Simultaneous game

In game theory, a simultaneous game or static game[1] is a game where each player chooses their action without knowledge of the actions chosen by other players.[2] Simultaneous games contrast with sequential games, which are played by the players taking turns (moves alternate between players). In other words, both players normally act at the same time in a simultaneous game. Even if the players do not act at the same time, both players are uninformed of each other's move while making their decisions.[3] Normal form representations are usually used for simultaneous games.[4] Given a continuous game, players will have different information sets if the game is simultaneous than if it is sequential because they have less information to act on at each step in the game. For example, in a two player continuous game that is sequential, the second player can act in response to the action taken by the first player. However, this is not possible in a simultaneous game where both players act at the same time.

Characteristics

In sequential games, players observe what rivals have done in the past and there is a specific order of play.[5] However, in simultaneous games, all players select strategies without observing the choices of their rivals and players choose at the exact same time.[5]

A simple example is rock-paper-scissors in which all players make their choice at the exact same time. However moving at exactly the same time isn’t always taken literally, instead players may move without being able to see the choices of other players.[5] A simple example is an election in which not all voters will vote literally at the same time but each voter will vote not knowing what anyone else has chosen.

Given that decision makers are rational, then so is individual rationality. An outcome is individually rational if it yields each player at least his security level.[6] The security level for Player i is the amount max min Hi (s) that the player can guarantee themselves unilaterally, that is, without considering the actions of other players.

Representation

In a simultaneous game, players will make their moves simultaneously, determine the outcome of the game and receive their payoffs.

The most common representation of a simultaneous game is normal form (matrix form). For a 2 player game; one player selects a row and the other player selects a column at the exact same time. Traditionally, within a cell, the first entry is the payoff of the row player, the second entry is the payoff of the column player. The “cell” that is chosen is the outcome of the game.[4] To determine which "cell" is chosen, the payoffs for both the row player and the column player must be compared respectively. Each player is best off where their payoff is higher.

Rock–paper–scissors, a widely played hand game, is an example of a simultaneous game. Both players make a decision without knowledge of the opponent's decision, and reveal their hands at the same time. There are two players in this game and each of them has three different strategies to make their decision; the combination of strategy profiles (a complete set of each player's possible strategies) forms a 3×3 table. We will display Player 1's strategies as rows and Player 2's strategies as columns. In the table, the numbers in red represent the payoff to Player 1, the numbers in blue represent the payoff to Player 2. Hence, the pay off for a 2 player game in rock-paper-scissors will look like this:[4]

Player 2 Player 1 |

Rock | Paper | Scissors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rock | 0 0 |

1 -1 |

-1 1 |

| Paper | -1 1 |

0 0 |

1 -1 |

| Scissors | 1 -1 |

-1 1 |

0 0 |

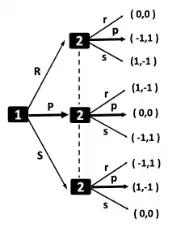

Another common representation of a simultaneous game is extensive form (game tree). Information sets are used to emphasize the imperfect information. Although it is not simple, it is easier to use game trees for games with more than 2 players.[4]

Even though simultaneous games are typically represented in normal form, they can be represented using extensive form too. While in extensive form one player’s decision must be draw before that of the other, by definition such representation does not correspond to the real life timing of the players’ decisions in a simultaneous game. The key to modeling simultaneous games in the extensive form is to get the information sets right. A dashed line between nodes in extensive form representation of a game represents information asymmetry and specifies that, during the game, a party cannot distinguish between the nodes,[7] due to the party being unaware of the other party's decision (by definition of "simultaneous game").

Some variants of chess that belong to this class of games include synchronous chess and parity chess.[8]

Bimatrix Game

In a simultaneous game, players only have one move and all players' moves are made simultaneously. The number of players in a game must be stipulated and all possible moves for each player must be listed. Each player may have different roles and options for moves.[9] However, each player has a finite number of options available to choose.

