Toledo War

The Toledo War (1835–36), also known as the Michigan–Ohio War or the Ohio–Michigan War, was an almost bloodless boundary dispute between the U.S. state of Ohio and the adjoining territory of Michigan over what is now known as the Toledo Strip. Control of the mouth of the Maumee River and the inland shipping opportunities it represented, and the good farmland to the west were seen by both parties as valuable economic assets.

| Toledo War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The portion of the Michigan Territory claimed by the State of Ohio known as the Toledo Strip | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Ohio militia | Territory of Michigan militia | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Robert Lucas John Bell |

Stevens T. Mason Joseph W. Brown | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 600 | 1,000 | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| none | 1 wounded | ||||||||

| In exchange for ceding the Toledo Strip, all of what is now known as the Upper Peninsula was included within Michigan's bounds when it was admitted into the Union in 1837 (only the easternmost portion of the peninsula had been claimed in Michigan's 1835 statehood petition). | |||||||||

Poor geographical understanding of the Great Lakes helped produce conflicting state and federal legislation between 1787 and 1805, and varying interpretations of the laws led the governments of Ohio and Michigan to both claim jurisdiction over a 468-square-mile (1,210 km2) region along their border. The situation came to a head when Michigan petitioned for statehood in 1835 and sought to include the disputed territory within its boundaries. Both sides passed legislation attempting to force the other side's capitulation, and Ohio's Governor Robert Lucas and Michigan's 24-year-old "Boy Governor" Stevens T. Mason helped institute criminal penalties for residents submitting to the other's authority. Both states deployed militias on opposite sides of the Maumee River near Toledo, but besides mutual taunting, there was little interaction between the two forces. The single military confrontation of the "war" ended with a report of shots being fired into the air, incurring no casualties. The only blood spilled was the non-fatal stabbing of a law enforcement officer.

During the summer of 1836, the United States Congress proposed a compromise whereby Michigan gave up its claim to the strip in exchange for its statehood and the remaining three-quarters of the Upper Peninsula. The northern region's mineral wealth later became an economic asset to Michigan, but at the time the compromise was considered a poor deal for the new state, and voters in a statehood convention in September soundly rejected it. But in December, facing a dire financial crisis and pressure from Congress and President Andrew Jackson, the Michigan government called another convention (called the "Frostbitten Convention"), which accepted the compromise, resolving the Toledo War.

Origins

In 1787, the Congress of the Confederation enacted the Northwest Ordinance, which created the Northwest Territory in what is now the upper Midwestern United States. The Ordinance specified that the territory was eventually to be divided into "not less than three nor more than five" future states. One of the boundaries between them was to be "an east and west line drawn through the southerly bend or extreme of Lake Michigan".[1] When Congress passed the Enabling Act of 1802, which authorized Ohio to begin the process of becoming a U.S. state, the language defining Ohio's northern boundary elaborated on that, but was fundamentally the same: "an east and west line drawn through the southerly extreme of Lake Michigan, running east ... until it shall intersect Lake Erie or the territorial line [with British North America, now Canada], and thence with the same through Lake Erie to the Pennsylvania line aforesaid".[2]

The most highly regarded map of the time, the "Mitchell Map",[3] showed the southerly extreme of Lake Michigan at a latitude north of the mouth of the Detroit River, suggesting that an east–west line would not intersect with Lake Erie at all, until well across the international border. The framers of the 1802 Ohio Constitution therefore believed it was the intent of Congress that Ohio's northern boundary should certainly be north of the mouth of the Maumee River, and possibly even of the Detroit River. Ohio would thus be granted access to most or all of the Lake Erie shoreline west of Pennsylvania, and any other new states carved out of the Northwest Territory would have access to only Lakes Michigan, Huron, or Superior.[4]

However, the delegates allegedly received reports from a fur trapper that Lake Michigan extended significantly farther south than had previously been believed (or mapped). Thus, it was possible that an east–west line extending east from Lake Michigan's southern tip might intersect Lake Erie somewhere southeast of Maumee Bay, or worse, might not intersect the lake at all; the farther south that Lake Michigan actually extended, the more land Ohio would lose, conceivably even the entire Lake Erie shoreline west of Pennsylvania.[4]

