The Good Earth

The Good Earth is a historical fiction novel by Pearl S. Buck published in 1931 that dramatizes family life in a Chinese village in the early 20th century. It is the first book in her House of Earth trilogy, continued in Sons (1932) and A House Divided (1935). It was the best-selling novel in the United States in both 1931 and 1932, won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1932, and was influential in Buck's winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1938. Buck, who grew up in China as the daughter of American missionaries, wrote the book while living in China and drew on her first-hand observation of Chinese village life. The realistic and sympathetic depiction of the farmer Wang Lung and his wife O-Lan helped prepare Americans of the 1930s to consider Chinese as allies in the coming war with Japan.[1]

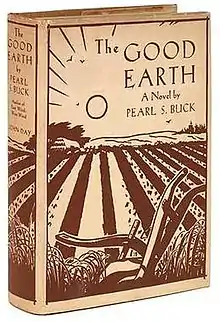

First edition | |

| Author | Pearl S. Buck |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Matthew Louie |

| Country | China |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Historical fiction |

| Publisher | John Day |

Publication date | March 2, 1931 |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 356 (1st edition) |

| OCLC | 565613765 |

| 813.52 | |

| Followed by | Sons |

The novel was included in Life Magazine's list of the 100 outstanding books of 1924–1944.[2] In 2004, the book returned to the bestseller list when chosen by the television host Oprah Winfrey for Oprah's Book Club.[3]

A Broadway stage adaptation was produced by the Theatre Guild in 1932, written by the father and son playwriting team of Owen and Donald Davis, but critics gave a poor reception, and it ran only 56 performances. However, the 1937 film, The Good Earth, which was based on the stage version, was more successful.

Plot

The story begins on Wang Lung's wedding day and follows the rise and fall of his fortunes. The House of Hwang, a family of wealthy landowners, lives in the nearby town, where Wang Lung's future wife, O-Lan, lives as a slave. However, the House of Hwang slowly declines due to opium use, frequent spending, uncontrolled borrowing and a general unwillingness to work.

Following the marriage of Wang Lung and O-Lan, both work hard on their farm and slowly save enough money to buy one plot of land at a time from the Hwang family. O-Lan delivers three sons and three daughters; the first daughter becomes mentally handicapped as a result of severe malnutrition brought on by famine. Her father greatly pities her and calls her "Poor Fool", a name by which she is addressed throughout her life. O-Lan kills her second daughter at birth to spare her the misery of growing up in such hard times, and to give the remaining family a better chance to survive.

During the devastating famine and drought, the family must flee to a large city in the south to find work. Wang Lung's malevolent uncle offers to buy his possessions and land, but for significantly less than their value. The family sells everything except the land and the house. Wang Lung then faces the long journey south, contemplating how the family will survive walking, when he discovers that the "firewagon" (the Chinese word for the newly built train) takes people south for a fee.

In the city, O-Lan and the children beg while Wang Lung pulls a rickshaw. Wang Lung's father begs but does not earn any money, and sits looking at the city instead. They find themselves aliens among their more metropolitan countrymen who look different and speak in a fast accent. They no longer starve, due to the one-cent charitable meals of congee, but still live in abject poverty. Wang Lung longs to return to his land. When armies approach the city he can only work at night hauling merchandise out of fear of being conscripted. One time, his son brings home stolen meat. Furious, Wang Lung throws the meat on the ground, not wanting his sons to grow up as thieves. O-Lan, however, calmly picks up the meat and cooks it. When a food riot erupts, Wang Lung is swept up in a mob that is looting a rich man's house and corners the man himself, who fears for his life and gives Wang Lung all his money in order to buy his safety. O-Lan finds a cache of jewels elsewhere in the house and takes them for herself.

Wang Lung uses this money to bring the family home, buy a new ox and farm tools, and hire servants to work the land for him. In time, two more children are born, a twin son and daughter. When he discovers the jewels that O-Lan looted, Wang Lung buys the House of Hwang's remaining land. He later sends his first two sons to school, also apprenticing the second one to a merchant, and retains the third one on the land.

As Wang Lung becomes more prosperous, he buys a concubine named Lotus. O-Lan endures the betrayal of her husband when he takes the only jewels she had asked to keep for herself, two pearls, so that he can make them into earrings to present to Lotus. O-Lan's health and morale deteriorate, and she eventually dies just after witnessing her first son's wedding. Wang Lung finally appreciates her place in his life as he mourns her passing.

Wang Lung and his family move into town and rent the old House of Hwang. Now an old man, he desires peace within his family but is annoyed by constant disputes, especially between his first and second sons and their wives. Wang Lung's third son runs away to become a soldier. At the end of the novel, Wang Lung overhears his sons planning to sell the land and tries to dissuade them. They say they will do as he wishes, but smile knowingly at each other.

