Walter Krueger

Walter Krueger (26 January 1881 – 20 August 1967) was an American soldier and general officer in the first half of the 20th century. He commanded the Sixth United States Army in the South West Pacific Area during World War II. He rose from the rank of private to general in the United States Army.

Walter Krueger | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 26 January 1881 Flatow, West Prussia, German Empire |

| Died | 20 August 1967 (aged 86) Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, United States |

| Buried | Arlington National Cemetery, Virginia, United States |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service/ | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1898–1946 |

| Rank | General |

| Service number | 0-1531 |

| Unit | Infantry Branch |

| Commands held | Sixth Army Southern Defense Command Third Army VIII Corps 2nd Infantry Division 16th Brigade 6th Infantry Regiment 55th Infantry Regiment |

| Battles/wars | Spanish–American War Philippine–American War Mexican Revolution World War I World War II |

| Awards | Distinguished Service Cross Army Distinguished Service Medal (3) Navy Distinguished Service Medal Legion of Merit |

Born in Flatow, West Prussia, German Empire, Krueger emigrated to the United States as a boy. He enlisted for service in the Spanish–American War and served in Cuba, and then re-enlisted for service in the Philippine–American War. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant in 1901. In 1914 he was posted to the Pennsylvania Army National Guard. His regiment was mobilized on 23 June 1916 and served along the Mexican border. After the United States commenced hostilities with Germany in April 1917, Krueger was assigned to the 84th Infantry Division as its Assistant Chief of Staff G-3 (Operations), and then its chief of staff. In February 1918, he was sent to Langres to attend the American Expeditionary Force General Staff School, and in October 1918, he became chief of staff of the Tank Corps.

Between the wars, Krueger served in a number of command and staff positions, and attended the Naval War College at his own request. In 1941, he assumed command of the Third Army, which he led in the Louisiana Maneuvers. He expected, because of his age, to spend the war at home training troops, but in 1943 he was sent to General Douglas MacArthur's Southwest Pacific Area as commander of the Sixth Army and Alamo Force, which he led in a series of successful campaigns against the Japanese.

As an army commander, Krueger grappled with the problems imposed by vast distances, inhospitable terrain, unfavorable climate, and an indefatigable and dangerous enemy. He balanced the fast pace of MacArthur's strategy with the more cautious approach of managing subordinates who often found themselves confronted by unexpectedly large numbers of Japanese troops. In 1945 at the Battle of Luzon, Krueger faced the Japanese army under Tomoyuki Yamashita and Krueger outmaneuvered his enemies like he had in the 1941 exercises. This was Krueger's largest, longest, and final battle.

Krueger retired to San Antonio, Texas, where he bought a house and wrote From Down Under to Nippon, an account of his campaigns in the Southwest Pacific. His retirement was marred by family tragedies. His son James was dismissed from the army in 1947 for conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman. His wife's health deteriorated, and she died of cancer in 1956. His daughter Dorothy stabbed her husband to death in 1952. She was sentenced to life imprisonment by a court-martial, but was freed by the Supreme Court in 1957.

Education and early life

Walter Krueger was born on 26 January 1881 in Flatow, West Prussia, then part of the German Empire,[1] now part of Poland.[2] He was the son of Julius Krüger, a Prussian landowner who had served as an officer in the Franco-Prussian War, and his wife, Anna, formerly Hasse. Following Julius's death, Anna and her three children emigrated to the United States to be near her uncle in St. Louis, Missouri. Walter was then eight years old. In St. Louis, Anna married Emil Carl Schmidt, a Lutheran minister.[3][4]

The family subsequently settled in Madison, Indiana. Krueger was tutored by his stepfather, educated in the public schools of Madison, and completed high school at Madison's Upper Seminary.[3][4] As a teenager, he wanted to become a naval officer, but when his mother objected he decided to become a blacksmith instead.[1] After graduating from high school, Krueger enrolled at the Cincinnati Technical High School, where he learned blacksmithing and completed science and mathematics courses in preparation for college studies in engineering.[3][4]

