The Ashes

The Ashes is a Test cricket series played between England and Australia. The term originated in a satirical obituary published in a British newspaper, The Sporting Times, immediately after Australia's 1882 victory at The Oval, its first Test win on English soil. The obituary stated that English cricket had died, and "the body will be cremated and the ashes taken to Australia".[1] The mythical ashes immediately became associated with the 1882–83 series played in Australia, before which the English captain Ivo Bligh had vowed to "regain those ashes". The English media therefore dubbed the tour the quest to regain the Ashes.

The Ashes urn, made of terracotta and about 10.5

cm (4") tall, is reputed to contain the ashes of a burnt cricket bail. | |

| Countries | |

|---|---|

| Administrator | International Cricket Council |

| Format | Test cricket |

| First edition | 1882–83 (Australia) |

| Latest edition | 2021–22 (Australia) |

| Next edition | 2023 (England) |

| Tournament format | 5-match series |

| Number of teams | 2 |

| Current trophy holder | |

| Most successful | |

| Most runs | |

| Most wickets | |

After England had won two of the three Tests on the tour, a small urn was presented to Bligh by a group of Melbourne women including Florence Morphy, whom Bligh married within a year.[2] The contents of the urn are reputed to be the ashes of a wooden bail, and were humorously described as "the ashes of Australian cricket".[3] It is not clear whether that "tiny silver urn" is the same as the small terracotta urn given to the MCC by Bligh's widow after his death in 1927.

The urn has never been the official trophy of the Ashes series, having been a personal gift to Bligh.[4] However, replicas of the urn are often held aloft by victorious teams as a symbol of their victory in an Ashes series. Since the 1998–99 Ashes series, a Waterford Crystal representation of the Ashes urn (called the Ashes Trophy) has been presented to the winners of an Ashes series as the official trophy of that series. Irrespective of which side holds the tournament, the original urn remains in the MCC Museum at Lord's; it has, however, been taken to Australia to be put on touring display on two occasions: as part of the Australian Bicentenary celebrations in 1988 and to accompany the Ashes series in 2006–07.

An Ashes series traditionally consists of five Tests, hosted in turn by England and Australia at least once every two years. The Ashes are regarded as being held by the team that most recently won the series. If the series is drawn, the team that currently holds the Ashes retains the trophy.

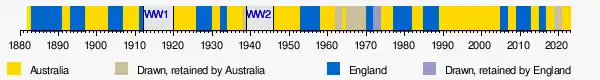

There have been 72 Ashes series: Australia have won 34, England have won 32 and six series have been drawn.

1882 origins

The first Test match between England and Australia was played in Melbourne, Australia, in 1877, though the Ashes legend started later, after the ninth Test, played in 1882. On their tour of England that year the Australians played just one Test, at the Oval in London. It was a low-scoring affair on a difficult wicket.[5] Australia made a mere 63 runs in their first innings, and England, led by A. N. Hornby, took a 38-run lead with a total of 101. In their second innings, Australia, boosted by a spectacular 55 runs off 60 deliveries from Hugh Massie, managed 122, which left England only 85 runs to win. The Australians were greatly demoralised by the manner of their second-innings collapse, but fast bowler Fred Spofforth, spurred on by the gamesmanship of his opponents, in particular W. G. Grace, refused to give in. "This thing can be done," he declared. Spofforth went on to devastate the English batting, taking his final four wickets for only two runs to leave England just eight runs short of victory.

When Ted Peate, England's last batsman, came to the crease, his side needed just ten runs to win, but Peate managed only two before he was bowled by Harry Boyle. An astonished Oval crowd fell silent, struggling to believe that England could possibly have lost on home soil. When it finally sank in, the crowd swarmed onto the field, cheering loudly and chairing Boyle and Spofforth to the pavilion.

When Peate returned to the pavilion he was reprimanded by his captain for not allowing his partner, Charles Studd (one of the best batsmen in England, having already hit two centuries that season against the colonists), to get the runs. Peate humorously replied, "I had no confidence in Mr Studd, sir, so thought I had better do my best."[6]

The momentous defeat was widely recorded in the British press, which praised the Australians for their plentiful "pluck" and berated the Englishmen for their lack thereof. A celebrated poem appeared in Punch on Saturday, 9 September. The first verse, quoted most frequently, reads:

Well done, Cornstalks! Whipt us

Fair and square,

Was it luck that tript us?

Was it scare?

Kangaroo Land's 'Demon', or our own

Want of 'devil', coolness, nerve, backbone?

On 31 August, in the Charles Alcock-edited magazine Cricket: A Weekly Record of The Game, there appeared a mock obituary:

SACRED TO THE MEMORY

OF

ENGLAND'S SUPREMACY IN THE

CRICKET-FIELD

WHICH EXPIRED

ON THE 29TH DAY OF AUGUST, AT THE OVAL

"ITS END WAS PEATE"

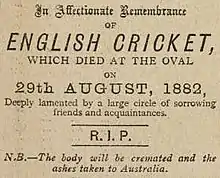

On 2 September a more celebrated mock obituary, written by Reginald Shirley Brooks, appeared in The Sporting Times. It read:

In Affectionate Remembrance

of

ENGLISH CRICKET,

which died at the Oval

on

29 August 1882,

Deeply lamented by a large circle of sorrowing

friends and acquaintances

R.I.P.

N.B.—The body will be cremated and the

ashes taken to Australia.

Ivo Bligh promised that on 1882–83 tour of Australia, he would, as England's captain, "recover those Ashes". He spoke of them several times over the course of the tour, and the Australian media quickly caught on. The three-match series resulted in a two-one win to England, notwithstanding a fourth match, won by the Australians, whose status remains a matter of ardent dispute.[7][8]

In the 20 years following Bligh's campaign the term "the Ashes" largely disappeared from public use. There is no indication that this was the accepted name for the series, at least not in England. The term became popular again in Australia first, when George Giffen, in his memoirs (With Bat and Ball, 1899), used the term as if it were well known.[9]

The true and global revitalisation of interest in the concept dates from 1903, when Pelham Warner took a team to Australia with the promise that he would regain "the ashes". As had been the case on Bligh's tour 20 years before, the Australian media latched fervently onto the term and, this time, it stuck. Having fulfilled his promise, Warner published a book entitled How We Recovered the Ashes. Although the origins of the term are not referred to in the text, the title served (along with the general hype created in Australia) to revive public interest in the legend. The first mention of "the Ashes" in Wisden Cricketers' Almanack occurs in 1905, while Wisden's first account of the legend is in the 1922 edition.

Urn

It took many years before the contests between England and Australia were consistently called "The Ashes", and so there was no concept of either a trophy or a physical representation of the ashes. As late as 1925, the following verse appeared in The Cricketers Annual:

So here's to Chapman, Hendren and Hobbs,

Gilligan, Woolley and Hearne

May they bring back to the Motherland,

The ashes which have no urn!

Nevertheless, several attempts had been made to embody the Ashes in a physical memorial. Examples include one presented to Warner in 1904, another to Australian captain M. A. Noble in 1909, and another to Australian captain W. M. Woodfull in 1934.

