Waldorf Astoria New York

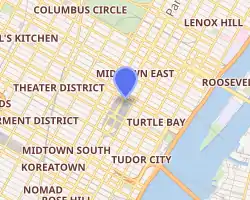

The Waldorf Astoria New York is a luxury hotel in Midtown Manhattan in New York City. The structure, at 301 Park Avenue between 49th and 50th Streets, is a 47-story 625 ft (191 m) Art Deco landmark designed by architects Schultze and Weaver, which was completed in 1931. The building was the world's tallest hotel from 1931 until 1963 when it was surpassed by Moscow's Hotel Ukraina by 23 feet (7.0 m). An icon of glamour and luxury,[5] the current Waldorf Astoria is one of the world's most prestigious and best-known hotels.[6] Waldorf Astoria Hotels & Resorts is a division of Hilton Hotels, and a portfolio of high-end properties around the world now operates under the name, including in New York City. Both the exterior and the interior of the Waldorf Astoria are designated by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission as official landmarks.

| Waldorf Astoria New York | |

|---|---|

| |

The hotel from the north, with St. Bart's visible in the foreground. | |

| |

| Hotel chain | Waldorf Astoria |

| General information | |

| Location | 301 Park Avenue Manhattan, New York City |

| Coordinates | 40°45′23″N 73°58′27″W |

| Opened | 1931 |

| Closed | 2017 (temporarily for renovations) |

| Owner | Dajia Insurance Group Co. |

| Management | Hilton Worldwide |

| Height | 625 ft (191 m) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 47 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Schultze & Weaver |

| Other information | |

| Number of rooms | 1,413[1] |

| Number of restaurants | Peacock Alley Bull and Bear Steakhouse La Chine |

| Website | |

| Official hotel website | |

| [2][3][4] | |

The original Waldorf–Astoria was built in two stages along Fifth Avenue and opened in 1893; it was demolished in 1929 to make way for the construction of the Empire State Building. Particularly after its relocation, the Waldorf Astoria gained international renown for its lavish dinner parties and galas, often at the center of political and business conferences and fundraising schemes involving the rich and famous. After World War II, it played a significant role in world politics and the Cold War, culminating in the controversial World Peace Conference of March 1949. Conrad Hilton acquired management rights to the hotel on October 12, 1949, and the Hilton Hotels Corporation finally bought the hotel outright in 1972. It underwent a $150 million renovation ($493 million in 2021 dollars [7]) by Lee Jablin in the 1980s and early 1990s. The Anbang Insurance Group of China (later absorbed into Dajia Insurance Group) purchased the Waldorf Astoria New York for US$1.95 billion in 2014, making it the most expensive hotel ever sold. The Waldorf was closed in 2017 and its upper-floor hotel rooms were converted into 375 condominiums called The Towers of the Waldorf Astoria. The renovated structure will retain 375 hotel rooms on the lowest 18 floors.

The Waldorf Astoria and Towers has a total of 1,413 hotel rooms as of 2014. In 2009, when it had 1,416 rooms, the main hotel had 1,235 single and double rooms and 208 mini-suites, while the Waldorf Towers, from the 28th floor up to the 42nd, had 181 rooms, of which 115 were suites, with one to four bedrooms. Several of the luxury suites are named after celebrities who lived or stayed in them such as the Cole Porter Suite, the Royal Suite, named after the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, the MacArthur Suite, and the Churchill Suite. The most expensive room, the Presidential Suite, is designed with Georgian-style furniture to emulate that of the White House. It was the residence of Herbert Hoover from his retirement for over 30 years, and Frank Sinatra kept a suite at the Waldorf from 1979 until 1988. The hotel has three main restaurants: Peacock Alley, The Bull, and Bear Steak House, and La Chine—a new Chinese restaurant that replaced Oscar's Brasserie in late 2015. Sir Harry's Bar, also located in the hotel, is named after British explorer Sir Harry Johnston.

Name

The name of the hotel is ultimately derived from the town of Walldorf, which lies in south-west Germany, close to Mannheim and Heidelberg. Walldorf is the ancestral home of the prominent German-American Astor family who originated there.[8] In German, "Waldorf" (with one l, like the hotel) means "Whale Village" (Wal = whale, Dorf = village), and "Walldorf" (with two l's, like the town) means "Rampart Village" (Wall = rampart). The name of the town, however, formed through an elision: "Walddorf" (with two d's), meaning "Forest Village" (Wald = forest), became "Walldorf". An oak tree in the coat of arms of the town refers to this etymology.

The hotel was originally known as the Waldorf-Astoria with a single hyphen, as recalled by a popular expression and song, "Meet Me at the Hyphen". The sign was changed to a double hyphen, looking similar to an equals sign, by Conrad Hilton when he purchased the hotel in 1949.[9] The double hyphen visually represents "Peacock Alley", the hallway between the two hotels that once stood where the Empire State building now stands today.[10] The use of the double hyphen was discontinued by its parent company Hilton in 2009, shortly after the introduction of the Waldorf Astoria Hotels and Resorts chain.[11] The hotel has since been known as the Waldorf Astoria New York, without any hyphen, though this is sometimes shortened to the Waldorf Astoria.

History

Original buildings

Creation

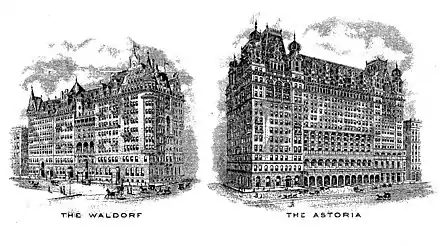

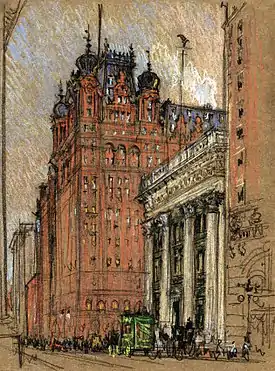

The original hotel started as two hotels on Fifth Avenue built by feuding relatives. The first hotel, the 13-story, 450-room Waldorf Hotel, designed by Henry Janeway Hardenbergh in the German Renaissance style,[12] was opened on March 13, 1893, at the corner of Fifth Avenue and 33rd Street, on the site where millionaire developer William Waldorf Astor had his mansion.[13][14] The original hotel stood 225 feet (69 m) high, with a frontage of about 100 feet (30 m) on Fifth Avenue, with an area of 69,475 square feet (6,454.4 m2).[15] The original hotel was described as having a "lofty stone and brick exterior", which was "animated by an effusion of balconies, alcoves, arcades, and loggias beneath a tile roof bedecked with gables and turrets".[16] William Astor, motivated in part by a dispute with his aunt Caroline Webster Schermerhorn Astor, had built the Waldorf Hotel next door to her house, on the site of his father's mansion. The hotel was built to the specifications of founding proprietor George Boldt, who owned and operated the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel, a fashionable hotel on Broad Street in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, with his wife Louise. Boldt was described as "Mild-mannered, undignified, unassuming", resembling "a typical German professor with his close-cropped beard which he kept fastidiously trimmed... and his pince-nez glasses on a black silk cord".[17] Boldt continued to own the Bellevue even after his relationship with the Astors blossomed.

At first, the Waldorf appeared destined for failure. It was "Astor's Folly",[18] with the general perception of the palatial hotel being that it had no place in New York City.[19] Wealthy New Yorkers were angry because they viewed the construction of the hotel as the ruination of a good neighborhood. Business travelers found it too expensive and too far uptown for their needs. In the face of all of this, George Boldt decided that the hotel would host a benefit concert for St. Mary's Hospital for Children on its opening day. The hospital was the favorite charity of those on the Social Register. The ballroom filled with many of New York's First Families, who had paid five dollars for the concert and dinner at the Waldorf.[20] It soon became a major success, earning $4.5 million in its first year, exorbitant for that period.[17]

William Astor's construction of a hotel next to his aunt's house worsened his feud with her, but with Boldt's assistance, Waldorf's cousin, John Jacob Astor IV, persuaded his mother to move uptown. On November 1, 1897, John Jacob Astor IV opened the 17-story Astoria Hotel on an adjacent site, and leased it to Boldt.[14] The hotels were initially built as two separate structures, but Boldt planned the Astoria so it could be connected to the Waldorf by an alley. Peacock Alley was constructed to connect them; it was named so by New Yorkers for the parade of well-dressed, well-to-do people who strutted between the two fashionable buildings.[21] The hotel subsequently became known as the "Waldorf-Astoria", the largest hotel in the world at the time.[22][23]

