Taliesin (studio)

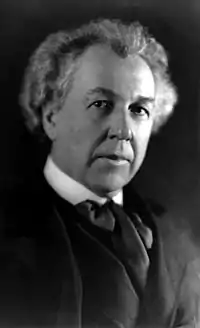

Taliesin (/ˌtæliˈɛsɪn/), sometimes known as Taliesin East, Taliesin Spring Green, or Taliesin North after 1937, was the estate of American architect Frank Lloyd Wright. An extended exemplar of the Prairie School of architecture, it is located 2.5 miles (4.0 km) south of the village of Spring Green, Wisconsin, United States. The 600-acre (240 ha) property was developed on land that originally belonged to Wright's maternal family.

| Taliesin | |

|---|---|

Taliesin III's drafting studio (left) and living quarters (right) as seen from the crown of its hill | |

Interactive map showing Taliesen’s location | |

| Location | 5607 County Road C Spring Green, 53588 in Iowa County, Wisconsin, United States |

| Coordinates | 43°08′28″N 90°04′14″W |

| Built | 1911–1959 |

| Visitors | 25,000[1] (in 2009) |

| Governing body | Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation |

| Criteria | Cultural: (ii) |

| Designated | 2019 (43rd session) |

| Part of | The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright |

| Reference no. | 1496-003 |

| Region | Europe and North America |

| Designated | March 14, 1973 |

| Reference no. | 73000081[2] |

| Designated | January 7, 1976[2] |

Location of Taliesin in Wisconsin  Taliesin (studio) (the United States) | |

With a selection of Wright's other work, Taliesin became a listed World Heritage Site in 2019, under the title, "The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright".

Introduction

Wright designed the main Taliesin home and studio after leaving his first wife and home in Oak Park, Illinois with his mistress, Mamah Borthwick. The design of the original building was consistent with the design principles of the Prairie School, emulating the flatness of the plains and the natural limestone outcroppings of Wisconsin's Driftless Area. The structure (which included agricultural and studio wings) was completed in 1911. The name, Taliesin, meaning 'shining-brow' in Welsh, was initially used for this building (built on and into the brow of a hill or ridge) and later for the entire estate.

Over the course of Wright's residency two major fires led to significant alterations, and these stages of the residence are now referred to as Taliesin I, II, and III. Wright rebuilt the Taliesin residential wing in 1914 after a disgruntled employee set fire to the living quarters and murdered Borthwick and six others. This second version was used only sparingly by Wright as he worked on projects abroad. He returned to the house in 1922 following completion of the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. A fire caused by electrical problems destroyed the living quarters in April 1925. The third version of the living quarters was constructed by Wright by late 1925.

In 1927, financial problems caused a foreclosure on the building by the Bank of Wisconsin. Wright was able to reacquire the building with the financial help of friends and reoccupy it by November 1928. In 1932, he established a fellowship for architectural students at the estate. Taliesin III was Wright's home for the rest of his life, although he began to winter at Taliesin West in Scottsdale, Arizona upon its completion in 1937. Many of Wright's acclaimed buildings were designed here, including Fallingwater, "Jacobs I" (the first Wright-designed residence of Herbert and Katherine Jacobs), the Johnson Wax Headquarters, and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Wright was also an avid collector of Asian art and used Taliesin as a storehouse and private museum.

Wright left Taliesin and the 600-acre Taliesin Estate to the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation (founded by him and his third wife in 1940) upon his death in 1959. This organization oversaw renovations to the estate until late 1992 upon the founding of Taliesin Preservation, Inc., a nonprofit organization dedicated to preserving the building and estate in Wisconsin. The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation and Taliesin Preservation operate numerous public programs on the campus, and the farm is still in use today by tenant farmers.

The Taliesin estate was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1976, and the Taliesin structure was inscribed as part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site in July 2019.

Four other Wright-designed buildings on the estate are National Historic Landmarks (but not part of the UNESCO designation, which is just reserved for the Taliesin structure). These are the Romeo and Juliet Windmill, designed by Wright in 1896; Tan-y-Deri, the home he designed for Jane and Andrew Porter, his sister, and brother-in-law, in 1907; the Hillside Home School, originally designed in 1901 for his aunts' school; and Midway Barn, a farming facility he began c. 1920.

Location

Jones Valley, the Wisconsin River valley in which Taliesin sits, was formed during Pre-Illinoian glaciation. This region of North America, known as the Driftless Area, was totally surrounded by ice during Wisconsin glaciation, but the area itself was not glaciated. The result is an unusually hilly landscape with deeply carved river valleys.[3][4]

The valley, approximately 2.5 miles (4.0 km) south of the village of Spring Green, Wisconsin,[5] was originally settled by Frank Lloyd Wright's maternal grandfather, Richard Lloyd Jones. Jones had emigrated with his family from Wales, moving to the Town of Ixonia in Jefferson County, Wisconsin. In 1858, Jones and the family moved from Ixonia to this part of Wisconsin to start a farm.[6] By the 1870s, Richard's sons had taken over operation of the farm, and they invited Wright to work during summers as a farmhand.[7]

Wright's aunts Jane and Ellen C. Lloyd Jones (known as Jennie and Nell) began a co-educational school, the Hillside Home School, in the family valley in 1887 and let Wright design the building; this was Wright's first independent commission. In 1896, Wright's aunts again commissioned Wright, this time to build a windmill. The resulting Romeo and Juliet Windmill was unorthodox but stable. In the winter of 1900, Wright compiled a portfolio of photographs he took of the surrounding area for a promotional brochure for the Hillside School.

