Summa Theologica

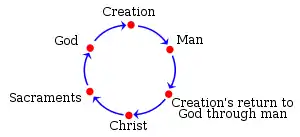

The Summa Theologiae or Summa Theologica (transl. 'Summary of Theology'), often referred to simply as the Summa, is the best-known work of Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), a scholastic theologian and Doctor of the Church. It is a compendium of all of the main theological teachings of the Catholic Church, intended to be an instructional guide for theology students, including seminarians and the literate laity. Presenting the reasoning for almost all points of Christian theology in the West, topics of the Summa follow the following cycle: God; Creation, Man; Man's purpose; Christ; the Sacraments; and back to God.

Page from an incunable edition of part II (Peter Schöffer, Mainz 1471) | |

| Author | Thomas Aquinas |

|---|---|

| Translator | Fathers of the English Dominican Province |

| Language | Latin |

| Subject | Christian theology |

| Publisher | Benziger Brothers Printers to the Holy Apostolic See |

Publication date | 1485 |

Published in English | 1911 |

| Media type | |

| 230.2 | |

| LC Class | BX1749 .T5 |

Original text | Summa Theologiae at Latin Wikisource |

| Translation | Summa Theologiae at Wikisource |

| Composed 1265–1274 | |

| Part of a series on |

| Thomas Aquinas |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Scholasticism |

|---|

|

|

Although unfinished, it is "one of the classics of the history of philosophy and one of the most influential works of Western literature."[1] Moreover, the Summa remains Aquinas' "most perfect work, the fruit of his mature years, in which the thought of his whole life is condensed."[2] Among non-scholars, the Summa is perhaps most famous for its five arguments for the existence of God, which are known as the "five ways" (Latin: quinque viae). The five ways, however, occupy only one of the Summa's 3,125 articles.

Throughout the Summa, Aquinas cites Christian, Muslim, Hebrew, and Pagan sources, including, but not limited to: Christian Sacred Scripture, Aristotle, Augustine of Hippo, Avicenna, Averroes, Al-Ghazali, Boethius, John of Damascus, Paul the Apostle, Pseudo-Dionysius, Maimonides, Anselm of Canterbury, Plato, Cicero, and John Scotus Eriugena.

The Summa is a more-structured and expanded version of Aquinas's earlier Summa contra Gentiles, though the two were written for different purposes. The Summa Theologiae intended to explain the Christian faith to beginning theology students, whereas the Summa contra Gentiles, to explain the Christian faith and defend it in hostile situations, with arguments adapted to the intended circumstances of its use, each article refuting a certain belief or a specific heresy.[3]

Aquinas conceived the Summa specifically as a work suited to beginning students:

Quia Catholicae veritatis doctor non solum provectos debet instruere, sed ad eum pertinet etiam incipientes erudire, secundum illud apostoli I ad Corinth. III, tanquam parvulis in Christo, lac vobis potum dedi, non escam; propositum nostrae intentionis in hoc opere est, ea quae ad Christianam religionem pertinent, eo modo tradere, secundum quod congruit ad eruditionem incipientium |

Because a doctor of catholic truth ought not only to teach the proficient, but to him pertains also to instruct beginners. As the Apostle says in 1 Corinthians 3: 1–2, as to infants in Christ, I gave you milk to drink, not meat, our proposed intention in this work is to convey those things that pertain to the Christian religion, in a way that is fitting to the instruction of beginners. |

| —"Prooemium," Summa theologiae I, 1. |

It was while teaching at the Santa Sabina studium provinciale—the forerunner of the Santa Maria sopra Minerva studium generale and College of Saint Thomas, which in the 20th century would become the Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas, Angelicum—that Aquinas began to compose the Summa. He completed the Prima Pars ('first part') in its entirety and circulated it in Italy before departing to take up his second regency as professor at the University of Paris (1269–1272).[4]

Not only has the Summa Theologiae been one of the main intellectual inspirations for Thomistic philosophy, but it also had such a great influence on Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy, that Dante's epic poem has been called "the Summa in verse".[5] Even today, both in Western and Eastern Catholic Churches, and the mainstream original Protestant denominations (Anglicanism and Episcopalianism, Lutheranism, Methodism, and Presbyterianism), it is very common for the Summa Theologiae to be a major reference for those seeking ordination to the diaconate or priesthood, or for professed male or female religious life, or for laypersons studying philosophy and theology at the collegiate level.

Structure

The Summa is structured into:

- 3 Parts ("Pt."), subdivided into:

- 614 Questions (quaestiones; or "QQ"), subdivided into:

- 3,125 Articles ("Art.").

- 614 Questions (quaestiones; or "QQ"), subdivided into:

Questions are specific topics of discussion, whereas their corresponding Articles are further-specified facets of the parent question. For example, Part I, Question 2 ("The Existence of God") is divided into three articles: (1) "Whether the existence of God is self-evident?"; (2) "Whether it can be demonstrated that God exists?"; and (3) "Whether God exists?" Additionally, questions on a broader theme are grouped into Treatises, though the category of treatise is reported differently, depending on the source.

The Summa's three parts have a few other major subdivisions.

- First Part (Prima Pars; includes 119 QQ, 584 Articles): The existence and nature of God; the creation of the world; angels; and the nature of man.

- Second Part (includes 303 QQ, 1536 Articles), subdivided into two sub-parts:

- First part of the Second Part (Prima Secundae or Part I-II; includes 114 QQ, 619 Articles): General principles of morality (including a theory of law).

