Steve Prefontaine

Steve Roland[1] "Pre" Prefontaine (January 25, 1951 – May 30, 1975) was an American long-distance runner who from 1973 to 1975 set American records at every distance from 2,000 to 10,000 meters.[2][3] He competed in the 1972 Summer Olympics,[4] and was preparing for the 1976 Olympics with the Oregon Track Club at the time of his death in 1975. Prefontaine's career, alongside those of Jim Ryun, Frank Shorter, and Bill Rodgers, generated considerable media coverage, which helped inspire the 1970s "running boom."[5][6] He died at age 24 in an automobile crash near his residence in Eugene, Oregon. One of the premier track meets in the world, the Prefontaine Classic, is held annually in Eugene in his honor. Prefontaine's celebrity and charisma later resulted in two 1990s feature films about his short life.

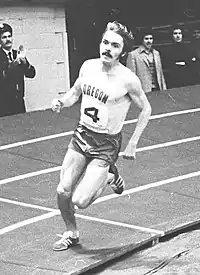

Prefontaine in 1973 | |||||||||||

| Personal information | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nationality | American | ||||||||||

| Born | January 25, 1951 Coos Bay, Oregon | ||||||||||

| Died | May 30, 1975 (aged 24) Eugene, Oregon | ||||||||||

| Height | 5 ft 9 in (1.75 m) | ||||||||||

| Weight | 152 lb (69 kg) | ||||||||||

| Sport | |||||||||||

| Country | |||||||||||

| Sport | Athletics/Track, Long-distance running | ||||||||||

| Event(s) | 5000 meters, 10,000 meters, mile, 2 mile | ||||||||||

| College team | Oregon Ducks | ||||||||||

| Club | Oregon Track Club | ||||||||||

| Coached by | Bill Bowerman | ||||||||||

| Achievements and titles | |||||||||||

| Olympic finals | 1972 Munich 5000 m, 4th | ||||||||||

| Personal best(s) | |||||||||||

Medal record

| |||||||||||

Early life

Prefontaine was born on January 25, 1951, in Coos Bay, Oregon.[7] His father, Raymond George Prefontaine (November 11, 1919 – December 21, 2004), was a welder who served in the U.S. Army in World War II. Steve's mother, Elfriede Anna Marie Sennholz (March 4, 1925 – July 16, 2013), worked as a seamstress. The two returned to Coos Bay after Ray met Elfriede in Germany while serving with the U.S. occupation forces.[8] The middle child and only son, he had two sisters, Neta and Linda,[4] and they all grew up in a house built by their father.[9]

Prefontaine was an exuberant person, even during his formative years. He was always moving around, partaking in different activities and events.[9] In junior high, Prefontaine was on his school's football and basketball teams but was rarely allowed to play because of his short stature.[9][10][11] In the eighth grade, he noticed several high school cross country team members jog to practice past the football field, an activity he then viewed as mundane. Later that year, he realized he could compete well in long-distance races during a three-week conditioning period in his physical education class.[9] By the second week of the daily mile runs, Prefontaine could finish second in the group. With this newfound success and athletic ability, he fell in love with cross country running.[11]

High school (1965–69)

When he got into Marshfield High School in the fall of 1965, Prefontaine joined the cross country team, coached by Walt McClure, Jr.[12] McClure had run under coach Bill Bowerman at the University of Oregon in Eugene and his father, Walt McClure, Sr. had run under Bill Hayward, also at Oregon.[10]

Prefontaine's freshman and sophomore years were decent, and he managed a personal best of 5:01 in the mile in his first year. Though starting as the seventh man, he progressed to be the second by the end of the year and placed 53rd in the state championship.[12] In his sophomore year; he failed to qualify for the state meet in his event, the two-mile. However, his coach recalls that it was his sophomore year when his potential in the sport began to surface.[12]

With the advice of Walt McClure, Prefontaine's high school coach, he took it upon himself to train hard over the summer.[12] He went through his junior cross country season undefeated and won the state title.[12][13]

In his senior year, many of his highest goals were set. He obtained a national record at the Corvallis Invitational with a time of 8:41.5, only one and a half seconds slower than his goal, and 6.9 seconds better than the previous record.[10][13] He won two more state titles that year after another undefeated season in both the one and two mile distances.[10][14]

