Voyage of the James Caird

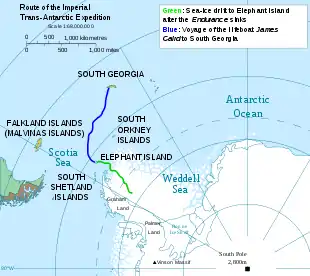

The voyage of the James Caird was a journey of 1,300 kilometres (800 mi) from Elephant Island in the South Shetland Islands through the Southern Ocean to South Georgia, undertaken by Sir Ernest Shackleton and five companions to obtain rescue for the main body of the stranded Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914–1917. Historians regard the voyage of the crew in a 22.5-foot (6.9 m) ship's boat through the "Furious Fifties" as one of the greatest small-boat journeys ever completed.

In October 1915, pack ice in the Weddell Sea had sunk the main expedition ship Endurance, leaving Shackleton and his 27 companions adrift on a floe. They drifted northward until April 1916, when the floe on which they were camped broke up; they made their way in the ship's boats to Elephant Island. Shackleton decided to sail one of the boats with a small crew to South Georgia to seek help. It was not the closest human settlement but the only one that did not require them to sail into the prevailing westerlies.

Of the three boats, the James Caird was deemed the most likely to survive the journey. (Shackleton had named it after Sir James Key Caird, a Dundee philanthropist whose sponsorship had helped finance the expedition.) Before its voyage, the ship's carpenter, Harry McNish, strengthened and adapted the boat to withstand the seas of the Southern Ocean, sealing his makeshift wood and canvas deck with lamp wick, oil paint and seal blood.

After surviving a series of dangers, including a near capsizing, the small crew and boat reached the southern coast of South Georgia after a 17-day voyage. Shackleton, Tom Crean and Frank Worsley crossed the island's mountains to a whaling station on the north side. Here they organised the relief of three men left on the south side of the island and of the larger Elephant Island party. Ultimately, the entire Endurance crew returned home, without loss of life. After the First World War, in 1919, the James Caird was moved from South Georgia to England. Since 1922 it has been on regular display at Shackleton's alma mater, school, Dulwich College.

Background

On 5 December 1914, Shackleton's expedition traveled via the ship Endurance from South Georgia for the Weddell Sea, on the first stage of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition.[1] They were making for Vahsel Bay, the southernmost explored point of the Weddell Sea at 77° 49' S, where a shore party was to land and prepare for a transcontinental crossing of Antarctica.[2] Before reaching its destination, the ship became trapped in pack ice, and by 14 February 1915 was held fast, despite prolonged efforts to free her.[3] During the following eight months the crew stayed with the ship as she drifted northward in the ice until, on 27 October, she was crushed by the pack's pressure, finally sinking on 21 November.[4]

As his 27-man crew set up camp on the slowly moving ice, Shackleton's focus shifted to how best to save his party.[5] His first plan was to march across the ice to the nearest land, and try to reach a point that ships were known to visit.[6] The march began, but progress was hampered by the nature of the ice's surface, later described by Shackleton as "soft, much broken up, open leads intersecting the floes at all angles".[7]

After struggling to make headway over several days, they abandoned the march; the party established "Patience Camp" on a flat ice floe, and waited as the drift carried them further north, towards open water.[8] They had managed to salvage the three boats, which Shackleton had named after the principal backers of the expedition: Stancomb-Wills, Dudley Docker and James Caird.[9] The party waited until 8 April 1916, when they finally took to the boats as the ice started to break up. Over a perilous period of seven days they sailed and rowed through stormy seas and dangerous loose ice, to reach the temporary haven of Elephant Island on 15 April.[10]

Elephant Island

Elephant Island, on the eastern limits of the South Shetland Islands, was remote from anywhere that the expedition had planned to go, and far beyond normal shipping routes. No relief ship would search for them there, and the likelihood of rescue from any other outside agency was equally negligible.[11] The island was bleak and inhospitable, and its terrain devoid of vegetation, although it had fresh water, and a relative abundance of seals and penguins to provide food and fuel for immediate survival.[12] The rigours of an Antarctic winter were fast approaching; the narrow shingle beach where they were camped was already being swept by almost continuous gales and blizzards, which destroyed one of the tents in their temporary camp, and knocked others flat. The pressures and hardships of the previous months were beginning to tell on the men, many of whom were in a run-down state both mentally and physically.[13]

