Visual impairment

Visual impairment, also known as vision impairment, is a medical definition primarily measured based on an individual's better eye visual acuity; in the absence of treatment such as correctable eyewear, assistive devices, and medical treatment– visual impairment may cause the individual difficulties with normal daily tasks including reading and walking.[6] Low vision is a functional definition of visual impairment that is chronic, uncorrectable with treatment or correctable lenses, and impacts daily living. As such low vision can be used as a disability metric and varies based on an individual's experience, environmental demands, accommodations, and access to services. The American Academy of Ophthalmology defines visual impairment as the best-corrected visual acuity of less than 20/40 in the better eye,[7] and the World Health Organization defines it as a presenting acuity of less than 6/12 in the better eye.[8] The term blindness is used for complete or nearly complete vision loss. In addition to the various permanent conditions, fleeting temporary vision impairment, amaurosis fugax, may occur, and may indicate serious medical problems.

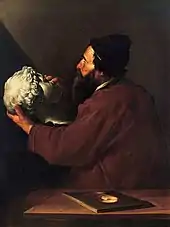

| Visual impairment | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Vision impairment, vision loss |

| |

| A white cane, the international symbol of blindness | |

| Specialty | Ophthalmology |

| Symptoms | Decreased ability to see[1][2] |

| Complications | Non-24-hour sleep–wake disorder, falls in older adults[3][4] |

| Causes | Uncorrected refractive errors, cataracts, glaucoma[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Eye examination[2] |

| Treatment | Vision rehabilitation, changes in the environment, assistive devices (eyeglasses, white cane)[2] |

| Frequency | 940 million / 13% (2015)[5] |

The most common causes of visual impairment globally are uncorrected refractive errors (43%), cataracts (33%), and glaucoma (2%).[1] Refractive errors include near-sightedness, far-sightedness, presbyopia, and astigmatism.[1] Cataracts are the most common cause of blindness.[1] Other disorders that may cause visual problems include age-related macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, corneal clouding, childhood blindness, and a number of infections.[9] Visual impairment can also be caused by problems in the brain due to stroke, premature birth, or trauma, among others.[10] These cases are known as cortical visual impairment.[10] Screening for vision problems in children may improve future vision and educational achievement.[11] Screening adults without symptoms is of uncertain benefit.[12] Diagnosis is by an eye exam.[2]

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 80% of visual impairment is either preventable or curable with treatment.[1] This includes cataracts, the infections river blindness and trachoma, glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, uncorrected refractive errors, and some cases of childhood blindness.[13] Many people with significant visual impairment benefit from vision rehabilitation, changes in their environment, and assistive devices.[2]

As of 2015 there were 940 million people with some degree of vision loss.[5] 246 million had low vision and 39 million were blind.[1] The majority of people with poor vision are in the developing world and are over the age of 50 years.[1] Rates of visual impairment have decreased since the 1990s.[1] Visual impairments have considerable economic costs both directly due to the cost of treatment and indirectly due to decreased ability to work.[14]

Classification

In 2010, the WHO definition for visual impairment was changed and now follows the ICD-11. The previous definition which used "best corrected visual acuity" was changed to "presenting visual acuity". This change was made as newer studies showed that best-corrected vision overlooks a larger proportion of the population who has visual impairment due to uncorrected refractive errors, and/or lack of access to medical or surgical treatment.[15]

Distance vision impairment:

- Category 0: No or mild visual impairment –presenting visual acuity better than 6/18

- Category 1: Moderate visual impairment –presenting visual acuity worse than 6/18 and better than 6/60

- Category 2: Severe visual impairment –presenting visual acuity worse than 6/60 and better than 3/60

- Category 3: Blindness –presenting visual acuity worse than 3/60 and better than 1/60

- Category 4: Blindness—presenting visual acuity worse than 1/60 with light perception

- Category 5: Blindness—irreversible blindness with no light perception

Near vision impairment:

- Near visual acuity worse than N6 or M.08 at 40 cm.

United Kingdom

Severely sight impaired

- Defined as having central visual acuity of less than 3/60 with normal fields of vision, or gross visual field restriction.

- Unable to see at 3 metres (10 ft) what the normally sighted person sees at 60 metres (200 ft).

Sight impaired

- Able to see at 3 metres (10 ft), but not at 6 metres (20 ft), what the normally sighted person sees at 60 metres (200 ft)

- Less severe visual impairment is not captured by registration data, and its prevalence is difficult to quantify

Low vision

- A visual acuity of less than 6/18 but greater than 3/60.

- Not eligible to drive and may have difficulty recognising faces across a street, watching television, or choosing clean, unstained, co-ordinated clothing.[16]

In the UK, the Certificate of Vision Impairment (CVI) is used to certify patients as severely sight impaired or sight impaired.[17] The accompanying guidance for clinical staff states: "The National Assistance Act 1948 states that a person can be certified as severely sight impaired if they are 'so blind as to be unable to perform any work for which eye sight is essential'". Certification is based on whether a person can do any work for which eyesight is essential, not just one particular job (such as their job before becoming blind).[18]

In practice, the definition depends on individuals' visual acuity and the extent to which their field of vision is restricted. The Department of Health identifies three groups of people who may be classified as severely visually impaired.[18]

- Those below 3/60 (equivalent to 20/400 in US notation) Snellen (most people below 3/60 are severely sight impaired).

- Those better than 3/60 but below 6/60 Snellen (people who have a very contracted field of vision only).

- Those 6/60 Snellen or above (people in this group who have a contracted field of vision especially if the contraction is in the lower part of the field).

The Department of Health also state that a person is more likely to be classified as severely visually impaired if their eyesight has failed recently or if they are an older individual, both groups being perceived as less able to adapt to their vision loss.[18]

United States

In the United States, any person with vision that cannot be corrected to better than 20/200 in the best eye, or who has 20 degrees (diameter) or less of visual field remaining, is considered legally blind or eligible for disability classification and possible inclusion in certain government sponsored programs.

In the United States, the terms partially sighted, low vision, legally blind and totally blind are used by schools, colleges, and other educational institutions to describe students with visual impairments.[19] They are defined as follows:

- Partially sighted indicates some type of visual problem, with a need of person to receive special education in some cases.

- Low vision generally refers to a severe visual impairment, not necessarily limited to distance vision. Low vision applies to all individuals with sight who are unable to read the newspaper at a normal viewing distance, even with the aid of eyeglasses or contact lenses. They use a combination of vision and other senses to learn, although they may require adaptations in lighting or the size of print, and, sometimes, braille.

- Legally blind indicates that a person has less than 20/200 vision in the better eye after best correction (contact lenses or glasses), or a field of vision of less than 20 degrees in the better eye.

- Totally blind students learn via braille or other non-visual media.