- Second part of the Second Part (Secunda Secundae or Part II-II; includes 189 QQ, 917 Articles): Morality in particular, including individual virtues and vices.

- Third Part (Tertia Pars; includes 90 QQ, 549 Articles): The person and work of Christ, who is the way of man to God; and the sacraments. Aquinas left this part unfinished.[6]

- Supplement (99 QQ, 446 Articles): The third part proper is attended by a posthumous supplement which concludes the third part and the Summa, treating of Christian eschatology, or "the last things".

- Appendix I (includes 2 QQ, 8 Articles) and Appendix II (includes 1 Q, 2 Articles): Two very small appendices which discuss the subject of purgatory.

Article format

The method of exposition undertaken in the articles of the Summa is derived from Averroes, to whom Aquinas refers respectfully as "the Commentator".[7] The standard format for articles of the Summa are as follows:

- A series of objections (praeterea) to the yet-to-be-stated conclusion are given. This conclusion can mostly (but not without exception) be extracted by setting the introduction to the first objection into the negative.

- A short counter-statement is given, beginning with the phrase sed contra ('on the contrary...'). This statement almost always references authoritative literature, such as the Bible, Aristotle, or the Church Fathers.[8]

- The actual argument is made, beginning with the phrase respondeo dicendum quod conversatio ('I answer that...'). This is generally a clarification of the issue.

- Individual replies to the preceding objections or the counter-statement are given, if necessary. These replies range from one sentence to several paragraphs in length.

Example

Consider the example of Part III, Question 40 ("Of Christ's Manner of Life"),[lower-roman 1] Article 3 ("Whether Christ should have led a life of poverty in this world?"):[lower-roman 2]

- First, a series of objections to the conclusion are provided, followed by the extracted conclusion ('therefore'):

- Objection 1: "Christ should have embraced the most eligible form of life...which is a mean between riches and poverty.... Therefore Christ should have led a life, not of poverty, but of moderation."

- Objection 2: "Christ conformed His manner of life to those among whom He lived, in the matter of food and raiment. Therefore, it seems that He should have observed the ordinary manner of life as to riches and poverty, and have avoided extreme poverty."

- Objection 3: "Christ specially invited men to imitate His example of humility.... But humility is most commendable in the rich.... Therefore it seems that Christ should not have chosen a life of poverty."

- A counter-statement is given by referring to Matthew 8:20 and Matthew 17:26.

- The actual argument is made: "it was fitting for Christ to lead a life of poverty in this world" for four distinct reasons. The article then expounds on these reasons in detail.

- Aquinas' reply to the above objection is that "those who wish to live virtuously need to avoid abundance of riches and beggary...but voluntary poverty is not open to this danger: and such was the poverty chosen by Christ."

Structure of Part II

Part II of the Summa is divided into two parts (Prima Secundae and Secunda Secundae). The first part comprises 114 questions, while the second part comprises 189. The two parts of the second part are usually presented as containing several "treatises". The contents are as follows:[9]

Part II-I

- Treatise on the last end (qq. 1–5):[lower-roman 3]

- Treatise on human acts (qq. 6–21)[lower-roman 4]

- The will in general (qq. 6–7)

- The Will (qq. 8–17)

- Good and evil (qq. 8–21)

- Treatise on passions (qq. 22–48)[lower-roman 5]

- Passions in general (qq. 22–25)

- Love and hatred (qq. 26–29)

- Concupiscence and delight (qq. 30–34)

- Pain and sorrow (qq. 35–39)

- Fear and daring (qq. 40–45)

- Anger (qq. 46–48)

- Treatise on habits (qq. 49–70)[lower-roman 6]

- Habits in general; their causes and effects (qq. 49–54)

- Virtues; intellectual and moral virtues (qq. 55–60)

- Virtues; cardinal and theological virtues (qq. 61–67)

- The gifts, beatitudes and blessings of the Holy Ghost (qq. 68–70)

- Treatise on vice and sin (qq. 71–89)[lower-roman 7]

- Vice and sin in themselves; the comparison of sins (qq. 71–74)

- The general causes of sin; the internal causes of sin (qq. 75–78)

- The external causes of sin, such as the devil and man himself (qq. 79–84)

- The corruption of nature the stain of sin; punishment for venial and mortal sin (qq. 85–89)

- Treatise on law (qq. 90–108)[lower-roman 8]

- The essence of law; the various kinds of law; its effects (qq. 90–92)

- Eternal law, natural law, human law (qq. 93–97)

- The old law; ceremonial and judicial precepts (qq. 98–105)

- The law of the Gospel or new law (qq. 106–108)

- Treatise on grace (qq. 109–114): its necessity, essence, cause and effects[lower-roman 9]

Part II-II

- Treatise on the theological virtues (qq. 1–46)

- Treatise on the cardinal virtues (qq. 47–170)

- Treatise on prudence (qq. 47–56)

- Treatise on justice (qq. 57–122)

- Treatise on fortitude and temperance (qq. 123–170)

- Treatise on gratuitous graces (qq. 171–182)

- Treatise on the states of life (qq. 183–189)

References within the Summa

The Summa makes many references to certain thinkers held in great respect in Aquinas's time. The arguments from authority, or sed contra arguments, are almost entirely based on citations from these authors. Some were called by special names:

- The Apostle — Paul the Apostle: He wrote the majority of the New Testament canon after his conversion, earning him the title of The Apostle in Aquinas's Summa even though Paul was not among the original twelve followers of Jesus.