Two Players

An example of a simultaneous 2-player game:

A town has two companies, A and B, who currently make $8,000,000 each and need to determine whether they should advertise. The table below shows the payoff patterns; the rows are options of A and the columns are options of B. The entries are payoffs for A and B, respectively, separated by a comma.[9]

| B advertises | B doesn’t advertise | |

| A advertises | 2,2 | 5,1 |

| A doesn’t advertise | 1,5 | 8,8 |

Two Players (zero sum)

A zero-sum game is when the sum of payoffs equals zero for any outcome i.e. the losers pay for the winners gains. For a zero-sum 2-player game the payoff of player A doesn’t have to be displayed since it is the negative of the payoff of player B.[9]

An example of a simultaneous zero-sum 2-player game:

Rock–paper–scissors is being played by two friends, A and B for $10. The first cell stands for a payoff of 0 for both players. The second cell is a payoff of 10 for A which has to be paid by B, therefore a payoff of -10 for B.

| Rock | Paper | Scissors | |

| Rock | 0 |

−10 |

10 |

| Paper | 10 |

0 |

−10 |

| Scissors | −10 |

10 |

0 |

Three or more Players

An example of a simultaneous 3-player game:

A classroom vote is held as to whether or not they should have an increased amount of free time. Player A selects the matrix, player B selects the row, and player C selects the column.[9] The payoffs are:

| A votes for extra free time | ||

| C votes for extra free time | C votes against extra free time | |

| B votes for extra free time | 1,1,1 | 1,1,2 |

| B votes against extra free time | 1,2,1 | -1,0,0 |

| A votes against extra free time | ||

| C votes for extra free time | C votes against extra free time | |

| B votes for extra free time | 2,1,1 | 0,-1,0 |

| B votes against extra free time | 0,0,-1 | 0,0,0 |

Symmetric Games

All of the above examples have been symmetric. All players have the same options so if players interchange their moves, they also interchange their payoffs. By design, symmetric games are fair in which every player is given the same chances.[9]

Strategies - The Best Choice

Game theory should provide players with advice on how to find which move is best. These are known as “Best Response” strategies.[10]

Pure vs Mixed Strategy

Pure strategies are those in which players pick only one strategy from their best response. A Pure Strategy determines all your possible moves in a game, it is a complete plan for a player in a given game. Mixed strategies are those in which players randomize strategies in their best responses set. These have associated probabilities with each set of strategies. [10]

For simultaneous games, players will typically select mixed strategies while very occasionally choosing pure strategies. The reason for this is that in a game where players don’t know what the other one will choose it is best to pick the option that is likely to give the you the greatest benefit for the lowest risk given the other player could choose anything[10] i.e. if you pick your best option but the other player also picks their best option, someone will suffer.

Dominant vs Dominated Strategy

A dominant strategy provides a player with the highest possible payoff for any strategy of the other players. In simultaneous games, the best move a player can make is to follow their dominant strategy, if one exists.[11]

When analyzing a simultaneous game:

Firstly, identify any dominant strategies for all players. If each player has a dominant strategy, then players will play that strategy however if there is more than one dominant strategy then any of them are possible.[11]

Secondly, if there aren’t any dominant strategies, identify all strategies dominated by other strategies. Then eliminate the dominated strategies and the remaining are strategies players will play.[11]

Maximin Strategy

Some people always expect the worst and believe that others want to bring them down when in fact others want to maximise their payoffs. Still, nonetheless, player A will concentrate on their smallest possible payoff, believing this is what player A will get, they will choose the option with the highest value. This option is the maximin move (strategy), as it maximises the minimum possible payoff. Thus, the player can be assured a payoff of at least the maximin value, regardless of how the others are playing. The player doesn’t have the know the payoffs of the other players in order to choose the maximin move, therefore players can choose the maximin strategy in a simultaneous game regardless of what the other players choose.[10]

Nash Equilibrium

A pure Nash Equilibrium is when no one can gain a higher payoff by deviating from their move, provided others stick with their original choices. Nash equilibria are self-enforcing contracts, in which negotiation happens prior to the game being played in which each player best sticks with their negotiated move. In a Nash Equilibrium, each player is best responded to the choices of the other player. [11]