In 1934, the American Medical Association adopted the following definition of blindness:

Central visual acuity of 20/200 or less in the better eye with corrective glasses or central visual acuity of more than 20/200 if there is a visual field defect in which the peripheral field is contracted to such an extent that the widest diameter of the visual field subtends an angular distance no greater than 20 degrees in the better eye.[20]

The United States Congress included this definition as part of the Aid to the Blind program in the Social Security Act passed in 1935.[20][21] In 1972, the Aid to the Blind program and two others combined under Title XVI of the Social Security Act to form the Supplemental Security Income program[22] which states:

An individual shall be considered to be blind for purposes of this title if he has central visual acuity of 20/200 or less in the better eye with the use of a correcting lens. An eye which is accompanied by a limitation in the fields of vision such that the widest diameter of the visual field subtends an angle no greater than 20 degrees shall be considered for purposes of the first sentence of this subsection as having a central visual acuity of 20/200 or less. An individual shall also be considered to be blind for purposes of this title if he is blind as defined under a State plan approved under title X or XVI as in effect for October 1972 and received aid under such plan (on the basis of blindness) for December 1973, so long as he is continuously blind as so defined.[23]

Temporary vision impairment

Vision impairment for a few seconds, or minutes, may occur due to any of a variety of causes, some serious and requiring medical attention.

Health effects

General functioning

Visual impairments may take many forms and be of varying degrees. Visual acuity alone is not always a good predictor of an individual's function. Someone with relatively good acuity (e.g., 20/40) can have difficulty with daily functioning, while someone with worse acuity (e.g., 20/200) may function reasonably well if they have low visual demands. It is also important to note that best-corrected visual acuity differs from presenting visual acuity; a person with a "normal" best corrected acuity can have "poor" presenting acuity (e.g. individual who has uncorrected refractive error). Thus, measuring an individual's general functioning depends on one's situational and contextual factors, as well as access to treatment.[24]

The American Medical Association has estimated that the loss of one eye equals 25% impairment of the visual system and 24% impairment of the whole person;[25][26] total loss of vision in both eyes is considered to be 100% visual impairment and 85% impairment of the whole person.[25]

Some people who fall into this category can use their considerable residual vision – their remaining sight – to complete daily tasks without relying on alternative methods. The role of a low vision specialist (optometrist or ophthalmologist) is to maximize the functional level of a patient's vision by optical or non-optical means. Primarily, this is by use of magnification in the form of telescopic systems for distance vision and optical or electronic magnification for near tasks.

People with significantly reduced acuity may benefit from training conducted by individuals trained in the provision of technical aids. Low vision rehabilitation professionals, some of whom are connected to an agency for the blind, can provide advice on lighting and contrast to maximize remaining vision. These professionals also have access to non-visual aids, and can instruct patients in their uses.

Mobility

Older adults with visual impairment are at an increased risk of physical inactivity,[27][28] slower gait speeds,[29][30][31] and fear of falls.[32]

Physical activity is a useful predictor of overall well-being, and routine physical activity reduces the risk of developing chronic diseases and disability.[33][34] Older adults with visual impairment (including glaucoma, age-related macular degeneration, and diabetic retinopathy) have decreased physical activity as measured with self-reports and accelerometers.[35][36] The US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) showed that people with corrected visual acuity of less than 20/40 spent significantly less time in moderate to vigorous physical activity.[37] Age-related macular degeneration is also associated with a 50% decrease in physical activity–however physical activity is protective against age-related macular degeneration progression.[38][39]

In terms of mobility, those with visual impairment have a slower gait speed than those without visual impairment; however, the rate of decline remains proportional with increasing age in both groups. Additionally, the visually impaired also have greater difficulty walking a quarter mile (400 m) and walking up stairs, as compared to those with normal vision.[40]

Cognitive

Older adults with vision loss are at an increased risk of memory loss, cognitive impairment, and cognitive decline.[41]

Social and psychological

Studies demonstrate an association between older adults with visual impairment and a poor mental health;[42][43][44][45] discrimination was identified as one of the causes of this association.[46] Older adults with visual impairment have a 1.5-fold risk of reporting perceived discrimination and of these individuals, there was a 2-fold risk of loneliness and 4-fold risk of reporting a lower quality of life.[46] Among adults with visual impairment, the prevalence of moderate loneliness is 28.7% (18.2% in general population) and prevalence of severe loneliness is 19.7% (2.7% in general population).[42] The risk of depression and anxiety are also increased in the visually impaired; 32.2% report depressive symptoms (12.01% in general population), and 15.61% report anxiety symptoms (10.69% in general population).[44]

The subjects making the most use of rehabilitation instruments, who lived alone, and preserved their own mobility and occupation were the least depressed, with the lowest risk of suicide and the highest level of social integration.

Those with worsening sight and the prognosis of eventual blindness are at comparatively high risk of suicide and thus may be in need of supportive services. Many studies have demonstrated how rapid acceptance of the serious visual impairment has led to a better, more productive compliance with rehabilitation programs. Moreover, psychological distress has been reported to be at its highest when sight loss is not complete, but the prognosis is unfavorable. Therefore, early intervention is imperative for enabling successful psychological adjustment.[47]

Associated conditions

Blindness can occur in combination with such conditions as intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorders, cerebral palsy, hearing impairments, and epilepsy.[48][49] Blindness in combination with hearing loss is known as deafblindness.

It has been estimated that over half of completely blind people have non-24-hour sleep–wake disorder, a condition in which a person's circadian rhythm, normally slightly longer than 24 hours, is not entrained (synchronized) to the light–dark cycle.[50][51]

Cause

The most common causes of visual impairment globally in 2010 were:

- Refractive error (42%)

- Cataract (33%)

- Glaucoma (2%)

- Age-related macular degeneration (1%)

- Corneal opacification (1%)

- Diabetic retinopathy (1%)

- Childhood blindness

- Trachoma (1%)

- Undetermined (18%)[9]

The most common causes of blindness worldwide in 2010 were:

- Cataracts (51%)

- Glaucoma (8%)

- Age-related macular degeneration (5%)

- Corneal opacification (4%)

- Childhood blindness (4%)

- Refractive errors (3%)

- Trachoma (3%)

- Diabetic retinopathy (1%)

- Undetermined (21%)[9]

About 90% of people who are visually impaired live in the developing world.[1] Age-related macular degeneration, glaucoma, and diabetic retinopathy are the leading causes of blindness in the developed world.[52]

Among working-age adults who are newly blind in England and Wales the most common causes in 2010 were:[53]

- Hereditary retinal disorders (20.2%)

- Diabetic retinopathy (14.4%)

- Optic atrophy (14.1%)

- Glaucoma (5.9%)

- Congenital abnormalities (5.1%)

- Disorders of the visual cortex (4.1%)

- Cerebrovascular disease (3.2%)

- Degeneration of the macula and posterior pole (3.0%)

- Myopia (2.8%)

- Corneal disorders (2.6%)

- Malignant neoplasms of the brain and nervous system (1.5%)

- Retinal detachment (1.4%)

Cataracts

Cataracts are the greying or opacity of the crystalline lens, which can be caused in children by intrauterine infections, metabolic disorders, and genetically transmitted syndromes.[54] Cataracts are the leading cause of child and adult blindness that doubles in prevalence with every ten years after the age of 40.[55] Consequently, today cataracts are more common among adults than in children.[54] That is, people face higher chances of developing cataracts as they age. Nonetheless, cataracts tend to have a greater financial and emotional toll upon children as they must undergo expensive diagnosis, long term rehabilitation, and visual assistance.[56] Also, according to the Saudi Journal for Health Sciences, sometimes patients experience irreversible amblyopia[54] after pediatric cataract surgery because the cataracts prevented the normal maturation of vision prior to operation.[57] Despite the great progress in treatment, cataracts remain a global problem in both economically developed and developing countries.[58] At present, with the variant outcomes as well as the unequal access to cataract surgery, the best way to reduce the risk of developing cataracts is to avoid smoking and extensive exposure to sun light (i.e. UV-B rays).[55]