Some forty colleges across the nation recruited Prefontaine,[11][15] and he received numerous phone calls, letters, and drop-in visits from coaches. He referred many of his calls to McClure, who wanted Prefontaine to attend the University of Oregon. McClure turned away those universities that began trying to recruit him late.[11][16] McClure maintained that he did not sway Prefontaine's collegiate choice, except to ask Steve where all the distance runners went to college.[10]

Prefontaine wanted to stay in-state for college[16] and attend the University of Oregon.[11] He had not heard much from Bill Bowerman, the head coach for the University of Oregon. Prefontaine only received letters from Oregon once a month, whereas other universities such as Villanova were persistent in recruiting him. As a result, Prefontaine did not know how much Bill Bowerman wanted him to attend Oregon.[11][16] Bowerman stated that he did not recruit Prefontaine differently from anyone else. It was a matter of principle for him to advise recruits where to attend college, wherever it may be, and to not bombard the recruits with correspondence.[11] He had followed Prefontaine's career since he was a sophomore and agreed with McClure in his assessment of Steve being a highly talented athlete.[16]

It wasn't until Prefontaine read Bowerman's letter that he decided to attend the University of Oregon. Bowerman wrote that he was 'certain' Prefontaine would become the world's greatest distance runner if he decided to run at Oregon. Although it was an odd promise, Prefontaine was up for the challenge.[11][16] Sometime after Prefontaine announced that he signed a letter of intent to attend Oregon on the first of May in 1969,[15][17] Bowerman wrote a letter addressed to the community of Coos Bay describing his appreciation for their role in helping Steve become a great runner.[16]

University of Oregon (1970–73)

Steve Prefontaine decided to enroll at the University of Oregon to train under coach Bill Bowerman (who in 1964 co-founded Blue Ribbon Sports, later to become known as Nike). He won four 5,000-meter titles in track three times in a row. At this time, he suffered only two more defeats in college (both in the mile), winning three Division I NCAA Cross Country Championships and four straight three-mile/5000-meter titles in track. He was a member of the Pi Kappa Alpha fraternity.

Prefontaine became known as a very aggressive front runner, insisting on going out hard from the start and not relinquishing leads, reminiscent of the renowned 1956 Olympic gold medalist Vladimir Kuts, another famous front runner at 5,000 meters. Prefontaine said, "No one will ever win a 5,000 meter race by running an easy first two miles. Not against me." He would later state, "I am going to work so that it's a pure guts race. In the end, if it is, I'm the only one that can win it". Along with his reputation for leading early instead of pacing himself until the last lap, Prefontaine had tremendous leg speed; his career-best for the mile (3:54.6) was only 3.5 seconds off the world record at the time.

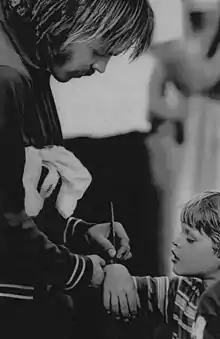

A local celebrity, chants of "Pre! Pre! Pre!" became a frequent feature at Hayward Field, a place where famous runners ran. Fans liked to wear T-shirts that read "LEGEND" or "GO PRE", though there was one instance where a group of fans jokingly put on shirts that read "STOP PRE". Prefontaine found humor in the shirts and, when offered, decided to wear one for his victory lap. Prefontaine rapidly gained national attention and appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated at age 19 in June 1970.[11] He was on the cover of Track and Field News's November 1969 issue.[18]