Heyday

With a telephone in every room and first-class room service, the hotel was designed specifically to cater to the needs of the socially prominent "wealthy upper crust" of New York and distinguished foreign visitors to the city. [6][24] The hotel became, according to author Sean Dennis Cashman, "a successful symbol of the opulence and achievement of the Astor family".[25] It was the first hotel to offer complete electricity and private bathrooms.[26] Founding proprietor Boldt, whose motto was "the guest is always right",[27] became wealthy and prominent internationally, if not so much a popular celebrity as his famous employee, Oscar Tschirky, known as "Oscar of the Waldorf", maître d'hôtel from the hotel's inauguration in 1893 until his retirement in 1943. Tschirky had arrived in the United States from Switzerland 10 years prior to applying for the position at the new Waldorf, and over the years grew to possess a great knowledge of cuisine.[28] He authored The Cookbook by Oscar of the Waldorf (1896), a 900-page book featuring all of the popular recipes of the day, including his own, for which he garnered great acclaim, such as Waldorf salad, eggs Benedict, and Thousand Island dressing, which remain popular worldwide today. James Remington McCarthy wrote in his book Peacock Alley that Oscar gained renown among the general public as an artist who "composed sonatas in soups, symphonies in salads, minuets in sauces, lyrics in entrees".[28] In 1902, Tschirky published Serving a Course Dinner by Oscar of the Waldorf-Astoria, a booklet that explains the intricacies of being a caterer to the American and international elite.[28] Tschirky had an excellent memory and an encyclopedic memory of the culinary preferences of many of the guests, which further added to his popularity. In 1937, for instance, he recalled the opening night and notable people present at the old Waldorf, a guest at the old building known to the public as Buffalo Bill, and spoke at length about the planning for the Panama Canal that took place at the Waldorf-Astoria.[29][30]

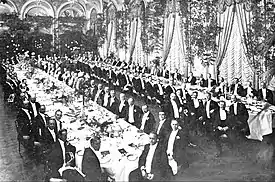

The Waldorf gained significant renown internationally for its fundraising dinners and balls, regularly attracting notables of the day such as Andrew Carnegie, who became a fixture.[31] Banquets were often held in the ballroom for esteemed figures and international royalty. The Waldorf Astoria was influential in advancing the status of women, who were admitted singly without escorts. George Boldt's wife, Louise Kehrer Boldt, was influential in evolving the idea of the grand urban hotel as a social center, particularly in making it appealing to women as a venue for social events. On February 11, 1899, Oscar hosted a lavish dinner reception that the New York Herald Tribune cited as the city's costliest dinner at the time. Some $250 was spent per guest, with bluepoint oysters, green turtle soup, lobster, ruddy duck, and blue raspberries.[32] One article that year claimed that at any one time, the hotel had $7 million worth of valuables locked in the safe, testament to the wealth of its guests.[33] In 1902, a lavish dinner was organized for Prince Henry of Prussia, and in 1909, banquets attended by hundreds were organized for Arctic explorer Frederick Cook in September and Elbert Henry Gary, a founder of US Steel, the following month.[34][35]

The United States Senate inquiry into the sinking of the RMS Titanic was opened at the hotel on April 19, 1912, and continued there for some time in the Myrtle Room,[36] before moving on to Washington, D.C.[37] John Jacob Astor IV was one of the people who perished on its ill-fated journey. Seven senators were present on the subcommittee, including William Alden Smith (Republican, Michigan) as chair, Jonathan Bourne (R, Oregon), Theodore E. Burton (R, Ohio), Duncan U. Fletcher (Democrat, Florida), Francis G. Newlands (D, Nevada), George Clement Perkins (R, California), and Furnifold McLendel Simmons (D, North Carolina).[38] The composition of the subcommittee was carefully chosen to represent the conservative, moderate, and liberal wings of the two parties.[39]

In 1919, restaurateur Louis Sherry announced an "alliance" with the Waldorf-Astoria that involved both his candies and catering services.[40] Although it was not disclosed at that time, at some point, ownership of Louis Sherry Inc. was significantly vested in "Boomer-duPont interests", a reference to Lucius M. Boomer, then chairman of the Waldorf-Astoria, and T. Coleman du Pont. Upon his death that year, William Waldorf Astor was reputed to have been worth £200 million, which he left in trust for his two sons Waldorf and John Jacob. His half share of the Waldorf Astoria and the Astor Hotel at the time were reported to have been worth £10 million.[41] On the evening of November 15, 1926, the National Broadcasting Company broadcast its inaugural program from the grand ballroom of the old Waldorf-Astoria. Among the entertainers heard by radio listeners was Will Rogers.[42] The network became the Red Network on January 1, 1927, when NBC launched its second network, designated the Blue Network.[43] An antitrust suit forced the sale of the Blue Network in 1942; it became the American Broadcasting Company.[44]

The hotel faced stiff competition from the early 20th century, with a range of new hotels springing up in New York City such the Hotel Astor (1904), St. Regis (1904), the Knickerbocker (1906), and the Savoy-Plaza Hotel (1927).[45] By the 1920s, the hotel was becoming dated, and the elegant social life of New York had moved much farther north than 34th Street. The Astor family finally sold the hotel to the developers of the Empire State Building and closed the hotel on May 3, 1929. It was demolished soon after.[14]

Early years and international politics

The idea of a new Waldorf-Astoria hotel was based on the concept that a large, opulent hotel should be available in New York for distinguished visitors. Financial backing was not difficult to get in the summer of 1929, as times were prosperous; the stock market had not yet crashed nor had the Depression arrived. However, before ground was broken for the new building, some of the investors became dubious about whether this was the right time to be investing in a luxury hotel.[46][47] The land for the new hotel was formerly owned by the New York Central Railroad, which had operated a power plant for Grand Central Terminal on the site.[48] New York Central had promised $10 million toward the building of the new Waldorf-Astoria. The railroad and all the other investors decided to honor their commitments and take their chances with the uncertain financial climate.[46][47]

The new building opened on Park Avenue, between East 49th and East 50th streets, on October 1, 1931. It was the tallest and largest hotel in the world at the time,[49] covering the entire block. The slender central tower became known as the Waldorf Towers, with its own private entrance on 50th Street, and consisted of 100 suites, about one-third of which were leased as private residences.[50] President Herbert Hoover said on the radio, broadcast from the White House: "The opening of the new Waldorf Astoria is an event in the advancement of hotels, even in New York City. It carries great tradition in national hospitality...marks the measure of nation's growth in power, in comfort and in artistry...an exhibition of courage and confidence to the whole nation".[14] About 2,000 people were in the ballroom listening to this speech, but by the end of the business day, the 2,200-room hotel had only 500 occupancies. The Waldorf-Astoria did not begin operating at a profit until 1939.[47] Lucius Boomer continued to manage the hotel in the 1930s and 1940s, a commanding figure to whom Tony Rey referred as "the greatest hotelman of his era".[51] Boomer was elected chairman of the board of the Waldorf-Astoria Corporation on February 20, 1945, a position he held until his death in July 1947.[52][53]

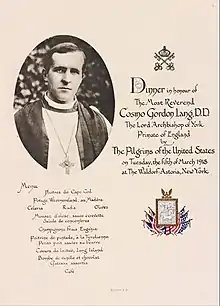

Like the original hotel, from its inception, the Waldorf Astoria gained worldwide renown for its glamorous dinner parties and galas, often at the center of political and business conferences and fundraising schemes. Author Ward Morehouse III has referred to the Waldorf Astoria as "comparable to great national institutions" and a "living symbol deep within our collective consciousness".[54] It had the "greatest banquet department in the world" at the time according to restaurateur Tom Margittai, with the center of activity being the Grand Ballroom.[55] On August 3, 1932, some 200 people representing the "cream of New York's literary world" attended the Waldorf Astoria to honor Pearl S. Buck, the author of The Good Earth, which was the best-selling novel in the United States in 1931 and 1932.[56] One dinner alone, a relatively "small dinner" attended by some 50 people in June 1946, raised over $250,000.[57] During the 1930s and 1940s the hotel's guests were also entertained at the elegant "Starlight Roof" nightclub by the Waldorf-Astoria Orchestra and such noted musicians as: Xavier Cugat, Eddie Duchin, Lester Lanin and Glenn Miller.[58][59][60]

The hotel played a considerable role in the emerging Cold War and international relations during the postwar years, staging numerous events and conferences. On March 15, 1946, Winston Churchill attended a welcoming dinner at the hotel given by Governor Thomas E. Dewey, 10 days after making his famous Iron Curtain speech,[61] and from November 4 to December 12, 1946, the Big Four Conference was held in Jørgine Boomer's apartment on the 37th floor of the Towers between the United States, Britain, France, and the Soviet Union to discuss the future of Eastern Europe.[62] On November 24, 1947, 48 prominent figures of the Hollywood film industry, including various film executives such as Louis B. Mayer of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Harry Cohn of Columbia Pictures, Spyros Skouras of 20th Century Fox, Albert Warner of Warner Bros., and Eric Johnston, the head of the Association of Motion Picture Producers, met at the Waldorf Astoria and discussed what would become the Waldorf Statement, banning people with Communist beliefs or tendencies from the Hollywood film industry.[63] The statement was a response to the contempt of Congress charges against the so-called "Hollywood Ten".