The oldest, and the one to enjoy enduring fame, was the one presented to Bligh, later Lord Darnley, during the 1882–83 tour. The precise nature of the origin of this urn is matter of dispute. Based on a statement by Darnley in 1894, it was believed that a group of Victorian ladies, including Darnley's later wife Florence Morphy, made the presentation after the victory in the Third Test in 1883. More recent researchers, in particular Ronald Willis[10] and Joy Munns[11] have studied the tour in detail and concluded that the presentation was made after a private cricket match played over Christmas 1882 when the English team were guests of Sir William Clarke, at his property "Rupertswood", in Sunbury, Victoria. This was before the matches had started. The prime evidence for this theory was provided by a descendant of Clarke.

In August 1926 Ivo Bligh (now Lord Darnley) displayed the Ashes urn at the Morning Post Decorative Art Exhibition held in the Central Hall, Westminster. He made the following statement about how he was given the urn:[12]

When in the autumn the English Eleven went to Australia it was said that they had come to Australia to "fetch" the ashes. England won two out of the three matches played against Murdoch's Australian Eleven, and after the third match some Melbourne ladies put some ashes into a small urn and gave them to me as captain of the English Eleven.

A more detailed account of how the Ashes were given to Ivo Bligh was outlined by his wife, the Countess of Darnley, in 1930 during a speech at a cricket luncheon. Her speech was reported by the Times as follows:[13]

In 1882, she said, it was first spoken of when the Sporting Times, after the Australians had thoroughly beaten the English at the Oval, wrote an obituary in affectionate memory of English cricket "whose demise was deeply lamented and the body would be cremated and taken to Australia". Her husband, then Ivo Bligh, took a team to Australia in the following year. Punch had a poem containing the words "When Ivo comes back with the urn" and when Ivo Bligh wiped out the defeat Lady Clarke, wife of Sir W. J. Clarke, who entertained the English so lavishly, found a little wooden urn, burnt a bail, put the ashes in the urn, and wrapping it in a red velvet bag, put it into her husband's (Ivo Bligh's) hands. He had always regarded it as a great treasure.

There is another statement which is not totally clear made by Lord Darnley in 1921 about the timing of the presentation of the urn. He was interviewed in his home at Cobham Hall by Montague Grover and the report of this interview was as follows:[14]

This urn was presented to Lord Darnley by some ladies of Melbourne after the final defeat of his team, and before he returned with the members to England.

He made a similar statement in 1926. The report of this statement in the Brisbane Courier was as follows:[15]

The proudest possession of Lord Darnley is an earthenware urn containing the ashes which were presented to him by Melbourne residents when he captained the Englishmen in 1882. Though the team did not win, the urn containing the ashes was sent to him just before leaving Melbourne.

The contents of the urn are also problematic; they were variously reported to be the remains of a stump, bail or the outer casing of a ball, but in 1998 Darnley's 82-year-old daughter-in-law said they were the remains of her mother-in-law's veil, casting a further layer of doubt on the matter. However, during the tour of Australia in 2006/7, the MCC official accompanying the urn said the veil legend had been discounted, and it was now "95% certain" that the urn contains the ashes of a cricket bail. Speaking on Channel Nine TV on 25 November 2006, he said x-rays of the urn had shown the pedestal and handles were cracked, and repair work had to be carried out. The urn is made of terracotta and is about 6 inches (150 mm) tall and may originally have been a perfume jar.

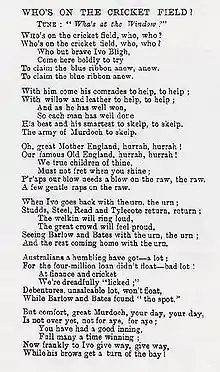

A label containing a six-line verse is pasted on the urn. This is the fourth verse of a song-lyric published in the Melbourne Punch on 1 February 1883:

When Ivo goes back with the urn, the urn;

Studds, Steel, Read and Tylecote return, return;

The welkin will ring loud,

The great crowd will feel proud,

Seeing Barlow and Bates with the urn, the urn;

And the rest coming home with the urn.

In February 1883, just before the disputed Fourth Test, a velvet bag made by Mrs Ann Fletcher, the daughter of Joseph Hines Clarke and Marion Wright, both of Dublin, was given to Bligh to contain the urn. During Darnley's lifetime there was little public knowledge of the urn, and no record of a published photograph exists before 1921. The Illustrated London News published this photo in January 1921 (shown above). When Darnley died in 1927 his widow presented the urn to the Marylebone Cricket Club and that was the key event in establishing the urn as the physical embodiment of the legendary ashes. MCC first displayed the urn in the Long Room at Lord's and since 1953 in the MCC Cricket Museum at the ground. MCC's wish for it to be seen by as wide a range of cricket enthusiasts as possible has led to its being mistaken for an official trophy. It is in fact a private memento, and for this reason it is never awarded to either England or Australia, but is kept permanently in the MCC Cricket Museum where it can be seen together with the specially made red and gold velvet bag and the scorecard of the 1882 match.

Because the urn itself is so delicate, it has been allowed to travel to Australia only twice. The first occasion was in 1988 for a museum tour as part of the Australian Bicentenary celebrations; the second was for the 2006/7 Ashes series.[16] The urn arrived on 17 October 2006, going on display at the Museum of Sydney. It then toured to other states, with the final appearance at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery on 21 January 2007.

In the 1990s, given Australia's long dominance of the Ashes and the popular acceptance of the Darnley urn as "the Ashes", the idea was mooted that the victorious team should be awarded the urn as a trophy and allowed to retain it until the next series. As its condition is fragile and it is a prized exhibit at the MCC Cricket Museum, the MCC would not agree. Furthermore, in 2002, Bligh's great-great-grandson Lord Clifton, the heir-apparent to the Earldom of Darnley, argued that the Ashes urn should not be returned to Australia because it belonged to his family and was given to the MCC only for safe keeping.

As a compromise, the MCC commissioned a larger replica of the urn in Waterford Crystal, known as the Ashes Trophy, to award to the winning team of each series starting with the 1998–99 Ashes.[17] This did little to diminish the status of the Darnley urn as the most important icon in cricket, the symbol of this old and keenly fought contest.

Series and matches

Quest to "recover those ashes"

Later in 1882, following the famous Australian victory at The Oval, Bligh led an England team to Australia, as he said, to "recover those ashes". Publicity surrounding the series was intense, and it was at some time during this series that the Ashes urn was crafted. Australia won the First Test by nine wickets, but in the next two England were victorious. At the end of the Third Test, England were generally considered to have "won back the Ashes" 2–1. A fourth match was played, against a "United Australian XI", which was arguably stronger than the Australian sides that had competed in the previous three matches; this game, however, is not generally considered part of the 1882–83 series. It is counted as a Test, but as a standalone. This match ended in a victory for Australia.

1884 to 1896

After Bligh's victory, there was an extended period of English dominance. The tours generally had fewer Tests in the 1880s and 1890s than people have grown accustomed to in more recent years, the first five-Test series taking place only in 1894–95. England lost only four Ashes Tests in the 1880s out of 23 played, and they won all the seven series contested.

There was more chopping and changing in the teams, given that there was no official board of selectors for each country (in 1887–88, two separate English teams were on tour in Australia) and popularity with the fans varied. The 1890s games were more closely fought, Australia taking its first series win since 1882 with a 2–1 victory in 1891–92. But England dominated, winning the next three series to 1896 despite continuing player disputes.

