Vänern

Vänern (/ˈveɪnərn/ VAYN-ərn, also US: /ˈvɛn-/ VEN-,[3][4][5][6] Swedish: [ˈvɛ̂ːnɛɳ])[7] is the largest lake in Sweden, the largest lake in the European Union and the third-largest lake of all Europe after Ladoga and Onega in Russia. It is located in the provinces of Västergötland, Dalsland, and Värmland in the southwest of the country. With its surface located at 44 metres (144 ft) with a maximum depth of 106 metres (348 ft), the lowest point of the Vänern basin is at 62 metres (203 ft) below sea level. The average depth is at a more modest 28 metres (92 ft), which means that the average point of the lake floor remains above sea level.

| Vänern | |

|---|---|

View from Kinnekulle | |

Vänern | |

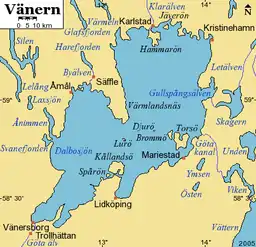

Detail map of the lake with surroundings | |

| Coordinates | 58°55′N 13°30′E |

| Primary inflows | Klarälven |

| Primary outflows | Göta älv |

| Basin countries | Sweden |

| Surface area | 5,650 km2 (2,180 sq mi)[1] |

| Average depth | 27 m (89 ft)[1] |

| Max. depth | 106 m (348 ft)[1] |

| Water volume | 153 km3 (37 cu mi)[1] |

| Residence time | 8 to 9 years[2] |

| Surface elevation | 44 m (144 ft)[1] |

| Islands | Brommö, Djurö, Fågelö, Hammarö, Kållandsö, Lurö (22,000 in total, including skerries[2]) |

| References | [1] |

Vänern drains into Göta älv towards Gothenburg and the Kattegat tributary of the Atlantic Ocean. It is the only one of the ten largest lakes in Sweden not to drain on the country's eastern coastline. Due to the construction of Göta Canal in the 19th century, there is an upstream water path to Vättern and the east coast from Vänern. The main inflow of water comes from Klarälven entering Vänern near Karlstad with its source in Trøndelag in Norway.

History

The southeastern part of the Vänern is a depression that appears to have come into being by erosion of Paleozoic-aged sedimentary rock during the Quaternary glaciation that reached to the area.[8] This erosion would have re-exposed parts of the Sub-Cambrian peneplain.[8] Because the southern and eastern shores are parts where the Sub-Cambrian peneplain gently tilts towards the north and west, respectively, the lake is rather shallow at these places.[8] The western shore of the lake largely follows a fault scarp associated to Vänern-Göta Fault.[8]

The modern lake was formed after the Quaternary glaciation about 10,000 years ago; when the ice melted, the entire width of Sweden was covered in water, creating a strait between Kattegat and the Gulf of Bothnia. Due to the fact that ensuing post-glacial rebound surpassed concurrent sea-level rise, lake Vänern became a part of the Ancylus Lake that occupied the Baltic basin.[9] Vänern was connected to Ancylus Lake by a strait at Degerfors, Värmland. Further uplifting made lakes such as Vänern and Vättern become cut off from the Baltic.[9] As a result, there are still species remaining from the ice age not normally encountered in freshwater lakes, such as the amphipod Monoporeia affinis. A Viking ship was found on the lake's bottom on May 6, 2009.[10]

A story told by the 13th-century Icelandic mythographer Snorri Sturluson in his Prose Edda about the origin of Mälaren was probably originally about Vänern: the Swedish king Gylfi promised a woman, Gefjon, as much land as four oxen could plough in a day and a night, but she used oxen from the land of the giants, and moreover uprooted the land and dragged it into the sea, where it became the island of Zealand. The Prose Edda says that 'the inlets in the lake correspond to the headlands in Zealand';[11] since this is much more true of Vänern, the myth was probably originally about Vänern, not Mälaren.[12]

The Battle on the Ice of Lake Vänern was a 6th-century battle recorded in the Norse sagas and referred to in the Old English epic Beowulf. In Beowulf, Vänern is stated to be near the location of the dragon's mound at Earnaness.[13]

Geography

Vänern covers an area of 5,655 km2 (2,183 sq mi). Its surface is 44 m (144 ft) above sea level and it is on average 27 m (89 ft) deep. The maximum depth of the lake is 106 m (348 ft).[14] The water level of the lake is regulated by the Vargön Hydroelectric Power Station.[15]

Geographically, it is situated on the border between the Swedish regions of Götaland and Svealand, divided between several Swedish provinces: The western body of water is known as the Dalbosjön, with its main part belonging to Dalsland; the eastern body is known as Värmlandsjön, its northern part belonging to Värmland and the southern to Västergötland.