In these conditions, Shackleton decided to try to reach help, using one of the boats. The nearest port was Stanley in the Falkland Islands, 570 nautical miles (1,100 km; 660 mi) away, but made unreachable by the prevailing westerly winds.[11] A better option was to head for Deception Island, 200 nautical miles (370 km; 230 mi) away at the western end of the South Shetland chain. Although it was uninhabited, Admiralty records indicated that this island held stores for shipwrecked mariners, and was also visited from time to time by whalers.[14] However, reaching it would also involve a journey against the prevailing winds—though in less open seas—with ultimately no certainty when or if rescue would arrive. After discussions with the expedition's second-in-command, Frank Wild, and ship's captain Frank Worsley, Shackleton decided to attempt to reach the whaling stations of South Georgia, to the north-east. This would mean a longer boat journey of 700 nautical miles (1,300 km; 810 mi) across the Southern Ocean, in conditions of rapidly approaching winter, but with the help of following winds it appeared feasible. Shackleton thought that "a boat party might make the voyage and be back with relief within a month, provided that the sea was clear of ice, and the boat survive the great seas".[11]

Preparations

The South Georgia boat party could expect to meet hurricane-force winds and waves—the notorious Cape Horn Rollers—measuring from trough to crest as much as 18 m (60 ft).[15] Shackleton therefore selected the heaviest and strongest of the three boats, the 22.5-foot (6.9 m) long James Caird.[16] It had been built as a whaleboat in London to Worsley's orders,[17] designed on the "double-ended" principle pioneered by Norwegian shipbuilder Colin Archer.[18] Knowing that a heavily-laden open sea voyage was now unavoidable, Shackleton had already asked the expedition's carpenter, Harry McNish to modify the boats during the weeks the expedition spent at Patience Camp. Using material taken from Endurance's fourth boat, a small motor launch which had been broken up with this purpose in mind before the ship's final loss, McNish had raised the sides of the James Caird and the Dudley Docker by 8–10 inches (20–25 cm). Now in the primitive camp on Elephant Island, McNish was again asked if he could make the James Caird more seaworthy.[19] Using improvised tools and materials, McNish built a makeshift deck of wood and canvas, sealing his work with oil paints, lamp wick, and seal blood.[20] The craft was strengthened by having the mast of the Dudley Docker lashed inside, along the length of her keel. She was then fitted as a ketch, with her own mainmast and a mizzenmast made by cutting down the mainmast from the Stancomb-Wills, rigged to carry lug sails and a jib.[21] The weight of the boat was increased by the addition of approximately 1 long ton (1 tonne) of ballast, to lessen the risk of capsizing in the high seas that Shackleton knew they would encounter.[21] Worsley believed that too much extra ballast (formed from rocks, stones and shingle taken from the beach) was added, making the boat excessively heavy, giving an extremely uncomfortable 'stiff' motion and hampering the performance for sailing upwind or into the weather. However he acknowledged that Shackleton's biggest concern was preventing the boat capsizing during the open-ocean crossing.[22]

The boat was loaded with provisions to last six men one month; as Shackleton later wrote, "if we did not make South Georgia in that time we were sure to go under".[19] They took ration packs that had been intended for the transcontinental crossing, biscuits, Bovril, sugar and dried milk. They also took two 18-gallon (68-litre) casks of water (one of which was damaged during the loading and let in sea water), two Primus stoves, paraffin, oil, candles, sleeping bags and odd items of spare clothing.[19]

Shackleton's first choices for the boat's crew were Worsley and Tom Crean, who had apparently "begged to go".[19] Crean was a shipmate from the Discovery Expedition, 1901–04, and had also been with Scott's Terra Nova Expedition in 1910–13, where he had distinguished himself on the fatal polar march.[23] Shackleton was confident that Crean would persevere to the bitter end,[21] and had great faith in Worsley's skills as a navigator, especially his ability to work out positions in difficult circumstances.[19] Worsley later wrote: "We knew it would be the hardest thing we had ever undertaken, for the Antarctic winter had set in, and we were about to cross one of the worst seas in the world".[24]

For the remaining places Shackleton requested volunteers, and of the many who came forward he chose two strong sailors in John Vincent and Timothy McCarthy. He offered the final place to the carpenter, McNish. "He was over fifty years of age", wrote Shackleton of McNish (he was in fact 41), "but he had a good knowledge of sailing boats and was very quick".[19] Vincent and McNish had each proved their worth during the difficult boat journey from the ice to Elephant Island.[21] They were both somewhat awkward characters, and their selection may have reflected Shackleton's wish to keep potential troublemakers under his personal charge rather than leaving them on the island where personal animosities could fester.[21]