In 1901, Wright was again commissioned by Jennie and Nell to design another structure. Unsatisfied with his original design for the Hillside School, Wright designed the Hillside Home School in 1901 in the Prairie Style.[7] Wright later sent several of his children to receive an education at the school.[8] Wright's final commission on the farm was a house for his sister Jane Porter in 1907. Tan-Y-Deri, Welsh for "Under the Oaks", was a design based on his recent Ladies Home Journal article "A Fireproof House for $5000." The family, their ideas, religion, and ideals, greatly influenced the young Wright, who later changed his middle name from Lincoln (in honor of Abraham Lincoln) to Lloyd in deference to his mother's family.[7]

Etymology

When Wright decided to construct a home in this valley, he chose the name of the Welsh bard Taliesin, whose name means "shining brow" or "radiant brow". Wright learned of the poet through Richard Hovey's Taliesin: A Masque,[9] a story about an artist's struggle for identity.[10] The Welsh name also suited Wright's roots, as the Lloyd Joneses gave Welsh names to their properties.[11] The hill upon which Taliesin was built was a favorite from Wright's youth; he saw the house as a "shining brow" on the hill, [12][13] in hope of a place of refuge "but I had forgotten grandfather Isiah´s punishments and beatings" (FLW Autobiography).[14] Although the name was originally only applied to the house, Wright later used the term to refer to the entire property. Wright and others used roman numerals to distinguish the three versions of the house.[15]

Early history

From 1898 to 1909, architect Frank Lloyd Wright lived and worked out of his home and studio in Oak Park, Illinois. In Oak Park, Wright had developed his concept of Prairie School architecture, designing houses primarily for local clients. In 1903, Wright began designing a home for Edwin Cheney, but quickly took a liking for Cheney's wife. Wright and Mamah Borthwick Cheney began an affair and separated from their spouses in 1909.[16]

In October, Borthwick Cheney, having left her husband in the summer, met up with Wright in New York City.[17] From there, they sailed to Europe, and going to Berlin, so Wright could negotiate a portfolio of his work.[18] After that, Wright and Mamah Borthwick Cheney parted temporarily. She had settled in Leipzig, teaching English, and Wright settled in Italy to continue work on the portfolio. They joined each other there in February.[19] He moved his studio to a town within view of Florence, which is named Fiesole. While in Fiesole, Wright was particularly inspired by Michelozzo's Villa Medici because it was built into a hill, had commanding views of its surroundings, and featured gardens on two levels.[20] So, by February 1910, Wright made sketches of his future studio.

In 1910, the pair sought to return to the United States, but knew they could not escape scandal if they returned together to Oak Park.[21] Wright saw an alternative—his family's ancestral land near Spring Green, Wisconsin. Wright returned alone to the United States in October 1910, publicly reconciling with his wife, Catherine, while working to secure money to buy land on which to build a house for himself and Borthwick Cheney.[22] On April 3, 1911, Wright wrote to client, Darwin D. Martin, requesting money so that he could "see about building a small house" for his mother.[23]

On the 10th, Wright's mother Anna signed the deed for the property. By using Anna's name, Wright was able to secure the 31.5-acre (12.7 ha) property without attracting any attention to the affair.[24][25] Late in the summer, Mamah Borthwick (having divorced Cheney and legally reverting to her maiden name)[26] quietly moved into the property, staying with Wright's sister, Jane Porter, at her home, Tan-y-Deri. However, Wright and Borthwick's new property was discovered by a Chicago Examiner reporter that fall, and the affair made headlines in the Chicago Tribune on Christmas Eve. [27][28]

Taliesin I

At Taliesin, Wright wanted to live in unison with Mamah, his ancestry, and with nature. He chose only local building materials. The house was designed to nestle against the hill, in an example of Wright's "organic architecture". The bands of windows, one of his trademarks, allow nature to enter the house. The transitions from interior to exterior are fluent, which was radical at the time. "I attend the greatest of churches. I spell nature with a capital N. That is my church" (TV interview in 1957).[14]

The Taliesin house had three sections: a long section on the east, which held the residential wing (where Wright and Borthwick lived); a long section on the west, which held the agricultural wing; and a section connecting these two, the office wing. The office wing held the drafting studio and workroom, and an apartment for the head draftsman.[29] This apartment may have originally been intended for Wright's mother.[30] Typical of a Prairie School design, the house was, as Wright described, "low, wide, and snug."[31] As with most of his houses, Wright designed the furniture.[31] The one-story complex was accessed by a road leading up the hill to the rear of the building.[29] The estate gateway was on County Road C, just west of Wisconsin Road 23. Iron entry gates were flanked by limestone piers capped with planter urns.[32]

Wright chose yellow limestone for the house from a quarry of outcropping ledges on a nearby hill. Local farmers helped Wright move the stone up the Taliesin hill. Stones were laid in long, thin ledges, evoking the natural way that they were found in the quarry and across the Driftless Area.[33] Plaster for the interior walls was mixed with sienna, giving the finished product a golden hue.[34] This caused the plaster to resemble the sand on the banks of the nearby Wisconsin River.[35]