1972 Summer Olympics

In 1971, he began his training for the following year's Olympic Games in Munich, which had special meaning for his family (his mother was German, and his parents had met and married in Germany). Prefontaine set the American record of 13:22.8[19] in the 5,000 meters at the 1972 Olympic Trials in Eugene on July 9.[20] An underdog at the 1972 Olympics in Munich in September,[21] Prefontaine took the lead in the 5,000 m final during the last mile and ended the slow pace of the first two miles, negative splitting the race. In second place at the start of the bell lap, he fell back to third with 200 meters to go. Lasse Virén took the lead in the final turn over silver medalist Mohammed Gammoudi. Finding himself struggling to keep up, Prefontaine ran out of gas with only 10 meters to go as Britain's hard-charging Ian Stewart overtook him and moved into third place, depriving Prefontaine of an Olympic bronze medal.[22][23] Prefontaine later said "That was the most disappointed I have ever been. I guess I underestimated the strength of Viren and Gammoudi, and Stewart was way too good for me at the end. That last 200 metres, I felt exhausted. They didn't allow me to run the race the way I had planned to, I was chasing them all the way." Following his fourth-place finish in the Olympic Games, Prefontaine went back to the University of Oregon with a newfound enthusiasm for running after his disappointing showing at the Olympics.[24] This disappointment in his performance drove Pre to train harder than ever for his senior year of athletics, often logging over 10 miles per morning before he started his day.

In his four years at Oregon, Prefontaine never lost a collegiate (NCAA) race at 3 miles, 5,000 meters, 6 miles, or 10,000 meters. Returning for his senior year,[25] he ended his collegiate career with only three defeats in Eugene, all in the mile. It was during this year that Prefontaine began a protracted fight with the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU), which demanded that athletes who wanted to remain "amateur" for the Olympics not be paid for appearances in track meets. Some viewed this arrangement as unfair, because the participants drew large crowds that generated millions of dollars in revenue, with the athletes being forced to shoulder the burden of all their own expenses without assistance. At the time, the AAU was rescinding athletes' amateur status if they were endorsed in any way. Because Prefontaine was accepting free clothes and footwear from Nike, he was subject to the AAU's ruling.

After college (1974–75)

Following his collegiate career at Oregon, Prefontaine prepared for the 1976 Summer Olympics in Montreal. While running for the Oregon Track Club, Prefontaine set American records in every race from 2,000 to 10,000 meters.[13] In 1974, Prefontaine gave a presentation at a banquet. It was held in Eugene the night prior to the Junior College Cross Country Championships. Prefontaine talked about the importance of cross country through his own eyes. After his death, the notes Prefontaine made were given to his family.[26]

Death

In 1975, a group of traveling Finnish athletes took part in an NCAA Prep meet at Hayward Field in Eugene. After the event on Thursday, May 29, which included a 5,000-meter race that Prefontaine won, the Finnish and American athletes attended a party at the home of former Duck runner Geoff Hollister.[3][2] Shortly after midnight,[27] Prefontaine left the party to drive Frank Shorter to Kenny Moore's home on Prospect Drive, then descended narrow Skyline Boulevard alone, east of the university campus near Hendricks Park.[2][3] While in the extended right curve near the base, his gold-colored 1973 MGB convertible crossed the center line, jumped the curb, impacted a rock wall (44.0433°N 123.0549°W) and flipped, trapping him underneath it. One of the first persons on the scene was 20-year-old Karl Bylund, who raced from the scene in his car to his residence to get his dad, a doctor.[2][28] A nearby resident, Bill Alvarado (1936–2006), arrived next on the scene (he had heard Bylund's car screeching off) and reported he found Prefontaine flat on his back, still alive but pinned beneath the wreck. By the time medics arrived, he was pronounced dead. It had been reported that his blood alcohol content was found by the Eugene Police Department to be 0.16.[3][28][29] The official cause of death was traumatic asphyxiation and he had no other injuries that contributed.[30]

Prefontaine's body was buried in his hometown of Coos Bay at Sunset Memorial Park.[31] A day after his funeral in Coos Bay, a memorial service at Hayward Field in Eugene drew thousands.[32]

Aftermath

Eugene's Register-Guard called his death "the end of an era".[2] At his death, Prefontaine was probably the most popular athlete in Oregon and, along with Jim Ryun, Frank Shorter, Jeff Galloway and Bill Rodgers, was credited with sparking the national running boom of the 1970s.[33][34] An annual track event, the Prefontaine Classic, has been held in his memory since 1975. Known as the "Hayward Field Restoration Meet" in its first two years, it was rebranded as the "Bowerman Classic" for 1975 and set for June 7.[35] Two days after Prefontaine's death, it was renamed by the Oregon Track Club on June 1, with Bill Bowerman's approval, and the first "Pre Classic" was held six days later.[32][36]

During his career, Prefontaine won 120 of the 153 races he ran (.784), and never lost a collegiate (NCAA) track race longer than one mile at the University of Oregon. In 2020, SuperWest Sports included Prefontaine in its list of The Greatest Pac-12 Male Track and Field Athletes of All Time.[37]

Pre's Rock

Pre's Rock is a memorial at the base of the roadside outcrop where Prefontaine died.[38] An engraved stone memorial with a picture of Prefontaine, it reads:

"PRE"

For your dedication and loyalty

To your principles and beliefs...

