Trumpet

The trumpet is a brass instrument commonly used in classical and jazz ensembles. The trumpet group ranges from the piccolo trumpet—with the highest register in the brass family—to the bass trumpet, pitched one octave below the standard B♭ or C trumpet.

Trumpet in B♭ | |

| Brass instrument | |

|---|---|

| Classification | |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 423.233 (Valved aerophone sounded by lip vibration) |

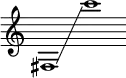

| Playing range | |

| |

| Related instruments | |

| flugelhorn, cornet, cornett, flumpet, bugle, natural trumpet, bass trumpet, post horn, Roman tuba, buccina, cornu, lituus, shofar, dord, dung chen, sringa, shankha, lur, didgeridoo, alphorn, Russian horns, serpent, ophicleide, piccolo trumpet, horn, alto horn, baritone horn, pocket trumpet | |

| Part of a series on |

| Musical instruments |

|---|

Trumpet-like instruments have historically been used as signaling devices in battle or hunting, with examples dating back to at least 1500 BC. They began to be used as musical instruments only in the late 14th or early 15th century.[1] Trumpets are used in art music styles, for instance in orchestras, concert bands, and jazz ensembles, as well as in popular music. They are played by blowing air through nearly-closed lips (called the player's embouchure), producing a "buzzing" sound that starts a standing wave vibration in the air column inside the instrument.[2] Since the late 15th century, trumpets have primarily been constructed of brass tubing, usually bent twice into a rounded rectangular shape.

There are many distinct types of trumpet, with the most common being pitched in B♭ (a transposing instrument), having a tubing length of about 1.48 m (4 ft 10 in). Early trumpets did not provide means to change the length of tubing, whereas modern instruments generally have three (or sometimes four) valves in order to change their pitch. Most trumpets have valves of the piston type, while some have the rotary type. The use of rotary-valved trumpets is more common in orchestral settings (especially in German and German-style orchestras), although this practice varies by country. A musician who plays the trumpet is called a trumpet player or trumpeter.[3]

Etymology

The English word "trumpet" was first used in the late 14th century.[4] The word came from Old French "trompette," which is a diminutive of trompe.[4] The word "trump," meaning "trumpet," was first used in English in 1300. The word comes from Old French trompe "long, tube-like musical wind instrument" (12c.), cognate with Provençal tromba, Italian tromba, all probably from a Germanic source (compare Old High German trumpa, Old Norse trumba "trumpet"), of imitative origin."[5]

History

The earliest trumpets date back to 1500 BC and earlier. The bronze and silver Tutankhamun's trumpets from his grave in Egypt, bronze lurs from Scandinavia, and metal trumpets from China date back to this period.[6] Trumpets from the Oxus civilization (3rd millennium BC) of Central Asia have decorated swellings in the middle, yet are made out of one sheet of metal, which is considered a technical wonder for its time.[7]

The Shofar, made from a ram horn and the Hatzotzeroth, made of metal, are both mentioned in the Bible. They were said to have been played in Solomon's Temple around 3,000 years ago. They were said to be used to blow down the walls of Jericho. They are still used on certain religious days.[8] The Salpinx was a straight trumpet 62 inches (1,600 mm) long, made of bone or bronze. Salpinx contests were a part of the original Olympic Games.[8]

The Moche people of ancient Peru depicted trumpets in their art going back to AD 300.[9] The earliest trumpets were signaling instruments used for military or religious purposes, rather than music in the modern sense;[10] and the modern bugle continues this signaling tradition.

