William T. Stearn

William Thomas Stearn /stɜːrn/ CBE FLS VMH (16 April 1911 – 9 May 2001) was a British botanist. Born in Cambridge in 1911, he was largely self-educated, and developed an early interest in books and natural history. His initial work experience was at a Cambridge bookshop, but he also had a position as an assistant in the university botany department. At the age of 29 he married Eldwyth Ruth Alford, who later became his collaborator, and he died in London in 2001.

William Thomas Stearn CBE FLS VMH | |

|---|---|

W. T. Stearn, 1974 | |

| Born | 16 April 1911 Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, England |

| Died | 9 May 2001 (aged 90) Kingston upon Thames, London, England |

| Education | Cambridge High School for Boys |

| Known for | Botanical taxonomy, history of botany, Botanical Latin, horticulture |

| Spouse | Eldwyth Ruth Alford (m. 1940) |

| Children | 3 |

| Awards | Veitch Memorial Medal (1964), Victoria Medal of Honour (1965), Linnean Medal (1976), Commander of the Swedish Order of the Star of the North (1980), Engler Gold Medal (1993), Commander of the Order of the British Empire (1997), Asa Gray Award (2000) |

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions | Botany School, Cambridge, Lindley Library, Natural History Museum |

| Influences | Albert Seward, Agnes Arber, John Gilmour, Humphrey Gilbert-Carter, Harry Godwin, E. A. Bowles |

| Influenced | Ghillean Prance, Peter H. Raven, Norman Robson, Max Walters, Vernon Heywood, John Akeroyd |

| Author abbrev. (botany) | Stearn |

While at the bookshop, he was offered a position as a librarian at the Royal Horticultural Society in London (1933–1952). From there he moved to the Natural History Museum as a scientific officer in the botany department (1952–1976). After his retirement, he continued working there, writing, and serving on a number of professional bodies related to his work, including the Linnean Society, of which he became president. He also taught botany at Cambridge University as a visiting professor (1977–1983).

Stearn is known for his work in botanical taxonomy and botanical history, particularly classical botanical literature, botanical illustration and for his studies of the Swedish scientist Carl Linnaeus. His best known books are his Dictionary of Plant Names for Gardeners, a popular guide to the scientific names of plants, and his Botanical Latin for scientists.

Stearn received many honours for his work, at home and abroad, and was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in 1997. Considered one of the most eminent British botanists of his time, he is remembered by an essay prize in his name from the Society for the History of Natural History, and a named cultivar of Epimedium, one of many genera he produced monographs on. He is the botanical authority for over 400 plants that he named and described.

Life

Childhood

William Thomas Stearn was born at 37 Springfield Road, Chesterton, Cambridge, England, on 16 April 1911, the eldest of four sons, to Thomas Stearn (1871 or 1872–1922) and Ellen ("Nellie") Kiddy (1886–1986) of West Suffolk.[1] His father worked as a coachman to a Cambridge doctor. Chesterton was then a village on the north bank of the River Cam, about two miles north of Cambridge's city centre, where Springfield Road ran parallel to Milton Road to the west.[2] William Stearn's early education was at the nearby Milton Road Junior Council School (see image).[lower-alpha 1] Despite not having any family background in science (though he recalled that his grandfather was the university rat-catcher)[5] he developed a keen interest in natural history and books at an early age. He spent his school holidays on his uncle's Suffolk farm, tending cows grazing by the roadside where he would observe the wild flowers of the hedgerows and fields.[6] Stearn's father died suddenly in 1922 when Stearn was only eleven, leaving his working-class family in financial difficulties as his widow (Stearn's mother) had no pension.[7]

That year, William Stearn succeeded in obtaining a scholarship to the local Cambridge High School for Boys on Hills Road, close to the Cambridge Botanic Garden, which he attended for eight years till he was 18.[1] The school had an excellent reputation for biology education,[8] and while he was there, he was encouraged by Mr Eastwood, a biology teacher who recognised his talents.[9] The school also provided him with a thorough education in both Latin and Greek.[9] He became secretary of the school's Natural History Society, won an essay prize from the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds and spent much of his time at the Botanic Garden.[lower-alpha 2] Stearn also gained horticultural experience by working as a gardener's boy during his school holidays, to supplement the family income.[2][11]

Stearn attended evening lectures on paleobotany given by Albert Seward (chair of botany at Cambridge University 1906–1936), and Harry Godwin.[12] Seward was impressed by the young Stearn, giving him access to the herbarium of the Botany School (now Department of Plant Sciences—see 1904 photograph) and allowing him to work there as a part-time research assistant.[2] Later, Seward also gave Stearn access to the Cambridge University Library to pursue his research.[1][8]

Later life

Stearn was largely self-educated and his widowed mother worked hard to support him while at school but could not afford a university education for him, there being no grants available then.[13] When not at the Botany School, he attended evening classes to develop linguistic and bibliographic skills. His classes there included German and the classics.[7] He obtained his first employment at the age of 18 in 1929, a time of high unemployment, to support himself and his family. He worked as an apprentice antiquarian bookseller and cataloguer in the second-hand section at Bowes & Bowes bookshop,[lower-alpha 3] 1 Trinity Street (now Cambridge University Press), between 1929 and 1933 where he was able to pursue his passion for bibliography.[15] During his employment there, he spent much of his lunchtimes, evenings and weekends, at the Botany School and Botanic Garden.[8][11] This was at a time when botany was thriving at Cambridge under the leadership of Seward and Humphrey Gilbert-Carter.[13]

On 3 August 1940, he married Eldwyth Ruth Alford (1910–2013), by whom he had a son and two daughters, and who collaborated with him in much of his work.[13][16] Ruth Alford was a secondary school teacher from Tavistock, Devon, the daughter of Roger Rice Alford a Methodist preacher and mayor of Tavistock. When their engagement was announced in The Times, Stearn was vastly amused to see that he was described as a "Fellow of the Linen Society", a typographical error for Linnean Society.[5] Stearn was brought up an Anglican, but was a conscientious objector and after the Second World War he became a Quaker.[15] In his later years, following official retirement in 1976 he continued to live in Kew, Richmond.[2] His entry in Who's Who lists his interests as "gardening and talking".[17] He died on 9 May 2001 of pneumonia at Kingston Hospital, Kingston upon Thames, at the age of 90.[7][15][18] His funeral took place on 18 May at Mortlake crematorium. He left three children (Roger Thomas Stearn, Margaret Ruth Stearn and Helen Elizabeth Stearn) and an estate of £461,240.[1] His wife, whose 100th birthday was celebrated at the Linnean Society in 2010, lived to the age of 103.[19]

Professor Stearn had a reputation for his encyclopedic knowledge, geniality, wit and generosity with his time and knowledge, being always willing to contribute to the work of others.[20] He had a mischievous sense of fun and was famous for his anecdotes while lecturing,[21] while his colleagues recalled that "he had a happy genius for friendship".[22] He was described as having a striking figure, "a small man, his pink face topped with a thatch of white hair",[9] and earned the nickname of "Wumpty" after his signature of "Wm. T. Stearn".[23][24]

Career

.jpg.webp)

Cambridge years (1929–1933)

Stearn began his career as a gardener at Sidney Sussex College after leaving school at 13. He then became a bookseller at Bowes & Bowes. While working at the bookshop he made many friends among the Cambridge botanists and participated in their activities, including botanical excursions. In addition to Professor Seward, those influencing him included the morphologist Agnes Arber, Humphrey Gilbert-Carter the first scientific director of the Botanic Garden, John Gilmour then curator of the university herbarium and later director of the Garden (1951–1973), the horticulturalist E. A. Bowles (1865–1954), who became his patron,[15] Harry Godwin, then a research fellow and later professor and Tom Tutin who was working with Seward at that time.[2] Seward gave him full research facilities in the herbarium. He continued his research, visiting the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew, in 1930, at the age of 19, and also spent two weeks at the herbarium of the Musée National d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris, with the aid of a £15 grant from the Royal Society to study Epimedium.[25] Also in 1930, the Fifth International Botanical Congress was held at Cambridge, and Stearn was able to attend.[12] During this time he commuted between the bookshop, the Botany School, Botanic Garden and home by bicycle, his preferred means of transportation throughout his life.[8]

Lindley Library, Royal Horticultural Society (1933–1952)

In 1933, H. R. Hutchinson, who was the Librarian at the Lindley Library, Royal Horticultural Society's (RHS) in London, was due to retire. John Gilmour, now assistant director at the Kew Gardens, put forward Stearn's name, together with Bowles, a vice-president of the Society, who had discovered Stearn at the bookshop. Stearn was 22 when he began work at the library, initially as assistant librarian, before taking over Hutchinson's position after six months. He later explained his appointment at such a young age as being the result of World War I: "All the people who should have had those jobs were dead."[5] There he collaborated with Bowles on a number of plant monographs, such as Bowles' Handbook of Crocus[26] and their work on Anemone japonica (Anemone hupehensis var. japonica).[27][lower-alpha 4] Written in 1947, it is still considered one of the most comprehensive accounts of the origins and nomenclature of fall-blooming anemones.[29] Stearn was one of the last people to see Bowles alive,[30] and when Bowles died, Stearn wrote an appreciation of him,[31] and later contributed the entry on Bowles to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.[32] Much of his spare time was spent studying at the Kew Gardens.[11]

