Uterine fibroid

Uterine fibroids, also known as uterine leiomyomas or fibroids, are benign smooth muscle tumors of the uterus.[1] Most women[note 1] with fibroids have no symptoms while others may have painful or heavy periods.[1] If large enough, they may push on the bladder, causing a frequent need to urinate.[1] They may also cause pain during penetrative sex or lower back pain.[1][3] A woman can have one uterine fibroid or many.[1] Occasionally, fibroids may make it difficult to become pregnant, although this is uncommon.[1]

| Uterine fibroids | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Uterine leiomyoma, uterine myoma, myoma, fibromyoma, fibroleiomyoma |

| |

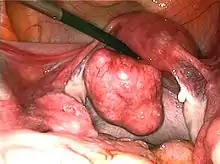

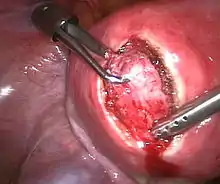

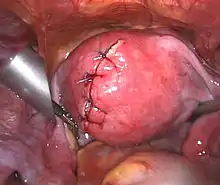

| Uterine fibroids as seen during laparoscopic surgery | |

| Specialty | Gynecology |

| Symptoms | Painful or heavy periods[1] |

| Complications | Infertility[1] |

| Usual onset | Middle and later reproductive years[1] |

| Causes | Unknown[1] |

| Risk factors | Family history, obesity, eating red meat[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Pelvic examination, medical imaging[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Leiomyosarcoma, pregnancy, ovarian cyst, ovarian cancer[2] |

| Treatment | Medications, surgery, uterine artery embolization[1] |

| Medication | Ibuprofen, paracetamol (acetaminophen), iron supplements, gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist[1] |

| Prognosis | Improve after menopause[1] |

| Frequency | ~50% of women by age 50[1] |

The exact cause of uterine fibroids is unclear.[1] However, fibroids run in families and appear to be partly determined by hormone levels.[1] Risk factors include obesity and eating red meat.[1] Diagnosis can be performed by pelvic examination or medical imaging.[1]

Treatment is typically not needed if there are no symptoms.[1] NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen, may help with pain and bleeding while paracetamol (acetaminophen) may help with pain.[1][4] Iron supplements may be needed in those with heavy periods.[1] Medications of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist class may decrease the size of the fibroids but are expensive and associated with side effects.[1] If greater symptoms are present, surgery to remove the fibroid or uterus may help.[1] Uterine artery embolization may also help.[1] Cancerous versions of fibroids are very rare and are known as leiomyosarcomas.[1] They do not appear to develop from benign fibroids.[1]

About 20% to 80% of women develop fibroids by the age of 50.[1] In 2013, it was estimated that 171 million women were affected worldwide.[5] They are typically found during the middle and later reproductive years.[1] After menopause, they usually decrease in size.[1] In the United States, uterine fibroids are a common reason for surgical removal of the uterus.[6]

Signs and symptoms

Some women with uterine fibroids do not have symptoms. Abdominal pain, anemia and increased bleeding can indicate the presence of fibroids.[7] There may also be pain during intercourse (penetration), depending on the location of the fibroid. During pregnancy, they may also be the cause of miscarriage,[8] bleeding, premature labor, or interference with the position of the fetus.[9] A uterine fibroid can cause rectal pressure. The abdomen can grow larger mimicking the appearance of pregnancy.[1] Some large fibroids can extend out through the cervix and vagina.[7]

While fibroids are common, they are not a typical cause for infertility, accounting for about 3% of reasons why a woman may not be able to have a child.[10] The majority of women with uterine fibroids will have normal pregnancy outcomes.[11][12] In cases of intercurrent uterine fibroids in infertility, a fibroid is typically located in a submucosal position and it is thought that this location may interfere with the function of the lining and the ability of the embryo to implant.[10]

Risk factors

Some risk factors associated with the development of uterine fibroids are modifiable.[13] Fibroids are more common in obese women.[14] Fibroids are dependent on estrogen and progesterone to grow and therefore relevant only during the reproductive years.

Diet

Diets high in fruits and vegetables tend to lower the risk of developing fibroids.[13] Fibers, vitamin A, C and E, phytoestrogens, carotenoids, meat, fish, and dairy products are of unclear effect.[13] Normal dietary levels of vitamin D may reduce the risk of developing fibroids.[13]

Genetics

Fifty percent of uterine fibroids demonstrate a genetic abnormality. Often a translocation is found on some chromosomes.[7] Fibroids are partly genetic. If a mother had fibroids, risk in the daughter is about three times higher than average.[15] Black women have a 3–9 times increased chance of developing uterine fibroids than white women.[16] Only a few specific genes or cytogenetic deviations are associated with fibroids.[17] 80–85% of fibroids have a mutation in the mediator complex subunit 12 (MED12) gene.[18][19]

Familial leiomyomata

A syndrome (Reed's syndrome) that causes uterine leiomyomata along with cutaneous leiomyomata and renal cell cancer has been reported.[20][21][22] This is associated with a mutation in the gene that produces the enzyme fumarate hydratase, located on the long arm of chromosome 1 (1q42.3-43). Inheritance is autosomal dominant.

Pathophysiology

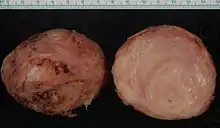

Fibroids are a type of uterine leiomyoma. Fibroids grossly appear as round, well circumscribed (but not encapsulated), solid nodules that are white or tan, and show whorled appearance on histological section. The size varies, from microscopic to lesions of considerable size. Typically lesions the size of a grapefruit or bigger are felt by the patient herself through the abdominal wall.[1]

Microscopically, tumor cells resemble normal cells (elongated, spindle-shaped, with a cigar-shaped nucleus) and form bundles with different directions (whorled). These cells are uniform in size and shape, with scarce mitoses. There are three benign variants: bizarre (atypical); cellular; and mitotically active.

