Trajan's Bridge

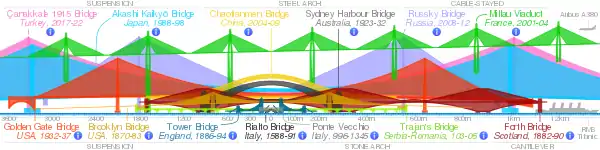

Trajan's Bridge (Romanian: Podul lui Traian; Serbian: Трајанов мост / Trajanov most), also called Bridge of Apollodorus over the Danube, was a Roman segmental arch bridge, the first bridge to be built over the lower Danube and one of the greatest achievements in Roman architecture. Though it was only functional for 165 years, it is often considered to be the longest arch bridge in both total and span length for more than 1,000 years.[1]

Trajan's Bridge | |

|---|---|

Artistic reconstruction (1907) | |

| Coordinates | 44.623769°N 22.66705°E |

| Crosses | Danube |

| Locale | East of the Iron Gates, in Drobeta-Turnu Severin (Romania) and near the city of Kladovo (Serbia) |

| Heritage status | Monuments of Culture of Exceptional Importance, and Archaeological Sites of Exceptional Importance (Serbia) |

| Characteristics | |

| Material | Wood and Stone |

| Total length | 1,135 m (3,724 ft) |

| Width | 15 m (49 ft) |

| Height | 19 m (62 ft) |

| No. of spans | 20 masonry pillars |

| History | |

| Architect | Apollodorus of Damascus |

| Construction start | 103 A.D. |

| Construction end | 105 A.D. |

| Collapsed | Superstructure destroyed by Aurelian around 270 A.D. |

| Location | |

| |

The bridge was constructed in 105 AD by instruction of Emperor Trajan by architect Apollodorus of Damascus, from Damascus, Roman Syria, before his Second Dacian War to allow Roman troops to cross the river. Fragmentary ruins of the bridge's piers can still be seen today.

Description

.jpg.webp)

The bridge was situated east of the Iron Gates, near the present-day cities of Drobeta-Turnu Severin in Romania and Kladovo in Serbia. Its construction was ordered by the Emperor Trajan as a supply route for the Roman legions fighting in Dacia.

The structure was 1,135 m (3,724 ft) long (the Danube is now 800 m (2,600 ft) wide in that area), 15 m (49 ft) wide, and 19 m (62 ft) high, measured from the surface of the river. At each end was a Roman castrum, each built around an entrance, so that crossing the bridge was possible only by walking through the camps.

The castra were called Pontes and Drobeta (Drobetis). On the right bank, at the modern village of Kostol near Kladovo, a castrum Pontes with a civilian settlement was built in 103. It occupied several hectares and was built concurrently with the bridge. Remnants of the 40 m (130 ft) long castrum with thick ramparts are still visible today. Fragments of ceramics, bricks with Roman markings, and coins have been excavated. A bronze head of Emperor Trajan has also been discovered in Pontes. It was part of a statue which was erected at the bridge entrance and is today kept in the National Museum in Belgrade. On the left bank there was a Drobeta castrum. There was also a bronze statue of Trajan on that side of the bridge.[2]

The bridge's engineer, Apollodorus of Damascus, used wooden arches, each spanning 38 m (125 ft), set on twenty masonry pillars made of bricks, mortar, and pozzolana cement.[3][4] It was built unusually quickly (between 103 and 105), employing the construction of a wooden caisson for each pier.[5]

Apollodorus applied the technique of river flow relocation, using the principles set by Thales of Miletus some six centuries beforehand. Engineers waited for a low water level to dig a canal, west of the modern downtown of Kladovo. The water was redirected 2 km (1.2 mi) downstream from the construction site, through the lowland of Ključ region, to the location of the modern village of Mala Vrbica. Wooden pillars were driven into the river bed in a rectangular layout, which served as the foundation for the supporting piers, which were coated with clay. The hollow piers were filled with stones held together by mortar, while from the outside they were built around with Roman bricks. The bricks can still be found around the village of Kostol, retaining the same physical properties that they had 2 millennia ago. The piers were 44.46 m (145.9 ft) tall, 17.78 m (58.3 ft) wide and 50.38 m (165.3 ft) apart.[6] It is considered today that the bridge construction was assembled on the land and then installed on the pillars. A mitigating circumstance was that the year the relocating canals were dug was very dry and the water level was quite low. The river bed was almost completely drained when the foundation of the pillars began. There were 20 pillars in total in an interval of 50 m (160 ft). Oak wood was used and the bridge was high enough to allow ship transport on the Danube.[2]

.jpg.webp)

The bricks also have a historical value, as the members of the Roman legions and cohorts which participated in the construction of the bridge carved the names of their units into the bricks. Thus, it is known that work was done by the legions of IV Flavia Felix, VII Claudia, V Macedonica and XIII Gemina and the cohorts of I Cretum, II Hispanorum, III Brittonum and I Antiochensium.[6]

Construction of the bridge was part of a wider project, which included the digging of sideway canals so that whitewater rapids could be avoided in order to make the Danube safer for navigation, building of a powerful river fleet and defense posts, and development of the intelligence service on the border.