The outside plaster walls were similar, but mixed with cement, resulting in a grayer color. Windows were placed so that sun could come through openings in every room at every point of the day. Wright chose not to install gutters so that icicles would form in winter.[34] Shingles on the gradually-pitched roof were designed to weather to a silver-grey color, matching the branches of nearby trees.[36] A porte-cochère was built over the main entrance of the living quarters to provide shelter for visiting automobiles.[37] The finished house measured approximately 12,000 square feet (1,100 m2) of enclosed space.[38]

Life at Taliesin

Upon moving in with Borthwick in the winter 1911, Wright resumed work on his architectural projects, but he struggled to secure commissions because of the ongoing negative publicity over his affair with Borthwick (whose ex-husband, Edwin Cheney, maintained main custody of their son and daughter). However, Wright did produce some of his most acclaimed works during this time period, including the Midway Gardens in Chicago and the Avery Coonley Playhouse in Riverside. He also indulged his hobby for collecting Japanese art, and quickly became a renowned authority. Borthwick translated four works from Swedish difference feminist Ellen Key.[39]

Wright designed the gardens with the assistance of landscape architect, Jens Jensen. This included over a thousand fruit trees and bushes ordered by from in 1912. Wright requested two hundred and eighty-five apple trees planted, including one hundred McIntosh, fifty Wealthy, fifty Golden Russet, and fifty Fameuse. Among the bushes were three hundred gooseberry, two hundred blackberry, and two hundred raspberry. The property also grew pears, asparagus, rhubarb, and plums.[40] It is unknown exactly how many were planted, because part of the orchard was destroyed during a railroad strike.[41]

The fruit and vegetable plants were placed along the contour of the estate, which may have been done to mimic the farms he saw while in Italy.[42] Wright also dammed a creek on the property to create an artificial lake, which was stocked with fish and aquatic fowl. This water garden, probably inspired by the ones he saw in Japan, created a natural gateway to the property.[43]

In 1912, Wright designed what he called a "tea circle" in the middle of the courtyard, adjacent to the crown of the hill. This circle was heavily inspired by Jens Jensen's council circles, but also took influence from Japanese wabi-sabi landscape architecture. Unlike Jensen's circles, the rough-cut limestone tea circle was much larger and featured a pool in the center.[44] The circle featured a curved stone bench flanked with Chinese jars built during the Ming Dynasty. The tea circle had two oak trees: one on the inner edge of the seating areas, and one just outside of the stone seat. The remaining oak tree (outside of the stone seat) blew down in a storm in 1998.[45] The tea garden also included a large plaster replica of Flower in the Crannied Wall, a statue originally designed by Richard Bock for the Susan Lawrence Dana House, by Wright. The statue's namesake poem is inscribed on its rear.[46]

Attack and fire (1914)

Julian Carlton was a 31-year-old man who came to work as a chef and servant at Taliesin for the summer. Carlton was an Afro-Caribbean of West Indian descent, ostensibly from Barbados. He was recommended to Wright by John Vogelsong Jr., the caterer for the Midway Gardens project. Carlton and his wife Gertrude had previously served in the house of Vogelsong's parents in Chicago. Originally a genial presence on the estate, Carlton grew increasingly paranoid. He stayed up late at night with a butcher knife, looking out the window. This behavior had been noticed by Wright and Borthwick, who issued an ad in a local paper for a replacement cook. Carlton was given notice that August 15, 1914, would be his last day in their employ.[47]

Before he left, Carlton plotted to kill the residents of, and workers at, Taliesin. His primary target was draftsman Emil Brodelle, who had called Carlton a "black son-of-a-bitch" on August 12 for not following an order. Brodelle and Carlton also engaged in a minor physical confrontation two days later.[47] He planned the assault, targeting the noon hour, when Borthwick, her visiting children, and the studio personnel would be on opposite sides of Taliesin's living quarters awaiting lunch. Wright was away in Chicago completing Midway Gardens while Borthwick stayed at home with her two children, 11-year-old John and 8-year-old Martha. As only two survived that day and there was no criminal trial, the sequence of events have been posited based on details from the two survivors (William Weston and Herbert Fritz), and evidence found at the scene. On August 15, Carlton grabbed a shingling hatchet and began an attack. It is believed that he started with Borthwick and her children, John and Martha, who were waiting on the porch off the living room. Apparently, Mamah Borthwick was killed by a single blow to the head, and her son John was slaughtered as he sat in his chair. Martha managed to flee, but was hunted down and was found slain in the courtyard. He then coated the bodies in gasoline and set them on fire, setting the house ablaze.[48][49]

Carlton then turned his attention to the six other diners. It appears that he poured gasoline underneath the door of the far end of the living quarters and set the gasoline on fire. Draftsman Herbert Fritz managed to break open a window and escape,[50] though he broke his arm in the process. Carlton went around the outside of the room, near where Fritz had exited, and mortally wounded Brodelle. The next person coming out that side of the room, William Weston, was struck twice by Carlton and apparently left for dead. Carlton then attacked the others from the opposite side of the room: Brunker, Ernest Weston, and David Lindblom. Lindblom was attacked and burned, but still able to go for help with William Weston.