The appearance of prominent nucleoli with peri-nucleolar halos should alert the pathologist to investigate the possibility of the extremely rare hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (Reed) syndrome.[23]

Location and classification

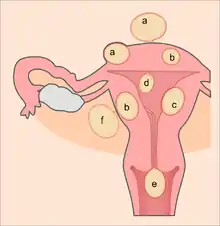

Growth and location are the main factors that determine if a fibroid leads to symptoms and problems.[6] A small lesion can be symptomatic if located within the uterine cavity while a large lesion on the outside of the uterus may go unnoticed. Different locations are classified as follows:

- Intramural fibroids are located within the muscular wall of the uterus. Unless they are large, they may be asymptomatic. Intramural fibroids begin as small nodules in the muscular wall of the uterus. With time, intramural fibroids may expand inwards, causing distortion and elongation of the uterine cavity.

- Subserosal fibroids are located on the surface of the uterus. They can also grow outward from the surface and remain attached by a small piece of tissue and then are called pedunculated fibroids.[1]

- Submucosal fibroids are most common type, located in the muscle beneath the endometrium of the uterus and distort the uterine cavity; even small lesions in this location may lead to bleeding and infertility. A pedunculated lesion within the cavity is termed an intracavitary fibroid and can be passed through the cervix.

- Cervical fibroids are located in the wall of the cervix (neck of the uterus). Rarely, fibroids are found in the supporting structures (round ligament, broad ligament, or uterosacral ligament) of the uterus that also contain smooth muscle tissue.

Fibroids may be single or multiple. Most fibroids start in the muscular wall of the uterus. With further growth, some lesions may develop towards the outside of the uterus or towards the internal cavity. Secondary changes that may develop within fibroids are hemorrhage, necrosis, calcification, and cystic changes. They tend to calcify after menopause.[24]

If the uterus contains too many to count, it is referred to as diffuse uterine leiomyomatosis.

Extrauterine fibroids of uterine origin, metastatic fibroids

Fibroids of uterine origin located in other parts of the body, sometimes also called parasitic myomas have been historically extremely rare, but are now diagnosed with increasing frequency. They may be related or identical to metastasizing leiomyoma.

They are in most cases still hormone dependent but may cause life-threatening complications when they appear in distant organs. Some sources suggest that a substantial share of the cases may be late complications of surgeries such as myomectomy or hysterectomy. Particularly laparoscopic myomectomy using a morcellator has been associated with an increased risk of this complication.[25][26][27]

There are a number of rare conditions in which fibroids metastasize. They still grow in a benign fashion, but can be dangerous depending on their location.[28]

- In leiomyoma with vascular invasion, an ordinary-appearing fibroid invades into a vessel but there is no risk of recurrence.

- In intravenous leiomyomatosis, leiomyomata grow in veins with uterine fibroids as their source. Involvement of the heart can be fatal.

- In benign metastasizing leiomyoma, leiomyomata grow in more distant sites such as the lungs and lymph nodes. The source is not entirely clear. Pulmonary involvement can be fatal.

- In disseminated intraperitoneal leiomyomatosis, leiomyomata grow diffusely on the peritoneal and omental surfaces, with uterine fibroids as their source. This can simulate a malignant tumor but behaves benignly.

Pathogenesis

Fibroids are monoclonal tumors and approximately 40–50% show karyotypically detectable chromosomal abnormalities. When multiple fibroids are present they frequently have unrelated genetic defects. Specific mutations of the MED12 protein have been noted in 70 percent of fibroids.[29]

The exact cause of fibroids is not clearly understood, but the current working hypothesis is that genetic predispositions, prenatal hormone exposure and the effects of hormones, growth factors and xenoestrogens cause fibroid growth. Known risk factors are African descent, obesity, polycystic ovary syndrome, diabetes, hypertension, and never having given birth.[30]

It is believed that estrogen and progesterone have a mitogenic effect on leiomyoma cells and also act by influencing (directly and indirectly) a large number of growth factors, cytokines and apoptotic factors as well as other hormones. Furthermore, the actions of estrogen and progesterone are modulated by the cross-talk between estrogen, progesterone and prolactin signaling which controls the expression of the respective nuclear receptors. It is believed that estrogen promotes growth by up-regulating IGF-1, EGFR, TGF-beta1, TGF-beta3 and PDGF, and promotes aberrant survival of leiomyoma cells by down-regulating p53, increasing expression of the anti-apoptotic factor PCP4 and antagonizing PPAR-gamma signaling. Progesterone is thought to promote the growth of leiomyoma through up-regulating EGF, TGF-beta1 and TGF-beta3, and promotes survival through up-regulating Bcl-2 expression and down-regulating TNF-alpha. Progesterone is believed to counteract growth by downregulating IGF-1.[31] Expression of transforming growth interacting factor (TGIF) is increased in leiomyoma compared with myometrium.[32] TGIF is a potential repressor of TGF-β pathways in myometrial cells.[32]

Aromatase and 17beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase are aberrantly expressed in fibroids, indicating that fibroids can convert circulating androstenedione into estradiol.[33] Similar mechanism of action has been elucidated in endometriosis and other endometrial diseases.[34] Aromatase inhibitors are currently considered for treatment, at certain doses they would completely inhibit estrogen production in the fibroid while not largely affecting ovarian production of estrogen (and thus systemic levels of it). Aromatase overexpression is particularly pronounced in African-American women.[35]