The Lindley Library, the largest horticultural library in the world and named after the British botanist John Lindley (1799–1865), was established in 1868 by the acquisition of Lindley's 1,300 volumes upon his death.[2][33] It had recently undergone considerable change. In 1930, the library had been rehoused in a new floor added to the society's Vincent Square headquarters, but the role of the library was somewhat downgraded. Frederick Chittenden had been appointed as Keeper of the Library (1930–1939), and Hutchinson reported directly to him. Stearn related that when he reported for duty, Hutchinson was completely unaware of the appointment of his new assistant.[12]

Lindley was one of Stearn's inspirations, also being a librarian who had a long association with the RHS. Lindley also bequeathed his herbarium to the Cambridge University Herbarium, where it now forms the Lindley Collection.[34] As Stearn remarked "I came to know his numerous publications and to admire the industry, tenacity and ability with which he undertook successfully so many different things".[35] Later Stearn would publish a major work on Lindley's life and work.[36] Lindley's contributions to horticultural taxonomy were matched only by those of Stearn himself.[5] Stearn soon set about using his antiquarian knowledge to reorganise the library, forming a pre-Linnean section.[9] Not long after his arrival the library acquired one of its largest collections, the Reginald Cory Bequest (1934),[37][38] which Stearn set about cataloguing on its arrival two years later, resulting in at least fifteen publications.[39]

While at the library he continued his self-education through evening classes, learning Swedish, and travelling widely. Stearn used his three-week annual leaves in the pre-war years to visit other European botanical libraries, botanic gardens, museums, herbaria and collections, as well as collecting plants, with special emphasis on Epimedium and Allium.[2] His travels took him to Switzerland, Italy, Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, and Sweden.[39]

War years (1941–1946)

The only break from this employment was the war years 1941–1946, leaving his assistant Ms. Cardew as acting librarian.[12] Initially Stearn served as an air raid warden, before enlisting. As a conscientious objector, he could not serve in a combatant role, but was accepted into the Royal Air Force (RAF) Medical Services, as he had previously worked with the St John Ambulance Brigade. He served in the RAF in both England, and Asia (India and Burma, where he worked in intelligence, and was awarded the Burma Star). While there he undertook studies of Indo-Malayan and Sikkim-Himalayan tropical vegetation,[8] carried out botanical explorations, taught biology to troops and began work on his Botanical Latin.[lower-alpha 5] His wartime observations led to collaborative publications such as An enumeration of the flowering plants of Nepal (1978–1982),[41] Beautiful Indian Trees (2nd ed. 1954),[42] as well as works on Himalayan species of Allium.[43] On returning from the war, Stearn and his new wife, Eldwyth Ruth Stearn, were obliged to live in the Lindley Library for a while till they found a more permanent home, due to the acute housing shortage in London.[9][12]

Natural History Museum (1952–1976)

From the Lindley Library, Stearn (see 1950 Photograph) moved to the Botany Department at the Natural History Museum, South Kensington[lower-alpha 6] in 1952, and by the time he retired in 1976, he was the Senior Principal Scientific Officer there. He had now achieved his aim of becoming a research scientist, despite lack of formal qualifications, enabling him to spend more of his time collecting and studying plants.[9] During this time the museum was undergoing steady expansion, with new staff and programmes. At the museum he was put in charge of Section 3 of the General Herbarium (the last third of the Dicotyledons in the Bentham & Hooker system, i.e., Monochlamydae)[lower-alpha 7] and floristic treatment of the regions of Europe, Jamaica, the United States, Australia and Nepal, including work on the museum's Flora of Jamaica[44] and the Nepal flora he started work on during the war.[41][16] Seven volumes of the Flora of Jamaica had appeared prior to the Second World War. Although the project was revived after the war, and Stearn carried out six months of field work in Jamaica, it never came to fruition; no further volumes appeared. In Jamaica, Stearn followed in the footsteps of Sir Hans Sloane (1660–1753), whose collection had been left to the Natural History Museum.[9][45] Stearn's generic work at the museum concentrated on Allium,[46] Lilium and Paeonia.[5] He continued to travel widely, with field work in Europe (particularly Greece), Australia, and the United States,[9] and published 200 papers during his twenty-four years at the museum, and although the library was not his responsibility, he spent much time there adding written notes to many of the critical texts.[23]

While at the museum, Stearn became increasingly involved in the work of the Linnean Society during his Kensington years. He was also offered the George A. Miller professorship of botany at the University of Illinois (1966), but felt he would be unable to leave his commitments in London.[1][2] At the time of his retirement in 1976, he was still using a fountain pen as his only means of communication and scholarship, a fact commemorated by his retirement present of a Mont Blanc pen capable of writing for long periods without refills.[23]

Retirement (1976–2001)

Following his retirement on 30 November 1976 he continued to work, both at the museum and at the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew, where his home at 17 High Park Road, Kew Gardens, Richmond (see image), gave him access to the herbarium and library, a short bicycle trip away.[8] Indeed, 35 percent of his total publications appeared in the quarter century of his retirement.[47] He was commissioned to write a history of the museum for its centenary (1981),[48] although he did so with some difficulty, due to deadlines and budget constraints.[49] The task, which took three years, was made more difficult for him by the museum's decision to censor his critical comments.[23] He continued his association with the Lindley Library all his life, being an active committee member[9] and regularly attended RHS flower shows even after he was barely able to walk.[5]

Sojourn in Greece

As a student of the classics he was passionate about Greece, its mountains and plants (such as Paeonia)[50] and all things Greek, both ancient and modern.[51] The Stearns had formed a friendship with Constantine Goulimis and Niki and Angelos Goulandris, founders of the Goulandris Museum of Natural History[52] in Kifissia, Athens. Stearn first met the Goulandris' in 1967, and offered practical help with their museum. He also stayed with them when he and his wife visited Greece.[13] Niki Goulandris illustrated both Wild Flowers of Greece that Goulimis and Stearn wrote in 1968,[53] as well as his Peonies of Greece (1984).[54][55] The latter work typified Stearn's encyclopedic approach, including topics such as mythology and herbalism in addition to taxonomy.[56] Stearn then took on the editorship of Annales Musei Goulandris,[57] the scientific journal of the museum (1976–1999), succeeding Werner Greuter, the first editor, having been instrumental in getting the journal launched in 1973.[1][2] Eldwyth Ruth Stearn took on the job of compiling the indexes. When he retired from this position he was 88, and was succeeded by John Akeroyd.[13][58] He was a liberal contributor to the journal, and during this time he and Eldwyth Ruth Stearn undertook their translation of The Greek Plant World in Myth, Art, and Literature (1993).[59]

Societies and appointments

Stearn was a member of the Linnean Society[lower-alpha 8] for many years, becoming a fellow as early as 1934. He served as botanical curator 1959–1985, council member 1959–1963 and as vice-president 1961–1962 and president 1979–1982,[15][60] producing a revised and updated history of the society in 1988.[61] He also served as president of the Garden History Society and the Ray Society (1975–1977). The Royal Horticultural Society had made him an honorary fellow in 1946 and in 1986 he became a vice-president. Stearn became a member of the Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland (BSBI) in 1954,[62] joining the Maps Committee the following year to prepare their Atlas of the British Flora (1962).[63][64] He remained on that committee till 1968, when it became the Records Committee. For 40 years he was the BSBI referee for Allium.[16] While at the Lindley Library, he became a founding member of the Society for the Bibliography of Natural History (later, the Society for the History of Natural History) in 1936, was one of its most active publishing members based on his cataloguing work at the library,[12] and published a history of the society for their 50th anniversary in 1986.[8][65] Other societies on which he served include the British Society for the History of Science (vice-president), the British Society for the History of Medicine (Council), the Garden History Society (president 1977–1982)[8][9] and was a corresponding member of the Botanical Society of America.[66]

Stearn was appointed Sandars Reader in Bibliography, University of Cambridge in 1965 and from 1977 to 1983 he was visiting professor at Cambridge University's Department of Botany, and also Visiting Professor in Botany at Reading University 1977–1983, and then Honorary Research Fellow (1983–).[67] He was also a fellow of the Institute of Biology (1967) and was elected an Honorary Fellow of Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge in 1968.[1]

Work

William Stearn was the author of nearly 500 publications, including his autobiography.[68][lower-alpha 9] These included monographs, partial floras, books on botanical illustration, scholarly editions of historical botanical texts, dictionaries, bibliographies and botanical histories.[5]

Early years

.jpg.webp)

During Stearn's initial four years in Cambridge (1929–1933), he published twenty-four papers, predominantly in the Gardeners' Chronicle and Gardening Illustrated and the Journal of Botany,[1][9] his first in 1929. While working as a gardener's boy during school holidays he had observed a specimen of Campanula pusilla (Campanula cochleariifolia) with a distorted corolla. He then described and published the first appearance of the causative agent, the mould Peronospora corollaea, in Britain, using the facilities of the Botany library.[8][69]

