The Hole (Scientology)

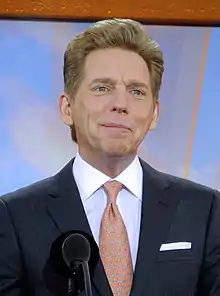

"The Hole" is the unofficial nickname of a facility—also known as the SP Hole, the A to E Room, or the CMO Int trailers—operated by the Church of Scientology on Gold Base, its compound near the town of Hemet in Riverside County, California, United States.[1] Dozens of its senior executives have been confined within the building for months or years. It consists of a set of double-wide trailers within a Scientology compound, joined together to form a suite of offices which were formerly used by the Church's international management team. According to former members of Scientology and media reports, from 2004 the Church's leader David Miscavige sent dozens of senior Scientology executives to the Hole. The Tampa Bay Times described it in a January 2013 article as:

a place of confinement and humiliation where Scientology's management culture—always demanding—grew extreme. Inside, a who's who of Scientology leadership went at each other with brutal tongue lashings, and even hands and fists. They intimidated each other into crawling on their knees and standing in trash cans and confessing to things they hadn't done. They lived in degrading conditions, eating and sleeping in cramped spaces designed for office use.[2]

The executives confined at the Hole are reported to have numbered up to 100 of the most senior figures in Scientology's management, including the Church of Scientology International's President, Heber Jentzsch. Individuals are said to have spent months or even years there. After a few managed to escape the Hole and Scientology, they gave accounts of their experiences to the media, the courts and the FBI, leading to widespread publicity about the harsh conditions that they had allegedly endured. The Church of Scientology has denied those accounts. It says that "the Hole does not exist and never has" and states that nobody had been held against their will.[2] However, it acknowledges that its members are subjected to "religious discipline, a program of ethics and correction entered into voluntarily as part of their religious observances."[3]

Background

The facility known as the Hole is located on the Church of Scientology's Gold Base, built on the site of a resort called Gilman Hot Springs in the California town of San Jacinto. The base covers 520 acres (210 ha) bisected by a public highway, Gilman Springs Road, just off California State Route 79. It was secretly acquired by Scientology in 1978[4] under the alias of the "Scottish Highland Quietude Club".[5] Scientology established a secret base there which was staffed by members of the Sea Org, an inner core of Scientologists which is said to number some five to seven thousand people.[6] There are now two Sea Org bases in the compound: Gold, which houses the Church's in-house film studio Golden Era Productions, and Int, the Church's international headquarters, though in practice the whole site is usually called Gold Base.[5]

Members of the Sea Org are subject to a rigid code of discipline known as "Scientology Ethics" which is enforced by Ethics Officers. Scientologists are encouraged to look out for any fellow members violating Ethics and to submit "Knowledge Reports" on any violations they spot.[7] If Ethics are violated, a "trial" by a Committee of Evidence can lead to punishments administered by a body called the Rehabilitation Project Force (RPF). Such punishments, which can last for months or years, typically consist of a regime of physical labor and lengthy daily confessions of "evil purposes".[8] Such assignments can also be received for performing work poorly, showing negative personality indicators (doubts, hostility etc.) or causing trouble.[9] Individuals assigned in this way are kept isolated and prohibited from having contact with other members of Scientology and the public.[10]

According to Marc and Claire Headley, two Scientologists who left the Church in 2005, residents at the base are not permitted to leave without the permission of a supervisor and have to work at least sixteen hours a day, from 8 am to past midnight, with shorter hours on Sundays and little time for socialising. Communications with the outside world are effectively cut off; cellphones and Internet access are generally banned, mail is censored and passports are kept in a locked filing cabinet. The perimeter of the base is closely guarded around the clock. It is ringed with high fences that are topped with spikes and razor wire and monitored by inward-facing motion sensors to detect anyone trying to climb out of the compound. The Tampa Bay Times reported that dozens of workers tried to escape from the base—some of them repeatedly—but were caught and returned by Sea Org "pursuit teams". The escapees are said to have been subjected to isolation, interrogation and punishment on their return to the compound.[11]