- The Philosopher — Aristotle: He was considered the most astute philosopher, the one who had expressed the most truth up to that time. The main aim of the Scholastic theologians was to use his precise technical terms and logical system to investigate theology.

- The Commentator — Averroes (Ibn Rushd): He was among the foremost commentators on Aristotle's works in Arabic, and his commentaries were often translated into Latin (along with Aristotle's text).

- The Master — Peter Lombard: Writer of the dominant theological text for the time: The Sentences (commentaries on the writings of the Doctors of the Church)

- The Theologian — Augustine of Hippo: Considered the greatest theologian who had ever lived up to that time; Augustine's works are frequently quoted by Aquinas.

- The Jurist or The Legal Expert (iurisperitus) — Ulpian (a Roman jurist): the most-quoted contributor to the Pandects.

- Tully — Marcus Tullius Cicero: famed Roman statesman and orator who was also responsible for bringing significant swathes of Greek philosophy to Latin-speaking audiences, though generally through summation and commentary in his own work rather than by translation.

- Dionysius — Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite: Aquinas refers to the works of Dionysius, whom scholars of the time thought to be the person mentioned in Acts 17:34 (a disciple of St. Paul). However, they were most likely written in Syria during the 6th century by a writer who attributed his book to Dionysius (hence the addition of the prefix "pseudo-" to the name "Dionysius" in most modern references to these works).

- Avicenna — Aquinas frequently cites this Persian polymath, the Aristotelian/Neoplatonic/Islamic philosopher Ibn Sina (Avicenna).

- Al-Ghazel —Aquinas also cites the Islamic theologian al-Ghazali (Algazel).

- Rabbi Moses — Rabbi Moses Maimonides: a Jewish rabbinical scholar, a near-contemporary of Aquinas (died 1204, before Aquinas). The scholastics derived many insights from his work, as he also employed the scholastic method.

- Damascene — John of Damascus: Syrian Christian monk and priest

Summary and key points

St. Thomas's greatest work was the Summa, and it is the fullest presentation of his views. He worked on it from the time of Clement IV (after 1265) until the end of his life. When he died, he had reached Question 90 of Part III (on the subject of penance).[9] What was lacking was added afterwards from the fourth book of his commentary on the Sentences of Peter Lombard as a supplementum, which is not found in manuscripts of the 13th and 14th centuries. The Summa was translated into: Greek (apparently by Maximus Planudes around 1327) and Armenian; many European languages; and Chinese.[9]

The structure of the Summa Theologiae is meant to reflect the cyclic nature of the cosmos, in the sense of the emission and return of the Many from and to the One in Platonism, cast in terms of Christian theology: The procession of the material universe from divine essence; the culmination of creation in man; and the motion of man back towards God by way of Christ and the Sacraments.[10]

The structure of the work reflects this cyclic arrangement. It begins with God and his existence in Question 2. The entire first part of the Summa deals with God and his creation, which reaches its zenith in man. The First Part, therefore, ends with the treatise on man. The second part of the Summa deals with man's purpose (the meaning of life), which is happiness. The ethics detailed in this part are a summary of the ethics (Aristotelian in nature) that man must follow to reach his intended destiny. Since no man on his own can truly live the perfect ethical life (and therefore reach God), it was necessary that a perfect man bridge the gap between God and man. Thus God became man. The third part of the Summa, therefore, deals with the life of Christ.

In order to follow the way prescribed by this perfect man, in order to live with God's grace (which is necessary for man's salvation), the Sacraments have been provided; the final part of the Summa considers the Sacraments.

Key points

- Theology is the most certain of all sciences because its source is divine knowledge (which cannot be deceived) and because of the greater worth of its subject matter, the sublimity of which transcends human reason.[lower-roman 10]

- When a man knows an effect and knows that it has a cause, the natural desire of the intellect or mind is to understand the essence of that thing. This understanding is necessary for the perfection of the intellect.[lower-roman 11]

- The existence of something and its essence are distinct (e.g., a mountain of solid gold would have essence, since it can be imagined, but not existence, since it is not in the world). More precisely, the being of something, and man's conception/imagination of such, are separate in all things—except for God, who is simple.[lower-roman 12]

- Human reasoning alone can prove: the existence of God; His total simplicity or lack of composition; his eternal nature (i.e., He exists outside of time, as time is held to be a part of God's created universe); His knowledge; the way His will operates; and His power. However, although St. Thomas felt that human reason alone could prove that God created the universe, reason alone could not determine whether the universe was eternal or actually began at some point in time. Rather, only divine revelation from the Book of Genesis proves that.[lower-roman 13][lower-roman 14]

- All statements about God are either analogical or metaphorical: one cannot say man is "good" in exactly the same sense as God, but rather that he imitates in some way the simple nature of God in being good, just, or wise.[lower-roman 15]

- 'Unbelief' is the worst sin in the realm of morals.[lower-roman 16]

- The principles of just war[lower-roman 17] and natural law[lower-roman 18]

- The greatest happiness of all, the ultimate good, consists in the beatific vision.[lower-roman 19]

- Collecting interest on loans is forbidden, because it is charging people twice for the same thing.[lower-roman 20]

- In and of itself, selling a thing for more or less than what it is worth is unlawful (the just price theory).[lower-roman 21]

- The contemplative life is greater than the active life.[lower-roman 22] What is even greater is the contemplative life that takes action to call others to the contemplative life and give them the fruits of contemplation.[lower-roman 23] (This actually was the lifestyle of the Dominican friars, of which St. Thomas was a member.)