At the Botanic Garden he developed a special interest in Vinca, Epimedium, Hosta and Symphytum, all of which he published monographs on.[70] A series of botanical publications followed,[71] starting with a new species of Allium (A. farreri Stearn, 1930).[72][lower-alpha 10] Stearn repeatedly returned to the genus Allium, and was considered a world expert on it; many species bear his name.[16][56][lower-alpha 11] 1930 would also see his first bibliographic work, on the botanist Reginald Farrer,[75][76] whom he named Allium farreri after,[76] and also described Rosa farreri (1933)[77] and other species named after Farrer. It was while he was compiling Farrer's works in 1930 that he came across the latter's work, The English Rock-Garden (1919)[78] and its account of Barren-worts (Epimedium), and kindled a lifetime interest in the genus.[24] From 1932, he produced a series of papers on this genus,[79] studying it at Cambridge, Kew and Paris. It became one of the genera which he was best known, and many species of which now bear his name.[80][24] Epimedium and the related woodland perennial Vancouveria (Berberidaceae) would be the subject of his first monograph (1938)[81] and were genera to which he would return at the end of his life.[82] At the time the taxonomy of this genus was very confused, and with the help of the Cambridge Herbarium he obtained specimens from all over Europe to produce a comprehensive monograph.[11] The work was so thorough that it was mistakenly considered a doctoral thesis by other botanists. He also began a series of contributions to the catalogue of the Herbarium, together with Gilmour and Tutin.[2]

Later work

After moving to London, Stearn produced a steady output of publications during his years at the Royal Horticultural Society's Lindley Library (1933–1952). These covered a wide range of topics from bibliography to plant nomenclature, taxonomy and garden plants, with a particular emphasis on Vinca, Epimedium and Lilium.[83] Within two years of joining the library in 1933, he had produced his first major monograph, Lilies (1935),[84] in collaboration with Drysdale Woodcock and John Coutts.[56][lower-alpha 12] This text, in an expanded and revised edition, as Woodcock and Stearn's Lilies of the World (1950)[87] became a standard work on the Liliaceae sensu lato.[56] While at the library he also continued his collaboration with his Cambridge colleagues, publishing catalogues of the Herbarium collections,[88] including the Catalogue of the Collections of the Herbarium of the University Botany School, Cambridge (1935).[89] The second task imposed on him at this time involved the RHS role in maintaining revision of the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature (see Botanical taxonomy).

After his return to London in 1946, at the end of the Second World War, a number of major publications ensued, including Lilies of the World in 1950.[12] The RHS also imposed two major tasks on their librarian. In 1950, Frederick Chittenden, a previous director of RHS Wisley and Keeper of the Library, died leaving unfinished the four volume RHS Dictionary of Gardening that the society had commissioned from him before the war. The war had interrupted the work as many of the expected contributors were unavailable.[12] Stearn, together with Patrick Synge, the RHS Publications Editor, undertook to complete the work, particularly volume IV (R–Z), a task he completed within six months, with 50 new articles. The finished work was published in 1951[90] and not only did he undertake the role of editing this large work but his contributions covered 50 genera, 600 species and complex identification keys such as Solidago and Viola.[5] Since Stearn's entries in volume IV extended from Soldanella to Zygotritonia, he would jest that he was but "a peculiar authority on plants from 'So-' onwards". He issued a revised version in 1956 with Synge in which he added a further 86 articles.[91] His recollection of this task was that he acquired "that occupational hazard of compilers of encyclopaedias", encyclopedic knowledge.[5]

Many of Stearn's collaborative works used his bibliographic skills. While his genus monographs largely concentrated on Mediterranean flora, notably Epimedium,[82] Allium[92][93] and Paeonia,[94] he was also the author of species articles both popular and technical as well as a number of classical treatises.[18] In addition he produced floristic treatments of a number of regions such as Jamaica[95] and Nepal.[41] He also contributed to many national Florae as diverse as Bhutan[96] and Greece,[50] as well as major regional florae including the Flora Europaea[97] and European Garden Flora.[98]

While his output covered a wide range of topics, he is best known for his contributions to botanical history, taxonomy, botanical bibliography, and botanical illustration. Botanical Latin (four editions 1966–1992),[99] is his best known work,[15][21] having become a standard reference and described as both the bible of plant taxonomists and a philological masterwork.[5] It was begun during the war years and the first edition was basically a guide to Latin for botanists with no or limited knowledge of the language, which he described as a "do-it-yourself Latin kit" for taxonomists.[21] Later, the work evolved into an etymological dictionary,[100] but then Stearn learned that such a work had already been published in the Netherlands before the war. He then continued to expand it with the assistance of his wife and son, systematically collecting botanical terms from botanical texts. It is said that only he could have written this work, which explains not just the derivation of plant names but also the philological principles involved in forming those names.[9][21] The work is considered responsible for the continued survival of Latin as the lingua franca of botany.[5] In addition to this seminal text, he frequently delighted in the illumination that the classics could add to understanding plants and plant lore, such as his Five Brethren of the Rose (1965).[101]

His best known popular work is his Dictionary of Plant Names, which found its way into the libraries of most horticulturalists.[102] One of the focuses of his work at the Natural History Museum was the flora of the Caribbean, where he carried out field work.[11] Stearn continued to return to the Cambridge Botanic Garden, cared for his own garden and worked with the RHS to become an authority on horticulture as well as botany.[1] William Stearn collaborated with his wife, Eldwyth Ruth Stearn, on a number of his most important works, including Botanical Latin[103] and Dictionary of Plant Names and translating German botanical history into English.[104] Just before his death he completed a revision of his original Epimedium monograph.[82][56]

Botanical history

.png.webp)

William Stearn wrote extensively on the history of botany and horticulture,[83][105] from Ancient Greece to his own times. He collected together J. E. Raven's 1976 J. H. Gray Lectures,[lower-alpha 13] editing and annotating them as Plants and Plant Lore in Ancient Greece (1990).[107][lower-alpha 14] In 1993, he and Eldwyth Ruth Stearn translated and expanded Baumann's Die griechische Pflanzenwelt in Mythos, Kunst und Literatur (1986) as The Greek Plant World in Myth, Art, and Literature.[104]

Stearn compiled a major work on the life of John Lindley[36] and produced an edited version of the classic book on herbals by Agnes Arber,[108] one of the influences of his Cambridge years, and whose obituary he would later write for The Times.[109] He also wrote a number of histories of the organisations he worked with[48][61] as well as a number of introductions and commentaries on classic botanical texts such as John Ray's Synopsis methodica stirpium Britannicarum (1691),[110][lower-alpha 15] together with historical introductions to reference books, including Desmond's Dictionary of British and Irish Botanists (1994).[111][112]

In his Botanical Gardens and Botanical Literature in the Eighteenth Century (1961), Stearn provides some insight into his interpretation of botanical history:

The progress of botany, as of other sciences, comes from the interaction of so many factors that undue emphasis on any one can give a very distorted impression of the whole, but certainly among the most important of these for any given period are the prevailing ideas and intellectual attitudes, the assumptions and stimuli of the time, for often upon them depends the extent to which a particular study attracts an unbroken succession of men of industry and originality intent on building a system of knowledge and communicating it successfully to others of like mind.[113]

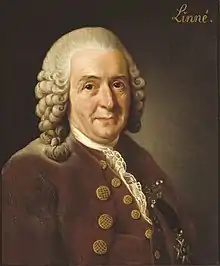

Linnaeus

Stearn's historical research is best known for his work on Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778), which he began while at the Natural History Museum, and which won him a number of awards at home and abroad. Between 1953 and 1994 he produced more than 20 works describing Linnaeus' life and work.[47][114][115]

Of Stearn's writings on Linnaeus, the most well known is his edition of the 1753 Species plantarum, published in facsimile by the Ray Society in 1957,[116] for which he wrote both a 176-page introduction and an appendix.[117][118][lower-alpha 16] Concerned that Linnaeus' methods were imperfectly understood by his contemporaries, Stearn wrote that his introduction "provided concisely all the information about his Linnaeus' life, herbaria, publications, methodology etc. which a botanical taxonomist needs to know". The Times stated that no other botanist possessed the historical knowledge and linguistic skills to write, what is considered one of the classic studies of the Swedish naturalist and a highpoint of 20th century botanical scholarship. Subsequently, Stearn became a recognised authority on Linnaeus.[5] Stearn produced similar introductions to a number of other editions of Linnaeus' works, including Genera Plantarum,[119] Mantissa plantarum[120] and Flora Anglica.[21][lower-alpha 17] Later, he would produce a bicentenary guide to Linnaeus (1978) for the Linnean Society.[1][7][124]

Although Stearn spent much of his life studying and writing about Linnaeus, he did not admire the man's character, describing him as mean—"a jealous egoist, with a driving ambition". When asked which botanists in history he did admire, he cited John Lindley, Carolus Clusius (1526–1609) and Olof Swartz (1760–1818).[9]

Botanical taxonomy

Stearn made major contributions to plant taxonomy and its history.[125] In 1950 the Seventh International Botanical Congress was held in Stockholm, and the RHS would have been represented by Chittenden, but he had been taken ill. Bowles then arranged for Stearn and Gilmour to represent the society in his stead.[13][lower-alpha 18] The congress appointed a special committee to consider nomenclatural issues related to cultivated plants, which became known as the Committee for the Nomenclature of Cultivated Plants (the "Stockholm Committee"), with Stearn as secretary (1950–1953).[9][lower-alpha 19] Stearn then proposed an International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants (the "Cultivated Code"), producing the first draft that day. The code was accepted in principle by the committee, conditional on its approval by a parallel committee of the International Horticultural Congress (the Horticultural Nomenclature Committee), which would next meet in London in 1952 (the "London Committee").[83] Later that year Stearn was also appointed secretary of the London Committee[126][lower-alpha 20] so that he now represented both organisations. The two committees then met jointly on 22–24 November 1951 at the RHS building in London to draft a final joint proposal that was published by Stearn as secretary of an editorial committee and adopted by the 13th International Horticultural Congress the following year.[127]