Origin

Defectors from Scientology say that from around 2002, Church leader David Miscavige began to publicly slap, kick, punch or shove executives at the base who had angered him.[12] John Brousseau, the estate manager at Gold Base and a veteran Sea Org member, said that Miscavige repeatedly faulted his subordinates' work, "constantly berating them, nitpicking everything they're doing, pointing out inadequacies, ineffectiveness, lack of results, blaming it all on them and their inability to do anything right, and on the other hand saying how he's got to do everything himself—he's the only one who can do anything right."[13] High-level meetings became tense affairs punctuated by "profane, belittling rants".[2] According to emails said to have come from Miscavige's "Communicator"—the personal assistant responsible for passing on transcribed messages from the leader—he routinely berated subordinates with terms such as "CSMF" (meaning "Cock-sucking motherfucker")[14] and "YSCOHB" (meaning "You suck cock on Hollywood Boulevard").[15]

A practice called "overboarding" was reintroduced as a further method of enforcing discipline on the base. It had been devised during the 1960s when Scientology's founder, L. Ron Hubbard, was living aboard a former Irish Sea cattle ferry Royal Scotman [sic] (later Apollo), in which he roamed the Mediterranean at the head of a small fleet of ships crewed by Sea Org members. In response to perceived violations, Scientologists were thrown over the side of the ship; sometimes they were bound and blindfolded before being tossed overboard.[16] Scientology spokesmen describe the practice as "a Sea Org ritual akin to traditions in other religious orders" and "part of ecclesiastical justice".[17]

Some Scientology churches (or "orgs") adopted a land-based version of overboarding by making staff members stand against a wall while other Scientologists threw buckets of water at them, but the practice was largely abandoned in the 1970s.[18] According to author Janet Reitman, Miscavige reintroduced it in the 2000s and ordered dozens of senior executives to go outdoors in the middle of the night and assemble at the base's swimming pool or its muddy lake. They would then jump or be pushed into the water, often in freezing conditions, while fully clothed and with Miscavige watching.[19] Scientology acknowledges that overboarding took place but characterises it as part of its "ecclesiastical justice" system for dealing with poor performance.[17]

According to Reitman, in the late fall of 2004 Miscavige called together 70 senior Scientology executives in a pair of double-wide trailers normally used as the international management team's offices. They were ordered to play a game of musical chairs in the management conference room. Those who failed to get a chair when the music stopped would be "offloaded" from the base, away from their spouses and children, to languish in the most remote and unpleasant locations in Scientology's empire. As Queen's Greatest Hits was played, the competition for seats became increasingly fierce: "By the time the number had dwindled to twenty, people were throwing one another against the walls, ripping seats from one another's hands, wrestling one another to the floor."[20] At the end of the contest, Miscavige ordered that all the executives were to stay in the conference room and sleep under the tables until further notice. They stayed there for the next few days, with occasional deliveries of food, before being released.[20] Scientology's then chief spokesman, Tommy Davis, has acknowledged that the "musical chairs" incident occurred and says that it was "intended to demonstrate how disruptive wholesale changes could be on an organization" but dismisses the accounts of threats and violence.[21]

Later in 2004, according to Reitman, a purge was carried out of staff at the base. Hundreds were sent to the RPF while dozens of others were offloaded and expelled from the Sea Org with huge "freeloader bills" presented to them for Scientology services they had received over the years.[22] Dozens of senior executives were accused of being "suppressive persons". They were said to have been confined in the management team offices and ordered to carry out the "A to E steps", a set of penances intended to demonstrate that they had repented of their "crimes" and reformed. In particular, they were to confess and identify which of them were "defying [Miscavige] and sabotaging Scientology with their incompetence".[2] The management offices, which had formerly been referred to as "the CMO Int trailer", became known as the "A to E Room," the "SP Hole", and ultimately simply "the Hole".[23]

Life in the Hole

From 2004 to 2007, the number of people confined in the Hole increased from 40 to up to 100. They slept in cots or sleeping bags, squeezed into every available floor space or on desktops. Men would sleep around the conference table while women slept in cubicles and small offices around the main conference room. They were so crowded that there was barely any room to move, according to one of those present: "Everyone sleeping with only about six inches on either side. Above you. Below you. Getting up in the middle of the night, you'd disturb everyone."[24] They were only allowed to leave to attend Scientology events or to be taken to a shower in a nearby maintenance garage, to which they were taken two at a time under guard. Food was brought to them on golf carts from the Gold Base mess hall, as the executives were not allowed to eat with the rest of the staff, and they were only given ten to fifteen minutes to eat.[2][17] According to one of the executives, the food was "like leftovers, slop, bits of meat, soupy kind of leftovers thrown into a pot and cooked and barely edible."[3] The building was said to be infested with ants and on several occasions the electricity was turned off, causing the temperature inside to reach 106 °F (41 °C) due to the lack of air conditioning.[3]