Genetic and hereditary causes are being considered and several epidemiologic findings indicate considerable genetic influence especially for early onset cases. First degree relatives have a 2.5-fold risk, and nearly 6-fold risk when considering early onset cases. Monozygotic twins have double concordance rate for hysterectomy compared to dizygotic twins.[36]

Expansion of uterine fibroids occurs by a slow rate of cell proliferation combined with the production of copious amounts of extracellular matrix.[35]

A small population of the cells in a uterine fibroid have properties of stem cells or progenitor cells, and contribute significantly to ovarian steroid-dependent growth of fibroids. These stem-progenitor cells are deficient in estrogen receptor α and progesterone receptor and instead rely on substantially higher levels of these receptors in surrounding differentiated cells to mediate estrogen and progesterone actions via paracrine signaling.[35]

Diagnosis

Physical examination and ultrasound are sufficient for diagnosing uterine fibroids in the majority of patients. When ultrasound findings are inconclusive, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be able to confirm the diagnosis of uterine fibroids in most cases. In addition, MRI can identify benign uterine fibroids with atypical imaging features and fibroids with variant growth patterns. MRI can also identify other uterine (e.g. adenomyosis, endometrial polyps, endometrial cancer) and extrauterine (e.g. benign and malignant ovarian tumors, endometriosis) disorders that may mimic the appearance of uterine fibroids and/or contribute to the patient's symptoms.[37] However, a small proportion of uterine fibroids can mimic other malignant uterine tumors (e.g. leiomyosarcoma) on all available imaging modalities (e.g. ultrasound, CT, MRI and PET-CT).[37]

Malignant tumors of the uterine wall (e.g. leiomyosarcoma) are very rare. Findings suggestive of a malignant uterine tumor rather than a benign fibroid include, fast or unexpected growth (particularly after menopause), interruption/effacement of the endometrial stripe, lymph node enlargement, invasion of adjacent organs and metastases to distant organs (e.g. lung). MRI findings suggestive of a malignancy include nodular/ill-circumscribed tumor margins, intermediate/high T2-weighted signal intensity of the solid tumor components, regions with high signal T1-weighted sequences in keeping with subacute hemorrhage, fine/wispy enhancement of the solid parts of the tumor, and restricted diffusion on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI).[37] A biopsy is rarely performed and if performed, is rarely diagnostic. Should there be an uncertain diagnosis after ultrasounds and MRI imaging, surgery is generally indicated.[38]

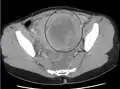

A very large (9 cm) fibroid of the uterus which is causing pelvic congestion syndrome as seen on CT

A very large (9 cm) fibroid of the uterus which is causing pelvic congestion syndrome as seen on CT A very large (9 cm) fibroid of the uterus which is causing pelvic congestion syndrome as seen on ultrasound

A very large (9 cm) fibroid of the uterus which is causing pelvic congestion syndrome as seen on ultrasound A relatively large submucosal leiomyoma; it fills out the major part of the endometrial cavity.

A relatively large submucosal leiomyoma; it fills out the major part of the endometrial cavity. A small uterine fibroid seen within the wall of the myometrium on a cross-sectional ultrasound view

A small uterine fibroid seen within the wall of the myometrium on a cross-sectional ultrasound view Two calcified fibroids (in the uterus)

Two calcified fibroids (in the uterus) A subserosal uterine fibroid with a diameter of 5 centimeters

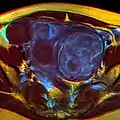

A subserosal uterine fibroid with a diameter of 5 centimeters MRI image with multiple uterine leiomiyomas

MRI image with multiple uterine leiomiyomas Giant leiomiyomas almost filling the abdomen

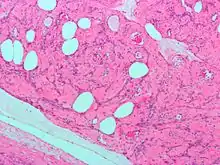

Giant leiomiyomas almost filling the abdomen Histopathology of uterine fibroids typically show smooth muscle in a whorled (fascicular) pattern.[39]

Histopathology of uterine fibroids typically show smooth muscle in a whorled (fascicular) pattern.[39].jpg.webp) This variant of Van Gieson's stain distinguishes muscle (yellow) from connective tissue (red).

This variant of Van Gieson's stain distinguishes muscle (yellow) from connective tissue (red).

Coexisting disorders

Fibroids that lead to heavy vaginal bleeding lead to anemia and iron deficiency. Due to pressure effects gastrointestinal problems such as constipation and bloatedness are possible. Compression of the ureter may lead to hydronephrosis. Fibroids may also present alongside endometriosis, which itself may cause infertility. Adenomyosis may be mistaken for or coexist with fibroids.

In very rare cases, malignant (cancerous) growths, leiomyosarcoma, of the myometrium can develop.[40] In extremely rare cases uterine fibroids may present as part or early symptom of the hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer syndrome.

Treatment

Most fibroids do not require treatment unless they are causing symptoms. After menopause, fibroids shrink, and it is unusual for them to cause problems.

Symptomatic uterine fibroids can be treated by:

- medication to control symptoms (i.e., symptomatic management)

- medication aimed at shrinking tumors

- ultrasound fibroid destruction

- myomectomy or radiofrequency ablation

- hysterectomy

- uterine artery embolization

In those who have symptoms, uterine artery embolization and surgical options have similar outcomes with respect to satisfaction.[41]

Medication

A number of medications may be used to control symptoms. NSAIDs can be used to reduce painful menstrual periods. Oral contraceptive pills may be prescribed to reduce uterine bleeding and cramps.[10] Anemia may be treated with iron supplementation.