With the house empty and people wounded, Carlton ran to the basement and into a fireproof furnace chamber. He brought a small vial of hydrochloric acid with him as a fallback plan in case the heat became too much for him to handle. Carlton did attempt suicide by swallowing the acid, but it failed to kill him.[49][51][52]

Together, Lindblom and Weston ran to a neighboring farm to send the alert of the attack. Weston then returned to the Taliesin, and used a garden hose to help extinguish the flames. His efforts saved the studio (with the many of Wright's drawings and manuscripts), as well as the agricultural part of the building. Eventually, neighbors arrived to assist in putting out the fire, to tend to survivors, and search for the murderer. Gertrude was found in a nearby field, apparently unaware of her husband's intentions. She was dressed in travel clothes, expecting to catch a train to Chicago with Julian to seek a new job.[47]

Later in the afternoon, Sheriff John Williams located Carlton and arrested him. Carlton was transferred to the county jail in Dodgeville.[49]

Gertrude was released from police custody shortly after the incident. She was sent to Chicago with $7 and was never heard from again. The hydrochloric acid that Carlton ingested failed to kill him, but did badly burn his esophagus, which made it difficult for him to ingest food. Carlton was indicted on August 16 and was charged with the murder of Emil Brodelle, the only death that was directly witnessed by a survivor. Carlton entered a not guilty plea. Forty-seven days after the fire, before the case could be heard, Carlton died of starvation in his cell.[53][54]

Aftermath

Bodies of the dead and injured were brought to Tan-y-Deri, the nearby home of Wright's sister, Jane Porter. The dead were Mamah and Emil, with John missing (his remains were later found incinerated). Martha Cheney, foreman Thomas Brunker, and Ernest Weston (13-year-old son of William Weston) would die later that day or that night. Gardener David Lindblom survived until August 18 (Tuesday morning).

Wright returned to Taliesin that night with his son John, and Edwin Cheney.[49] Cheney brought the remains of his children back to Chicago while Wright buried Mamah Borthwick on the grounds of nearby Unity Chapel [55] (the chapel of the mother's side of his family). Heartbroken over the loss of his lover, Wright did not mark the grave because he could not bear to be reminded of the tragedy.[56] He also did not hold a funerary service for Borthwick, although he did fund and attend services for his employees.[57]

Wright struggled with the loss of Borthwick, experiencing symptoms of conversion disorder: insomnia, weight loss, and temporary blindness.[58] After a few months of recovery, aided by his sister Jane Porter, Wright moved to an apartment he rented in Chicago at 25 East Cedar Street.[59] The attack also had a profound effect on Wright's design principles; biographer Robert Twombly writes that his Prairie School period ended after the loss of Borthwick.[60]

Taliesin II

Within a few months of his recovery, Wright began work on rebuilding Taliesin, naming the rebuilt structure "Taliesin II":

There is release from anguish in action. Anguish would not leave Taliesin until action for renewal began. Again, and at once, all that had been in motion before at the will of the architect was set in motion. Steadily, again, stone by stone, board by board, Taliesin the II began to rise from Taliesin the first.[61][62]

The new complex was mostly identical to the original building. The dam (which burst less than a week after the murders) was rebuilt;[63] Wright added an observation platform, perhaps inspired by the one he designed in Baraboo.[64] Later, he built a hydroelectric generator in an unsuccessful effort to make Taliesin completely self-sufficient. The generator was built in the style of a Japanese temple. Within only a few years, parts of the structure eroded away. It was demolished in the 1940s.[65]

Around Christmas time of 1914 while designing the residence after the first devastating fire, Wright received a sympathetic letter from "Maude" Miriam Noel, who contacted him after reading about the Taliesin fire and murders. [66] Wright exchanged correspondence with the wealthy divorcee and met with her at his Chicago office. Wright was quickly infatuated, and the two began a relationship. By spring 1915, Taliesin II was completed and Noel moved there with Wright.

Wright's first wife Catherine finally granted him a divorce in 1922,[67] meaning that Wright could marry Noel a year later.[68] Although Wright admired Noel's erratic personality at first, her behavior (later identified as schizophrenia) led to a miserable life together at Taliesin.[69] Noel left Wright by the spring of 1924.[70]

In the new Taliesin, Wright worked to repair his tarnished reputation. He secured a commission to design the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, Japan; when the building was undamaged following the Great Kantō earthquake of 1923, Wright's reputation was restored. Although he later expanded the agricultural wing, Wright spent little time at the second Taliesin house, often living near his construction sites abroad.[71] Instead of serving as a full-time residence, Wright treated Taliesin like an art museum for his collection of Asian works.[72] Wright only truly lived at Taliesin II starting in 1922, after his work at the Imperial Hotel was completed.[73]

On April 20, 1925, Wright returned from eating dinner in the detached dining room when he noticed smoke billowing from his bedroom. By that time of night, most of the employees had returned home; only a driver and one apprentice were left in the complex. Unlike the first Taliesin fire, Wright was able to get help immediately. However, the fire quickly spread due to high winds. Despite the efforts of Wright and his neighbors to extinguish the flame, the living quarters of the second Taliesin were quickly destroyed. However, the workrooms where Wright kept his architectural drafts were spared.[74] According to Wright's autobiography, the fire appeared to have begun near a telephone in his bedroom.[58] Wright also mentioned a lightning storm approaching immediately before noticing the fire. Wright scholars speculate that the storm may have caused an electrical surge through the telephone system, sparking the fire.[75]

Taliesin III

Once again, the architect began rebuilding the living quarters of Taliesin. He also wrote about this in his 1932 autobiography, naming the house "Taliesin III":

Well—counselled [sic] by the living—there was I alive in their midst, key to a Taliesin nobler than the first if I could make it. And I had faith that I could build another Taliesin!

