical problems that beset both regimes).

- Struve 1988, p. 675.

- Struve 1988, p. 676.

- Wakeman 1985, p. 737.

- Wakeman 1985, p. 738.

- Wakeman 1985, pp. 765–66.

- Wakeman 1985, p. 767.

- Wakeman 1985, pp. 767–68.

- Dai 2009, p. 17.

- Dai 2009, pp. 17–18.

- Rossabi 1979, p. 191.

- Larsen & Numata 1943, p. 572 (Meng Qiaofang, death of rebel leaders); Rossabi 1979, p. 192.

- Oxnam 1975, p. 47 ("intense factional rivalry," "among the fiercest and most complex of the early Ch'ing"); Wakeman 1985, pp. 892–93 (date and cause of Dorgon's death) and 907 (second "great wave of Qing institutional reform" from 1652 to 1655).

- Oxnam 1975, pp. 47–48.

- Oxnam 1975, p. 47.

- Oxnam 1975, p. 48.

- Elliott 2001, p. 79 (Manchu name; "personal property of the emperor"); Oxnam 1975, p. 48 (timing and purpose of Jirgalang's move).

- Oxnam 1975, p. 49.

- Dennerline 2002, p. 106.

- Dennerline 2002, p. 107.

- Dennerline 2002, p. 106 (dismissal of Feng Quan in 1651); Wakeman 1985, pp. 865–72 (for the story of the failed purge of Feng Quan in 1645).

- Dennerline 2002, p. 107 ("coalition of literary societies"); Wakeman 1985, p. 865.

- Dennerline 2002, pp. 108–9.

- Dennerline 2002, p. 109.

- Wakeman 1985, p. 958.

- Wakeman 1985, pp. 959–74 (discussion of these cases).

- Wakeman 1985, pp. 976 (April 1654, Ning Wanwo) and 977–81 (long discussion of Chen Mingxia's "crimes").

- Wakeman 1985, pp. 985–86.

- Gong 2010, p. 295 gives the date as 30 November 1657.

- Wakeman 1985, p. 1004, note 38.

- Ho 1962, pp. 191–92.

- Wakeman 1985, pp. 1004–5.

- Dennerline 2002, pp. 109 (topics of discussions with Chen Mingxia) and 112 (on Wang Xi).

- Mair 1985, p. 326 ("bare bones"); Oxnam 1975, pp. 115–16.

- Dennerline 2002, p. 113.

- Wakeman 1985, p. 931 ("Thirteen Offices"); Rawski 1998, p. 163 ("Thirteen Eunuch Bureaus," supervised by Manchus).

- Dennerline 2002, p. 113; Oxnam 1975, pp. 52–53.

- Wakeman 1985, p. 931 (composed edicts); Oxnam 1975, p. 52.

- Oxnam 1975, p. 52 (isolated emperor from his officials); Kessler 1976, p. 27.

- Wakeman 1985, p. 1016; Kessler 1976, p. 27; Oxnam 1975, p. 54.

- Oxnam 1975, pp. 52–53.

- Kessler 1976, p. 27; Rawski 1998, p. 163 (specific date).

- In 1951 Italian scholar Luciano Petech was the first to hypothesize that these emissaries came from Turfan, not from the Moghul India (Petech 1951, pp. 124–27, cited in Lach & van Kley 1994, plate 315). Kim 2008, p. 109 discusses this Turfan embassy in some detail.

- Wills 1984, p. 40.

- Kim 2008, p. 109.

- Kim 2008, p. 109 ("without solicitation"; location of trade); Rossabi 1979, p. 190 (within the constraints of the old tributary system).

- Rossabi 1979, p. 192.

- Kim 2008, p. 111.

- Rawski 1998, p. 250 (unification or religious and secular rule).

- Rawski 1998, p. 251 (beginning of Qing patronage of Tibetan Buddhism).

- Zarrow 2004b, p. 187, note 5 (political reasons for inviting the Dalai Lama).

- Wakeman 1985, p. 929, note 81 (site of Qionghua Island and Qubilai's former palace); Naquin 2000, p. 309 (preparation for Lama's visit, "bell-shaped" temple).