The resulting code was formulated as a supplement to the existing International Code of Botanical Nomenclature.[128][129][lower-alpha 21] Stearn introduced two important concepts, the terms "cultivar" and "grex". Cultivar, a term first proposed by L. H. Bailey in 1923,[130] refers to a distinctive genus or species variety raised or maintained in cultivation, such as Euphorbia dulcis "Chameleon". Grex (Latin for "flock" or "herd") refers to a group of hybrids of common parentage, such as Lilium Pink Perfection Group.[83] These concepts contributed a similar clarity to the nomenclature of garden or agricultural plants that Linnaeus had brought to the naming of native plants two centuries earlier.[5] Stearn continued to play an active part in the International Botanical Congresses over many years, where he was remembered for his rhetorical persuasion on nomenclatural matters.[131] He was also a pioneer in the application of computer-aided technology to (numerical taxonomy), as in his work on Columnea (1969).[15][132]

Botanical bibliography

Motivated by his interest in botanical history and taxonomy, Stearn devoted a considerable part of his output to botanical bibliography, including numerous papers and catalogues establishing the exact publication dates of books on natural history, particularly from the early nineteenth century, including William Herbert's work on Amaryllidaceae (1821, 1837)[128][8][133] and complete bibliographies of botanists such as John Gilmour (1989).[134] At the RHS library he transformed the minimalist card indexing by introducing British Museum rules and adding extensive bibliographic information.[12] He quickly realised that one of the major deficits in contemporary taxonomic nomenclature was a lack of precise dates of all the names, and set about rectifying this over a fifteen-year period, resulting in 86 publications, which was a major step in stabilising nomenclature. The importance of this lay in the rules of botanical nomenclature, which gives botanical names priority based on dates of publication.[12] He considered his most important contribution in this regard to be his elucidation[135] of the dating of the early 19th century collection of studies of Canary Islands flora by Webb and Berthelot (1836–1850).[136] Another important work from this period was on Ventenat's Jardin de la Malmaison (1803–1804), also published in the new Journal of the Society for the Bibliography of Natural History.[137][12] In a number of instances his contributions to others' work went unacknowledged, particularly when he was younger, even though his introductions (often with the title "Revised and enlarged by W. T. Stearn") could be as lengthy as the texts they preceded.[138][lower-alpha 22] His contributions to botanical bibliography and in particular the correct interpretation of historical texts from Linnaeus to Arber are considered of central importance to the field of taxonomy.[140]

Botanical illustration

Within a few years after Stearn returned from the war, his Art of Botanical Illustration (1950)[141][142] was published, remaining the standard work on the subject to this day. There was, however, some bibliographic confusion[12] – Collins, the publisher, had planned a book on botanical art for its New Naturalist series, but mistakenly commissioned both Stearn and the art historian Wilfred Blunt independently to produce the work. After the error was discovered the two decided to collaborate; Blunt wrote the work while Stearn edited and revised it. When it was published, Blunt's name was on the title page, while Stearn was only acknowledged in the preface.[lower-alpha 24] The omission was not rectified till he prepared the second edition in 1994, although the preface reveals Stearn's extensive contribution.[7][12]

His continuing interest in botanical illustration led him to produce work on both historical[144] and contemporary artists,[145][146] including the Florilegium of Captain Cook and Joseph Banks from their first voyage (1768–1771) to the Pacific on the Endeavour,[147] the similar account of Ferdinand Bauer's later botanical expedition to Australia with Matthew Flinders on the Investigator (1801–1803),[148] and the work of illustrator Franz Bauer (the brother of Ferdinand).[149][150] Stearn's studies of Ferdinand Bauer's Flora Graeca (1806–1840) enabled him to combine his passion for Greece with that of illustration.[51][151] Other illustrators of this period that he wrote about included William Hooker.[152][12][lower-alpha 25]

Awards

William Stearn received three honorary doctorates during his lifetime, from Leiden (D.Sc. 1960),[lower-alpha 26] Cambridge (Sc.D. 1967), and Uppsala (Fil.Dr. 1972).[11][15] He was the Masters Memorial Lecturer, Royal Horticultural Society in 1964. In 1976 the Linnean Society awarded him their Gold Medal[lower-alpha 27][155] for his contributions to Linnean scholarship[117] and taxonomic botany.[60][156] In 1985 he was the Wilkins Lecturer of the Royal Society, entitled Wilkins, John Ray, and Carl Linnaeus.[157] In 1986 he received the Founder's Medal of the Society for the History of Natural History and in 1993 he received the Engler Gold Medal from the International Association for Plant Taxonomy.[158][lower-alpha 28] The Royal Horticultural Society awarded him both their Veitch Memorial Medal (1964) and Victoria Medal of Honour (VMH, 1965). In 2000 he received the Asa Gray Award, the highest honour of the American Society of Plant Taxonomists.[18] Stearn was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in the 1997 Birthday Honours for services to horticulture and botany.[159]

He was well regarded in Sweden for his studies on Linnaeus, and possessed a good grasp of the language. In addition to his honorary doctorate from Uppsala, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarded him their Linnaeus Medal in 1972, he was granted the title of Commander of the Swedish Order of the Star of the North (Polar Star) in 1980 and admitted to membership of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1983. Stearn was also elected to membership of the Swedish Linnaeus Society.[21]

Legacy

Stearn is considered a preeminent British botanist, and was once likened to botanical scholars such as Robert Brown, Darwin, the Hookers (William and Joseph) and Frans Stafleu.[2][7] He has been variously described as a Renaissance man,[20] a polymath,[153] "the modern Linnaeus",[160][161] "the great Linnaean scholar of our day", [162] "one of the world's greatest botanists"[163] and a giant among botanists and horticulturalists.[11] On his death, The Times noted his encyclopedic grasp of his field, stating that he was "acknowledged as the greatest botanical authority of the twentieth century".[5] One description that Stearn rejected, however, was "the complete naturalist"[lower-alpha 29] – an allusion to the title of his biography of Linnaeus.[165] His contribution to his field was far greater than his extensive bibliography suggests, since he was known for his input into many of his colleagues' work, leading Professor P. B. Tomlinson to observe "he left no tome unstearned".[56] The Society for the History of Natural History of which he was a founding member has created the William T. Stearn Student Essay Prize in his honour.[166]

Eponymy

Stearn is the botanical authority[167] for over 400 taxa that bear his name, such as Allium chrysonemum Stearn. Many plants have been named (eponymy) after him, including the orchid nothogenus hybrid ×Stearnara J. M. H. Shaw.[lower-alpha 30] A number of species have been designated stearnii after William Stearn, including:

- Allium stearnii Pastor & Valdés

- Berberis stearnii Ahrendt

- Epimedium stearnii Ogisu & Rix

- Justicia stearnii V.A.W. Graham

- Schefflera stearnii R.A.Howard & Proctor

In light of his work on Epimedium, a cultivar was named in his honour in 1988, Epimedium 'William Stearn'.[170][171]

Selected publications

- see Walters (1992b) and Heywood (2002)

- Arber, Agnes (1986) [1912; 2nd ed. 1938]. Stearn, William T. (ed.). Herbals: their origin and evolution. A chapter in the history of botany, 1470–1670 (3rd ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-33879-0.

- Stearn, William T. (2002a) [1938]. Green, Peter Shaw; Mathew, Brian (eds.). The genus Epimedium and other herbaceous Berberidaceae. (including the genus Podophyllum by Julian Shaw, illustrations by Christabel King) (Revised ed.). Kew: Royal Botanic Gardens. ISBN 978-1-84246-039-9.

- Rix, Martyn (February 2003). "The Genus Epimedium and other herbaceous Berberidaceae". Curtis's Botanical Magazine (Review). 20 (1): 58–63. doi:10.1111/1467-8748.t01-1-00371.

- Blunt, Wilfrid; Stearn, William (1994) [1950 Collins]. The art of botanical illustration: an illustrated history. New York City: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-27265-8.

- Stearn, William T. (1992) [1966 London: Nelson. 2nd ed. 1973. 3rd ed. 1983]. Botanical Latin: history, grammar, syntax, terminology and vocabulary (4th ed.). Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. ISBN 978-0-88192-321-6.

- Bacigalupi, Rimo (April 1967). "Botanical Latin. By William T. Stearn". Madroño (Review). 19 (2): 59–60.

- Eichholz, D. E. (March 1967). "William T. Stearn: Botanical Latin: History, Grammar, Syntax, Terminology and Vocabulary. Pp. xiv+566; 41 ill. Edinburgh: Nelson, 1966. Cloth, 105s. net". The Classical Review (Review). 17 (1): 120. doi:10.1017/S0009840X00323654. S2CID 161335091.

- Weresub, Luella K. (January 1967). "Botanical Latin, by William T. Stearn". Mycologia (Review). 59 (1): 183–185. doi:10.2307/3756953. JSTOR 3756953.

- Stearn, William T. (1981). The Natural History Museum at South Kensington: a history of the museum 1753–1980. London: Natural History Museum. ISBN 978-0-565-09030-2.

- Tucker, Denys (28 May 1981). "Cathedral of Natural History: The Natural History Museum at South Kensington. A history of the British Museum (Natural History) 1753–1980, by William T. Stearn". New Scientist (Review). 90 (1255): 571.