From March 27 to 29, 1949, the Cultural and Scientific Conference for World Peace, also known as the Waldorf World Peace Conference, was held at the hotel to discuss the emerging Cold War and the growing divide between the US and the Soviet Union. The conference came at a time when deep anti-Communist sentiment and suspicion of the Soviet Union existed in the United States, following the Berlin Blockade and the Czechoslovak coup d'état the previous year.[64] The event was organized by the struggling American Communist Party. It was sponsored by many individuals who were not Stalinists, such as Leonard Bernstein, Marlon Brando, Albert Einstein, and Aaron Copland. They joined with the intention of promoting peace, and the Party found them useful.[65] The conference was attended by the likes of Soviet Foreign Minister Andrey Vyshinsky, composer and pianist Dmitri Shostakovich, and writer Alexsander Fadeyev. Tension mounted during the controversial event, and culminated when Shostakovich, in front of a crowd of some 800 people, launched a scathing attack on western civilization, announcing, "a small clique of hatemongers was preparing world public opinion for the transition from the cold war to outright aggression".[66] The event was picketed in a counterattack by anti-Stalinists running under the banner of America for Intellectual Freedom, and prominent individuals such as Irving Howe, Dwight Macdonald, Mary McCarthy, Robert Lowell, and Norman Mailer angrily denounced Stalinism at the hotel.[65]

On June 21, 1948, a press conference at the hotel introduced the LP record.[67]

In 1954, Israeli statesman and archaeologist Yigael Yadin met secretly with the Syriac Orthodox Archbishop Mar Samuel in the basement of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel to negotiate the purchase of four Dead Sea Scrolls for Israel. The scrolls were kept in a vault at the Waldorf-Astoria branch of New York's Chemical Bank. At the request of the Israeli government, respected biblical scholar Dr. Harry Orlinsky examined the scrolls and verified their authenticity; Yadin paid $250,000 for all four.[68][69][lower-alpha 1]

Restaurateur George Lang began working at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in 1955, and on December 13, 1955, he helped organize the American Theatre Wing's First Night Ball to celebrate Helen Hayes's 50th year in show business.[71] He did much to organize dinners at the Waldorf to assist Hungarian issues and relief. On one occasion, an event was attended by Edward G. Robinson and pianist Doklady and some $60,000 were raised.[72]

April in Paris Ball

The April in Paris Ball was an annual gala event whose mission was to improve Franco-American relations, to share cultures, and to help assist the US and French charities, aside from commemorating the 2000th anniversary of the founding of Paris.[73] It was established by Claude Philippe, the hotel banquet manager, in 1952. While the hotel's management handled invitations and publicity, other details were coordinated by socialites.[74] Elsa Maxwell was given the primary responsibility in organizing it.[75] It was initially held annually in April, but according to Ann Vaccaro, former executive director of the ball, it was changed to October because "Mr. Philippe decided that because there are so many balls in the spring, he would make it in October".[76] After being changed to October, it often marked the start of the US fall social season. It was staged in the Grand Ballroom at the Waldorf for eight years before moving to the Hotel Astor in 1960, the Seventh Regiment Armory in 1961, and other venues.[77]

The ball was designed to cater to "very, very high-class people" according to Vaccaro.[78] Raffle tickets cost US$100 per person and offered opulent prizes such as a US$5000 bracelet and other jewels, expensive furs, perfumes, and even cars.[78] In the 1960 event, prizes given included a Ford Thunderbird car, a chinchilla coat, a Renault Dauphine, a TV Hi-Fi system, an electric typewriter, 25 cases of expensive French wines, original paintings and porcelains, jewels, clocks, evening bags, and a pedigreed poodle; guests were given gift boxes containing gold key rings and jewelry, champagne and brandy, Maxim ashtrays, pipes, silver bottle openers, hats and scarves, and flowers.[77] Every guest was said to have gone home with at least one gift in return. In the 1979 event, some US$106,000 worth of prizes were given out.[78] Over its history, the ball, which was exempt from taxes, earned millions of dollars, which went primarily to over 20 American charities such as the American Cancer Society, with 15 to 20% going towards French charities. A staff of three people was paid full-time throughout the year to organize it. Of the expenses of the ball, founder Philippe stated, "We charge the most, give the most, and make the most – it's a success formula".[73] Bernard F. Gimbel served as chief treasurer.[78]

The Paris Ball became a notable event in the annual calendar during the 1950s, with one early show featuring a "three-hour spectacular of five tableaux, directed by Stuart Chaney", [depicting] a 12th-century scene of troubadours at the court of Eleanor of Aquitane, Henry VIII's meeting at the Field of the Cloth of Gold, Louis XIV at Versailles, and a fashion show of 40 creations by Dior, Fath, Balmain, Desses, and Givenchy".[73] French stars Juliette Gréco, Jean Sablon, Beatrice Lillie, John Loder and many others were flown over for the ball. The 1957 event was attended by some 1300 guests, including the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, Senator John F. Kennedy, his wife, Jackie, and Marilyn Monroe, who paid $100 each and donated $130,000 to charities.[79][80] The following year, the ballroom was decorated with 30 feet (9.1 m) high chestnut trees, earning US$170,000 for charities.[81] The final ball to be hosted in the hotel was held on April 10, 1959, with the main theme being the Parisian circus of the 18th century. Genuine circus costumes from the period were flown over from France, and the ball was attended by Marlene Dietrich, who performed two Maurice Chevalier songs, wearing a top hat, trousers, a waistcoat, and white gloves.[82]

Later history

On May 6, 1963, Time celebrated its 40th anniversary at the hotel. The event was attended by some 1500 celebrities,[83] including General Douglas MacArthur, Jean Monnet, Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., Bob Hope, Joe Louis, David O. Selznick, Secretary of State Dean Rusk, Edward Kennedy, Henry Ford II, and many others.[84] On October 4, 1965, Pope Paul VI made the first papal visit to the United States. He met with President Lyndon B. Johnson at the Waldorf Astoria.[85] In 1968, British rock band The Who checked into the hotel, where they encountered difficulties with the staff of the Waldorf Astoria. Due to the band's reputation for trashing their hotel rooms and rowdy behavior, the Waldorf demanded that they pay cash upfront. However, following their gig, the band members were refused access to their hotel rooms, where their luggage was being kept. Tony Fletcher, in his biography on Keith Moon, claims that Moon challenged the staff and blew the door to their room off the hinges with his cherry bombs and retrieved their luggage, which prompted The Who to be shown the door and banned from the hotel for life.[86] However, clearly the ban was later revoked as they performed at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Induction at the Waldorf on January 17, 1990.[87]

.jpg.webp)

Soon after the opening of the hotel in 1931, hotelier Conrad Hilton, almost bankrupt at the time, reportedly cut out a photograph of the hotel from a magazine and wrote across it, "The Greatest of Them All".[88] He acquired management rights to the hotel on October 12, 1949.[89][90] The Hilton Hotels Corporation finally bought the hotel outright in 1972.[91]

In the 1970s, the Waldorf Astoria continued to play an important role in international politics, particularly between the US and the Middle East. In November 1974, a "20-car motorcade, with eight shotgun-toting police marksmen aboard in bullet-proof vests" brought Palestinian Fatah party leader Farouk Kaddoumi to the Waldorf from John F. Kennedy International Airport.[92] The Waldorf was on red alert, and German Shepherd sniffer dogs were brought in prior to his arrival to look for possible bombs. Fifteen suites of the hotel were reserved for the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) delegation. The following month, President Ford met with Nelson Rockefeller after he was voted Vice President, and a 90-minute press conference was held in a suite in the hotel.[93] In November 1975, the US government insisted that PLO leader Yasser Arafat stay at the Waldorf during his visit to America, against the wishes of the hotel staff; security was stepped up severely.[94] On August 12, 1981, IBM unveiled its Personal Computer in a press conference at the Waldorf Astoria,[95][96] and in 1985, the NBA held its first-ever draft lottery between nonplayoff teams at the Starlight Room. The lottery was for the 1985 NBA Draft in which Patrick Ewing was the consensus number-one pick.[97]

Lee Jablin, of Harman Jablin Architects, fully renovated and upgraded the historical property to its original grandeur during the mid-1980s through the mid-1990s in a $150 million renovation.[98] The hotel was named an official New York City Landmark in 1993.[14] On May 27, 2001, the Eastern Diocese of the Armenian Church of America had a grand banquet at the hotel to celebrate the 1700th anniversary of Armenia's conversion to Christianity, with Ambassador Edward Djerejian as guest speaker.[99] On May 7, 2004, a press conference was held by MGM, discussing Steve Martin's The Pink Panther of the Pink Panther series. The 5th Annual DGA Honors Gala was held at the Waldorf on September 29.[100]

In 2006, Hilton launched Waldorf Astoria Hotels & Resorts, a brand named for the hotel. Branches of the Waldorf Astoria are now located in Arizona, California, Florida, Hawaii, and Louisiana in the United States, and abroad in France, Israel, Italy, and Saudi Arabia.[101] In 2006, Hilton was reported to be considering opening a new Waldorf Astoria hotel on the Las Vegas Strip.[102] In 2008, the Waldorf Astoria opened the Guerlain and Spa Chakra, Inc. spa at the hotel, as part of the Waldorf Astoria Collection, which offers a "body massage and facial using Guerlain's age-defying Orchidee Imperiale skincare".[103] The Waldorf Astoria New York is a member of Historic Hotels of America, the official program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. "The Towers of the Waldorf Astoria" continues to operate as a boutique "hotel within a hotel".[14]

