Taiwanese Mandarin

Taiwanese Mandarin, Guoyu (Chinese: 國語; pinyin: Guóyǔ; lit. 'National Language') or Huayu (Chinese: 華語; pinyin: Huáyǔ; lit. 'Mandarin Language') refers to Mandarin Chinese spoken in Taiwan. This comprises two main forms: Standard Guoyu, the formal standard variety, and Taiwan Guoyu, its more colloquial, localized form. A large majority of the Taiwanese population is fluent in Mandarin, though many also speak Taiwanese Hokkien.

| Taiwanese Mandarin | |

|---|---|

| 臺灣華語, Táiwān Huáyǔ 中華民國國語, Zhōnghuá Mínguó Guóyǔ | |

| Pronunciation | Standard Beijing Mandarin [tʰäi˧˥wän˥xwä˧˥ɥy˨˩˦] Standard Taipei Mandarin [tʰɐɪ˧˥ʋɐn˦hʊɐ˧˥ɹ̠˔ʏ˨˩] |

| Native to | Taiwan |

Native speakers | (4.3 million cited 1993)[1] L2 speakers: more than 15 million (no date)[2] |

Sino-Tibetan

| |

| Traditional Chinese characters | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Ministry of Education (Taiwan) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| ISO 639-6 | goyu (Guoyu) |

| Glottolog | taib1240 |

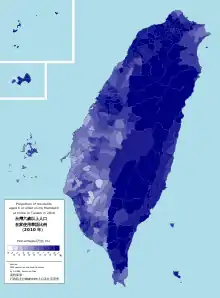

Percentage of Taiwanese aged 6 and above who spoke Mandarin at home in 2010 | |

| Taiwanese Mandarin | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 臺灣華語 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 台湾华语 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| National language of the Republic of China | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中華民國國語 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中华民国国语 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Standard Guoyu (標準國語 Biāozhǔn Guóyǔ) refers to the formal variety that serves as the official national language of the Republic of China (Taiwan). This variety is used in the education system, in official communications, and in most news media. The core of this standard variety is described in the Ministry of Education Mandarin Chinese Dictionary. The standard is based on the phonology of the Beijing dialect of Mandarin Chinese and the grammar of written vernacular Chinese.[3] Standard Guoyu closely resembles and is mutually intelligible with the Standard Mandarin (普通話, simp. 普通话, pinyin: Pǔtōnghuà) of mainland China. However, some divergences and differences exist in pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar.

Taiwan Guoyu (台灣國語 Táiwān Guóyǔ) refers to the more colloquial form of the language, namely, varieties of Mandarin used in Taiwan that diverge from Standard Guoyu. These divergences are often the result of Taiwan Guoyu incorporating influences from other languages used in Taiwan, primarily Taiwanese Hokkien. Like Standard Guoyu, Taiwan Guoyu is mutually intelligible with Putonghua. However, when compared with Standard Guoyu, Taiwan Guoyu exhibits greater differences from Putonghua.

All forms of written Chinese in Taiwan often use traditional characters alongside other Sinophone areas such as Hong Kong, Macau, and many overseas Chinese communities. This is in contrast to mainland China and Singapore, where simplified Chinese characters were adopted beginning in the 1950s and 1980s, respectively.

This article uses Taiwan Guoyu to refer to the colloquial varieties of Mandarin in Taiwan, Standard Guoyu for the prescribed standard form, Putonghua to refer to Standard mainland Chinese Mandarin, and simply Guoyu or Taiwanese Mandarin when a distinction is unnecessary.

Terms and definition

Chinese is not a single language, but a group of languages in the Sinitic branch of the Sino-Tibetan family, which includes varieties such as Mandarin, Cantonese, and Hakka. They share a common ancestry and script, Chinese characters, and among Chinese speakers they are popularly considered dialects (方言 fāngyán) of the same, overarching language. These dialects are often extremely divergent in the spoken form, however, and not mutually intelligible. Accordingly, Western linguists tend to treat them as separate languages, likening their relationship to that of English and Dutch, for example (both being West Germanic languages).[4][5]

Mandarin Chinese is a grouping of Chinese languages that includes at least eight subgroups (often also called dialects). In English, "Mandarin" can refer to any of these Mandarin dialects, which are not necessarily mutually intelligible.[6] However, the term is most commonly used to refer to Standard Chinese,[7][8] the prestige dialect.

Standard Chinese in mainland China is called Putonghua (普通话 Pǔtōnghuà, lit. 'common speech') and in the Republic of China (Taiwan) Guoyu (國語 Guóyǔ, lit. 'national language'). Both of these, as Mandarin languages, are based on the Beijing dialect of Mandarin and are mutually intelligible, but also feature various lexical, phonological, and grammatical differences.[9] There exists significant variation within Putonghua and Guoyu as well.[10] Many linguists argue that Putonghua and Guoyu are abstract, artificial standards that, strictly speaking, do not represent the native spoken language of any significant number of people.[11][12]

Some linguists have thus further differentiated between Standard Guoyu (標準國語 Biāozhǔn Guóyǔ) and Taiwan Guoyu (臺灣國語 Táiwān Guóyǔ), which refers to Mandarin as it is commonly spoken, incorporating significant influence from mutually unintelligible Southern Min Chinese dialects (namely, Hokkien).[13][14] More formal settings—such as television news broadcasts—will feature speakers using Standard Guoyu, which closely resembles mainland Putonghua, but is not generally used as a day-to-day language.[15] Not all linguists emphasize the differences between the prescribed Standard Guoyu and Guoyu as is generally spoken in Taiwan; instead, some only distinguish between relatively standard "Taiwan Guoyu/Mandarin" and "Taiwanese Guoyu/Mandarin". The former refers to Guoyu as used by those fully educated in the language, and the latter refers to an even more heavily Southern Min-influenced variety often spoken by older people who learned Guoyu only as a second language.[16] This Taiwanese Guoyu diverges greatly from standardized forms of the language and is somewhat stigmatized as uneducated.[17]

This article focuses on the features of both Standard Guoyu, particularly its relationship to Putonghua, as well as non-standard but widespread features of Mandarin in Taiwan, grouped under Taiwan Guoyu.

History and usage

Large-scale Han Chinese settlement of Taiwan began in the 17th century by Hoklo immigrants from Fujian province who spoke Southern Min languages (predominantly Hokkien), and, to a lesser extent, Hakka immigrants who spoke their respective language.[18] Taiwanese indigenous peoples already inhabited the island, speaking a variety of Austronesian languages unrelated to Chinese. In the centuries following Chinese settlement, the number of indigenous languages dropped significantly, with several going extinct, in part due to the process of sinicization.[19]

Official communications among the Han were done in Mandarin (官S Guānhuà, lit. 'official language'), but the primary languages of everyday life were Hokkien or Hakka.[20] After its defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War, the Qing dynasty ceded Taiwan to the Empire of Japan, which governed the island as an Imperial colony from 1895 to 1945. By the end of the colonial period, Japanese had become the high dialect of the island as the result of decades of Japanization policy.[20]

Under KMT rule

After the Republic of China under the Kuomintang (KMT) regained control of Taiwan in 1945, Mandarin was introduced as the official language and made compulsory in schools, despite the fact that it was rarely spoken by the local population.[21] Many who had fled the mainland after the fall of the KMT also spoke non-standard varieties of Mandarin, which may have influenced later colloquial pronunciations.[22] Wu Chinese dialects were also influential due to the relative power KMT refugees from Wu-speaking Zhejiang, Chiang Kai-shek's home province.[23]

The Mandarin Promotion Council (now called National Languages Committee) was established in 1946 by then-Chief Executive Chen Yi to standardize and popularize the usage of Mandarin in Taiwan. The Kuomintang heavily discouraged the use of Hokkien and other non-Mandarin languages, portraying them as inferior,[24] and school children were punished for speaking their native languages.[21] Guoyu was thus established as a lingua franca among the various groups in Taiwan at the expense of other, preexisting, languages.[25]

