Shortwave radio

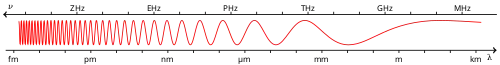

Shortwave radio is radio transmission using shortwave (SW) radio frequencies. There is no official definition of the band, but the range always includes all of the high frequency band (HF), which extends from 3 to 30 MHz (100 to 10 metres); above the medium frequency band (MF), to the bottom of the VHF band.

Radio waves in the shortwave band can be reflected or refracted from a layer of electrically charged atoms in the atmosphere called the ionosphere. Therefore, short waves directed at an angle into the sky can be reflected back to Earth at great distances, beyond the horizon. This is called skywave or "skip" propagation. Thus shortwave radio can be used for communication over very long distances, in contrast to radio waves of higher frequency, which travel in straight lines (line-of-sight propagation) and are limited by the visual horizon, about 64 km (40 miles).

Shortwave broadcasts of radio programs played an important role in the early days of radio history. In World War II it was used as a propaganda tool for an international audience. The heyday of international shortwave broadcasting was during the Cold War between 1960 and 1980.

With the wide implementation of other technologies for the distribution of radio programs, such as satellite radio and cable broadcasting as well as IP-based transmissions, shortwave broadcasting lost importance. Initiatives for the digitization of broadcasting did not bear fruit either, and so as of 2022, few broadcasters continue to broadcast programs on shortwave.

However, shortwave remains important in war zones, such as in the Russo-Ukrainian war, and shortwave broadcasts can be transmitted over thousands of miles from a single transmitter, making it difficult for government authorities to censor them.

History

Development

The name "shortwave" originated during the beginning of radio in the early 20th century, when the radio spectrum was divided into long wave (LW), medium wave (MW), and short wave (SW) bands based on the length of the wave. Shortwave radio received its name because the wavelengths in this band are shorter than 200 m (1,500 kHz) which marked the original upper limit of the medium frequency band first used for radio communications. The broadcast medium wave band now extends above the 200 m / 1,500 kHz limit.

Early long-distance radio telegraphy used long waves, below 300 kilohertz (kHz). The drawbacks to this system included a very limited spectrum available for long-distance communication, and the very expensive transmitters, receivers and gigantic antennas. Long waves are also difficult to beam directionally, resulting in a major loss of power over long distances. Prior to the 1920s, the shortwave frequencies above 1.5 MHz were regarded as useless for long-distance communication and were designated in many countries for amateur use.[2]

Guglielmo Marconi, pioneer of radio, commissioned his assistant Charles Samuel Franklin to carry out a large-scale study into the transmission characteristics of short-wavelength waves and to determine their suitability for long-distance transmissions. Franklin rigged up a large antenna at Poldhu Wireless Station, Cornwall, running on 25 kW of power. In June and July 1923, wireless transmissions were completed during nights on 97 meters (about 3 MHz) from Poldhu to Marconi's yacht Elettra in the Cape Verde Islands.[3]

In September 1924, Marconi arranged for transmissions to be made day and night on 32 meters (9.4& MHz) from Poldhu to his yacht in the harbour at Beirut, to which he had sailed, and was "astonished" to find he could receive signals "throughout the day".[4] Franklin went on to refine the directional transmission by inventing the curtain array aerial system.[5][6] In July 1924, Marconi entered into contracts with the British General Post Office (GPO) to install high-speed shortwave telegraphy circuits from London to Australia, India, South Africa and Canada as the main element of the Imperial Wireless Chain. The UK-to-Canada shortwave "Beam Wireless Service" went into commercial operation on 25 October 1926. Beam Wireless Services from the UK to Australia, South Africa and India went into service in 1927.[3]

Shortwave communications began to grow rapidly in the 1920s.[7] By 1928, more than half of long-distance communications had moved from transoceanic cables and longwave wireless services to shortwave, and the overall volume of transoceanic shortwave communications had vastly increased. Shortwave stations had cost and efficiency advantages over massive longwave wireless installations.[8] However, some commercial longwave communications stations remained in use until the 1960s. Long-distance radio circuits also reduced the need for new cables, although the cables maintained their advantages of high security and a much more reliable and better-quality signal than shortwave.