- Both monks and bishops are in a state of perfection.[lower-roman 24] Being a monk is greater than being married and even greater (in many ways) than being a priest, but it is not as good as being a bishop.

- Although the Jews delivered Christ to die, it was the Gentiles who killed him, foreshadowing how salvation would begin with the Jews and spread to the Gentiles.[lower-roman 25]

- After the end of the world (in which all living material will be destroyed), the world will be composed of non-living matter (e.g. rocks), but it will be illuminated or enhanced in beauty by the fires of the apocalypse; a new heaven and earth will be established.[lower-roman 26]

- Martyrs, teachers of the faith (doctors), and virgins, in that order, receive special crowns in heaven for their achievements.[lower-roman 27]

- "The physicist proves the Earth to be round by one means, the astronomer by another: for the latter proves this by means of mathematics, e. g. by the shapes of eclipses, or something of the sort; while the former proves it by means of physics, e. g. by the movement of heavy bodies towards the center."[lower-roman 28]

Part I: Theology

The first part of the Summa is summed up in the premise that God governs the world as the "universal first cause". God sways the intellect; he gives the power to know and impresses the species intelligibiles on the mind, and he sways the will in that he holds the good before it as aim, creating the virtus volendi. "To will is nothing else than a certain inclination toward the object of the volition which is the universal good." God works all in all, but so that things also themselves exert their proper efficiency. Here the Areopagitic ideas of the graduated effects of created things play their part in St. Thomas's thought.[9]

Part I treats of God, who is the "first cause, himself uncaused" (primum movens immobile) and as such existent only in act (actu)—i.e. pure actuality without potentiality, and therefore without corporeality. His essence is actus purus et perfectus. This follows from the fivefold proof for the existence of God; namely, there must be a first mover, unmoved, a first cause in the chain of causes, an absolutely necessary being, an absolutely perfect being, and a rational designer. In this connection the thoughts of the unity, infinity, unchangeability, and goodness of the highest being are deduced.

As God rules in the world, the "plan of the order of things" preexists in him; in other words, his providence and the exercise of it in his government are what condition as cause everything which comes to pass in the world. Hence follows predestination: from eternity some are destined to eternal life, while as concerns others "he permits some to fall short of that end". Reprobation, however, is more than mere foreknowledge; it is the "will of permitting anyone to fall into sin and incur the penalty of condemnation for sin".

The effect of predestination is grace. Since God is the first cause of everything, he is the cause of even the free acts of men through predestination. Determinism is deeply grounded in the system of St. Thomas; things (with their source of becoming in God) are ordered from eternity as means for the realization of his end in himself.

On moral grounds, St. Thomas advocates freedom energetically; but, with his premises, he can have in mind only the psychological form of self-motivation. Nothing in the world is accidental or free, although it may appear so in reference to the proximate cause. From this point of view, miracles become necessary in themselves and are to be considered merely as inexplicable to man. From the point of view of the first cause, all is unchangeable, although from the limited point of view of the secondary cause, miracles may be spoken of.

In his doctrine of the Trinity, Aquinas starts from the Augustinian system. Since God has only the functions of thinking and willing, only two processiones can be asserted from the Father; but these establish definite relations of the persons of the Trinity, one to another. The relations must be conceived as real and not as merely ideal; for, as with creatures relations arise through certain accidents, since in God there is no accident but all is substance, it follows that "the relation really existing in God is the same as the essence according to the thing". From another side, however, the relations as real must be really distinguished one from another. Therefore, three persons are to be affirmed in God.

Man stands opposite to God; he consists of soul and body. The "intellectual soul" consists of intellect and will. Furthermore, the soul is the absolutely indivisible form of man; it is immaterial substance, but not one and the same in all men (as the Averroists assumed). The soul's power of knowing has two sides: a passive (the intellectus possibilis) and an active (the intellectus agens).

It is the capacity to form concepts and to abstract the mind's images (species) from the objects perceived by sense; but since what the intellect abstracts from individual things is universal, the mind knows the universal primarily and directly and knows the singular only indirectly by virtue of a certain reflexio (cf. Scholasticism). As certain principles are immanent in the mind for its speculative activity, so also a "special disposition of works"—or the synderesis (rudiment of conscience)—is inborn in the "practical reason", affording the idea of the moral law of nature so important in medieval ethics.

Part II: Ethics

The second part of the Summa follows this complex of ideas. Its theme is man's striving for the highest end, which is the blessedness of the visio beata. Here, St. Thomas develops his system of ethics, which has its root in Aristotle.

In a chain of acts of will, man strives for the highest end. They are free acts, insofar as man has in himself the knowledge of their end (and therein the principle of action). In that the will wills the end, it wills also the appropriate means, chooses freely and completes the consensus. Whether the act is good or evil depends on the end. The "human reason" pronounces judgment concerning the character of the end; it is, therefore, the law for action. Human acts, however, are meritorious insofar as they promote the purpose of God and his honor.