- Naquin 2000, p. 473; Chayet 2004, p. 40 (date of the beginning of the construction of the Potala).

- Fang 1943b, p. 632.

- Turayev 1995.

- Kennedy 1943, p. 576 (Mongol); Fang 1943b, p. 632 (victory, but "yielded no permanent success").

- Struve 1988, p. 704.

- Wakeman 1985, p. 973, note 194.

- Dennerline 2002, p. 117.

- Struve 1988, p. 710.

- Spence 2002, p. 136.

- Dennerline 2002, p. 118.

- Wakeman 1985, pp. 1048–49.

- Spence 2002, pp. 136–37.

- Spence 2002, p. 146.

- Gates & Fang 1943, p. 300.

- Wu 1979, p. 36.

- Wu 1979, pp. 15–16.

- Wu 1979, p. 16.

- Spence 1969, p. 19.

- Oxnam 1975, p. 54; Wakeman 1985, p. 858, note 24.

- Spence 1969, p. 19; Wakeman 1985, p. 929, note 82.

- Spence 1969, p. 19 (list of privileges); Fang 1943a, p. 258 (date of conversion to Buddhism).

- Zhou 2009, pp. 12.

- Wakeman 1984, p. 631, note 2.

- Oxnam 1975, p. 205.

- Spence 2002, p. 125. Note that Xuanye was born in May 1654, and was therefore less than seven years old. Both Spence 2002 and Oxnam 1975 (p. 1) nonetheless claim that he was "seven years old." Dennerline 2002 (p. 119) and Rawski 1998 (p. 99) indicate that he was "not yet seven years old." In Chinese documents concerning the succession, Xuanye was said to be eight sui (Oxnam 1975, p. 62).

- Perdue 2005, p. 47 ("Seventy to 80 percent of those infected died"); Chang 2002, p. 196 (most feared disease among the Manchus).

- Chang 2002, p. 180.

- Chang 2002, p. 181.

- Naquin 2000, p. 311 (Southern Park used as hunting ground); Chang 2002, pp. 181 (number of outbreaks) and 192 (Dorgon building a bidousuo in the Southern Park).

- Naquin 2000, p. 296 (on rule forcing Chinese residents to move out).

- Oxnam 1975, pp. 48 (on the four men helping Jirgalang), 50 (date of promulgation of the edict of succession), and 62 (on appointment of the four regents); Kessler 1976, p. 21 (on helping to get rid of Dorgon's faction in the early 1650s).

- Oxnam 1975, p. 52.

- Oxnam 1975, p. 51 (on proclamations in which the emperor "publicly degraded himself") and 52 (on the centrality of these policies to the Shunzhi Emperor's rule).

- Oxnam 1975, p. 63.

- Spence 2002, p. 125.

- Fang 1943a, p. 258 (emperor became a devout Buddhist in 1657); Dennerline 2002, p. 118 (emperor had become devoted to Buddhism "by 1659"; monks living in the palace).

- Oxnam 1975, p. 205 (for monk's diary, citing an older study by Chinese historian Meng Sen 孟森); Spence 2002, p. 125 (on the two suicides).

- Standaert 2008, pp. 73–74.

- Standaert 2008, p. 75.

- Elliott 2001, p. 477, note 122 (citing several studies and primary documents). By contrast, Hong Taiji and the Shunzhi Emperor's two empresses had been cremated (Elliott 2001, p. 264).

- Fang 1943a, p. 258.

- Chang 2007, p. 86.

- Kessler 1976, p. 26; Oxnam 1975, p. 63.

- Oxnam 1975, p. 65.

- Oxnam 1975, p. 71 (details of membership in the Deliberative Council); Spence 2002, pp. 126–27 (other institutions).

- Kessler 1976, pp. 31–32 (Ming history case), 33–36 (tax arrears case), and 39–46 (clearing of the coast).

- Spence 2002, p. 133.

- Kessler 1976, p. 30 (restored in 1670).

- Spence 2002, p. 122.