Post-martial law

Following the end of martial law in 1987, language policy in the country underwent liberalization, but Guoyu remained the dominant language. Local languages were no longer proscribed in public discourse, mass media, and schools.[26] Guoyu is still the main language of public education, with English and "mother tongue education" (母語教育 mǔyǔ jiàoyù) being introduced as subjects in primary school.[27] Greater time and resources are devoted to both Mandarin and English, which are compulsory subjects, compared to mother tongue instruction.[28]

Mandarin is spoken fluently by the vast majority of the Taiwanese population, with the exception of some of the elderly population, who were educated under Japanese rule. In the capital of Taipei, where there is a high concentration of Mainlander descendants who do not natively speak Hokkien, Mandarin is used in greater frequency and fluency than other parts of Taiwan. The 2010 Taiwanese census found that in addition to Mandarin, Hokkien was natively spoken by around 70% of the population, and Hakka by 15%.[29] A 2004 study found that Mandarin was spoken more fluently by Hakka and Taiwanese aboriginals than their respective mother tongues; Hoklo groups, on average, spoke better Hokkien, but young and middle-aged Hoklo (under 50 years old) still spoke significantly better Mandarin (with comparable levels of fluency to their usage of Hokkien) than the elderly.[30][note 1] Overall, while both national and local levels of government have promoted the use of non-Mandarin Chinese languages, younger generations generally prefer using Mandarin.[31]

Government statistics from 2020 found that 66.3% of Taiwanese residents use Guoyu as their primary language, and another 30.5% use it as a secondary language (31.7% used Hokkien as their primary language, and 54.3% used it as a secondary language).[32] Guoyu is the primary language for over 80% of people in the northern areas of Taipei, Taoyuan, and Hsinchu.[32] Youth is correlated with use of Guoyu: in 2020, over two-thirds of Taiwanese over 65 used Hokkien or Hakka as their primary language, compared with just 11% of 15–24-year-olds.[33]

Script

Guoyu employs traditional Chinese characters (which are also used in the two special administrative regions of China, Hong Kong and Macau), rather than the simplified Chinese characters used in mainland China. Literate Taiwanese can generally understand a text in simplified characters.[34]

Shorthand characters

In practice, Taiwanese Mandarin users may write informal, shorthand characters (俗字 súzì, lit. 'customary/conventional characters; also 俗體字 sútǐzì) in place of the full traditional forms. These variant Chinese characters are generally easier to write by hand and consist of fewer strokes. Often, suzi are identical to their simplified counterparts, but they may also take after Japanese kanji, or differ from both, as shown in the table below. A few shorthand characters are used as frequently as standard traditional characters, even in formal contexts, such as the tai in Taiwan, which is often written as 台, as opposed to the standard traditional form, 臺.[35]

| Shorthand | Traditional | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 会[36] | 會 | Identical to simplified 会 (huì) |

| 机[36] | 機 | Identical to simplified 机 (jī) |

| 発[36] | 發 | Identical to Japanese, cf. simplified 发 (fā) |

| 奌[36] | 點 | Differs from both simplified Chinese and Japanese 点, although 奌 is also a Japanese ryakuji shorthand variant (diǎn) |

| 転[37] | 轉 | Identical to Japanese, cf. simplified 转 (zhuàn, zhuǎn) |

| 亇[37] | 個 | Differs from both simplified Chinese 个 (gè) and Japanese 箇 or katakana ヶ |

| 対[37] | 對 | Identical to Japanese, cf. simplified 对 (duì) |

| 歺[38] | 餐 | 餐 is standard simplified as well. 歺 is formally a variant of the unrelated 歹 dǎi but is identical to the short-lived second-round simplification version of 餐.[39] (cān) |

| 咡[37] | 聽 | Unlike simplified 听, 咡 retains the radical for 'ear' (耳 tīng). |

Braille

Taiwanese braille is based on different letter assignments than Mainland Chinese braille.[40]

Zhuyin Fuhao

While pinyin is used in applications such as in signage, most Guoyu users learn phonetics through the Zhuyin Fuhao (國語注音符號 Guóyǔ Zhùyīn Fúhào, lit. Guoyu Phonetic Symbols) system, popularly called Zhuyin or Bopomofo, after its first four glyphs. Taiwan is the only Chinese-speaking polity to use the system, which is taught in schools and represents the dominant digital input method on electronic devices. It has accordingly become a symbol of Taiwanese nationalism as well.[41]

Romanization

Chinese language romanization in Taiwan somewhat differs from on the mainland, where Hanyu Pinyin is almost exclusively used.[42] A competing system, Tongyong Pinyin, was formally revealed in 1998 with the support of then-mayor of Taipei Chen Shuibian.[43] In 1999, however, the Legislative Yuan endorsed a slightly modified version of Hanyu Pinyin, creating parallel romanization schemes along largely partisan lines, with Kuomintang-supporting areas using Hanyu Pinyin, and Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) areas using Tongyong Pinyin.[43] In 2002, the Taiwanese government led by the DPP promulgated the use of Tongyong Pinyin as the country's preferred system, but this was formally abandoned in 2009 in favor of Hanyu Pinyin.[44]

In addition, various other historical romanization systems also exist across the island, with multiple systems sometimes existing in the same locality. Following the defeat of the Kuomintang in the Chinese Civil War and their subsequent retreat to Taiwan in 1945, little emphasis was placed on the romanization of Chinese characters, with the Wade-Giles system used as the default. It is still widely used for transcribing people's legal names today.[45] The Gwoyeu Romatzyh method, invented in 1928, also was in use in Taiwan during this time period, albeit to a lesser extent.[46] In 1984, Taiwan's Ministry of Education began revising the Gwoyeu Romatzyh method out of concern that Hanyu Pinyin was gaining prominence internationally. Ultimately, a revised version of Gwoyeu Romatzyh was released in 1986,[45] which was formally called the 'National Phonetic Symbols, Second Scheme'. However, this system was not widely adopted.[47]

Phonology

Standard Guoyu

Like Putonghua, both Standard and Taiwanese Guoyu are tonal. Pronunciation of many individual characters differs in the standards prescribed by language authorities in Taipei and Beijing. Mainland authorities tend to prefer pronunciations popular in Northern Mandarin areas, whereas Taiwanese authorities prefer traditional pronunciations recorded in dictionaries from the 1930s and 1940s.[48]

These character-level differences notwithstanding, Standard Guoyu pronunciation is largely identical to Putonghua, but with two major systematic differences (also true of Taiwan Guoyu):

- Erhua, the rhotacization of certain morphemes with the suffix -兒 -er, is very rare in Guoyu.[22]

- Isochrony is considerably more syllable-timed than in other Mandarin dialects (including Putonghua), which are stress-timed. Consequently, the "neutral tone" (輕聲 qīngshēng) does not occur as often, so final syllables generally retain their tone.[22]

- For example, 朋友 'friend' is pronounced péngyou in Putonghua but péngyǒu in Guoyu, with yǒu retaining its original tone.[49] This tendency to retain original tone is not present in words ending noun suffixes such as -子 -zi or -頭 -tou .

In addition, two other phenomena, while nonstandard, are extremely common across all Mandarin speakers in Taiwan, even the highly educated:[22]

- The retroflex sounds zh- [ʈ͡ʂ], ch- [ʈ͡ʂʰ], and sh- [ʂ] merge into the alveolar consonants (z- [t͡s], c- [t͡sʰ], s- [s], respectively).

- The finals -ing [iŋ] and -eng [əŋ] have largely merged into -in [in] and -en [ən], respectively.

Taiwan Guoyu

Taiwan Guoyu pronunciation is strongly influenced by Hokkien. This is especially prominent in areas where Hokkien is common, namely, in Central and Southern Taiwan. Many, though not all, of the phonological differences between Taiwan Guoyu and Putonghua can be attributed to the influence of Southern Min.