In October 2014, Chinese company Anbang Insurance Group was announced to have purchased the Waldorf Astoria New York for US$1.95 billion, making it the most expensive hotel ever sold.[1][104] On July 1, 2016, Anbang announced plans to refurbish the hotel and turn some rooms into condominiums, The Towers of the Waldorf Astoria. Under the plan, some of the hotel's rooms will be turned into apartments, with the remainder of the rooms remaining hotel suites operated by Hilton.[105][106] The final event in the Grand Ballroom, on February 28, 2017, was a charity gala celebrating NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital with Stevie Wonder playing for the sold-out crowd.[107] As part of the refurbishment process, the hotel closed on March 1, 2017.[108] The hotel's restaurants, including Peacock Alley, The Bull and Bear Steak House, and the recently opened La Chine, closed along with the hotel; they will reopen when the renovation is completed.[109] A week after the hotel closed, on March 7, 2017, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission voted unanimously to list the interiors of the hotel's famous public spaces as New York City landmarks, protecting them from major alterations.[110][111]

In November 2019 it was announced that the 375 condos in the Waldorf-Astoria would go on sale starting in early 2020, while the 375 remaining hotel rooms would not reopen until 2021.[112][113][114][115] The hotel rooms were set to be on the lowest 18 floors.[116] Following Anbang's bankruptcy in 2020, Dajia Insurance Group Co. took over Anbang's American assets, including the Waldorf Astoria.[117] In March 2020, sales started on the 375 condos in the Waldorf-Astoria.[118] By late 2020, the hotel was set to open at the end of 2022;[119][120] however, as of March 2021, the hotel was expected to open in early 2023.[121][122] The renovation of the Waldorf Astoria stalled in mid-2022 as the project exceeded its $2 billion budget.[123][124] According to the Wall Street Journal, this had pushed the renovation back to at least 2024.[124]

Architecture

The hotel was designed by architects Schultze and Weaver and constructed at 301 Park Avenue, just north of Grand Central Terminal. That area was developed atop the existing railroad tracks leading to the station, as part of the Terminal City complex, wherein buildings like the Waldorf Astoria using "air rights" to the space above the tracks.[125] Travel America stated: "To linger in the sumptuous salons of the Waldorf-Astoria is to step back in time. Your trip down memory lane is a flashback to the glamor days of the 1930s when this Art Deco masterpiece was the tallest hotel in the world and the epicenter of elite society. A legendary limestone landmark occupying a whole block of prime real estate in midtown Manhattan, it's still a prestigious address that embodies luxury and power in the richest city on earth."[126]

Form and facade

The 625 ft (191 m) hotel,[127][128] with 47 stories, was the tallest and largest hotel in the world for several years after its completion.[49] The structure uses 1,585 cubic feet (44.9 m3) of black marble imported from Belgium, 600 cubic feet (17 m3) of Brech Montalto and 260 cubic feet (7.4 m3) of Alps Green from Italy, and some 300 antique mantles.[129] In addition, 200 railroad cars brought some 800,000 cubic feet (23,000 m3) of limestone for the building's facing, 27,100 tons of steel for the skeleton superstructure, and 2.595 million square feet (241,100 m2) of terra cotta and gypsum block.[129]

The massing of the hotel rises from a pair of 20-story-high slabs at the base, which run parallel to Park and Lexington Avenues. The slabs contain setbacks at the 18th story on their western elevation and at the 13th and 16th stories on the eastern elevation.[130] The slab on Park Avenue contained a retractable metal and glass roof above the 18th and 19th stories, above the Starlight Roof nightclub.[128] The slabs are covered with gray limestone and lack colorful ornamentation.[131][132] The facade of the lower stories is divided vertically into numerous bays, which contain recessed windows and spandrel panels. There are three patterns of spandrels on the western and eastern elevations of the facade, facing Park and Lexington Avenues respectively.[132] Gilded letters with the hotel's name are placed above the entrances on either avenue.[133][132] On Park Avenue, the letters are flanked by representations of maidens.[134][132]

Above the 20th story, the hotel rises as a single slab to the 42nd story. this slab is oriented parallel to the side streets and is also faced in gray limestone.[132] The 42-story slab is topped by a pair of towers with copper pinnacles.[127][132] The upper stories of the towers are faced in brick, which was intentionally designed to match the stonework on the lower stories.[133][132] The use of brick led many to believe that the builders ran out of money.[129] The Waldorf Astoria's facade has undergone few changes over the years, except for the installation of openings for air conditioners; replacement of aluminum windows; and modifications to storefronts, marquees, and entrances at ground level.[132]

Interior

Such is the architectural and cultural heritage of the hotel that tours are conducted of the hotel for guests.[26] Frommer's has cited the hotel as an "icon of luxury", and highlights the "wide stately corridors, the vintage Deco door fixtures, the white-gloved bellmen, the luxe shopping arcade", the "stunning round mosaic under an immense crystal chandelier", and the "free-standing Waldorf clock, covered with bronze relief figures" in the main lobby. They compare the decor of the rooms to those of an English country house, and describe the corridors as being wide and plush-carpeted, which "seem to go on forever".[5]

Lobby floor

Unlike in other American hotels, the lobby floor of the Waldorf Astoria is raised one story above ground level, which both created the impression of grandeur and allowed storefronts to be placed at ground level. The main lobby, at the center of the lobby floor, measures 82 by 62 feet (25 by 19 m) across and 22 feet (6.7 m) high; it originally had four wood-paneled walls with archways.[135] The lobby is furnished with polished nickel-bronze cornices and rockwood stone. The grand clock, a 4000-lb bronze, was built by the Goldsmith's Company of London originally for the 1893 World Columbia Exposition in Chicago, but was purchased by the Waldorf owners.[136] Its base is octagonal, with eight commemorative plaques of presidents George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant, Andrew Jackson, Benjamin Harrison, and Grover Cleveland, and Queen Victoria and Benjamin Franklin. A shield once belonging to the Waldorf was moved to the Alexis restaurant on W. Franklin Street in 1984.[137] Initially, the north wall of the lobby had a porter and cigar store; the east wall had a transportation desk; and the south wall had a cashier's desk and front-office desk.[135] Special desks in the lobby are allocated to transportation and theatre, where exclusive tickets to many of the city's prominent theaters can be purchased.[26]

In the main foyer is a chandelier measuring 10 feet (3.0 m) by 10 feet (3.0 m).The elevator is furnished with paneled pollard oak and Carpathian elm.[138] The Park Avenue lobby contains classical-style square columns as well as pastoral murals by Louis Rigal.[139][140] The lobby floor contains the room registration and cashier desks, the Empire Room and Hilton Room, the private Marco Polo Club, the Wedding Salon, Kenneth's Salon, the Peacock Alley lounge and restaurant, and Sir Harry's Bar. From 1992 to 2013, Kenneth, sometimes called the world's first celebrity hairdresser,[141] famed for creating Jacqueline Kennedy's bouffant in 1961,[142] moved his hairdressing and beauty salon to the Waldorf after a 1990 fire destroyed his shop on 19 East 54th Street.[143]

The main lobby is surrounded on all four sides by a system of secondary corridors. The eastern corridor allowed direct access from Lexington Avenue to the various rooms on the third and fourth stories.[144] The architects used different colors of marbles for the lobby-floor lounges to distinguish them from each other. The west lounge has French walnut burl panels separated by red French marble; the former north lounge had yellow Siena marble; the south lounge has white gray Breche Montalto marble; and the east arcade has serpentine cladding.[140] Several boutiques surround the lobby, which contains Cole Porter's Steinway & Sons floral print-decorated grand piano on the Cocktail Terrace, which the hotel had once given him as a gift.[145] Porter was a resident at the hotel for 30 years and composed many of his songs here.[146] The Empire Room is where many of the musical and dance performances were put on, from Count Basie, to Victor Borge, Gordon MacRae, Liza Minnelli, George M. Cohan, and Lena Horne, the first black performer at the hotel.[147]