Brousseau commented that when he visited the Hole occasionally, "you could smell that people live here, people sleep here."[13] He saw the executives being marched elsewhere on the base to take showers; his impression was that "they looked like they were being marched to the gallows—they just looked lifeless, with no purpose. Very hang-dog, droopy shoulders, slouchy, very sad, inward-looking creatures."[13] Brousseau said that they were only allowed out "at certain times of day that would be adjudicated to be the least likely time when DM [Miscavige] would run into them if he was on the property. They would march out to Old Gilman House to take a shower and come back because they had no shower facilities inside the Hole. Later that got upgraded to let them go down to the garage."[25] Sometimes executives were allowed out for a short time to attend Scientology events, but many ended up spending months or even years in the Hole.[2]

The individuals who were later named by the media as being held in the Hole represented a who's who of Scientology's top management. They included Debbie Cook, the head of the Church of Scientology Flag Service Organization; Heber Jentzsch, the President of the Church of Scientology International; Guillaume Lesevre, the Executive Director International and the church's top management official; Mark Rathbun, the Inspector General of the Religious Technology Center; Wendell Reynolds, the International Finance Director; Mike Rinder, the Commanding Officer of the Office of Special Affairs; Kurt Weiland, director of external affairs for the Office of Special Affairs; Marc Yager, the Commanding Officer of the Commodore's Messenger Organization; and Norman Starkey, the former captain of Hubbard's ship, the Apollo.[2][23]

Executives who eventually escaped from the Hole have said that its occupants were forced to practice group confessions in which they would confess supposed transgressions against Miscavige, bad thoughts that they had had about Scientology and disclose their sexual fantasies.[17] Cook, who spent seven weeks in the Hole in 2007, said that "most of the time the activities [in the Hole] were either you confessing your own sins or bad things that you'd done, or getting other people to confess theirs."[3] Rinder commented on the bizarre personal dynamics of the Hole: "These were your friends, people you had traveled with. But then, you get in the Hole? You can't trust anybody."[24]

Rinder told the Tampa Bay Times that interrogations "would be carried out by whoever happened to be there—twenty people, thirty people, fifty people, all standing up and screaming at you, and ultimately it sort of devolved into physical violence, torture, to extricate these 'confessions' out of people."[13] According to Rinder, the confessions were sometimes dictated by Miscavige, but more usually the inmates of the Hole would force each other to confess: "The fifty people there are all screaming at me, telling me I've got to confess—I've done that, why don't I just admit it? I stole money, I had affairs—people would just literally dream up bullshit and start screaming it out, and then the mob goes crazy: 'Oh yeah, it must have been that!'"[13] Tom De Vocht, who was also in the Hole, recalled that "everybody in that damned room—people are wild and out of control, I punched somebody. Everybody was punched. And screaming and yelling. It just got like, 'What the hell is going on here?'"[17] De Vocht rationalized his own involvement on the grounds of self-defense: "If I don't attack I'm going to be attacked. It's a survival instinct in a weird situation that no one should be in."[26]

The pressure evidently worked, as Rinder wrote an "Apology and Announcement" on June 4, 2005 in which he told Miscavige, "I recognise very clearly how Treasonous I have been towards you and Scientology."[13] He subsequently commented that such written confessions "read like North Korean POW writeups",[13] alluding to the way that Korean War POWs detained in North Korea were forced to go through brainwashing to renounce their "reactionary imperialist" mindset. He explained to the Tampa Bay Times why people did not simply walk out of the Hole: "If you leave you are going to lose contact with your family and any friends who are Scientologists. You have it pounded into you the whole time that the only reason someone leaves a group like that is because they are bad, that you have done something that force you to have to leave."[27] He noted people had invested a great deal of themselves in Scientology, that Sea Org members have "made a commitment beyond even a single lifetime" and that the prevailing attitude was that, "'I've lived through many lifetimes and there are lots of experiences that I've had that are far worse than this, so I can put up with this and I can stand it'."[27]