Improvements to instrument design and metal making in the late Middle Ages and Renaissance led to an increased usefulness of the trumpet as a musical instrument. The natural trumpets of this era consisted of a single coiled tube without valves and therefore could only produce the notes of a single overtone series. Changing keys required the player to change crooks of the instrument.[8] The development of the upper, "clarino" register by specialist trumpeters—notably Cesare Bendinelli—would lend itself well to the Baroque era, also known as the "Golden Age of the natural trumpet." During this period, a vast body of music was written for virtuoso trumpeters. The art was revived in the mid-20th century and natural trumpet playing is again a thriving art around the world. Many modern players in Germany and the UK who perform Baroque music use a version of the natural trumpet fitted with three or four vent holes to aid in correcting out-of-tune notes in the harmonic series.[11]

The melody-dominated homophony of the classical and romantic periods relegated the trumpet to a secondary role by most major composers owing to the limitations of the natural trumpet. Berlioz wrote in 1844:

Notwithstanding the real loftiness and distinguished nature of its quality of tone, there are few instruments that have been more degraded (than the trumpet). Down to Beethoven and Weber, every composer – not excepting Mozart – persisted in confining it to the unworthy function of filling up, or in causing it to sound two or three commonplace rhythmical formulae.[12]

Construction

The trumpet is constructed of brass tubing bent twice into a rounded oblong shape.[13] As with all brass instruments, sound is produced by blowing air through closed lips, producing a "buzzing" sound into the mouthpiece and starting a standing wave vibration in the air column inside the trumpet. The player can select the pitch from a range of overtones or harmonics by changing the lip aperture and tension (known as the embouchure).

The mouthpiece has a circular rim, which provides a comfortable environment for the lips' vibration. Directly behind the rim is the cup, which channels the air into a much smaller opening (the back bore or shank) that tapers out slightly to match the diameter of the trumpet's lead pipe. The dimensions of these parts of the mouthpiece affect the timbre or quality of sound, the ease of playability, and player comfort. Generally, the wider and deeper the cup, the darker the sound and timbre.

Modern trumpets have three (or, infrequently, four) piston valves, each of which increases the length of tubing when engaged, thereby lowering the pitch. The first valve lowers the instrument's pitch by a whole step (two semitones), the second valve by a half step (one semitone), and the third valve by one and a half steps (three semitones). Having three valves provides eight possible valve combinations (including "none"), but only seven different tubing lengths, because the third valve alone gives essentially the same tubing length as the 1–2 combination. (In practice there is often a deliberately-designed slight difference between "1–2" and "3", and in that case trumpet players will select the alternative that gives the best tuning for the particular note being played.) When a fourth valve is present, as with some piccolo trumpets, it usually lowers the pitch a perfect fourth (five semitones). Used singly and in combination these valves make the instrument fully chromatic, i.e., able to play all twelve pitches of classical music. For more information about the different types of valves, see Brass instrument valves.

The pitch of the trumpet can be raised or lowered by the use of the tuning slide. Pulling the slide out lowers the pitch; pushing the slide in raises it. To overcome the problems of intonation and reduce the use of the slide, Renold Schilke designed the tuning-bell trumpet. Removing the usual brace between the bell and a valve body allows the use of a sliding bell; the player may then tune the horn with the bell while leaving the slide pushed in, or nearly so, thereby improving intonation and overall response.[14]

A trumpet becomes a closed tube when the player presses it to the lips; therefore, the instrument only naturally produces every other overtone of the harmonic series. The shape of the bell makes the missing overtones audible.[15] Most notes in the series are slightly out of tune and modern trumpets have slide mechanisms for the first and third valves with which the player can compensate by throwing (extending) or retracting one or both slides, using the left thumb and ring finger for the first and third valve slides respectively.

Trumpets can be constructed from other materials, including plastic.[16]

Types

The most common type is the B♭ trumpet, but A, C, D, E♭, E, low F, and G trumpets are also available. The C trumpet is most common in American orchestral playing, where it is used alongside the B♭ trumpet. Orchestral trumpet players are adept at transposing music at sight, frequently playing music written for the A, B♭, D, E♭, E, or F trumpet on the C trumpet or B♭ trumpet.