The 1894–95 series began in sensational fashion when England won the First Test at Sydney by just 10 runs having followed on. Australia had scored a massive 586 (Syd Gregory 201, George Giffen 161) and then dismissed England for 325. But England responded with 437 and then dramatically dismissed Australia for 166 with Bobby Peel taking 6 for 67. At the close of the second last day's play, Australia were 113–2, needing only 64 more runs. But heavy rain fell overnight and next morning the two slow left-arm bowlers, Peel and Johnny Briggs, were all but unplayable. England went on to win the series 3–2 after it had been all square before the Final Test, which England won by 6 wickets. The English heroes were Peel, with 27 wickets in the series at an average of 26.70, and Tom Richardson, with 32 at 26.53.

In 1896, England under the captaincy of W. G. Grace won the series 2–1, and this marked the end of England's longest period of Ashes dominance.

1897 to 1902

Australia resoundingly won the 1897–98 series by 4–1 under the captaincy of Harry Trott. His successor Joe Darling won the next three series in 1899, 1901–02, and the classic 1902 series, which became one of the most famous in the history of Test cricket.

Five matches were played in 1902 but the first two were drawn after being hit by bad weather. In the First Test (the first played at Edgbaston), after scoring 376 England bowled out Australia for 36 (Wilfred Rhodes 7/17) and reduced them to 46–2 when they followed on. Australia won the Third and Fourth Tests at Bramall Lane and Old Trafford respectively. At Old Trafford, Australia won by just 3 runs after Victor Trumper had scored 104 on a "bad wicket", reaching his hundred before lunch on the first day. England won the last Test at The Oval by one wicket. Chasing 263 to win, they slumped to 48–5 before Gilbert Jessop's 104 gave them a chance. He reached his hundred in just 75 minutes. The last-wicket pair of George Hirst and Rhodes were required to score 15 runs for victory. When Rhodes joined him, Hirst reportedly said: "We'll get them in singles, Wilfred." In fact, they scored thirteen singles and a two.[18]

The period of Darling's captaincy saw the emergence of outstanding Australian players such as Trumper, Warwick Armstrong, James Kelly, Monty Noble, Clem Hill, Hugh Trumble and Ernie Jones.

Reviving the legend

After what the MCC saw as the problems of the earlier professional and amateur series they decided to take control of organising tours themselves, and this led to the first MCC tour of Australia in 1903–04. England won it against the odds, and Plum Warner, the England captain, wrote up his version of the tour in his book How We Recovered The Ashes.[19] The title of this book revived the Ashes legend and it was after this that England v Australia series were customarily referred to as "The Ashes".

1905 to 1912

England and Australia were evenly matched until the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. Five more series took place between 1905 and 1912. In 1905, England's captain Stanley Jackson not only won the series 2–0, but also won the toss in all five matches and headed both the batting and the bowling averages. Monty Noble led Australia to victory in both 1907–08 and 1909. Then England won in 1911–12 by four matches to one. Jack Hobbs establishing himself as England's first-choice opening batsman with three centuries, while Frank Foster (32 wickets at 21.62) and Sydney Barnes (34 wickets at 22.88) formed a formidable bowling partnership.

England retained the Ashes when it won the 1912 Triangular Tournament, which also featured South Africa. The Australian touring party had been severely weakened by a dispute between the board and players that caused Clem Hill, Victor Trumper, Warwick Armstrong, Tibby Cotter, Sammy Carter and Vernon Ransford to be omitted.[20]

1920 to 1933

After the war, Australia took firm control of both the Ashes and world cricket. For the first time, the tactic of using two express bowlers in tandem paid off as Jack Gregory and Ted McDonald crippled the English batting on a regular basis. Australia recorded overwhelming victories both in England and on home soil. It won the first eight matches in succession including a 5–0 whitewash in 1920–1921 at the hands of Warwick Armstrong's team.

The ruthless and belligerent Armstrong led his team back to England in 1921 where his men lost only two games late in the tour to narrowly miss out of being the first team to complete a tour of England without defeat.

England won only one Test out of 15 from the end of the war until 1925.[21][22]

In a rain-hit series in 1926, England managed to eke out a 1–0 victory with a win in the final Test at The Oval. Because the series was at stake, the match was to be "timeless", i.e., played to a finish. Australia had a narrow first innings lead of 22. Jack Hobbs and Herbert Sutcliffe took the score to 49–0 at the end of the second day, a lead of 27. Heavy rain fell overnight, and next day the pitch soon developed into a traditional sticky wicket. England seemed doomed to be bowled out cheaply and to lose the match. In spite of the very difficult batting conditions, however, Hobbs and Sutcliffe took their partnership to 172 before Hobbs was out for exactly 100. Sutcliffe went on to make 161 and England won the game comfortably.[23] Australian captain Herbie Collins was stripped of all captaincy positions down to club level, and some accused him of throwing the match.

Australia's ageing post-war team broke up after 1926, with Collins, Charlie Macartney and Warren Bardsley all departing, and Gregory breaking down at the start of the 1928–29 series.

Despite the debut of Donald Bradman, the inexperienced Australians, led by Jack Ryder, were heavily defeated, losing 4–1.[24] England had a very strong batting side, with Wally Hammond contributing 905 runs at an average of 113.12, and Hobbs, Sutcliffe and Patsy Hendren all scoring heavily; the bowling was more than adequate, without being outstanding.

In 1930, Bill Woodfull led an extremely inexperienced team to England.

Bradman fulfilled his promise in the 1930 series when he scored 974 runs at 139.14, which remains a world record Test series aggregate. A modest Bradman can be heard in a 1930 recording saying "I have always endeavoured to do my best for the side, and the few centuries that have come my way have been achieved in the hope of winning matches. My one idea when going into bat was to make runs for Australia."[25] In the Headingley Test, he made 334, reaching 309* at the end of the first day, including a century before lunch. Bradman himself thought that his 254 in the preceding match, at Lord's, was a better innings. England managed to stay in contention until the deciding final Test at The Oval, but yet another double hundred by Bradman, and 7/92 by Percy Hornibrook in England's second innings, enabled Australia to win by an innings and take the series 2–1. Clarrie Grimmett's 29 wickets at 31.89 for Australia in this high-scoring series were also important.

Australia had one of the strongest batting line-ups ever in the early 1930s, with Bradman, Archie Jackson, Stan McCabe, Bill Woodfull and Bill Ponsford. It was the prospect of bowling at this line-up that caused England's 1932–33 captain Douglas Jardine to adopt the tactic of fast leg theory, better known as Bodyline.

Jardine instructed his fast bowlers, most notably Harold Larwood and Bill Voce, to bowl at the bodies of the Australian batsmen, with the goal of forcing them to defend their bodies with their bats, thus providing easy catches to a stacked leg-side field. Jardine insisted that the tactic was legitimate and called it "leg theory" but it was widely disparaged by its opponents, who dubbed it "Bodyline" (from "on the line of the body"). Although England decisively won the Ashes 4–1, Bodyline caused such a furore in Australia that diplomats had to intervene to prevent serious harm to Anglo-Australian relations, and the MCC eventually changed the Laws of cricket to curtail the number of leg side fielders.

Jardine's comment was: "I've not travelled 6,000 miles to make friends. I'm here to win the Ashes".[26]

Some of the Australians wanted to use Bodyline in retaliation, but Woodfull flatly refused. He famously told England manager Pelham Warner, "There are two teams out there. One is playing cricket; the other is making no attempt to do so" after the latter had come into the Australian rooms to express sympathy after a Larwood bouncer had struck the Australian skipper in the heart and felled him.[27]

1934 to 1953

On the batting-friendly wickets that prevailed in the late 1930s, most Tests up to the Second World War still gave results. It should be borne in mind that Tests in Australia prior to the war were all played to a finish, with many batting records set during this period.