Characters

- Wang Lung – poor, hard-working farmer born and raised in a small village of Anwhei (written as Anhui in pinyin) is the protagonist of the story and suffers hardships as he accumulates wealth and the outward signs of success. He has a strong sense of morality and adheres to Chinese traditions such as filial piety and duty to family. He believes that the land is the source of his happiness and wealth. By the end of his life he has become a very successful man and possesses a large plot of land which he buys from the House of Hwang. As his lifestyle changes he begins to indulge in the pleasures his wealth can buy—he purchases a concubine named Lotus. In Pinyin, Wang's name is written "Wang Long."[4] Wang is likely to be the common surname "Wang" represented by the character 王.

- O-Lan – first wife, formerly a slave in the house of Hwang. A woman of few words, she is uneducated but nonetheless is valuable to Wang Lung for her skills, good sense, and indomitable work ethic. She is considered plain or ugly; her feet are not bound. Wang Lung sometimes mentions her wide lips. Nevertheless, she is hardworking and self-sacrificing. Towards the end of the book, O-Lan dies due to failing organs. When she lies on her deathbed, Wang Lung pays all of his attention to her and purchases her coffin not long before her death.

- Wang Lung's father – An old, parsimonious senior who seems to only want his tea, food, and grandsons. He desires grandchildren to comfort him in his old age and becomes exceedingly needy and senile as the novel progresses. He has strong and out-dated morals.

Wang Lung and O-Lan's children

- Nung En (Eldest Son) – he is a tall and goodly boy who Wang Lung is very proud of. He grows up as a scholar and goes through a rebellious phase before Wang Lung sends him south for three years to complete his education. He grows up to be a large and handsome man, and he marries the daughter of the local grain merchant, Liu. As his father's position continues to rise, Nung En becomes increasingly enamored with wealth and he wants to live a showy and rich life. He is also the antagonist of the film.

- Nung Wen (Middle Son) – Wang Lung's clever son. He has a shrewd mind for business but he's against his father's traditional ethics. He is described as crafty, thin, and wise with money, and he's far more thrifty than Wang Lung's eldest son. He becomes a merchant and weds a village girl due to thinking women from the town are too vain.

- The Poor Fool – first daughter and third child of O-Lan and Wang Lung, whose mental handicap may have been caused by severe starvation during her infancy. As the years go by, Wang Lung grows very fond of her. She mostly sits in the sun and twists a piece of cloth. By the time of Wang Lung's death, his concubine Pear Blossom (see below) has taken charge of caring for her.

- Second Baby Girl – Killed immediately after delivery.

- Third Daughter – The twin of the youngest son. She is described as a pretty child with an almond flower-colored face and thin red lips. During the story, her feet are bound. She is betrothed to the son of a merchant (her sister-in-law's family) at age 9 and moves to their home at age 13 due to the harassment of Wang Lung's cousin.

- Youngest Son – Put in charge of the fields while the middle and eldest sons go to school. He grows up to be an independent person and runs away to become a soldier, against his father's wishes.

- Eldest Son's Wife – Daughter of a grain merchant and a town woman who hates the middle son's wife due to seeing her as lower class. She is brought to the house before O-Lan's death and is deemed proper and fit by the dying woman. Her first child is a boy.

- Middle Son's Wife – A woman from the village. She hates the first son's wife due to her snobbery and rudeness. Her first child is a girl.

Wang Lung's concubines and servants

- Lotus Flower – Much-spoiled concubine and former prostitute. Eventually becomes old, fat, and less pretty from the tobacco and fattening foods. Helps arrange the eldest son's and youngest daughter's marriages. Loved by Wang Lung.

- Cuckoo – Formerly a slave in the house of Hwang. Becomes madame of the "tea house", eventually becomes a servant to Lotus. Hated by O-Lan because she was cruel to her in the Hwang House.

- Pear Blossom – Bought as a young girl, she serves as a slave to Lotus. At the end of the novel, she becomes Wang Lung's concubine because she says she prefers the quiet devotion of old men to the fiery passions of young men.

- Ching – Wang Lung's faithful friend and neighbour. Shares a few beans with Wang Lung during the famine to save O-Lan's life. After the famine kills Ching's wife and forces him to give his daughter away, Ching sells his land to Wang Lung and comes to work for Wang Lung as his foreman. Dies from an accident in the fields because he was showing a fellow farmer how to thresh grain. Wang Lung has him buried just outside the entrance to the family graveyard, and orders that his own grave should be placed within the perimeter but as close to Ching as possible.

Extended family line

- Wang Lung's Uncle – A sly, lazy man who is secretly one of the leaders of a band of thieves known as the Redbeards. He caused trouble for Wang Lung and others in the household for many years, until eventually, Wang Lung gives him enough opium to keep him in a harmless stupor for the rest of his life. He is described as skinny, gaunt, and very self-defensive. He takes advantage of the tradition that requires younger generations to care for their elders but completely disregards any moral obligation on himself.

- Uncle's Wife – becomes a friend of Lotus; also becomes addicted to opium. Very fat, greedy and lazy.