Its main tributary is Klarälven, which flows into the lake near the city of Karlstad, on the northern shore. Other tributaries include Gullspångsälven, Byälven and Norsälven. It is drained to the south-west by Göta älv, which forms part of the Göta Canal waterway, to Lake Viken into Lake Vättern, southeast across Sweden.

The economic opportunities Vänern offers are illustrated by the surrounding towns, which have supported themselves for centuries by fishing and allowing easy transportation to other cities or west by Göta älv to the sea of Kattegat. This directly includes: Karlstad (chartered in 1584), Kristinehamn (1642), Mariestad (1583), Lidköping (1446) Vänersborg (1644), Åmål (1643), Säffle (1951), and indirectly Trollhättan (1916).

The Djurö archipelago surrounds the island of Djurö, in the middle of the lake, and has been given national park status as Djurö National Park.

The ridge (plateau mountain) Kinnekulle is a popular tourist attraction near the south-eastern shore of Vänern. It has the best view over the lake (about 270 metres (890 ft) above the lake level). Another nearby mountain is Halleberg.

Environment

Environmental monitoring studies are conducted annually. In a 2002 report, the data showed no marked decrease in overall water quality, but a slight decrease in visibility due to an increase of algae. An increasing level of nitrogen had been problematic during the 1970s through 1990s, but is now being regulated and is at a steady level.

Some bays also have problems with eutrophication and have become overgrown with algae and plant plankton.

Fish

Vänern has many different fish species. Locals and government officials try to enforce fishing preservation projects, due to threats to the fish habitat. These threats include water cultivation in the tributaries, pollution and the M74 syndrome. Sport fishing in Vänern is free and unregulated, both from the shore and from boats (with some restrictions, e.g. a maximum of three salmon or trout per person per day). Commercial fishing requires permission.

In the open waters of Vänern, the most common fish is the smelt (Osmerus eperlanus), dominating in the eastern Dalbosjön, where the average is 2,600 smelt per hectare. The second most common is the vendace (Coregonus albula), also most prominently in Dalbosjön, with 200–300 fish per hectare. The populations may vary greatly between years, depending on temperature, water level and quality.

Salmon

Lake Vänern has two remaining sub-groups of land-locked Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar), locally known as Vänern salmon ("Vänerlax"). They are both native to Lake Vänern and the parental fish all must spawn in the adjacent running waters to ensure survival and produce offspring. The first sub-group is named after an eastern tributary to the lake, Gullspångsälven, and is therefore called the Gullspång salmon ("Gullspångslax"). The second strain is the Klarälv salmon ("Klarälvslax"), mainly spawning in the Klarälven River drainage system, which is over 500 km long. The Klarälv salmon historically migrated as far as 400 km upstream into Norway to spawn in the northerly sections of the river.

These two sub-groups of salmonids are more related to the Baltic stocks than to North Sea stocks (Palm et al., 2012), and have both in their isolation distinctively developed in Lake Vänern for over 9,000 years (Willén, 2001). They are also very notable in that they have never entered the ocean and instead followed the deglaciation of Sweden's inland watersheds at the end of the Last Glacial Period. In the 1800s, annual catches in both Vänern and Klarälven were high (above 50.000 fish annually in Klarälven alone), but decreased during the 1900s to critically low levels in the 1960s, resembling many large rivers around the world (Parrish et al., 1998; Piccolo et al., 2012). Until the days of hydroelectric exploitation, the catches (with far less refined catching methods) of salmonids in Lake Vänern alone were around 100 tons annually. In addition there were catches in several other rivers and tributaries (Ros, 1981). The annual total catch of Vänern salmon therefore then likely exceeded 100.000 fish per year (350 to 400 metric tons).