For your love, warmth, and friendship

For your family and friends...

You are missed by so many

And you will never be forgotten...

Runners inspired by Prefontaine leave behind memorabilia to honor his memory and his continued influence, such as race numbers, medals, and running shoes. Paying such homage to Prefontaine has become a tradition that reaches a height during important or noteworthy running events in Eugene (e.g. the Olympic Trials or the Prefontaine Classic). As University of Oregon professor Daniel Wojcik documents in his study of the memorial, Pre's Rock has become both a grassroots shrine and pilgrimage site for athletes and non-athletes from around the world.[39][40]

Pre's Rock was dedicated in December 1997 and is maintained by Eugene Parks and Recreation as Prefontaine Memorial Park.[41] The rock (44.0433°N 123.0549°W) is a mile (1.6 km) due east of Hayward Field, just across the Willamette River from the east end of Pre's Trail. On Skyline Boulevard, it is approximately 150 feet (45 m) from its intersection with Birch Lane.[2]

Other memorials

The Prefontaine Memorial, featuring a relief of his face, records, and date of birth, is located at the Coos Bay Visitor Center in Coos Bay. In 2008, ten memorial plaques were laid along the Prefontaine Memorial Race route, the former training grounds of Prefontaine. The plaques bear an image of Prefontaine from his high school yearbook and various quotes and records from his time in Coos Bay. The plaques were part of a grant from the Oregon Tourism Commission, the Coos Bay-North Bend Visitor & Convention Bureau, and the Prefontaine Memorial Committee.

Each year on the third Saturday of September in Coos Bay, over a thousand runners engage in the Prefontaine Memorial Run, a 10k run honoring his accomplishments.[42]

The Coos Art Museum in Coos Bay contains a section dedicated to Prefontaine. This section includes medals he won during his career and the pair of spikes he wore when setting an American record for the 5,000 meters at Hayward Field.

Prefontaine was inducted into the Oregon Sports Hall of Fame in 1983, where several exhibits showcase his shoes, shirts, and other memorabilia. He was also inducted into the National Track and Field Hall of Fame in upper Manhattan[43] where one of his Oregon track uniforms is on display.

The Pete Susick Stadium at Marshfield High School in Coos Bay dedicated their track to honor Prefontaine, in April 2001.[44]

Nike used video footage in a commercial titled "Pre Lives" advertising his spirit for their product. On the 30th anniversary of his death in 2005, Nike placed a memorial advertisement in Sports Illustrated,[45] Eugene's Register-Guard,[46] and aired a television commercial in his honor. Nike's headquarters have a building named after him.[47]

The day after Prefontaine's death, the Register-Guard printed Ode to S. Roland, a poem by chief American rival Dick Buerkle.[48]

Prefontaine remains an iconic figure at the University of Oregon to this day. In 2020, the university polled alumni and fans on social media, asking them which four UO alumni they would place on a national Mount Rushmore for the university. Prefontaine was one of the four winners, along with Nike co-founder Phil Knight; current NFL player Marcus Mariota, the 2014 Heisman Trophy winner; and Sabrina Ionescu, who had just completed an epic college basketball career for the Ducks.[49]

In popular culture

Steve Prefontaine's life story has been detailed in two feature films: 1997's Prefontaine (starring Jared Leto as Prefontaine) and 1998's Without Limits (starring Billy Crudup as Prefontaine), as well as the documentary film Fire on the Track.

"Prefontaine" is the fifth track off Madchild's 2013 album "Lawn Mower Man".

Minnesota Golden Gopher Head Football Coach P.J. Fleck uses “Prefontaine Pace” among his many motivational sayings.[50]

"Prefontaine" is also the title of a song by hip hop duo Versatile.

Prefontaine is referenced in the chorus of the track "Strong" off Charles Wesley Godwin's 2021 album "How the Mighty Fall".