Third and fourth floors

The third floor contains the Grand Ballroom, the Silver Corridor, the Basildon Room, the Jade Room, and the Astor Gallery. Numerous organizations hold their annual dinners in the grand ballroom of the Waldorf, including St. John's University President's Dinner,[148] the Catholic Charities of the Archdiocese of New York's annual gala, during which the Deus Caritas Est Award for philanthropy is presented, and the Alfred E. Smith Memorial Foundation Dinner.[149] The NASCAR Sprint Cup end-of-season awards banquet was held at the Waldorf-Astoria every year between 1981 and 2008 before moving to the Wynn in Las Vegas. It was held initially in the Starlight Room, but from 1985, it was staged in the Grand Ballroom, except in 2001 and 2002.[150] On May 1, 2004, the Waldorf-Astoria was the venue for the Manhattan Hungarian Network Grand Europe Ball, a historic black-tie charitable affair co-chaired by Archduke Georg of Austria-Hungary which celebrated the enlargement of the European Union.[151] Bob Hope was such a regular performer at the Ballroom that he said, "I've played so many dinners in the Grand Ballroom, I always make a crack when I get up to speak that I leave my dinner jacket in the lobby so that I don't have to ship it to the Coast all the time".[83] Of note in the Astor Gallery are 12 allegorical females, painted by Edward Emerson Simmons.[152] Every October, the Paris Ball was held in the Grand Ballroom, before moving to the Americana (now the Sheraton Center).[153] It hosted a memorable New Year's Eve party with Guy Lombardo and the Royal Canadians, and Lombardo used to broadcast live on the radio there from the "Starlight Roof". Maurice Chevalier performed at the ballroom in 1965 in his last appearance.[154] Louis Armstrong performed at the Waldorf for two weeks in March 1971. This was Armstrong's last performance.[155][156] Since 1986, most Rock & Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremonies have been held in the Grand Ballroom.[157] The Silver Corridor outside the ballroom bears a resemblance to the Peacock Alley, but is shorter and wider.[158]

The fourth floor has the banquet and sales offices, and most of the suites were named after guests including Barron, Vanderbilt, Windsor, Conrad, Vertès, Louis XVI, and Cole Porter. The fourth floor was where the notorious Sunday-night card games were played.[159] Before its 2021 renovation, the hotel had a model of one of the living rooms of apartment 31A, then the suite of former U.S. President Herbert Hoover. A living room from the suite is also recreated as a display at the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum in West Branch, Iowa.[160][161]

Rooms and suites

The Waldorf Astoria and Towers has a total of 1,413 hotel rooms as of 2014.[1] In 2009, when it had 1,416 rooms, the main hotel had 1,235 single and double rooms and 208 minisuites, 17 of which were classified as "Astoria Level", which are upgraded rooms with deluxe amenities and complimentary access to the Astoria Lounge.[26] The Waldorf Towers, from the 28th floor up to the 42nd, had 181 rooms, of which 115 were suites, with one to four bedrooms.[26] As of the late 1990s, the hotel had a housekeeping staff of nearly 400, with 150-day maids and 24-night maids.[162] The rooms retain the original Art Deco motifs, although each room is decorated differently.[26] The guests rooms, classified as Deluxe, Superior, and Luxury, feature "Waldorf Serenity" beds and have a marble bath or shower with amenities designed by Salvatore Ferragamo.[163] The suites featured king or double beds and start in size at 450 square feet (42 m2). The smallest are the one-bedroom suites, which range from 450 to 600 square feet (42 to 56 m2), then the Signature Suites have a separate living room and one or two bedrooms, which range from 750 to 900 square feet (70 to 84 m2),[164] and finally, the suites of The Towers are generally larger and costlier still, and have a twice-daily maid service.

The Tower suites are divided into standard ones, The Towers Luxury Series, which have their own sitting room, the Towers Penthouse Series, the Towers Presidential-Style Suites, and finally the most expensive Presidential Suite on the 35th floor. The Penthouse Series contains three suites, The Penthouse, The Cole Porter Suite, and The Royal Suite, named after the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. They start at 1,800 square feet (170 m2) in size, with two or more bedrooms, and are fitted with a kitchen and dining room which can accommodate for 8–12 guests.[165] The Towers Presidential-Style Suites are divided into the MacArthur Suite and the Churchill Suite, and have their own grand entry foyer. Like the Penthouse Series, they have their own kitchen and dining room.[165] The 2,250 square feet (209 m2) Presidential Suite is designed with Georgian-style furniture to emulate that of the White House.[165] It has three large bedrooms and three bathrooms, and boasts numerous treasures, including the desk of General MacArthur and rocking chair of John F. Kennedy.[166]

Other facilities

A 2,500 square feet (230 m2) fitness center is on the 5th floor. The $21.5 million Waldorf Astoria Guerlain Spa was inaugurated on September 1, 2008 on the 19th floor. It features 16 treatment rooms and two relaxation lounges.[26] The hotel has its own Business Center, a 1,150 square feet (107 m2) digital facility, where guests can access the Internet and photocopy.[26] In 2004 the hotel launched a line of products in keeping with the Art Deco style of the hotel, reportedly becoming the first individual hotel in the world to have its own merchandise collection.[167]

Secret railway track

The hotel has its own railway platform, Track 61, that was part of the New York Central Railroad (later Metro-North Railroad), and was connected to the Grand Central Terminal complex. The platform was used by Franklin D. Roosevelt, James Farley, Adlai Stevenson, and Douglas MacArthur, among others. The platform was also used for the exhibition of American Locomotive Company's new diesel locomotive in 1946. In 1948, Filene's and the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad also staged a fashion show on the platform.[168] An elevator large enough for Franklin D. Roosevelt's automobile provides access to the platform.[1][169] There is a pedestrian entrance from E 50th St., just to the left of the Waldorf Towers entrance. However, it is rarely opened to the public.[168][170][171][172]

Restaurants and cuisine

The Waldorf Astoria was the first hotel to offer room service and was the first major hotel in the world to hire women as chefs, beginning in 1931.[173][174] An extensive menu is available for guests, with special menus for children and for dieters.[26] The executive chef of the Waldorf for many years was John Doherty, following the Austrian Arno Schmidt who held the position for ten years from 1969 to 1979.[145][175] Restaurateur George Lang was awarded the Hotelman of the Year Award in 1975.[176] As of the early 1990s, the hotel served over three million dishes a year and got through 27,000 pounds of lobster, 100 pounds of beluga caviar, 380,000 pints of strawberries annually.[177] The hotel has gained significant renown for its lavish feasts. During one grand feast for Francis Cardinal Spellman, over 200 VIP guests, according to Arno Schmidt, devoured some 3,600 pounds of fillet, 600 pounds of fresh halibut, 1,500 pounds of potatoes, and 260 pounds of petit fours, eaten on gold china plates.[178] One 1973 feast by the Explorer's Club devoured hippo meat, a 4-foot (1.2 m) alligator, a baby shark, an amberjack tuna, a boa, wild boar hams, 480 pieces of breaded-fried cod tongues and cheeks, antelope steaks, two boxes of Chinese rabbit, and 20 pounds of rattlesnake.[179]

The hotel has three main restaurants, Peacock Alley, The Bull and Bear Steak House, and Oscar's Brasserie, as well as a secondary restaurant, the Japanese Inagiku. At its peak in the late 1940s, the hotel once had nine restaurants.[180] Peacock Alley, situated in the heart of the lobby, features an Art Deco design with gilded ceilings and includes the main restaurant, a bar and lounge, and three private dining salons. It is known primarily for its fish and seafood dishes.[26] Sunday Brunch is particularly popular with locals and features over 180 gourmet dishes divided into 12 themed displays, with cuisine ranging from lobster and oysters to Belgian waffles, Eggs Benedict, and omelettes to hollandaise sauces.[26] The Bull and Bear Steak House is furnished in richly polished mahogany in the English Regency style,[181] and has a "den-like" atmosphere,[24] and is reportedly the only restaurant on the East Coast which serves 28 days prime grade USDA Certified Angus Beef.[26] It has won awards from the National Restaurant Association and Holiday magazine.[182] Between 2007 and 2010, the restaurant was the filming location for Fox Business Happy Hour, presented live between 5 and 6 pm. The Bull and Bear Bar is based on the original Waldorf Astoria Bar, which was a favorite haunt of many of the financial elite of the city from the hotel's inception in 1893, and adventurers such as Diamond Jim Brady, Buffalo Bill Cody and Bat Masterson.[183] Behind the bar are bronze statues of a bull and a bear, which represent the successful men of Wall Street. The Inagiku, meaning the "rice chrysanthemum",[184] serves contemporary Japanese cuisine. The restaurant opens for lunch on weekdays and cocktails and dinner in the evenings. Designed by Henry Look of San Francisco, the restaurant has four "distinctly different" rooms, including one which represents an old Japanese farmhouse, and the Kinagu Room, resembling a Japanese temple.[184] Guests have the option to reserve private orthodox tatami rooms.[26]

Oscar's Brasserie, overlooking Lexington Avenue in what was once a Savarin restaurant, is designed by Adam Tihany.[26] The restaurant takes its name from Oscar Tschirky (Oscar of the Waldorf) and serves traditional American cuisine, with many dishes based upon his cookbook which have gained world renown, including the Waldorf salad, Eggs Benedict, Thousand Island dressing, and Veal Oscar.[26][185] The Waldorf salad—a salad made with apples, walnuts, celery, grapes, and mayonnaise or a mayonnaise-based dressing—was first created in 1896 at the Waldorf by Oscar.[186] The original recipe, however, did not contain nuts, but they had been added by the time the recipe appeared in The Rector Cook Book in 1928. Tschirky was also noted for his "Oscar's Sauce", which became so popular that it was sold at the hotel.[187] Another of the hotel's specialties was red velvet cake, which became one of its most popular desserts.[188]

