Politics (Aristotle)

Politics (Greek: Πολιτικά, Politiká) is a work of political philosophy by Aristotle, a 4th-century BC Greek philosopher.

| Part of a series on the |

| Corpus Aristotelicum |

|---|

|

| Logic (Organon) |

|

| Natural philosophy (physics) |

|

| Metaphysics |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Other links |

|

|

[*]: Generally agreed to be spurious [†]: Authenticity disputed |

The end of the Nicomachean Ethics declared that the inquiry into ethics necessarily follows into politics, and the two works are frequently considered to be parts of a larger treatise—or perhaps connected lectures—dealing with the "philosophy of human affairs".

The title of Politics literally means "the things concerning the πόλις : polis", and is the origin of the modern English word politics.

Overview

Structure

Aristotle's Politics is divided into eight books, which are each further divided into chapters. Citations of this work, as with the rest of the works of Aristotle, are often made by referring to the Bekker section numbers. Politics spans the Bekker sections 1252a to 1342b.

Book I

In the first book, Aristotle discusses the city (πόλις : polis) or "political community" (κοινωνία πολιτική : koinōnía politikē) as opposed to other types of communities and partnerships such as the household (οἶκος : oikos) and village.

The highest form of community is the polis. Aristotle comes to this conclusion because he believes the public life is far more virtuous than the private and because men are "political animals".[1] He begins with the relationship between the city and man (I. 1–2), and then specifically discusses the household (οἶκος : oikos) (I. 3–13).[2]

He takes issue with the view that political rule, kingly rule, rule over slaves and rule over a household or village are only different in size. He then examines in what way the city may be said to be natural.

Aristotle discusses the parts of the household (οἶκος : oikos), which includes slaves, leading to a discussion of whether slavery can ever be just and better for the person enslaved or is always unjust and bad. He distinguishes between those who are slaves because the law says they are and those who are slaves by nature, saying the inquiry hinges on whether there are any such natural slaves.

Only someone as different from other people as the body is from the soul or beasts are from human beings would be a slave by nature, Aristotle concludes, all others being slaves solely by law or convention. Some scholars have therefore concluded that the qualifications for natural slavery preclude the existence of such a being.[3]

Aristotle then moves to the question of property in general, arguing that the acquisition of property does not form a part of household management (οἰκονομική : oikonomikē) and criticizing those who take it too seriously. It is necessary, but that does not make it a part of household management any more than it makes medicine a part of household management just because health is necessary.

He criticizes income based upon trade and upon interest, saying that those who become avaricious do so because they forget that money merely symbolizes wealth without being wealth and "contrary to nature" on interest because it increases by itself not through exchange.

Book I concludes with Aristotle's assertion that the proper object of household rule is the virtuous character of one's wife and children, not the management of slaves or the acquisition of property. Rule over the slaves is despotic, rule over children kingly, and rule over one's wife political (except there is no rotation in office). Aristotle questions whether it is sensible to speak of the "virtue" of a slave and whether the "virtues" of a wife and children are the same as those of a man before saying that because the city must be concerned that its women and children be virtuous, the virtues that the father should instill are dependent upon the regime and so the discussion must turn to what has been said about the best regime.

Book II

Book II examines various views concerning the best regime.[2] It opens with an analysis of the regime presented in Plato's Republic (2. 1–5), holding that communal share of property between the guardians will increase rather than decrease dissensions, and sharing of wives and children will destroy natural affection. He concludes that common sense is against this arrangement for good reason, and claims that experiment shows it to be impractical. Next, an analysis of the regime presented in Plato's Laws (2. 6). Aristotle then discusses the systems presented by two other philosophers, Phaleas of Chalcedon (2. 7) and Hippodamus of Miletus (2. 8).

After addressing regimes invented by theorists, Aristotle moves to the examination of three regimes that are commonly held to be well managed. These are the Spartan (2. 9), Cretan (2. 10), and Carthaginian (2. 11). The book concludes with some observations on regimes and legislators.

Book III

- Who can be a citizen?

"He who has the power to take part in the deliberative or judicial administration of any state is said by us to be a citizen of that state; and speaking generally, a state is a body of citizens sufficing for the purpose of life. But in practice a citizen is defined to be one of whom both the parents are citizens; others insist on going further back; say two or three or more grandparents." Aristotle asserts that a citizen is anyone who can take part in the governmental process. He finds that most people in the polis are capable of being citizens. This is contrary to the Platonist view, asserting that only very few can take part in the deliberative or judicial administration of the state.[1]

- Classification of constitution and common good.