A few days later clearing away the debris to reconstruct I picked up partly calcined marble heads of the Tang-dynasty, fragments of the black basalt of the splendid Wei-stone, Sung soft-clay sculpture and gorgeous Ming pottery turned to the color of bronze by the intensity of the blaze. The sacrificial offerings to—whatever Gods may be.

And I put these fragments aside to weave them into the masonry—the fabric of Taliesin III that now—already in mind—was to stand in place of Taliesin II. And I went to work.[76]

Wright was deeply in debt following the destruction of Taliesin II. Aside from debts owed on the property, his divorce from Noel forced Wright to sell much of his farm machinery and livestock. Wright was also forced to sell his prized Japanese prints at half value to pay his debts. The Bank of Wisconsin foreclosed on Taliesin in 1927 and Wright was forced to move to La Jolla, California.

Shortly before the bank was to begin an auction on the property, Wright's former client Darwin Martin conceived a scheme to save the property. He formed a company called Frank Lloyd Wright Incorporated to issue stock on Wright's future earnings. Many of Wright's former clients and students purchased stock in Wright to raise $70,000. The company successfully bid on Taliesin for $40,000, returning it to Wright.[77]

Wright returned to Taliesin by October, 1928.[78] Wright's interaction with Taliesin lasted for the rest of his life, and eventually, he purchased the surrounding land, creating an estate of 593 acres (2.4 km²).[79]

Some of Wright's best-known buildings and most ambitious designs were created at his studio in the Taliesin III period. Works completed at Taliesin through the 1930s include Fallingwater (the house for Edgar Sr. and Liliane Kaufmann), the world headquarters for S.C. Johnson, and the first Usonian house for Herbert and Katherine Jacobs.

After World War II, Wright moved his studio work in Wisconsin to the drafting studio at the Hillside Home School. After that, Wright used the studio at Taliesin for meeting with prospective apprentices and clients.[80][81]

In its final form, the Taliesin III building measured 37,000 square feet (3,400 m2). All Wright buildings on the property combine for 75,000 square feet (7,000 m2), just short of 2 acres (0.81 ha), on 600 acres (240 ha) of land.[82]

Taliesin Fellowship

Wright inherited the nearby Hillside Home School when it became insolvent in 1915 (the school had been run by his aunts, and the building was designed by him). In 1928, Wright conceived the idea of hosting a school there and issued a proposal to the University of Wisconsin that would have created the Hillside Home School for the Allied Arts; however, the plan was later abandoned.[83] In 1932, the Wrights instead established the private Taliesin Fellowship, where fifty to sixty apprentices could come to Taliesin to study under the architect's mentorship. Apprentices helped him develop the estate at a time when Wright received few commissions for his work, including the Hillside Home School building, renovating the original school gymnasium into a theater. Apprentices under Wright's direction also constructed a drafting studio and dormitories. In 1937, Wright designed and the apprentices began construction on a winter home in Scottsdale, Arizona, which became known as Taliesin West. After this, Wright and the fellowship "migrated" between the two homes each year.[84] Notable fellows include Arthur Dyson, "Fay" Jones, Shao Fang Sheng, Paolo Soleri, Edgar Tafel, and Paul Tuttle.[85]

Wright did not consider the fellowship a formal school, instead viewing it as a benevolent educational institution. He also worked to ensure G.I. Bill eligibility for returning World War II veterans.[84] The town of Wyoming, Wisconsin, and Wright became embroiled in a legal dispute over his claim of tax exemption. A trial judge agreed with the town, stating that, since apprentices did much of Wright's work, it was not solely a benevolent institution. Wright fought the case to the Wisconsin Supreme Court. When Wright lost the case there in 1954,[86] he threatened to abandon the estate. However, he was persuaded to stay after some friends raised $800,000 to cover the back taxes at a benefit dinner.[84][87]

Preservation

In 1940, Frank Lloyd Wright, his third wife Olgivanna, and his son-in-law William Wesley Peters formed the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Upon Wright's death on April 9, 1959, ownership of the Taliesin estate in Spring Green, as well as Taliesin West, passed into the hands of the foundation. The Taliesin Fellowship continued to use the Hillside School as The School of Architecture at Taliesin. The fellowship allowed tours of the school, but initially did not permit visitation of the house or other grounds.[88]

When the group spent two summers in Switzerland, rumors started that they were planning on selling the house to S. C. Johnson, a former Wright client. Instead, the fellowship sold a surrounding piece of land to a developer associated with the company, intending to develop a tourist complex.[88] The 3,000-acre (1,200 ha) resort included an eighteen-hole golf course, restaurant, and a visitor's center.[89]

Recognition

In 1973, Taliesin and the surrounding estate was listed in the National Register of Historic Places[90] and on January 7, 1976, it was recognized as a National Historic Landmark (NHL) District by the National Park Service. A National Historic Landmark is a site deemed to have "exceptional value to the nation."[91] The properties contributing to the district are the landscape, Taliesin III, the pool and gardens in the courtyard, Hillside Home School (which includes the Hillside drafting studio and the theater), the dam, Romeo and Juliet Windmill, Midway Barn, and Tan-Y-Deri.