What was happening in the Hole took place out of view of the other staff members at Gold Base, but it was clear that it would not be a good thing to be sent there. According to author Lawrence Wright, "the entire base became paralyzed with anxiety about being thrown into the Hole. People were desperately trying to police their thoughts, but it was difficult to keep secrets when staff members were constantly being security-checked with E-Meters." Wright reports that Miscavige's statements were transcribed for the executives in the Hole, who would then have to repeatedly read them out loud to each other.[28]

Former Scientology members have said that conditions in the Hole worsened in 2006 after several executives had escaped. Security was tightened to prevent the confined executives from "blowing" (leaving). Brousseau says that he was ordered to fasten steel bars across the doors of the building, and the windows were modified so that they could only be opened a few inches. Another staff member objected, pointing out that any outsider could see the bars. They were removed after a few weeks, but the building was guarded around the clock to prevent further escapes.[2] The Church of Scientology denies that bars were ever installed, saying, "Any allegation of bars being installed to hold people against their will is false and malicious and is denied."[29]

From 2006, according to Rinder, executives undergoing "group confessions" were made to stand in big trash cans in the middle of the floor with signs around their necks on which various derogatory statements were written. Rinder described how it became "relatively routine" for people to be "slapped, punched, kicked, pushed, shoved, thrown up against the wall" in order to make them confess.[13] He told the Tampa Bay Times that he and other people were made to crawl continuously on rough carpeting around a conference room table with their trouser legs rolled up, getting kicked from behind if they stopped, which resulted in them suffering severely contused and abraded knees after days of such treatment.[2] There was an escalation in the level of confessions demanded, such that they became "more and more dramatic and over the top in order to be acceptable".[13] He described how Weiland was made to sit under an air vent with the cooling system turned up high, while cold water was poured over his head. After an hour or so, he was "shaking so uncontrollably and his lips were so completely blue that he was incapable of talking".[13] (Weiland denied to the Times that this incident had ever happened.)[2]

Cook testified in a San Antonio court in 2012 that she had been on the phone to Miscavige when two Scientologists crawled in through her office window and seized her, conveying her to the Hole.[30] She said that she had subsequently been "put in a trash can, [had] cold water poured over [her], [and] slapped".[3] According to Rathbun, who had left Scientology by this time, for twelve hours "Debbie was made to stand in a large garbage can and face one hundred people screaming at her demanding a confession as to her 'homosexual tendencies'. While this was going on, water was poured over her head. Signs were put around Debbie's neck, one marked in magic marker 'LESBO' while this torture proceeded. Debbie was repeatedly slapped across the face by other women in the room during the interrogation. Debbie never did break."[31]

Cook told the court that another Scientology executive, who had not been sent to the Hole, had objected to what he had seen there on a visit. According to Cook, the executive was given a two-hour beating and ordered to lick a bathroom floor for at least thirty minutes.[30] She testified that Yager and Lesevre, two of Scientology's most senior executives, were pressured to state that they had had a homosexual affair and were beaten until they "confessed".[23] According to De Vocht, Miscavige pushed Yager to the ground and told a black executive, "By the way, [Yager] thinks black people are niggers, and he doesn't want Scientology to help blacks. Go kick him.' So [Yager] is down on the ground and she's kicking him." Both Yager and the other executive have denied this account.[17]

Leaving the Hole

Rathbun spent only four days in the Hole in 2004 but says that he left after seeing his old friend, De Vocht, being physically beaten by Miscavige. According to Rathbun, one night the incarcerated executives were ordered to jog to a building 400 yards away and back. As they were herded back to the Hole, he broke away and hid in bushes until the group had disappeared from sight. He retrieved his motorcycle, hid in the brush and drove out through the Gold Base gates when they were opened to let a car in.[17] He subsequently rented a car and spent a month touring the South before settling in southern Texas.[32]

De Vocht left Scientology in May 2005 after he was allegedly attacked by Miscavige. According to De Vocht, he told his wife—a Miscavige aide—that he would fight back if it happened again. He was subsequently declared to be a "suppressive person" and announced his intention to leave. The compound's guard refused to open the gate, so he climbed the fence and walked to Hemet, six miles away. He was later sent a $98,000 "freeloader bill" by the Church.[32]