- Spence 2002, pp. 140–43 (details of the campaigns).

- Li 2010, p. 153.

- Rawski 1998, p. 113 (use of variolation starting in 1681).

- Dennerline 2002, p. 73 (citation); Wakeman 1985, p. 1125 (institutional foundation, awesome proportion).

- Wakeman 1985, p. 1127.

- See table in Rawski 1998, p. 141.

- Rawski 1998, p. 129.

- See table in Rawski 1998, p. 142.

- See table in Rawski 1998, p. 112.

Works cited

- Main studies

- Dennerline, Jerry (2002), "The Shun-chih Reign", in Peterson, Willard J. (ed.), Cambridge History of China, Vol. 9, Part 1: The Ch'ing Dynasty to 1800, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 73–119, ISBN 0-521-24334-3.

- Fang, Chao-ying (1943). . In Hummel, Arthur W. Sr. (ed.). Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period. United States Government Printing Office. pp. 255–59.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Struve, Lynn (1988), "The Southern Ming", in Mote, Frederic W.; Twitchett, Denis; Fairbank, John King (eds.), Cambridge History of China, Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 641–725, ISBN 0-521-24332-7.

- Wakeman, Frederic (1985), The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-Century China, Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-04804-0. In two volumes.

- Other works

- Bartlett, Beatrice S. (1991), Monarchs and Ministers: The Grand Council in Mid-Ch'ing China, 1723–1820, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-08645-7.

- Benard, Elisabeth (2004), "The Qianlong emperor and Tibetan Buddhism", in Millward, James A.; et al. (eds.), New Qing Imperial History: The Making of Inner Asian Empire at Qing Chengde, London and New York: RoutledgeCurzon, pp. 123–35, ISBN 0-415-32006-2.

- Berger, Patricia (2003), Empire of Emptiness: Buddhist Art and Political Authority in Qing China, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, ISBN 0-8248-2563-2.

- Chang, Chia-feng (2002), "Disease and its Impact on Politics, Diplomacy, and the Military: The Case of Smallpox and the Manchus (1613–1795)", Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 57 (2): 177–97, doi:10.1093/jhmas/57.2.177, PMID 11995595.

- Chang, Michael G. (2007), A Court on Horseback: Imperial Touring and the Construction of Qing Rule, 1680–1785, Cambridge (Mass.) and London: Harvard University Asia Center, ISBN 978-0-674-02454-0.

- Chayet, Anne (2004), "Architectural wonderland: an empire of fictions", in Millward, James A.; et al. (eds.), New Qing Imperial History: The making of Inner Asian empire at Qing Chengde, London and New York: RoutledgeCurzon, pp. 33–52, ISBN 0-415-32006-2.

- Crossley, Pamela Kyle (1999), A Translucent Mirror: History and Identity in Qing Imperial Ideology, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-21566-4.

- Dai, Yingcong (2009), The Sichuan Frontier and Tibet: Imperial Strategy in the Early Qing, Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, ISBN 978-0-295-98952-5.

- Elliott, Mark C. (2001), The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China, Stanford: Stanford University Press, ISBN 0-8047-4684-2.

- Elman, Benjamin A. (2001), A Cultural History of Civil Examinations in Late Imperial China, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-21509-5.

- Elman, Benjamin A. (2002), "The Social Roles of Literati in Early to Mid-Ch'ing", in Peterson, Willard J. (ed.), Cambridge History of China, Vol. 9, Part 1: The Ch'ing Dynasty to 1800, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 360–427, ISBN 0-521-24334-3.

- Fang, Chao-ying (1943). . In Hummel, Arthur W. Sr. (ed.). Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period. United States Government Printing Office. p. 632.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Finnane, Antonia (1993), "Yangzhou: A Central Place in the Qing Empire", in Cooke Johnson, Linda (ed.), Cities of Jiangnan in Late Imperial China, Albany, NY: SUNY Press, pp. 117–50, ISBN 0-7914-1423-X.