The cable companies began to lose large sums of money in 1927. A serious financial crisis threatened viability of cable companies that were vital to strategic British interests. The British government convened the Imperial Wireless and Cable Conference[9] in 1928 "to examine the situation that had arisen as a result of the competition of Beam Wireless with the Cable Services". It recommended and received government approval for all overseas cable and wireless resources of the Empire to be merged into one system controlled by a newly formed company in 1929, Imperial and International Communications Ltd. The name of the company was changed to Cable and Wireless Ltd. in 1934.

A resurgence of long-distance cables began in 1956 with the laying of TAT-1 across the Atlantic Ocean, the first voice frequency cable on this route. This provided 36 high-quality telephone channels and was soon followed by even higher-capacity cables all around the world. Competition from these cables soon ended the economic viability of shortwave radio for commercial communication.

Amateur use of shortwave propagation

Amateur radio operators also discovered that long-distance communication was possible on shortwave bands. Early long-distance services used surface wave propagation at very low frequencies,[10] which are attenuated along the path at wavelengths shorter than 1,000 meters. Longer distances and higher frequencies using this method meant more signal loss. This, and the difficulties of generating and detecting higher frequencies, made discovery of shortwave propagation difficult for commercial services.

Radio amateurs may have conducted the first successful transatlantic tests in December 1921,[11] operating in the 200 meter mediumwave band (near 1,500 kHz, inside the modern AM broadcast band), which at that time was the shortest wavelength / highest frequency available to amateur radio. In 1922 hundreds of North American amateurs were heard in Europe on 200 meters and at least 20 North American amateurs heard amateur signals from Europe. The first two-way communications between North American and Hawaiian amateurs began in 1922 at 200 meters. Although operation on wavelengths shorter than 200 meters was technically illegal (but tolerated at the time as the authorities mistakenly believed that such frequencies were useless for commercial or military use), amateurs began to experiment with those wavelengths using newly available vacuum tubes shortly after World War I.

Extreme interference at the longer edge of the 150–200 meter band – the official wavelengths allocated to amateurs by the Second National Radio Conference[12] in 1923 – forced amateurs to shift to shorter and shorter wavelengths; however, amateurs were limited by regulation to wavelengths longer than 150 meters (2 MHz). A few fortunate amateurs who obtained special permission for experimental communications at wavelengths shorter than 150 meters completed hundreds of long-distance two-way contacts on 100 meters (3 MHz) in 1923 including the first transatlantic two-way contacts.[13]

By 1924 many additional specially licensed amateurs were routinely making transoceanic contacts at distances of 6,000 miles (9,600 km) and more. On 21 September 1924 several amateurs in California completed two-way contacts with an amateur in New Zealand. On 19 October amateurs in New Zealand and England completed a 90 minute two-way contact nearly halfway around the world. On 10 October the Third National Radio Conference made three shortwave bands available to U.S. amateurs[14] at 80 meters (3.75 MHz), 40 meters (7 MHz) and 20 meters (14 MHz). These were allocated worldwide, while the 10 meter band (28 MHz) was created by the Washington International Radiotelegraph Conference[15] on 25 November 1927. The 15 meter band (21 MHz) was opened to amateurs in the United States on 1 May 1952.

Propagation characteristics

Shortwave radio frequency energy is capable of reaching any location on the Earth as it is influenced by ionospheric reflection back to the earth by the ionosphere, (a phenomenon known as "skywave propagation"). A typical phenomenon of shortwave propagation is the occurrence of a skip zone where reception fails. With a fixed working frequency, large changes in ionospheric conditions may create skip zones at night.

As a result of the multi-layer structure of the ionosphere, propagation often simultaneously occurs on different paths, scattered by the ‘E’ or ‘F’ layer and with different numbers of hops, a phenomenon that may be disturbed for certain techniques. Particularly for lower frequencies of the shortwave band, absorption of radio frequency energy in the lowest ionospheric layer, the ‘D’ layer, may impose a serious limit. This is due to collisions of electrons with neutral molecules, absorbing some of a radio frequency's energy and converting it to heat.[16] Predictions of skywave propagation depend on:

- The distance from the transmitter to the target receiver.

- Time of day. During the day, frequencies higher than approximately 12 MHz can travel longer distances than lower ones. At night, this property is reversed.