The 1934 Ashes series began with the notable absence of Larwood, Voce and Jardine. The MCC had made it clear, in light of the revelations of the bodyline series, that these players would not face Australia. The MCC, although it had earlier condoned and encouraged[28] bodyline tactics in the 1932–33 series, laid the blame on Larwood when relations turned sour. Larwood was forced by the MCC to either apologise or be removed from the Test side. He went for the latter.

Australia recovered the Ashes in 1934 and held them until 1953, though no Test cricket was played during the Second World War.

As in 1930, the 1934 series was decided in the final Test at The Oval. Australia, batting first, posted a massive 701 in the first innings. Bradman (244) and Ponsford (266) were in record-breaking form with a partnership of 451 for the second wicket. England eventually faced a massive 707-run target for victory and failed, Australia winning the series 2–1.[29] This made Woodfull the only captain to regain the Ashes and he retired upon his return to Australia.

In 1936–37 Bradman succeeded Woodfull as Australian captain. He started badly, losing the first two Tests heavily after Australia were caught on sticky wickets. However, the Australians fought back and Bradman won his first series in charge 3–2.

The 1938 series was a high-scoring affair with two high-scoring draws, resulting in a 1–1 result, Australia retaining the Ashes. After the first two matches ended in stalemate and the Third Test at Old Trafford never started due to rain, Australia then scraped home by five wickets inside three days in a low-scoring match at Headingley to retain the urn. In the timeless Fifth Test at The Oval, the highlight was Len Hutton's then world-record score of 364 as England made 903-7 declared. Bradman and Jack Fingleton injured themselves during Hutton's marathon effort, and with only nine men, Australia fell to defeat by an innings and 579 runs,[30] the heaviest in Test history.

The Ashes resumed after the war when England toured in 1946–47 and, as in 1920–21, found that Australia had made the better post-war recovery. Still captained by Bradman and now featuring the potent new-ball partnership of Ray Lindwall and Keith Miller, Australia were convincing 3–0 winners.

Aged 38 and having been unwell during the war, Bradman had been reluctant to play. He batted unconvincingly and reached 28 when he hit a ball to Jack Ikin; England believed it was a catch, but Bradman stood his ground, believing it to be a bump ball. The umpire ruled in the Australian captain's favour and he appeared to regain his fluency of yesteryear, scoring 187. Australia promptly seized the initiative, won the First Test convincingly and inaugurated a dominant post-war era. The controversy over the Ikin catch was one of the biggest disputes of the era.

In 1948, Australia set new standards, completely outplaying its hosts to win 4–0 with one draw. This Australian team, led by Bradman, who turned 40 during his final tour of England, has gone down in history as The Invincibles. Playing 34 matches on tour—three of which were not first-class—and including the five Tests, they remained unbeaten, winning 27 and drawing 7.

Bradman's men were greeted by packed crowds across the country, and records for Test attendances in England were set in the Second and Fourth Tests at Lord's and Headingley respectively. Before a record attendance of spectators at Headingley, Australia set a world record by chasing down 404 on the last day for a seven-wicket victory.

The 1948 series ended with one of the most poignant moments in cricket history, as Bradman played his final innings for Australia in the Fifth Test at The Oval, needing to score only four runs to end with a career batting average of exactly 100. However, Bradman made a second-ball duck, bowled by an Eric Hollies googly[31] that sent him into retirement with a career average of 99.94.

Bradman was succeeded as Australian captain by Lindsay Hassett, who led the team to a 4–1 series victory in 1950–51. The series was not as one-sided as the number of wins suggest, with several tight matches.

The tide finally turned in 1953 when England won the final Test at The Oval to take the series 1–0, having narrowly avoided defeat in the preceding Test at Headingley. This was the beginning of one of the greatest periods in English cricket history with players such as captain Len Hutton, batsmen Denis Compton, Peter May, Tom Graveney, Colin Cowdrey, bowlers Fred Trueman, Brian Statham, Alec Bedser, Jim Laker, Tony Lock, wicket-keeper Godfrey Evans and all-rounder Trevor Bailey.

1954 to 1971

In 1954–55, Australia's batsmen had no answer to the pace of Frank Tyson and Statham. After winning the First Test by an innings after being controversially sent in by Hutton, Australia lost its way and England took a hat-trick of victories to win the series 3–1.[32]

A dramatic series in 1956 saw a record that will probably never be beaten: off-spinner Jim Laker's monumental effort at Old Trafford when he bowled 68 of 191 overs to take 19 out of 20 possible Australian wickets in the Fourth Test.[33] It was Australia's second consecutive innings defeat in a wet summer, and the hosts were in strong positions in the two drawn Tests, in which half the playing time was washed out. Bradman rated the team that won the series 2–1 as England's best ever.

England's dominance was not to last. Australia won 4–0 in 1958–59, having found a high-quality spinner of their own in new skipper Richie Benaud, who took 31 wickets in the five-Test series, and paceman Alan Davidson, who took 24 wickets at 19.00. The series was overshadowed by the furore over various Australian bowlers, most notably Ian Meckiff, whom the English management and media accused of illegally throwing Australia to victory.

In 1961, Australia won a hard-fought series 2–1, their first Ashes series win in England for 13 years. After narrowly winning the Second Test at Lord's, dubbed "The Battle of the Ridge" because of a protrusion on the pitch that caused erratic bounce, Australia mounted a comeback on the final day of the Fourth Test at Old Trafford and sealed the series with Richie Benaud taking 6-70 during the English runchase.

The tempo of the play changed over the next four series in the 1960s, held in 1962–63, 1964, 1965–66 and 1968. The powerful array of bowlers that both countries boasted in the preceding decade moved into retirement, and their replacements were of lesser quality, making it more difficult to force a result. England failed to win any series during the 1960s, a period dominated by draws as teams found it more prudent to save face than risk losing. Of the 20 Tests played during the four series, Australia won four and England three. As they held the Ashes, Australia's captains Bob Simpson and Bill Lawry were happy to adopt safety-first tactics and their strategy of sedate batting saw many draws. During this period, spectator attendances dropped and media condemnation increased, but Simpson and Lawry flatly disregarded the public dissatisfaction.

It was in the 1960s that the bipolar dominance of England and Australia in world cricket was seriously challenged for the first time. West Indies defeated England twice in the mid-1960s and South Africa, in two series before they were banned for apartheid, completely outplayed Australia 3–1 and 4–0. Australia had lost 2–1 during a tour of the West Indies in 1964–65, the first time it had lost a series to any team other than England.

In 1970–71, Ray Illingworth led England to a 2–0 win in Australia, mainly due to John Snow's fast bowling, and the prolific batting of Geoffrey Boycott and John Edrich. It was not until the last session of what was the 7th Test (one match having been abandoned without a ball bowled) that England's success was secured. Lawry was sacked after the Sixth Test after the selectors finally lost patience with Australia's lack of success and dour strategy. Lawry was not informed of the decision privately and heard his fate over the radio.[34]

1972 to 1987

The 1972 series finished 2–2, with England under Illingworth retaining the Ashes.[35]

In the 1974–75 series, with the England team breaking up and their best batsman Geoff Boycott refusing to play, Australian pace bowlers Jeff Thomson and Dennis Lillee wreaked havoc. A 4–1 result was a fair reflection as England were left shell shocked.[36] England then lost the 1975 series 0–1, but at least restored some pride under new captain Tony Greig.[37]

Australia won the 1977 Centenary Test[38] which was not an Ashes contest, but then a storm broke as Kerry Packer announced his intention to form World Series Cricket.[39] WSC affected all Test-playing nations but it weakened Australia especially as the bulk of its players had signed up with Packer; the Australian Cricket Board (ACB) would not select WSC-contracted players and an almost completely new Test team had to be formed. WSC came after an era during which the duopoly of Australian and English dominance dissipated; the Ashes had long been seen as a cricket world championship but the rise of the West Indies in the late 1970s challenged that view. The West Indies would go on to record resounding Test series wins over Australia and England and dominated world cricket until the 1990s.