Sin

By repeating a good action, man acquires a moral habit or a quality that enables him to do the good gladly and easily. This is true, however, only of the intellectual and moral virtues (which St. Thomas treats after the manner of Aristotle); the theological virtues are imparted by God to man as a "disposition", from which the acts here proceed; while they strengthen, they do not form it. The "disposition" of evil is the opposite alternative.

An act becomes evil through deviation from the reason and from divine moral law. Therefore, sin involves two factors:

- its substance (or matter) is lust; and

- its form is deviation from the divine law.

Sin has its origin in the will, which decides (against reason) for a "changeable good". Since, however, the will also moves the other powers of man, sin has its seat in these too. By choosing such a lower good as its end, the will is misled by self-love, so that this works as cause in every sin. God is not the cause of sin since, on the contrary, he draws all things to himself; but from another side, God is the cause of all things, so he is efficacious also in sin as actio but not as ens. The devil is not directly the cause of sin, but he incites the imagination and the sensuous impulse of man (as men or things may also do).

Sin is original sin. Adam's first sin passes through himself to all the succeeding race; because he is the head of the human race and "by virtue of procreation human nature is transmitted and along with nature its infection." The powers of generation are, therefore, designated especially as "infected". The thought is involved here by the fact that St. Thomas, like other scholastics, believed in creationism; he therefore taught that souls are created by God.

Two things, according to St. Thomas, constituted man's righteousness in paradise:

- the justitia originalis ('original justice'), i.e., the harmony of all man's powers before they were blighted by desire; and

- the possession of the gratis gratum faciens (the continuous, indwelling power of good).

Both are lost through original sin, which, in form, is the "loss of original righteousness". The consequence of this loss is the disorder and maiming of man's nature, which shows itself in "ignorance; malice, moral weakness, and especially in concupiscentia, which is the material principle of original sin." The course of thought here is as follows: when the first man transgressed the order of his nature appointed by nature and grace, he (and with him the human race) lost this order. This negative state is the essence of original sin. From it follow an impairment and perversion of human nature in which thenceforth lower aims rule, contrary to nature, and release the lower element in man.

Since sin is contrary to the divine order, it is guilt and subject to punishment. Guilt and punishment correspond to each other; and since the "apostasy from the invariable good which is infinite," fulfilled by man, is unending, it merits everlasting punishment.

God works even in sinners to draw them to the end by "instructing through the law and aiding by grace." The law is the "precept of the practical reason". As the moral law of nature, it is the participation of the reason in the all-determining "eternal reason"; but since man falls short in his appropriation of this law of reason, there is need of a "divine law"; and since the law applies to many complicated relations, the practicae dispositiones of the human law must be laid down.

Grace

The divine law consists of an old and a new. Insofar as the old divine law contains the moral law of nature, it is universally valid; what there is in it, however, beyond this is valid only for the Jews. The new law is "primarily grace itself" and so a "law given within"; "a gift superadded to nature by grace", but not a "written law". In this sense, as sacramental grace, the new law justifies. It contains, however, an "ordering" of external and internal conduct and so regarded is, as a matter of course, identical with both the old law and the law of nature. The consilia show how one may attain the end "better and more expediently" by full renunciation of worldly goods.

Since man is sinner and creature, he needs grace to reach the final end. The "first cause" alone is able to reclaim him to the "final end". This is true after the fall, although it was needful before. Grace is, on one side, "the free act of God", and, on the other side, the effect of this act, the gratia infusa or gratia creata, a habitus infusus that is instilled into the "essence of the soul... a certain gift of disposition, something supernatural proceeding from God into man." Grace is a supernatural ethical character created in man by God, which comprises in itself all good, both faith and love.

Justification by grace comprises four elements:[9]

- "infusion of grace";

- "the influencing of free will toward God through faith";

- the influencing of free will respecting sin"; and

- "the remission of sins".

Grace is a "transmutation of the human soul" that takes place "instantaneously". A creative act of God enters, which executes itself as a spiritual motive in a psychological form corresponding to the nature of man. Semi-pelagian tendencies are far removed from St. Thomas. In that man is created anew, he believes and loves, and now, sin is forgiven. Then begins good conduct; grace is the "beginning of meritorious works". Aquinas conceives of merit in the Augustinian sense: God gives the reward for that toward which he himself gives the power. Man can never of himself deserve the prima gratis, nor meritum de congruo (by natural ability; cf. R. Seeberg, Lehrbuch der Dogmengeschichte, ii. 105–106, Leipsic, 1898).

Virtues

After thus stating the principles of morality, in the Secunda Secundae, St. Thomas comes to a minute exposition of his ethics according to the scheme of the virtues. The conceptions of faith and love are of much significance in the complete system of St. Thomas. Man strives toward the highest good with the will or through love; but since the end must first be "apprehended in the intellect", knowledge of the end to be loved must precede love; "because the will can not strive after God in perfect love unless the intellect have true faith toward him."

Inasmuch as this truth that is to be known is practical, it first incites the will, which then brings the reason to "assent"; but since, furthermore, the good in question is transcendent and inaccessible to man by himself, it requires the infusion of a supernatural "capacity" or "disposition" to make man capable of faith as well as love.

Accordingly, the object of both faith and love is God, involving also the entire complex of truths and commandments that God reveals, insofar as they in fact relate to God and lead to him. Thus, faith becomes recognition of the teachings and precepts of the Scriptures and the Church ("the first subjection of man to God is by faith"). The object of faith, however, is, by its nature, object of love; therefore, faith comes to completion only in love ("by love is the act of faith accomplished and formed").