The smallest trumpets are referred to as piccolo trumpets. The most common models are built to play in both B♭ and A, with separate leadpipes for each key. The tubing in the B♭ piccolo trumpet is one-half the length of that in a standard B♭ trumpet. Piccolo trumpets in G, F and C are also manufactured, but are less common. Many players use a smaller mouthpiece on the piccolo trumpet, which requires a different sound production technique from the B♭ trumpet and can limit endurance. Almost all piccolo trumpets have four valves instead of three—the fourth valve usually lowers the pitch by a fourth, making some lower notes accessible and creating alternate fingerings for certain trills. Maurice André, Håkan Hardenberger, David Mason, and Wynton Marsalis are some well-known trumpet players known for their virtuosity on the piccolo trumpet.

Trumpets pitched in the key of low G are also called sopranos, or soprano bugles, after their adaptation from military bugles. Traditionally used in drum and bugle corps, sopranos employ either rotary valves or piston valves.

The bass trumpet is at the same pitch as a trombone and is usually played by a trombone player,[3] although its music is written in treble clef. Most bass trumpets are pitched in either C or B♭. The C bass trumpet sounds an octave lower than written, and the B♭ bass sounds a major ninth (B♭) lower, making them both transposing instruments.

The historical slide trumpet was probably first developed in the late 14th century for use in alta cappella wind bands. Deriving from early straight trumpets, the Renaissance slide trumpet was essentially a natural trumpet with a sliding leadpipe. This single slide was awkward, as the entire instrument moved, and the range of the slide was probably no more than a major third. Originals were probably pitched in D, to fit with shawms in D and G, probably at a typical pitch standard near A=466 Hz. No known instruments from this period survive, so the details—and even the existence—of a Renaissance slide trumpet is a matter of debate among scholars. While there is documentation (written and artistic) of its existence, there is also conjecture that its slide would have been impractical.[17]

Some slide trumpet designs saw use in England in the 18th century.[18]

The pocket trumpet is a compact B♭ trumpet. The bell is usually smaller than a standard trumpet bell and the tubing is more tightly wound to reduce the instrument size without reducing the total tube length. Its design is not standardized, and the quality of various models varies greatly. It can have a unique warm sound and voice-like articulation. Since many pocket trumpet models suffer from poor design as well as poor manufacturing, the intonation, tone color and dynamic range of such instruments are severely hindered. Professional-standard instruments are, however, available. While they are not a substitute for the full-sized instrument, they can be useful in certain contexts. The jazz musician Don Cherry was renowned for his playing of the pocket instrument.

The herald trumpet has an elongated bell extending far in front of the player, allowing a standard length of tubing from which a flag may be hung; the instrument is mostly used for ceremonial events such as parades and fanfares.

David Monette designed the flumpet in 1989 for jazz musician Art Farmer. It is a hybrid of a trumpet and a flugelhorn, pitched in B♭ and using three piston valves.[19]

Other variations include rotary-valve, or German, trumpets (which are commonly used in professional German and Austrian orchestras), alto and Baroque trumpets, and the Vienna valve trumpet (primarily used in Viennese brass ensembles and orchestras such as the Vienna Philharmonic and Mnozil Brass).

The trumpet is often confused with its close relative the cornet, which has a more conical tubing shape compared to the trumpet's more cylindrical tube. This, along with additional bends in the cornet's tubing, gives the cornet a slightly mellower tone, but the instruments are otherwise nearly identical. They have the same length of tubing and, therefore, the same pitch, so music written for cornet and trumpet is interchangeable. Another relative, the flugelhorn, has tubing that is even more conical than that of the cornet, and an even richer tone. It is sometimes augmented with a fourth valve to improve the intonation of some lower notes.

Playing

Fingering

On any modern trumpet, cornet, or flugelhorn, pressing the valves indicated by the numbers below produces the written notes shown. "Open" means all valves up, "1" means first valve, "1–2" means first and second valve simultaneously, and so on. The sounding pitch depends on the transposition of the instrument. Engaging the fourth valve, if present, usually drops any of these pitches by a perfect fourth as well. Within each overtone series, the different pitches are attained by changing the embouchure. Standard fingerings above high C are the same as for the notes an octave below (C♯ is 1–2, D is 1, etc.).