- With lower frequencies the dependence on the time of the day is mainly due to the lowest ionospheric layer, the ‘D’ Layer, forming only during the day when photons from the sun break up atoms into ions and free electrons.

- Season. During the winter months of the Northern or Southern hemispheres, the AM/MW broadcast band tends to be more favorable because of longer hours of darkness.

- Solar flares produce a large increase in D region ionization – so great, sometimes for periods of several minutes, that skywave propagation is nonexistent.

Types of modulation

Several different types of modulation are used to incorporate information in a short-wave signal.

AM

Amplitude modulation is the simplest type and the most commonly used for shortwave broadcasting. The instantaneous amplitude of the carrier is controlled by the amplitude of the signal (speech, or music, for example). At the receiver, a simple detector recovers the desired modulation signal from the carrier.[18]

SSB

Single-sideband transmission is a form of amplitude modulation but in effect filters the result of modulation. An amplitude-modulated signal has frequency components both above and below the carrier frequency. If one set of these components is eliminated as well as the residual carrier, only the remaining set is transmitted. This reduces power in the transmission, as roughly 2⁄3 of the energy sent by an AM signal is in the carrier, which is not needed to recover the information contained in the signal. It also reduces signal bandwidth, enabling less than one-half the AM signal bandwidth to be used.[18]

The drawback is the receiver is more complicated, since it must re-create the carrier to recover the signal. Small errors in the detection process greatly affect the pitch of the received signal. As a result, single sideband is not used for music or general broadcast. Single sideband is used for long-range voice communications by ships and aircraft, citizen's band, and amateur radio operators. Lower sideband (LSB) is customarily used below 9 MHz and USB (upper sideband) above 9 MHz.

VSB

Vestigial sideband transmits the carrier and one complete sideband, but filters out most of the other sideband. It is a compromise between AM and SSB, enabling simple receivers to be used, but requires almost as much transmitter power as AM. Its main advantage is that only half the bandwidth of an AM signal is used. It is used by the Canadian standard time signal station CHU. Vestigial sideband was used for analog television and by ATSC, the digital TV system used in North America.

NFM

Narrow-band frequency modulation (NBFM or NFM) is used typically above 20 MHz. Because of the larger bandwidth required, NBFM is commonly used for VHF communication. Regulations limit the bandwidth of a signal transmitted in the HF bands, and the advantages of frequency modulation are greatest if the FM signal has a wide bandwidth. NBFM is limited to short-range transmissions due to the multiphasic distortions created by the ionosphere.[19]

DRM

Digital Radio Mondiale (DRM) is a digital modulation for use on bands below 30 MHz. It is a digital signal, like the data modes, below, but is for transmitting audio, like the analog modes above.

CW

Continuous wave (CW) is on-and-off keying of a sine-wave carrier, used for Morse code communications and Hellschreiber facsimile-based teleprinter transmissions. It is a data mode, although often listed separately.[20] It is typically received via lower or upper SSB modes.[18]

RTTY, FAX, SSTV

Radioteletype, fax, digital, slow-scan television, and other systems use forms of frequency-shift keying or audio subcarriers on a shortwave carrier. These generally require special equipment to decode, such as software on a computer equipped with a sound card.

Note that on modern computer-driven systems, digital modes are typically sent by coupling a computer's sound output to the SSB input of a radio.

Users

Some established users of the shortwave radio bands may include:

- International broadcasting primarily by government-sponsored propaganda, or international news (for example, the BBC World Service) or cultural stations to foreign audiences: The most common use of all.

- Domestic broadcasting: to widely dispersed populations with few longwave, mediumwave and FM stations serving them; or for speciality political, religious and alternative media networks; or of individual commercial and non-commercial paid broadcasts.

- Oceanic air traffic control uses the HF/shortwave band for long-distance communication to aircraft over the oceans and poles, which are far beyond the range of traditional VHF frequencies. Modern systems also include satellite communications, such as ADS-C/CPDLC.

- Two-way radio communications by marine and maritime HF stations, aeronautical users, and ground based stations.[21] For example, two way shortwave communication is still used in remote regions by the Royal Flying Doctor Service of Australia.[22]

- "Utility" stations transmitting messages not intended for the general public, such as merchant shipping, marine weather, and ship-to-shore stations; for aviation weather and air-to-ground communications; for military communications; for long-distance governmental purposes, and for other non-broadcast communications.