- Just distribution of political power.

- Types of monarchies:

- Monarchy: exercised over voluntary subjects, but limited to certain functions; the king was a general and a judge, and had control of religion.

- Absolute: government of one for the absolute good

- Barbarian: legal and hereditary + willing subjects

- Dictator: installed by foreign power elective dictatorship + willing subjects (elective tyranny)

Book IV

- Tasks of political theory

- Why are there many types of constitutions?

- Types of democracies

- Types of oligarchies

- Polity (Constitutional Government) – highest form of government

- When perverted, a Polity becomes a Democracy, the least harmful derivative government as regarded by Aristotle.

- Government offices

Book V

- Constitutional change

- Revolutions in different types of constitutions and ways to preserve constitutions

- Instability of tyrannies

Book VI

- Democratic constitutions

- Oligarchic constitutions

Book VII

- What is Eudaimonia, welfare for the individual? Restate conclusions of Nicomachean Ethics

- Best life and best state.

- Ideal state: its population, territory, and position

- Citizens of the ideal state

- Marriage and children

Book VIII

- Paideia, education in the ideal state

- Music Theory. For didactics, Dorian mode is preferred for its manly qualities, over Phrygian mode and Ionian mode

Classification of constitutions

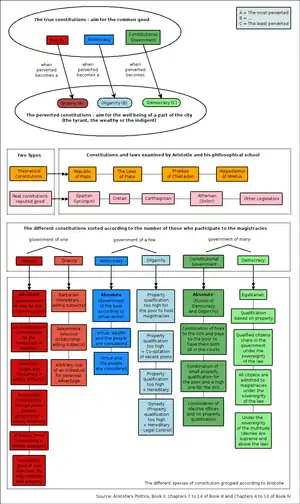

After studying a number of real and theoretical city-states' constitutions, Aristotle classified them according to various criteria. On one side stand the true (or good) constitutions, which are considered such because they aim for the common good, and on the other side the perverted (or deviant) ones, considered such because they aim for the well being of only a part of the city. The constitutions are then sorted according to the "number" of those who participate to the magistracies: one, a few, or many. Aristotle's sixfold classification is slightly different from the one found in The Statesman by Plato. The diagram above illustrates Aristotle's classification. Moreover, following Plato's vague ideas, he developed a coherent theory of integrating various forms of power into a so-called mixed state:

It is … constitutional to take … from oligarchy that offices are to be elected, and from democracy that this is not to be on a property-qualification. This then is the mode of the mixture; and the mark of a good mixture of democracy and oligarchy is when it is possible to speak of the same constitution as a democracy and as an oligarchy.

— Aristotle. Politics, Book 4, 1294b.10–18

To illustrate this approach, Aristotle proposed a first-of-its-kind mathematical model of voting, albeit textually described, where the democratic principle of "one voter–one vote" is combined with the oligarchic "merit-weighted voting"; for relevant quotes and their translation into mathematical formulas see (Tangian 2020).[4]

Composition

The literary character of the Politics is subject to some dispute, growing out of the textual difficulties that attended the loss of Aristotle's works. Book III ends with a sentence that is repeated almost verbatim at the start of Book VII, while the intervening Books IV–VI seem to have different flavor from the rest; Book IV seems to refer several times back to the discussion of the best regime contained in Books VII–VIII.[5] Some editors have therefore inserted Books VII–VIII after Book III. At the same time, however, references to the "discourses on politics" that occur in the Nicomachean Ethics suggest that the treatise as a whole ought to conclude with the discussion of education that occurs in Book VIII of the Politics, although it is not certain that Aristotle is referring to the Politics here.[6]

Werner Jaeger suggested that the Politics actually represents the conflation of two, distinct treatises.[7] The first (Books I–III, VII–VIII) would represent a less mature work from when Aristotle had not yet fully broken from Plato, and consequently show a greater emphasis on the best regime. The second (Books IV–VI) would be more empirically minded, and thus belong to a later stage of development.