Each overtone series on the trumpet begins with the first overtone—the fundamental of each overtone series cannot be produced except as a pedal tone. Notes in parentheses are the sixth overtone, representing a pitch with a frequency of seven times that of the fundamental; while this pitch is close to the note shown, it is flat relative to equal temperament, and use of those fingerings is generally avoided.

The fingering schema arises from the length of each valve's tubing (a longer tube produces a lower pitch). Valve "1" increases the tubing length enough to lower the pitch by one whole step, valve "2" by one half step, and valve "3" by one and a half steps.[20] This scheme and the nature of the overtone series create the possibility of alternate fingerings for certain notes. For example, third-space "C" can be produced with no valves engaged (standard fingering) or with valves 2–3. Also, any note produced with 1–2 as its standard fingering can also be produced with valve 3 – each drops the pitch by 1+1⁄2 steps. Alternate fingerings may be used to improve facility in certain passages, or to aid in intonation. Extending the third valve slide when using the fingerings 1–3 or 1-2-3 further lowers the pitch slightly to improve intonation.[21]

Some of the partials of the harmonic series that a modern Bb trumpet can play for each combination of valves pressed are in tune with 12-tone equal temperament and some are not.

Mute

Various types of mutes can be placed in or over the bell, which decreases volume and changes timbre.[22] Of all brass instruments, trumpets have the widest selection of mutes: common mutes include the straight mute, cup mute, harmon mute (wah-wah or wow-wow mute, among other names[23]), plunger, bucket mute, and practice mute.[24] When the type of mute is not specified, players generally use a straight mute, the most common type.[23] Jazz, commercial, and show band musicians often use a wider range of mutes than their classical counterparts,[22] and many mutes were invented for jazz orchestrators.[25]

Mutes can be made of many materials, including fiberglass, plastic, cardboard, metal, and "stone lining", a trade name of the Humes & Berg company.[26] They are often held in place with cork.[22][27] To better keep the mute in place, players sometimes dampen the cork by blowing warm, moist air on it. [22]

The straight mute is conical and constructed of either metal (usually aluminum[23])—which produces a bright, piercing sound—or another material, which produces a darker, stuffier sound.[28][29] The cup mute is shaped like a straight mute with an additional, bell-facing cup at the end, and produces a darker tone than a straight mute.[30] The harmon mute is made of metal (usually aluminum or copper[23]) and consists of a "stem" inserted into a large chamber.[30] The stem can be extended or removed to produce different timbres, and waving one's hand in front of the mute produces a "wah-wah" sound, hence the mute's colloquial name.[30]

Range

Using standard technique, the lowest note is the written F♯ below middle C. There is no actual limit to how high brass instruments can play, but fingering charts generally go up to the high C two octaves above middle C. Several trumpeters have achieved fame for their proficiency in the extreme high register, among them Maynard Ferguson, Cat Anderson, Dizzy Gillespie, Doc Severinsen, and more recently Wayne Bergeron, Thomas Gansch, James Morrison, Jon Faddis and Arturo Sandoval. It is also possible to produce pedal tones below the low F♯, which is a device occasionally employed in the contemporary repertoire for the instrument.

Extended technique

Contemporary music for the trumpet makes wide uses of extended trumpet techniques.

Flutter tonguing: The trumpeter rolls the tip of the tongue (as if rolling an "R" in Spanish) to produce a 'growling like' tone. This technique is widely employed by composers like Berio and Stockhausen.

Growling: Simultaneously playing tone and using the back of the tongue to vibrate the uvula, creating a distinct sound. Most trumpet players will use a plunger with this technique to achieve a particular sound heard in a lot of Chicago Jazz of the 1950s.

Double tonguing: The player articulates using the syllables ta-ka ta-ka ta-ka.

Triple tonguing: The same as double tonguing, but with the syllables ta-ta-ka ta-ta-ka ta-ta-ka.

Doodle tongue: The trumpeter tongues as if saying the word doodle. This is a very faint tonguing similar in sound to a valve tremolo.

Glissando: Trumpeters can slide between notes by depressing the valves halfway and changing the lip tension. Modern repertoire makes extensive use of this technique.