These large, land-locked salmons are known to weigh up to 18 kg (40 lb) (Ros, 1981) in Lake Vänern. The Gullspång variant is now known as the larger and faster growing strain. Although that may have been different in the past, as from Klarälven there is historical information that a large and early-growing salmon stock, whose weight figure was between 8 kg and 17 kg, which it then reached while migrated up to its spawning grounds in the Norwegian tributary of Trysilälven. The world's largest registered landlocked salmon, exceeding 20 kg (44 lb), was also caught in nearby Lake Vättern in 1997, which was documented being of the Gullspång stock. A 23 kg (51 lb) specimen of the related species of brown trout ("Salmo trutta lacustris") has also been reported as being caught in the lake by local commercial fishermen (Ros, 1981). Gullspångsälven had, on the contrary, an early rise of smaller salmon (3–4 kg). This variant, called the “green ones” (“gröningen”), wandered through Lake Skagern up to the spawning grounds in Letälven. Of these 5 differentiated and separate strains of salmon in each of these rivers, both the spring-run fish in Gullspångsälven and the fall-run strain of Klarälven have both disappeared due to habit destruction (Ros, 1981). The early-running strain of large salmon that once spawned in the upper reaches in Norway is also extinct.

It is believed that at least 3 other subspecies of landlocked salmon have also previously gone extinct in the lake - mostly due to the construction of hydroelectric power plants and dams. This unique type of freshwater salmon hence also once inhabited Norsälven and its tributaries (the Frykfors power plant was built in 1905, but salmon fishing did not end in the river until 1944 after the obligation to keep the salmon ladders in place was removed and Edsvalla power plant began to be built), Byälven and its tributaries (which went extinct in the 1950s due to the construction of the power plant in Jössefors and no obligations to build fish ladders) and in Borgviksån (in 1939, a new power station was built by the upper falls of Borgviksån, without a fish ladder being built, blocking access to upstreams spawning grounds).

Large and unique populations of lake brown trout found in Lake Vänern, that also went extinct, include stocks from the drainage systems coming via Norsälven, Byälven, Upperudsälven, Åmålsån, Borgviksån, Lidan, and at the lakes outlet the rapids near Vargön (as a very special type of downstream spawning trout locally named “Vänerflabben”). Only Gullspångsälven and Tidan still have confirmed yet small self-sustaining migratory salmonid stocks left remaining coming from Vänern (Ros, 1981). The stocks in Klarälven are artificially maintained via human transport to spawning grounds above 9 power stations and the migratory brown trout population here is almost extinct. Nevertheless, most of these once unique subspecies of landlocked salmon once found in Lake Vänern have forever disappeared from the face of the earth due to man made incursions. There are also other species of salmonids (brown trout, Arctic char and grayling) found in the connecting lakes, rivers and streams. Some of these isolated lake brown trout strains are very large in size and genetically unique, although also today being severely threatened (Ros, 1981).

Negative environmental changes in the waters holding the juvenile stages of salmon (which have specific demands of clean and running water in their "pre-lake stage" that lasts 1–3 years) have had an undesired effect on the production of natural smolts now entering the lake. This is especially true in the Gullspång River - where it is believed that less than 1% of the natural smolt producing habitat remains in the surrounding watershed drainage system (Ros, 1981). Both salmon and trout also heavily rely upon being able to reach their spawning grounds, which is presently severely limited after the construction of numerous dams in both river systems. Other factors contributing to habitat deterioration include forestry & logging, agriculture, acidification of waters, pollution, road construction, fishing pressure, predators (mostly mink and cormorant - which are both accidentally introduced species) and climate change ([Nordberg 1977] and [Piccolo et al. 2012]).

The overall production of natural smolts is today thereby thought to be well under 10% of Lake Vänerns previous output and capacity ([P.O. Nordberg, unpublished data],[Christensen 2009], [Runnström 1940] and [Ros 1981]). Therefore, the salmon & trout populations in the lake today heavily rely upon fish farming of smolts - which are also released into the lake and some of its tributaries every year ([Swedish Board of Fisheries (Fiskeriverket)], [Fortum (the hydroelectric operating firm)], [the Värmland County Administrative Board (Länsstyrelssen I Värmland)] and [Statistics Sweden (SCB, http://www.scb.se)]). But this procedure has by no means proven to be adequate in replacing the previous natural production capacity held in these waters, leading to a demise in both volumes and the overall quality of the remaining wild strains.