Sir Harry's Bar is one of the principal bars of the hotel, situated just off the main lobby. It is named after British Sir Harry Johnston (1858–1927). In the 1970s the bar was renovated in a "plush African safari" design to honor Johnston, a notable explorer of Africa, with "zebra-striped wall coverings and carpeting, with bent-cane furnishings".[185] It has since been redecorated back to a more conservative design, with walnut paneling and leather banquettes, and featured a 23 feet (7.0 m) by 8 feet (2.4 m) ebony bar as of the early 1990s.[184] Frank Sinatra frequented Sir Harry's Bar for many years. In 1991, while drinking at Sir Harry's with Jilly Rizzo and Steve Lawrence, he was approached by a fan asking for an autograph. Sinatra responded, "Don't you see I'm on my own time here? You asshole. What's wrong with you?" The fan said something which angered Sinatra, who lunged at the fan, and Sinatra had to be restrained.[189]

Cocktail books

Albert Stevens Crockett, the hotel's veteran publicist and historian, wrote his first cocktail book "Old Waldorf Bar Days" in 1931 during Prohibition and the construction of the current hotel on Park Avenue. It was an homage to the original hotel and its famous bar and clientele. The book contains Crockett's takes on the original hand-written leather-bound book of recipes that was given to him at the time of the closure by bartender Joseph Taylor. This edition was never reprinted.[190]

In 1934, Crockett wrote a second book, "The Old Waldorf Astoria Bar Book", in response to the repeal of the Volstead Act and the end of the Prohibition era. He edited out most of the text from the first book. Drawing from his experiences as a travel writer, Crockett added nearly 150 more recipes, the bulk of which can be found in the "Cuban Concoctions" and "Jamaican Jollifers" chapters. These books became reference books on the subject of pre-Prohibition cocktails and their culture.[191]

In 2016, the long-time hotel bar manager of Peacock Alley and La Chine, Frank Caiafa, added a completely new edition to the canon. Caiafa's "The Waldorf Astoria Bar Book" includes all of the recipes in Crockett's books; many of the hotel's most important recipes created since 1935; and his own creations.[192][193] In 2017, it was nominated for a James Beard Foundation Award for Best Beverage Book.[194]

Other notable books with connections to the hotel include "Drinks" (1914) by Jacques Straub, a wine steward and friend of Oscar Tschirky who had written about the first hotel's notable recipes.[195] Tschirky himself compiled a list of 100 recipes for his own book "100 Famous Cocktails" (1934), a selection of favorites from Crockett's books.[196] Finally, hotel publicist Ted Saucier wrote "Bottoms Up" in 1951, consisting of a compendium of popular, national recipes of the day.[197]

Notable residents and guests

Leaders and businesspeople

On the 100th anniversary of the hotel in 1993, one publication wrote: "It isn't the biggest hotel in New York, nor the most expensive. But when it comes to prestige, the Waldorf-Astoria has no peer. When presidents come to New York, they stay at the Waldorf-Astoria. Kings and queens make it their home away from home, as have people as diverse as Cary Grant, the Dalai Lama and Chris Evert. Some of them liked the hotel so well, they made their home there."[198] From its inception, the Waldorf was always a "must stay" hotel for foreign dignitaries. The viceroy of China, Li Hung Chang stayed at the hotel in 1896 and feasted on hundred-year-old eggs which he brought with him.[21] Over the years many royals from around the world stayed at the Waldorf Astoria including Shahanshah of Iran and Empress Farah, King Frederick IX and Queen Ingrid of Denmark, Princess Astrid of Norway, Crown Prince Olav and Crown Princess Martha of Norway, King Baudouin I of Belgium and Queen Fabiola, Prince Albert and Princess Paola of Belgium, King Hussein I of Jordan, Prince Rainier III and Princess Grace of Monaco, Queen Juliana of the Netherlands, King Michael of Romania, Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip of the Commonwealth realms, Mohammed Zahir Shah and Homaira Shah of Afghanistan, King Bhumibol Adulyadej and Queen Sirikit of Thailand, and Crown Prince Akihito and Princess Michiko of Japan, and many others.[199] Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip stayed at the hotel during their first visit to America on October 21, 1957, and a banquet was held for them in the Grand Ballroom. In the Bicentennial year in 1976, most of the heads of state from around the world and all of the Kings and Queens of Europe were invited to the hotel, and it also served the presidential candidates in the run up to the elections of that year.[200]

In modern times, the clientele of the Waldorf is more typically wealthy politicians and businessmen than playboys and royalty.[201] An entire floor was often rented out to wealthy Saudi Arabians with their own staff. Wealthy Japanese businessmen during their stay would sometimes remove the furniture and replace it with their own floor mats.[158] One early wealthy resident was Chicago businessman J. W. Gates who would gamble on stocks on Wall Street and play poker at the hotel. He paid up to $50,000 a year to hire suites at the hotel.[202] Princess Victoria Melita of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha was invited by Waldorf president Lucius Bloomer to stay at the hotel in the 1920s.[203] Demands by people of prominence could often be exorbitant or bizarre, and Fidel Castro once walked into the hotel with a flock of live chickens, insisting that they be killed and freshly cooked on the premises to his satisfaction, only to be turned away.[204] While serving as Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger ordered all of the antiques to be removed from one suite and replaced with 36 desks for his staff. An unnamed First Lady also once demanded that all of the bulbs in her suite be changed to 100-watt ones and kept on all day and night to simulate daylight; she further insisted that there be an abundance of chewing gum available.[205]

Postmaster General James Farley occupied two adjoining suites in the current Waldorf Astoria during his tenure as the chairman of the board of Coca-Cola's International division from 1940 until his death in 1976, arguably one of the landmark's longest housed tenants.[206] The Presidential Suite at the hotel come from when, during the 1950s and early 1960s, former U.S. president Herbert Hoover and retired U.S. General Douglas MacArthur lived in suites on different floors of the hotel. Hoover lived at the Waldorf Astoria for over 30 years from after the end of his presidency[160] until he died in 1964;[166] former President Dwight D. Eisenhower lived there between 1967 and his death in 1969.[207] MacArthur's widow, Jean MacArthur, lived there from 1952 until her death in 2000. A plaque affixed to the wall on the 50th Street side commemorates this. John F. Kennedy was fond of the Waldorf Astoria and had a number of private meetings at the hotel, including one with Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion.[208] Since Hoover, every President of the United States has either stayed over or lived in the Waldorf Astoria, although Jimmy Carter claimed to have never stayed overnight at the hotel.[160][209] Nancy Reagan was reputedly not fond of the Presidential Suite.[210][211]

The official residence of the United States' Permanent Representative to the United Nations, an unnamed 42nd-floor apartment, was located in the Waldorf Towers for many years. On June 17, 2015, however, the US Department of State announced that it was moving its headquarters during meetings of the UN General Assembly to The New York Palace Hotel.[212]

Carlos P. Romulo, Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Philippines and member of the UN had suite 3600, below Hoover's, for some 45 years from 1935 onwards, and former Philippine First Lady Imelda Marcos also spent much time and money at the hotel.[213] Another connection with the Philippines is that many meetings were held here between President Manuel L. Quezon and high ranking American politicians and senators. Through the meetings, Quezon encouraged investment into the country and convinced General MacArthur to accompany him back to the Philippines as his military adviser.[214]

Nicaraguan president Anastasio Somoza Debayle and his wife Hope Portocarrero had a penthouse suite at the Waldorf Towers, where Somoza received political leaders.[215]

Celebrities

The hotel has had many well-knowns under its roof throughout its history, including Charlie Chaplin, Ava Gardner, Liv Ullmann, Edward G. Robinson, Gregory Peck, Ray Bolger, John Wayne, Tony Bennett, Jack Benny, Katharine Hepburn, Spencer Tracy, Muhammad Ali, Vince Lombardi, Judy Garland, Sonny Werblin, Greer Garson, Harold Lloyd, Liberace, Burt Reynolds, Robert Montgomery, Cesar Romero, and many others.[216] Due to the number of high-profile guests staying at the hotel at any one time, author Ward Morehouse III has referred to the Towers as a "kind of vertical Beverly Hills. On any one given night you might find Dinah Shore, Gregory Peck, Frank Sinatra [or] Zsa Zsa Gabor staying there".[217] Gabor married Conrad Hilton in 1941. [201]

During the 1930s, gangster Benjamin "Bugsy" Siegel owned an apartment at the Waldorf,[218] and Frank Costello was said to have got his haircut and nails done in the Barber's Shop at the Waldorf.[83] Around the time of World War I, inventor Nikola Tesla lived in the earlier Waldorf-Astoria.[219]