Vibrato: It is often regulated in contemporary repertoire through specific notation. Composers can call for everything from fast, slow or no vibrato to actual rhythmic patterns played with vibrato.

Pedal tone: Composers have written notes as low as two-and-a-half octaves below the low F♯ at the bottom of the standard range. Extreme low pedals are produced by slipping the lower lip out of the mouthpiece. Claude Gordon assigned pedals as part of his trumpet practice routines, that were a systematic expansion on his lessons with Herbert L. Clarke. The technique was pioneered by Bohumir Kryl.[31]

Microtones: Composers such as Scelsi and Stockhausen have made wide use of the trumpet's ability to play microtonally. Some instruments feature a fourth valve that provides a quarter-tone step between each note. The jazz musician Ibrahim Maalouf uses such a trumpet, invented by his father to make it possible to play Arab maqams.

Valve tremolo: Many notes on the trumpet can be played in several different valve combinations. By alternating between valve combinations on the same note, a tremolo effect can be created. Berio makes extended use of this technique in his Sequenza X.

Noises: By hissing, clicking, or breathing through the instrument, the trumpet can be made to resonate in ways that do not sound at all like a trumpet. Noises may require amplification.

Preparation: Composers have called for trumpeters to play under water, or with certain slides removed. It is increasingly common for composers to specify all sorts of preparations for trumpet. Extreme preparations involve alternate constructions, such as double bells and extra valves.

Split tone: Trumpeters can produce more than one tone simultaneously by vibrating the two lips at different speeds. The interval produced is usually an octave or a fifth.

Lip-trill or shake: Also known as "lip-slurs". By rapidly varying air speed, but not changing the depressed valves, the pitch can vary quickly between adjacent harmonic partials. Shakes and lip-trills can vary in speed, and in the distance between the partials. However, lip-trills and shakes usually involve the next partial up from the written note.

Multi-phonics: Playing a note and "humming" a different note simultaneously. For example, sustaining a middle C and humming a major 3rd "E" at the same time.

Circular breathing: A technique wind players use to produce uninterrupted tone, without pauses for breaths. The player puffs up the cheeks, storing air, then breathes in rapidly through the nose while using the cheeks to continue pushing air outwards.

Instruction and method books

One trumpet method is Jean-Baptiste Arban's Complete Conservatory Method for Trumpet (Cornet).[32] Other well-known method books include Technical Studies by Herbert L. Clarke,[33] Grand Method by Louis Saint-Jacome, Daily Drills and Technical Studies by Max Schlossberg, and methods by Ernest S. Williams, Claude Gordon, Charles Colin, James Stamp, and Louis Davidson.[34] A common method book for beginners is the Walter Beeler's Method for the Cornet, and there have been several instruction books written by virtuoso Allen Vizzutti.[35] Merri Franquin wrote a Complete Method for Modern Trumpet,[36] which fell into obscurity for much of the twentieth century until public endorsements by Maurice André revived interest in this work.[37]

Players

In early jazz, Louis Armstrong was well known for his virtuosity and his improvisations on the Hot Five and Hot Seven recordings, and his switch from cornet to trumpet is often cited as heralding the trumpet's dominance over the cornet in jazz.[3][38] Dizzy Gillespie was a gifted improviser with an extremely high (but musical) range, building on the style of Roy Eldridge but adding new layers of harmonic complexity. Gillespie had an enormous impact on virtually every subsequent trumpeter, both by the example of his playing and as a mentor to younger musicians. Miles Davis is widely considered one of the most influential musicians of the 20th century—his style was distinctive and widely imitated. Davis' phrasing and sense of space in his solos have been models for generations of jazz musicians.[39] Cat Anderson was a trumpet player who was known for the ability to play extremely high with an even more extreme volume, who played with Duke Ellington's Big Band. Maynard Ferguson came to prominence playing in Stan Kenton's orchestra, before forming his own band in 1957. He was noted for being able to play accurately in a remarkably high register.[40]

Musical pieces

Solos

Anton Weidinger developed in the 1790s the first successful keyed trumpet, capable of playing all the chromatic notes in its range. Joseph Haydn's Trumpet Concerto was written for him in 1796 and startled contemporary audiences by its novelty,[41] a fact shown off by some stepwise melodies played low in the instrument's range.