Notable phonological features of Taiwan Guoyu include:[note 2]

- The ability to produce retroflex sounds is considered a hallmark of "good" Mandarin (i.e. Standard Guoyu);[50] most non-native speakers may hypercorrect to pronounce alveolar consonants as their retroflex counterparts when attempting to speak "properly" (for example, 十三 shísān 'thirteen' as shíshān), native Taiwanese Mandarin speakers will shift retroflex to postalveolar consonants, [ʈʂ] to [dʒ], [ʈʂʰ] to [ʃ], [ʂ] to [ɹ̠̊˔], and [ʐ] to [ɹ].[50]

- f- becomes a voiceless bilabial fricative [ɸ], closer to a light 'h' in standard English (反 fǎn → 緩 huǎn)[51]

- The syllable written as pinyin: eng ([əŋ]) after labials (in pinyin, b-, f-, m-, p- and w-) is pronounced pinyin: ong ([o̞ŋ]).[52]

- The semivowel /w/ may change, rendering e.g. the surname 翁 Wēng as [ʋəŋ] rather than [wəŋ]. The deletion of /w/ also happens in colloquial Putonghua, but less frequently.[53]

- n- and l- are sometimes interchangeable, particularly preceding nasal finals (i.e. -n, -ng)[10]

- nasal finals -n and -ng tend to merge[54]

- endings -uo, -ou, and -e (when it represents a close-mid back unrounded vowel [ɤ] like in 喝 hē 'to drink') shift to Mid central vowel [ə] or merge into the Mid back rounded vowel -o [o̞][55]

- the close front rounded vowel in words such as 雨 yǔ 'rain' become unrounded, transforming into yǐ [56]

- the diphthong -ei is monophthongized into [e], as is the triphthong -ui [uei][55]

Reduction

The non-standard Taiwanese Guoyu tends to exhibit frequent, informal elision and cluster reduction when spoken.[57] For example, 這樣子 zhè yàngzi 'this way, like so' can be pronounced similar to 醬子 jiàngzi 'paste, sauce'; wherein the "theoretical" retroflex (so called because it is a feature of Standard Guoyu but rarely realized in everyday speech, as zh- is usually pronounced z-; see above section) is assimilated into the palatal glide [j].[58]

Often the reduction involves the removal of initials in compound words, such as dropping the t in 今天 jīntiān 'today' or the ch in 非常 fēicháng 'extremely, very'.[59] These reductions are not necessarily a function of speed of speech than of register, as it is more commonly used in casual conversations than in formal contexts.[58]

Tone quality

.png.webp)

.png.webp)

Like all varieties of Mandarin, Guoyu is a tonal language. Standard Mandarin as spoken in the mainland has five tones, including the neutral tone.[60] Tones in Guoyu differ somewhat in pitch and contour.

Research suggests that speakers of Guoyu articulate the second and third tones differently from the standards of Beijing Mandarin.[61] The precise nature of the tonal differences is not well attested, however, as relevant studies often lack a sufficiently large variety of speakers.[62] Tones may vary based on age, gender, and other sociolinguistic factors, and may not even be consistent across every utterance by an individual.[63]

In general, for Guoyu speakers, the second tone does not rise as high in its pitch, and the third tone does not "dip" back up from the low, creaky voice range.[64] Overall, Guoyu speakers exhibit a lower and more narrow pitch range than speakers of the Standard Mandarin of Beijing. Acoustic analysis of 33 Mandarin speakers from Taiwan in 2008 also found that for many speakers, the second tone tends to have a dipping contour more akin to that of the prescriptive third tone.[63]

Differences from mainland Putonghua

Standard pronunciations

In addition to differences in elision and influence from Hokkien, which are not features that are codified in the standard Guoyu, there are differences in pronunciation that arise from conflicting official standards in Taiwan and the mainland. These differences are primarily but not exclusively tonal.

Quantification of the extent of pronunciation differences between Guoyu and Putonghua vary, and peer-reviewed, scholarly research on the subject is scarce. Estimates from graduate-level research include a 2008 study, based on the 7,000 characters in the List of Commonly Used Characters in Modern Chinese, which found approximately 18.3% differed between Guoyu and Putonghua, and 12.7% for the 3,500 most commonly used characters.[65] A 1992 study, however, found differences in 22.5% of the 3,500 most common characters.[66]

Much of the difference can be traced to preferences of linguistic authorities on the two sides; the mainland standard prefers popular pronunciations in northern areas, whereas the Taiwanese standard prefers those documented in dictionaries in the 1930s and 1940s.[48] The Taiwanese formal standards may not always reflect actual pronunciations commonly used by native Taiwanese Mandarin speakers.[note 3]

The following is a table of relatively common characters pronounced differently in Guoyu and Putonghua in most or all contexts (Guoyu/Putonghua):[68]

|

|

|

|

Some pronunciation differences may only appear in certain words. The following is a list of examples of such differences:

- 和 'and' — hé, hàn / hé. In Guoyu, the character may be read as hàn when used as a conjunction, whereas it is always read hé in Putonghua. This pronunciation does not apply in contexts outside of 和 as a conjunction, e.g. compound words like 和平 hépíng 'peace'.[69]

- 暴露 'to expose' — pùlù / bàolù. The pronunciation bào is used in all other contexts in Guoyu.[70]

- 質量 (质量) 'quality; mass' — zhíliàng / zhìliàng. 質 is pronounced zhí in most contexts in Guoyu, except in select words like 'hostage' (人質 rénzhì) or 'to pawn' (質押 zhìyā).[71] Zhíliàng means 'mass' in both Guoyu and Putonghua, but for Guoyu speakers it does not also mean 'quality' (instead preferring 品質 pǐnzhí for this meaning).[72]

- 從容 (从容) 'unhurried, calm' — cōngróng / cóngróng. 從 cóng is only pronounced cōng in this specific word in Standard Guoyu.[73]

- 口吃 'stutter' — kǒují / kǒuchī. 吃 is only read jí when it means 'to stammer' (as opposed to 'to eat', the most common meaning).[74]

Vocabulary

Guoyu and Putonghua share a large majority of their vocabulary, but significant differences do exist.[note 4] The lexical divergence of Guoyu from Putonghua is the result of several factors, including the prolonged political separation of the mainland and Taiwan, the influence of Imperial Japanese rule on Taiwan until 1945, and the influence of Southern Min.[75] The Cross Strait Common Usage Dictionary categorizes differences as "same word, different meaning" (同名異實 tóngmíng yìshí — homonyms); "same meaning, different word" (同實異名 tóngshí yìmíng); and "Taiwan terms" (臺灣用語 Táiwān yòngyǔ) and "mainland terms" (大陸用語 dàlù yòngyǔ ) for words and phrases specific to a given side.

Same meaning, different word

The political separation of Taiwan and mainland China after the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949 contributed to many differences in vocabulary. This is especially prominent in words and phrases which refer to things or concepts invented after the split; thus, modern scientific and technological terminology often differs greatly between Putonghua and Guoyu.[76]

In computer science, for instance, the differences are prevalent enough to hinder communication between Guoyu and Putonghua speakers unfamiliar with each other's respective dialects.[76][77] Zhang (2000) selected four hundred core nouns from computer science and found that while 58.25% are identical in Standard and Taiwanese Mandarin, 21.75% were "basically" or "entirely" different.[78]

As cross-strait relations began to improve in the early 21st century, direct interaction between mainland China and Taiwan increased, and some vocabulary began to merge, especially by means of the Internet.[79] For example, the words 瓶頸 (瓶颈) píngjǐng 'bottleneck' and 作秀 zuòxiù 'to grandstand, show off' were originally unique to Guoyu in Taiwan but have since become widely used in mainland China as well.[79] Guoyu has also incorporated mainland phrases and words, such as 渠道 qúdào, meaning 'channel (of communication)', in addition to the traditional Guoyu term, 管道 guǎndào.[80]

Further examples of vocabulary that differ from between Guoyu and Putonghua include:[81]