Addressing this contingency, the Ohio delegates included a provision in the draft Ohio constitution that if this report about Lake Michigan's position was correct, the state boundary line would be angled slightly northeast so as to intersect Lake Erie at the "most northerly cape of the Miami [Maumee] Bay". This provision would guarantee that most of the Maumee River watershed and the southern shore of Lake Erie west of Pennsylvania would fall in Ohio.[4] The draft constitution with this proviso was accepted by the United States Congress, but before Ohio's admission to the Union in February 1803, the proposed constitution was referred to a Congressional committee. The committee's report stated that the clause defining the northern boundary depended on "a fact not yet ascertained" (the latitude of the southern extreme of Lake Michigan), and the members "thought it unnecessary to take it [the provision], at the time, into consideration."[5]

When Congress created the Michigan Territory in 1805, it used the Northwest Ordinance's language to define the territory's southern boundary, disregarding that provision in Ohio's state constitution. This difference, and its potential ramifications, apparently went unnoticed at the time, but it established the legal basis for the conflict that would erupt 30 years later.[4]

Creation of the Toledo Strip

The location of the border was contested throughout the early 19th century. Residents of the Port of Miami—which would later become Toledo—urged the Ohio government to resolve the border issue. The Ohio legislature, in turn, passed repeated resolutions and requests asking Congress to take up the matter. In 1812, Congress approved a request for an official survey of the line.[6] Delayed because of the War of 1812, it was only after Indiana's admission to the Union in 1816 that work on the survey commenced. At that time, the border between Michigan and Indiana was altered from the Northwest Ordinance boundary – over the protests of the Michigan Territory – moving it 10 miles (16 km) northward to give the new state substantial frontage on Lake Michigan.[7]

U.S. Surveyor General Edward Tiffin, who was in charge of the survey, was a former Ohio governor, and employed William Harris to survey not the Ordinance Line, but the line described in the Ohio Constitution of 1802. When completed, the "Harris Line" placed the mouth of the Maumee River completely in Ohio, as intended by the drafters of the state constitution.[8] When the results of the survey were made public, Michigan territorial governor Lewis Cass objected, writing in a letter to Tiffin that the survey was biased to favor Ohio and "is only adding strength to the strong, and making the weak still weaker."[9]

In response, Michigan commissioned a second survey that was carried out by John A. Fulton. The Fulton survey was based upon the original 1787 Ordinance Line, and after measuring the line eastward from Lake Michigan to Lake Erie, it found the Ohio boundary to lie just southeast of the mouth of the Maumee River.[10] The region between the Harris and Fulton survey lines formed what is now known as the "Toledo Strip". This ribbon of land between northern Ohio and southern Michigan spanned a region five to eight miles (8 to 13 km) wide, over which both jurisdictions claimed sovereignty. While Ohio refused to cede its claim, Michigan quietly occupied it for the next several years, setting up local governments, building roads, and collecting taxes throughout the area.[9]

Economic significance

The Toledo Strip was and still is a commercially important area. Prior to the rise of the railroad industry, rivers and canals were the major "highways of commerce" in the American Midwest.[11] A small but important part of the Strip—the area around present-day Toledo and Maumee Bay—fell within the Great Black Swamp, and this area was nearly impossible to navigate by road, especially after spring and summer rains.[12] Draining into Lake Erie, the Maumee River was not necessarily well-suited for large ships, but it did provide an easy connection to Indiana's Fort Wayne.[11] At the time, there were plans to connect the Mississippi River and the Great Lakes through a series of canals. One such canal system approved by the Ohio legislature in 1825 was the Miami and Erie Canal that included a connection to the Ohio River and an outflow into Lake Erie via the Maumee River.[8]

During the conflict over the Toledo Strip, the Erie Canal was built, linking New York City and the Eastern seaboard to the Great Lakes at Buffalo. The canal finished in 1825, and immediately became a major route for trade and migration. Corn and other farm products (from the Midwest) could be shipped to eastern markets for much less expense than the older route along the Mississippi River. In addition, the migration of settlers to the Midwest increased sharply after the canal was finished, turning Buffalo and other port cities into boomtowns.[13]