- Amateur radio operators at the 80/75, 60, 40, 30, 20, 17, 15, 12, and 10 meter bands. Licenses are granted by authorized government agencies.

- Time signal and radio clock stations: In North America, WWV radio and WWVH radio transmit at these frequencies: 2.5 MHz, 5 MHz, 10 MHz, and 15 MHz; and WWV also transmits on 20 MHz. The CHU radio station in Canada transmits on the following frequencies: 3.33 MHz, 7.85 MHz, and 14.67 MHz. Other similar radio clock stations transmit on various shortwave and longwave frequencies around the world. The shortwave transmissions are primarily intended for human reception, while the longwave stations are generally used for automatic synchronization of watches and clocks.

Sporadic or non-traditional users of the shortwave bands may include:

- Clandestine stations. These are stations that broadcast on behalf of various political movements such as rebel or insurrectionist forces. They may advocate civil war, insurrection, rebellion against the government-in-charge of the country to which they are directed. Clandestine broadcasts may emanate from transmitters located in rebel-controlled territory or from outside the country entirely, using another country's transmission facilities.[23]

- Numbers stations. These stations regularly appear and disappear all over the shortwave radio band, but are unlicensed and untraceable. It is believed that numbers stations are operated by government agencies and are used to communicate with clandestine operatives working within foreign countries. However, no definitive proof of such use has emerged. Because the vast majority of these broadcasts contain nothing but the recitation of blocks of numbers, in various languages, with occasional bursts of music, they have become known colloquially as "number stations". Perhaps the most noted number station is called the "Lincolnshire Poacher", named after the 18th century English folk song, which is transmitted just before the sequences of numbers.

- Unlicensed two way radio activity by individuals such as taxi drivers, bus drivers and fishermen in various countries can be heard on various shortwave frequencies. Such unlicensed transmissions by "pirate" or "bootleg" two way radio operators[24] can often cause signal interference to licensed stations. Unlicensed business radio (taxis, trucking companies, among numerous others) land mobile systems may be found in the 20-30 MHz region while unlicensed marine mobile and other similar users may be found over the entire shortwave range.[25]

- Pirate radio broadcasters who feature programming such as music, talk and other entertainment, can be heard sporadically and in various modes on the shortwave bands. Pirate broadcasters take advantage of the better propagation characteristics to achieve more range compared to the AM or FM broadcast bands.[26]

- Over-the-horizon radar: From 1976 to 1989, the Soviet Union's Russian Woodpecker over-the-horizon radar system blotted out numerous shortwave broadcasts daily.

- Ionospheric heaters used for scientific experimentation such as the High Frequency Active Auroral Research Program in Alaska, and the Sura ionospheric heating facility in Russia.[27]

Shortwave broadcasting

- See International broadcasting for details on the history and practice of broadcasting to foreign audiences.

- See List of shortwave radio broadcasters for a list of international and domestic shortwave radio broadcasters.

- See Shortwave relay station for the actual kinds of integrated technologies used to bring high power signals to listeners.

Frequency allocations

The World Radiocommunication Conference (WRC), organized under the auspices of the International Telecommunication Union, allocates bands for various services in conferences every few years. The last WRC took place in 2019.[28]

At WRC-97 in 1997, the following bands were allocated for international broadcasting. AM shortwave broadcasting channels are allocated with a 5 kHz separation for traditional analog audio broadcasting.

| Metre Band | Frequency Range | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| 120 m | 2.3–2.495 MHz | tropical band |