Personal bests

At the time of his death in May 1975, Prefontaine held every American outdoor track record between 2,000 and 10,000 meters. His personal best times over each distance, including those records, are below.[13]

| Surface | Event | Time | Date | Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outdoor track |

1,500 m | 3:38.1 | June 28, 1973 | Helsinki | 11th-place finish[51] |

| Mile | 3:54.6 | June 20, 1973 | Eugene | runner-up to Dave Wottle[52] | |

| 2,000 m | 5:01.4 | May 9, 1975 | Coos Bay | American record[53][54] | |

| 3,000 m | 7:42.6 | July 2, 1974 | Milan | American record, broken by Rudy Chapa, May 10, 1979[54][55] | |

| Two miles | 8:18.3 | July 18, 1974 | Stockholm | American record, broken by Marty Liquori, July 17, 1975[54][55][56] | |

| Three miles | 12:51.4 | June 8, 1974 | Eugene | American record[54] | |

| 5,000 m | 13:21.9 | June 26, 1974 | Helsinki | American record, broken by Duncan Macdonald, August 10, 1976[54][55] | |

| Six miles | 26:51.4 | April 27, 1974 | Eugene | American record, set in the first six miles of his 10,000 m record run (below)[54][57] | |

| 10,000 m | 27:43.6 | April 27, 1974 | Eugene | American record, broken by Craig Virgin, June 17, 1979[54][55] |

- Conversions: 1 mile (1,609.3 m), 2 miles (3,218.7 m), 3 miles (4,828 m), 6 miles (9,656 m)

Competition record

Notable performances

| Year | Competition | Venue | Position | Event | Time | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1968 | Corvallis Invitational | Corvallis, Oregon | 1st | 2 mile | 9:01.3 | Oregon high school record |

| 1969 | Corvallis Invitational | Corvallis, Oregon | 1st | 2 mile | 8:41.5 | US high school record |

| Coos County Meet | Coos Bay, Oregon | 1st | Mile | 4:06.9 | Oregon high school record | |

| US-USSR-Commonwealth Meet | Los Angeles, California | 5th | 5000 m | 14:40.0 | First international track meet | |

| 1970 | Oregon Twilight Meet | Eugene, Oregon | 2nd | Mile | 3:57.4 | First sub-4 min. mile |

| 1971 | Oregon vs. UCLA | Westwood, Los Angeles, California | 1st | Mile | 3:59.1 | |

| Oregon Twilight Meet | Eugene, Oregon | 2nd | Mile | 3:57.4 | ||

| US vs. USSR All Stars | Berkeley, California | 1st | 5000 m | 13:30.4 | American record | |

| Pan American Games | Cali, Colombia | 1st | 5000 m | 13:52.53 | ||

| 1972 | Oregon Indoor Invitational | Portland, Oregon | 1st | 2 mile | 8:26.6 | Collegiate record |

| All-Comers Spring Break Meet | Bakersfield, California | 1st | 6 mile | 27:22.4 | Collegiate record | |

| Oregon Twilight Meet | Eugene, Oregon | 1st | Mile | 3:56.7 | ||

| Oregon vs. Washington St. | Eugene, Oregon | 1st | 5000 m | 13:29.6 | American record | |

| Rose Festival | Gresham, Oregon | 1st | 3000 m | 7:45.8 | American record | |

| US Olympic Trials | Eugene, Oregon | 1st | 5000 m | 13:22.8[58] | American record | |

| Bislett Games | Oslo, Norway | 2nd | 1500 m | 3:39.4 | ||

| 1st | 3000 m | 7:44.2 | American record | |||

| Olympic Games | Munich, Germany | 4th | 5000 m | 13:28.4 | ||

| Zauli Memorial | Rome, Italy | 2nd | 5000 m | 13:26.4 | Three days after Olympics | |

| 1973 | Sunkist Invitational Indoor Meet | Los Angeles, California | 1st | 2 mile | 8:27.4 | |

| LA Times Invitational Indoor Games | Inglewood, California | 1st | Mile | 3:59.2 | ||

| Oregon Twilight II Meet | Eugene, Oregon | 1st | 2 mile | 8:24.6 | ||

| Hayward Field Restoration Meet | Eugene, Oregon | 2nd | Mile | 3:54.6 | personal best[52] | |