- Gates, M. Jean; Fang, Chao-ying (1943). . In Hummel, Arthur W. Sr. (ed.). Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period. United States Government Printing Office. pp. 300–1.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Gong, Baoli 宫宝利 (2010), Shunzhi shidian 顺治事典 ["Events of the Shunzhi reign"] (in Chinese), Beijing: Zijincheng chubanshe 紫禁城出版社 ["Forbidden City Press"], ISBN 978-7-5134-0018-3.

- Ho, Ping-ti (1962), The Ladder of Success in Imperial China: Aspects of Social Mobility, 1368–1911, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 0-231-05161-1.

- Hucker, Charles O. (1985), A Dictionary of Official Titles in Imperial China, Stanford: Stanford University Press, ISBN 0-8047-1193-3.

- Kennedy, George A. (1943). . In Hummel, Arthur W. Sr. (ed.). Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period. United States Government Printing Office. p. 576.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Kessler, Lawrence D. (1976), K'ang-hsi and the Consolidation of Ch'ing Rule, 1661–1684, Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-43203-3.

- Kim, Kwangmin (2008), Saintly brokers: Uyghur Muslims, trade, and the making of Central Asia, 1696–1814, PhD diss., History Department, University of California, Berkeley, ISBN 978-1-109-10126-3.

- Kuhn, Philip A. (1990), Soulstealers: The Chinese Sorcery Scare of 1768, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-82152-1.

- Lach, Donald F.; van Kley, Edwin J. (1994), Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume III, A Century of Advance, Book Four, East Asia, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-46734-4.

- Larsen, E. S.; Numata, Tomoo (1943). . In Hummel, Arthur W. Sr. (ed.). Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period. United States Government Printing Office. p. 572.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Li, Wai-yee (2010), "Early Qing to 1723", in Kang-i Sun Chang; Stephen Owen (eds.), The Cambridge History of Chinese Literature, Volume II: From 1375, Cambridge University Press, pp. 152–244, ISBN 978-0-521-11677-0 (2-volume set).

- Li, Zhiting 李治亭, ed. (2003), Qingchao tongshi: Shunzhi fenjuan 清朝通史: 順治分卷 [General History of the Qing Dynasty: Shunzhi Volume] (in Chinese), Beijing: Zijincheng chubanshe 紫禁城出版社 ["Fordidden City Press"], ISBN 7-80047-380-5.

- Mair, Victor H. (1985), "Language and Ideology in the Written Popularization of the Sacred Edict", in Johnson, David; et al. (eds.), Popular Culture in Late Imperial China, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, pp. 325–59, ISBN 0-520-06172-1.

- Man-Cheong, Iona D. (2004), The Class of 1761: Examinations, State, and Elites in Eighteenth-Century China, Stanford: Stanford University Press, ISBN 0-8047-4146-8.

- Mote, Frederick W. (1999), Imperial China, 900–1800, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-44515-5.

- Naquin, Susan (2000), Peking: Temples and City Life, 1400–1900, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-21991-0.

- Oxnam, Robert B. (1975), Ruling from Horseback: Manchu Politics in the Oboi Regency, 1661–1669, Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-64244-5.

- Perdue, Peter C. (2005), China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-01684-X.

- Petech, Luciano (1951), "La pretesa ambasciata di Shah Jahan alla Cina ["The alleged ambassy of Shah Jahan to China"]", Rivista degli studi orientali ["Review of Oriental Studies"] (in Italian), XXVI: 124–27.

- (in Chinese) Qingshi gao 清史稿 ["Draft History of Qing"]. Edited by Zhao Erxun 趙爾巽 et al. Completed in 1927. Citing 1976–77 edition by Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, in 48 volumes with continuous pagination.

- Rawski, Evelyn S. (1998), The Last Emperors: A Social History of Qing Imperial Institutions, Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-22837-5.

- Rossabi, Morris (1979), "Muslim and Central Asian Revolts", in Spence, Jonathan D.; Wills, John E. Jr. (eds.), From Ming to Ch'ing: Conquest, Region, and Continuity in Seventeenth-Century China, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, pp. 167–99, ISBN 0-300-02672-2.