The success of the Erie Canal inspired many other canal projects. Because the western end of Lake Erie offered the shortest overland route to the frontiers of Indiana and Illinois, Maumee Harbor was seen as a site of immediate importance and great value. Detroit was 20 miles (32 km) up the Detroit River from Lake Erie, and faced the difficult barrier of the Great Black Swamp to the south. Because of this, Detroit was less suited to new transportation projects such as canals, and later railroads, than was Toledo. From this perspective on the rapidly developing Midwest of the 1820s and 1830s, both states had much to gain by controlling the land in the Toledo Strip.[13]

In addition, the Strip west of the Toledo area is good for agriculture, because of its well-drained, fertile loam soil. The area had for many years produced large amounts of corn and wheat per acre.[12] Michigan and Ohio both wanted what seemed strategically and economically destined to become an important port and prosperous farmland.[11]

Prelude to conflict

In 1820–21, the federal land surveys had reached the disputed area from two directions, progressing southward from a baseline in Michigan and northward from one in Ohio. For unknown reasons, Surveyor General Tiffin ordered the two surveys to close on the Northwest Ordinance (Fulton) line, rather than Harris' line, perhaps lending implicit support to Michigan's claims over Ohio's.[14] Thus, townships that were established north of the line assumed they were part of the Michigan Territory. By the early 1820s, the growing Michigan Territory reached the minimum population threshold of 60,000 to qualify for statehood. When it sought to hold a state constitutional convention in 1833, Congress rejected the request because of the still-disputed Toledo Strip.[10]

Ohio asserted that the boundary was firmly established in its constitution and thus Michigan's citizens were simply intruders; the state government refused to negotiate the issue with them. The Ohio Congressional delegation was active in blocking Michigan from attaining statehood, lobbying other states to vote against it. In January 1835, frustrated by the political stalemate, Michigan's territorial governor Stevens T. Mason called for a constitutional convention to be held in May of that year, despite Congress' refusal to approve an enabling act authorizing one.[15]

In February 1835, Ohio passed legislation that set up county governments in the Strip. The county in which Toledo sat would, later in 1835, be named after incumbent Governor Robert Lucas, a move that further exacerbated the growing tensions with Michigan. Also, during this period, Ohio attempted to use its power in Congress to revive a previously rejected boundary bill that would formally set the state border to be the Harris Line.[16]

Michigan, led by the young and hot-headed Mason, responded with the passage of the Pains and Penalties Act just six days after Lucas County was formed; the act made it a criminal offense for Ohioans to carry out governmental actions in the Strip, under penalty of a fine up to $1,000 (equivalent to $26,000 in 2021), up to five years imprisonment at hard labor, or both.[17][18] Acting as commander-in-chief of the territory, Mason appointed Brigadier General Joseph W. Brown of the Third U.S. Brigade to head the state militia, with the instructions to be ready to act against Ohio trespassers. Lucas obtained legislative approval for a militia of his own, and he soon sent forces to the Strip area. The Toledo War had begun.[10]

Former United States President John Quincy Adams, who at the time represented Massachusetts in Congress, backed Michigan's claim. In 1833, when Congress rejected Michigan's request for a convention, Adams summed up his opinion on the dispute: "Never in the course of my life have I known a controversy of which all the right was so clearly on one side and all the power so overwhelmingly on the other."[19]

War

Acting as commander-in-chief of Ohio's militia, Governor Lucas—along with General John Bell and about 600 other fully armed militiamen—arrived in Perrysburg, Ohio, 10 miles (16 km) southwest of Toledo, on March 31, 1835.[20] Shortly thereafter, Governor Mason and General Brown arrived to occupy the city of Toledo proper with around 1,000 armed men, intending to prevent Ohio advances into the Toledo area as well as stopping further border marking from taking place.[21]

Presidential intervention

In a desperate attempt to prevent armed battle and to avert the resulting political crisis, U.S. President Andrew Jackson consulted his Attorney General, Benjamin Butler, for his legal opinion on the border dispute. At the time, Ohio was a growing political power in the Union, with 19 U.S. representatives and two senators. In contrast, Michigan, still a territory, had only a single non-voting delegate. Ohio was a crucial swing state in presidential elections, and it would have been devastating to the fledgling Democratic Party to lose its electoral votes. Jackson calculated that his party's best interest would be served by keeping the Toledo Strip as part of Ohio.[22] However, Butler held that until Congress dictated otherwise, the land rightfully belonged to Michigan. This presented a political dilemma for Jackson that spurred him to take action that would greatly influence the outcome.[22]