In the late 1980s, Taliesin and Taliesin West were together nominated as a World Heritage Site, a UNESCO designation for properties with special worldwide significance. The nomination was rejected because the organization wanted to see a larger nomination with more Wright properties.[92] In 2008, the National Park Service submitted the Taliesin estate along with nine other Frank Lloyd Wright properties to a tentative list for World Heritage Status, which the National Park Service says is "a necessary first step in the process of nominating a site to the World Heritage List."[93][94] After revised proposals,[95] Taliesin and seven other properties were inscribed on the World Heritage List under the title "The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright" in July 2019.[96]

In 1987, the National Park Service evaluated the 1,811 NHLs nationwide for historical integrity and threat of damage. Taliesin was declared a "Priority 1" NHL, a site that is "seriously damaged or imminently with such damage."[97][98] Furthermore, the site was listed by the National Trust for Historic Preservation as one of America's Most Endangered Places in 1994, citing its "water damage, erosion, foundation settlement and wood decay."[99] Taliesin Preservation, Inc. (TPI), a non-profit organization, was established in 1991 to restore Taliesin.[100]

Rehabilitation

On June 18, 1998, a severe storm damaged the estate. The large oak tree at the center of the tea circle in the courtyard fell down on top of the house.[101] Ten days after this, heavy rains caused a mudslide north of the building.[102] The next year, another storm collapsed a tunnel underneath the studio wing.[103] A 1999 grant from Save America's Treasures helped defray costs to re-roof Taliesin III, to stabilize its foundation, and to connect it to a local sewage treatment plant.[104][105]

Over $11 million has been spent on the rehabilitation of Taliesin since 1998. Unfortunately, its preservation is "fraught with epic difficulties", because Wright never thought of it as a series of buildings with a long-term future. It was built by inexperienced students, without solid foundations.[106] Financing renovations has been challenging because revenue from Taliesin visitation has been lower than projected.[107]

TPI provides tours from May 1 through October 31. Other visitation opportunities are available the rest of the year, but these are variable and visitors are encouraged to visit the organization's website.[108] Roughly 25,000 people visit Taliesin each year.[1]

Assessment

Architectural historian James F. O'Gorman compares Taliesin to Thomas Jefferson's Monticello, calling it "not a mere building but an entire environment in which man, architecture and nature form a harmonious whole." He continues that the building is an expression of Romanticism influence in architecture.[109] William Barillas, in an essay of the Prairie School movement, agrees with O'Gorman's assessment and calls Taliesin "the ultimate prairie house."[109] In "House Proud", an article in Boston Globe Magazine, Pulitzer Prize winning architecture critic Robert Campbell wrote that Taliesin is “my candidate for the title of the greatest single building in America.”[110]

In Taliesin 1911–1914, a collection of essays about the first house, the authors and editor conclude that Taliesin was "Wright's architectural self-portrait."[111] In a 2009 publication for the Thoreau Society, Naomi Uechi notes thematic similarities between the architecture of Taliesin and the concept of simplicity advocated by philosopher Henry David Thoreau.[112] Architectural historian Neil Levine highlighted the abstract nature of the complex, comparing it to the works of Pablo Picasso.[113]

See also

- List of Frank Lloyd Wright works

- Taliesin West

References

- Verburg, Steven (July 25, 2010). "Amid an Architectural Wonder, a Family Grows". Wisconsin State Journal. Archived from the original on August 29, 2016. Retrieved October 17, 2013.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- "Driftless Area National Wildlife Refuge". United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- Mickelson & Attig 1999, p. 93.

- Henning 2011, p. 3.

- Tauscher, Cathy; Hughes, Peter (2007). "Jenkin Lloyd Jones". Dictionary of Unitarian Universalist Biography. Unitarian Universalist History and Heritage Society. Archived from the original on October 10, 2014. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- McCrea 2012, p. 35.

- McCrea 2012, p. 56.

- "Taliesin: A Masque". d.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/. 2022. Archived from the original on 2021-11-18. Retrieved 2022-05-16.

- Menocal 1992, pp. 44–45.

- Wright 1943, p. 167.

- Wright 1943, p. 170.

- McCrea 2012, p. 114.

- "Dokumentarfilm: Frank Lloyd Wright - Der Phoenix aus der Asche". www.ardmediathek.de (in German). 2021. Archived from the original on 2021-10-08. Retrieved 2021-10-08.

- Henning 2011, p. 5.

- McCrea 2012, p. 16.

- Secrest 1992, p. 203.

- Alofsin 1994, p. 30.

- McCrea 2012, p. 17.

- McCrea 2012, p. 27.

- McCrea 2012, pp. 17–19.

- Secrest 1992, p. 207-08.

- Secrest 1992, p. 209.

- McCrea 2012, p. 25.

- Henning 2011, p. 4.

- Secrest 1992, p. 207.

- McCrea 2012, p. 57.

- Secrest 1992, p. 212.

- McCrea 2012, p. 175.

- Henning 2011, p. 24.