With Greig having joined WSC, England appointed Mike Brearley as its captain and he enjoyed great success against Australia. Largely assisted by the return of Boycott, Brearley's men won the 1977 series 3–0 and then completed an overwhelming 5–1 series win against an Australian side missing its WSC players in 1978–79. Allan Border made his Test debut for Australia in 1978–79.

Brearley retired from Test cricket in 1980 and was succeeded by Ian Botham, who started the 1981 series as England captain, by which time the WSC split had ended. After Australia took a 1–0 lead in the first two Tests, Botham was forced to resign or was sacked (depending on the source). Brearley surprisingly agreed to be reappointed before the Third Test at Headingley. This was a remarkable match in which Australia looked certain to take a 2–0 series lead after it had forced England to follow-on 227 runs behind. England, despite being 135 for 7, produced a second innings total of 356, Botham scoring 149*. Chasing just 130, Australia were sensationally dismissed for 111, Bob Willis taking 8–43. It was the first time since 1894–95 that a team following on had won a Test match. Under Brearley's leadership, England went on to win the next two matches before a drawn final match at The Oval.[40]

In 1982–83 Australia had Greg Chappell back from WSC as captain, while the England team was weakened by the enforced omission of their South African tour rebels, particularly Graham Gooch and John Emburey. Australia went 2–0 up after three Tests, but England won the Fourth Test by 3 runs (after a 70-run last wicket stand) to set up the final decider, which was drawn.[41]

In 1985, David Gower's England team was strengthened by the return of Gooch and Emburey as well as the emergence at international level of Tim Robinson and Mike Gatting. Australia, now captained by Allan Border, had itself been weakened by a rebel South African tour, the loss of Terry Alderman being a particular factor. England won 3–1.

Despite suffering heavy defeats against the West Indies during the 1980s, England continued to do well in the Ashes. Mike Gatting was the captain in 1986–87 but his team started badly and attracted some criticism.[42] Then Chris Broad scored three hundreds in successive Tests and bowling successes from Graham Dilley and Gladstone Small meant England won the series 2–1.[43]

1989 to 2003

The Australian team of 1989 was comparable to the great Australian teams of the past, and resoundingly defeated England 4–0.[44] Well led by Allan Border, the team included the young cricketers Mark Taylor, Merv Hughes, David Boon, Ian Healy and Steve Waugh, who were all to prove long-serving and successful Ashes competitors. England, now led once again by David Gower, suffered from injuries and poor form. During the Fourth Test news broke that prominent England players had agreed to take part in a "rebel tour" of South Africa the following winter; three of them (Tim Robinson, Neil Foster and John Emburey) were playing in the match, and were subsequently dropped from the England side.[45]

Australia reached a cricketing peak in the 1990s and early 2000s, coupled with a general decline in England's fortunes. After re-establishing its credibility in 1989, Australia underlined its superiority with victories in the 1990–91, 1993, 1994–95, 1997, 1998–99, 2001 and 2002–03 series, all by convincing margins.

Great Australian players in the early years included batsmen Border, Boon, Taylor and Steve Waugh. The captaincy passed from Border to Taylor in the mid-1990s and then to Steve Waugh before the 2001 series. In the latter part of the 1990s Waugh himself, along with his twin brother Mark, scored heavily for Australia and fast bowlers Glenn McGrath and Jason Gillespie made a serious impact, especially the former. The wicketkeeper-batsman position was held by Ian Healy for most of the 1990s and by Adam Gilchrist from 2001 to 2006–07. In the 2000s, batsmen Justin Langer, Damien Martyn and Matthew Hayden became noted players for Australia. But the most dominant Australian player was leg-spinner Shane Warne, whose first delivery in Ashes cricket in 1993, to dismiss Mike Gatting, became known as the Ball of the Century.

Australia's record between 1989 and 2005 had a significant impact on the statistics between the two sides. Before the 1989 series began, the win–loss ratio was almost even, with 87 test wins for Australia to England's 86, 74 tests having been drawn.[46] By the 2005 series Australia's test wins had increased to 115 whereas England's had increased to only 93 (with 82 draws).[47] In the period between 1989 and the beginning of the 2005 series, the two sides had played 43 times; Australia winning 28 times, England 7 times, with 8 draws. Only a single England victory had come in a match in which the Ashes were still at stake, namely the First Test of the 1997 series. All others were consolation victories when the Ashes had been secured by Australia.[48]

2005 to 2015

England were undefeated in Test matches through the 2004 calendar year. This elevated them to second in the ICC Test Championship. Hopes that the 2005 Ashes series would be closely fought proved well-founded, the series remaining undecided as the closing session of the final Test began. Experienced journalists including Richie Benaud rated the series as the most exciting in living memory. It has been compared with the great series of the distant past, such as 1894–95 and 1902.[49]

The First Test at Lord's was convincingly won by Australia, but in the remaining four matches the teams were evenly matched and England fought back to win the Second Test by 2 runs, the smallest winning margin in Ashes history, and the second-smallest in all Tests. The rain-affected Third Test ended with the last two Australian batsmen holding out for a draw; and England won the Fourth Test by three wickets after forcing Australia to follow-on for the first time in 191 Tests. A draw in the final Test gave England victory in an Ashes series for the first time in 18 years and their first Ashes victory at home since 1985.

Australia regained the Ashes on its home turf in the 2006–07 series with a convincing 5–0 victory, only the second time an Ashes series had been won by that margin. Glenn McGrath, Shane Warne and Justin Langer retired from Test cricket after that series, while Damien Martyn retired during the series.[50]

The 2009 series began with a tense draw in the First Test at SWALEC Stadium in Cardiff, with England's last-wicket batsmen James Anderson and Monty Panesar surviving 69 balls. England then achieved its first Ashes win at Lord's since 1934 to go 1–0 up. After a rain-affected draw at Edgbaston, the fourth match at Headingley was convincingly won by Australia by an innings and 80 runs to level the series. Finally, England won the Fifth Test at The Oval by a margin of 197 runs to regain the Ashes. Andrew Flintoff retired from Test cricket soon afterwards.

The 2010–11 series was played in Australia. The First Test at Brisbane ended in a draw, but England won the Second Test, at Adelaide, by an innings and 71 runs. Australia came back with a victory at Perth in the Third Test. In the Fourth Test at Melbourne Cricket Ground, England batting second scored 513 to defeat Australia (98 and 258) by an innings and 157 runs. This gave England an unbeatable 2–1 lead in the series and so it retained the Ashes. England went on to win the series 3–1, beating Australia by an innings and 83 runs at Sydney in the Fifth Test, including their highest innings total since 1938 (644). England's series victory was its first on Australian soil for 24 years. The 2010–11 Ashes series was the only one in which a team had won three Tests by innings margins and it was the first time England had scored 500 or more four times in a single series.