Rinder spent almost two years in the Hole between 2004 and 2007, leaving it occasionally to deal with public relations matters such as dealing with the BBC journalist John Sweeney's documentary Scientology and Me. Rinder says that Miscavige was furious with the way that Sweeney had been handled and ordered Rinder to go to Sussex to dig ditches on a Scientology property there. He defected instead, eventually settling in Denver, Colorado.[32]

Cook left the Hole in May 2007 after spending seven weeks there, when she was sent back to Clearwater, Florida to organize a major public event involving Miscavige. According to Cook, she was driven to downtown Clearwater by another staff member, along with her husband, to eat at Scientology's dining hall. The couple took the opportunity to flee when the staff member went inside to get breakfast; Cook jumped into the driver's seat, drove with her husband to the nearest car rental outlet and hired a car to drive up to her father's house in North Carolina. Before they got there, they were intercepted by Scientology officials and ordered to return to Clearwater. She spent three weeks under guard, at one point writing in a letter to her mother that if she was not released she "would take whatever steps necessary, like slitting my wrists" before finally signing a severance agreement. She later said that by that point, "I would have signed that I stabbed babies over and over again and loved it".[30]

Brousseau was not sent to the Hole, but what he saw of it made him decide to leave Scientology in 2010 after 33 years in the Church. He was struck by how "dozens of these people [in the Hole], they were just so alive, but I looked at them now and they were just husks. They wouldn't say or originate anything, they seemed to have no purpose, they were just like sheep. There's no way 100 people could be evil horrid [suppressive persons] and DM's the only [ethical] one. No way."[13] He had known and been friends with some of those in the Hole for decades and could not bear what he was seeing. As he put it, "I can't stop it, but I can at least stop supporting it. So I left."[2] He left a note in his room for his colleagues to find: "By now you've noticed I'm gone. I couldn't stand to see my Sea Org friends so mistreated. I won't support it anymore. Goodbye."[11]

Media exposure and legal inquiries

From 2009, several former Scientology executives began to speak out about the Hole, both to the media and to the FBI. Rathbun wrote in the New York Daily News in July 2012 that he had "decided that [he] had to speak out before someone was killed in the Hole".[33] In June 2009, the Tampa Bay Times published a series of articles on the internal workings of Scientology titled "The Truth Rundown", detailing accounts of beatings and other episodes of violence between Miscavige and other top Scientology executives.[26] The Times followed up in January 2013 with a detailed account of the Hole, supplemented by interviews with defectors from Scientology,[2] while The Village Voice sought to compile a list of the executives said to have been incarcerated there.[23] ABC News also reported on Cook's account of the Hole.[3]

According to Brousseau, the bad publicity led to reforms of the Hole. Its inmates were allowed to sleep in proper beds in the "Berthing" quarters elsewhere in the compound. He describes their new seven-days-a-week routine starting when "they got up, showered, then went to the dining hall at 9:30. They had thirty minutes for breakfast. Then they walked up to the Hole. They sat down at desks. I have no clue what work they did. They worked until 12:30 or 1 pm. Then they were marched back to the dining hall and had thirty minutes for lunch. Then they were marched back to the Hole and were there until 6 pm."[23] After a thirty-minute dinner, they were taken to the study hall and stayed there "for two and a half hours, until about 9:30. Then they went to the Hole again to wrap up their day. At 11 or midnight, they'd get marched back to Berthing."[23] Some of the restrictions on contacting people outside the Hole were also said to have been eased. However, other Scientology staff were still encouraged to avoid contact with the inmates: "You didn't talk to them, you looked the other way, you'd leave the area if you saw them, it's like the black plague."[25] Brousseau commented: "You stayed away from these people. They're considered the worst of the worst."[23]

Attempts by law enforcement to investigate conditions at Gold Base have been blocked by legal difficulties and the unwillingness of those on the base to talk to police. According to Wright, who wrote an account of the Hole in his 2013 book Going Clear: Scientology, Hollywood, and the Prison of Belief, the Riverside County sheriff's office has never received a complaint from someone at the base about their treatment there, despite the many accounts of mistreatment. Wright attributes this to the fear that many Scientologists have of bringing shame upon Scientology and of being forced to break off contact with their families and friends.[34]

In 2009, the FBI opened an investigation into potential human trafficking offences by the Church of Scientology, after the accounts of defectors from Gold Base were published. The Tampa Bay Times reported that FBI aerial surveillance of the property showed columns of executives being escorted to and from the Hole. However, no action was taken against Scientology. The investigation ground to a halt after a ruling by a U.S. District Court judge in a case concerning Marc and Claire Headley's complaints against Scientology over their treatment at Gold Base.[35]

Headley et al. v. Church of Scientology International et al.