- Wright 1943, p. 174.

- Henning 2011, p. 10.

- Wright 1943, pp. 170–171.

- Wright 1943, p. 173.

- Henning 2011, p. 17.

- Henning 2011, p. 16.

- Henning 2011, p. 14.

- Henning 2011, p. 6.

- McCrea 2012, p. 131.

- McCrea 2012, p. 176.

- McCrea 2012, p. 176-177.

- McCrea 2012, p. 177.

- McCrea 2012, p. 178.

- McCrea 2012, p. 179.

- Henning 2011, p. 34.

- Henning 2011, p. 40.

- McCrea 2012, p. 192.

- Secrest 1992, pp. 218–219.

- McCrea 2012, pp. 188–191.

- Mara Bovsun (January 25, 2014). "Cook massacres seven at Wisconsin home Frank Lloyd Wright built for his mistress". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on December 6, 2017. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

- "The Massacre at Frank Lloyd Wright's "Love Cottage"". HISTORY.com. Archived from the original on 2017-12-06. Retrieved 2017-12-06.

- "Frank Lloyd Wright | Ken Burns | PBS | Watch Frank Lloyd Wright | Ken Burns Documentary | PBS". PBS. Archived from the original on 2019-09-03.

- McCrea 2012, pp. 195–196.

- Klein, Christopher. "The Massacre at Frank Lloyd Wright's "Love Cottage"". HISTORY. Archived from the original on 4 February 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- Weekly Home News & August 20, 1914.

- McCrea 2012, p. 193.

- McCrea 2012, p. 194.

- Wright 1943, p. 262.

- McCrea 2012, p. 198.

- Drennan 2007, p. 157.

- Frank Lloyd Wright. An Autobiography, in Frank Lloyd Wright Collected Writings: 1930-32, volume 2. Edited by Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, introduction by Kenneth Frampton (1992; Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., New York City, 1992), 241.

- Drennan 2007, p. 160.

- Secrest 1992, p. 222.

- Henning 2011, p. 68.

- Henning 2011, pp. 70–72.

- Finis Farr. Frank Lloyd Wright: A Biography. (1961; Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, 147).

- Secrest 1992, p. 271.

- Secrest 1992, p. 279.

- Huxtable 2004, p. 142.

- Secrest 1992, p. 280.

- Smith 1997, p. 50.

- Smith 1997, p. 138.

- Packard, Korab & Hunt 1980, p. 698.

- Wright 1943, pp. 261–262.

- Smith 1992, p. 315.

- Frank Lloyd Wright. An Autobiography. Frank Lloyd Wright Collected Writings: 1930-32, volume 2. Edited by Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, introduction by Kenneth Frampton (Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., New York City, 1992), 295.

- Secrest 1992, p. 333-335.

- Secrest 1992, p. 342.

- Hoppen 1997, pp. 59–60.

- "Frank Lloyd Wright and Man in Studio | Photograph". Wisconsin Historical Society. December 1, 2003. Archived from the original on October 4, 2021. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- "Art Work at Taliesin | Photograph". Wisconsin Historical Society. December 1, 2003. Archived from the original on October 4, 2021. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- "Frank Lloyd Wright FAQs". Taliesin Preservation, Inc. Archived from the original on October 17, 2013. Retrieved October 17, 2013.

- Gottlieb 2001, p. 9.

- Matheson, Helen (April 10, 1959). "Wright: A Force of Nature". Wisconsin State Journal. p. 6. Archived from the original on November 9, 2021. Retrieved August 6, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- Piu, Lara (May 3, 2017). "150 Years After Frank Lloyd Wright's Birth, Taliesin West Is Still Evolving — Here's How". Archived from the original on October 22, 2018. Retrieved October 22, 2018.

- Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation v. Wyoming, 267 Wis. 599 (Wis. 1954) ("Since Mr. Wright and his family are direct beneficiaries and the benefit to the public purely incidental, necessarily plaintiff's effort to be relieved of taxes on its property must fail because of the legal principles controlling tax exemptions").

- "Wright's Taliesin Is Still Active". The Evening Standard. Uniontown, PA. Associated Press. June 29, 1965. p. 3. Archived from the original on November 9, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- Van Goethem, Larry (July 15, 1967). "Taliesin East--a Living Symbol of Frank Lloyd Wright's Philosophy". Janesville Daily Gazette. Janesville, WI. p. 1. Archived from the original on November 9, 2021. Retrieved August 14, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Spring Green Recreational Plan Unveiled". The Daily Telegram. Eau Claire, WI. United Press International. July 18, 1966. p. 11. Archived from the original on November 9, 2021. Retrieved August 14, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- Carolyn Pitts (July 29, 1975). "Taliesin– Nomination Form". National Register of Historic Places. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- Code of Federal Regulations: Parks, Forests, and Public Property (PDF), United States Government Printing Office, p. 301, archived (PDF) from the original on October 18, 2013, retrieved October 17, 2013

- Allsopp, Phil (Fall 2008). "Preservation, Maintenance Key Funding Priorities for Capital Campaign". Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly. 19 (4).

- "New US World Heritage Tentative List". National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2012-10-26. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- "Tentative List: Frank Lloyd Wright Buildings". UNESCO. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013. Retrieved October 17, 2013.