- Uncle's Son – Wild and lazy, leads Nung En into trouble and eventually leaves to become a soldier. Disrespectful and visits many concubines. Can be described as a sexual predator.

Chronology

The novel is set in a timeless China and provides no explicit dates. There are, however, references to events that provide an approximate time frame, such as introduction of railroads and the 1911 Revolution. Railroads were not constructed until the end of the 19th century, and the train used by Wang Lung and his family is implied to be relatively new, which would place their departure to the South sometime in the early 20th century. Their return after the southern city descends into civil chaos also matches the time of the 1911 Revolution.

Political influence

Some scholars have seen The Good Earth as creating sympathy for China in the oncoming war with Japan. "If China had not captured the American imagination," said one, "it might just have been possible to work out a more satisfactory Far Eastern policy," but such works as The Good Earth, "infused with an understandable compassion for the suffering Chinese, did little to inform Americans about their limited options in Asia."[5] The diplomatic historian Walter LaFeber, however, although he agrees that Americans grew enamored of heroic Chinese portrayed by writers such as Buck, concluded that "these views of China did not shape U.S. policy after 1937. If they had, Americans would have been fighting in Asia long before 1941."[6]

The Columbia University political scientist Andrew J. Nathan praised Hilary Spurling's book Pearl Buck in China: Journey to The Good Earth, saying that it should move readers to rediscover Buck's work as a source of insight into both revolutionary China and the United States' interactions with it. Spurling observes that Buck was the daughter of American missionaries and defends the book against charges that it is simply a collection of racist stereotypes. In her view, Buck delves deeply into the lives of the Chinese poor and opposed "religious fundamentalism, racial prejudice, gender oppression, sexual repression, and discrimination against the disabled."[7]

Peripatetic manuscript

Buck wrote the novel in Nanjing, spending mornings in the attic of her university house to complete the manuscript in one year (ca. 1929).[8] In 1952, the typed manuscript and several other papers belonging to Buck were placed on display at the museum of the American Academy of Arts and Letters in New York. It disappeared after the exhibit, and in a memoir (1966), Buck is said to have written, "The devil has it. I simply cannot remember what I did with that manuscript."[9] After Buck died in 1973, her heirs reported it stolen. It finally turned up at Freeman's Auctioneers & Appraisers in Philadelphia around 2007 when it was brought in for consignment. The FBI were notified and it was handed over by the consignor.[10]

References

- Meyer, Mike (March 5, 2006). "Pearl of the Orient". The New York Times. Retrieved October 10, 2011.

- Canby, Henry Seidel (August 14, 1944). "The 100 Outstanding Books of 1924–1944". Life Magazine. Chosen in collaboration with the magazine's editors.

- "Pearl S. Buck's The Good Earth at a Glance". Oprah.com.

- "Mandarin Transliteration Chart". mandarintools.com.

- O'Neill, William L. (1993). A Democracy At War: America's Fight At Home and Abroad in World War II (1st Harvard University Press paperback ed.). Harvard University Press. p. 57. ISBN 9780674197374. OCLC 43939988. Retrieved September 12, 2020 – via Google Books.

- LaFeber, Walter (1997). The Clash: U.S.-Japanese Relations Throughout History. New York; London: Norton. p. 206. ISBN 9780393318371. OCLC 1166951536.

- "Pearl Buck in China: Journey to The Good Earth". Foreign Affairs. October 27, 2010.

- Conn, Peter J. (1996). Pearl S. Buck: A Cultural Biography. Cambridge, England; New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 345. ISBN 9780521560801. OCLC 1120266149.

- Lester, Patrick (June 28, 2007). "Missing Pearl S. Buck writings turn up four decades later". The Morning Call. Lehigh Valley. Retrieved October 8, 2013.

- "Good Earth Unearthed: Buck's Missing Manuscript Recovered". FBI. June 27, 2007. Retrieved September 9, 2019.

Further reading

- Campbell, W. John (2002). The Book of Great Books: A Guide to 100 World Classics. Barnes & Noble Publishing. pp. 284–294. ISBN 978-0-7607-1061-6. Restricted online copy, p. 284, at Google Books

- Hayford, Charles (1998). "What's So Bad About The Good Earth?" (PDF). Education About Asia. 3 (3).

- Spurling, Hilary (2010). Burying the Bones: Pearl Buck in China. London: Profile. ISBN 978-1-86197-828-8. OCLC 1001576564. Published in the United States as Spurling, Hilary (2010). Pearl Buck in China: Journey to the Good Earth. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4165-4043-4. OCLC 1011612294.

- Roan, Jeanette (2010). "Knowing China: Accuracy, Authenticity and The Good Earth". Envisioning Asia: On Location, Travel, and the Cinematic Geography of U.S. Orientalism. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. pp. 113–55. ISBN 978-0-472-05083-3. OCLC 671655107. Project MUSE copy.

External links

- A Guide to Pearl S. Buck's The Good Earth – Asia for Educators (Columbia University)