| 90 m | 3.2–3.4 MHz | tropical band |

| 75 m | 3.9–4 MHz | shared with the North American amateur radio 80m band |

| 60 m | 4.75–5.06 MHz | tropical band |

| 49 m | 5.9–6.2 MHz | |

| 41 m | 7.2–7.6 MHz | shared with the amateur radio 40m band |

| 31 m | 9.4–9.9 MHz | currently the most heavily used band |

| 25 m | 11.6–12.2 MHz | |

| 22 m | 13.57–13.87 MHz | |

| 19 m | 15.1–15.8 MHz | |

| 16 m | 17.48–17.9 MHz | |

| 15 m | 18.9–19.02 MHz | almost unused, could become a DRM band |

| 13 m | 21.45–21.85 MHz | |

| 11 m | 25.6–26.1 MHz | may be used for local DRM broadcasting |

Although countries generally follow the table above, there may be small differences between countries or regions. For example, in the official bandplan of the Netherlands,[29] the 49 m band starts at 5.95 MHz, the 41 m band ends at 7.45 MHz, the 11 m band starts at 25.67 MHz, and the 120 m, 90 m, and 60 m bands are absent altogether. Additionally, international broadcasters sometimes operate outside the normal WRC-allocated bands or use off-channel frequencies. This is done for practical reasons, or to attract attention in crowded bands (60 m, 49 m, 40 m, 41 m, 31 m, 25 m).

The new digital audio broadcasting format for shortwave DRM operates 10 kHz or 20 kHz channels. There are some ongoing discussions with respect to specific band allocation for DRM, as it mainly transmitted in 10 kHz format.

The power used by shortwave transmitters ranges from less than one watt for some experimental and amateur radio transmissions to 500 kilowatts and higher for intercontinental broadcasters and over-the-horizon radar. Shortwave transmitting centers often use specialized antenna designs (like the ALLISS antenna technology) to concentrate radio energy at the target area.

Advantages

Shortwave does possess a number of advantages over newer technologies, including the following:

- Difficulty of censoring programming by authorities in restrictive countries. Unlike their relative ease in monitoring and censoring the Internet, government authorities face technical difficulties monitoring which stations (sites) are being listened to (accessed). For example, during the attempted coup against Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev, when his access to communications was limited (e.g. his phones were cut off, etc.), Gorbachev was able to stay informed by means of the BBC World Service on shortwave.[30]

- Low-cost shortwave radios are widely available in all but the most repressive countries in the world. Simple shortwave regenerative receivers can be easily built with a few parts.

- In many countries (particularly in most developing nations and in the Eastern bloc during the Cold War era) ownership of shortwave receivers has been and continues to be widespread[31] (in many of these countries some domestic stations also used shortwave).

- Many newer shortwave receivers are portable and can be battery-operated, making them useful in difficult circumstances. Newer technology includes hand-cranked radios which provide power without batteries.

- Shortwave radios can be used in situations where Internet or satellite communications service is temporarily, long-term or permanently unavailable (or unaffordable).

- Shortwave radio travels much farther than broadcast FM (88–108 MHz). Shortwave broadcasts can be easily transmitted over a distance of several thousand miles, including from one continent to another.

- Particularly in tropical regions, SW is somewhat less prone to interference from thunderstorms than medium wave radio, and is able to cover a large geographic area with relatively low power (and hence cost). Therefore, in many of these countries it is widely used for domestic broadcasting.

- Very little infrastructure is required for long-distance two-way communications using shortwave radio. All one needs is a pair of transceivers, each with an antenna, and a source of energy (such as a battery, a portable generator, or the electrical grid). This makes shortwave radio one of the most robust means of communications, which can be disrupted only by interference or bad ionospheric conditions. Modern digital transmission modes such as MFSK and Olivia are even more robust, allowing successful reception of signals well below the noise floor of a conventional receiver.

Disadvantages

Shortwave radio's benefits are sometimes regarded as being outweighed by its drawbacks, including:

- In most Western countries, shortwave radio ownership is usually limited to true enthusiasts, since most new standard radios do not receive the shortwave band. Therefore, Western audiences are limited.

- In the developed world, shortwave reception is very difficult in urban areas because of excessive noise from switched-mode power adapters, fluorescent or LED light sources, internet modems and routers, computers and many other sources of radio interference.

- Audio quality may be limited due to interference and the modes that are used.