The Iron Gate Cataract was especially problematic, as navigation was not possible during low waters, when the rocky and lumpy river bed would block the passage of ships on the entire width of the Danube. As the heavy equipment necessary for lifting major boulders from the river bed and dragging them onto the bank wasn't available at the time, the Roman engineers decided to cut the canal through the stone slopes on the west bank. It began from the Iron Gate, going upstream to the point where the rapids start, which is a bit downstream from the modern village of Novi Sip.

The remains of the embankment which protected the area during the construction of the canal show the magnitude of the works. The 3.2 km (2.0 mi) long canal bypassed the problematic section of the river in an arch-like style.[6] Former canals were filled with sand, and empty shells are regularly found in the ground.[2]

All these works, especially the bridge, served the purpose of preparing for the Roman invasion of Dacia, which ended with Roman victory in 106 AD. The effect of finally defeating the Dacians and acquiring their gold mines was so great that Roman games celebrating the conquest lasted for 123 days, with 10,000 gladiators engaging in fights and 11,000 wild animals being killed during that period.[6]

Tabula Traiana

A Roman memorial plaque ("Tabula Traiana"), 4 metres wide and 1.75 metres high, commemorating the completion of Trajan's military road is located on the Serbian side facing Romania near Ogradina. In 1972, when the Iron Gate I Hydroelectric Power Station was built (causing the water level to rise by about 35m), the plaque was moved from its original location, and lifted to the present place. It reads:

- IMP. CAESAR. DIVI. NERVAE. F

NERVA TRAIANVS. AVG. GERM

PONTIF MAXIMUS TRIB POT IIII

PATER PATRIAE COS III

MONTIBVS EXCISI(s) ANCO(ni)BVS

SVBLAT(i)S VIA(m) F(ecit)

The text was interpreted by Otto Benndorf to mean:

- Emperor Caesar son of the divine Nerva, Nerva Trajan, the Augustus, Germanicus, Pontifex Maximus, invested for the fourth time as Tribune, Father of the Fatherland, Consul for the third time, excavating mountain rocks and using wood beams has made this road.

The Tabula Traiana was declared a Monument of Culture of Exceptional Importance in 1979, and is protected by the Republic of Serbia.

Relocation

.jpg.webp)

When the plan for the future hydro plant and its reservoir was made in 1965, it was clear that numerous settlements along the banks would be flooded in both Yugoslavia and Romania, and that historical remains, including the plaque, would also be affected. Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts urged for the plaque to be preserved and the government accepted the motion. The enterprise entrusted with the task of relocation was the mining company "Venčac" as its experts previously participated in the relocation of the Abu Simbel temple in Egypt.[7]

First idea was to leave the plaque at its position and to build the caisson around it but the calculations showed this wouldn't work. The idea of cutting the plaque in several smaller pieces in order to be moved was abandoned due to the quality of the rock of which it was made. The proposition of lifting it with the floating elevator "Veli Jože" was discarded, too. The motion of cutting the table in one piece and placing it somewhere else was rejected as the plaque would lose its authenticity.[7]

In the end it was decided to dig in a new bed into the rock 22 m (72 ft) above the plaque's original location. The plaque was then cut in one piece with the parts of the surrounding rock and road. After being cut with the cable saws, the 350 tons heavy chunk was lifted to the new bed. Works began in September 1967 and were finished in 1969.[7]

Destruction and remains

.jpg.webp)

The wooden superstructure of the bridge was dismantled by Trajan's successor, Hadrian, presumably in order to protect the empire from barbarian invasions from the north.[8] The superstructure was destroyed by fire.[2]

.jpg.webp)

The remains of the bridge reappeared in 1858 when the level of the Danube hit a record low due to the extensive drought.[2] The twenty pillars were still visible.

In 1906, the Commission of the Danube decided to destroy two of the pillars that were obstructing navigation.