Law

Law is nothing else than an ordinance of reason for the common good, made by him who has care of the community, and promulgated.

— Summa Theologica, Pt. II-II, Q. 90, Article 4

All law comes from the eternal law of Divine Reason that governs the universe, which is understood and participated in by rational beings (such as men and angels) as the natural law. The natural law, when codified and promulgated, is lex humana ('human law').[lower-roman 8]

In addition to the human law, dictated by reason, man also has the divine law, which, according to Question 91, is dictated through revelation, that man may be "directed how to perform his proper acts in view of his last end", "that man may know without any doubt what he ought to do and what he ought to avoid", because "human law could not sufficiently curb and direct interior acts", and since "human law cannot punish or forbid all evil deeds: since while aiming at doing away with all evils, it would do away with many good things, and would hinder the advance of the common good, which is necessary for human intercourse." Human law is not all-powerful; it cannot govern a man's conscience, nor prohibit all vices, nor can it force all men to act according to its letter, rather than its spirit.

Furthermore, it is possible that an edict can be issued without any basis in law as defined in Question 90; in this case, men are under no compulsion to act, save as it helps the common good. This separation between law and acts of force also allows men to depose tyrants, or those who flout the natural law; while removing an agent of the law is contrary to the common good and the eternal law of God, which orders the powers that be, removing a tyrant is lawful as he has ceded his claim to being a lawful authority by acting contrary to law.

Part III: Christ

The way which leads to God is Christ, the theme of Part III. It can be asserted that the incarnation was absolutely necessary. The Unio between the Logos and the human nature is a "relation" between the divine and the human nature, which comes about by both natures being brought together in the one person of the Logos. An incarnation can be spoken of only in the sense that the human nature began to be in the eternal hypostasis of the divine nature. So Christ is unum since his human nature lacks the hypostasis.

The person of the Logos, accordingly, has assumed the impersonal human nature, and in such way that the assumption of the soul became the means for the assumption of the body. This union with the human soul is the gratia unionis, which leads to the impartation of the gratia habitualis from the Logos to the human nature. Thereby, all human potentialities are made perfect in Jesus. Besides the perfections given by the vision of God, which Jesus enjoyed from the beginning, he receives all others by the gratia habitualis. Insofar, however, as it is the limited human nature which receives these perfections, they are finite. This holds both of the knowledge and the will of Christ.

The Logos impresses the species intelligibiles of all created things on the soul, but the intellectus agens transforms them gradually into the impressions of sense. On another side, the soul of Christ works miracles only as instrument of the Logos, since omnipotence in no way appertains to this human soul in itself. Concerning redemption, St. Thomas teaches that Christ is to be regarded as redeemer after his human nature but in such way that the human nature produces divine effects as organ of divinity.

The one side of the work of redemption consists herein, that Christ as head of humanity imparts ordo, perfectio, and virtus to his members. He is the teacher and example of humanity; his whole life and suffering as well as his work after he is exalted serve this end. The love wrought hereby in men effects, according to Luke vii. 47, the forgiveness of sins.

This is the first course of thought. Then follows a second complex of thoughts, which has the idea of satisfaction as its center. To be sure, God as the highest being could forgive sins without satisfaction; but because his justice and mercy could be best revealed through satisfaction, he chose this way. As little, however, as satisfaction is necessary in itself, so little does it offer an equivalent, in a correct sense, for guilt; it is rather a "superabundant satisfaction", since on account of the divine subject in Christ in a certain sense his suffering and activity are infinite.

With this thought, the strict logical deduction of Anselm's theory is given up. Christ's suffering bore personal character in that it proceeded "out of love and obedience". It was an offering brought to God, which as a personal act had the character of merit. Thereby, Christ "merited" salvation for men. As Christ, exalted, still influences men, so does he still work on their behalf continually in heaven through the intercession (interpellatio).

In this way, Christ as head of humanity effects the forgiveness of their sins, their reconciliation with God, their immunity from punishment, deliverance from the devil, and the opening of heaven's gate; but inasmuch as all these benefits are already offered through the inner operation of the love of Christ, Aquinas has combined the theories of Anselm and Abelard by joining the one to the other.

The sacraments

The doctrine of the sacraments follows the Christology; the sacraments "have efficacy from the incarnate Word himself". They are not only signs of sanctification, but also bring it about. It is inevitable that they bring spiritual gifts in sensuous form, because of the sensuous nature of man. The res sensibiles are the matter, the words of institution the form of the sacraments. Contrary to the Franciscan view that the sacraments are mere symbols whose efficacy God accompanies with a directly following creative act in the soul, St. Thomas holds it not unfit to agree with Hugo of St. Victor that "a sacrament contains grace", or to teach that they "cause grace".

St. Thomas attempts to remove the difficulty of a sensuous thing producing a creative effect, by distinguishing between the causa principalis et instrumentalis. God, as the principal cause, works through the sensuous thing as the means ordained by him for his end. "Just as instrumental power is acquired by the instrument from this, that it is moved by the principal agent, so also the sacrament obtains spiritual power from the benediction of Christ and the application of the minister to the use of the sacrament. There is spiritual power in the sacraments in so far as they have been ordained by God for a spiritual effect." This spiritual power remains in the sensuous thing until it has attained its purpose. At the same time, St. Thomas distinguished the gratia sacramentalis from the gratia virtutum et donorum, in that the former perfects the general essence and the powers of the soul, whilst the latter in particular brings to pass necessary spiritual effects for the Christian life. Later, this distinction was ignored.