On April 3, 1835, Jackson sent two representatives from Washington, D.C. – Richard Rush of Pennsylvania and Benjamin Chew Howard of Maryland – to Toledo to arbitrate the conflict and present a compromise to both governments. The proposal, presented on April 7, recommended that a re-survey to mark the Harris Line commence without further interruption by Michigan, and that the residents of the affected region be allowed to choose their own state or territorial governments until Congress could definitively settle the matter.[23]

Lucas reluctantly agreed to the proposal and began to disband his militia, believing the debate to be settled. Three days later, elections in the region were held under Ohio law. Mason refused the deal and continued to prepare for possible armed conflict.[23][24]

During the elections, Ohio officials were harassed by Michigan authorities, and the area residents were threatened with arrest if they submitted to Ohio's authority.[25] On April 8, 1835, the Monroe County, Michigan sheriff arrived at the home of Major Benjamin F. Stickney, an Ohio partisan. In the first contact between Michigan partisans and the Stickney family, the sheriff arrested two Ohioans under the Pains and Penalties Act on the basis that the men had voted in the Ohio elections.[26]

Battle of Phillips Corners

After the election, Lucas believed that the commissioners' actions had alleviated the situation and once again sent out surveyors to mark the Harris Line. The project proceeded without serious incident until April 26, 1835, when the surveying group was attacked by 50 to 60 members of General Brown's militia in the Battle of Phillips Corners.[22][27] As the only site of armed conflict, the battle's name is sometimes used as a synonym for the entire Toledo War.

Surveyors wrote to Lucas afterward that while observing "the blessings of the Sabbath", Michigan militia forces advised them to retreat. In the ensuing chase, "nine of our men, who did not leave the ground in time after being fired upon by the enemy, from thirty to fifty shots, were taken prisoners and carried away into Tecumseh, Michigan."[28] While the details of the attack are disputed—Michigan claimed it fired no shots, only discharging a few musket rounds in the air as the Ohio group retreated—the battle further infuriated both Ohioans and Michiganders and brought the two sides to the brink of all-out war.[29][30]

Bloodshed in 1835

In response to allegations that Michigan's militia fired upon Ohioans, Lucas called a special session of Ohio's legislature on June 8 to pass several more controversial acts, including the establishment of Toledo as the county seat of Lucas County, the establishment of a Court of Common Pleas in the city, a law to prevent the forcible abduction of Ohio citizens from the area, and a budget of $300,000 ($8.2 million in 2020[31]) to implement the legislation.[30] Michigan's territorial legislature responded with a budget appropriation of $315,000 to fund its militia.[10]

In May and June, Michigan drafted a state constitution, with provisions for a bicameral legislature, a supreme court, and other components of a functional state government.[30][32] Congress was still not willing to allow Michigan's entry into the Union, and Jackson vowed to reject Michigan's statehood until the border issue and "war" were resolved.[33]

Lucas ordered his adjutant general, Samuel C. Andrews, to conduct a count of the militia, and was told that 10,000 volunteers were ready to fight. That news became exaggerated as it traveled north, and soon thereafter the Michigan territorial press dared the Ohio "million" to enter the Strip as they "welcomed them to hospitable graves".[34]

In June 1835, Lucas dispatched a delegation consisting of U.S. Attorney Noah Haynes Swayne, former Congressman William Allen, and David T. Disney to Washington D.C. to confer with Jackson. The delegation presented Ohio's case and urged Jackson to address the situation swiftly.[35][36]

Throughout mid-1835, both governments continued their practice of oneupmanship, and constant skirmishes and arrests occurred. Citizens of Monroe County joined together in a posse to make arrests in Toledo. Partisans from Ohio, angered by the harassment, targeted the offenders with criminal prosecutions.[37] Lawsuits were rampant and served as a basis for retaliatory lawsuits from the opposite side.[37] Partisans of both sides organized spying parties to keep track of the sheriffs of Wood County, Ohio, and Monroe County, Michigan, who were entrusted with the security of the border.[37]