- Internet — Taiwan, 網路 / Mainland China, 网络

- Briefcase — 公事包 / 公文包

- Bento — 便當 / 盒饭

- Software — 軟體 / 软件

- Introduction, preamble — 導言 / 导语

- To print — 列印 / 打印

Words may be formed from abbreviations in one form of Mandarin but not the other. For example, in Taiwan, bubble tea (珍珠奶茶 zhēnzhū nǎichá) is often abbreviated 珍奶 zhēnnǎi, but this is not common on the mainland.[82] Likewise, 'traffic rules/regulations' (交通規則/交通规则, jiāotōng guīzé) is abbreviated as 交规 jiāoguī on the mainland, but not in Taiwan.[83]

Same word, different meaning

Some identical terms have different meanings in Guoyu and Putonghua. There may be alternative synonyms which can be used unambiguously by speakers on both sides. Some examples include (Guoyu/Putonghua meanings):

- 油品 yóupǐn — oils, oil-based products in general / petroleum products.[84]

- 影集 yǐngjí — TV series / photo album.[85]

- 土豆 tǔdòu — peanut / potato. 馬鈴薯 (马铃薯) mǎlíngshǔ , another synonym for potato, is also used in both dialects. 花生 huāshēng, the Putonghua word for peanut, is an acceptable synonym in Guoyu.[86]

- 公車 (公车) gōngchē — bus / government or official vehicle. 公共汽車 (公共汽车) gōnggòng qìchē, lit. 'public vehicle', is an unambiguous term or bus in both dialects.[87]

- 愛人 (爱人) àirén — lover / spouse.[88]

The same word carry different connotations or usage patterns in Guoyu and Putonghua, and may be polysemous in one form of Mandarin but not the other. For example, 籠絡 (笼络) lǒngluò in Guoyu means 'to convince, win over', but in Putonghua, it carries a negative connotation[89] (cf. 'beguile, coax'). 誇張 (夸张) kuāzhāng means 'to exaggerate,' but in Taiwan, it can also be used to express exclamation at something absurd or overdone, a meaning that is not present in Putonghua.[90] Another example is 小姐 xiǎojiě, meaning 'miss' or 'young lady', regularly used to address young women in Guoyu. On the mainland, however, the word is also a euphemism for a prostitute and is therefore not used as a polite term of address.[91]

Differing usage or preference

Guoyu and Putonghua speakers may also display strong preference for one of a set of synonyms. For example, both 禮拜 lǐbài (礼拜) and 星期 xīnqqí (xīngqī in Putonghua) are acceptable words for 'week' in Guoyu and Putonghua, but 禮拜 is more common in Taiwan.[92]

Guoyu tends to preserve older lexical items that are less used in the mainland. In Taiwan, speakers may use a more traditional 早安 zǎo'ān to say 'good morning', whereas mainland speakers generally default to 早上好 zǎoshang hǎo, for instance.[91] Both words are acceptable in either dialect.

Likewise, words with the same literal meaning in either dialect may differ in register. 而已 éryǐ 'that's all, only' is common both in spoken and written Guoyu, influenced by speech patterns in Hokkien, but in Putonghua the word is largely confined to formal, written contexts.[93]

Preference for the expression of modality often differs among northern Mandarin speakers and Taiwanese, as evidenced by the selection of modal verbs. For example, Taiwanese Mandarin users strongly prefer 要 yào and 不要 búyào over 得 děi and 別 bié, respectively, to express 'must' and 'must not', compared to native speakers from Beijing. However, 要 yào and 不要 búyào are also predominantly used among Mandarin speakers from the south of the mainland. Both pairs are grammatically correct in either dialect.[94]

Words specific to Guoyu

Some words in Putonghua may not exist in Guoyu and vice versa. Authors of the Dictionary of Different Word Across the Taiwan Strait (《两岸差异词词典》) estimate there are about 2000 words unique to Guoyu, around 10% of which come from Hokkien.[79] Sometimes, Hokkien loanwords are written directly in Bopomofo (for example, ㄍㄧㄥ).

Some of these differences stem from different social and political conditions, which gave rise to concepts that were not shared between the mainland and Taiwan, e.g. 福彩 fúcǎi, a common abbreviation for the China Welfare Lottery of the People's Republic of China, or 十八趴 shíbāpā, which refers to the 18% preferential interest rate on civil servants' pension funds in Taiwan.[89] (趴 pā as "percent" is also unique to Guoyu.)[95]

Additionally, many terms unique to Guoyu were adopted from Japanese as a result of Taiwan's status as a Japanese colony during the first half of the 20th century.[75]

Particles

Modal particles convey modality, which can be understood as a speaker's attitude towards a given utterance (e.g. of necessity, possibility, or likelihood that the utterance is true).[96] Modal particles are common in Chinese languages and generally occur at the end of sentences and so are commonly called sentence-final particles or utterance-final particles.[97]

Guoyu employs some modal particles that are rare in Putonghua. Some are entirely unique to spoken, colloquial Taiwan Guoyu, and identical particles may also have different meanings in Putonghua and Guoyu.[97] Conversely, particles that are common in Putonghua — particularly northern Putonghua, such as that spoken in Beijing — are very rare in Guoyu. Examples include 唄 (呗) bei, 嚜 me, and 罷了 (罢了) bàle.[98]

啦 lā is a very common modal particle in Guoyu, which also appears in Putonghua with less frequency and always as a contraction of 了 le and 啊 a. In Guoyu, it has additional functions, which Lin (2014) broadly defines as "to mark an explicit or implicit adjustment" by the speaker to a given claim or assessment.[99] In more specific terms, this use includes expression of impatience or displeasure (a, below); an imperative, such as a suggestion or order, especially a persistent one (b), and rejection or refutation (c).[100]

Wu (2006) argues is influenced by a similar la particle in Hokkien.[101] (Unlike in Putonghua, Guoyu speakers will use 啦 lā immediately following 了 le,[102] as seen in (a).)

- (a) Impatience or displeasure

- 睡覺了啦!明天還要上課耶!

- Go to sleep already! [You] have to go to class tomorrow!

- (b) Suggestion or order

- A: 我真的吃飽了! I'm so full!

- B: 不要客氣,再吃一碗啦! Don't be so polite, have another bowl!

- (c) Rejection or refutation

- A: 他那麼早結婚,一定是懷孕了。 He married so early, it has to be [because of] a pregnancy.

- B: 不可能啦。 There's no way.

Taiwan Guoyu has functionally adopted some particles from Hokkien. For example, the particle hoⁿh[note 5] [hɔ̃ʔ] functions in Hokkien as a particle indicating a question to which the speaker expects an affirmative answer (c.f. English "..., all right?" or "..., aren't you?").[104] Among other meanings, when used in Taiwan Guoyu utterances, it can indicate that the speaker wishes for an affirmative response,[104] or may mark an imperative.[105]

In informal writing, Guoyu speakers may replace possessive particles 的 de or 之 zhī with the Japanese particle の no in hiragana (usually read as de), which serves a nearly identical grammatical role.[106] No is often used in advertising, where it evokes a sense of playfulness and fashionability,[106] and handwriting, as it is easier to write.[107] の is also used to represent the Southern Min particle ê, for which there is no standard Chinese character, and its usage as a shorthand for 的 de appears to have spread from Taiwan to other Chinese speaking regions, according to one linguist.[108]

Loan words and transliteration

Loan words may differ between Putonghua and Guoyu. Different characters or methods may also be chosen for transliteration (phonetic or semantic), and the number of characters may differ. In some cases, words may be loaned as transliterations in one dialect but not the other. Generally, Guoyu tends to imitate the form of Han Chinese names when transliterating foreign persons' names.[109][note 6]

Examples of differing transliterations (Guoyu, traditional characters / Putonghua, simplified) include:

From Taiwanese Hokkien

The terms "阿公 agōng" and "阿媽 amà" are more commonly heard than the Putonghua terms 爺爺 yéye (paternal grandfather), 外公 wàigōng (maternal grandfather), 奶奶 nǎinai (paternal grandmother) and 外婆 wàipó (maternal grandmother).