Glaucoma

Glaucoma is an eye disease often characterized by increased pressure within the eye or intraocular pressure (IOP).[59] Glaucoma causes visual field loss as well as severs the optic nerve.[60] Early diagnosis and treatment of glaucoma in patients is imperative because glaucoma is triggered by non-specific levels of IOP.[60] Also, another challenge in accurately diagnosing glaucoma is that the disease has four causes: 1) inflammatory ocular hypertension syndrome (IOHS); 2) severe uveitic angle closure; 3) corticosteroid-induced; and 4) a heterogonous mechanism associated with structural change and chronic inflammation.[59] In addition, often pediatric glaucoma differs greatly in cause and management from the glaucoma developed by adults.[61] Currently, the best sign of pediatric glaucoma is an IOP of 21 mm Hg or greater present within a child.[61] One of the most common causes of pediatric glaucoma is cataract removal surgery, which leads to an incidence rate of about 12.2% among infants and 58.7% among 10-year-olds.[61]

Infections

.jpg.webp)

Childhood blindness can be caused by conditions related to pregnancy, such as congenital rubella syndrome and retinopathy of prematurity. Leprosy and onchocerciasis each blind approximately 1 million individuals in the developing world.

The number of individuals blind from trachoma has decreased in the past 10 years from 6 million to 1.3 million, putting it in seventh place on the list of causes of blindness worldwide.

Central corneal ulceration is also a significant cause of monocular blindness worldwide, accounting for an estimated 850,000 cases of corneal blindness every year in the Indian subcontinent alone. As a result, corneal scarring from all causes is now the fourth greatest cause of global blindness.[62]

Injuries

Eye injuries, most often occurring in people under 30, are the leading cause of monocular blindness (vision loss in one eye) throughout the United States. Injuries and cataracts affect the eye itself, while abnormalities such as optic nerve hypoplasia affect the nerve bundle that sends signals from the eye to the back of the brain, which can lead to decreased visual acuity.

Cortical blindness results from injuries to the occipital lobe of the brain that prevent the brain from correctly receiving or interpreting signals from the optic nerve. Symptoms of cortical blindness vary greatly across individuals and may be more severe in periods of exhaustion or stress. It is common for people with cortical blindness to have poorer vision later in the day.

Blinding has been used as an act of vengeance and torture in some instances, to deprive a person of a major sense by which they can navigate or interact within the world, act fully independently, and be aware of events surrounding them. An example from the classical realm is Oedipus, who gouges out his own eyes after realizing that he fulfilled the awful prophecy spoken of him. Having crushed the Bulgarians, the Byzantine Emperor Basil II blinded as many as 15,000 prisoners taken in the battle, before releasing them.[63] Contemporary examples include the addition of methods such as acid throwing as a form of disfigurement.

Genetic defects

People with albinism often have vision loss to the extent that many are legally blind, though few of them actually cannot see. Leber congenital amaurosis can cause total blindness or severe sight loss from birth or early childhood. Retinitis pigmentosa is characterized by decreased peripheral vision and trouble seeing at night.

Advances in mapping of the human genome have identified other genetic causes of low vision or blindness. Two such examples are Bardet–Biedl syndrome .

Poisoning

Rarely, blindness is caused by the intake of certain chemicals. A well-known example is methanol, which is only mildly toxic and minimally intoxicating, and breaks down into the substances formaldehyde and formic acid which in turn can cause blindness, an array of other health complications, and death.[64] When competing with ethanol for metabolism, ethanol is metabolized first, and the onset of toxicity is delayed. Methanol is commonly found in methylated spirits, denatured ethyl alcohol, to avoid paying taxes on selling ethanol intended for human consumption. Methylated spirits are sometimes used by alcoholics as a desperate and cheap substitute for regular ethanol alcoholic beverages.

Other

- Amblyopia: is a category of vision loss or visual impairment that is caused by factors unrelated to refractive errors or coexisting ocular diseases.[57] Amblyopia is the condition when a child's visual systems fail to mature normally because the child either has been born premature, measles, congenital rubella syndrome, vitamin A deficiency, or meningitis.[65] If left untreated during childhood, amblyopia is currently incurable in adulthood because surgical treatment effectiveness changes as a child matures.[65] Consequently, amblyopia is the world's leading cause of child monocular vision loss, which is the damage or loss of vision in one eye.[57] In the best case scenario, which is very rare, properly treated amblyopia patients can regain 20/40 acuity.[57]

- Corneal opacification

- Degenerative myopia

- Diabetic retinopathy: is one of the manifestation microvascular complications of diabetes, which is characterized by blindness or reduced acuity. That is, diabetic retinopathy describes the retinal and vitreous hemorrhages or retinal capillary blockage caused by the increase of A1C,[66] which a measurement of blood glucose or sugar level.[67] In fact, as A1C increases, people tend to be at greater risk of developing diabetic retinopathy than developing other microvascular complications associated with diabetes (e.g. chronic hyperglycemia, diabetic neuropathy, and diabetic nephropathy).[66] Despite the fact that only 8% of adults 40 years and older experience vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy (e.g. nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy or NPDR and proliferative diabetic retinopathy or PDR), this eye disease accounted for 17% of cases of blindness in 2002.[66]

- Retinitis pigmentosa

- Retinopathy of prematurity: The most common cause of blindness in infants worldwide. In its most severe form, ROP causes retinal detachment, with attendant visual loss. Treatment is aimed mainly at prevention, via laser or Avastin therapy.

- Stargardt's disease

- Uveitis: is a group of 30 intraocular inflammatory diseases[68] caused by infections, systemic diseases, organ-specific autoimmune processes, cancer or trauma.[69] That is, uveitis refers to a complex category of ocular diseases that can cause blindness if either left untreated or improperly diagnosed.[69] The current challenge of accurately diagnosing uveitis is that often the cause of a specific ocular inflammation is either unknown or multi-layered.[68] Consequently, about 3–10% of those with uveitis in developed countries, and about 25% of those with uveitis in the developing countries, become blind from incorrect diagnosis and from ineffectual prescription of drugs, antibiotics or steroids.[69] In addition, uveitis is a diverse category of eye diseases that are subdivided as granulomatous (or tumorous) or non-granulomatous anterior, intermediate, posterior or pan uveitis.[69] In other words, uveitis diseases tend to be classified by their anatomic location in the eye (e.g. uveal tract, retina, or lens), as well as can create complication that can cause cataracts, glaucoma, retinal damage, age-related macular degeneration or diabetic retinopathy.[69]

- Xerophthalmia, often due to vitamin A deficiency, is estimated to affect 5 million children each year; 500,000 develop active corneal involvement, and half of these go blind.