The proportion of wild salmon and trout combined in the commercial catch in Vänern has increased from a maximum of 5% in 1997 (Fiskeriverket and Länsstyrelsen i Värmlands län, 1998) to up to 30–50% by 2008 (Degerman, 2008; Hållén, 2008; Johansson et al., 2009). The increasing proportion of wild fish in the lake could be a result of (1) increased natural production and/or protection of wild fish, and (2) declining numbers and/or decreased survival of hatchery smolt (Eriksson et al., 2008). Because the current fisheries in Lake Vänern are completely reliant on hatchery production, improving the survival rates of hatchery smolts could increase catch rates. Recently, however, declines in catch rates of hatchery-reared salmon and trout in Sweden nationwide have raised concerns about the condition, or ‘quality’, of the smolts being released (Eriksson et al. 2008; Swedish Board of Fisheries 2008). The power companies, bound by compensational duties due to verdicts in given licenses, have also been striving to release a higher percentage of 1 year old fish, as opposed to the more natural 2-year cycle. This entire prevailing situation has also led to a negative impact on both of the remaining populations genetic diversity (Ros, 1981) and their unique yet poorly preserved traits, leading to their present endangered status.

Other fish

The most important large fish in the lake are brown trout (Salmo trutta) and zander (Sander lucioperca). The most important small fish is the stickleback.

Vänern has five distinguished species of whitefish:

- Coregonus pallasii (also common in Neva, Gulf of Finland, Baltic Sea)

- Lacustrine fluvial whitefish (Coregonus megalops)

- Coregonus maxillaris (population mainly known around Sweden)[16]

- Coregonus nilssoni

- Valaam whitefish (Coregonus widegreni)

- Coregonus maxillaris

Birds

The most common birds near Vänern are terns and gulls.

Great cormorants have returned and are flourishing. This has contributed to the increase in the population of white-tailed sea eagles, who feed on cormorants.

See also

- Hindens Rev

- Lakes of Sweden

References

- Seppälä, Matti, ed. (2005), The Physical Geography of Fennoscandia, Oxford University Press, p. 145, ISBN 978-0-19-924590-1

- "Lake Vänern". www.vastsverige.com. West Sweden Tourism Board. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- "Vänern". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved April 14, 2019.

- "Vänern". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved April 14, 2019.

- "Vänern" (US) and "Vänern". Oxford Dictionaries UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press.

- "Vänern". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved April 14, 2019.

- Jöran Sahlgren; Gösta Bergman (1979). Svenska ortnamn med uttalsuppgifter (in Swedish). p. 28.

- Hall, Adrian M.; Krabbendam, Maarten; van Boeckel, Mikis; Hättestrand, Clas; Ebert, Karin; Heyman, Jakob (2019-12-01). The sub-Cambrian unconformity in Västergötland, Sweden: Reference surface for Pleistocene glacial erosion of basement (PDF) (Report). Swedish Nuclear Fuel and Wast Management Co. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

- Björck, Svante (1995). "A review of the history of the Baltic Sea, 13.0-8.0 ka BP". Quaternary International. 17: 19–40. Bibcode:1995QuInt..27...19B. doi:10.1016/1040-6182(94)00057-C.

- "'Viking ship' discovered in Sweden's largest lake". www.thelocal.se. 2009-05-08. Retrieved 2019-02-06.

- Anthony Faulkes (ed. and trans), Snorri Sturluson: Edda (London: Everyman, 1987), p. 7.

- Heimir Pálsson, 'Tertium vero datur: A study of the text of DG 11 4to', p. 44 http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-126249.

- Howell D. Chickering, Jr. (ed. and trans), Beowulf (New York: Anchor Books, 2006), lines 3030-3032.

- "World Lakes Database". Archived from the original on 2005-08-02. Retrieved 2006-04-22.

- "Våra kraftverk: Vargön - Vattenfall". powerplants.vattenfall.com (in Swedish).

- Fishbase