Australia's build-up to the 2013 Ashes series was far from ideal. Darren Lehmann took over as coach from Mickey Arthur[51] following a string of poor results. A batting line-up weakened by the previous year's retirements of former captain Ricky Ponting and Mike Hussey was also shorn of opener David Warner, who was suspended for the start of the series following an off-field incident.[52] England won a closely fought First Test by 14 runs, despite 19-year-old debutant Ashton Agar making a world-record 98 for a number 11 in the first innings. England then won a very one-sided Second Test by 347 runs while the rain-affected Third Test, held at a newly refurbished Old Trafford, was drawn, ensuring that England retained the Ashes.[53] England won the Fourth Test by 74 runs after Australia lost their last eight second-innings wickets for only 86 runs. The final Test was drawn,[54] giving England a 3–0 series win.

In the second of two Ashes series held in 2013 (the series ended in 2014), this time hosted by Australia, the home team won the series five test matches to nil. This was the third time Australia has completed a clean sweep (or "whitewash") in Ashes history, a feat never matched by England. All six Australian specialist batsmen scored more runs than any Englishman with 10 centuries among them, with only debutant Ben Stokes scoring a century for England. Mitchell Johnson took 37 English wickets at 13.97 and Ryan Harris 22 wickets at 19.31 in the 5-Test series.[55] Only Stuart Broad and all-rounder Stokes bowled effectively for England, with their spinner Graeme Swann retiring due to a chronic elbow injury after the decisive Third Test.

Australia came into the 2015 Ashes series in England as favourites to retain the Ashes. Although England won the first Test in Cardiff, Australia won comfortably in the second Test at Lords. In the next two Tests, the Australian batsmen struggled, being bowled out for 136 in the first innings at Edgbaston, with England proceeding to win by eight wickets. This was followed by Australia being bowled out for 60 as Stuart Broad took five wickets and finished the spell with 8 for 15 in the first innings at Trent Bridge, the quickest – in terms of balls faced – a team has been bowled out in the first innings of a Test match. With victory by an innings and 78 runs on the morning of the third day of the Fourth Test, England regained the Ashes.

2017 to present

During the buildup, the 2017–18 Ashes series was regarded as a turning point for both sides. Australia were criticised for being too reliant on captain Steve Smith and vice-captain David Warner, while England was said to have a shoddy middle to lower order.[56] Off the field, England all-rounder Ben Stokes was ruled out of the side indefinitely due to a police investigation.

Australia won the first Test match in Brisbane by 10 wickets[57] and the second Test at Adelaide by 120 runs in the first ever day-night Ashes test match. Australia regained The Ashes with an innings and 41 run win in the third Test at Perth; the final Ashes Test at the WACA Ground.[58]

Prior to the 2019 Ashes series, both teams were considered to have very strong bowling attacks but struggling batting orders. Australia had its top-order batsmen David Warner, Steve Smith and Cameron Bancroft available for international selection after being banned from international cricket for 9–12 months following the ball-tampering scandal in South Africa, during which time India had won its first ever Test series in Australia.[59] However, Australia recovered to win the Test series against Sri Lanka 2–0.[60]

Despite winning the Cricket World Cup in July 2019 for the first time, England had also been criticised for its fragile top-order in Tests. The retirement of opener Alastair Cook in August 2018 ensured potential top-order batsmen Rory Burns, Joe Denly and Jason Roy were able to secure a place in the side. Despite losing a Test series 2–1 in their tour of the West Indies,[61] England then improved to win the one-off Test against Ireland, by 143 runs. The 2019 series was eventually drawn 2–2, with Australia retaining the Ashes.

The 2021 Ashes series was played from December 2021 through January 2022,[62] and featured the first Ashes test match to be played in Tasmania, at Hobart's Bellerive Oval.[63] Australia retained the Ashes in the 2021-22 Ashes series, after Scott Boland achieved the third best bowling figures in the history of Australian cricket at 6-7 (4 overs). [64]

Summary of results and statistics

In the 138 years since 1883, Australia have held the Ashes for approximately 82.5 years, and England for 55.5 years:

|

Test results, up to and including the 2021-22 Ashes series in Australia:[65][note 1]

| Overall Test Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tests played | Draws | ||

| 356 | 150 | 110 | 96 |

Series results, up to and including the 2021-22 Ashes series:

| Overall Series Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Series played | Draws | ||

| 72 | 34 | 32 | 6 |

A team must win a series to gain the right to hold the Ashes. A drawn series results in the previous holders retaining the Ashes. Ashes series have generally been played over five Test matches, although there have been four-match series (1938 and 1975) and six-match series (1970–71, 1974–75, 1978–79, 1981, 1985, 1989, 1993 and 1997). Australians have made 264 centuries in Ashes Tests, of which 23 have been scores over 200, while Englishmen have scored 212 centuries, of which 10 have been over 200. Australians have taken 10 wickets in a match on 41 occasions, Englishmen 38 times.

Match venues

The series alternates between England (and Wales) and Australia, and each match of a series is held at a different ground.

In Australia, the grounds currently used are The Gabba in Brisbane (first staged an England–Australia Test in the 1932–33 season), Adelaide Oval (1884–85), the Melbourne Cricket Ground (MCG) (1876–77), and the Sydney Cricket Ground (SCG) (1881–82). A single Test was held at the Brisbane Exhibition Ground in 1928–29. Traditionally, Melbourne hosts the Boxing Day Test and Sydney hosts the New Year's Day Test. Additionally the WACA in Perth (1970–71) hosted its final Ashes Test in 2017–18 and was due to be replaced by Perth Stadium for the 2021–22 series. However, Western Australian border restrictions and quarantine requirements during the COVID-19 pandemic led to a change in venue for the final Ashes Test to Bellerive Oval in Hobart. This was the first Ashes Test match to be held in Tasmania.

Cricket Australia proposed that the 2010–11 series consist of six Tests, with the additional game to be played at Bellerive Oval in Hobart. The England and Wales Cricket Board declined and the series was played over five Tests.

In England and Wales, the grounds currently used are: Old Trafford in Manchester (1884), The Oval in Kennington, South London (1884); Lord's in St John's Wood, North London (1884); Headingley in Leeds (1899) and Edgbaston in Birmingham (1902). Additionally Sophia Gardens in Cardiff, Wales (2009); the Riverside Ground in Chester-le-Street, County Durham (2013) and Trent Bridge at West Bridgford (1899), have been used and one Test was also held at Bramall Lane in Sheffield in 1902. Traditionally the final Test of the series is played at the Oval. Sophia Gardens and the Riverside were excluded as Test grounds between the years of 2020 and 2024 and therefore will not host an Ashes Test until at least 2027. Trent Bridge is also not due to host an Ashes Test until 2027.