Diagnosis

It is important that people be examined by someone specializing in low vision care prior to other rehabilitation training to rule out potential medical or surgical correction for the problem and to establish a careful baseline refraction and prescription of both normal and low vision glasses and optical aids. Only a doctor is qualified to evaluate visual functioning of a compromised visual system effectively.[70] The American Medical Association provides an approach to evaluating visual loss as it affects an individual's ability to perform activities of daily living.[25]

Screening adults who have no symptoms is of uncertain benefit.[12]

Prevention

The World Health Organization estimates that 80% of visual loss is either preventable or curable with treatment.[1] This includes cataracts, onchocerciasis, trachoma, glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, uncorrected refractive errors, and some cases of childhood blindness.[13] The Center for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that half of blindness in the United States is preventable.[2]

Management

Mobility

Many people with serious visual impairments can travel independently, using a wide range of tools and techniques. Orientation and mobility specialists are professionals who are specifically trained to teach people with visual impairments how to travel safely, confidently, and independently in the home and the community. These professionals can also help blind people to practice travelling on specific routes which they may use often, such as the route from one's house to a convenience store. Becoming familiar with an environment or route can make it much easier for a blind person to navigate successfully.

Tools such as the white cane with a red tip – the international symbol of blindness – may also be used to improve mobility. A long cane is used to extend the user's range of touch sensation. It is usually swung in a low sweeping motion, across the intended path of travel, to detect obstacles. However, techniques for cane travel can vary depending on the user and/or the situation. Some visually impaired persons do not carry these kinds of canes, opting instead for the shorter, lighter identification (ID) cane. Still others require a support cane. The choice depends on the individual's vision, motivation, and other factors.

A small number of people employ guide dogs to assist in mobility. These dogs are trained to navigate around various obstacles, and to indicate when it becomes necessary to go up or down a step. However, the helpfulness of guide dogs is limited by the inability of dogs to understand complex directions. The human half of the guide dog team does the directing, based upon skills acquired through previous mobility training. In this sense, the handler might be likened to an aircraft's navigator, who must know how to get from one place to another, and the dog to the pilot, who gets them there safely.

GPS devices can also be used as a mobility aid. Such software can assist blind people with orientation and navigation, but it is not a replacement for traditional mobility tools such as white canes and guide dogs.

Some blind people are skilled at echolocating silent objects simply by producing mouth clicks and listening to the returning echoes. It has been shown that blind echolocation experts use what is normally the "visual" part of their brain to process the echoes.[71][72]

Government actions are sometimes taken to make public places more accessible to blind people. Public transportation is freely available to blind people in many cities. Tactile paving and audible traffic signals can make it easier and safer for visually impaired pedestrians to cross streets. In addition to making rules about who can and cannot use a cane, some governments mandate the right-of-way be given to users of white canes or guide dogs.

Reading and magnification

Most visually impaired people who are not totally blind read print, either of a regular size or enlarged by magnification devices. Many also read large-print, which is easier for them to read without such devices. A variety of magnifying glasses, some handheld, and some on desktops, can make reading easier for them.

Others read braille (or the infrequently used Moon type), or rely on talking books and readers or reading machines, which convert printed text to speech or braille. They use computers with special hardware such as scanners and refreshable braille displays as well as software written specifically for the blind, such as optical character recognition applications and screen readers.

Some people access these materials through agencies for the blind, such as the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped in the United States, the National Library for the Blind or the RNIB in the United Kingdom.

Closed-circuit televisions, equipment that enlarges and contrasts textual items, are a more high-tech alternative to traditional magnification devices.

There are also over 100 radio reading services throughout the world that provide people with vision impairments with readings from periodicals over the radio. The International Association of Audio Information Services provides links to all of these organizations.

Computers and mobile technology

Access technology such as screen readers, screen magnifiers and refreshable braille displays enable the blind to use mainstream computer applications and mobile phones. The availability of assistive technology is increasing, accompanied by concerted efforts to ensure the accessibility of information technology to all potential users, including the blind. Later versions of Microsoft Windows include an Accessibility Wizard & Magnifier for those with partial vision, and Microsoft Narrator, a simple screen reader. Linux distributions (as live CDs) for the blind include Vinux and Adriane Knoppix, the latter developed in part by Adriane Knopper who has a visual impairment. macOS and iOS also come with a built-in screen reader called VoiceOver, while Google TalkBack is built in to most Android devices.

The movement towards greater web accessibility is opening a far wider number of websites to adaptive technology, making the web a more inviting place for visually impaired surfers.

Experimental approaches in sensory substitution are beginning to provide access to arbitrary live views from a camera.

Modified visual output that includes large print and/or clear simple graphics can be of benefit to users with some residual vision.[73]

Other aids and techniques

.jpg.webp)

Blind people may use talking equipment such as thermometers, watches, clocks, scales, calculators, and compasses. They may also enlarge or mark dials on devices such as ovens and thermostats to make them usable. Other techniques used by blind people to assist them in daily activities include:

- Adaptations of coins and banknotes so that the value can be determined by touch. For example:

- In some currencies, such as the euro, the pound sterling and the Indian rupee, the size of a note increases with its value.

- On US coins, pennies and dimes, and nickels and quarters are similar in size. The larger denominations (dimes and quarters) have ridges along the sides (historically used to prevent the "shaving" of precious metals from the coins), which can now be used for identification.

- Some currencies' banknotes have a tactile feature to indicate denomination. For example, the Canadian currency tactile feature is a system of raised dots in one corner, based on braille cells but not standard braille.[74]

- It is also possible to fold notes in different ways to assist recognition.

- Labeling and tagging clothing and other personal items

- Placing different types of food at different positions on a dinner plate

- Marking controls of household appliances

Most people, once they have been visually impaired for long enough, devise their own adaptive strategies in all areas of personal and professional management.

For the blind, there are books in braille, audio-books, and text-to-speech computer programs, machines and e-book readers. Low vision people can make use of these tools as well as large-print reading materials and e-book readers that provide large font sizes.

Computers are important tools of integration for the visually impaired person. They allow, using standard or specific programs, screen magnification and conversion of text into sound or touch (braille line), and are useful for all levels of visual impairment. OCR scanners can, in conjunction with text-to-speech software, read the contents of books and documents aloud via computer. Vendors also build closed-circuit televisions that electronically magnify paper, and even change its contrast and color, for visually impaired users. For more information, consult assistive technology.

In adults with low vision there is no conclusive evidence supporting one form of reading aid over another.[75] In several studies stand-mounted devices allowed faster reading than hand-held or portable optical aids.[75] While electronic aids may allow faster reading for individuals with low vision, portability, ease of use, and affordability must be considered for people.[75]

Children with low vision sometimes have reading delays, but do benefit from phonics-based beginning reading instruction methods. Engaging phonics instruction is multisensory, highly motivating, and hands-on. Typically students are first taught the most frequent sounds of the alphabet letters, especially the so-called short vowel sounds, then taught to blend sounds together with three-letter consonant-vowel-consonant words such as cat, red, sit, hot, sun. Hands-on (or kinesthetically appealing) VERY enlarged print materials such as those found in "The Big Collection of Phonics Flipbooks" by Lynn Gordon (Scholastic, 2010) are helpful for teaching word families and blending skills to beginning readers with low vision. Beginning reading instructional materials should focus primarily on the lower-case letters, not the capital letters (even though they are larger) because reading text requires familiarity (mostly) with lower-case letters. Phonics-based beginning reading should also be supplemented with phonemic awareness lessons, writing opportunities, and many read-alouds (literature read to children daily) to stimulate motivation, vocabulary development, concept development, and comprehension skill development. Many children with low vision can be successfully included in regular education environments. Parents may need to be vigilant to ensure that the school provides the teacher and students with appropriate low vision resources, for example technology in the classroom, classroom aide time, modified educational materials, and consultation assistance with low vision experts.