Both Standard Guoyu and Taiwan Guoyu make use of Hokkien loanwords. Some compound words or phrases may combine characters representing Hokkien and Guoyu words.[note 7]

Some local foods are usually referred by their Hokkien names.

From Japanese

Japanese in the early 20th century had a significant influence on modern Chinese vocabulary. The Japanese language saw the proliferation of neologisms to describe concepts and terms learned through contact with the West in the Meiji and Taisho eras.[115] Thus, the creation of words like 民主 minshu 'democracy', 革命 kakumei 'revolution' and 催眠 saimin 'hypnotize', which were then borrowed into Chinese and pronounced as Chinese words.[116]

Guoyu has been further influence by Japanese. As a result of Imperial Japan's 50-year rule over Taiwan until 1945, Hokkien (and Hakka) borrowed extensively from Japanese,[117] and Guoyu in turn borrowed some of these words from Hokkien, such that Japanese influence can be said to have come via Hokkien.[9] For example, the Hokkien word 摃龜 (Peh-oe-ji: kòngku; IPA: kɔŋ˥˩ku˥˥) 'to lose completely', which has been borrowed into Guoyu, originates from Japanese sukanku (スカンク, 'skunk'), with the same meaning.[118]

Grammar

The grammar of Taiwanese Mandarin is largely identical to Standard Mandarin as spoken in mainland inaCh, Putonghua. As with its lexicon and phonology, differences from Putonhua often stem from the influence of Hokkien.

Perfective 有 yǒu

To mark the perfect verbal aspect, Guoyu employs 有 (yǒu) where 了 (le) would be used in the strictly standard form of the language.[119] For instance, a Guoyu speaker may ask "你有看醫生嗎?" ("Have you seen a doctor?") whereas a Putonghua speaker would prefer "你看医生了吗?". This is due to the influence of Min grammar, which uses 有 (ū) in a similar fashion.[120] For recurring or specific events, however, both Taiwanese and Mainland Mandarin use 了, as in "你吃饭了吗?" ("Have you eaten?").

Auxiliary verbs

Another example of the influence of Hokkien grammar on Guoyu[note 8] is the use of 會 (huì) as "to be" (a copula) before adjectives, in addition to the usual meanings "would" or "will". Compare typical ways to render "Are you hot?" and "I am (not) hot" in Putonghua, Guoyu, and Taiwanese Hokkien:[121]

- Putonghua: 你熱不 (熱) ? — 我不熱。

- Guoyu: 你會不會熱? — 我不會熱。

- Hokkien: 你會熱嘸? — 我袂熱。

Compound (separable) verbs

Speakers of Guoyu may frequently avoid splitting separable verbs, a category of verb + object compound words that are split in certain grammatical contexts in standard usage.[122] For example, the verb 幫忙 bāngmáng 'to help; to do a favor', is composed of bāng 'to help, assist' plus máng 'to be busy; a favor'. The word in Guoyu can take on a direct object without separation, which is ungrammatical in Putonghua:[90] 我帮忙他 'I help him', acceptable in Guoyu, must be rendered as 我帮他个忙. This is not true of all separable verbs in Guoyu, and prescriptive texts still opt to treat these verbs as separable.[123]

Notes

- A standardized 5.00-scaled test of Mandarin ability was administered to participants. Among Minnanren (Hoklo) the mean was 4.81 for young (under 31 years old) participants, 4.61 for middle aged participants (31–50), and 3.24 for the elderly (>50). The mean score for mainland descendants as a whole was 4.90.

- Note that not all of these features may be present in all speakers at all times.

- For example, the Ministry of Education standards dictate that some words (e.g. 熱鬧 rènào, 認識 rènshì, 衣服 yīfú, 力量 lìliàng) be pronounced with the second character in neutral tone, in contrast to how most Taiwanese speakers of Mandarin actually say them.[67]

- Chinese Wikipedia maintains a more extensive table of vocabulary differences between Taiwan, Macau, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Singapore and mainland China.

- The Ministry of Education gives the original character for hoⁿh as 乎,[103] a particle common in Classical Chinese.

- Barack Obama is thus referred to as Ōubāmǎ 歐巴馬 as opposed to Àobāmǎ 奥巴马 in the mainland. Ōu is a common Han surname, while Ào is not (see list of common Chinese surnames).

- Wu and Su (2014) give the example of "逗热闹" 'to join in the fun' in a 2014 Liberty Times headline. The Guoyu phrase is 凑熱鬧 còu rènào; the headline substituted the verb 凑 còu for the Hokkien verb 逗 (dòu, read tàu in Hokkien).[113] The native Hokkien word is 逗鬧熱 (Pe̍h-ōe-jī: tàu‑lāu‑jia̍t) (also written 鬥鬧熱)[114]

- Neither Yang (2007) nor Sanders (1992) explicitly delineate between standard and nonstandard Guoyu. While the usage of 會 described here is heavily influenced by Southern Min, it is still used in official sources; for example, refer to the Ministry of Education's dictionary entry for 會, which includes an example sentence 「他會來嗎?」(cf. Putonghua "他來不來?).

Citations

- Mandarin Chinese (Taiwan) at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- Mandarin Chinese (Taiwan) at Ethnologue (14th ed., 2000).

- Chen 1999, p. 22.

- DeFrancis 1984, p. 56. "To call Chinese a single language composed of dialects with varying degrees of difference is to mislead by minimizing disparities that according to Chao are as great as those between English and Dutch."

- See Mair for an overview of the terminology and debate: Mair, Victor H. (September 1991). "What Is a Chinese "Dialect/Topolect"? Reflections on Some Key Sino-English Linguistic Terms". Sino-Platonic Papers (29). Retrieved 13 March 2022.

- Szeto, Ansaldo & Matthews 2018.

- Weng 2018, p. 613. "...in common usage, 'Mandarin' or 'Mandarin Chinese' usually refers to China's standard spoken language. In fact, I would argue that this is the predominant meaning of the word."

- Szeto 2019.

- Bradley 1991, p. 314.

- Chen 1999, p. 48.

- Her 2009, p. 377. "國語:教育部依據北京話所頒定的標準語,英文是Standard Mandarin,其內涵與北京話相似。但只是死的人為標準,並非活的語言。" ["Guoyu: The standard language determined by the Ministry of Education based on the Beijing dialect, with which it is similar. Called Standard Mandarin in English. It is a dead, artificial standard, and not a living language.]

- Sanders 1987.

- Shi & Deng 2006, p. 376. "標準國語"指用於正規的書面語言以及電視廣播中的通用語,……和大陸的普通話基本一致。"台灣國語"指在台灣三十歲以下至少受過高中教育的台灣籍和大陸籍人士所說的通用語,也就是因受閩南話影響而聲、韻、調以及詞彙、句法方面與標準普通話產生某些差異的語言。 ["'Standard Mandarin' refers to the language used in formal writing and television broadcasts, which in essence is Northern Mandarin absent more extreme dialect elements and features ... largely identical to Putonghua. 'Taiwan Mandarin' is the common language spoken by Taiwanese and mainland descendants in Taiwan under thirty who have received at least a high school education. The influence of Southern Min has produced differences from standard Putonghua in onsets and rimes, tone, vocabulary, and syntax."]

- Brubaker 2003. Brubaker refers to the standard form as Standard Mandarin, and the basilectal form as "Taiwan-guoyu".

- Shi & Deng 2006, p. 372–373.

- Fon, Chiang & Cheung 2004, p. 250; Hsu 2014.

- Hsu 2014.

- Scott & Tiun 2007.

- Zeitoun 1998, p. 51.

- Scott & Tiun 2007, p. 55.

- Scott & Tiun 2007, p. 57.

- Chen 1999, p. 47.

- Cheng 1985, p. 354; Her 2009.