| In Australia | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stadium | State | First Test | Last Test | Played | Draws* | Ref | |||||||

| MCG, Melbourne | 1882–83 | 2021–22 | 51 | 27 | 2021 | 7 | 19 | 2010 | [66] | ||||

| SCG, Sydney | 1882–83 | 2021–22 | 52 | 23 | 2018 | 7 | 22 | 2011 | [67] | ||||

| Adelaide Oval, Adelaide | 1884–85 | 2021–22 | 33 | 19 | 2021 | 5 | 9 | 2010 | [68] | ||||

| Brisbane Exhibition Ground, Brisbane‡ | 1928–29 | 1928–29 | 1 | 0 | – | 0 | 1 | 1928 | [69] | ||||

| The Gabba, Brisbane | 1932–33 | 2021–22 | 22 | 13 | 2021 | 5 | 4 | 1986 | [70] | ||||

| WACA Ground, Perth‡ | 1970–71 | 2017–18 | 13 | 9 | 2017 | 3 | 1 | 1978 | [71] | ||||

| Bellerive Oval, Hobart | 2021–22 | 2021–22 | 1 | 1 | 2021 | 0 | 0 | - | [72] | ||||

| In England | |||||||||||||

| Stadium | County† | First Test | Last Test | Played | Draws* | Ref | |||||||

| Old Trafford, Manchester | 1884 | 2019 | 32 | 7 | 1981 | 17 | 8 | 2019 | [73] | ||||

| Lord's, London | 1884 | 2019 | 38 | 7 | 2013 | 15 | 16 | 2015 | [74] | ||||

| The Oval, London | 1884 | 2019 | 36 | 16 | 2019 | 14 | 6 | 2015 | [75] | ||||

| Trent Bridge, Nottingham | 1899 | 2015 | 22 | 6 | 2015 | 9 | 7 | 2001 | [76] | ||||

| Headingley, Leeds | 1899 | 2019 | 25 | 8 | 2019 | 8 | 9 | 2009 | [77] | ||||

| Edgbaston, Birmingham | 1902 | 2019 | 15 | 6 | 2015 | 5 | 4 | 2019 | [78] | ||||

| Bramall Lane, Sheffield‡ | 1902 | 1902 | 1 | 0 | – | 0 | 1 | 1902 | [79] | ||||

| Sophia Gardens, Cardiff | 2009 | 2015 | 2 | 1 | 2015 | 1 | 0 | – | [80] | ||||

| The Riverside, Chester-le-Street | 2013 | 2013 | 1 | 1 | 2013 | 0 | 0 | – | [81] | ||||

*Including abandoned tests

†County cricket clubs who play at the grounds

‡Former grounds which no longer host Test Matches

Cultural references

.jpg.webp)

The popularity and reputation of the cricket series has led to other sports and games using the name "Ashes" for contests between England and Australia. The best-known and longest-running of these events is the rugby league rivalry between Great Britain and Australia (see rugby league "Ashes"). Use of the name "Ashes" was suggested by the Australian team when rugby league matches between the two countries commenced in 1908. Other examples included the television game shows Gladiators and Sale of the Century, both of which broadcast special editions containing contestants from the Australian and English versions of the shows competing against each other.

The term became further genericised in Australia in the first half of the twentieth century, and was used to describe many sports rivalries or competitions outside the context of Australia vs England. The Australian rules football interstate carnival, and the small silver casket which served as its trophy, were symbolically known as "the Ashes" of Australian football,[82] and was spoken of as such until at least the 1940s.[83] The soccer rivalry between Australia and New Zealand was described as "the soccer ashes of Australasia" until as late as the 1950s;[84] ashes from cigars smoked by the two countries' captains were put into a casket in 1923 to make the trophy literal.[85] The interstate rugby league rivalry between Queensland and New South Wales was known for a time as Australia's rugby league ashes, and bowls competitions between the two states also regularly used the term.[86] Even some local rivalries, such as southern Western Australia's annual Great Southern Football Carnival, were locally described as "the ashes".[87] This genericised usage is no longer common, and "the Ashes" would today be assumed only to apply to a contest between Australia and England.

The Ashes featured in the film The Final Test, released in 1953, based on a television play by Terence Rattigan. It stars Jack Warner as an England cricketer playing the last Test of his career, which is the last of an Ashes series; the film includes cameo appearances of English captain Len Hutton and other players[88] who were part of England's 1953 triumph.

Douglas Adams's 1982 science fiction comedy novel Life, the Universe and Everything – the third part of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy series – features the urn containing the Ashes as a significant element of its plot. The urn is stolen by alien robots, as the burnt stump inside is part of a key needed to unlock the "Wikkit Gate" and release an imprisoned world called Krikkit.

Bodyline, a fictionalised television miniseries based on the "Bodyline" Ashes series of 1932–33, was screened in Australia in 1984. The cast included Gary Sweet as Donald Bradman and Hugo Weaving as England captain Douglas Jardine.[89]

In the 1938 film The Lady Vanishes, Charters and Caldicott, played by Basil Radford and Naunton Wayne are two cricket fans who are desperate to get home from Europe in order to see the last day's play in the 3rd Test at Manchester. It is not until they see a newsboy's poster near the end of the film that they discover that the match had been abandoned, due to floods.

See also

- History of Test cricket from 1877 to 1883

- History of Test cricket from 1884 to 1889

- History of Test cricket from 1890 to 1900

Notes

- Australia and England have played an additional 16 Tests: five prior to the Ashes, and 11 where the Ashes were not at stake. Including these Tests, the win–loss record stands at 150 Australian wins, 110 English wins, and 96 draws (up to and including the 5th Test of the 2021-22 series). See Cricinfo statistics.

References

- Wendy Lewis; Simon Balderstone & John Bowan (2006). Events That Shaped Australia. New Holland. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-74110-492-9.

- Summary of Events The Illustrated Australian News, 20 February 1884, (foot of column 2) at Trove

- Cricket Hobart Mercury, 4 June 1908, p.8, at Trove

- "The Ashes History". Lords. Archived from the original on 9 October 2018. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- Fred Spofforth, however, contended that, the fourth innings aside, it played perfectly well.

- Worrall, Jack (23 August 1930). "A Great Bowlers' Victory". Daily News. Perth, WA. p. 11. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- Hilton, Christopher (2006). The birth of the Ashes : the amazing story of the first Ashes test. Banksmeadow, N.S.W.: Renniks Publications. ISBN 978-0-9752245-4-0. OCLC 123232899.

- Wisden on the Ashes : the authoritative story of cricket's greatest rivalry : updated to include the 2015 series. Steven Lynch. London. 2015. ISBN 978-1-4729-1353-1. OCLC 930079935.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Gibson, A., Cricket Captains of England, p. 26.

- Willis, Ronald (1982). Cricket's Biggest Mystery: The Ashes. ISBN 0-7270-1768-3.

- Munns, Joy (1994). Beyond Reasonable Doubt: The birthplace of the Ashes. ISBN 0-646-22153-1.

- "Sunday Times (Perth) 15 August 1926 page 9S. Online Reference". Trove.nla.gov.au. 15 August 1926. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- The Times (London), 27 June 1930. page 7.

- "Geraldton Guardian 15 February 1921, page 1. Online reference". Trove.nla.gov.au. 15 February 1921. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- "Brisbane Courier, 9 June 1926, page 7. Online reference". Trove.nla.gov.au. 9 June 1926. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- "Ashes urn heads to Australia". BBC Sport. 15 October 2006. Retrieved 8 November 2007.

- "What is the Ashes Trophy?" Archived 10 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Lord's website. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- "Wisden – The glorious uncertainty". espncricinfo.com. 29 June 2019.

- Plum Warner, How We Recovered The Ashes, Longman, 1905

- Harte, pp. 251–256.

- Harte, pp. 274–276.

- "Statsguru – Australia – Tests – Results list". Cricinfo. Retrieved 21 December 2007.

- Harte, pp. 298–301.

- Harte, pp. 312–316.