In art

The Last Judgment (workshop of Hieronymus Bosch), c. 1500–1510

The Last Judgment (workshop of Hieronymus Bosch), c. 1500–1510 Trumpet-Player in front of a Banquet, Gerrit Dou, c. 1660–1665

Trumpet-Player in front of a Banquet, Gerrit Dou, c. 1660–1665 Illustration for The Trumpeter Taken Prisoner from Baby's Own Aesop, a children's edition of Aesop's fables

Illustration for The Trumpeter Taken Prisoner from Baby's Own Aesop, a children's edition of Aesop's fables Louis Armstrong statue in Algiers, New Orleans

Louis Armstrong statue in Algiers, New Orleans Miles Davis statue in Kielce, Poland

Miles Davis statue in Kielce, Poland

See also

- Herald and Trumpet contest

- Compositions for trumpet

- Birch trumpet

- Muted trumpet

- Wind controller

References

Notes

- "History of the Trumpet (According to the New Harvard Dictionary of Music)". petrouska.com. Archived from the original on 8 June 2008. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- "Brass Family of Instruments: What instruments are in the Brass Family?". www.orsymphony.org. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- Koehler 2013

- "Trumpet". www.etymonline.com. Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- "Trump". www.etymonline.com. Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- Edward Tarr, The Trumpet (Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press, 1988), 20–30.

- "Trumpet with a swelling decorated with a human head," Musée du Louvre

- "History of the Trumpet | Pops' Trumpet College". Bbtrumpet.com. 8 November 2017. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- Berrin, Katherine & Larco Museum. The Spirit of Ancient Peru:Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1997.

- "Chicago Symphony Orchestra – Glossary – Brass instruments". cso.org. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- John Wallace and Alexander McGrattan, The Trumpet, Yale Musical Instrument Series (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2011): 239. ISBN 978-0-300-11230-6.

- Berlioz, Hector (1844). Treatise on modern Instrumentation and Orchestration. Edwin F. Kalmus, NY, 1948.

- "Trumpet, Brass Instrument". dsokids.com. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- Bloch, Dr. Colin (August 1978). "The Bell-Tuned Trumpet". Archived from the original on 25 December 2008. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- D. J. Blaikley, "How a Trumpet Is Made. I. The Natural Trumpet and Horn", The Musical Times, 1 January 1910, p. 15.

- P-trumpet

- "IngentaConnect More about Renaissance slide trumpets: fact or fiction?". ingentaconnect.com. Archived from the original on 22 September 2012. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- Lessen, Martin (1997). "JSTOR: Notes, Second Series". Notes. 54 (2): 484–485. doi:10.2307/899543. JSTOR 899543.

- Koehler, Elisa (2014). Fanfares and Finesse: A Performer's Guide to Trumpet History and Literature. Indiana University Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-253-01179-4. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- Pagliaro, Michael J. (2016). The Brass Instrument Owner's Handbook. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 37–39. ISBN 978-1-4422-6862-3. OCLC 946032345.

- Ely, Mark C.; Van Deuren, Amy E. (2009). Wind Talk for Brass: A Practical Guide to Understanding and Teaching Brass Instruments. Amy E. Van Deuren. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 8–12. ISBN 978-0-19-971631-9. OCLC 472461178.

- Ely 2009, p. 109.

- Ely 2009, p. 111.

- For the "widest selection of mutes", see Sevsay 2013, p. 125.

- For the list of common mutes, see Ely 2009, p. 109.

- Boyden, David D.; Bevan, Clifford; Page, Janet K. (20 January 2001). "Mute". Grove Music Online. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.19478. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- For the list of materials, see Ely 2009, p. 109.

- For the origin of "stonelined mutes", see Koehler 2013, p. 173.