Prisoner's Dilemma

The prisoner’s dilemma originated with Merrill Flood and Melvin Dresher and is one of the most famous games in Game theory. The game is usually presented as follows:

Two members of a criminal gang have been apprehended by the police. Both individuals now sit in solitary confinement. The prosecutors have the evidence required to put both prisoners away on lesser charges. However, they do not possess the evidence required to convict the prisoners on their principle charges. The prosecution therefore simultaneously offers both prisoners a deal where they can choose to cooperate with one another by remaining silent, or they can choose betrayal, meaning they testify against their partner and receive a reduced sentence. It should be mentioned that the prisoners cannot communicate with one another. [12] Therefore, resulting in the following payoff matrix:

| Prisoner B

Prisoner A |

Prisoner B stays silent

(Cooperation) |

Prisoner B Confess

(Betrayal) |

|---|---|---|

| Prisoner A stays silent

(Cooperation) |

Each serves 1 Year | Prisoner A: 3 Years

Prisoner B: 3 Months |

| Prisoner A Confess

(Betrayal) |

Prisoner A: 3 Months

Prisoner B: 3 Years |

Each serves 2 Years |

This game results in a clear dominant strategy of betrayal where the only strong Nash Equilibrium is for both prisoners to confess. This is because we assume both prisoners to be rational and possessing no loyalty towards one another. Therefore, betrayal provides a greater reward for a majority of the potential outcomes.[12] If B cooperates, A should choose betrayal, as serving 3 months is better than serving 1 year. Moreover, if B chooses betrayal, then A should also choose betrayal as serving 2 years is better than serving 3. The choice to cooperate clearly provides a better outcome for the two prisoners however from a perspective of self interest this option would be deemed irrational. The aforementioned both cooperating option features the least total time spent in prison, serving 2 years total. This total is significantly less than the Nash Equilibrium total, where both cooperate, of 4 years. However, given the constraints that Prisoners A and B are individually motivated, they will always choose betrayal. They do so by selecting the best option for themselves while considering each possible decisions of the other prisoner.

Battle of the Sexes

In the battle of the sexes game, a wife and husband decide independently whether to go to a football game or the ballet. Each person likes to do something together with the other, but the husband prefers football and the wife prefers ballet. The two Nash equilibria, and therefore the best responses for both husband and wife, are for them to both pick the same leisure activity e.g. (ballet, ballet) or (football, football).[11] The table below shows the payoff for each option:

| Football | Ballet | |

| Football | 3,2 | 1,1 |

| Ballet | 0,0 | 2,3 |

Socially Desirable Outcomes

Simultaneous games are designed to inform strategic choices in competitive and non cooperative environments. However, is important to note that Nash equilibria and many of the aforementioned strategies generally fail to result in socially desirable outcomes.

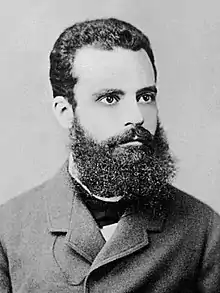

Pareto Optimality

Pareto efficiency is a notion rooted in the theoretical construct of perfect competition. Originating with Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto the concept refers to a state in which an economy has maximized efficiency in terms of resource allocation. Pareto Efficiency is closely linked to Pareto Optimality which is an ideal of Welfare Economics and often implies a notion of ethical consideration. A simultaneous game, for example, is said to reach Pareto optimality if there is no alternative outcome that can make at least one player better off while leaving all other players at least as well off. Therefore, these outcomes are referred to as socially desirable outcomes. [13]

The Stag Hunt

The Stag Hunt by philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau is a simultaneous game in which there are two players. The decision to be made is whether or not each player wishes to hunt a Stag or a Hare. Naturally hunting a Stag will provide greater utility in comparison to hunting a Hare. However, in order to hunt a Stag both players need to work together. On the other hand, each player is perfectly capable of hunting a hare alone. The resulting dilemma is that neither player can be sure of what the other will choose to do. Thus, providing the potential for a player to receive no payoff should they be the only party to choose to hunt a Stag. [14] Therefore, resulting in the following payoff matrix:

| Stag | Hare | |

| Stag | 3,3 | 0,1 |

| Hare | 1,0 | 1,1 |

The game is designed to illustrate a clear Pareto optimality where both players cooperate to hunt a Stag. However, due to the inherent risk of the game, such an outcome does not always come to fruition. It is imperative to note that Pareto optimality is not a strategic solution for simultaneous games. However, the ideal informs players about the potential for more efficient outcomes. Moreover, potentially providing insight into how players should learn to play over time. [15]