Shortwave listening

The Asia-Pacific Telecommunity estimates that there are approximately 600 million shortwave broadcast-radio receivers in use in 2002.[32] WWCR claims that there are 1.5 billion shortwave receivers worldwide.[33]

Many hobbyists listen to shortwave broadcasters. In some cases, the goal is to hear as many stations from as many countries as possible (DXing); others listen to specialized shortwave utility, or "ute", transmissions such as maritime, naval, aviation, or military signals. Others focus on intelligence signals from numbers stations, stations which transmit strange broadcast usually for intelligence operations, or the two way communications by amateur radio operators. Some short wave listeners behave analogously to "lurkers" on the Internet, in that they listen only, and never attempt to send out their own signals. Other listeners participate in clubs, or actively send and receive QSL cards, or become involved with amateur radio and start transmitting on their own.

Many listeners tune the shortwave bands for the programmes of stations broadcasting to a general audience (such as Radio Taiwan International, China Radio International, Voice of America, Radio France Internationale, BBC World Service, Voice of Korea, Radio Free Sarawak etc.). Today, through the evolution of the Internet, the hobbyist can listen to shortwave signals via remotely controlled or web controlled shortwave receivers around the world, even without owning a shortwave radio.[34] Many international broadcasters offer live streaming audio on their websites and a number have closed their shortwave service entirely, or severely curtailed it, in favour of internet transmission.[35]

Shortwave listeners, or SWLs, can obtain QSL cards from broadcasters, utility stations or amateur radio operators as trophies of the hobby. Some stations even give out special certificates, pennants, stickers and other tokens and promotional materials to shortwave listeners.

Shortwave broadcasts and music

Some musicians have been attracted to the unique aural characteristics of shortwave radio which – due to the nature of amplitude modulation, varying propagation conditions, and the presence of interference – generally has lower fidelity than local broadcasts (particularly via FM stations). Shortwave transmissions often have bursts of distortion, and "hollow" sounding loss of clarity at certain aural frequencies, altering the harmonics of natural sound and creating at times a strange "spacey" quality due to echoes and phase distortion. Evocations of shortwave reception distortions have been incorporated into rock and classical compositions, by means of delays or feedback loops, equalizers, or even playing shortwave radios as live instruments. Snippets of broadcasts have been mixed into electronic sound collages and live musical instruments, by means of analogue tape loops or digital samples. Sometimes the sounds of instruments and existing musical recordings are altered by remixing or equalizing, with various distortions added, to replicate the garbled effects of shortwave radio reception.[36][37]

The first attempts by serious composers to incorporate radio effects into music may be those of the Russian physicist and musician Léon Theremin,[38] who perfected a form of radio oscillator as a musical instrument in 1928 (regenerative circuits in radios of the time were prone to breaking into oscillation, adding various tonal harmonics to music and speech); and in the same year, the development of a French instrument called the Ondes Martenot by its inventor Maurice Martenot, a French cellist and former wireless telegrapher. Karlheinz Stockhausen used shortwave radio and effects in works including Hymnen (1966–1967), Kurzwellen (1968) – adapted for the Beethoven Bicentennial in Opus 1970 with filtered and distorted snippets of Beethoven pieces – Spiral (1968), Pole, Expo (both 1969–1970), and Michaelion (1997).[36]

Cypriot composer Yannis Kyriakides incorporated shortwave numbers station transmissions in his 1999 ConSPIracy cantata.[39]

Holger Czukay, a student of Stockhausen, was one of the first to use shortwave in a rock music context.[37] In 1975, German electronic music band Kraftwerk recorded a full length concept album around simulated radiowave and shortwave sounds, entitled Radio-Activity.[40] The The's Radio Cineola monthly broadcasts drew heavily on shortwave radio sound.[41]

Shortwave's future

The development of direct broadcasts from satellites has reduced the demand for shortwave receiver hardware, but there are still a great number of shortwave broadcasters. A new digital radio technology, Digital Radio Mondiale (DRM), is expected to improve the quality of shortwave audio from very poor to standards comparable to the FM broadcast band.[42][43] The future of shortwave radio is threatened by the rise of power line communication (PLC), also known as Broadband over Power Lines (BPL), which uses a data stream transmitted over unshielded power lines. As the BPL frequencies used overlap with shortwave bands, severe distortions can make listening to analog shortwave radio signals near power lines difficult or impossible.[44]

According to Andy Sennitt, former editor of the World Radio TV Handbook,

shortwave is a legacy technology, which is expensive and environmentally unfriendly. A few countries are hanging on to it, but most have faced up to the fact that the glory days of shortwave have gone. Religious broadcasters will still use it because they are not too concerned with listening figures.[42]