Carnes Lord, a scholar on Aristotle, has argued against the sufficiency of this view, however, noting the numerous cross-references between Jaeger's supposedly separate works and questioning the difference in tone that Jaeger saw between them. For example, Book IV explicitly notes the utility of examining actual regimes (Jaeger's "empirical" focus) in determining the best regime (Jaeger's "Platonic" focus). Instead, Lord suggests that the Politics is indeed a finished treatise, and that Books VII and VIII do belong in between Books III and IV; he attributes their current ordering to a merely mechanical transcription error.[8]

It is uncertain whether Politics was translated into Arabic like most of his major works.[9] Its influence and ideas were, however, carried over to Arabic philosophers.[10]

Translations

- Barker, Sir Ernest (1995). The Politics of Aristotle. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-953873-7.

- Jowett, Benjamin (1984). Jonathan Barnes (ed.). Politics. The Complete Works of Aristotle. Vol. 2. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-01651-1.

- Lord, Carnes (2013). Aristotle's Politics: Second Edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-92183-9.

- Lord, Carnes (1984). The Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-02669-5. (Out of Print)

- Reeve, C. D. C. (1998). Politics. Indianapolis: Hackett. ISBN 978-0-87220-388-4.

- Sachs, Joe (2012). Politics. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Focus. ISBN 978-1585103768.

- Simpson, Peter L. P. (1997). The Politics of Aristotle: Translation, Analysis, and Notes. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-2327-9.

- Sinclair, T. A. (1981). The Politics. Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-044421-6.

See also

- Kyklos, the cycle of governments in a society

- Plato's five regimes

Notes

- Ebenstein, Alan (2002). Introduction to Political Thinkers. Boston, MA: Wadsworth.

- Lord (1982), "Introduction," 27.

- Nichols, Mary (1992). Citizens and Statesmen. Maryland: Rowman and Little field Publishers, Inc.

- Tangian 2020, pp. 35–38.

- Lord (1982), "Introduction," 15.

- Lord (1982), "Introduction," 19, 246 n. 53.

- Werner Jaeger, Aristoteles: Grundlegung einer Geschichte seiner Entwicklung (1923).

- Lord (1982), "Introduction," 15–16

- Pinès (1986), 47, 56

- Pinès (1986), 56

Works cited

- Lord, Carnes (1982). Education and Culture in the Political Thought of Aristotle. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Pinès, Shlomo (1986). "Aristotle's Politics in Arabic Philosophy". Collected works of Shlomo Pines: Studies in Arabic Versions of Greek texts and in Medieval Science. Vol. 2. Jerusalem: The Magnes Press. pp. 146–156. ISBN 965-223-626-8.

- Tangian, Andranik (2020). Analytical theory of democracy. Vol. 1. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-39691-6. ISBN 978-3-030-39690-9.

Further reading

- Aquinas, St. Thomas (2007). Commentary on Aristotle's Politics. Indianapolis: Hackett publishing company, inc.

- Barker, Sir Ernest (1906). The Political Thought of Plato and Aristotle. London: Methuen.

- Davis, Michael (1996). The Politics of Philosophy: A Commentary on Aristotle's Politics. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Goodman, Lenn E.; Talisse, Robert B. (2007). Aristotle's Politics Today. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Keyt, David; Miller, Fred D. (1991). A Companion to Aristotle's Politics. Cambridge: Blackwell.

- Kraut, ed., Richard; Skultety, Steven (2005). Aristotle's Politics: Critical Essays. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - Simpson, Peter L. (1998). A Philosophical Commentary on the Politics of Aristotle. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Miller, Fred D. (1995). Nature, Justice, and Rights in Aristotle's Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mayhew, Robert (1997). Aristotle's Criticism of Plato's Republic. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Strauss, Leo (Ch. 1). The City and Man.

- Salkever, Stephen. Finding the Mean.

- Nussbaum, Martha. The Fragility of Goodness.

- Mara, Gerald. "Political Theory 23 (1995): 280–303". The Near Made Far Away.

- Frank, Jill. A Democracy of Distinction.

- Salkever, Stephen. The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Greek Political Theory.

External links

- Aristotle: Politics entry by Edward Clayton in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Miller, Fred. "Aristotle's Political Theory". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Aristotle's Politics on In Our Time at the BBC

Versions

- Politics, full text by Project Gutenberg, trans. by William Ellis

- English translation at Perseus Digital Library, translation by Harris Rackham

- Australian copy, trans. by Benjamin Jowett

- HTML , trans. by Benjamin Jowett

- PDF at McMaster, trans. by Benjamin Jowett

Politics public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Politics public domain audiobook at LibriVox