See also

- Sequential game

- Simultaneous action selection

References

- Pepall, Lynne, 1952- (2014-01-28). Industrial organization : contemporary theory and empirical applications. Richards, Daniel Jay., Norman, George, 1946- (Fifth ed.). Hoboken, NJ. ISBN 978-1-118-25030-3. OCLC 788246625.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - http://www-bcf.usc.edu The Path to Equilibrium in Sequential and Simultaneous Games (Brocas, Carrillo, Sachdeva; 2016).

- Managerial Economics: 3 edition. McGraw Hill Education (India) Private Limited. 2018. ISBN 978-93-87067-63-9.

- Mailath, G., Samuelson, L. and Swinkels, J., 1993. Extensive Form Reasoning in Normal Form Games. Econometrica, [online] 61(2), pp.273-278. Available at: <https://www.jstor.org/stable/2951552> [Accessed 30 October 2020].

- Sun, C., 2019. Simultaneous and Sequential Choice in a Symmetric Two‐Player Game with Canyon‐Shaped Payoffs. Japanese Economic Review, [online] Available at: <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332377544_Simultaneous_and_Sequential_Choice_in_a_Symmetric_Two-Player_Game_with_Canyon-Shaped_Payoffs> [Accessed 30 October 2020].

- "U-M Weblogin". weblogin.umich.edu. doi:10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5. Retrieved 2021-11-20.

- Watson, Joel. (2013-05-09). Strategy : an introduction to game theory (Third ed.). New York. ISBN 978-0-393-91838-0. OCLC 842323069.

- A V, Murali (2014-10-07). "Parity Chess". Blogger. Retrieved 2017-01-15.

- Prisner, E., 2014. Game Theory Through Examples. Mathematical Association of America Inc. [online] Switzerland: The Mathematical Association of America, pp.25-30. Available at: <https://www.maa.org/sites/default/files/pdf/ebooks/GTE_sample.pdf> [Accessed 30 October 2020].

- Ross, D., 2019. Game Theory. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, [online] pp.7-80. Available at: <https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/game-theory> [Accessed 30 October 2020].

- Munoz-Garcia, F. and Toro-Gonzalez, D., 2016. Pure Strategy Nash Equilibrium and Simultaneous-Move Games with Complete Information. Strategy and Game Theory, [online] pp.25-60. Available at: <https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-32963-5_2> [Accessed 30 October 2020].

- M., Amadae, S. (2016). Prisoners of reason : game theory and neoliberal political economy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-67119-5. OCLC 946968759.

- Berthonnet, Irène; Delclite, Thomas (2014-10-10), "Pareto-Optimality or Pareto-Efficiency: Same Concept, Different Names? An Analysis Over a Century of Economic Literature", A Research Annual, Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp. 129–145, ISBN 978-1-78441-154-1, retrieved 2021-04-25

- Vanderschraaf, Peter (2016). "In a Weakly Dominated Strategy Is Strength: Evolution of Optimality in Stag Hunt Augmented with a Punishment Option". Philosophy of Science. 83 (1): 29–59. doi:10.1086/684166. ISSN 0031-8248.

- Hao, Jianye; Leung, Ho-Fung (2013). "Achieving Socially Optimal Outcomes in Multiagent Systems with Reinforcement Social Learning". ACM Transactions on Autonomous and Adaptive Systems. 8 (3): 1–23. doi:10.1145/2517329. ISSN 1556-4665.

Bibliography

- Pritchard, D. B. (2007). Beasley, John (ed.). The Classified Encyclopedia of Chess Variants. John Beasley. ISBN 978-0-9555168-0-1.

.jpg.webp)