Epidemiology

The WHO estimates that in 2012 there were 285 million visually impaired people in the world, of which 246 million had low vision and 39 million were blind.[1]

Of those who are blind 90% live in the developing world.[76] Worldwide for each blind person, an average of 3.4 people have low vision, with country and regional variation ranging from 2.4 to 5.5.[77]

By age: Visual impairment is unequally distributed across age groups. More than 82% of all people who are blind are 50 years of age and older, although they represent only 19% of the world's population. Due to the expected number of years lived in blindness (blind years), childhood blindness remains a significant problem, with an estimated 1.4 million blind children below age 15.

By gender: Available studies consistently indicate that in every region of the world, and at all ages, females have a significantly higher risk of being visually impaired than males.[78][79][80][81][82][83]

By geography: Visual impairment is not distributed uniformly throughout the world. More than 90% of the world's visually impaired live in developing countries.[77]

Since the estimates of the 1990s, new data based on the 2002 global population show a reduction in the number of people who are blind or visually impaired, and those who are blind from the effects of infectious diseases, but an increase in the number of people who are blind from conditions related to longer life spans.[77]

In 1987, it was estimated that 598,000 people in the United States met the legal definition of blindness.[84] Of this number, 58% were over the age of 65.[84] In 1994–1995, 1.3 million Americans reported legal blindness.[85]

Society and culture

Legal definition

To determine which people qualify for special assistance because of their visual disabilities, various governments have specific definitions for legal blindness.[86] In North America and most of Europe, legal blindness is defined as visual acuity (vision) of 20/200 (6/60) or less in the better eye with best correction possible. This means that a legally blind individual would have to stand 20 feet (6.1 m) from an object to see it—with corrective lenses—with the same degree of clarity as a normally sighted person could from 200 feet (61 m). In many areas, people with average acuity who nonetheless have a visual field of less than 20 degrees (the norm being 180 degrees) are also classified as being legally blind. Approximately fifteen percent of those deemed legally blind, by any measure, have no light or form perception. The rest have some vision, from light perception alone to relatively good acuity. Low vision is sometimes used to describe visual acuities from 20/70 to 20/200.[87]

Antiquity

The Moche people of ancient Peru depicted the blind in their ceramics.[88]

In Greek myth, Tiresias was a prophet famous for his clairvoyance. According to one myth, he was blinded by the gods as punishment for revealing their secrets, while another holds that he was blinded as punishment after he saw Athena naked while she was bathing. In the Odyssey, the one-eyed Cyclops Polyphemus captures Odysseus, who blinds Polyphemus to escape. In Norse mythology, Loki tricks the blind god Höðr into killing his brother Baldr, the god of happiness.

The New Testament contains numerous instances of Jesus performing miracles to heal the blind. According to the Gospels, Jesus healed the two blind men of Galilee, the blind man of Bethsaida, the blind man of Jericho and the man who was born blind.

The parable of the blind men and an elephant has crossed between many religious traditions and is part of Jain, Buddhist, Sufi and Hindu lore. In various versions of the tale, a group of blind men (or men in the dark) touch an elephant to learn what it is like. Each one feels a different part, but only one part, such as the side or the tusk. They then compare notes and learn that they are in complete disagreement.

"Three Blind Mice" is a medieval English nursery rhyme about three blind mice whose tails are cut off after chasing the farmer's wife. The work is explicitly incongruous, ending with the comment Did you ever see such a sight in your life, As three blind mice?

Modern times

Poet John Milton, who went blind in mid-life, composed "On His Blindness", a sonnet about coping with blindness. The work posits that [those] who best Bear [God]'s mild yoke, they serve him best.

The Dutch painter and engraver Rembrandt often depicted scenes from the apocryphal Book of Tobit, which tells the story of a blind patriarch who is healed by his son, Tobias, with the help of the archangel Raphael.[89]

Slaver-turned-abolitionist John Newton composed the hymn "Amazing Grace" about a wretch who "once was lost, but now am found, Was blind, but now I see." Blindness, in this sense, is used both metaphorically (to refer to someone who was ignorant but later became knowledgeable) and literally, as a reference to those healed in the Bible. In the later years of his life, Newton himself would go blind.

H. G. Wells' story "The Country of the Blind" explores what would happen if a sighted man found himself trapped in a country of blind people to emphasise society's attitude to blind people by turning the situation on its head.

Bob Dylan's anti-war song "Blowin' in the Wind" twice alludes to metaphorical blindness: How many times can a man turn his head // and pretend that he just doesn't see... How many times must a man look up // Before he can see the sky?

Contemporary fiction contains numerous well-known blind characters. Some of these characters can see by means of devices, such as the Marvel Comics superhero Daredevil, who can see via his super-human hearing acuity, or Star Trek's Geordi La Forge, who can see with the aid of a VISOR, a fictional device that transmits optical signals to his brain.

Sports

Blind and partially sighted people participate in sports, such as swimming, snow skiing and athletics. Some sports have been invented or adapted for the blind, such as goalball, association football, cricket, golf, tennis, bowling, and beep baseball.[90][91] The worldwide authority on sports for the blind is the International Blind Sports Federation.[92][93] People with vision impairments have participated in the Paralympic Games since the 1976 Toronto summer Paralympics.[94]

Metaphorical uses

The word "blind" (adjective and verb) is often used to signify a lack of knowledge of something. For example, a blind date is a date in which the people involved have not previously met; a blind experiment is one in which information is kept from either the experimenter or the participant to mitigate the placebo effect or observer bias. The expression "blind leading the blind" refers to incapable people leading other incapable people. Being blind to something means not understanding or being aware of it. A "blind spot" is an area where someone cannot see: for example, where a car driver cannot see because parts of his car's bodywork are in the way; metaphorically, a topic on which an individual is unaware of their own biases, and therefore of the resulting distortions of their own judgements (see Bias blind spot).

Research

A 2008 study tested the effect of using gene therapy to help restore the sight of patients with a rare form of inherited blindness, known as Leber's congenital amaurosis or LCA.[95] Leber's Congenital Amaurosis damages the light receptors in the retina and usually begins affecting sight in early childhood, with worsening vision until complete blindness around the age of 30. The study used a common cold virus to deliver a normal version of the gene called RPE65 directly into the eyes of affected patients. All three patients, aged 19, 22 and 25, responded well to the treatment and reported improved vision following the procedure.

Two experimental treatments for retinal problems include a cybernetic replacement and transplant of fetal retinal cells.[96]

There is no high-quality evidence on the effect of assistive technologies on educational outcomes and quality of life in children with low vision as of 2015,[97] nor is there evidence on magnifying reading aids in children.[98] Low-vision rehabilitation does not appear to have an important impact on health-related quality of life, though some low-vision rehabilitation interventions, particularly psychological therapies and methods of enhancing vision, may improve vision-related quality of life in people with sight loss.[99]

Other animals

Statements that certain species of mammals are "born blind" refers to them being born with their eyes closed and their eyelids fused together; the eyes open later. One example is the rabbit. In humans, the eyelids are fused for a while before birth, but open again before the normal birth time; however, very premature babies are sometimes born with their eyes fused shut, and opening later. Other animals, such as the blind mole rat, are truly blind and rely on other senses.