On July 15, Monroe County, Michigan, Deputy Sheriff Joseph Wood went into Toledo to arrest Major Benjamin Stickney, but when Stickney and his family resisted, the whole family was subdued and taken into custody.[37] During the scuffle, the major's son Two Stickney stabbed Wood with a penknife and fled into Ohio. Wood's injuries were not life-threatening.[29] When Lucas refused Mason's demand to extradite Two Stickney to Michigan for trial, Mason wrote to Jackson for help, suggesting that the matter be referred to the United States Supreme Court. At the time of the conflict it was not established that the Supreme Court could resolve state boundary disputes, and Jackson declined the request.[38] Looking for peace, Lucas began making his own efforts to end the conflict, again through federal intervention via Ohio's congressional delegation.[36]

In August 1835, at the strong urging of Ohio's members of Congress, Jackson removed Mason as Michigan's territorial governor and appointed John S. ("Little Jack") Horner in his stead. Before his replacement arrived, Mason ordered 1,000 Michigan militiamen to enter Toledo and prevent the symbolically important first session of the Ohio Court of Common Pleas. While the idea was popular with Michigan residents, the effort failed: the judges held a midnight court before quickly retreating south of the Maumee River, where Ohio forces were positioned.[39]

Frostbitten Convention and the end of the Toledo War

Horner proved extremely unpopular as governor and his tenure was very short. Residents disliked him so much they burned him in effigy and pelted him with vegetables upon his entry into the territorial capital. In the October 1835 elections, voters approved the draft constitution and re-elected Mason governor. The same election saw Isaac E. Crary chosen as Michigan's first U.S. Representative to Congress. Because of the dispute Congress refused to accept his credentials and seated him as a non-voting delegate. The two U.S. Senators chosen by the state legislature in November, Lucius Lyon and John Norvell, were treated with even less respect, being allowed to sit only as spectators in the Senate gallery.[10]

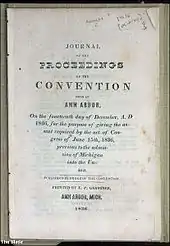

On June 15, 1836, Jackson signed a bill that allowed Michigan to become a state, but only after it ceded the Toledo Strip. In exchange for this concession, Michigan would be granted the western three-quarters of what is now known as the Upper Peninsula (the easternmost portion had already been included in the state boundaries).[40] Because of the perceived worthlessness of the Upper Peninsula's remote wilderness, which was ill-suited for agriculture, a September 1836 special convention in Ann Arbor rejected the offer.[41]

As the year wore on, Michigan found itself deep in financial crisis, nearly bankrupt because of the high militia expenses. The government was spurred to action by the realization that a $400,000 surplus ($10 million in 2020[31]) in the United States Treasury was about to be distributed to the 25 states but not to territorial governments; Michigan would have been ineligible to receive a share.[32]

The "war" unofficially ended on December 14, 1836, at a second convention in Ann Arbor. Delegates passed a resolution to accept Congress's terms. The calling of the convention was itself controversial. It came about only because of an upswelling of private summonses, petitions, and public meetings. Since the legislature did not approve a call to convention, some said the convention was illegal. Whigs boycotted the convention. As a consequence, the resolution was ridiculed by many Michigan residents.[41] Congress questioned the convention's legality, but accepted its results. Because of these factors, as well as a notable cold spell, the event became known as the Frostbitten Convention.[41]

On January 26, 1837, Michigan was admitted to the Union as the 26th state,[42] without the Toledo Strip but with the entire Upper Peninsula.[41]

Subsequent history

The Toledo strip became a permanent part of Ohio. The Upper Peninsula was considered a worthless wilderness by almost all familiar with the area, valuable only for timber and fur trapping.[43] However, the discovery of copper in the Keweenaw Peninsula and iron in the Central Upper Peninsula in the 1840s led to a mining boom that lasted long into the 20th century.[44] Michigan's loss of 1,100 square miles (2,800 km2) of agricultural land and the port of Toledo was offset by the gain of 9,000 square miles (23,000 km2) of timber and ore-rich land.[26]