Early military service

On 17 June 1898, Krueger enlisted for service in the Spanish–American War with the 2nd United States Volunteer Infantry. He reached Santiago de Cuba a few weeks after the Battle of San Juan Hill, and spent eight months there on occupation duties, rising to the rank of sergeant. Mustered out of the volunteers in February 1899, he returned home to Ohio, planning to become a civil engineer.[5][6]

However, many of his comrades were re-enlisting for service in the Philippine–American War and in June 1899 Krueger re-enlisted as a private in M Company of the 12th Infantry. Soon he was on his way to fight Emilio Aguinaldo's Insurrectos as part of Major General Arthur MacArthur, Jr.'s 2nd Division of the Eighth Army Corps. He took part in the advance from Angeles to Tarlac, Aguinaldo's capital. But Aguinaldo had fled, and the 12th Infantry pursued him vainly all the way through Luzon's central plain to Dagupan.[5] While serving in an infantry unit in the Philippines, he was promoted to sergeant. On 1 July 1901, he was commissioned a second lieutenant and posted to the 30th Infantry on Marinduque.[7]

Krueger returned to the United States with the 30th Infantry in December 1903. The regiment moved to Fort Crook, Nebraska. In September 1904, he married Grace Aileen Norvell, whom he had met in the Philippines. They had three children: James Norvell, born on 29 July 1905; Walter Jr., born on 25 April 1910; and Dorothy Jane, who was born on 24 January 1913.[8] Both James and Walter Jr. attended the United States Military Academy, James graduating with the class of 1926, and Walter Jr. with the class of 1931.[5] Dorothy married an army officer, Aubrey D. Smith, of the class of 1930.[9]

In 1904, Krueger attended the Infantry-Cavalry School at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and upon completing the course was chosen as a Distinguished Graduate. This was followed by the Command and General Staff College in 1907. He then joined the 23rd Infantry at Fort Ontario, New York.[10] After a second tour in the Philippines, he returned to the United States in June 1909, and was assigned to Department of Languages at Fort Leavenworth as an instructor in Spanish, French and German, which he could speak fluently. He also taught National Guard officers at Camp Benjamin Harrison, Indiana, and Pine Camp, New York. He published translations of several German military texts, most notably William Balck's Tactics.[11] The book attracted the attention of the Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Major General Leonard Wood, and was widely read.[12]

World War I

With the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, Krueger was offered a post as an observer with the German Army but was forced to turn it down due to familial commitments. Instead, he was posted to the 10th Infantry of the Pennsylvania Army National Guard.[13] The regiment was mobilized on 23 June 1916 and served along the Mexican border for five months as part of the Mexican Punitive Expedition under Major General John J. Pershing, although no National Guard units fought Mexican troops. The unit was mustered out in October 1916.[14]

Afterwards, Krueger remained with the National Guard. He trained units, and helped establish a school for officers at the University of Pennsylvania. In an article in the Infantry Journal, he called for a large, national, conscript army similar to those of European countries, arguing that this would be in accord with America's democratic values.[15]

After the United States commenced hostilities against Germany in April 1917, Krueger was assigned to the 84th Infantry Division at Camp Zachary Taylor as its Assistant Chief of Staff G-3 (Operations). He became its chief of staff, with the rank of major as of 5 August 1917. In February 1918, he was sent to Langres, France, to attend the American Expeditionary Force General Staff School. All officers from divisions that were not under orders for France were ordered to return home in May 1918, but Krueger stayed on as G-3 of the 26th Infantry Division.[16]

The French Army requested that Krueger be sent home due to his German origin, and Krueger was re-posted to the 84th Division, but he soon returned to France, as the 84th Division embarked for France in August 1918. In October, he became chief of staff of the Tank Corps. After the Armistice with Germany ended the fighting in November 1918, he became assistant chief of staff of VI and IV Corps on occupation duty, advancing to the rank of temporary colonel. For his service in the war, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal in 1919.[16]