Levonorgestrel intrauterine devices are effective in limiting menstrual blood flow and improving other symptoms. Side effects are typically few as the levonorgestrel (a progestin) is released in low concentration locally.[42] While most levongestrel-IUD studies concentrated on treatment of women without fibroids a few reported good results specifically for women with fibroids including a substantial regression of fibroids.[43][44]

Cabergoline in a moderate and well-tolerated dose has been shown in two studies to shrink fibroids effectively. The mechanism of action responsible for how cabergoline shrinks fibroids is unclear.[43]

Ulipristal acetate is a synthetic selective progesterone receptor modulator (SPRM) that has tentative evidence to support its use for presurgical treatment of fibroids with low side-effects.[45] Long-term UPA-treated fibroids have shown volume reduction of about 70%.[46] In some cases UPA alone is used to relieve symptoms without surgery,[47] and to allow successful pregnancies without fibroid regrowth.[48] Indeed, in the tumor cells, the molecule blocks the cell proliferation, induces their apoptosis[49][50] and stimulates the remodeling of the extensive fibrosis by matrix metalloproteinases,[51] hence explaining the long-term benefit.[52] Yet, due to some rare but severe hepatic injuries after UPA treatment, the licence was suspended in 2020 in the EU[53] and voluntary removed in Canada.[54]

Danazol is an effective treatment to shrink fibroids and control symptoms. Its use is limited by unpleasant side effects. Mechanism of action is thought to be antiestrogenic effects. Recent experience indicates that safety and side effect profile can be improved by more cautious dosing.[43]

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs cause temporary regression of fibroids by decreasing estrogen levels. Because of the limitations and side effects of this medication, it is rarely recommended other than for preoperative use to shrink the size of the fibroids and uterus before surgery. It is typically used for a maximum of six months or less because after longer use they could cause osteoporosis and other typically postmenopausal complications. The main side effects are transient postmenopausal symptoms. In many cases the fibroids will regrow after cessation of treatment, however, significant benefits may persist for much longer in some cases. Several variations are possible, such as GnRH agonists with add-back regimens intended to decrease the adverse effects of estrogen deficiency. Several add-back regimes are possible, tibolone, raloxifene, progestogens alone, estrogen alone, and combined estrogens and progestogens.[43]

Progesterone antagonists such as mifepristone have been tested, there is evidence that it relieves some symptoms and improves quality of life but because of adverse histological changes that have been observed in several trials it can not be currently recommended outside of research setting.[55][56] Fibroid growth has recurred after antiprogestin treatment was stopped.[35]

Aromatase inhibitors have been used experimentally to reduce fibroids. The effect is believed to be due partially by lowering systemic estrogen levels and partially by inhibiting locally overexpressed aromatase in fibroids.[43] However, fibroid growth has recurred after treatment was stopped.[35] Experience from experimental aromatase inhibitor treatment of endometriosis indicates that aromatase inhibitors might be particularly useful in combination with a progestogenic ovulation inhibitor.

Uterine artery

Uterine artery embolization (UAE) is a noninvasive procedure that blocks blood flow to fibroids, causing them to shrink.[57] Long-term outcomes with respect to how happy people are with the procedure are similar to that of surgery.[58] There is tentative evidence that traditional surgery may result in better fertility.[58] One review found that UAE doubles the future risk of miscarriage.[59] UAE also appears to require more repeat procedures than if surgery was done initially.[58] A person will usually recover from the procedure within a few days.

Uterine artery ligation, sometimes also laparoscopic occlusion of uterine arteries are minimally invasive methods to limit blood supply of the uterus by a small surgery that can be performed transvaginally or laparoscopically. The principal mechanism of action may be similar like in UAE but is easier to perform and fewer side effects are expected.[60][61]

The 2016 NICE (National Institute of Clinical Excellence – the non governmental public body that publishes guidelines in the use of health technologies and good clinical practice in the United Kingdom) guidelines state UAE/UFE can be offered to women with symptomatic fibroids (fibroids being usually >30mm in size). Women should be informed that UAE and myomectomy (the surgical removal of fibroids) may potentially allow them to retain their fertility.[62]

Myomectomy

Myomectomy is a surgery to remove one or more fibroids. It is usually recommended when more conservative treatment options fail for women who want fertility preserving surgery or who want to retain the uterus.[63]

There are three types of myomectomy:

- In a hysteroscopic myomectomy (also called transcervical resection), the fibroid can be removed by either the use of a resectoscope, an endoscopic instrument inserted through the vagina and cervix that can use high-frequency electrical energy to cut tissue, or a similar device.

- A laparoscopic myomectomy is done through a small incision near the navel. The physician uses a laparoscope and surgical instruments to remove the fibroids. Studies have suggested that laparoscopic myomectomy leads to lower morbidity rates and faster recovery than does laparotomic myomectomy.[64]

- A laparotomic myomectomy (also known as an open or abdominal myomectomy) is the most invasive surgical procedure to remove fibroids. The physician makes an incision in the abdominal wall and removes the fibroids from the uterus.

Laparoscopic myomectomy has less pain and shorter time in hospital than open surgery.[65]

Hysterectomy

Hysterectomy was the classical method of treating fibroids. Although it is now recommended only as last option, fibroids are still the leading cause of hysterectomies in the US.

Endometrial ablation

Endometrial ablation can be used if the fibroids are only within the uterus and not intramural and relatively small. High failure and recurrence rates are expected in the presence of larger or intramural fibroids.

Other procedures

Radiofrequency ablation is a minimally invasive treatments for fibroids.[66] In this technique the fibroid is shrunk by inserting a needle-like device into the fibroid through the abdomen and heating it with radio-frequency (RF) electrical energy to cause necrosis of cells. The treatment is a potential option for women who have fibroids, have completed child-bearing and want to avoid a hysterectomy.