Open-boat journey

Before leaving, Shackleton instructed Frank Wild that he was to assume full command as soon as the James Caird departed,[30] and that should the journey fail, he was to attempt to take the party to Deception Island the following spring.[19] The James Caird was launched from Elephant Island on 24 April 1916. The wind was a moderate south-westerly, which aided a swift getaway, and the boat was quickly out of sight of the land.[31]

Shackleton ordered Worsley to set a course due north, instead of directly for South Georgia, to get clear of the menacing ice-fields that were beginning to form.[32] By midnight they had left the immediate ice behind, but the sea swell was rising. At dawn the next day, they were 45 nautical miles (83 km; 52 mi) from Elephant Island, sailing in heavy seas and force 9 winds.[32] Shackleton established an on-board routine: two three-man watches, with one man at the helm, another at the sails, and the third on bailing duty.[32] The off-watch trio rested in the tiny covered space in the bows. The difficulties of exchanging places as each watch ended would, Shackleton wrote, "have had its humorous side if it had not involved us in so many aches and pains".[33] Their clothing was designed for Antarctic sledging rather than open-boat sailing. It was not waterproof, and contact with the icy seawater left their skins painfully raw.[34]

Success depended on Worsley's navigation, which was based on brief sightings of the sun as the boat pitched and rolled.[34] The first observation was made after two days, and showed them to be 128 nautical miles (237 km; 147 mi) north of Elephant Island.[32] The course was changed to head directly for South Georgia.[32] They were clear of floating ice but had reached the dangerous seas of the Drake Passage, where giant waves sweep round the globe, unimpeded by any land.[34] The movement of the ship made preparing hot food on the Primus nearly impossible, but Crean, who acted as cook, somehow kept the men fed.[32]

The next observation, on 29 April, showed that they had travelled 238 nautical miles (441 km; 274 mi).[35] Thereafter, navigation became, in Worsley's words, "a merry jest of guesswork",[36] as they encountered the worst of the weather. The James Caird was taking on water in heavy seas and in danger of sinking, kept afloat by continuous bailing. The temperature fell sharply, and a new danger presented itself in the accumulations of frozen spray, which threatened to capsize the boat.[37] In turns, they had to crawl out on to the pitching deck with an axe and chip away the ice from deck and rigging.[34] For 48 hours they were stopped, held by a sea anchor, until the wind dropped sufficiently for them to raise sail and proceed. Despite their travails, Worsley's third observation, on 4 May, put them only 250 nautical miles (460 km; 290 mi) from South Georgia.[38]

On 5 May the worst of the weather returned, and brought them close to disaster in the largest seas so far. Shackleton later wrote: "We felt our boat lifted and flung forward like a cork in breaking surf".[39] The crew bailed frantically to keep afloat. Nevertheless, they were still moving towards their goal, and a dead reckoning calculation by Worsley on the next day, 6 May, suggested that they were now 115 nautical miles (213 km; 132 mi) from the western point of South Georgia.[39] The strains of the past two weeks were by now taking their toll on the men. Shackleton observed that Vincent had collapsed and ceased to be an active member of the crew, McCarthy was "weak, but happy", McNish was weakening but still showing "grit and spirit".[39]

On 7 May Worsley advised Shackleton that he could not be sure of their position within ten miles.[40] To avoid the possibility of being swept past the island by the fierce south-westerly winds, Shackleton ordered a slight change of course so that the James Caird would reach land on the uninhabited south-west coast. They would then try to work the boat round to the whaling stations on the northern side of the island.[39] "Things were bad for us in those days", wrote Shackleton. "The bright moments were those when we each received our one mug of hot milk during the long, bitter watches of the night".[39] Late on the same day floating seaweed was spotted, and the next morning there were birds, including cormorants which were known never to venture far from land.[40] Shortly after noon on 8 May came the first sighting of South Georgia.[40]

As they approached the high cliffs of the coastline, heavy seas made immediate landing impossible. For more than 24 hours they were forced to stand clear, as the wind shifted to the north-west and quickly developed into "one of the worst hurricanes any of us had ever experienced".[39] For much of this time they were in danger of being driven on to the rocky South Georgia shore, or of being wrecked on the equally menacing Annenkov Island, five miles from the coast.[34] On 10 May, when the storm had eased slightly, Shackleton was concerned that the weaker members of his crew would not last another day, and decided that whatever the hazard they must attempt a landing. They headed for Cave Cove near the entrance to King Haakon Bay, and finally, after several attempts, made their landing there.[39] Shackleton was later to describe the boat journey as "one of supreme strife";[41] historian Caroline Alexander comments: "They could hardly have known—or cared—that in the carefully weighted judgement of authorities yet to come, the voyage of the James Caird would be ranked as one of the greatest boat journeys ever accomplished".[42]