The theme of blind animals has been a powerful one in literature. Peter Shaffer's Tony Award-winning play, Equus, tells the story of a boy who blinds six horses. Theodore Taylor's classic young adult novel, The Trouble With Tuck, is about a teenage girl, Helen, who trains her blind dog to follow and trust a seeing-eye dog.

See also

- Accessible Books Consortium

- Acute visual loss

- Blindness and education

- Color blindness

- Diplopia

- Nyctalopia

- Recovery from blindness

- Stereoblindness

- Tactile alphabet

- Tactile graphic

- Tangible symbol systems

- Visual agnosia

- Vision disorder

- Visual impairment due to intracranial pressure

- World Blind Union

References

- "Visual impairment and blindness Fact Sheet N°282". August 2014. Archived from the original on 12 May 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- "Blindness and Vision Impairment". February 8, 2011. Archived from the original on 29 April 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- Auger RR, Burgess HJ, Emens JS, Deriy LV, Thomas SM, Sharkey KM (October 2015). "Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Intrinsic Circadian Rhythm Sleep-Wake Disorders: Advanced Sleep-Wake Phase Disorder (ASWPD), Delayed Sleep-Wake Phase Disorder (DSWPD), Non-24-Hour Sleep-Wake Rhythm Disorder (N24SWD), and Irregular Sleep-Wake Rhythm Disorder (ISWRD). An Update for 2015: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline". Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 11 (10): 1199–236. doi:10.5664/jcsm.5100. PMC 4582061. PMID 26414986.

- Blaylock, SE; Vogtle, LK (June 2017). "Falls prevention interventions for older adults with low vision: A scoping review". Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 84 (3): 139–147. doi:10.1177/0008417417711460. PMID 28730900. S2CID 7567143.

- Vos T, Allen C, Arora M, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Brown A, et al. (GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators) (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- "Vision Impairment and Blindness | Examination-Based Studies | Information on Data Sources | Vision and Eye Health Surveillance System | Vision Health Initiative (VHI) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2021-08-10. Retrieved 2022-03-03.

- "Low Vision - American Academy of Ophthalmology". www.aao.org. Retrieved 2022-03-03.

- "Vision impairment and blindness". www.who.int. Retrieved 2022-03-03.

- GLOBAL DATA ON VISUAL IMPAIRMENTS 2010 (PDF). WHO. 2012. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-03-31.

- Lehman SS (September 2012). "Cortical visual impairment in children: identification, evaluation and diagnosis". Current Opinion in Ophthalmology. 23 (5): 384–7. doi:10.1097/ICU.0b013e3283566b4b. PMID 22805225. S2CID 33865357.

- Mathers M, Keyes M, Wright M (November 2010). "A review of the evidence on the effectiveness of children's vision screening". Child. 36 (6): 756–80. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01109.x. PMID 20645997.

- Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Baumann LC, Davidson KW, Ebell M, et al. (March 2016). "Screening for Impaired Visual Acuity in Older Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement". JAMA. 315 (9): 908–14. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.0763. PMID 26934260.

- "Causes of blindness and visual impairment". Archived from the original on 5 June 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- Rein DB (December 2013). "Vision problems are a leading source of modifiable health expenditures". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 54 (14): ORSF18-22. doi:10.1167/iovs.13-12818. PMID 24335062.

- "World report on vision". www.who.int. Retrieved 2022-03-03.

- Cupples, M., Hart, P., Johnston, A., & Jackson, A. (2011) Improving healthcare access for people with visual impairment and blindness BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.)

- "Identification and notification of sight loss". Archived from the original on 2011-05-03.

- "Certificate of Vision Impairment: Explanatory Notes for Consultant Ophthalmologists and Hospital Eye Clinic Staff" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-16.

- "National Dissemination Center for Children with Disabilities". Archived from the original on 2007-09-11.

- Koestler FA (1976). The unseen minority: a social history of blindness in the United States. New York: David McKay.

- Corn AL, Spungin SJ (April 2003). "Free and Appropriate Public Education and the Personnel Crisis for Students with Visual Impairments and Blindness" (PDF). Center on Personnel Studies in Special Education.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2015-05-23.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Social Security Act. "Sec. 1614. Meaning of terms". Archived from the original on 2015-05-23.

- "Vision impairment and blindness". www.who.int. Retrieved 2022-03-07.

- "AMA Guides" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-05-02.

- "Eye Trauma Epidemiology and Prevention". Archived from the original on 2006-05-28.

- Sengupta, Sabyasachi; Nguyen, Angeline M.; van Landingham, Suzanne W.; Solomon, Sharon D.; Do, Diana V.; Ferrucci, Luigi; Friedman, David S.; Ramulu, Pradeep Y. (2015-01-30). "Evaluation of real-world mobility in age-related macular degeneration". BMC Ophthalmology. 15: 9. doi:10.1186/1471-2415-15-9. ISSN 1471-2415. PMC 4328075. PMID 25636376.

- Willis, Jeffrey R.; Jefferys, Joan L.; Vitale, Susan; Ramulu, Pradeep Y. (March 2012). "Visual impairment, uncorrected refractive error, and accelerometer-defined physical activity in the United States". Archives of Ophthalmology. 130 (3): 329–335. doi:10.1001/archopthalmol.2011.1773. ISSN 1538-3601. PMID 22411662.

- CLARK-CARTER, D. D.; HEYES, A. D.; HOWARTH, C. I. (1986-06-01). "The efficiency and walking speed of visually impaired people". Ergonomics. 29 (6): 779–789. doi:10.1080/00140138608968314. ISSN 0014-0139. PMID 3743536.

- Patel, Ilesh; Turano, Kathleen A.; Broman, Aimee T.; Bandeen-Roche, Karen; Muñoz, Beatriz; West, Sheila K. (2006-01-01). "Measures of Visual Function and Percentage of Preferred Walking Speed in Older Adults: The Salisbury Eye Evaluation Project". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 47 (1): 65–71. doi:10.1167/iovs.05-0582. ISSN 1552-5783. PMID 16384945.

- Huang, Xiaoting; Chen, Zhixuan; Merchant, Reshma; Lim, Moses (2017-10-17). "Impact of vision impairment on gait speed relating to eventual risk of developing sarcopenia". International Journal of Integrated Care. 17 (5): A557. doi:10.5334/ijic.3877. ISSN 1568-4156.

- Ramulu, Pradeep Y.; van Landingham, Suzanne W.; Massof, Robert W.; Chan, Emilie S.; Ferrucci, Luigi; Friedman, David S. (July 2012). "Fear of falling and visual field loss from glaucoma". Ophthalmology. 119 (7): 1352–1358. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.01.037. ISSN 1549-4713. PMC 3389306. PMID 22480738.

- Warburton, D. E.; Gledhill, N.; Quinney, A. (April 2001). "Musculoskeletal fitness and health". Canadian Journal of Applied Physiology. 26 (2): 217–237. doi:10.1139/h01-013. ISSN 1066-7814. PMID 11312417.