Magnetic resonance guided focused ultrasound, is a non-invasive intervention (requiring no incision) that uses high intensity focused ultrasound waves to destroy tissue in combination with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which guides and monitors the treatment. During the procedure, delivery of focused ultrasound energy is guided and controlled using MR thermal imaging.[67] Patients who have symptomatic fibroids, who desire a non-invasive treatment option and who do not have contraindications for MRI are candidates for MRgFUS. About 60% of patients qualify. It is an outpatient procedure and takes one to three hours depending on the size of the fibroids. It is safe and about 75% effective.[68] Symptomatic improvement is sustained for two plus years.[69] Need for additional treatment varies from 16 to 20% and is largely dependent on the amount of fibroid that can be safely ablated; the higher the ablated volume, the lower the re-treatment rate.[70] There are currently no randomized trial between MRgFUS and UAE. A multi-center trial is underway to investigate the efficacy of MRgFUS vs. UAE.

Prognosis

About 1 out of 1,000 lesions are or become malignant, typically as a leiomyosarcoma on histology.[10] A sign that a lesion may be malignant is growth after menopause.[10] There is no consensus among pathologists regarding the transformation of leiomyoma into a sarcoma.

Metastasis

There are a number of rare conditions in which fibroids metastasize. They still grow in a benign fashion, but can be dangerous depending on their location.[28]

Epidemiology

About 20% to 80% of women develop fibroids by the age of 50.[13][1] Globally in 2013 it was estimated that 171 million women were affected.[5] They are typically found during the middle and later reproductive years.[1] After menopause they usually decrease in size.[1] Surgery to remove uterine fibroids occurs more frequently in women in "higher social classes".[13] Adolescents develop uterine fibroids much less frequently than older women.[7] Up to 50% of women with uterine fibroids have no symptoms. The prevalence of uterine fibroids among teenagers is 0.4%.[7]

Europe

The incidence of uterine fibroids in Europe is thought to be lower than the incidence in the US.[13]

United States

Eighty percent of African American women will develop benign uterine fibroid tumors by their late 40s, according to the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.[71] African American women are two to three times more likely to get fibroids than Caucasian women.[13][14][72] In African American women fibroids seem to occur at a younger age, grow more quickly, and are more likely to cause symptoms.[73] This leads to higher rates of surgery for African Americans, both myomectomy, and hysterectomy.[74] Increased risk of fibroids in African Americans causes them to fare worse in in-vitro fertility treatments and raises their risk of premature births and delivery by Caesarean section.[74]

It is unclear why fibroids are more common in African American women. Some studies suggest that black women who are obese and who have high blood pressure are more likely to have fibroids.[74] Other suggested causes include the tendency of African American women to consume food with less than the daily requirements for vitamin D.[13]

Related legislation

United States

The 2005 S.1289 bill was read twice and referred to the committee on Health, Labor, and Pensions but never passed for a Senate or House vote; the proposed Uterine Fibroid Research and Education Act of 2005 mentioned that $5 billion is spent annually on hysterectomy surgeries each year, which affect 22% of African Americans and 7% of Caucasian women. The bill also called for more funding for research and educational purposes. It also states that of the $28 billion issued to NIH, $5 million was allocated for uterine fibroids in 2004.[75]

Other animals

Uterine fibroids are rare in other mammals, although they have been observed in certain dogs and Baltic grey seals.[76]

Research

Selective progesterone receptor modulators, such as progenta, have been under investigation. Another selective progesterone receptor modulator asoprisnil is being tested with promising results as a possible use as a treatment for fibroids, intended to provide the advantages of progesterone antagonists without their adverse effects.[43] Low dietary intake of vitamin D is associated with the development of uterine fibroids.[13]

Notes

- Women make up the majority of people who can develop uterine fibroids, with trans men and non-binary people who were observed female at birth making up the remainder; a person must have a uterus to develop these fibroids.

References

- "Uterine fibroids fact sheet". Office on Women's Health. January 15, 2015. Archived from the original on 7 July 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- Ferri, Fred F. (2010). Ferri's differential diagnosis : a practical guide to the differential diagnosis of symptoms, signs, and clinical disorders (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Mosby. p. Chapter U. ISBN 978-0323076999.

- "Uterine Fibroids | Fibroids | MedlinePlus". Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- Kashani, BN; Centini, G; Morelli, SS; Weiss, G; Petraglia, F (July 2016). "Role of Medical Management for Uterine Leiomyomas". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 34: 85–103. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2015.11.016. hdl:11365/1031597. PMID 26796059.

- Global Burden of Disease Study 2013, Collaborators (5 June 2015). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 386 (9995): 743–800. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4. PMC 4561509. PMID 26063472.

{{cite journal}}:|first1=has generic name (help) - Wallach EE, Vlahos NF (August 2004). "Uterine myomas: an overview of development, clinical features, and management". Obstet Gynecol. 104 (2): 393–406. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000136079.62513.39. PMID 15292018. S2CID 45013410.

- Moroni, Rafael Mendes; Vieira, Carolina Sales; Ferriani, Rui Alberto; dos Reis, Rosana Maria; Nogueira, Antonio Alberto; Brito, Luiz Gustavo Oliveira (2015). "Presentation and treatment of uterine leiomyoma in adolescence: a systematic review". BMC Women's Health. 15 (1): 4. doi:10.1186/s12905-015-0162-9. ISSN 1472-6874. PMC 4308853. PMID 25609056.

- Metwally, Mostafa; Li, Tin-Chiu (2015). Reproductive Surgery in Assisted Conception. p. 107. ISBN 9781447149538.

- "Uterine Fibroids: Symptoms, Causes, Risk Factors & Treatment". Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved 2022-10-08.