| World Games | Helsinki, Finland | 2nd | 5000 m | 13:22.4 | American record | |

| 1974 | Sunkist Invitational Indoor Meet | Los Angeles, California | 1st | 2 mile | 8:33.0 | |

| LA Times Invitational Indoor Games | Inglewood, California | 2nd | Mile | 3:59.5 | ||

| Oregon Twilight Meet | Eugene, Oregon | 1st | 10,000 m | 27:43.6 | American record; set American 6 mile record (26:51.4) en route | |

| Hayward Field Restoration Meet | Eugene, Oregon | 1st | 3 mile | 12:51.4 | American record | |

| World Games | Helsinki, Finland | 2nd | 5000 m | 13:21.9 | American record | |

| International Meet | Milan, Italy | 2nd | 3000 m | 7:42.6 | American record | |

| July Games | Stockholm, Sweden | 3rd | 2 mile | 8:18.4 | American record | |

| 1975 | CYO Invitational Indoor Meet | College Park, Maryland | 2nd | Mile | 3:58.6 | |

| Sunkist Invitational Indoor Meet | Los Angeles, California | 1st | 2 mile | 8:27.4 | ||

| Oregon Twilight Meet | Eugene, Oregon | 1st | 10,000 m | 28:09.4 | ||

| Finnish Tour | Coos Bay, Oregon | 1st | 2000 m | 5:01.4 | American record[53] | |

| California Relays | Modesto, California | 1st | 2 mile | 8:36.4 | ||

| NCAA Prep | Eugene, Oregon | 1st | 5000 m | 13:23.8 | Final race and 25th straight win in a distance over a mile |

US National Championships

| Year | Competition | Venue | Position | Event | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1969 | AAU Track and Field Championships | Miami, Florida | 4th | 3 mile | 13:43.0[a][59] |

| 1970 | AAU Track and Field Championships | Bakersfield, California | 5th | 3 mile | 13:26.0[59] |

| 1971 | AAU Track and Field Championships | Eugene, Oregon | 1st | 3 mile | 12:58.6[b][59] |

| 1973 | AAU Track and Field Championships | Bakersfield, California | 1st | 3 mile | 12:53.4[c][59] |

- a Third fastest 3-mile time ever run by an American high schooler; Prefontaine's first non-high school track meet

- b US National championships meet record; fifth fastest 3-mile time ever run and the second fastest by an American; Prefontaine's first sub-13 minute 3-mile[59]

- c Broke his own 1971 US National championships meet record; second fastest 3-mile time ever run by an American[59]

NCAA championships

While at Oregon Prefontaine won seven NCAA national titles: three in cross country, '70, '71 and '73; and four in track, '70, '71, '72 and '73. He was the first athlete to win four NCAA track titles in the same event.

Cross country

| Year | Competition | Venue | Position | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representing Oregon | ||||

| 1969 | NCAA Cross Country Championships | The Bronx, New York | 3rd | 29:12.0[60] |

| 1970 | NCAA Cross Country Championships | Williamsburg, Virginia | 1st | 28.00.2[61] |

| 1971 | NCAA Cross Country Championships | Knoxville, Tennessee | 1st | 29:14.0[62] |

| 1973 | NCAA Cross Country Championships | Spokane, Washington | 1st | 28:14.8[63] |

- Prefontaine redshirted the Fall of 1972 after the Olympics which made him eligible to run cross country in the fall of 1973.

Track and field

| Year | Competition | Venue | Position | Event | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representing Oregon | |||||

| 1970 | NCAA Outdoor Track and Field Championships | Drake Stadium (Des Moines, Iowa) |

1st | 3 mile | 13:22.0[a][64] |

| 1971 | NCAA Outdoor Track and Field Championships | Husky Stadium (Seattle, Washington) |

1st | 3 mile | 13:20.1[65] |

| 1972 | NCAA Outdoor Track and Field Championships | Hayward Field (Eugene, Oregon) |

1st | 5000 m[b] | 13:31.4[c][66] |

| 1973 | NCAA Outdoor Track and Field Championships | Bernie Moore Track Stadium (Baton Rouge, Louisiana) |

1st | 3 mile | 13:05.3[d][67] |

Oregon State high school championships

During his junior and senior years at Marshfield High School, Prefontaine went undefeated in both cross country and track.