Interwar years

With the end of the war, Krueger returned to the United States on 22 June 1919 and was initially posted to the Infantry School at Fort Benning, Georgia. In 1920, he assumed command of the 55th Infantry Regiment at Camp Funston, Kansas. He reverted to his permanent rank of captain on 30 June 1920 but was promoted to the permanent rank of major the next day. He attended the Army War College, graduating in 1921, and remaining for a year as an instructor, where he taught such classes as the "Art of Command".[17]

He paid a four-month visit to Germany in 1922 as part of the War College's Historical Section, during which he examined documents related to World War I in the German War Archives. These informed his lectures on the war, and he argued that much of the German Army's effectiveness was attributable to its system of decentralized command. Krueger urged that American commanders in the field should be given wider latitude in carrying out their orders.[17]

From 1922 to 1925, Krueger served in the War Plans Division of the War Department General Staff in Washington, DC. Krueger worked on the United States color-coded war plans, particularly War Plan Green, for another war with Mexico, and War Plan Blue, for another civil war in the United States. He traveled to the Panama Canal Zone in January 1923 to report on the state of the defenses there. After he returned, he was assigned to the Joint Army and Navy Planning Committee, an organ of the Joint Army and Navy Board responsible for coordinating war plans between the two services.[18]

While with the Joint Planning Committee, he worked on War Plan Orange, the plan for a war with Japan, and War Plan Tan, for a war with Cuba.[18] Krueger considered the problems of inter-service cooperation. At his own request, he attended the Naval War College at Newport, Rhode Island, in 1925 and 1926. He continued to ruminate on the nature of command. "Doctrine", he wrote, "knits all the parts of the military force together in intellectual bonds."[19]

Krueger came to feel the prospects for promotion in the infantry were very poor, and in 1927 he tried to transfer to the United States Army Air Corps. He attended the Air Corps Primary Flying School at Brooks Field, Texas, but suffered an attack of neuritis in his right arm, and his flight instructor, Lieutenant Claire Lee Chennault, failed him. In December 1927, he was offered a position as an instructor at the Naval War College, where he taught classes on World War I, and on joint operations.[20][21]

In June 1932, Krueger became commander of the 6th Infantry Regiment at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri, where he was promoted to colonel again on 1 August 1932.[22] Now aged 51, he became resigned to retiring as a colonel,[23] but in 1934 he returned to the War Plans Division, becoming chief of the division in May 1936,[24] and was promoted to temporary brigadier general in October 1936. In September 1938, Krueger went to Fort George G. Meade, Maryland, as commander of the 16th Infantry Brigade.[24]

He was promoted to temporary major general in February 1939, when he became commander of the 2nd Infantry Division at Fort Sam Houston, Texas.[25] The 2nd Infantry Division was at the time being used as the Proposed Infantry Division (PID). With Lesley J. McNair as commander of the 2nd Division Artillery and chief of staff of the PID, the PID tested of the US Army's new triangular division concept. As a result of the lessons learned from the PID's training and exercises, Krueger was able to offer recommendations for improvements to the triangular division concept, including taking advantage of mechanization and fast-paced tactics. The troops who took part in the PID experiment called themselves the "Blitzkruegers"; the triangular division model was adopted, and became the Army's standard design for infantry divisions in World War II.[26]

World War II

Training in the United States

Krueger became commander of IX Corps on 31 January 1940. This corps was created to control units of the Third Army engaged in large scale maneuvers in 1940,[27] in which Krueger's IX Corps conducted a series of mock battles against Walter Short's IV Corps.[28] On 27 June, Krueger became commander of the VIII Corps.[29] On 16 May 1941, he was promoted to lieutenant general, in command of the Third Army. He also became commander of the Southern Defense Command on 16 July 1941. Krueger asked for—and got—Colonel Dwight D. Eisenhower assigned to him as his chief of staff.[30]