- Stearn, William T. (2002b) [1992]. Stearn's dictionary of plant names for gardeners: a handbook on the origin and meaning of the botanical names of some cultivated plants. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. ISBN 978-0-88192-556-2.

- Rae, David A. H. (26 April 2010). "Stearn's Dictionary of Plant Names for Gardeners – a handbook on the origin and meaning of the botanical names of some cultivated plants. W.T. Stearn. Cassell Publishers Limited, London. Pp 363. ISBN 0-304-34149-5. £16.99". Edinburgh Journal of Botany (Review). 50 (1): 122. doi:10.1017/S0960428600000779.

- Stearn, William T., ed. (1999). John Lindley (1799–1865): gardener, botanist and pioneer orchidologist: Bi-centenary celebration volume. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors Club & Royal Horticultural Society. ISBN 978-1-85149-296-1.

- Green, Peter S. (November 1999). "William T. Stearn: John Lindley 1799–1865. Gardener-Botanist and Pioneer Orchidologist". Curtis's Botanical Magazine (Review). 16 (4): 301–302. doi:10.1111/1467-8748.00234.

See also

- History of botany

- Cambridge Botanic Garden

Notes

- Opened in 1908, closed in 2006 and demolished in 2007, the site is now occupied by the Cambridge Manor Care Home[3][4]

- He later said "I was interested as much in birds and insects as in plants but I think it was my interest in gardening which made me choose plants. I gardened at home and knew the botanic garden at Cambridge well."[10]

- The oldest bookshop in Britain[14]

- Anemone hupehensis var. japonica (Thunb.) Bowles & Stearn, now considered a synonym of Anemone scabiosa H. Lév. & Vaniot[28]

- "When I had to sit for hour after hour, day after day, staring at the sky from a Royal Air Force ambulance awaiting planes which, fortunately rarely crashed, I filled in time by extracting the descriptive epithets from a series of Floras lent me by the Lindley Library of the Royal Horticultural Society in the hope of producing some day an etymological dictionary of botanical names"[40]

- The Natural History Museum was then still called the British Museum (Natural History)

- The system by which the herbarium was arranged when the museum's collections were moved from Bloomsbury to Kensington in 1881

- named after the 18th-century Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus

- Publications are numbered consecutively from 1 (1929) to 499 (1999)[18]

- In 1950 he came to realise this was not a separate species but a variety of Allium cyathophorum and thus renamed it Allium cyathophorum var. farreri (Stearn) Stearn.[73][74]

- Stearn produced 21 publications on Allium

- Lilies was published under Woodcock and Coutts' names but was largely written by Stearn.[85][56] The copy in the Lindley Library belonged to Fred Stoker of the RHS Lily Committee, who had reviewed it. In it he wrote "Nominally by H Drysdale Woodcock KC and J Coutts VMH...but principally by W. T. STEARN whose text I have read in great part".[86]

- Faculty of Classics lectures at Cambridge, named for the Revd. Canon Joseph Henry Gray (1856–1932), a classical scholar at Queens' College[106]

- Later enlarged and reissued as a book[106]

- Ray's Synopsis methodica stirpium Britannicarum of 1691 was for long a major source of information on British plants, and an important source for Linnaeus' later work on this subject

- Volume 1 (1957) An introduction to the Species plantarum and cognate botanical works of Carl Linnaeus, pp. 1–176. Volume 2 (1959) An appendix to the Species plantarum of Carl Linnaeus, pp. 1–147 includes notes on the illustrations by Stearn with an index to species and genera[21]

- In 1973 Stearn produced an edited work for the Ray Society dealing with the flora of the British Isles.[121] This consisted of two works, the posthumous third edition of John Ray's Synopsis methodica stirpium Britannicarum (1724),[110] together with Linnaeus' Flora Anglica (1754)[122] which was based on the former work[123]

- Stearn later provided a detailed account of this in an address to the International Horticultural Congress in 1986[83]

- This committee was chaired by Wendel Holmes Camp (USA), who would also chair the upcoming joint committee of the Botanical and Horticultural Congresses in London in 1951

- Stearn succeeded Chittenden in this position, upon the latter's death. The Horticultural Nomenclature Committee was renamed the International Committee on Horticultural Nomenclature and Registration in 1951

- In 1952 Stearn described the history of the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature from 1864[126]

- Such as F. C. Stern's A Study of the Genus Paeonia (1946)[2][139]

- Engraving by Daniel MacKenzie (1770–1780)

- Blunt states he received "some 30 foolscap pages of comments, almost all of which have been incorporated, often indeed verbatim, in my text".[143] Stearn also provided the bibliography

- William Hooker (1779–1832) the illustrator should be distinguished from William Hooker (1816–1840) the botanist

- 11 November 1960. Promoted by Professor Jan van Steenis, whose citation mentioned, inter alia, Stearn's "remarkable rise to a lofty scientific level by exploiting with energy, perseverance, caution and a rare combination of talent and character – under difficult and often disheartening circumstances.[153] At which occasion he delivered the lecture "The Influence of Leyden on Botany in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries"[154]

- Stearn was the last recipient of this medal under this name. It is no longer made of gold and is now called the Linnean Medal, and not to be confused with the rarely awarded Linnean Gold Medal[61]

- At the XVth International Botanical Congress, Yokohama, Japan 29 August 1993[18]

- "I note you are giving a lecture relating to me as 'a Complete naturalist' which I am most certainly far from being: the only person to whom that distinction could have been given in modern times was Charles Raven"[164]

- Named by Julian Shaw, Orchid Registrar, Royal Horticultural Society 2002[168][169]

References

- Prance 2014.

- Heywood 2002.

- Cambridge 2000 2016, Milton Road Junior School

- Geograph 2011, Demolition of Milton Street School

- Times 2001.

- Heywood 2002; Times 2001; Barker 2001.

- Daily Telegraph 2001.

- Festing 1978.

- Barker 2001.

- Country Life 1996.

- Prance 2001.

- Elliott 2002.

- Akeroyd 2006a.

- CUP 2017.

- Walters 2001.

- Robson 2001.

- Walters 1992b.

- Iltis 2001.

- Temple 2010.

- Moody 2002.

- Desmond 2002.

- Moody 2002, p. 44.

- Humphries 2002.

- Rix 2003.

- Prance 2014; Heywood 2002; Robson 2001.

- Bowles 1952.

- Bowles & Stearn 1947.

- TPL 2013, Anemone hupehensis var. japonica

- Rudy 2004, p. 1.

- Allan 1973.

- Stearn 1955.

- Prance 2014; Walters 2001; Buchan 2007.

- Lucas 2008.

- Herbarium 2016a, Lindley Collection

- Stearn 1992, p. vii.

- Stearn 1999a.

- Elliott 1999.

- Elliott 2009, pp. 7, 9.

- Prance 2014; Daily Telegraph 2001; Walters 2001.

- Stearn 1992, p. vi.

- Hara et al. 1978–1982.

- Blatter & Millard 1954.

- Prance 2014; Heywood 2002; Stearn 1994.

- Fawcett & Rendle 1910–1939.

- Frodin 2001, Jamaica pp. 289–29-

- Stearn 1978.

- Nelson & Desmond 2002.

- Stearn 1981.

- Prance 2014; Walters 2001; Iltis 2001.

- Stearn & Landström 1991.

- Stearn 1976a.

- GMNH 2016.

- Goulimis & Stearn 1968.

- Barker 2001; Stearn & Davis 1984.

- Haines 2001, Niki Goulandris p. 116

- Mathew 2002.

- GMNH 2016, Annales Musei Goulandris

- Akeroyd 2006.

- Daily Telegraph 2001; Walters 1992b; Baumann 1993.

- The Linnean Society 1976, p. 299.

- Gage & Stearn 1988.

- BSBI 2016.

- Perring & Walters 1962.

- Robson 2001, p. 124.

- Stearn 2007.

- BSA 2017, Corresponding Members

- Heywood 2002; Walters 2001; Daily Telegraph 2001.

- Nelson & Desmond 2002; The Linnean Society 1976; The Linnean Society 1992.

- Stearn 1929.

- Avent 2010, p. 10.

- The Linnean Society 1976.

- Stearn 1930.

- WCLSPF 2015, var. farreri

- Stearn 1955a.

- Stearn 1930a.

- Nelson & Desmond 2002, pp. 144, 146, 148.

- Stearn 1933.

- Farrer 1919.

- Nelson & Desmond 2002, pp. 144–146.

- Avent 2010.

- Stearn 1938.

- Stearn 2002a.

- Stearn 1986.

- Woodcock & Coutts 1935.

- The Linnean Society 1976, p. 300.

- Elliott 2007.

- Woodcock & Stearn 1950.

- Gilmour & Stearn 1932.

- Heywood 2002; Festing 1978; Walters 1992b.

- Huxley et al. 1992.

- Prance 2014; Daily Telegraph 2001; Prance 2001.

- Stearn 1944.

- Stearn 1981a.

- Stearn & Davis 1984.

- Stearn 1959b.

- Stearn 1994.

- Stearn 1964; Stearn 1972; Stearn 1980.

- Stearn & Campbell 1986; Stearn 1989; Stearn 1995.

- Stearn 1992.

- Walters 2001; Walters 1992b; Iltis 2001.

- Stearn 1965a.

- Prance 2014; Daily Telegraph 2001; Stearn 2002b.