- Warburton, D. E.; Glendhill, N.; Quinney, A. (April 2001). "The effects of changes in musculoskeletal fitness on health". Canadian Journal of Applied Physiology. 26 (2): 161–216. doi:10.1139/h01-012. ISSN 1066-7814. PMID 11312416.

- Heinemann, A. W.; Colorez, A.; Frank, S.; Taylor, D. (April 1988). "Leisure activity participation of elderly individuals with low vision". The Gerontologist. 28 (2): 181–184. doi:10.1093/geront/28.2.181. ISSN 0016-9013. PMID 3360359.

- Ong, Sharon R.; Crowston, Jonathan G.; Loprinzi, Paul D.; Ramulu, Pradeep Y. (August 2018). "Physical activity, visual impairment, and eye disease". Eye. 32 (8): 1296–1303. doi:10.1038/s41433-018-0081-8. ISSN 0950-222X. PMC 6085324. PMID 29610523.

- Willis, Jeffrey R.; Vitale, Susan E.; Agrawal, Yuri; Ramulu, Pradeep Y. (August 2013). "Visual impairment, uncorrected refractive error, and objectively measured balance in the United States". JAMA Ophthalmology. 131 (8): 1049–1056. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.316. ISSN 2168-6173. PMID 23744090.

- Seddon, Johanna M.; Cote, Jennifer; Davis, Nancy; Rosner, Bernard (June 2003). "Progression of age-related macular degeneration: association with body mass index, waist circumference, and waist-hip ratio". Archives of Ophthalmology. 121 (6): 785–792. doi:10.1001/archopht.121.6.785. ISSN 0003-9950. PMID 12796248.

- Knudtson, M. D.; Klein, R.; Klein, B. E. K. (December 2006). "Physical activity and the 15-year cumulative incidence of age-related macular degeneration: the Beaver Dam Eye Study". The British Journal of Ophthalmology. 90 (12): 1461–1463. doi:10.1136/bjo.2006.103796. ISSN 0007-1161. PMC 1857544. PMID 17077116.

- Swenor, B. K.; Munoz, B.; West, S. K. (2014-02-01). "A Longitudinal Study of the Association Between Visual Impairment and Mobility Performance in Older Adults: The Salisbury Eye Evaluation Study". American Journal of Epidemiology. 179 (3): 313–322. doi:10.1093/aje/kwt257. ISSN 0002-9262. PMC 3954103. PMID 24148711.

- Zheng, D. Diane; Swenor, Bonnielin K.; Christ, Sharon L.; West, Sheila K.; Lam, Byron L.; Lee, David J. (2018-09-01). "Longitudinal Associations Between Visual Impairment and Cognitive Functioning: The Salisbury Eye Evaluation Study". JAMA Ophthalmology. 136 (9): 989–995. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.2493. ISSN 2168-6165. PMC 6142982. PMID 29955805.

- Brunes, Audun; B. Hansen, Marianne; Heir, Trond (2019-02-01). "Loneliness among adults with visual impairment: prevalence, associated factors, and relationship to life satisfaction". Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 17 (1): 24. doi:10.1186/s12955-019-1096-y. ISSN 1477-7525. PMC 6359849. PMID 30709406.

- Demmin, Docia L; Silverstein, Steven M (2020-12-03). "Visual Impairment and Mental Health: Unmet Needs and Treatment Options". Clinical Ophthalmology. 14: 4229–4251. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S258783. ISSN 1177-5467. PMC 7721280. PMID 33299297.

- Aa, Hilde P. A. van der; Comijs, Hannie C.; Penninx, Brenda W. J. H.; Rens, Ger H. M. B. van; Nispen, Ruth M. A. van (2015-02-01). "Major Depressive and Anxiety Disorders in Visually Impaired Older Adults". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 56 (2): 849–854. doi:10.1167/iovs.14-15848. ISSN 1552-5783. PMID 25604690.

- CDC (2021-09-27). "Protect Your Vision". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2022-03-07.

- Jackson, Sarah E.; Hackett, Ruth A.; Pardhan, Shahina; Smith, Lee; Steptoe, Andrew (2019-07-01). "Association of Perceived Discrimination With Emotional Well-being in Older Adults With Visual Impairment". JAMA Ophthalmology. 137 (7): 825–832. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2019.1230. ISSN 2168-6165. PMC 6547384. PMID 31145413.

- De Leo D, Hickey PA, Meneghel G, Cantor CH (1999). "Blindness, fear of sight loss, and suicide". Psychosomatics. 40 (4): 339–44. doi:10.1016/S0033-3182(99)71229-6. PMID 10402881.

- "Causes of Blindness". Lighthouse International. Archived from the original on 12 June 2010. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- "Autism and Blindness". Nerbraska Center for the Education of Children who are Blind or Visually Impaired. Archived from the original on 8 August 2008. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- "Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorder" (PDF). American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-08-26. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- Sack RL, Lewy AJ, Blood ML, Keith LD, Nakagawa H (July 1992). "Circadian rhythm abnormalities in totally blind people: incidence and clinical significance". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 75 (1): 127–34. doi:10.1210/jcem.75.1.1619000. PMID 1619000.

- Bunce C, Wormald R (March 2006). "Leading causes of certification for blindness and partial sight in England & Wales". BMC Public Health. 6: 58. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-6-58. PMC 1420283. PMID 16524463.

- Liew G, Michaelides M, Bunce C (February 2014). "A comparison of the causes of blindness certifications in England and Wales in working age adults (16-64 years), 1999-2000 with 2009-2010". BMJ Open. 4 (2): e004015. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004015. PMC 3927710. PMID 24525390.

- Althomali T (2012). "Management of congenital cataract". Saudi Journal for Health Sciences. 1 (3): 115. doi:10.4103/2278-0521.106079.

- Brian G, Taylor H (2001). "Cataract blindness--challenges for the 21st century". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 79 (3): 249–56. PMC 2566371. PMID 11285671.

- Wirth MG, Russell-Eggitt IM, Craig JE, Elder JE, Mackey DA (July 2002). "Aetiology of congenital and paediatric cataract in an Australian population". The British Journal of Ophthalmology. 86 (7): 782–6. doi:10.1136/bjo.86.7.782. PMC 1771196. PMID 12084750.

- Rashad MA (2012). "Pharmacological enhancement of treatment for amblyopia". Clinical Ophthalmology. 6: 409–16. doi:10.2147/opth.s29941. PMC 3334227. PMID 22536029.

- Althomali T (2012). "Management of Congenital Cataract". Saudi Journal for Health Sciences. 1 (3): 115. doi:10.4103/2278-0521.106079.

- Krader CG (15 May 2012). "Etiology Determines IOP Treatment: Customized Approach Needed for Managing Elevated Pressure in Patients with Uveitis". Ophthalmology Times. Academic OneFile. 24.<"Gale - Institution Finder". Archived from the original on 2014-04-21. Retrieved 2014-05-05.>.

- Glaucoma Research Foundation. "High Eye Pressure and Glaucoma." Glaucoma Research Foundation. N.p., 5 Sept. 2013. Web.<"High Eye Pressure and Glaucoma". Archived from the original on 2017-09-02. Retrieved 2014-05-05.>.

- Meszaros L (15 September 2013). "Pediatric, Adult Glaucoma Differ in Management: Patient Populations Not Same, so Diagnosis/clinical Approach Should Reflect Their Uniqueness". Ophthalmology Times. Academic OneFile. 11. Archived from the original on 2014-04-21.