- Roth Li, Gertraude (2002), "State Building Before 1644", in Peterson, Willard J. (ed.), Cambridge History of China, Vol. 9, Part 1:The Ch'ing Dynasty to 1800, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 9–72, ISBN 0-521-24334-3.

- Spence, Jonathan D. (1969), To Change China: Western Advisors in China, 1620–1960, Boston: Little, Brown & Company, ISBN 0-14-005528-2.

- Spence, Jonathan D. (1999), The Search for Modern China, New York: W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 0-393-97351-4.

- Spence, Jonathan D. (2002), "The K'ang-hsi Reign", in Peterson, Willard J. (ed.), Cambridge History of China, Vol. 9, Part 1: The Ch'ing Dynasty to 1800, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 120–82, ISBN 0-521-24334-3.

- Standaert, Nicolas (2008), The Interweaving of Rituals: Funerals in the Cultural Exchange Between China and Europe, Seattle: University of Washington Press, ISBN 978-0-295-98810-8.

- Turayev, Vadim [Вадим Тураев] (1995), "О ХАРАКТЕРЕ КУПЮР В ПУБЛИКАЦИЯХ ДОКУМЕНТОВ РУССКИХ ЗЕМЛЕПРОХОДЦЕВ XVII ["Regarding omissions in the publication of documents by seventeenth-century Russian explorers"]", in A.R. Artemyev (ed.), Русские первопроходцы на Дальнем Востоке в XVII – XIX вв. (Историко-археологические исследования) ["Russian pioneers in the Far East in the 17th–19th centuries: historical and archaeological research"], volume 2 (in Russian), Vladivostok: Rossiĭskaia akademiia nauk, Dalʹnevostochnoe otd-nie, ISBN 5-7442-0402-4.

- Wakeman, Frederic (1975), "Localism and Loyalism During the Ch'ing Conquest of Kiangnan: The Tragedy of Chiang-yin", in Wakeman, Frederic Jr.; Grant, Carolyn (eds.), Conflict and Control in Late Imperial China, Berkeley: Center of Chinese Studies, University of California, Berkeley, pp. 43–85, ISBN 0-520-02597-0.

- Wakeman, Frederic (1984), "Romantics, Stoics, and Martyrs in Seventeenth-Century China", Journal of Asian Studies, 43 (4): 631–65, doi:10.2307/2057148, JSTOR 2057148, S2CID 163314256.

- Wills, John E. (1984), Embassies and Illusions: Dutch and Portuguese Envoys to K'ang-hsi, 1666–1687, Cambridge (Mass.) and London: Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-24776-0.

- Wu, Silas H. L. (1979), Passage to Power: K'ang-hsi and His Heir Apparent, 1661–1722, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-65625-3.

- Zarrow, Peter (2004a), "Historical Trauma: Anti-Manchuism and Memories of Atrocity in Late Qing China", History and Memory, 16 (2): 67–107, doi:10.1353/ham.2004.0013, S2CID 161270740.

- Zarrow, Peter (2004b), "Qianlong's inscription on the founding of the Temple of the Happiness and Longevity of Mt Sumeru (Xumifushou miao)", in Millward, James A.; et al. (eds.), New Qing Imperial History: The Making of Inner Asian Empire at Qing Chengde, translated by Zarrow, London and New York: RoutledgeCurzon, pp. 185–87, ISBN 0-415-32006-2.

- Zhao, Gang (January 2006). "Reinventing China Imperial Qing Ideology and the Rise of Modern Chinese National Identity in the Early Twentieth Century". Modern China. Sage Publications. 32 (1): 3–30. doi:10.1177/0097700405282349. JSTOR 20062627. S2CID 144587815.

- Zhou, Ruchang [周汝昌] (2009), Between Noble and Humble: Cao Xueqin and the Dream of the Red Chamber, edited by Ronald R. Gray and Mark S. Ferrara, translated by Liangmei Bao and Kyongsook Park, New York: Peter Lang, ISBN 978-1-4331-0407-7.

External links

Media related to Shunzhi Emperor at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Shunzhi Emperor at Wikimedia Commons

.svg.png.webp)