- Stearn 1992, Front matter.

- Baumann 1993.

- Stearn 1965.

- Raven 2000.

- Stearn 1990a.

- Arber 1986.

- Stearn 1960.

- Ray 1724.

- Prance 2001; Robson 2001.

- Desmond 1994, Historical Introduction pp. xiii–xix

- Stearn 1961.

- Stearn 1959a.

- Stearn 1958.

- Ray Society 2017.

- Linnaeus 1753.

- Ray Society 2017, Linnaeus Species Plantarum 1753 Vols. 1 and 2

- Linnaeus 1754.

- Linnaeus 1767–1771.

- Ray Society 2017, John Ray, Synopsis Methodica Stirpum Britannicarum

- Linnaeus & Grufberg 1754.

- Stearn 1973a.

- Stearn & Bridson 1978.

- Stearn 1973.

- Stearn 1952a.

- Heywood 2002; Stearn 1953; Stearn 1952b.

- Stearn 1952.

- Wyman 1956, p. 65.

- Bailey 1923, vol. I pp. 116ff.

- Heywood 2002; Prance 2014; Daily Telegraph 2001.

- Stearn 1969.

- Goodwin, Stearn & Townsend 1962.

- Stearn 1989a.

- Stearn 1937.

- Webb & Berthelot 1836–1850.

- Stearn 1939; Ventenat 1803–1804.

- Prance 2014; Heywood 2002; Mathew 2002.

- Stern 1946.

- Stafleu & Cowan 1985, p. 851

- Blunt & Stearn 1994.

- Blunt 2001.

- Blunt & Stearn 1994, Preface p. xxv

- Sitwell 1990.

- Stearn & Brickell 1987.

- Stearn 1990.

- Blunt & Stearn 1973.

- Stearn 1976.

- Stewart & Stearn 1993.

- Stearn 1960a.

- Stearn 1967.

- Stearn & Roach 1989.

- Festing 1978, p. 410.

- Stearn 1962.

- "The Linnean Gold Medal". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 8 (4): 356–357. December 1976.

- Manton 1976.

- Stearn 1986a.

- IAPT 2016, The Engler Medal in Gold

- "No. 54794". The London Gazette (Supplement). 13 June 1997. p. 9.

- Stafleu & Cowan 1985, p. 850

- Buchan 2007; Bourne 2010.

- Cox 2003, p. xxv.

- Carmichael 2007, p. 43.

- Walters 1992b, p. 442.

- Walters 1992b; Blunt 2001; Walters 1992a.

- SHNH 2016, William T. Stearn Student Essay Prize

- Plantlist 2016.

- Shaw 2002.

- RHS 2016, New orchid hybrids Sept – Nov 2002

- Avent 2010, p. 17.

- RHS 2016, Epimedium 'William Stearn'

- International Plant Names Index. Stearn.

Bibliography

General books, articles and chapters

Books

- Allan, Mea (1973). E. A. Bowles & his garden at Myddelton House [1865–1954]. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-10306-5.

- Boisset, Caroline, ed. (2007). Lilies and related plants. 2007–2008 75th Anniversary Issue (PDF). London: Royal Horticultural Society Lily Group. ISBN 978-1-902896-84-7.

- Bowles, Edward Augustus (1952) [1924]. A handbook of Crocus and Colchicum for gardeners (2nd ed.). London: Van Nostrand.[lower-alpha 1]

- Buchan, Ursula (2007). Garden people: the photographs of Valerie Finnis. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-51353-8. (see Valerie Finnis)

- Cox, E. H. M. (1930). The plant introductions of Reginald Farrer. London: New Flora and Silva Ltd.

- Cullen, James; Knees, Sabina G.; Cubey, H. Suzanne Cubey, eds. (2011) [1984–2000]. The European Garden Flora, Flowering Plants: A Manual for the Identification of Plants Cultivated in Europe, Both Out-of-Doors and Under Glass. 5 vols (2nd ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Farrer, Reginald (1919). The English Rock Garden 2 vols. London: Jack.

- Fawcett, William; Rendle, Alfred Barton (1910–1939). Flora of Jamaica, containing descriptions of the flowering plants known from the island. 7 vols. London: Natural History Museum.

- Frodin, David G. (2001) [1984]. Guide to Standard Floras of the World: An Annotated, Geographically Arranged Systematic Bibliography of the Principal Floras, Enumerations, Checklists and Chorological Atlases of Different Areas (2nd ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-42865-1.

- Green, P. S., ed. (1973). Plants, Wild and Cultivated: A Conference on Horticulture and Field Botany. September 1972. Faringdon: Classey. ISBN 978-0-900848-66-7.

- Haines, Catherine M. C. (2001). International Women in Science: A Biographical Dictionary to 1950. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-090-1.

- Hunt, Rachel McMasters Miller; Quinby, Jane; Stevenson, Allan (1958–1961). Catalogue of botanical books in the collection of Rachel McMasters Miller Hunt. 2 vols. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Hunt Botanical Library.

- Huxley, Anthony; Griffiths, Mark; Levy, Margot (1992) [1st ed. Frederick Chittenden and William Stearn. Oxford University Press 1951. 2nd ed. P.M. Synge (ed.) Oxford 1956]. The New Royal Horticultural Society Dictionary of Gardening (4 vols.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-47494-5.

- Noltie, Henry J. (1994). Flora of Bhutan: Including a Record of Plants from Sikkim and Darjeeling. v. 3, Pt. 1. Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. ISBN 978-1-872291-11-6.

- Perring, Franklyn; Walters, Stuart Max (1962). Atlas of the British flora. London: Botanical Society of the British Isles by Thomas Nelson. ISBN 9780715811993.

- Stern, F. C. (1946). A Study of the Genus Paeonia. Illustrated by Lilian Snelling. London: Royal Horticultural Society.

- Strid, Arne; Tan, Kit, eds. (1991). Mountain Flora of Greece, Volume 2. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-0207-0.

- Tutin, T. G.; et al., eds. (1964–1980). Flora Europaea. 5 vols (PDF). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 26 December 2016. (see Flora Europaea)

- Ventenat, É. P. (1803–1804). Jardin de la Malmaison (in French). Paris: Crapelet.

- Webb, Philip Barker; Berthelot, Sabin (1836–1850). Histoire naturelle des Iles Canaries. Paris: Béthune.

- Woodcock, H. B. D.; Coutts, J. (1935). Lilies: Their Culture and Management. Including a complete descriptive list of species. London: Country Life. (see front matter)

Historical sources

- Linnaeus, Carl (2003) [1751 Stockholm]. Linnaeus' Philosophia botanica. trans. Stephen Freer. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-856934-3. (see Philosophia Botanica)

- Linnaeus, Carl; Grufberg, Isaac Olofsson (1754). Flora Anglica, quam cum consens. experient. fac. medicae in Regia Academia Upsaliensi, sub praesidio viri nobilissimi atque experientissimi, Dn. Doct. Caroli Linnaei...publicae ventilationi offert Isaacus Olai Grufberg, Stockholmiensis. In Auditorio Carolino Majori D. (in Latin). Uppsala: Laur. Magnus Hojer. also available here

- Ray, John (1724) [1690]. Dillenius, Johann Jacob (ed.). Synopsis methodica stirpium Britannicarum: in qua tum notae generum characteristicae traduntur, tum species singulae breviter describuntur: ducentae quinquaginta plus minus novae species partim suis locis inseruntur, partim in appendice seorsim exhibentur: cum indice & virium epitome (editio tertia multis locis emendata, & quadringentis quinquaginta circiter speciebus noviter detectis aucta) [Synopsis of British plants] (in Latin) (3rd ed.). London: Gulielmi & Joaniis Innys.

Articles

- Akeroyd, John (2006). "Preface". Annales Musei Goulandris (11): 35–36.

- Avent, Tony (March 2010). "An overview of Epimedium". The Plantsman: 10–17.

- Bailey, Liberty Hyde (1923). "Various cultigens, and transfers in nomenclature". Gentes Herbarum. 1 (Part 3): 113–136.

- Bourne, Val (18 October 2010). "Garlic: savour the flavour". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- Elliott, Brent (December 2009). "The cultural heritage collections of the RHS Lindley Library". Occasional Papers from the RHS Lindley Library. 1.

- Lucas, A. M. (April 2008). "Disposing of John Lindley's library and herbarium: the offer to Australia". Archives of Natural History. 35 (1): 15–70. doi:10.3366/E0260954108000053.

- Rudy, Mark R. (2004). "Fall-blooming Anemone" (PDF). Plant Evaluation Notes (25).

- Shaw, J. M. H. (November 2002). "Sternara". Orchid Review. 110 (Suppl. 1248): 109.

- Wyman, Donald (26 December 1956). "The new International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants" (PDF). Arnoldia. 18 (12): 63–68.

- Temple, Ruth (2010). "Society News" (PDF). The Linnean. 26 (3): 3.

Chapters

- Carmichael, Cameron. A review of English language Monographs on the genus Lilium 1873–2006. pp. 35–46., in Boisset (2007)

- Cox, Paul Alan (2003). Introduction. pp. xv–xxv. ISBN 978-0-19-856934-3., in Linnaeus (2003)

- Elliott, Brent. The Lindley Library and John Lindley's library. pp. 175–190., in Stearn (1999)

- Elliott, Brent (2007) [1993]. A brief history of the RHS Lily Committee. pp. 28–35., in Boisset (2007)

Articles about Stearn

- Akeroyd, John (2006a). "William Thomas Stearn (1911–2001)". Annales Musei Goulandris (11): 9–16.