- American Society of Reproductive Medicine Patient Booklet: Uterine Fibroids, 2003 Archived 2008-07-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Segars JH, Parrott EC, Nagel JD, Guo XC, Gao X, Birnbaum LS, Pinn VW, Dixon D (2014). "Proceedings from the Third National Institutes of Health International Congress on Advances in Uterine Leiomyoma Research: comprehensive review, conference summary and future recommendations". Human Reproduction Update. 20 (3): 309–333. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt058. PMC 3999378. PMID 24401287.

- Segars JH, Parrott EC, Nagel JD, Guo XC, Gao X, Birnbaum LS, Pinn VW, Dixon D (2014). "Proceedings from the Third National Institutes of Health International Congress on Advances in Uterine Leiomyoma Research: comprehensive review, conference summary and future recommendations". Hum. Reprod. Update. 20 (3): 309–33. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt058. PMC 3999378. PMID 24401287.

- Parazzini, Fabio; Di Martino, Mirella; Candiani, Massimo; Viganò, Paola (2015). "Dietary Components and Uterine Leiomyomas: A Review of Published Data". Nutrition and Cancer. 67 (4): 569–579. doi:10.1080/01635581.2015.1015746. ISSN 0163-5581. PMID 25826470. S2CID 35376265.

- Uterine Fibroids at Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy Professional Edition

- "Uterine fibroids fact sheet". womenshealth.gov. 2016-12-15. Archived from the original on 2016-02-09.

- Younas, Kinza; Hadoura, Essam; Majoko, Franz; Bunkheila, Adnan (January 2016). "A review of evidence-based management of uterine fibroids". The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist. 18 (1): 33–42. doi:10.1111/tog.12223.

- Medikare, V; Kandukuri, LR; Ananthapur, V; Deenadayal, M; Nallari, P (July 2011). "The genetic bases of uterine fibroids; a review". Journal of Reproduction & Infertility. 12 (3): 181–91. PMC 3719293. PMID 23926501.

- Kämpjärvi K, Park MJ, Mehine M, Kim NH, Clark AD, Bützow R, Böhling T, Böhm J, Mecklin JP, Järvinen H, Tomlinson IP, van der Spuy ZM, Sjöberg J, Boyer TG, Vahteristo P (Sep 2014). "Mutations in Exon 1 highlight the role of MED12 in uterine leiomyomas". Human Mutation. 35 (9): 1136–41. doi:10.1002/humu.22612. PMID 24980722. S2CID 13931280.

- Heinonen HR, Pasanen A, Heikinheimo O, Tanskanen T, Palin K, Tolvanen J, Vahteristo P, Sjöberg J, Pitkänen E, Bützow R, Mäkinen N, Aaltonen LA (2017). "Multiple clinical characteristics separate MED12-mutation-positive and -negative uterine leiomyomas". Sci Rep. 7 (1): 1015. Bibcode:2017NatSR...7.1015H. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-01199-0. PMC 5430741. PMID 28432313.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Tolvanen J, Uimari O, Ryynänen M, Aaltonen LA, Vahteristo P (2012). "Strong family history of uterine leiomyomatosis warrants fumarate hydratase mutation screening". Human Reproduction. 27 (6): 1865–9. doi:10.1093/humrep/des105. PMID 22473397.

- Toro JR, et al. (2003). "Mutations in the fumarate hydratase gene cause hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer in families in North America". Am J Hum Genet. 73 (1): 95–106. doi:10.1086/376435. PMC 1180594. PMID 12772087.

- "Reed syndrome". Archived from the original on 2012-02-24. Retrieved 2012-04-09.

- Garg K, Tickoo SK, Soslow RA, Reuter VE (2011). "Morphologic Features of Uterine Leiomyomas Associated with Hereditary Leiomyomatosis and Renal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome". The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 35 (8): 1235–1237. doi:10.1097/PAS.0b013e318223ca01. PMID 21753700. S2CID 1342593.

- Impey, Lawrence; Child, Tim (2016). Obstetrics and Gynaecology. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781119010807.

- Cucinella G, Granese R, Calagna G, Somigliana E, Perino A (2011). "Parasitic myomas after laparoscopic surgery: An emerging complication in the use of morcellator? Description of four cases". Fertility and Sterility. 96 (2): e90–e96. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.05.095. hdl:10447/77912. PMID 21719004.

- Nezhat C, Kho K (2010). "Iatrogenic Myomas: New Class of Myomas?". Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology. 17 (5): 544–550. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2010.04.004. PMID 20580324.

- "FDA Updated Assessment of The Use of Laparoscopic Power Morcellators to Treat Uterine Fibroids" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- Fletcher's Diagnostic Histopathology of Tumors (3rd ed.). pp. 692–4.

- Mäkinen N, Mehine M, Tolvanen J, Kaasinen E, Li Y, Lehtonen HJ, Gentile M, Yan J, Enge M, Taipale M, Aavikko M, Katainen R, Virolainen E, Böhling T, Koski TA, Launonen V, Sjöberg J, Taipale J, Vahteristo P, Aaltonen LA (2011). "MED12, the Mediator Complex Subunit 12 Gene, is Mutated at High Frequency in Uterine Leiomyomas". Science. 334 (6053): 252–255. Bibcode:2011Sci...334..252M. doi:10.1126/science.1208930. PMID 21868628. S2CID 20288929.

- Okolo S (2008). "Incidence, aetiology and epidemiology of uterine fibroids". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 22 (4): 571–588. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2008.04.002. PMID 18534913.

- Maruo T, Ohara N, Wang J, Matsuo H (2004). "Sex steroidal regulation of uterine leiomyoma growth and apoptosis". Human Reproduction Update. 10 (3): 207–220. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmh019. PMID 15140868.

- Yen-Ping Ho J, Man WC, Wen Y, Polan ML, Shih-Chu Ho E, Chen B (June 2009). "Transforming growth interacting factor expression in leiomyoma compared with myometrium". Fertil. Steril. 94 (3): 1078–83. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.05.001. PMC 2888713. PMID 19524896.