Cross country

| Year | Competition | Venue | Position | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representing Marshfield High School | ||||

| 1965 | Oregon State Cross Country Championships | 53rd | NT[68] | |

| 1966 | Oregon State Cross Country Championships | 6th | 12:36[69] | |

| 1967 | Oregon State Cross Country Championships | 1st | 12:13.8[70] | |

| 1968 | Oregon State Cross Country Championships | 1st | 11:30.2[71] | |

References

- "Olympedia – Steve Prefontaine".

- Newnham, Blaine; Mack, Don (May 30, 1975). "Pre's death the end of an era". Eugene Register-Guard. p. 1A.

- Moore, Kenny (June 9, 1975). "A final drive to the finish". Sports Illustrated. p. 22.

- Anderson, Curtis (May 30, 2005). "Pre lives". Eugene Register-Guard. p. B1.

- Moore, Kenny (June 21, 2004). "Heaven sent". Sports Illustrated. p. 38.

- "Steve Prefontaine". National Distance Running Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on February 4, 2011. Retrieved February 19, 2007.

- "Tie-dyed Eugene unlikely home for football power". ESPN. January 8, 2011. Retrieved February 24, 2011.

- Jordan, Tom (1997). Pre: The Story of America's Greatest Running Legend, Steve Prefontaine (2nd ed.). Rodale Books. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-87596-457-7.

- Jordan (1997), pp. 5–6.

- Musca, Michael (April 2002). "In the Beginning". Running Times Magazine. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- Putnam, Pat (June 15, 1970). "The Freshman And The Great Guru". Sports Illustrated. 32 (24). Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- Jordan (1997), pp. 7–9.

- "Steve Prefontaine Bio & Pix". University of Oregon Athletics. Retrieved February 19, 2007.

- "Roseburg wins state Class A-1 championship". The Bulletin. Bend, Oregon. UPI. June 2, 1969. p. 10.

- "Prefontaine signs letter". The Bulletin. Bend, Oregon. UPI. May 2, 1969. p. 8.

- Jordan (1997), p. 11.

- Caraher, Pat (May 1, 1969). "Prefontaine will enroll at Oregon". Eugene Register-Guard. p. 1D.

- 1969 Covers (18-issue year). trackandfieldnews.com

- "Steve Prefontaine Bio & Pix". goducks.com. Retrieved November 8, 2018.

- Newnham, Blaine (July 10, 1972). "Pre wears down Young in 5,000 final". Eugene Register-Guard. p. 1B.

- Newnham, Blaine (September 10, 1972). "It's Pre versus the Europeans". Eugene Register-Guard. p. 1C.

- Newnham, Blaine (September 11, 1972). "Pre's warning for 1976: 'He'd better watch out'". Eugene Register-Guard. p. 1B.

- Newnham, Blaine (June 1, 1975). "Only first". Eugene Register-Guard. p. 1B.

- Jordan (1997), pp. 61–62.

- Reid, Ron (May 28, 1973). "Pre's last Duck-waddle". Sports Illustrated. p. 84.

- "Prefontaine Speech Notes From 1974". Prefontainerun.com. Retrieved November 15, 2013.

- "Prefontaine dies in auto accident". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Associated Press. May 30, 1975. p. 17.

- "Tests show Prefontaine was drunk". Milwaukee Journal. May 31, 1975. p. 11.

- Scott, Gerald (May 6, 1985). "The Legend Lives On: Even though Steve Prefontaine died almost 10 years ago, the memory of his life and controversy surrounding his death are as alive as ever". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- Frei, Dave (May 31, 1975). "He was Bill Bowerman's 'kind of guy'". Eugene Register-Guard. p. 1B.

- Newnham, Blaine (June 3, 1975). "Pre's last lap back where it began". Eugene Register-Guard. p. 1C.

- "Moore: I knew he was happy". Eugene-Register Guard. June 4, 1975. p. 1D.

- "Gorun.me". Archived from the original on February 12, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2012.

- "Steve Prefontaine (USA)". Runningthehighlands.com. Retrieved November 15, 2013.