- "William T. Stearn, doyen of garden botanists". Country Life: 68. 24 October 1996.

- "Professor William Stearn". The Daily Telegraph (obituary). 10 May 2001.

- "William T. Stearn". The Times (obituary). 11 May 2001.

- Barker, Nicolas (15 May 2001). "William Stearn". The Independent (obituary). Archived from the original on 24 April 2008.

- Desmond, Ray (2002). "The Linnean Scholar" (PDF). The Linnean. 18: 41–43.

- Elliott, Brent (2002). "W. T. Stearn: The Royal Horticultural Society Years (1930–1952)" (PDF). The Linnean. 18: 34–36.

- Festing, Sally (10 August 1978). "Energy, perseverance and caution: Professor William Stearn, botanist extraordinary". New Scientist. 79 (1115): 410–412.

- Heywood, Vernon (June 2002). "William Thomas Stearn, CBE, VMH (1911–2001) – an appreciation". Archives of Natural History. 29 (2): NP–143. doi:10.3366/anh.2002.29.2.NP.

- Humphries, Chris (2002). "William T. Stearn: The Museum Years (1952–1976)" (PDF). The Linnean. 18: 34–40.

- Iltis, Hugh H. (January 2001). "William T. Stearn—Recipient of the 2000 Asa Gray Award". Systematic Botany. 26 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1043/0363-6445-26.1.1 (inactive 31 July 2022). JSTOR 2666651.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2022 (link) - Manton, Irene (December 1976). "The Linnean Gold Medal. Dr William Thomas Stearn, F.L.S". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 8 (4): 356–357. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1976.tb00254.x.

- Mathew, Brian (2002). "William Stearn – The Monographer" (PDF). The Linnean. 18: 32–34.

- Moody, James (2002). "W. T. Stearn – 20th Century Renaissance Man and Friend" (PDF). The Linnean. 18: 44–45.

- Prance, Ghillean T. (1 January 2001). "William Thomas Stearn (1911–2001)". Taxon. 50 (4): 1255–1276. doi:10.1002/j.1996-8175.2001.tb02620.x. JSTOR 1224755.

- Prance, Ghillean T. (May 2014). "Stearn, William Thomas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/75893. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Robson, N. K. B. (2001). "William Thomas Stearn" (PDF). Watsonia (obituary). 24: 123–124.

- Walters, S. M. (August 1992a). "A bouquet for the complete naturalist: a celebration of the 80th birthday of W. T. Stearn". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 109 (4): 435–436. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.1992.tb01441.x.

- Walters, S. M. (August 1992b). "W. T. Stearn: the complete naturalist". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 109 (4): 437–442. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.1992.tb01442.x.

- Walters, S. Max (6 June 2001). "William Stearn". The Guardian (obituary).

- "Stearn, William Thomas (1911–2001)". JStor Global Plants. JSTOR 000008088.

Stearn bibliography

- The Linnean Society (December 1976). "Publications by William T. Stearn on bibliographical, botanical and horticultural subjects, 1929–1976; a chronological list". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 8 (4): 299–318. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1976.tb00252.x.

- The Linnean Society (August 1992). "Publications by William T. Stearn on bibliographical, botanical and horticultural subjects, 1977–1991; a chronological list". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 109 (4): 443–451. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.1992.tb01443.x.

- Nelson, E. Charles; Desmond, Ray (June 2002). "Bibliography of William Thomas Stearn (1911–2001)". Archives of Natural History. 29 (2): 144–170. doi:10.3366/anh.2002.29.2.144.

- Stafleu, Frans A.; Cowan, Richard S. (1985). "Stearn, William Thomas". Taxonomic literature: a selective guide to botanical publications and collections with dates, commentaries and types. Vol. 5. Sal–Ste (2nd ed.). Utrecht: Bohn, Scheltema & Holkema. pp. 850–853. ISBN 9789031302246.

Works by Stearn cited

Articles

- Stearn, William T. (17 August 1929). "A new disease of Campanula pusilla (Peronospora corollae)". Gardening Illustrated. 51: 565.

- Stearn, William T. (1930). "A new Allium from China (A. farreri, sp. nov.)". Journal of Botany. 68: 342–343.

- Stearn, W. T. (1933). "Rosa farreri, Stapf. Farrer's "Threepenny-bit Rose"". Gardeners' Chronicle. Series 3. 94: 237–238.

- Stearn, William T. (15 February 1937). "On the dates of publication of Webb and Berthelot's "Histoire Naturelle des Îles Canaries"". Journal of the Society for the Bibliography of Natural History. 1 (2): 49–63. doi:10.3366/jsbnh.1937.1.2.49.

- Stearn, William Thomas (November 1938). "Epimedium and Vancouveria (Berberidaceae), a monograph". Journal of the Linnean Society of London, Botany. 51 (340): 409–535. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.1937.tb01914.x.

- Stearn, William Thomas (28 February 1939). "Ventenat's "Description des Plantes... de J. M. Cels," "Jardin de la Malmaison" and "Choix des Plantes"". Journal of the Society for the Bibliography of Natural History. 1 (7): 199–201. doi:10.3366/jsbnh.1939.1.7.199.

- Stearn, W. T. (1944). "Notes on the genus Allium in the Old World; its distribution, names, literature, classification and garden-worthy species". Herbertia. 11: 11–34.

- Stearn, William T. (November 1952). "William Herbert's "Appendix" and "Amaryllidaceae"". Journal of the Society for the Bibliography of Natural History. 2 (9): 375–377. doi:10.3366/jsbnh.1952.2.9.375.

- Stearn, William T. (1952b). "Proposed International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants. Historical Introduction". Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society. 77: 157–173.

- Stearn, W. T. (7 September 1952a). "International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants" (Address given by the Secretary of the International Committee on Horticultural Nomenclature and Registration at the opening meeting). Bromeliad Society International. Archived from the original on 18 April 2016. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- Stearn, William T. (July–August 1955). "E. A. Bowles (1885–1954), the man and his garden". Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society. 80: 317–326, 366–376.

- Stearn, W. T. (1955a). "Allium cyathophorum var. farreri". Curtis's Botanical Magazine. 170 (new series): tab. 252.

- Stearn, William T. (April 1959b). "A Botanist's random impressions of Jamaica". Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London. 170 (2): 134–147. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1959.tb00839.x.

- Stearn, William T. (December 1958). "Botanical exploration to the time of Linnaeus". Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London. 169 (3): 173–196. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1958.tb01472.x.

- Stearn, W. T. (January 1959a). "The Background of Linnaeus's Contributions to the Nomenclature and Methods of Systematic Biology". Systematic Zoology. 8 (1): 4–22. doi:10.2307/2411603. JSTOR 2411603.

- Stearn, W. T. (December 1960). "Mrs. Agnes Arber: Botanist and Philosopher, 1879–1960". Taxon (Reprint of obituary in The Times 24 March 1960). 9 (9): 261–263. doi:10.1002/j.1996-8175.1960.tb02799.x. JSTOR 1217828.

- Stearn, William T. (1960a). "Franz Bauer and Ferdinand Bauer, masters of botanical illustration". Endeavour. First Series. 19: 27–35.

- Stearn, William T. (1 January 1962). "The Influence of Leyden on Botany in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries". The British Journal for the History of Science. 1 (2): 137–158. doi:10.1017/s0007087400001321. JSTOR 4025129. S2CID 145329825.

- Stearn, William T. (1965). "The Origin and Later Development of Cultivated Plants". Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society. 90: 279–291, 322–341.

- Stearn, William (15 October 1965a). "The five brethren of the rose: An old botanical riddle" (PDF). Huntia. 2: 180–184.

- Stearn, William T. (1 January 1967). "Sibthorp, Smith, the 'Flora Graeca' and the 'Florae Graecae Prodromus'". Taxon. 16 (3): 168–178. doi:10.2307/1216982. JSTOR 1216982.

- Stearn, William T. (1969). "The Jamaican species of Columnea and Alloplectus (Gesneriaceae)". Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History), Botany. 4 (5): 179–236.

- Stearn, William T. (December 1976). "From Theophrastus and Dioscorides to Sibthorp and Smith: the background and origin of the Flora Graeca". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 8 (4): 285–298. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1976.tb00251.x. PMID 11631653.

- Stearn, William (August 1977). "The Earliest European Acquaintance with Tropical Vegetation". Gardens' Bulletin, Singapore. 29: 13–18.

- Stearn, W. T. (1978). "European species of Allium and allied genera of Alliaceae; a synonymic enumeration". Annales Musei Goulandris. 4: 83–198.

- Stearn, W. T. (1981a). "The genus Allium in the Balkan Peninsula". Botanische Jahrbücher. 102: 201–203.

- Stearn, William T. (1986). "Historical Survey of the Naming of Cultivated Plants". Acta Horticulturae. 182 (182): 18–28. doi:10.17660/ActaHortic.1986.182.1.

- Stearn, William T. (1 May 1986a). "The Wilkins Lecture, 1985: John Wilkins, John Ray and Carl Linnaeus". Notes and Records of the Royal Society. 40 (2): 101–123. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1986.0007. ISSN 0035-9149. S2CID 145353174.