Differences of opinion about the exact boundary location continued until a definitive re-survey was performed in 1915. Re-survey protocol ordinarily required the surveyors to follow the Harris line exactly, but in this case, the surveyors deviated from it in places. This was done to prevent certain residents near the border from being subject to changes in state residence and land owners from having parcels in both states. The 1915 survey was delineated by 71 granite markers, 12 inches (30 cm) wide by 18 inches (46 cm) high. Upon completion, the two states' governors, Woodbridge N. Ferris of Michigan and Frank B. Willis of Ohio, shook hands at the border.[8]

Traces of the original Ordinance Line can still be seen in northwestern Ohio and northern Indiana. The northernmost boundaries of Ottawa and Wood counties follow it, as well as many township boundaries in Fulton and Williams counties. Many old north–south roads are offset as they cross the line, forcing traffic to jog east while traveling north. The line is identified on United States Geological Survey topographical maps as the "South [Boundary] Michigan Survey", and on Lucas County and Fulton County road maps as "Old State Line Road".[45][46]

While the land border was firmly set in the early 20th century, the two states still disagreed on the path of the border to the east, in Lake Erie.[47] In 1973, they finally obtained a hearing before the U.S. Supreme Court on their competing claims to the Lake Erie waters. In Michigan v. Ohio, the court upheld a special master's report and ruled that the boundary between the two states in Lake Erie was angled to the northeast, as described in Ohio's state constitution, and not a straight east–west line.[48] One consequence of the decision was that Turtle Island, just outside Maumee Bay and originally treated as wholly in Michigan, was split between the two states.[49]

This decision was the last border adjustment, putting an end to years of debate. In modern times, although a general rivalry between Michiganders and Ohioans persists, overt conflict between the states is restricted primarily to the Michigan–Ohio State rivalry in American football and to a lesser degree to the rivalry between the Detroit Tigers and Cleveland Guardians in American League baseball;[50] the Toledo War is sometimes cited as the origin of the animosity represented in today's rivalry.[51]

USGS topographic map that shows the Ordinance Line as "South Bdy Michigan Survey". There are jogs in many north–south roads at this line.

USGS topographic map that shows the Ordinance Line as "South Bdy Michigan Survey". There are jogs in many north–south roads at this line. Michigan Governor Woodbridge N. Ferris and Ohio Governor Frank B. Willis shake on a truce over state line markers erected in 1915.

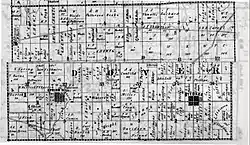

Michigan Governor Woodbridge N. Ferris and Ohio Governor Frank B. Willis shake on a truce over state line markers erected in 1915. The northern tier of townships in Williams County are within the Toledo Strip. The southern boundary of each lies along the Ordinance Line.[52]

The northern tier of townships in Williams County are within the Toledo Strip. The southern boundary of each lies along the Ordinance Line.[52] The northern half of Dover Township in Fulton County Ohio, formerly claimed by Michigan, is shifted, or "jogs", at "Old State Line Road", now County Road K.

The northern half of Dover Township in Fulton County Ohio, formerly claimed by Michigan, is shifted, or "jogs", at "Old State Line Road", now County Road K.

See also

- List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States

- List of Michigan county name etymologies

- Michigan Constitution

- Ohio Lands

- Timeline of the Toledo Strip

- Ohio State-Michigan football rivalry

References

Footnotes

- "Northwest Ordinance". The Avalon Project. Yale Law School. July 13, 1787. Archived from the original on May 23, 2006. Retrieved May 12, 2006.

- "Enabling Act of 1802". United States Congress. April 30, 1802. § 2. Archived from the original on March 21, 2015 – via Wikisource.

- Edney, Matthew H. "The Mitchell Map, 1755–1782: An Irony of Empire". University of Southern Maine. Archived from the original on December 25, 2014. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- Mendenhall & Graham (1895), pp. 127, 154

- Mendenhall & Graham (1895), p. 153.

- Mendenhall & Graham (1895), p. 206.

- Hayden, Maureen. "Retracing a Border Incites Tensions Between Indiana, Michigan". News and Tribune. Jeffersonville, Indiana. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

- "The Toledo War". Geography of Michigan and the Great Lakes Region. Michigan State University. Archived from the original on August 20, 2006. Retrieved May 12, 2006.