- Sevsay 2013, p. 125.

- Sevsay 2013, p. 125: "plastic (fiberglass): not as forceful as the metal mute, a bit darker in color, but still penetrating"

- Koehler 2013, p. 173.

- Sevsay 2013, p. 126.

- Joseph Wheeler, "Review: Edward H. Tarr, Die Trompete" The Galpin Society Journal, Vol. 31, May 1978, p. 167.

- Arban, Jean-Baptiste (1894, 1936, 1982). Arban's Complete Conservatory Method for trumpet. Carl Fischer, Inc. ISBN 0-8258-0385-3.

- Herbert L. Clarke (1984). Technical Studies for the Cornet, C. Carl Fischer, Inc. ISBN 0-8258-0158-3.

- Colin, Charles and Advanced Lip Flexibilities.

- "Allen Vizzutti Official Website". www.vizzutti.com. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- Franquin, Merri (2016) [1908]. Quinlan, Timothy (ed.). "Complete Method for Modern Trumpet". qpress.ca. Translated by Jackson, Susie.

- Shamu, Geoffrey. "Merri Franquin and His Contribution to the Art of Trumpet Playing" (PDF). p. 20. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- West, Michael J. (3 November 2017). "The Cornet: Secrets of the Little Big Horn". JazzTimes.com. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- "Miles Davis, Trumpeter, Dies; Jazz Genius, 65, Defined Cool". nytimes.com. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- "Ferguson, Maynard". Encyclopedia of Music in Canada. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2 January 2008.

- Keith Anderson, liner notes for Naxos CD 8.550243, Famous Trumpet Concertos, "Haydn's concerto, written for Weidinger in 1796, must have . At the first performance of the new concerto in Vienna in 1800 a trumpet melody was heard in a lower register than had hitherto been practicable."

Bibliography

- Barclay, R. L. (1992). The art of the trumpet-maker: the materials, tools, and techniques of the seventeenth [sic] and eighteenth centuries in Nuremberg. Oxford [England]: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-816223-5.

- Bate, Philip (1978). The trumpet and trombone : an outline of their history, development, and construction (2nd ed.). London: E. Benn. ISBN 0-393-02129-7.

- Brownlow, James Arthur (1996). The last trumpet: a history of the English slide trumpet. Stuyvesant, N.Y.: Pendragon Press. ISBN 0-945193-81-5.

- Campos, Frank Gabriel (2005). Trumpet technique. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-516692-2.

- Cassone, Gabriele (2009). The trumpet book (1st ed.). Varese, Italy: Zecchini. ISBN 978-88-87203-80-6.

- Ely, Mark C. (2009). Wind talk for brass: a practical guide to understanding and teaching brass instruments. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-532924-7.

- English, Betty Lou (1980). You can't be timid with a trumpet: notes from the orchestra (1st ed.). New York: Lothrop, Lee & Shepard Books. ISBN 0-688-41963-1.

- Koehler, Elisa (2013). Dictionary for the modern trumpet player. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-8658-2.

- Sherman, Roger (1979). The trumpeter's handbook: a comprehensive guide to playing and teaching the trumpet. Athens, Ohio: Accura Music. ISBN 0-918194-02-4.

- Sevsay, Ertuğrul (2013). The Cambridge guide to orchestration. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-1-107-02516-5.

- Smithers, Don L. (1973). The music and history of the baroque trumpet before 1721 (1st ed.). Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0-8156-2157-4.

External links

The dictionary definition of trumpet at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of trumpet at Wiktionary- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). 1911.

- International Trumpet Guild, international trumpet players' association with online library of scholarly journal back issues, news, jobs and other trumpet resources.

- Trumpet Playing Articles by Jeff Purtle, protege of Claude Gordon

- Trumpet Players' International Network is the oldest and largest email list with members from all parts of world.

- Jay Lichtmann's trumpet studies Scales and technical trumpet studies.

- 60+ Trumpet and Teaching Videos Flash media TV of 60 trumpet and teaching videos by Clint Pops McLaughlin.