- Newnham, Blaine (April 25, 1975). "A great season". Eugene-Register Guard. p. 1D.

- Newnham, Blaine (June 4, 1975). "The Pre Classic". Eugene-Register Guard. p. 1D.

- Ritchie, Steve (April 10, 2020). "Greatest Pac-12 Track & Field Athletes of All Time: Part I". SuperWest Sports. Retrieved October 11, 2022.

- Baker, Mark (May 30, 2005). "Land of the Pre". Sports Illustrated. p. 18.

- Wojcik, Daniel (2008). "Pre's Rock: Pilgrimage, Ritual, and Runners' Traditions at the Roadside Shrine for Steve Prefontaine." In Shrines and Pilgrimage in Contemporary Society: New Itineraries into the Sacred, ed. Peter Jan Margry, pp. 201–237. University of Amsterdam Press, 2008" (PDF). University of Oregon; Folklore and Public Culture Program.

- Wojcik, Daniel (2012). "Images of Pre's Rock". University of Oregon; Folklore and Public Culture Program.

- "Prefontaine Memorial Park". City of Eugene. Archived from the original on December 27, 2008. Retrieved March 18, 2008.

- Prefontaine Run Archived January 14, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- "Steve Prefontaine". USATF. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- The Steve Prefontaine Track Archived March 2, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- "Where are all the rock star runners?". Sports Illustrated (Advertisement). May 30, 2005. p. 52.

- "Where are all the rock star runners?". Eugene Register-Guard. (advertisement). May 30, 2005. p. B6.

- "Company Overview". Nikebiz Company Overview. Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- Buerkle, Dick (May 31, 1975). "Ode to S. Roland". Eugene Register-Guard. p. 1B.

- Foley, Damian (April 17, 2020). "The Gospel of Sab". Around the O. University of Oregon. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- Greder, Andy (January 27, 2017). "A peek into new Gophers coach P.J. Fleck's jargon". TwinCities.com. Retrieved June 15, 2021.

- "Wilkins wins at Toronto; Pre 11th at Helsinki". Eugene-Register Guard. June 29, 1973. p. 1D.

- Conrad, John (June 21, 1973). "Wottle (3:53.3) still king of the milers". Eugene-Register Guard. p. 1B.

- Conrad, John (May 10, 1975). "Pre's homecoming a big success". Eugene Register-Guard. p. 1D.

- "Steve Prefontaine Bio & Pix –". GoDucks.com. University of Oregon. Retrieved November 15, 2013.

- "USA Record Progressions- Track". arrs.run.

- "IAAF: Marty LIQUORI – Profile". iaaf.org. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- "Best times". Archived from the original on April 19, 2013.

- "Track and Field Statistics". trackfield.brinkster.net. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- US National Championships results Men's 5000 m Archived May 23, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Track and Field News. Retrieved on July 8, 2014

- 1969 Men's NCAA Cross Country Championships results. Track and Field News. Retrieved on July 8, 2014

- 1970 Men's NCAA Cross Country Championships results. Track and Field News. Retrieved on July 8, 2014

- 1971 Men's NCAA Cross Country Championships results. Track and Field News. Retrieved on July 8, 2014

- 1973 Men's NCAA Cross Country results. Track and Field News. Retrieved on July 8, 2014

- 1970 NCAA Men's Division I Outdoor Track and Field Championships results. Retrieved on July 8, 2014

- 1971 NCAA Men's Division I Outdoor Track and Field Championships results. Retrieved on July 8, 2014

- 1972 Men's Division I Outdoor Track and Field Championships results. Retrieved on July 8, 2014

- 1973 Men's NCAA Division I Outdoor Track and Field Championships results. Retrieved on July 8, 2014

- Oregon School Activities Association 1965 State Cross Country results. Retrieved on July 8, 2014

- Oregon School Activities Association 1966 State Cross Country results. Retrieved on July 8, 2014

- Oregon School Activities Association 1967 State Cross Country results. Retrieved on July 8, 2014

- Oregon School Activities Association 1968 State Cross Country results. Retrieved on July 8, 2014

- Oregon School Activities Association 1968 State Track and Field results. Retrieved on July 8, 2014

- Oregon School Activities Association 1969 State Track and Field results. Retrieved on July 8, 2014