- Su 2014.

- Yeh, Chan & Cheng 2004.

- Scott & Tiun 2007, p. 58.

- Scott & Tiun 2007, p. 60.

- Scott & Tiun 2007, p. 64.

- 99年人口及住宅普查 [2010 Population and Household Census] (PDF) (Report) (in Chinese (Taiwan)). Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics (行政院主計總處). September 2012. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- Yeh, Chan & Cheng 2004, pp. 86–88.

- Scott & Tiun 2007, pp. 59–60; Yap 2017.

- 109 年人口及住宅普查初步統計結果 [2021 Population and Residence Census Preliminary Statistics] (PDF) (Report) (in Chinese). Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics. 31 August 2021. p. 4. Retrieved 27 February 2022. 6歲以上本國籍常住人口計2,178.6 萬人,主要使用語言為國語者占 66.3%,閩南語占 31.7%;主要或次要使用國語者占 96.8%,閩南語者占86.0%,客語者占 5.5%,原住民族語者占 1.1%。 [There are 21,786,000 permanent resident nationals over the age of six. 66.3% primarily use Guoyu, and 31.7% Southern Min [i.e. Hokkien]. 96.8% use Guoyu either primarily or secondarily, 86.0% use Southern Min, 5.5% use Hakka, and 1.1% use aboriginal languages.]

- Lin, If (30 September 2021). "最新普查:全國6成常用國語,而這6縣市主要用台語" [Newest Census: 60% Nationally Use Guoyu Regularly, But These 6 Cities and Counties Use Taiyu]. The News Lens 關鍵評論網 (in Chinese). Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- Wiedenhof 2015, p. 401.

- Wang et al. 2015, p. 251.

- Su, Dailun (12 April 2006). "基測作文 俗體字不扣分 [Basic Competence Test will not penalize nonstandard characters]". Apple Daily (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 8 November 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- Weng, Yunqian (19 April 2021). "聽寫成「咡」、點寫成「奌」?網揭「台式簡體」寫法超特別:原來不只我這樣". Daily View (網路溫度計). Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- He, Zewen (10 September 2019). "簡體字破壞中華文化?最早的「漢字簡化」,其實是國民黨提出來的". Crossing (換日線). Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- "歺". Recompiled Guoyu Dictionary, Revised Edition [《重編國語辭典修訂本》] (in Chinese). Taipei: Ministry of Education of the Republic of China. 2015.

- "Braille for Chinese". Omniglot. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- Huang 2019.

- Lin 2015.

- Lin 2015, p. 200.

- Shih, Hsiu-chuan (18 September 2008). "Hanyu Pinyin to be standard system in 2009". Taipei Times. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- Lin 2015, p. 199.

- Lin 2015, p. 199; Chiung 2001, p. 33.

- Chiung 2001, p. 25.

- Chen 1999, pp. 46–47.

- "朋友", Cross Straits Dictionary [兩岸詞典], Taipei: Ministry of Education of the Republic of China. Accessed 24 December 2021.

- Kubler 1985, p. 159.

- Kubler 1985, p. 157.

- Chen 1999, p. 48; Kubler 1985, p. 159.

- Wiedenhof 2015, p. 46.

- Hsu & Tse 2007; Bradley 1991, p. 315.

- Kubler 1985, p. 160.

- Kubler 1985, p. 160; Chen 1999, p. 47.

- Chung 2006; Cheng & Xu 2013.

- Chung 2006, p. 71.

- Chung 2006, pp. 75–77.

- Wiedenhof 2015, pp. 12–16.

- Fon, Chiang & Cheung 2004, p. 250.

- Sanders 2008, p. 88.

- Sanders 2008, pp. 104–105.

- Fon, Chiang & Cheung 2004, pp. 250–51.

- Nan 2008, p. 65. 在《現代漢語常用字表》3500 字中,讀音差異的有 444 處,佔 12.7%。 在《現代漢語通用字表》7000 字中,讀音差異的有 1284 處,佔 18.3%。 ["Among the 7000 characters in List of Commonly Used Characters in Modern Chinese, 1284, or 18.3%, had different readings. Among the 3500 characters in the List of Frequently Used Characters in Modern Chinese, 444, or 12.7%, had different readings."]

- Chen 1999, pp. 46–47; Li 1992.

- "熱「ㄋㄠˋ」改「ㄋㄠ˙」 教育部字典被網罵:演古裝劇?" ["'Rènào' to 'rènao'—Ministry of Education Dictionary criticized online: Are they pretending to be in some period piece?"]. ETtoday (in Chinese). 27 February 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- Per the respective Cross-Strait Common Vocabulary Dictionary entries in the Taiwanese Ministry of Education's dictionary website. Each character is present on the List of Most Frequently Used Characters in Modern Chinese (现代汉语常用字表), also available on Wikisource in translation here.

- "和". Cross-Strait Common Vocabulary Dictionary [兩岸常用詞典] (in Chinese). Taipei: General Association of Chinese Culture. 2016.

- "暴露". Cross-Strait Common Vocabulary Dictionary [兩岸常用詞典] (in Chinese). Taipei: General Association of Chinese Culture. 2016.

- "質". Cross-Strait Common Vocabulary Dictionary [兩岸常用詞典] (in Chinese). Taipei: General Association of Chinese Culture. 2016.

- Lu, Wei (20 February 2010). "詞彙研究所-質量 vs.品質". 中國時報 [China Times] (in Chinese). Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- "從". Cross-Strait Common Vocabulary Dictionary [兩岸常用詞典] (in Chinese). Taipei: General Association of Chinese Culture. 2016.

- "吃". Cross-Strait Common Vocabulary Dictionary [兩岸常用詞典] (in Chinese). Taipei: General Association of Chinese Culture. 2016.

- Chen 1999, pp. 106–107.

- Yao 2014.

- Zhang 2000, p. 38. 随着大陆与台湾、香港、澳门 ... 的科技交流、商贸活动的日益频繁,人们越来越感到海峡两岸计算机名词(以下简称两岸名词)的差异,已成为一个不小的障碍,影响着正常的业务工作。 ["With the growing frequency of scientific and technological exchange and commerce among the mainland and Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau ... people increasingly feel that the differences in computer terminology (hereafter referred to as cross-strait terms) on both sides of the Taiwan Strait have become a sizable hindrance affecting normal work."]

- Zhang 2000, p. 40. 通过分析,得出了各类名词的数量及其比例关系:完全相同名词占总数58.25%,基本相同名词占总数20%,基本不同名词占总数10.25%,完全不同名词占总数11.5%。 ["Through analysis [I] drew out the number and proportion of various nouns: identical nouns account for 58.25% of the total, basically identical nouns for 20% of the total, basically different nouns for 10.25% of the total, and entirely different nouns for 11.5% of the total."]

- Li 2015, p. 344.

- Chien, Amy Chang (22 September 2017). ""项目"、"视频":台湾人不会讲的中国话" ['Xiangmu', 'Shipin': The Chinese that Taiwanese Can't Speak]. New York Times (in Simplified Chinese).

- "同實異名". Cross-Strait Common Vocabulary Dictionary [兩岸常用詞典] (in Chinese). Taipei: General Association of Chinese Culture. 2016.

- Zhou & Zhou 2019, p. 212.

- Zhou & Zhou 2019, p. 213.

- "油品". Cross-Strait Common Vocabulary Dictionary [兩岸常用詞典] (in Chinese). Taipei: General Association of Chinese Culture. 2016.

- "影集". Cross-Strait Common Vocabulary Dictionary [兩岸常用詞典] (in Chinese). Taipei: General Association of Chinese Culture. 2016.

- "土豆". Cross-Strait Common Vocabulary Dictionary [兩岸常用詞典] (in Chinese). Taipei: General Association of Chinese Culture. 2016.

- "公車". Cross-Strait Common Vocabulary Dictionary [兩岸常用詞典] (in Chinese). Taipei: General Association of Chinese Culture. 2016.