- Shozu M, Murakami K, Inoue M (2004). "Aromatase and Leiomyoma of the Uterus". Seminars in Reproductive Medicine. 22 (1): 51–60. doi:10.1055/s-2004-823027. PMID 15083381.

- Bulun SE, Yang S, Fang Z, Gurates B, Tamura M, Zhou J, Sebastian S (2001). "Role of aromatase in endometrial disease". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 79 (1–5): 19–25. doi:10.1016/S0960-0760(01)00134-0. PMID 11850203. S2CID 7642211.

- Moravek, MB; Yin, P; Ono, M; Coon, JS; Dyson, MT; Navarro, A; Marsh, EE; Chakravarti, D; Kim, JJ; Wei, JJ; Bulun, SE (February 2015). "Ovarian steroids, stem cells and uterine leiomyoma: therapeutic implications". Human Reproduction Update (Review). 21 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmu048. PMC 4255606. PMID 25205766.

- Hodge JC, Morton CC (2007). "Genetic heterogeneity among uterine leiomyomata: insights into malignant progression". Human Molecular Genetics. 16 Spec No 1: R7–13. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddm043. PMID 17613550.

- Awiwi, MO; Badawy, M; Shaaban, AM; Menias, CO; Horowitz, JM; Soliman, M; Jensen, CT; Gaballah, AH; Ibarra-Rovira, JJ; Feldman, MK; Wang, MX; Liu, PS; Elsayes, KM (13 May 2022). "Review of uterine fibroids: imaging of typical and atypical features, variants, and mimics with emphasis on workup and FIGO classification". Abdominal Radiology. 47 (7): 2468–2485. doi:10.1007/s00261-022-03545-x. PMID 35554629. S2CID 248725335.

- "Uterine fibroids - Diagnosis and treatment - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 2022-10-08.

- Mohamed Mokhtar Desouki. "Uterus - Stromal tumors - Leiomyoma". pathology Outlines. Topic Completed: 1 August 2011. Revised: 15 December 2019

- "Fibroids". NHS Choices. U.K. National Health Service. 2017-10-19. Archived from the original on 2008-05-05.

- Gupta JK, Sinha A, Lumsden MA, Hickey M (26 December 2014). "Uterine artery embolization for symptomatic uterine fibroids". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (12): CD005073. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005073.pub4. PMID 25541260.

- Zapata LB, Whiteman MK, Tepper NK, Jamieson DJ, Marchbanks PA, Curtis KM (2010). "Intrauterine device use among women with uterine fibroids: a systematic review☆". Contraception. 82 (1): 41–55. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2010.02.011. PMID 20682142.

- Sankaran S, Manyonda IT (2008). "Medical management of fibroids" (PDF). Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 22 (4): 655–76. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2008.03.001. PMID 18468953. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-09-11.

- Kailasam C, Cahill D (2008). "Review of the safety, efficacy and patient acceptability of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system". Patient Preference and Adherence. 2: 293–302. doi:10.2147/ppa.s3464. PMC 2770406. PMID 19920976.

- Talaulikar, VS; Manyonda, IT (August 2012). "Ulipristal acetate: a novel option for the medical management of symptomatic uterine fibroids". Advances in Therapy. 29 (8): 655–63. doi:10.1007/s12325-012-0042-8. PMID 22903240. S2CID 25905881.

- Pérez-López, FR (April 2015). "Ulipristal acetate in the management of symptomatic uterine fibroids: facts and pending issues". Climacteric. 18 (2): 177–81. doi:10.3109/13697137.2014.981133. PMID 25390187. S2CID 25077228.

- Donnez, Jacques; Tomaszewski, Janusz; Vázquez, Francisco; Bouchard, Philippe; Lemieszczuk, Boguslav; Baró, Francesco; Nouri, Kazem; Selvaggi, Luigi; Sodowski, Krzysztof; Bestel, Elke; Terrill, Paul (2012-02-02). "Ulipristal acetate versus leuprolide acetate for uterine fibroids". The New England Journal of Medicine. 366 (5): 421–432. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1103180. ISSN 1533-4406. PMID 22296076.

- Luyckx, Mathieu; Squifflet, Jean-Luc; Jadoul, Pascale; Votino, Rafaella; Dolmans, Marie-Madeleine; Donnez, Jacques (November 2014). "First series of 18 pregnancies after ulipristal acetate treatment for uterine fibroids". Fertility and Sterility. 102 (5): 1404–1409. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.07.1253. ISSN 1556-5653. PMID 25241376.

- Courtoy, Guillaume E.; Donnez, Jacques; Marbaix, Etienne; Dolmans, Marie-Madeleine (August 2015). "In vivo mechanisms of uterine myoma volume reduction with ulipristal acetate treatment". Fertility and Sterility. 104 (2): 426–434.e1. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.04.025. ISSN 1556-5653. PMID 26003270.

- Courtoy, Guillaume E.; Donnez, Jacques; Ambroise, Jérôme; Arriagada, Pablo; Luyckx, Mathieu; Marbaix, Etienne; Dolmans, Marie-Madeleine (August 2018). "Gene expression changes in uterine myomas in response to ulipristal acetate treatment". Reproductive Biomedicine Online. 37 (2): 224–233. doi:10.1016/j.rbmo.2018.04.050. ISSN 1472-6491. PMID 29807764. S2CID 44106868.