However, Thomas Witherspoon, editor of shortwave news site SWLingPost.com wrote that

shortwave remains the most accessible international communications medium that still provides listeners with the protection of complete anonymity.[45]

In 2018, Nigel Fry, head of Distribution for the BBC World Service Group,

I still see a place for shortwave in the 21st century, especially for reaching areas of the world that are prone to natural disasters that destroy local broadcasting and Internet infrastructure.[42]

During the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the BBC World Service launched two new shortwave frequencies for listeners in Ukraine and Russia, broadcasting English-language news updates in an effort to avoid censorship by the Russian state.[46]

See also

- ALLISS–a very large rotatable antenna system used in international broadcasting

- List of American shortwave broadcasters

- List of European short wave transmitters

- List of shortwave radio broadcasters

References

- "Grundig Satellit 400 international / professional". ShortWaveRadio.ch. Archived from the original on 13 February 2018. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- Nebeker, Frederik (6 May 2009). Dawn of the Electronic Age: Electrical Technologies in the Shaping of the Modern World, 1914 to 1945. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 157 ff. ISBN 978-0-470-40974-9. Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- Bray, John (2002). Innovation and the Communications Revolution: From the Victorian pioneers to broadband Internet. IET. pp. 73–75. ISBN 9780852962183. Archived from the original on 29 April 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- Marconi, Degna (1996) [1962]. My Father, Marconi. Toronto / New York: Edizione Frassinelli. p. 207. ISBN 1-55071-044-3.

- Beauchamp, K.G. (2001). History of Telegraphy. IET. p. 234. ISBN 0-85296-792-6. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 23 November 2007.

- Burns, R.W. (1986). British Television: The formative years. IET. p. 315. ISBN 0-86341-079-0. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 23 November 2007.

- Beyond the Ionosphere: Fifty years of satellite communication (full text). 1997. ISBN 9780160490545. Retrieved 31 August 2012 – via Archive.org.

- Hugill, Peter J. (4 March 1999). Global Communications Since 1844: Geopolitics and technology. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 129 ff. ISBN 978-0-8018-6074-4. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- "Cable and wireless PLC history". Archived from the original on 20 March 2015.

- "Marconi wireless on Cape Cod". Stormfax.com. Archived from the original on 2008-10-24. Retrieved 2009-05-24.

- "1921 – Club station 1BCG and the transatlantic tests". Radio Club of America. Archived from the original on 7 November 2009. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- "Radio Service Bulletin No. 72". Bureau of Navigation. Department of Commerce. 2 April 1923. pp. 9–13. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help) - Raide, Bob, W2ZM; Gable, Ed, K2MP (2 November 1998). "Celebrating the first trans-Atlantic QSO!". Newington, CT: American Radio Relay League. Archived from the original on 30 November 2009.

- Frequency or wave band allocations. Recommendations for Regulation of Radio Adopted by the Third National Radio Conference. 6–10 October 1924. p. 15. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- Continelli, Bill, W2XOY (1996). "Article #8". twiar.org. The Wayback Machine. Schenectady Museum Amateur Radio Club. Archived from the original on 10 June 2007. Retrieved 2 July 2007. Historical note discusses an International Radiotelegraph Conference on 4 October 1927, its intrigues and fallout.

- Rawer, Karl (1993). Wave Propagation in the Ionosphere. Dordrecht: Kluwer. ISBN 0-7923-0775-5.

- "Panasonic / National". ShortwaveRadio.ch. Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- Rohde, Ulrich L.; Whitaker, Jerry (6 December 2000). Communications Receivers: DSP, software radios, and design (third ed.). New York, NY: McGraw Hill Professional. ISBN 0-07-136121-9. ISBN 978-007-136121-7

- Sinclair, Ian Robertson (2000). Audio and Hi-Fi Handbook. Newnes. pp. 195–196. ISBN 0-7506-4975-5.