- "愛人". Cross-Strait Common Vocabulary Dictionary [兩岸常用詞典] (in Chinese). Taipei: General Association of Chinese Culture. 2016.

- Li 2015, p. 342.

- Li 2015, p. 343.

- "两岸词汇存差异 对照交流增意趣". Xinhua (in Chinese). 18 January 2016. Archived from the original on 22 August 2021. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- Wiedenhof 2015, p. 280.

- Kubler 1985, p. 171.

- Sanders 1992, p. 289.

- "趴". Cross-Strait Common Vocabulary Dictionary [兩岸常用詞典] (in Chinese). Taipei: General Association of Chinese Culture. 2016.

- Herrmann 2014.

- Lin 2014.

- Wu 2006.

- Lin 2014, p. 122.

- Wu 2006, pp. 24–26.

- Wu 2006, p. 16.

- Wu 2006, pp. 33.

- "乎", Taiwanese Minnan Dictionary [臺灣閩南語辭典], Ministry of Education of the Republic of China, Taipei.

- Wu 2006, p. 61.

- Wu 2006, pp. 62–63.

- Chung 2001.

- Hsieh & Hsu 2006, p. 63.

- Cook 2018, p. 10. "Another factor favoring its widespread acceptance, at least in Taiwan, is that since there is no Mandarin Chinese cognate for the Southern Min attributive or possessive morpheme, ê, there is no obvious choice of Modern Standard Chinese character to represent this grammatical morpheme when writing Southern Min. This, coupled with the pervasive influence of Japanese culture in Taiwan from the period of colonization through to the present, may well have been a sufficient consideration to ensure the linguistic success of の de/ê in Taiwan, from whence it seems to be spreading to other Chinese speaking regions."

- Wang, Yinquan (25 December 2012). "两岸四地外国专名翻译异同趣谈" [An Interesting Look at Foreign Proper Noun Transliteration in China, Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan]. China Daily. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- Zhou & Zhou 2019, p. 215.

- Wang 2012.

- Zhou & Zhou 2019.

- Wu & Su 2014.

- "鬥鬧熱". Dictionary of Frequently-Used Taiwan Minnan [《臺灣閩南語常用詞辭典》] (in Chinese). Taipei: Ministry of Education of the Republic of China. 2011.

- Zhao 2006, pp. 307–311.

- Zhao 2006, p. 312.

- Yao 1992.

- Yao 1992, pp. 337, 358–59.

- Tan 2012, p. 2.

- Tan 2012, pp. 5–6.

- Yang 2007, pp. 117–119; Sanders 1992.

- Diao 2016.

- Teng, Shou-Hsin, ed. (4 November 2021). 當代中文課程 教師手冊1 [A Course in Contemporary Chinese, Teacher's Manual 1] (in Chinese) (2nd ed.). Taipei: 國立臺灣師範大學國語教學中心 [The Mandarin Training Center of National Taiwan Normal University]. p. 22. ISBN 9789570859737. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

離合詞的基本屬性是不及物動詞... 當然,在臺灣已經有些離合詞,如:「幫忙」,傾向於及物用法。因為仍不穩定,教材中仍以不及物表現為規範。

[A fundamental attribute of separable verbs is their intransivity ... of course, in Taiwan there are some separable verbs, such as bangmang, that tend to be transitive. As this [usage] is still unstable, the teaching materials still use the intransitive as the standard.]

References

- Bradley, David (1991). "Chinese as a pluricentric language". In Clyne, Michael (ed.). Pluricentric Languages: Differing Norms in Different Nations. De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 305–324. doi:10.1515/9783110888140.305. ISBN 9783110128550. Retrieved 25 August 2021.

- Brubaker, Brian Lee (2003). The Normative Standard of Mandarin in Taiwan: An Analysis in Variation of Metapragmatic Discourse (PDF) (Ph.D. thesis). University of Pittsburgh. ISBN 978-1-2677-6168-2.

- Cheng, Robert L. (1985). "A Comparison of Taiwanese, Taiwan Mandarin, and Peking Mandarin". Language. 61 (2): 352–377. doi:10.2307/414149. ISSN 0097-8507. JSTOR 414149.

- Cheng, Chierh; Xu, Yi (December 2013). "Articulatory limit and extreme segmental reduction in Taiwan Mandarin". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 134 (6): 4481–4495. Bibcode:2013ASAJ..134.4481C. doi:10.1121/1.4824930. PMID 25669259.

- Chen, Ping (1999). Modern Chinese: History and Sociolinguistics. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64572-0.

- Chiung, Wi-vun Taiffalo (2001). "Romanization and Language Planning in Taiwan" (PDF). The Linguistic Association of Korea Journal. 9 (1): 15–43. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- Chung, Karen Steffen (2001). "Some Returned Loans: Japanese Loanwords in Taiwan Mandarin" (PDF). In McAuley, T.E. (ed.). Language Change in East Asia. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon. pp. 171–73. ISBN 0700713778. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- Chung, Karen Steffen (January 2006). "Contraction and Backgrounding in Taiwan Mandarin" (PDF). Concentric: Studies in Linguistics. 32 (1): 69–88. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- Cook, Angela (December 2018). "A typology of lexical borrowing in Modern Standard Chinese". Lingua Sinica. 4 (1). doi:10.1186/s40655-018-0038-7. S2CID 96453867.

- DeFrancis, John (1984). The Chinese Language: Fact and Fantasy. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1068-9.

- Diao, Yanbin (2016). "海峡两岸离合词使用情况对比考察" [A Comparative Study of Separable Verbs Usage Across The Strait]. 海外华文教育 [Oversease Chinese Education] (in Simplified Chinese) (4). doi:10.14095/j.cnki.oce.2016.04.001.

- Fon, Janice; Chiang, Wen-Yu; Cheung, Hintat (2004). "Production and Perception of the Two Dipping Tones (Tone 2 and Tone 3) in Taiwan Mandarin / 台湾地区国语抑扬调 (二声与三声) 之发声与听辨". Journal of Chinese Linguistics. 32 (2): 249–281. ISSN 0091-3723. JSTOR 23756118. Retrieved 13 March 2022.

- Li, Qingmei (1992). "海峡两岸字音比较" [Comparison of Cross-straits Character Pronunciation]. 语言文字应用 [Applied Linguistics]. 3: 42–48.

- Lin, Peiyin (December 2015). "Language, Culture, and Identity: Romanization in Taiwan and Its Implications". Taiwan Journal of East Asian Studies. 12 (2). doi:10.6163/tjeas.2015.12(2)191.

- Her, One-Soon (2009). "語言與族群認同:台灣外省族群的母語與台灣華語談起" [Language and Group Identity: On Taiwan Mainlanders’ Mother Tongues and Taiwan Mandarin.] (PDF). Language and Linguistics (in Chinese). 10 (2): 375–419. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-08-20. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- Herrmann, Annika (2014). Modal and Focus Particles in Sign Languages: A Cross-linguistic Study. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 78–79. ISBN 9781614511816.

- Hsieh, Shelley Ching-yu; Hsu, Hui-li (2006). "Japan Mania and Japanese Loanwords in Taiwan Mandarin: Lexical Structure and Social Discourse / 台灣的哈日與日語借詞:裡會面觀和詞彙影響". Journal of Chinese Linguistics. 34 (1): 44–79. ISSN 0091-3723. JSTOR 23754148. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- Hsu, Hui-ju (1 July 2014). "在族群與語言接觸下形成的台灣華語─從聲學分析的結果看起" [Taiwan Mandarin, a Mandarin Variety Formed under the Social and Language Contact between Various Chinese Dialects and Their Speakers]. Language and Linguistics. 15 (5): 635–662. doi:10.1177/1606822X14528638.

- Hsu, Hui-Ju; Tse, John Kwock-Ping (1 January 2007). "Syllable-Final Nasal Mergers in Taiwan Mandarin-Leveled but Puzzling". Concentric: Studies in Linguistics. 33 (1): 1–18. doi:10.6241/concentric.ling.200701_33(1).0001.