In 1932, there were 16 pillars remaining underwater, but in 1982 only 12 were mapped by archaeologists; the other four had probably been swept away by water. Only the entrance pillars are now visible on either bank of the Danube,[9] one in Romania and one in Serbia.[2]

In 1979, Trajan's Bridge was added to the Monument of Culture of Exceptional Importance, and in 1983 on Archaeological Sites of Exceptional Importance list, and by that it is protected by the Republic of Serbia.

See also

- List of inscriptions in Serbia

- List of Roman bridges

- Trajan's Dacian Wars

- Constantine's Bridge (Danube)

- Luigi Ferdinando Marsigli

References

- The bridge seems to have been surpassed in length by another Roman bridge across the Danube, Constantine's Bridge, a little-known structure whose length is given at 2,437 m (Tudor 1974b, p. 139; Galliazzo 1994, p. 319). In China, the 6th century single-span Anji Bridge had a comparable span of 123 feet or 37 meters.

- Slobodan T. Petrović (18 March 2018). "Стубови Трајановог моста" [Pillars of the Trajan's Bridge]. Politika-Magazin, No. 1068 (in Serbian). pp. 22–23.

- The earliest identified Roman caisson construction was at Cosa, a small Roman colony north of Rome, where similar caissons formed a breakwater as early as the 2nd century BC: International Handbook of Underwater Archaeology, 2002.

- Fernández Troyano, Leonardo, "Bridge Engineering - A Global Perspective", Thomas Telford Publishing, 2003

- In the first century BC, Roman engineers had employed wooden caissons in constructing the Herodian harbour at Caesarea Maritima: Carol V. Ruppe, Jane F. Barstad, eds. International Handbook of Underwater Archaeology, 2002, "Caesarea" pp505f.

- Ranko Jakovljević (9 September 2017), "Srećniji od Avgusta, bolji of Trajana", Politika-Kulturni dodatak (in Serbian), p. 05

- Mikiša Mihailović (26 May 2019). "Спасавање Трајанове табле" [Preservation of the Tabula Traiana]. Politika-Magazin, No. 1130 (in Serbian). pp. 22–23.

- Opper, Thorsten (2008), Hadrian: Empire and Conflict, Harvard University Press, p. 67, ISBN 9780674030954

- Romans Rise from the Waters Archived 2006-12-05 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

- Bancila, Radu; Teodorescu, Dragos (1998), "Die römischen Brücken am unteren Lauf der Donau", in Zilch, K.; Albrecht, G.; Swaczyna, A.; et al. (eds.), Entwurf, Bau und Unterhaltung von Brücken im Donauraum, 3. Internationale Donaubrückenkonferenz, 29–30 October, Regensburg, pp. 401–409

- Galliazzo, Vittorio (1994), I ponti romani. Catalogo generale, vol. 2, Treviso: Edizioni Canova, pp. 320–324 (No. 646), ISBN 88-85066-66-6

- Griggs, Francis E. (2007), "Trajan's Bridge: The World's First Long-Span Wooden Bridge", Civil Engineering Practice, 22 (1): 19–50, ISSN 0886-9685

- Gušić, Sima (1996), "Traian's Bridge. A Contribution towards its Reconstruction", in Petrović, Petar (ed.), Roman Limes on the Middle and Lower Danube, Cahiers des Portes de Fer, vol. 2, Belgrade, pp. 259–261

- O’Connor, Colin (1993), Roman Bridges, Cambridge University Press, pp. 142–145 (No. T13), 171, ISBN 0-521-39326-4

- Serban, Marko (2009), "Trajan's Bridge over the Danube", The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 38 (2): 331–342, doi:10.1111/j.1095-9270.2008.00216.x, S2CID 110708933

- Tudor, D. (1974a), "Le pont de Trajan à Drobeta-Turnu Severin", Les ponts romains du Bas-Danube, Bibliotheca Historica Romaniae Études, vol. 51, Bucharest: Editura Academiei Republicii Socialiste România, pp. 47–134

- Tudor, D. (1974b), "Le pont de Constantin le Grand à Celei", Les ponts romains du Bas-Danube, Bibliotheca Historica Romaniae Études, vol. 51, Bucharest: Editura Academiei Republicii Socialiste România, pp. 135–166

- Ulrich, Roger B. (2007), Roman Woodworking, Yale University Press, pp. 104–107, ISBN 978-0-300-10341-0

- Vučković, Dejan; Mihajlović, Dragan; Karović, Gordana (2007), "Trajan's Bridge on the Danube. The Current Results of Underwater Archaeological Research", Istros (14): 119–130

- Ранко Јаковљевић (2009). "Трајанов мост код Кладова". Rastko.