- "Feld Hell Club". Google Sites. Archived from the original on 10 January 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- Ilčev, Stojče Dimov (10 December 2019). Global Aeronautical Distress and Safety Systems (GADSS): Theory and Applications. Springer Nature. ISBN 9783030306328. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- Berg, Jerome S. (20 September 2013). The Early Shortwave Stations: A Broadcasting History Through 1945. McFarland. ISBN 9780786474110. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- Sterling, Christopher H. (March 2004). Encyclopedia of Radio. Routledge. pp. 538 ff. ISBN 978-1-135-45649-8. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- Popular Mechanics. Hearst Magazines. January 1940. pp. 62 ff. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- "IARU Monitoring System". iaru.org. International Amateur Radio Union (IARU). Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- Yoder, Andrew R. (2002). Pirate Radio Stations: Tuning in to underground broadcasts in the Air and Online. McGraw Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-137563-4. Archived from the original on 2020-08-19. Retrieved 2017-11-28.

- Bychkov, Vladimir; Golubkov, Gennady; Nikitin, Anatoly (17 July 2010). The Atmosphere and Ionosphere: Dynamics, processes and monitoring. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 104 ff. ISBN 978-90-481-3212-6. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- "World Radiocommunication Conference 2019 (WRC-19), Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, 28 October to 22 November 2019". Itu.int. Retrieved 2022-03-16.

- "Nationaal Frequentieplan". rijksoverheid.nl. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- "dxld7078". w4uvh.net. Archived from the original on 9 April 2010. Retrieved 2009-10-21.

- Habrat, Marek. "Odbiornik "Roksana"" [Radio constructor's recollections]. Archived from the original on 6 June 2009. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- "[no title cited]". aptsec.org. Archived from the original on 10 February 2005.

- Anderson, Arlyn T. (2005). "Changes at the BBC World Service: Documenting the World Service's move from shortwave to web radio in North America, Australia, and New Zealand". Journal of Radio Studies. 12 (2): 286–304. doi:10.1207/s15506843jrs1202_8. S2CID 154174203. cited in "WWCR FAQ". Archived from the original on 14 November 2006. Retrieved 8 February 2007.

- "Live tunable receivers". The Radio Reference Wiki. Archived from the original on 2020-01-02. Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- "Whatever Happened to Shortwave Radio?". Radio World. 2010-03-08. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

- Wörner, Karl Heinrich (1973). Stockhausen: Life and work. University of California Press. pp. 76 ff. ISBN 978-0-520-02143-3. Archived from the original on 18 August 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- Sheppard, David (1 May 2009). On Some Faraway Beach: The life and times of Brian Eno. Chicago Review Press. pp. 275 ff. ISBN 978-1-55652-107-2. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- The Wire. C. Parker. 2000. Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- Dolp, Laura (13 July 2017). Arvo Pärt's White Light. Cambridge University Press. pp. 83 ff. ISBN 978-1-107-18289-9. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- Barr, Tim (31 August 2013). Kraftwerk: From Dusseldorf to the future with love. Ebury Publishing. pp. 98 ff. ISBN 978-1-4481-7776-9. Archived from the original on 18 August 2020. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- "Radio Cineola". thethe.com. Archived from the original on 18 December 2011.

- Careless, James. "The evolution of shortwave radio". Radio World. NewBay Media. Archived from the original on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- Amaral, Cristiano Torres (2021). Guia Moderno do Radioescuta. Amazon.

- Hrasnica, Halid; Haidine, Abdelfatteh; Lehnert, Ralf (14 January 2005). Broadband Powerline Communications: Network design. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 34 ff. ISBN 978-0-470-85742-7. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- Witherspoon, Thomas. "[no title cited]". SWLingPost.com.

- "Millions of Russians turn to BBC News". BBC. Archived from the original on 4 March 2022. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

External links

- "A beginner's guide to shortwave radio listening". SWLing.com.

- Hauser, Glenn. "World of Radio".

- "Space Weather and Radio Propagation Center". propagation.hfradio.org. View live and historical data and images of space weather and radio propagation.

- "Short-wave radio, snap and crackle goes pop. Life in the old wireless yet". The Economist. article describing pros and cons of short wave radio since the Cold War.

- "Short-wave radio telephone is success in tests". Popular Mechanics. Hearst Magazines. July 1931. mid page 114. describes experiments carried out for the French and British governments.

- "Que Escuchar en la Onda Corta en Español". queescucharenlaoc.blogspot.com (in Spanish).