In 1955, Marilyn Monroe and her husband, Arthur Miller[220] stayed at the hotel for several months,[221] but due to costs of trying to finance her production company "Marilyn Monroe Productions", only being paid $1,500 a week for her role in The Seven Year Itch and being suspended from 20th Century Fox for walking out on Fox after creative differences, living at the hotel became too costly and Monroe had to move into a different hotel in New York City. Around the same time that Monroe lived in the hotel, Cole Porter and his wife Linda Lee Thomas had an apartment in the Waldorf Towers, where Thomas died in 1954. Porter's 1934 song "You're the Top", contains the lyric, "You're the top, you're a Waldorf salad". The Cole Porter Suite, Suite 33A, was the place where Porter lived and entertained for a period. Frank Sinatra paid nearly $1 million a year to keep it as his suite at the hotel between 1979 and 1988, which he called home when out of Los Angeles.[222] Sinatra took over part of the hotel during the filming of The First Deadly Sin in 1980.[223]

Grace Kelly and Rainier III were regular guests at the hotel. At one time Kelly was reputed to be in love with the hotel banquet manager of the Waldorf, Claudius Charles Philippe.[224] Elizabeth Taylor frequented the hotel, and would often attend galas at the hotel to talk about her various causes. Her visits were excitedly awaited by the hotel staff, who would prepare long in advance.[225] Taylor was honored at the 1983 Friars Club dinner at the hotel.[226]

Brooke Shields has stated that her very first encounter with the paparazzi was in the Grand Ballroom of the Waldorf at the age of 12, stating that she "stood like a statue wondering why they were all hired to photograph me", and that she "debuted at the Waldorf". [227] During her childhood in the 1980s and 1990s, Paris Hilton lived with her family in the hotel.[228]

.jpg.webp)

One of the most prestigious debutante balls in the world is the invitation-only International Debutante Ball held biennially in the Grand Ballroom at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel, where girls from prominent world families are presented to high society.[lower-alpha 2][lower-alpha 3] Since 1954 the musical entertainment at the ball has traditionally been provided by the musicians of the Lester Lanin Orchestra.[234][235]

In popular culture

The Waldorf Astoria has been a filming location for numerous films and TV series. Ginger Rogers headlined an all star ensemble cast in the 1945 film Week-End at the Waldorf, set at the hotel and filmed partially on location there.[14][22] Other films shot at the hotel include The Out-of-Towners (1970), Broadway Danny Rose (1984), Coming to America (1988), Scent of a Woman (1992), The Cowboy Way (1994), Random Hearts (1999), Analyze This (1999), For Love of the Game (1999), Serendipity (2001), The Royal Tenenbaums (2001), Maid in Manhattan (2002), Two Weeks Notice (2002), Catch Me If You Can (2002), End of the Century (2005), Mr. and Mrs. Smith (2005), The Pink Panther (2006), and The Hoax (2006).[26] Television series that have filmed at the Waldorf include Law and Order, Rescue Me, Sex and the City, The Sopranos and Will and Grace.[26]

Several biographies have been written about the Waldorf, including Edward Hungerford's Story of the Waldorf (New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1925) and Horace Sutton's Confessions of a Grand Hotel: The Waldorf-Astoria (New York: Henry Holt, 1953).[236] Langston Hughes wrote a poem entitled "Advertisement for the Waldorf-Astoria", criticizing the hotel and inviting the jobless and homeless to take over the space of the hotel.[237] Wallace Stevens wrote a poem entitled "Arrival at the Waldorf", in which he contrasts the wild country of the jungles of Guatemala to being "back at the Waldorf". In Meg Cabot's novel Jinx, the Chapman School Spring Formal takes place in the Waldorf-Astoria. It is at this point that Tory (the main antagonist) reveals Jean's first attempt at a love spell, which catalyzed the novel's events.[238]

Waldorf of the Muppets series was named after the hotel. In the episode starring Dizzy Gillespie his heckling partner Statler (named after Statler Hilton, also in Manhattan) couldn't make it due to illness so Waldorf's wife Astoria came with him.[239] Ayn Rand biographer Anne Heller wrote that the Waldorf Astoria inspired the "Wayne-Falkland Hotel" in Rand's novel Atlas Shrugged.[240]

See also

- List of hotels in New York City

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan from 14th to 59th Streets

- List of tallest buildings in New York City

- The Waldorf–Astoria Orchestra

- List of residences of presidents of the United States

References

Explanatory notes

- Professor Elazar L. Sukenik was first offered the scrolls in 1947 by an antiquities dealer in Bethlehem. Because of the recent partitioning of Palestine, Jews were not permitted to travel there. Sukenik disguised himself as an Arab to travel to the city. He was allowed to examine the scrolls and to take a small fragment of one for testing. When he made the trip back to Bethlehem to purchase them the next day, he found that the dealer had been pressured into selling them to the Syriac Orthodox Church. Archbishop Mar Samuel offered to sell them to Sukenik for US$125,000; before the transaction could take place, Mar Samuel's life was threatened and he fled to the United States. Sukenik died in 1953 without a further word about the whereabouts of the scrolls.[69] In 1954, a classified ad appeared in The Wall Street Journal offering to sell the four scrolls.[70] Yigael Yadin, the son of Professor Sukenik, was visiting the United States when the ad appeared and someone brought it to his attention. The State of Israel then planned to secretly buy the scrolls.[69]

- These include aristocrats Princess Katarina of Yugoslavia, Vanessa von Bismarck (great-great-granddaughter of Otto von Bismarck), Princess Natalya Elisabeth Davidovna Obolensky (granddaughter of the Prince Ivan Obolensky, the chairman of the International Debutante Ball), Princess Ines de Bourbon Parme, Countess Magdalena Habsburg-Lothringen (great-great-granddaughter of Empress Elisabeth 'Sisi' of Austria) and Lady Henrietta Seymour (daughter of the Duke and Duchess of Somerset and descendant of Henry VIII's wife Jane Seymour).[229]

- Untitled elites include Tricia Nixon,[230] Julie Nixon, Jennie Eisenhower, Ashley Walker Bush (granddaughter of President George H. W. Bush and niece of President George W. Bush), Lucinda Robb (granddaughter of President Lyndon B. Johnson), Christine Colby (daughter of CIA director William Colby),[231] Hollister Knowlton (future wife of CIA director David Petraeus),[232] Charlotte and Catherine Forbes (granddaughters of Malcolm Forbes) and Christina Huffington (daughter of Arianna Huffington of the Huffington Post) have all been invited to the ball.[229] Ivanka Trump (daughter of President Donald Trump) and Sasha and Malia Obama (daughters of President Barack Obama) have also been invited to be presented as debutantes at the International Debutante Ball.[233]

Citations

- Bagli, Charles V. (October 7, 2014). "Waldorf-Astoria to Be Sold in a $1.95 Billion Deal". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 27, 2019. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- "Emporis building ID 115502". Emporis. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016.

- "Waldorf Astoria New York". SkyscraperPage.

- Waldorf Astoria New York at Structurae

- Flippin 2011, p. 34.

- Bernardo 2010, p. 40.

- 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- Emmerich 2013, p. 7.

- "The Waldorf-Astoria". Edwardianpromenade.com. April 27, 2009. Archived from the original on April 14, 2014. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- Schwartz 2009, p. 103.

- "Waldorf Astoria Drops the Equals Sign We'd Barely Noticed". HotelChatter. February 10, 2009. Archived from the original on June 15, 2013. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- Hirsh 1997, p. 61.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 20.

- "Hotel history". Waldorfnewyork.com. Archived from the original on November 27, 2013. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 132.

- Morrison 2014, p. 11.

- Seifer 1998, p. 204.

- "Waldorf-Astoria to give way to office". Lincoln Evening Journal. Lincoln, Nebraska. December 21, 1928. p. 13. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved October 20, 2015 – via newspapers.com

.

. - "Hotel World Known". New York Tribune. New York, New York. February 3, 1918. p. 1. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved October 20, 2015 – via newspapers.com

.

. - Bishop, Jim (January 26, 1958). "Anger, Spite Tint History of the Waldorf". The Salt Lake Tribune. Salt Lake City, Utah. p. 2. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved October 20, 2015 – via newspapers.com

.

. - Morehouse III 1991, p. 21.

- "Guard shot during robbery attempt at Waldorf-Astoria". CNN. October 17, 2004. Archived from the original on December 10, 2008. Retrieved January 2, 2015.

- "The Waldorf Astoria". New York Architecture. Archived from the original on September 9, 2013. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 8.

- Cashman 1988, p. 373.

- "Hotel fact sheet" (PDF). New York University School of Professional Studies. 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 18, 2015. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 18.

- Smith 2007, p. 595.

- Tschirsky, Oscar (October 5, 1937). "The Voice of Broadway". The Bee. Danville, Virginia. p. 6. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved October 20, 2015 – via newspapers.com

.

. - Tschirsky, Oscar (October 5, 1937). "The Voice of Broadway". The Bee. Danville, Virginia. p. 12. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved October 20, 2015 – via newspapers.com

.

. - Nasaw 2007, p. 841.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 32.

- "High Life in Gotham". Indiana Weekly Messenger. Indiana, Pennsylvania. September 20, 1899. p. 1. Archived from the original on November 30, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2015 – via newspapers.com

.