- Courtoy, Guillaume E.; Henriet, Patrick; Marbaix, Etienne; de Codt, Matthieu; Luyckx, Mathieu; Donnez, Jacques; Dolmans, Marie-Madeleine (1 April 2018). "Matrix Metalloproteinase Activity Correlates With Uterine Myoma Volume Reduction After Ulipristal Acetate Treatment". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 103 (4): 1566–1573. doi:10.1210/jc.2017-02295. ISSN 1945-7197. PMID 29408988.

- Donnez, Jacques; Donnez, Olivier; Matule, Dace; Ahrendt, Hans-Joachim; Hudecek, Robert; Zatik, Janos; Kasilovskiene, Zaneta; Dumitrascu, Mihai Cristian; Fernandez, Hervé; Barlow, David H.; Bouchard, Philippe (January 2016). "Long-term medical management of uterine fibroids with ulipristal acetate". Fertility and Sterility. 105 (1): 165–173.e4. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.09.032. ISSN 1556-5653. PMID 26477496.

- "European Medicament Agency".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Government of Canada, Health Canada (2020-09-16). "Allergan Inc. voluntarily withdraws its drug Fibristal, used to treat uterine fibroids, from the Canadian market". healthycanadians.gc.ca. Retrieved 2021-03-17.

- Tristan M, Orozco LJ, Steed A, Ramírez-Morera A, Stone P (2012). Orozco LJ (ed.). "Mifepristone for uterine fibroids". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8 (8): CD007687. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007687.pub2. PMC 8212859. PMID 22895965.

- Malartic C, Morel O, Akerman G, Tulpin L, Desfeux P, Barranger E (2008). "La mifépristone dans la prise en charge des fibromes utérins". Gynécologie Obstétrique & Fertilité. 36 (6): 668–74. doi:10.1016/j.gyobfe.2008.01.017. PMID 18539512.

- "The Embolisation Process". FEmISA: Fibroid Embolisation: Information, Support, Advice. Archived from the original on 2014-05-31.

- Gupta, JK; Sinha, A; Lumsden, MA; Hickey, M (26 December 2014). "Uterine artery embolization for symptomatic uterine fibroids". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (12): CD005073. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005073.pub4. PMID 25541260.

- Homer, Hayden; Saridogan, Ertan (June 2010). "Uterine artery embolization for fibroids is associated with an increased risk of miscarriage". Fertility and Sterility (Systematic review). 94 (1): 324–330. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.02.069. PMID 19361799.

- Liu WM, Ng HT, Wu YC, Yen YK, Yuan CC (2001). "Laparoscopic bipolar coagulation of uterine vessels: a new method for treating symptomatic fibroids". Fertility and Sterility. 75 (2): 417–22. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(00)01724-6. PMID 11172850.

- Akinola OI, Fabamwo AO, Ottun AT, Akinniyi OA (2005). "Uterine artery ligation for management of uterine fibroids". International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 91 (2): 137–40. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.07.012. PMID 16168993. S2CID 8042317.

- "Uterine Fibroid Embolisation Africa". 2017-02-23.

- Metwally, Mostafa; Raybould, Grace; Cheong, Ying C.; Horne, Andrew W. (29 January 2020). "Surgical treatment of fibroids for subfertility". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1: CD003857. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003857.pub4. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6989141. PMID 31995657.

- Agdi M, Tulandi T (August 2008). "Endoscopic management of uterine fibroids". Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 22 (4): 707–16. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2008.01.011. PMID 18325839.

- Bhave Chittawar P, Franik S, Pouwer AW, Farquhar C (Oct 21, 2014). "Minimally invasive surgical techniques versus open myomectomy for uterine fibroids". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10 (10): CD004638. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004638.pub3. PMID 25331441.

- Beck, Melinda (2010-01-20). "A New Treatment to Help Women Avoid Hysterectomy". The Wall Street Journal.

- "FDA Approves New Device to Treat Uterine Fibroids" (Press release). FDA. 2004-10-22. Archived from the original on 2008-05-09. Retrieved 2008-05-26.

- Shen SH, Fennessy F, McDannold N, Jolesz F, Tempany C (April 2009). "Image-guided thermal therapy of uterine fibroids". Seminars in Ultrasound, CT and MRI. 30 (2): 91–104. doi:10.1053/j.sult.2008.12.002. PMC 2768544. PMID 19358440.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Stewart EA, Rabinovici J, Tempany CM, Inbar Y, Regan L, Gostout B, Gastout B, Hesley G, Kim HS, Hengst S, Gedroyc WM, Gedroye WM (January 2006). "Clinical outcomes of focused ultrasound surgery for the treatment of uterine fibroids". Fertil. Steril. 85 (1): 22–9. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.04.072. PMID 16412721.

- Kurashvili J, Stepanov A, Kulabuchova E, Batarshina O (2014). "MRgFUS for Uterine Myomas: Safety, Effectiveness and Pathogenesis". Journal of Therapeutic Ultrasound. 2 (Suppl 1): A1–A25. doi:10.1186/2050-5736-2-S1-A1. PMC 4292016. PMID 25932673.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - "Helping Black Women Recognize, Treat Fibroids". NPR. Archived from the original on 22 January 2012. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- "African American Women and Fibroids". Philadelphia Black Women's Health Project. Archived from the original on 1 April 2011. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- "Minority Women's Health". Women's Health.gov. Archived from the original on 2010-08-30.

- "Black Women and High Prevalence of Fibroids". Fibroid Treatment Collective. November 29, 2010. Archived from the original on 25 December 2010. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- Office of Budget (PDF)Archived 2011-09-30 at the Wayback Machine

- Bäcklin BM, Eriksson L, Olovsson M (March 2003). "Histology of uterine leiomyoma and occurrence in relation to reproductive activity in the Baltic gray seal (Halichoerus grypus)". Vet. Pathol. 40 (2): 175–80. doi:10.1354/vp.40-2-175. PMID 12637757.