South Georgia

As the party recuperated, Shackleton realised that the boat was not capable of making a further voyage to reach the whaling stations, and that Vincent and McNish were unfit to travel further. He decided to move the boat to a safer location within King Haakon Bay, from which point he, Worsley and Crean would cross the island on foot, aiming for the station at Stromness.[43]

On 15 May the James Caird made a run of about 6 nautical miles (11 km; 6.9 mi) to a shingle beach near the head of the bay. Here the boat was beached and up-turned to provide a shelter. The location was christened "Peggotty Camp" (after Peggotty's boat-home in Charles Dickens's David Copperfield).[44] Early on 18 May Shackleton, Worsley and Crean began what would be the first confirmed land crossing of the South Georgia interior.[45] Since they had no map, they had to improvise a route across mountain ranges and glaciers. They travelled continuously for 36 hours, before reaching Stromness. Shackleton's men were, in Worsley's words, "a terrible trio of scarecrows",[46] dark with exposure, wind, frostbite and accumulated blubber soot.[47] Later that evening, 19 May, a motor-vessel (the Norwegian whale catcher Samson)[48][49][50] was despatched to King Haakon Bay to pick up McCarthy, McNish and Vincent, and the James Caird.[51] Worsley wrote that the Norwegian seamen at Stromness all "claimed the honour of helping to haul her up to the wharf", a gesture which he found "quite affecting".[52]

The advent of the southern winter and adverse ice conditions meant that it was more than three months before Shackleton was able to achieve the relief of the men at Elephant Island. His first attempt was with the British ship Southern Sky. Then the government of Uruguay loaned him a ship. While searching on the Falkland Islands he found the ship Emma for his third attempt, but the ship's engine blew. Then, finally, with the aid of the steam-tug Yelcho commanded by Luis Pardo, the entire party was brought to safety, reaching Punta Arenas in Chile on 3 September 1916.[53]

Aftermath

The James Caird was returned to England in 1919.[54] In 1921, Shackleton went back to Antarctica, leading the Shackleton–Rowett Expedition. On 5 January 1922, he died suddenly of a heart attack, while the expedition's ship Quest was moored at South Georgia.[55]

Later that year John Quiller Rowett, who had financed this last expedition and was a former school friend of Shackleton's from Dulwich College, South London, decided to present the James Caird to the college. It remained there until 1967, although its display building was severely damaged by bombs in 1944.

In 1967, thanks to a pupil at Dulwich College, Howard Hope, who was dismayed at the state of the boat, it was given to the care of the National Maritime Museum, and underwent restoration. It was then displayed by the museum until 1985, when it was returned to Dulwich College and placed in a new location in the North Cloister, on a bed of stones gathered from South Georgia and Aberystwyth.[56] This site has become the James Caird's permanent home, although the boat is sometimes lent to major exhibitions and has taken part in the London Boat Show and in events at Greenwich, Portsmouth, and Falmouth. It has travelled overseas to be exhibited in Washington, D.C., New York, Sydney, Australia, Wellington (Te Papa) New Zealand and Bonn, Germany.[54]

The James Caird Society was established in 1994, to "preserve the memory, honour the remarkable feats of discovery in the Antarctic, and commend the outstanding qualities of leadership associated with the name of Sir Ernest Shackleton".[57]

In 2000, German polar explorer Arved Fuchs built a detailed copy of Shackleton's boat—named James Caird II—for his replication of the voyage of Shackleton and his crew from Elephant Island to South Georgia. The James Caird II was among the first exhibitions when the International Maritime Museum in Hamburg was opened. A further replica, James Caird III, was built and purchased by the South Georgia Heritage Trust, and since 2008 has been on display at the South Georgia Museum at Grytviken.[58]

Notes and references

Footnotes

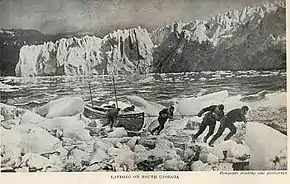

- Hurley captioned this photograph as the rescue party arriving at Elephant Island.[25] However, Worsley captioned it as the Caird leaving;[26] the State Library of New South Wales archived it under this same description[27] and has a similar image showing the masted Caird.[28] Author Caroline Alexander wrote that the original negative viewed at the Royal Geographical Society has a hole intentionally scratched in the center to erase the Caird and leave pictured the de-masted Stancomb-Wills, which helped launch the Caird; she included a print showing a hole right of the pictured boat.[29]

Citations

- Shackleton 1985, p. 3.