. - "Banquet in honor of Frederick A. Cook, M.D., by the Arctic Club of America, Sept. 23, 1909, Waldorf-Astoria, N.Y." Library of Congress. Archived from the original on October 24, 2020. Retrieved January 13, 2014.

- "Congratulatory addresses delivered at a complimentary dinner tendered to Judge Elbert H. Gary at the Waldorf-Astoria, New York City, October 15th, 1909". Internet Archive. Retrieved January 13, 2014.

- Kuntz & Smith 1998, p. 77.

- "Six Degrees of Titanic". History.com. Archived from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- "The U.S. Senate Inquiry". Titanic Inquiry Project. Archived from the original on April 7, 2012. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- Ward 2012, p. 146.

- "Sherry's To Move May 17; Fifty-Eighth Street Plan Modified by 'Prohibition and Bolshevism'". The New York Times. May 17, 1919. p. 28. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- Klein 2005, p. 25.

- "Busy Week For Radio Station WDAF-Chillicothe Music Co. To Get Programs". The Chillicothe Constitution-Tribune. Chillicothe, Missouri. November 15, 1925. p. 1. Archived from the original on January 10, 2019. Retrieved October 20, 2015 – via newspapers.com

.

. - "1927 Victor Series Will Open With World Famous Artist". The Indianapolis News. Indianapolis, Indiana. January 1, 1927. p. 7. Archived from the original on January 10, 2019. Retrieved October 20, 2015 – via newspapers.com

.

. - "New Company Takes Over NBC Blue Net". The Fresno Bee Republican. January 10, 1942. p. 5.

- Blanke 2002, p. 121.

- Bishop, Jim (January 28, 1958). "From Depths of Debt Rose Pinnacle of Hostelry". The Salt Lake Tribune. Salt Lake City, Utah. p. 14. Archived from the original on January 10, 2019. Retrieved October 20, 2015 – via newspapers.com

.

. - Bishop, Jim (January 28, 1958). "From Sea of Red Ink, Tears, Rose New Waldorf Tower". The Salt Lake Tribune. Salt Lake City, Utah. p. 18. Archived from the original on April 10, 2019. Retrieved October 20, 2015 – via newspapers.com

.

. - Robins, A.W.; New York Transit Museum (2013). Grand Central Terminal: 100 Years of a New York Landmark. ABRAMS. p. 150. ISBN 978-1-61312-387-4. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved December 6, 2018.

- Korom 2008, p. 422.

- Morrison 2014, p. 105.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 40.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 46-7.

- "Lucius Boomer, 68, Waldorf Director, is Dead in Norway". The Kingston Daily Freeman. Kingston, New York. July 26, 1947. p. 1. Archived from the original on January 10, 2019. Retrieved October 20, 2015 – via newspapers.com

.

. - Morehouse III 1991, p. 259.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 215.

- Harker 2007, p. 47.

- Schweber 2009, p. 115.

- Turback, Michael (2018). What a Swell Party It Was!: Rediscovering Food & Drink from the Golden Age of the American Nightclub. Skyhorse Publishing. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-5107-2779-3. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2018.

- Studwell, William E.; Baldin, Mark (2000). The Big Band Reader: Songs Favored by Swing Era Orchestras and Other Popular Ensembles. Resources in music history. Haworth Press. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-7890-0914-2. Retrieved December 11, 2018.

- "On The Stand - Eddy Duchin at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel". Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. December 4, 1948. p. 39. Archived from the original on February 18, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2018.

- Harbutt 1988, p. 3.

- Morehouse III 1991, pp. 176, 185.

- Bresler 2004, p. 169.

- Porter 2010, p. 149.

- Sorin 2002, p. 109.

- Carroll 2006, p. 25.

- Marmorstein, Gary. The Label: The Story of Columbia Records. Thunder's Mouth Press. p. 165.

- Sehlstedt, Jr. Albert (March 22, 1992). "Harry M. Orlinsky, 84, leading biblical scholar". The Baltimore Star. Baltimore, Maryland. Archived from the original on January 19, 2015.

- Isaacs, Marty (November 1, 1992). "The Man Who Bought the Dead Sea Scrolls". Contemporary Review. Archived from the original on January 20, 2015. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- "Classified ad offering the sale of the four Dead Sea Scrolls". The Wall Street Journal. 1954. Archived from the original on January 19, 2015.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 125.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 126.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 226.

- LIFE. Time Inc. May 23, 1960. p. 90. ISSN 0024-3019.

- Avery 2010, p. 50.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 225.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 235.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 227.

- LIFE. Time Inc. May 6, 1957. p. 201. ISSN 0024-3019.

- King 2011, p. 427.

- LIFE. Time Inc. December 8, 1958. p. 137. ISSN 0024-3019.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 230.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 254.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 218.

- Rothman, Lily (September 21, 2015). "The First Time a Pope Visited the U.S. Was Much More Complicated". Time. Archived from the original on April 16, 2020.

- Fletcher 2010, p. 376.

- "The Who Setlist at Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony No. 5". Setlist.fm. Archived from the original on June 30, 2019. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- Dana 2011, p. 227.

- Taraborrelli 2014, p. 118.

- Stanley Turkel (1931). "A New Waldorf Against The Sky". Old and Sold. Archived from the original on March 21, 2013. Retrieved February 26, 2011.

- "New York Luxury Hotels & 5 Star Vacations – The Waldorf Astoria New York Legacy". Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- "Motorcade". San Antonio Express. San Antonio, Texas. November 13, 1974. p. 1. Archived from the original on October 21, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2015 – via newspapers.com

.

. - "President Views Energy". The Times Recorder. Zanesville, Ohio. December 11, 1974. p. 1. Archived from the original on October 21, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2015 – via newspapers.com

.

. - Morehouse III 1991, pp. 185–6.

- Littman 1987, p. 155.

- "The Birth of the IBM PC". IBM. Archived from the original on January 2, 2014. Retrieved January 19, 2014.

- Fizel 2012, p. 41.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 57.

- "Ambassador Edward P. Djerejian to Speak at Waldorf-Astoria Banquet on Sunday, May 27". The Armenian Reporter. May 5, 2001. Archived from the original on March 29, 2015. Retrieved January 20, 2015 – via HighBeam Research (subscription required).

- "Ben Affleck at the 5th Annual DGA Honors Gala, held at the Waldorf Astoria in New York, Wednesday, September 29, 2004". KRT Photos. September 29, 2004. Archived from the original on March 29, 2015. Retrieved January 20, 2015 – via HighBeam Research (subscription required).

- Knight 2014, p. 923.

- "Hilton considers building Waldorf-Astoria in Vegas". International Herald Tribune. accessed via HighBeam Research (subscription required). December 15, 2006. Archived from the original on March 29, 2015. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- "The Waldorf=Astoria Collection Announces the Opening of the Legendary Hotel Brand's First Guerlain Spa at the Waldorf=Astoria Hotel in New York City.(Company overview)". Biotech Week. accessed via HighBeam Research (subscription required). October 8, 2009. Archived from the original on March 29, 2015. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- Frank, Robert (October 6, 2014). "Waldorf becomes most expensive hotel ever sold: $1.95 billion". CNBC. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- Strum, Beckie. "Hilton VP Says Luxury Shouldn't 'Need to Be Serious'". www.mansionglobal.com. Archived from the original on September 15, 2021. Retrieved September 15, 2021.

- "Waldorf Astoria turning into condos". Reuters. July 1, 2016. Archived from the original on August 18, 2016. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

- Yakas, Ben (March 1, 2017). "Videos: Stevie Wonder Serenades Waldorf-Astoria On Its Last Night Before Closing". Gothamist. Archived from the original on May 18, 2021. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- Burke, Kerry; Greene, Leonard (February 27, 2017). "New York's Waldorf Astoria Hotel closes for major renovations". NY Daily News. Archived from the original on October 21, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2017.

- Passy, Charles (June 28, 2016). "The Feed: Waldorf Astoria Restaurants to Close". The wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

- Hurowitz, Noah (March 7, 2017). "Midtown & Theater District Real Estate Waldorf Astoria Interiors Landmarked Days After Closure for Renovations". Dnainfo. Archived from the original on March 12, 2017. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- "Waldorf Astoria interiors are now NYC landmark". The Real Deal New York. March 7, 2017. Retrieved August 1, 2022.

- Plitt, Amy (June 11, 2019). "Waldorf Astoria's 375 new condos to hit the market this fall". Curbed NY. Archived from the original on October 9, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2019.

- Morris, Keiko (June 11, 2019). "Waldorf Astoria to Sell Condos, as Chinese Owners Shrug Off Glut". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on January 1, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2019.

- "Anbang taps Douglas Elliman to market Waldorf Astoria condos". The Real Deal. June 11, 2019. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2019.

- "After a $1 Billion Renovation, the Waldorf Astoria Is Reopening—and You Can Now Live There". www.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved November 21, 2019.

- "Top 10 Secrets of The Waldorf Astoria Hotel in NYC". Untapped New York. March 16, 2021. Archived from the original on September 15, 2021. Retrieved March 17, 2021.