- Huang, Karen (3 July 2019). "Language ideologies of the transcription system Zhuyin fuhao: a symbol of Taiwanese identity". Writing Systems Research. 11 (2): 159–175. doi:10.1080/17586801.2020.1779903. S2CID 222110820.

- Kubler, Cornelius C. (1985). "The Influence of Southern Min on the Mandarin of Taiwan". Anthropological Linguistics. 27 (2): 156–176. ISSN 0003-5483. JSTOR 30028064.

- Li, Xingjian (1 January 2015). "两岸差异词及两岸差异词词典的编纂 —— 《两岸差异词词典》编后感言" [Different Words Across the Taiwan Strait and the Compilation of A Dictionary of Different Word Across the Taiwan Strait]. Global Chinese (in Simplified Chinese). 1 (2): 339–353. doi:10.1515/glochi-2015-1015.

- Lin, Chin-hui (2014). Utterance-final Particles in Taiwan Mandarin: Contact, Context, and Core Functions. Utrecht: LOT. ISBN 978-94-6093-149-9.

- Nan, Jihong (June 2008). 兩岸語音規範標準之差異探析 ─ 以《現代漢語通用字表》為範疇 [A Study of the Distinction of Pronunciation Standards between Taiwan and Mainland China] (PDF) (Master's thesis) (in Chinese). National Taiwan Normal University [國立台灣師範大學]. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 August 2021.

- Sanders, Robert M. (November 1987). "The Four Languages of 'Mandarin'". Sino-Platonic Papers (4). Retrieved 13 March 2022.

- Sanders, Robert M. (1992). "The Expression of Modality in Peking and Taipei Mandarin / 關於北京話和台北國語中的情態表示". Journal of Chinese Linguistics. 20 (2): 289–314. ISSN 0091-3723. JSTOR 23753908.

- Sanders, Robert (2008). Chan, Marjorie K.M.; Kang, Hana (eds.). Tonetic Sound Change in Taiwan Mandarin: The Case of Tone 2 and Tone 3 Citation Contours (PDF). 20th North American Conference on Chinese Linguistics. Vol. 1. Columbus: Ohio State University. pp. 87–107.

- Scott, Mandy; Tiun, Hak-khiam (23 January 2007). "Mandarin-Only to Mandarin-Plus: Taiwan". Language Policy. 6 (1): 53–72. doi:10.1007/s10993-006-9040-5. S2CID 145009251.

- Shi, Feng; Deng, Dan (2006). 普通話與台灣國語的語音對比 [Phonetic Comparison of Putonghua and Taiwan Guoyu]. In He, Da'an; Zhang, Hongnian; Pan, Wuyun; Wu, Fuxiang (eds.). 山高水長:丁邦新先生七秩壽慶論文集 [High Mountains and Long Rivers: Essays Celebrating the 70th Birthday of Pang-hsin Ting] (PDF) (in Chinese). Taipei: Academia Sinica Institute of Linguistics. ISBN 978-986-00-7941-8. OCLC 137224557.

- Su, Jinzhi (21 January 2014). "Diglossia in China: Past and Present". In Árokay, Judit; Gvozdanović, Jadranka; Miyajima, Darja (eds.). Divided languages?: Diglossia, Translation and The Rise of Modernity in Japan, China, and the Slavic World. ISBN 978-3-319-03521-5.

- Szeto, Pui Yiu; Ansaldo, Umberto; Matthews, Stephen (28 August 2018). "Typological variation across Mandarin dialects: An areal perspective with a quantitative approach". Linguistic Typology. 22 (2): 233–275. doi:10.1515/lingty-2018-0009. S2CID 126344099.

- Szeto, Pui-Yiu (5 October 2019). "Mandarin dialects: Unity in diversity". Unravelling Magazine. Retrieved 25 August 2021.

- Tan, Le-kun 陳麗君 (2012). "華語語言接觸下的「有」字句" [The Usage of Taiwanese U and Mandarin You as a Result of Language Contact between Taiwanese and Taiwan Mandarin]. 台灣學誌 [Monumenta Taiwanica] (5): 1–26.

- Wang, Boli; Shi, Xiaodong; Chen, Yidong; Ren, Wenyao; Yan, Siyao (March 2015). "语料库语言学视角下的台湾汉字简化研究" [On the Simplification of Chinese Characters in Taiwan: A Perspective from Corpus Linguistics]. 北京大学学报(自然科学版) [Acta Scientiarum Naturalium Universitatis Pekinensis] (in Chinese). 51 (2). doi:10.13209/j.0479-8023.2015.043.

- Weng, Jeffrey (2018). "What is Mandarin? The social project of language standardization in early Republican China". The Journal of Asian Studies. 59 (1): 611–633. doi:10.1017/S0021911818000487.

- Wiedenhof, Jeroen (2015). A grammar of Mandarin. Amsterdam Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 978-90-272-1227-6. OCLC 919452392.

- Wu, I-Peh (2006). 當代台灣國語語氣詞之研究---從核心語義和語用功能的角度探討 [The Utterance-Final Particles of Contemporary Taiwanese Mandarin---From the perspective of Core Meaning and Pragmatic Function] (Master's thesis). National Taiwan Normal University.

- Wu, Xiaofang; Su, Xinchun (2014). "台湾国语中闽南方言词汇的渗透与吸收" [The Penetration and Assimilation of Southern Min Words in Taiwan Guoyu] (PDF). 东南学术 [Southeast Academic Research] (in Chinese) (1): 240. Retrieved 13 March 2022.

- Yao, Rongsong (June 1992). "臺灣現行外來語的問題" [Survey on the Problem of Contemporary Loan Words in the Languages Spoken in Taiwan]. Journal of National Taiwan Normal University (in Chinese). 37: 329–362. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- Yao, Qian (September 2014). "Analysis of Computer Terminology Translation Differences between Taiwan and Mainland China". Advanced Materials Research. 1030–1032: 1650–1652. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.1030-1032.1650. S2CID 136508776.

- Yang, Yici (July 2007). "臺灣國語「會」的用法" [The Usage of 'Hui' in Taiwan Guoyu] (PDF). 遠東通識學報 [Journal of Far East University General Education] (in Chinese). Tainan, Taiwan: Far East University (1): 109–122. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-05-16. Retrieved 2021-05-16.

- Yap, Ko-hua (December 2017). "臺灣民眾的家庭語言選擇" [Taiwanese People's Household Language Choice] (PDF). 臺灣社會學刊 [Taiwanese Journal of Sociology] (in Chinese) (62): 59–111. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Yeh, Hsi-nan; Chan, Hui-chen; Cheng, Yuh-show (2004). "Language Use in Taiwan: Language Proficiency and Domain Analysis" (PDF). Journal of Taiwan Normal University: Humanities and Social Sciences. 49 (1): 75–108. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- Zeitoun, Elizabeth (1998). "Taiwan's Aboriginal Languages: A linguistic assessment". China Perspectives (20): 45–52. ISSN 2070-3449.

- Zhang, Wei (2000). "海峡两岸计算机名词异同浅析" [Analyses about the Similarities and Differences of Computer Terms Used in Two Sides of Taiwan Straits] (PDF). 中国科技术语 中国科技术语 [China Terminology]. 4 (2): 38–42. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- Zhao, Jian (2006). "Japanese Loanwords in Modern Chinese / 現代漢語的口語外來語". Journal of Chinese Linguistics. 34 (2): 306–327. ISSN 0091-3723. JSTOR 23754127.

- Zhou, Jianjiao; Zhou, Shu (2019). "A Study on Differences Between Taiwanese Mandarin and Mainland Mandarin in Vocabulary". Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Culture, Education and Economic Development of Modern Society (ICCESE 2019). Moscow, Russia: Atlantis Press: 212–215. doi:10.2991/iccese-19.2019.48. ISBN 978-94-6252-698-3. S2CID 150304541.