- Huntford 1985, p. 367.

- Shackleton 1985, pp. 29–34.

- Shackleton 1985, p. 98.

- Huntford 1985, p. 460.

- Huntford 1985, pp. 456–457.

- Shackleton 1985, pp. 102–106.

- Shackleton 1985, pp. 107–116.

- Huntford 1985, p. 469.

- Shackleton 1985, pp. 120–143, Shackleton (p. 143) claimed it as the first landing ever on the island..

- Shackleton 1985, pp. 156–157.

- Huntford 1985, p. 523.

- Alexander 1998, pp. 130–32.

- Shackleton 1985, p. 119.

- Alexander 1998, p. 132.

- Shackleton 1985, p. 149.

- Worsley 1999, p. 37.

- Huntford 1985, pp. 504, 525, The boat was sharp at stern and bow, to facilitate movement in either direction.

- Shackleton 1985, pp. 157–162.

- Huntford 1985, p. 525.

- Alexander 1998, pp. 134–135.

- Worsley 1999, p. 40.

- Huntford 1985, pp. 401–402.

- Worsley 1999, quoted in Barczewski 2007, p. 105.

- Hurley 1925, p. 278.

- Worsley 1939, p. 94.

- "Series 02: Slides of the British Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1914-1917, including expedition members, general views and the Endurance". digital.sl.nsw.gov.au. State Library of New South Wales. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- "Series 02: Slides of the British Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1914-1917, including expedition members, general views and the Endurance". digital.sl.nsw.gov.au. State Library of New South Wales.

- Alexander 1998, p. 202.

- Alexander 1998, p. 139.

- Huntford 1985, p. 527.

- Huntford 1985, pp. 548–553.

- Shackleton 1985, p. 167.

- Barczewski 2007, pp. 107–109.

- Huntford 1985, p. 555.

- Worsley 1999, p. 88.

- Huntford 1985, p. 557.

- Huntford 1985, p. 560.

- Shackleton 1985, pp. 174–179.

- Alexander 1998, p. 150.

- Shackleton 1985, p. 165.

- Alexander 1998, p. 153.

- Shackleton 1985, pp. 185–186 and p. 191.

- Shackleton 1985, p. 191.

- Huntford 1985, p. 571, states that Norwegian skiers had "probably" crossed at various points, but these journeys were not recorded.

- Quoted by Huntford 1985, p. 597.

- Huntford 1985, pp. 597–598.

- "Exploring the explorer – Traces of Ernest Shackleton". libraryblogs.is.ed.ac.uk/edinburghuniversityarchives. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- "The voyage of the 'James Caird'". shackletonlegacy.com. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- "Tom Crean, an Irish Antarctic explorer". tomcreandiscovery.com. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- Shackleton 1985, p. 208.

- Worsley 1999, quoted in Huntford 1985, p. 602.

- Shackleton 1985, pp. 210–222.

- "The James Caird Society". James Caird Society. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- Huntford 1985, pp. 689–690.

- "Eminent Old Alleynians: Sir Ernest Shackleton". Dulwich College. Archived from the original on 22 June 2013. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- "The James Caird". Dulwich College. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- Davidson, Elsa (April 2009). "The Carr Maritime Gallery, South Georgia Museum" (PDF). South Georgia Association Newsletter. Huntingdon. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

Bibliography

- Alexander, C. (1998). The Endurance: Shackleton's legendary Antarctic expedition. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 9780747541233.

- Barczewski, S. (2007). Antarctic Destinies. London: Hambledon Continuum. ISBN 9781847251923.

- Huntford, R. (1985). Shackleton. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 9780340250075.

- Hurley, F. (1925). Argonauts of the South. London: Butler & Tanner.

- Shackleton, E. (1985). South: The story of Shackleton's 1914–17 expedition. London: Century Publishing. ISBN 9780712601115.

- Worsley, F. A. (1939) [1931]. Endurance: An Epic of Polar Adventure. London: Butler & Tanner.

- Worsley, F. A. (1999). Shackleton's Boat Journey. London: W. W. Norton. ISBN 9780712665742.