In a single statement, the effect of the sacraments is to infuse justifying grace into men. That which Christ effects is achieved through the sacraments. Christ's humanity was the instrument for the operation of his divinity; the sacraments are the instruments through which this operation of Christ's humanity passes over to men. Christ's humanity served his divinity as instrumentum conjunctum, like the hand; the sacraments are instrumenta separata, like a staff; the former can use the latter, as the hand can use a staff. (For a more detailed exposition, cf. Seeberg, ut sup., ii. 112 sqq.)

Eschatology

Of St. Thomas's eschatology, according to the commentary on the Sentences, this is only a brief account. Everlasting blessedness consists in the vision of God – this vision consists not in an abstraction or in a mental image supernaturally produced, but the divine substance itself is beheld, and in such manner that God himself becomes immediately the form of the beholding intellect. God is the object of the vision and, at the same time, causes the vision.

The perfection of the blessed also demands that the body be restored to the soul as something to be made perfect by it. Since blessedness consists in operatio, it is made more perfect in that the soul has a definite operatio with the body, although the peculiar act of blessedness (in other words, the vision of God) has nothing to do with the body.

Editions and translations

Editions

Early partial editions were printed still in the 15th century, as early as 1463; an edition of the first section of part 2 was printed by Peter Schöffer of Mainz in 1471.[11] A full edition was printed by Michael Wenssler of Basel in 1485.[12] From the 16th century, numerous commentaries on the Summa were published, notably by Peter Crockaert (d. 1514), Francisco de Vitoria and by Thomas Cajetan (1570).

- 1663. Summa totius theologiae (Ordinis Praedicatorum ed.), edited by Gregorio Donati (d. 1642)

- 1852–73. Parma edition. Opera Omnia, Parma: Fiaccadori.

- 1871–82. Vivès edition. Opera Omnia, Paris: Vivès.

- 1886. Editio altera romana, edited by Pope Leo XIII. Forzani, Rome.[13]

- 1888. Leonine Edition, edited by Roberto Busa, with commentary by Thomas Cajetan.[14]

- 1964–80. Blackfriars edition (61 vols., Latin and English with notes and introductions, London: Eyre & Spottiswoode (New York: McGraw-Hill. 2006. ISBN 9780521690485 pbk).

Translations

The most accessible English translation of the work is that originally published by Benziger Brothers, in five volumes, in 1911 (with a revised edition published in 1920).

The translation is entirely the work of Laurence Shapcote (1864-1947), an English Dominican friar. Wanting to remain anonymous, however, he attributed the translation to the Fathers of the English Dominican Province. Father Shapcote also translated various of Aquinas's other works.[15]

- 1886–1892. Die katholische Wahrheit oder die theologische Summa des Thomas von Aquin (in German), translated by C.M Schneider. Regensburg: G. J. Manz.[16]

- 1911. The Summa Theologiæ of St. Thomas Aquinas, translated by Fathers of the English Dominican Province. New York: Benzinger Brothers.

- 1927–43. Theologische Summa (in Dutch), translated by Dominicanen Order. Antwerpen.[19]

- 1964–80. Blackfriars edition (61 vols., Latin and English with notes and introductions, London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, and New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company), paperback edition 2006 (ISBN 9780521690485).

- 1989. Summa Theologiae: A Concise Translation, T. McDermott. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode.

See also

- List of works by Thomas Aquinas

- Sentences of Peter Lombard

- Summa logicae of William of Ockham

- Antoninus of Florence (d. 1459), author of a Summa theologica printed in 1477

References

Primary sources

- Summa Theologica, Pt. III, Q. 40. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Summa Theologica, Pt. III, Q. 40, Art. 3. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Summa Theologica, Pt. II-I, Q. 1–5.

- Summa Theologica, Pt. II-I, Q. 1–21.

- Summa Theologica, Pt. II-I, Q. 22–48.

- Summa Theologica, Pt. II-I, Q. 49–70.

- Summa Theologica, Pt. II-I, Q. 71–89.

- Summa Theologica, Pt. II-I, Q. 90–108.

- Summa Theologica, Pt. II-I, Q. 109–114.

- Summa Theologica, Pt. I, Q. 1, Art. 5. Retrieved 11 July 2006.

- Summa Theologica, Pt. II-I, Q. 3, Art. 8; and Art. 6-7.

- Summa Theologica, Pt. I, Q. 3, Art. 4. Aquinas develops this line of thought more fully in a shorter work, De ente et essentia.

- Romans 1:19–20

- Summa Theologica, Pt. I, Q. 2, Art. 2. See also: Pt. I, Q. 1, Art. 8.

- Summa Theologica, Pt. I, Q. 4, Art. 3.

- Summa Theologica, Pt. II-II, Q. 10, Art. 3. Retrieved 11 July 2006. However, at other points, Aquinas, with different meanings of "great" makes the claim for pride, despair, and hatred of God.

- Summa Theologica, Pt. II-II, Q. 40.

- Summa Theologica, Pt. I-II, Q. 91, Art. 2; and Pt. I-II, Q. 94.

- Summa Theologica, Pt. I-II, Q. 2, Art. 8.