- "Don Bradman in 'The 1930 Australian XI: Winners of the Ashes'". Aso.gov.au. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- Kidd, Patrick (4 September 2007). "Top 50 British achievements". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 21 August 2008.

- Cashman; Franks; Maxwell; Sainsbury; Stoddart; Weaver; Webster (1997). The A-Z of Australian cricketers. pp. 322–323.

- Frith, David (2002). Bodyline autopsy: the full story of the most sensational test cricket series: Australia vs England 1932-33. Sydney: ABC Books for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. p. 47. ISBN 0733311725.

- Harte, pp. 356–357.

- Classic Ashes clashes – 1938, The Oval at BBC Sport, 5 November 2006. Accessed 4 March 2006

- 1948 – Bradman's final innings duck at BBC Sport, 27 May 2009. Accessed 4 March 2015

- Harte, pp. 435–437.

- Harte, pp. 444–446.

- Harte, pp. 526–530.

- Harte, pp. 538–540.

- Harte, pp. 557–559.

- Harte, pp. 561–563.

- Harte, pp. 580–581.

- Harte, pp. 579–590

- Harte, pp. 627–628.

- Harte, pp. 636–637.

- Miller, Andrew; Martin Williamson (16 November 2006). "Can't bat, can't bowl, can't field". Cricinfo. Retrieved 8 November 2007.

- Harte, pp. 662–664.

- Harte, pp. 679–682.

- Hoult, Nick (July 2004). "Rebels take a step too far (English rebel tour to South Africa, 1989)". Cricinfo. Retrieved 22 October 2007.

- "Team records | Test matches | Cricinfo Statsguru | ESPN Cricinfo". Stats.cricinfo.com. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- "Team records | Test matches | Cricinfo Statsguru | ESPN Cricinfo". Stats.cricinfo.com. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- "Cricinfo – Statsguru – Australia – Tests – Series record". Stats.cricinfo.com. 17 June 2008. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- "THE ASHES, a battle of wills between English and Australian Cricket". sport.y2u.co.uk. Archived from the original on 4 January 2016. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- "Damien Martyn". cricinfo.

- Ashes 2013: Darren Lehmann replaces Mickey Arthur as Australia coach; Clarke steps down as selector at ABC News, 24 June 2013. Retrieved 24 June 2013

- "Ashes 2013: David Warner set for southern Africa match practice". BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. 10 July 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- Sheringham, Sam (5 August 2013). "Ashes 2013: England retain Ashes as rain forces Old Trafford draw". BBC Sport. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- "Ashes 2013: Ashes 2013: England win series 3–0 after bad light ends Oval Test". BBC Sport. 25 August 2013. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- "The best series for fast bowlers". Cricinfo. 10 January 2014. Archived from the original on 9 November 2015. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- "Australia over-reliant on Smith, Warner, feels Slater". CricBuzz.

- "Ashes: Australia beat England by 10 wickets in first Test". 27 November 2017 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- "Ruthless Australia regain the Ashes". Cricket Australia. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- "India secure historic series victory". International Cricket Council. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- "Starc takes ten as Australia sweep series". International Cricket Council. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- "England in West Indies: Tourists claim consolation 232-run victory as hosts win series 2-1". BBC Sport. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- "Fixture confirmed for dual Ashes series, Afghan Test". Cricket Australia. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- "Tasmanians gather to watch historic fifth Ashes Test at Bellerive Oval in Hobart". ABC News. 14 January 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- "Australia Vs England Ashes 3rd Test Scorecard". ESPN Cricinfo. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- "Team records | Test matches | Cricinfo Statsguru | ESPN Cricinfo". Stats.cricinfo.com. 1 January 1970. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- "Melbourne Cricket Ground". ESPN Cricinfo. 9 December 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- "Sydney Cricket Ground". ESPN Cricinfo. 9 December 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- "Adelaide Oval". ESPN Cricinfo. 9 December 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- "Brisbane Exhibition Ground". ESPN Cricinfo. 9 December 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- "The Gabba". ESPN Cricinfo. 9 December 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- "WACA Ground". ESPN Cricinfo. 9 December 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- "Bellerive Oval". ESPN Cricinfo. 9 December 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- "Old Trafford". ESPN Cricinfo. 9 December 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- "Lord's". ESPN Cricinfo. 9 December 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- "The Oval". ESPN Cricinfo. 9 December 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- "Trent Bridge". ESPN Cricinfo. 9 December 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- "Headingley". ESPN Cricinfo. 9 December 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- "Edgbaston". ESPN Cricinfo. 9 December 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- "Bramall Lane". ESPN Cricinfo. 9 December 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- "Sophia Gardens". ESPN Cricinfo. 9 December 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- "The Riverside". ESPN Cricinfo. 9 December 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- "Carnival champions – presentation of the Ashes". Daily Herald. Adelaide, SA. p. 9.

- "Victoria's football ashes". Barrier Daily Truth. Broken Hill, NSW. 11 August 1947. p. 6.

- J. O. Wishaw (25 August 1954). "Kiwis to win the Ashes". The Sporting Globe. Melbourne, VIC. p. 7.

- "The soccer ashes of Australasia". Referee. Sydney, NSW. 16 April 1924. p. 16.

- "Bowls – N.S.W. "Knuts" retain the "Ashes"". The Brisbane Courier. Brisbane, QLD. 14 July 1920. p. 3.

- "Great Southern Football Carnival". Great Southern Herald. Katanning, WA. 21 September 1935. p. 3.

- "The Final Test (1953)". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- Frith, David (24 June 2013). Bodyline Autopsy: The full story of the most sensational Test cricket series: Australia v England 1932–33. Aurum Press. ISBN 9781781311936.

Further reading

- Berry, S. (2006). Cricket's Burning Passion. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-413-77627-1.

- Birley, D. (2003). A Social History of English Cricket. London: Aurum Press. ISBN 1-85410-941-3.

- Frith, D. (1990). Australia versus England: a pictorial history of every Test match since 1877. Victoria (Australia): Penguin Books. ISBN 0-670-90323-X.

- Gibb, J. (1979). Test cricket records from 1877. London: Collins. ISBN 0-00-411690-9.

- Gibson, A. (1989). Cricket Captains of England. London: Pavilion Books. ISBN 1-85145-395-4.

- Green, B. (1979). Wisden Anthology 1864–1900. London: M & J/QA Press. ISBN 0-356-10732-9.

- Harte, Chris (2003). Penguin history of Australian cricket. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-670-04133-5.

- Munns, J. (1994). Beyond reasonable doubt – Rupertswood, Sunbury – the birthplace of the Ashes. Australia: Joy Munns. ISBN 0-646-22153-1.

- Warner, P. (1987). Lord's 1787–1945. London: Pavilion Books. ISBN 1-85145-112-9.

- Warner, P. (2004). How we recovered the Ashes: MCC Tour 1903–1904. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-413-77399-X.

- Willis, R. Cricket's Biggest Mystery: The Ashes Archived 14 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine, The Lutterworth Press (1987), ISBN 978-0-7188-2588-1.

- Wynne-Thomas, P. (1989). The complete history of cricket tours at home and abroad. London: Hamlyn. ISBN 0-600-55782-0.

Other

- Wisden's Cricketers Almanack (various editions)

External links

- Ashes to Ashes An audio history of the first hundred years of the Ashes, narrated by John Arlott

- Cricinfo's Ashes website

- The Origin of the Ashes – Rex Harcourt

- Listen to a young Don Bradman speaking after the 1930 Ashes tour