- (Vaughan & Asbury's General Ophthalmology, 17e)

- Finlay, George (1856). History of the Byzantine Empire from DCCXVI to MLVII, 2nd Edition, Published by W. Blackwood, pp. 444–445.

- "Methanol". Symptoms of Methanol Poisoning. Canada Safety Council. 2005. Archived from the original on 20 February 2007. Retrieved 27 March 2007.

- Gilbert C, Foster A (2001). "Childhood blindness in the context of VISION 2020--the right to sight". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 79 (3): 227–32. PMC 2566382. PMID 11285667.

- Morello CM (September 2007). "Etiology and natural history of diabetic retinopathy: an overview". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 64 (17 Suppl 12): S3–7. doi:10.2146/ajhp070330. PMID 17720892.

- "A1C and eAG". Archived from the original on 2014-06-03. Retrieved 2014-05-05.

- Jabs DA, Busingye J (August 2013). "Approach to the diagnosis of the uveitides". American Journal of Ophthalmology. 156 (2): 228–36. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2013.03.027. PMC 3720682. PMID 23668682.

- Rao NA (June 2013). "Uveitis in developing countries". Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 61 (6): 253–4. doi:10.4103/0301-4738.114090. PMC 3744776. PMID 23803475.

- "American Optometric Association web site". Archived from the original on 2013-06-05.

- Thaler L, Arnott SR, Goodale MA (2011). "Neural correlates of natural human echolocation in early and late blind echolocation experts". PLOS ONE. 6 (5): e20162. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...620162T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020162. PMC 3102086. PMID 21633496.

- Bat Man, Reader's Digest, June 2012, archived from the original on 15 March 2014, retrieved 14 March 2014

- Gregor, P., Newell, A.F., Zajicek, M. (2002). Designing for Dynamic Diversity – interfaces for older people. Proceedings of the fifth international ACM conference on Assistive technologies. Edinburgh, Scotland. Session: Solutions for aging. Pages 151–156.

- "Accessibility features – Bank Notes". Bank of Canada. Archived from the original on April 29, 2011.

- Virgili G, Acosta R, Bentley SA, Giacomelli G, Allcock C, Evans JR (April 2018). "Reading aids for adults with low vision". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (4): CD003303. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003303.pub4. PMC 6494537. PMID 29664159.

- Bosanquet N, Mehta P. "Evidence base to support the UK Vision Strategy". RNIB and The Guide Dogs for the Blind Association. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.649.6742.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - World Health Organization

- Esteban, J. J. Navarro; Martínez, M. Solera; Navalón, P. García; Serrano, O. Piñar; Patiño, J. R. Cerrillo; Purón, M. E. Calle; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V. (February 2008). "Visual impairment and quality of life: gender differences in the elderly in Cuenca, Spain". Quality of Life Research. 17 (1): 37–45. doi:10.1007/s11136-007-9280-7. ISSN 0962-9343. PMID 18026851. S2CID 24556942.

- Woldeyes, Alemayehu; Adamu, Yilkal (July 2008). "Gender differences in adult blindness and low vision, Central Ethiopia". Ethiopian Medical Journal. 46 (3): 211–218. ISSN 0014-1755. PMID 19271384.

- Rius Ulldemolins, Anna; Benach, Joan; Guisasola, Laura; Artazcoz, Lucía (2019-08-01). "Why are there gender inequalities in visual impairment?". European Journal of Public Health. 29 (4): 661–666. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cky245. hdl:2117/130141. ISSN 1464-360X. PMID 30500932.

- Mousa, Ahmed; Courtright, Paul; Kazanjian, Arminee; Bassett, Ken (2014-06-01). "Prevalence of Visual Impairment and Blindness in Upper Egypt: A Gender-based Perspective". Ophthalmic Epidemiology. 21 (3): 190–196. doi:10.3109/09286586.2014.906629. ISSN 0928-6586. PMID 24746251. S2CID 22521634.

- Ulldemolins, Anna Rius; Lansingh, Van C.; Valencia, Laura Guisasola; Carter, Marissa J.; Eckert, Kristen A. (September 2012). "Social inequalities in blindness and visual impairment: a review of social determinants". Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 60 (5): 368–375. doi:10.4103/0301-4738.100529. ISSN 1998-3689. PMC 3491260. PMID 22944744.

- Doyal, Lesley; Das-Bhaumik, Raja G. (2018). "Sex, gender and blindness: a new framework for equity". BMJ Open Ophthalmology. 3 (1): e000135. doi:10.1136/bmjophth-2017-000135. ISSN 2397-3269. PMC 6146307. PMID 30246151.

- Kirchner C, Stephen G, Chandu F (1987). "Estimated 1987 prevalence of non-institutionalized 'severe visual impairment' by age base on 1977 estimated rates: U. S.", 1987.". AER Yearbook.

- "Statistics and Sources for Professionals". American Foundation for the Blind. Archived from the original on 2008-08-07.

- "Defining the Boundaries of Low Vision Patients". SSDI Qualify. Archived from the original on January 27, 2014. Retrieved January 22, 2014.

- "Low Vision and Legal Blindness Terms and Descriptions". American Foundation for the Blind. Archived from the original on 2017-03-01. Retrieved 2017-02-28.

- Berrin, Katherine & Larco Museum. The Spirit of Ancient Peru:Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1997.

- Julius Held, Rembrandt and the Book of Tobit, Gehenna Press, Northampton MA, 1964.

- "Blind Sports Victoria". Archived from the original on 2008-02-21. Retrieved 2008-03-04.

- Chodosh S (24 March 2016). "The Competitive World of Blind Sports". The Atlantic. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- "IBSA General Assembly Elects New Leadership". The Paralympian. International Paralympic Committee. April 2001. Archived from the original on 2007-09-18. Retrieved 2008-03-04.

- Lin T (4 June 2012). "Hitting the Court, With an Ear on the Ball". Science. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 May 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- "The history of people with disabilities in Australia – 100 years". Disability Services Australia. Archived from the original on 2011-02-07. Retrieved 2008-03-04.

- Bainbridge JW, Smith AJ, Barker SS, Robbie S, Henderson R, Balaggan K, et al. (May 2008). "Effect of gene therapy on visual function in Leber's congenital amaurosis" (PDF). The New England Journal of Medicine. Massachusetts Medical Society. 358 (21): 2231–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0802268. hdl:10261/271174. PMID 18441371.

- Hamilton J (20 October 2009). "Bionic Eye Opens New World Of Sight For Blind". NPR. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- Thomas R, Barker L, Rubin G, Dahlmann-Noor A, et al. (Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group) (June 2015). "Assistive technology for children and young people with low vision". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6): CD011350. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011350.pub2. PMID 26086876.

- Barker L, Thomas R, Rubin G, Dahlmann-Noor A, et al. (Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group) (March 2015). "Optical reading aids for children and young people with low vision". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD010987. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010987.pub2. PMC 6769181. PMID 25738963.

- van Nispen RM, Virgili G, Hoeben M, Langelaan M, Klevering J, Keunen JE, van Rens GH, et al. (Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group) (January 2020). "Low vision rehabilitation for better quality of life in visually impaired adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1: CD006543. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006543.pub2. PMC 6984642. PMID 31985055.