- Summa Theologica, Pt. II-II, Q. 78, Art. 1.

- Summa Theologica, Pt. II-II, Q. 77, Art. 1.

- Summa Theologica, Pt. II-II, Q. 182, Art. 1.

- Summa Theologica, Pt. II-II, Q. 182, Art. 4.

- Summa Theologica, Pt. II-II, Q. 184.

- Summa Theologica, Pt. III, Q. 47, Art. 4.

- Supplement, Q. 91; and Supplement, Q. 74, Art. 9.

- Supplement, Q. 96, Arts. 5–7.

- Summa Theologica, Pt. I-II, Q. 54, Art. 2.

Citations

- Ross, James F. 2003. "Thomas Aquinas, 'Summa theologiae' (ca. 1273), Christian Wisdom Explained Philosophically." P. 165 in The Classics of Western Philosophy: A Reader's Guide, edited by J. J. E. Gracia, G. M. Reichberg, B. N. Schumacher. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9780631236115.

- Perrier, Joseph Louis. 1909. "The Revival of Scholastic Philosophy in the Nineteenth Century." New York: Columbia University Press. pg. 149.

- Gilson, Etienne (1994). The Christian Philosophy of Saint Thomas Aquinas. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press. p. 502. ISBN 978-0-268-00801-7.

- Torrell, Jean-Pierre. 1996. Saint Thomas Aquinas, vol 1, The Person and His Work, translated by Robert Royal. Catholic University. 146 ff.

- Fordham University. Oct. 1921–June 1922. The Fordham Monthly 40:76.

- McInerny, Ralph. 1990. A First Glance at St. Thomas Aquinas. Notre Dame Press: Indiana. ISBN 0-268-00975-9. p.197.

- "St. Thomas Aquinas used the "Grand Commentary" of Averroes as his model, being, apparently, the first Scholastic to adopt that style of exposition..." Turner, William. 1907. "Averroes." In The Catholic Encyclopedia 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 2009-11-06.

- Kreeft, Peter. 1990. Summa of the Summa. Ignatius Press. pp. 17–18. ISBN 0-89870-300-X.

- 1911. "Thomas Aquinas." In The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge 11. pp. 422–27.

- O'Meara, Thomas Franklin. 2006. Summa Theologiae: Volume 40, Superstition and Irreverence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. xix.

- Bridwell Library (smu.edu)

- OCLC 699664146.

- Pope Leo XIII, ed. 1886. Summa Theologica (editio altera romana). Rome: Forzani.

- Busa, Roberto, ed. 1888. Summa Theologiae (Leonine ed.), with commentary by T. Cajetan. – via Corpus Thomisticum.

- "Thomas Aquinas's 'Summa Theologiae': A Guide and Commentary" by Brian Davies [Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014, p. xiv]. From 1917 until his death, Shapcote was based in Natal Province, South Africa. Fergus Kerr, "The Shapcote Translation", New Blackfriars (August 2011), doi:10.1111/j.1741-2005.2011.01454.x.

- Emmenegger, Gregor, ed. 2008. "Summe der Theologie" (in German), transcribed by F. Fabri. Bibliothek der Kirchenväter. Fribourg: Université Fribourg.

- Aquinas, Thomas. 1920. The Summa Theologiæ of St. Thomas Aquinas (revised ed.), translated by Fathers of the English Dominican Province. – via New Advent.— Summa Theologica, (Complete American edition) at Project Gutenberg

- 1947. Summa Theologica (reissue, 3 vols.). New York: Benzinger Brothers. ASIN 0870610635. – via Sacred Texts. IntraText edition (2007).

- Beenakker, Carlo, ed. Theologische Summa, translated by Dominicanen Order. Antwerpen.

References

- Perrier, Joseph Louis. 1909. The Revival of Scholastic Philosophy in the Nineteenth Century. New York: The Columbia University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Seeburg, Reinhold (1914). "Thomas Aquinas". In Jackson, Samuel Macauley (ed.). New Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge. Vol. XI (third ed.). London and New York: Funk and Wagnalls. pp. 422–427.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Seeburg, Reinhold (1914). "Thomas Aquinas". In Jackson, Samuel Macauley (ed.). New Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge. Vol. XI (third ed.). London and New York: Funk and Wagnalls. pp. 422–427.

Further reading

- McGinn, Bernard (2014). Thomas Aquinas's Summa theologiae: A Biography. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15426-8.

- Thomas Aquinas (1952), edd. Walter Farrell, OP, and Martin J. Healy, My Way of Life: Pocket Edition of St. Thomas—The Summa Simplified for Everyone, Brooklyn: Confraternity of the Precious Blood.

- Pegues (O.P.), Thomas; Whitacre (O.P.), Ælred (1922). Catechism of the Summa theologica of Saint Thomas Aquinas for the use of the faithful. archive.org. London: Burns, Oates & Washbourne. p. 344. Archived from the original on November 18, 2018. (with imprimatur of Edmund Canon Surmont, General of Westminster)

External links

- Online edition

- Latin-English version

- Intratext version

- Summa Theologiæ (A Searchable Latin text for Android devices)

Summa Theologica public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Summa Theologica public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Summa Theologiae (A new English translation in progress, by Alfred Freddoso)

- Prima pars secunde partis Summe Theologie beati Thome de Aquino. Naples, 1484. (Digitized codex, Latin text, at Somni)