- Mendenhall & Graham (1895), p. 162.

- Public Affairs Office (March 4, 2002). "The Toledo War". Michigan Department of Military and Veteran Affairs. Archived from the original on February 9, 2006. Retrieved May 12, 2006.

- Mendenhall & Graham (1895), p. 154.

- "The Great Black Swamp". Historic Perrysburg. Archived from the original on February 18, 2007. Retrieved May 12, 2006.

- Meinig (1993), pp. 357, 363, 436, and 440

- Sherman, C.E. & Schlesinger, A. M. (1916). Volume 1, Ohio-Michigan Boundary. Final Report, Ohio Cooperative Topographic Survey (Report).

- Mendenhall & Graham (1895), p. 167.

- Galloway (1895), p. 208.

- "S.013 Monument". Detroit Historical Society and Detroit Historical Society. Archived from the original on September 29, 2006. Retrieved August 10, 2006.

- "Important Dates in Michigan's Quest for Statehood". State of Michigan. January 1, 2001. Archived from the original on May 9, 2006. Retrieved May 12, 2006.

- Adams (1876), pp. 214–5.

- Galloway (1895), p. 213.

- Way (1869), p. 17.

- Galloway (1895), p. 214.

- Way (1869), p. 19.

- Galloway (1895), p. 216.

- Wittke (1895), pp. 299, 303.

- Mitchell (2004), p. 7.

- "The Ohio–Michigan Boundary War: Battle of Phillips Corners Marker #2–26". Remarkable Ohioan. Archived from the original on November 22, 2015. Retrieved May 13, 2006.

- Galloway (1895), p. 217.

- Wittke (1895), p. 306.

- Galloway (1895), p. 220.

- Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2022). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved February 12, 2022. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the Measuring Worth series.

- Baker, Patricia J. (January 1, 2001). "Stevens Thompson Mason". State of Michigan. Archived from the original on May 9, 2006. Retrieved May 13, 2006.

- Galloway (1895), p. 227.

- Way (1869), p. 28.

- Way (1869), p. 33.

- Galloway (1895), p. 221.

- Way (1869), p. 29.

- Dunbar & May (1995), p. 216.

- Mendenhall & Graham (1895), p. 199.

- Galloway (1895), p. 228.

- Wittke (1895), p. 318.

- "Michigan Quarter". U.S. Mint. Archived from the original on June 14, 2006. Retrieved May 13, 2006.

- Wittke (1895), p. 319.

- "History of the Upper Peninsula". Northern Michigan University. Archived from the original on May 16, 2006. Retrieved May 13, 2006.

- United States Geological Survey (July 1, 1983). 2 km NE of Wilkins, Ohio, United States (Map). Microsoft Research Maps. Retrieved May 13, 2006.

- Ohio Department of Transportation. Lucas County, Ohio (PDF) (Map). Scale not given. Columbus: Ohio Department of Transportation. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 29, 2010. Retrieved October 5, 2008.

- Kienzle, Javan (March 29, 2009). "How Ohio's Grab for the Maumee River Blocked Michigan's Road to Statehood". Detroit Free Press.

- Michigan v. Ohio, 410 U.S. 420 (1973).

- Strock, Jenson (February 22, 2022). "1973: The U.S. Supreme Court decides the boundary line between Ohio and Michigan" (Video). Today in Toledo History. Toledo, Ohio: WTOL-TV. 0:53. Retrieved April 5, 2022 – via YouTube.

- Emmanuel, Greg (2004). The 100-Yard War: Inside the 100-Year-Old Michigan–Ohio State Football Rivalry. Hoboken, NJ: J. Wiley & Sons. pp. 8–10. ISBN 0-471-67552-0.

- Unger, Brian (April 6, 2010). "How the States Got Their Shapes". How the States Got Their Shapes. Season 1. Episode 1. The History Channel.

- Maynard, Kevin (June 9, 2020). "Williams County was created 200 years ago". The Bryan Times. Bryan, Ohio. Retrieved March 28, 2021.