- Stearn, William T. (1989a). "List of publications of John S. L. Gilmour". Plant Systematics and Evolution. 167 (1–2): 109–112. doi:10.1007/BF00936553. S2CID 677643.

- Stearn, W. T. (October 2007) [1986]. "Society for the Bibliography of Natural History, later the Society for the History of Natural History, 1936–1985. A quinquagenary record". Archives of Natural History. 34 (2): 379–396 (sup. 1–15). doi:10.3366/anh.2007.34.2.379.

Books

- Stearn, William T. (2002) [Cassell: 1972]. Stearn's dictionary of plant names for gardeners: a handbook on the origin and meaning of the botanical names of some cultivated plants. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. ISBN 978-0-88192-556-2.

- Stearn, William T. (1990). Flower artists of Kew: botanical paintings by contemporary artists. London: Herbert Press in association with the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. ISBN 978-1-871569-16-2.

Chapters

- Stearn, W. T. A bibliography of the books and contributions to periodicals written by Reginald Farrer, with obituaries etc. pp. 99–113., in Cox (1930)

- Stearn, W. T. Botanical gardens and botanical literature in the eighteenth century. pp. xli–cxl., in Hunt et al. (1958–1961) vol. 2

- Stearn, W. T. Berberidaceae. pp. 244–245., in Tutin et al. (1964–1980) vol. 1

- Stearn, W. T. Vinca. Lycium. pp. 69, 193–194., in Tutin et al. (1964–1980) vol. 3

- Stearn, W. T. The principles of botanical nomenclature, their basis and history. pp. 86–101., in Green (1973)

- Stearn, W. T. (1980). Allium. Nectaroscordum. Nothoscordum. pp. 49–70. ISBN 978-0-521-20108-7., in Tutin et al. (1964–1980) vol. 5

- Stearn, W. T. (1989). Nandina, Ranzania, Epimedium, Vancouveria, Jeffersonia, Caulophyllum, Gymnospermium, Bongardia, Diphylleia, Podophyllum (Berberidaceae). pp. 370–371, 389–396. ISBN 978-0-521-76151-2., in Cullen et al. (2011) vol. 3 (vol. 2: pp. 390, 410ff in 2nd. ed.)[lower-alpha 2]

- Stearn, W. T. Alliaceae; Amaryllidaceae. pp. 75–87., in Noltie (1994)

- Stearn, W. T. (1995). Paeonia. pp. 17–23. ISBN 978-0-521-76151-2., in Cullen et al. (2011) vol. 4 (vol. 2: pp. 444ff in 2nd. ed.)

- Stearn, W. T. The life, times and achievements of John Lindley, 1799–1865. pp. 15–72., in Stearn (1999)

Collaborative and edited work

Books and articles

- Baumann, Hellmut (1993) [1986]. Die griechische Pflanzenwelt in Mythos, Kunst und Literatur [The Greek Plant World in Myth, Art, and Literature]. trans. William Thomas Stearn, Eldwyth Ruth Stearn. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. ISBN 9780881922318.

- Blatter, Ethelbert; Millard, Walter Samuel (1954) [1937]. Some Beautiful Indian Trees (2nd ed.). Bombay Natural History Society. ISBN 978-0-19-562162-4.

- Blunt, Wilfred; Stearn, William (1973). Captain Cook's Florilegium: A Selection of Engravings from the Drawings of Plants Collected by Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander on Captain Cook's First Voyage to the Islands of the Pacific. London: Lion and Unicorn Press. ISBN 978-0-902490-12-3. (see Banks' Florilegium)

- Blunt, Wilfrid (2001). Linnaeus: the complete naturalist. Introduction by William T. Stearn. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-09636-0.

- Bowles, E. A.; Stearn, W. T. (1947). "The History of Anemone japonica". Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society. 72: 261–268, 297–308.

- Desmond, Ray (1994) [1977]. Dictionary of British and Irish botanists and horticulturists: including plant collectors, flower painters and garden designers (2nd ed.). London: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-85066-843-8.

- Gage, Andrew Thomas; Stearn, William Thomas (1988) [1938]. A bicentenary history of the Linnean Society of London (Revised ed.). London: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-273150-1.

- Gilmour, John; Stearn, W. T. (1932). "Schedae ad Herbarium Florae Cantabrigiensis. Decades I—II Schedae ad Sertum Cantabrigiense Exsiccatum Decades I—II" (PDF). Journal of Botany. 70 sup.: 1–29.

- Goodwin, G. H.; Stearn, W. T.; Townsend, A. C. (January 1962). "A catalogue of papers concerning the dates of publication of natural history books. Fourth supplement". Journal of the Society for the Bibliography of Natural History. 4 (1): 1–19. doi:10.3366/jsbnh.1962.4.1.1.

- Goulimis, Constantine; Stearn, William T. (1968). Wild Flowers of Greece. Illustrated by Niki Goulandris. Athens: Goulandris Natural History Museum.

- Hara, Hiroshi; Stearn, William Thomas; Williams, L. H. J. (1978–1982). An enumeration of the flowering plants of Nepal. 3 vols. London: Trustees of British Museum. ISBN 978-0-565-00777-5.

- Linnaeus, Carl (1753). Stearn, William T. (ed.). Species plantarum 2 vols (Facsimile 1957–1959 ed.). London: Ray Society. (see Species plantarum)

- Linnaeus, Carl (1754). "Notes on Linnaeus's Genera plantarum, pp. v–xxiv". In Stearn, William T. (ed.). Genera plantarum. Historiae naturalis classica (5th Facsimile 1960 ed.). Weinheim: J. Cramer. (see Genera plantarum)

- Linnaeus, Carl (1767–1771). "Introductory notes, pp. v–xxiv". In Stearn, William T. (ed.). Mantissa plantarum. Historiae naturalis classica (Facsimile 1961 ed.). Weinheim: J. Cramer. (see Mantissa plantarum)

- Raven, J. E. (1990). "Plants and plant lore in ancient Greece, with an introduction by William T. Stearn". Annales Musei Goulandris. 8: 129–180.

- Raven, J.E. (2000). Stearn, W.T. (ed.). Plants and plant lore in ancient Greece. Oxford: Leopard's Press. ISBN 978-0-904920-40-6.

- Sitwell, Sacheverell (1990) [1956 London: Collins]. Synge, Patrick Millington (ed.). Great flower books, 1700–1900: a bibliographical record of two centuries of finely-illustrated flower books (New ed.). London: Witherby. ISBN 978-0-85493-202-3.[lower-alpha 3]

- Stearn, W. T., ed. (1953). International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants formulated and adopted by the International Botanical Congress Committee for the Nomenclature of Cultivated Plants and the International Committee on Horticultural Nomenclature and Registration at the Thirteenth International Horticultural Congress, London, September 1952. London: Royal Horticultural Society.

- Stearn, William T., ed. (1973a). "Ray, Dillenius, Linnaeus and the Synopsis methodica Stirpium Britannicarum". John Ray, Synopsis Methodica Stirpum Britannicarum. Third edition 1724. Carl Linnaeus, Flora Anglica. 1754 & 1759. Ray Society. pp. 1–90. ISBN 978-0-903874-00-7.

- Stearn, William T. (1976). The Australian flower paintings of Ferdinand Bauer. Introduction by Wilfrid Blunt. London: Basilisk Press. ISBN 978-0-905013-01-5. (see Ferdinand Bauer)

- Green, P. S. (1977). "A Selection of Australian Flower Paintings by Ferdinand Bauer" (PDF). Journal of the Adelaide Botanic Garden (Review). 1 (2): 145–149.

- Stearn, William T.; Bridson, Gavin (1978). Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778): a bicentenary guide to the career and achievements of Linnaeus and the collections of the Linnean society. London: Linnean Society. ISBN 978-0-9506207-0-1.

- Stearn, W. T.; Davis, P. H. (1984). Peonies of Greece: A Taxonomic and Historical Survey of the Genus Paeonia in Greece. Athens: Goulandris Natural History Museum. ISBN 978-0-565-00975-5.

- Stearn, W. T. Biographical and bibliographical introduction to John Raven's lectures on Greek plants. pp. 130–138., in Raven (1990)

- Stearn, William T.; Brickell, Christopher (1987). An English florilegium: flowers, trees, shrubs, fruits, herbs, the Tradescant legacy. Watercolour paintings by Mary Grierson. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-23486-0.

- Stearn, William T.; Roach, Frederick A. (1989). Hooker's finest fruits: a selection of paintings of fruits by William Hooker (1779–1832). New York City: Prentice Hall Press. ISBN 978-0-13-394545-4. (see William Hooker)

- Stewart, Joyce; Stearn, William T. (1993). The orchid paintings of Franz Bauer. London: Herbert, in association with the Natural History Museum. ISBN 978-1-871569-58-2.

- Woodcock, Hubert Bayley Drysdale; Stearn, William Thomas (1950). Lilies of the World: Their Cultivation & Classification. Country Life.

Chapters

- Stearn, W. T.; Campbell, E. (2011). Allium. pp. 231–246. ISBN 978-0-521-76147-5., in Cullen et al. (2011) vol. 2 (vol. 1: pp. 133–146 in 2nd. ed.)

- Stearn, W. T.; Landström, T. Ornithogalum. pp. 686–694., in Strid & Tan (1991)

Websites

- BSA (2017). "Botanical Society of America". Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- BSBI (April 2016). "Botanical Society of Britain & Ireland". Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- "Cambridge 2000". 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2017.