In 2009, Marc and Claire Headley sued Scientology under the federal Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000.[36] In response, Scientology lawyers argued that the First Amendment prohibited the courts from considering "a forced labor claim premised upon ... social and psychological factors", because they concern "the beliefs, the religious upbringing, the religious training, the religious practices, the religious lifestyle restraints of a religious order".[35]

Scientology acknowledged that the rules under which the Headleys lived included a ban on having children, censored mail, monitored phone calls, needing permission to have Internet access and being disciplined through manual labor. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals noted in a ruling given in July 2012 that Marc Headley had been made to clean human excrement by hand from an aeration pond on the compound with no protective equipment, while Claire Headley was banned from the dining hall for up to eight months in 2002. She lost 30 pounds (14 kg) as a result of subsisting on protein bars and water. In addition, she was coerced into having two abortions to comply with the Sea Org's no-children policy. The Headleys also experienced physical abuse from Scientology executives and saw others being treated violently.[36]

However, the court found that Scientology enjoyed the protection of the free exercise of religion clause in the First Amendment, and that it could use the "ministerial exemptions" in employment law to deflect litigation over its treatment of its members. The judge ruled that the First Amendment disallowed the courts from "examining church operations rooted in religious scripture". Bringing Scientology to account for how it disciplined its members was "precisely the type of entanglement that the religion clauses prohibit". However, the Ninth Circuit did suggest that other types of claims would withstand appellate review, such as assault, battery or "any of a number of other theories that might have better fit the evidence".[37] The ruling has effectively meant that it is impossible to bring charges against Scientology based on claims of "trafficking in persons". As one attorney has put it, "Here is a court saying, albeit in a civil situation ... that there is nothing improper with this type of conduct and no ill motive can be imbued to the church."[35] Former U.S. federal prosecutor Michael Seigel says that the ruling "doesn't seem to leave much room for hope of success on a criminal prosecution". The FBI investigation was dropped in 2011.[35]

Church of Scientology International v. Debbie Cook

In January, 2012, Scientology brought a lawsuit against Cook for defamation after she sent an e-mail to 3,000 Church members criticizing its fundraising methods.[38][39] The lawsuit against her was quickly settled without payment by any side on April 23, 2012 after Cook was permitted to testify for three hours regarding her description of conditions at the Hole.[40]

References

- Wright, Lawrence (February 14, 2011). "The Apostate: Paul Haggis v. The Church of Scientology" Archived 2013-03-02 at the Wayback Machine. The New Yorker (Tampa Bay Times). Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- Tobin, Thomas C; Childs, Joe (January 13, 2013). "Scientology defectors describe violence, humiliation in "the Hole"". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on February 7, 2019.

- Harris, Dan (February 29, 2012). "Another PR Crisis for Scientology". ABC News.

- Atack 1990, p. 256

- Wright 2013, p. 175

- Bromley 2009, p. 99

- Atack 1990, p. 156

- Kent 2001a, p. 112

- Kent 2001b, p. 354

- Kent 2001b, p. 361

- Childs, Joe; Tobin, Thomas C. (January 13, 2013). "FBI's Scientology investigation: Balancing the First Amendment with charges of abuse and forced labor". Tampa Bay Times.

- Reitman 2011, p. 333

- Childs, Joe; Tobin, Thomas C. (January 13, 2013). "Ex-Scientologists Describe "The Hole"". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on January 14, 2012.