Works cited

- Adams, John Quincy (1876). Adams, Charles Francis (ed.). Memoirs of John Quincy Adams: Comprising Portions of His Diary from 1795 to 1848. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. p. 214. Retrieved April 6, 2012.

Never in the course of my life have I known a controversy of which all the right.

- Allen, R.C. (July 30, 1916). "Biennial Report of the Directory and Report on Retracement and Report on Retracement Permanent Monumenting of the Michigan–Ohio Boundary". Michigan Geological and Biological Survey. Lansing, MI: Wynkoop Hallenbeck Crawford Co., State Printers. OCLC 11743219. Publication 22, Geological Series 18.

- Dunbar, Willis F. & May, George S. (1995). Michigan: A History of the Wolverine State (3rd Revised ed.). Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-7055-1.

- Emmanuel, Greg (1960). "Hate: The Early Years". The 100-Yard War: Inside the 100-Year-Old Michigan–Ohio State Football Rivalry. New York: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 9–10. ISBN 0-471-67552-0.

- Galloway, Tod B. (1895). "The Ohio-Michigan Boundary Line Dispute". Ohio Archaeological and Historical Quarterly. 4: 213. OCLC 44843819.

- Meinig, D.W. (1993). The Shaping of America: A Geographical Perspective on 500 Years of History. Volume 2, Continental America, 1800–1867. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-05658-3.

- Mendenhall, T.C. & Graham, A.A. (1895). "Boundary Line Between Ohio and Indiana, and Between Ohio and Michigan". Ohio Archaeological and Historical Quarterly. 4: 127. OCLC 44843819.

- Mitchell, Gordon (July 2004). "History Corner: Ohio–Michigan Boundary War, Part 2". Professional Surveyor Magazine. 24 (7): 7. Archived from the original on August 23, 2007.

- Way, Willard V. (1869). Facts and Historical Events of the Toledo War of 1835. Toledo: Daily Commercial Steam Book and Job Printing House. OCLC 490964723.

- Wittke, Karl (1895). "The Ohio-Michigan Boundary Dispute Re-examined". Ohio Archaeological and Historical Quarterly. 45: 299. OCLC 44843819.

Further reading

- Bulkley, John McClelland (1913). "Toledo War". History of Monroe County, Michigan: A Narrative Account of Its Historical Progress, Its People, and Its Principal Interests. Chicago: Lewis Publishing. pp. 137–161. Retrieved May 8, 2006.

- Faber, Don (2008). The Toledo War: The First Michigan–Ohio Rivalry. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-07054-1.

- Google (June 9, 2015). "Map Showing Jog from West to East for Northerly Traffic and Indicating the Approximate Location of the Original Boundary Line" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved June 9, 2015.

- Greene, Merritt (1960). Curse of the White Panther: A Story of the Days of the Toledo War. Hillsdale, MI: Hillsdale School Supply.

- Hemans, Lawton T. (1920). Life and Times of Stevens Thomson Mason: The Boy Governor of Michigan. Lansing: Michigan Historical Commission.

- Karl-George, Mary (1971). The Rise and Fall of Toledo, Michigan: The Toledo War!. Lansing: Michigan Historical Commission.

- Michigan Department of Natural Resources. Michigan Becomes a State (Michigan Historical Marker). Ann Arbor: Michigan Department of Natural Resources. Archived from the original on March 25, 2006.

- Naldrett, Alan (2007). "Holy Toledo! Or the Continuing War Between Ohio and Michigan ..." (PDF). Macomb County, Michigan. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 10, 2008.

- Toledo War at Ohio History Central

- "ToledoWar.com". ToledoWar.com. April 14, 2005. Archived from the original on March 6, 2008.

- Tuttle, Charles R. (1873). "Chapter XXXI". General History of the State of Michigan: With Biographical Sketches, Portrait Engravings, and Numerous Illustrations. Detroit: R.D.S. Tyler. pp. 448–479. ISBN 0-665-42277-6. Retrieved May 8, 2006.

- United States Congress (1860). "Thursday, June 5, 1843, 'Northern Boundary of Ohio'". Abridgment of the Debates of Congress, from 1789 to 1856. New York: D. Appleton. pp. 367–370. ISBN 1-4255-6619-7. Retrieved May 8, 2006.