- "Eight Buildings Designed by Frank Lloyd Wright Nominated to the UNESCO World Heritage List". Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. December 20, 2018. Archived from the original on June 25, 2019. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

- "The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on July 9, 2019. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

- Damaged and Threatened National Historic Landmarks, 1987, National Park Service, 1987, retrieved October 18, 2013

- "Preservation". Taliesin Preservation, Inc. Archived from the original on October 18, 2013. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- "11 Most Endangered Historic Places: Frank Lloyd Wright's Taliesin". Archived from the original on October 19, 2013. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- "Frank Lloyd Wright's Taliesin - Wisconsin Attraction". Frank Lloyd Wright's Taliesin. Archived from the original on 2020-09-04. Retrieved 2020-08-29.

- https://archive.org/details/npr-all-things-considered-06-21-1998 Discussion about the tree fall is on "All Things Considered" from National Public Radio. The segment begins at 36:33.

- Wisconsin State Journal, August 14, 1998. "[A] mudslide 10 days after the tree fell could be a harbinger of more serious problems. The mudslide occurred when 4 inches of rain fell in an hour and affected a 10-yard by 30-yard section of the hill."

- Gould, Whitney (October 15, 1999). "Rebuilding the Wright House". The Salina Journal. Salina, KS. Archived from the original on November 9, 2021. Retrieved August 6, 2014 – via Wisconsin State Journal, Newspapers.com.

- "Preservation Projects: Completed Projects". Taliesin Preservation, Inc. Archived from the original on April 14, 2012. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- "Search the Database of Funded Projects". National Park Service. Archived from the original on October 19, 2013. Retrieved October 18, 2013. User must select "Taliesin" from the "Title" dropdown list.

- Martell, Chris (December 8, 2008). "Taliesin Restoration Fraught with Epic Difficulties". Wisconsin State Journal. Archived from the original on December 10, 2008. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- "Restoring Wright: The Difficult Task of Preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's Taliesin". The Economist. May 3, 2011. Archived from the original on August 14, 2014. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- "Frank Lloyd Wright's Taliesin - Wisconsin Attraction". Archived from the original on 2020-09-04. Retrieved 2020-08-29.

- Barillas 2006, pp. 48–49.

- Boston Globe Magazine, December 13, 1992.

- Menocal 1992, p. ix.

- Uechi, Naomi (2009). Walls, Laura Dassow (ed.). "Evolving Transcendentalism: Thoreauvian Simplicity in Frank Lloyd Wright's Taliesin and Contemporary Ecological Architecture". The Concord Saunterer. Concord, MA. 17: 73–98. JSTOR 23395074.

- Levine, Neil (Spring 1986). "Abstraction and Representation in Modern Architecture: The International Style and Frank Lloyd Wright". AA Files (11): 3–21. JSTOR 29543489.

Bibliography

- Alofsin, Anthony (1993). Frank Lloyd Wright--the Lost Years, 1910-1922: A Study of Influence. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-9820-6301-9.

- Barillas, William (2006). The Midwestern Pastoral: Place and Landscape in Literature of the American Heartland. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-8214-1660-0.

- Drennan, William (2007). Death in a Prairie House: Frank Lloyd Wright and the Taliesin Murders. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-22210-9.

- Gottlieb, Lois Davidson (2001). A Way of Life: An Apprenticeship with Frank Lloyd Wright. Mulgrave, Victoria, Australia: The Images Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-86470-096-1.

- Henning, Randolph C. (2011). Frank Lloyd Wright's Taliesin. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-28284-4.

- Hoppen, Donald W. (1997). The Seven Ages of Frank Lloyd Wright. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-29420-9.

- Huxtable, Ada (2004). Frank Lloyd Wright: A Life. New York City, NY: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-1-4406-3173-3.

- McCrea, Ron (2012). Building Taliesin: Frank Lloyd Wright's Home of Love and Loss. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0-87020-606-1.

- Menocal, Narciso (1992). Wright Studies, Volume One: Taliesin 1911–1914. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0-8093-1625-0.

- Mickelson, David M.; Attig, John W., eds. (1999). Glacial Processes: Past and Present. Boulder, CO: Geological Society of America.

- Packard, Robert T.; Korab, Balthazar; Hunt, William Dudley (1980). Encyclopedia of American Architecture. New York City, NY: McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-048010-0.

- Secrest, Meryle (1992). Frank Lloyd Wright: A Biography. New York City, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. ISBN 978-0-226-74414-8.

- Smith, Kathryn (1997). Frank Lloyd Wright's Taliesin and Taliesin West. New York City, NY: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-3991-2.

- Storrer, William Allin (2006). The Frank Lloyd Wright Companion. Chicago, IL: University Of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-77621-2.. Taliesin I S.172. Taliesin II S.180. Taliesin III S.218.

- Wright, Frank Lloyd (1943). Frank Lloyd Wright: An Autobiography. New York City, NY: Duell, Sloan and Pearce. ISBN 978-0-7649-3243-4.

External links

- The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation

- The School of Architecture at Taliesin

- Taliesin Preservation

- 360° Virtual Tour at Tour de Force 360VR

- Taylor Woolley's photographs of Taliesin I at the Utah Historical Society

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. WI-339, "Taliesin, 5841 County Highway C, Spring Green, Sauk County, WI", 1 color transparency, 1 photo caption page