- Sweeney 2013, p. 155

- Sweeney 2013, p. 232

- Atack 1990, p. 186

- Tobin, Thomas C; Childs, Joe (June 23, 2009). "Scientology: Ecclesiastical justice". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on May 8, 2013. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- Reitman 2011, p. 93

- Reitman 2011, p. 326

- Reitman 2011, p. 339

- Wright 2013, p. 363

- Reitman 2011, p. 340

- Ortega, Tony (August 2, 2012). "Scientology's Concentration Camp for Its Executives: The Prisoners, Past and Present". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on April 7, 2015.

- Ortega, Tony (April 4, 2012). "Mike Rinder on "the Hole," Indoctrination, Confessions, and His Ultimate Escape". The Village Voice.

- Tobin, Thomas C; Childs, Joe; Rivenbark, Maurice (January 13, 2013). "Suppressed: John Brousseau—Outcasts". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on January 14, 2012.

- Tobin, Thomas C; Childs, Joe (June 21, 2009). "Scientology: The Truth Rundown". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on February 28, 2013.

- Tobin, Thomas C; Childs, Joe; Rivenbark, Maurice (January 13, 2013). "Suppressed: Mike Rinder—Why they stay". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on January 14, 2012.

- Wright 2013, p. 280

- Pouw, Karin (June 24, 2012). "Church of Scientology responds to Times series about FBI investigation". Tampa Bay Times.

- Tobin, Thomas C; Childs, Joe (February 10, 2012). "Ex-Clearwater Scientology officer Debbie Cook testifies she was put in 'the Hole', abused for weeks". Tampa Bay Times.

- Ortega, Tony (January 4, 2012). "Scientology in Crisis: Debbie Cook's Transformation from Enforcer to Whistleblower". Village Voice.

- Tobin, Thomas C; Childs, Joe (February 10, 2012). "Leaving the Church of Scientology: a huge step". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on June 7, 2013. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- Rathbun, Mark (July 2, 2012). "Former Church of Scientology inspector general Marty Rathbun explains how he escaped a destructive cult and what Katie Holmes is up against". New York Daily News.

- Strayton, Jennifer (January 28, 2013). "Listen: Austin Author Lawrence Wright on 'Going Clear,' His Controversial Book on Scientology". KUT News.

- Childs, Joe; Tobin, Thomas C. (January 14, 2013). "FBI Scientology investigation gets a fresh witness, but hits a legal roadblock". Tampa Bay Times.

- De Atley, Richard K. (July 24, 2012). "CHURCH OF SCIENTOLOGY: Two former ministers' lawsuit loses on appeal". Riverside Press-Enterprise. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- "Marc And Claire Headley Lose Forced Labor Lawsuit Against Church Of Scientology". Associated Press. July 24, 2012. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- Ortega, Tony (February 9, 2012). "Scientology, Deep in the Heart of Texas: The Voice at the Debbie Cook Hearing". Village Voice. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- "Scientology defectors describe violence, humiliation in 'the Hole'" Archived 2013-03-02 at the Wayback Machine. Tampa Bay Times. January 12, 2013. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- "Ex-Scientology Leader Moving to Caribbean Island" Archived 2013-03-02 at the Wayback Machine. Tampa Bay Times. June 19, 2012. Retrieved February. 22, 2013.

Bibliography

- Atack, Jon (1990). A Piece of Blue Sky: Scientology, Dianetics, and L. Ron Hubbard Exposed. Carol Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8184-0499-3.

- Bromley, David G. (2009). "Making Sense of Scientology: Prophetic, Contractual Religion". In Lewis, James R (ed.). Scientology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533149-3.

- Kent, Stephen A (2001a). From Slogans to Mantras: Social Protest and Religious Conversion in the Late Vietnam War Era. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-2948-1.

- Kent, Stephen A. (2001b). "Brainwashing Programs in The Family/Children of God and Scientology". In Robbins, Thomas; Zablocki, Benjamin David (eds.). Misunderstanding Cults: Searching for Objectivity in a Controversial Field. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-8188-9.

- Melton, J. Gordon (2011). Religious Celebrations: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations. ABC-CLIO.

- Reitman, Janet (2011). Inside Scientology: The Story of America's Most Secretive Religion. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-618-88302-8.

- Sweeney, John (2013). The Church of Fear: Inside the Weird World of Scientology. Silvertail Books. ISBN 978-1-909269-03-3.

- Wright, Lawrence (2013). Going Clear: Scientology, Hollywood, and the Prison of Belief. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-385-35027-3.