The Louisiana Maneuvers pitted Krueger's Third Army against Lieutenant General Ben Lear's Second Army.[31] The maneuvers were a test ground for doctrine and equipment, and gave senior commanders experience in maneuvering their formations. In the first phase, Krueger quickly proved himself to be the more modern general. He responded adroitly to a changed battle situation by re-orienting his front from northeast to northwest, and was able to inflict a series of reverses on Lear's forces.[31]

In the second phase, Krueger had a superior force, and had to advance on Shreveport, Louisiana.[32] Lear's forces conducted a stubborn withdrawal, demolishing bridges in order to slow Krueger down. Krueger responded by sending Major General George S. Patton, Jr.'s 2nd Armored Division on a wide flanking maneuver through Texas.[33] Afterwards, Eisenhower became the head of the War Plans Division, and was replaced as Krueger's chief of staff by Colonel Alfred M. Gruenther. After he too was transferred, Krueger replaced him with Colonel George B. Honnen.[30]

Krueger wrote to a friend that

There's nothing that I should like better than to have a command at the front. I should love to try to "rommel" Rommel. However, I am sure that younger men will be selected for tasks of that nature, in fact for all combat commands. I shall be 62 this coming January [1943], and though I am in perfect health, can stand a lot of hardship and people tell me I look and act ten years younger, I do not delude myself.[34]

Sixth Army

It therefore came as a surprise when Krueger was informed that a theater commander had requested his services.[35] General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander of the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA), said that he was "especially anxious to have Krueger due to my long and intimate association with him".[36] This too came as a surprise to Krueger; while the two men had known each other for forty years, and Krueger had been chief of the War Plans Division when MacArthur was chief of staff, the two had never been close.[36]

The War Department approved Krueger's transfer to SWPA, but did not approve MacArthur's request for Third Army headquarters. There were only three American divisions in SWPA: the 32nd Infantry Division at Rockhampton, Queensland, the 41st Infantry Division in the Buna area in Papua, and the 1st Marine Division in Melbourne, Victoria. The 1st Cavalry Division and the 24th Infantry Division were scheduled to arrive in 1943, and other divisions would follow in 1944, but for the time being there were many fewer troops than an army would normally control. The War Department therefore saw no need for a full strength army headquarters. Instead, Krueger had to make do with a skeleton staff of a new Sixth Army, which was activated in January 1943, with less than half the establishment strength of an army headquarters.[37]

Krueger took with him several key members of the Third Army staff, including Brigadier General George Honnen as chief of staff, Colonel George H. Decker as deputy chief of staff, Colonel George S. Price as assistant chief of staff, G-1 (Personnel), Colonel Horton V. White as assistant chief of staff, G-2 (intelligence), Clyde Eddleman as assistant chief of staff, G-3 (operations) and Colonel Kenneth Pierce as assistant chief of staff, G-4 (supply).[38]

Honnen had health problems, and spent much of April, May and June 1943 in hospital before being ordered home on 18 June. He was replaced by Brigadier General Edwin D. Patrick, who had served on the staff of Admiral William F. Halsey in the South Pacific Area. Patrick did not get along smoothly with Krueger or the rest of the Sixth Army staff, and in May 1944 Patrick was appointed to command the 158th Regimental Combat Team, and Decker became chief of staff.[39][40]

Command in the Southwest Pacific Area was complicated. Instead of operations being conducted by the Sixth Army, its headquarters was used for what became Alamo Force. As a task force, Alamo Force came directly under MacArthur, rather than under the Allied Land Forces.[41] Krueger noted that "the inherent difficulties faced by my dual headquarters in planning and administration were aggravated by the command setup, which was a novel one to say the least."[42] Because Alamo Force was a purely operational entity, administration was handled by the United States Army Forces in the Far East.[42] Although there was only one army staff, Alamo Force was in New Guinea while the main body of Sixth Army headquarters was in Brisbane until February 1944, when the two were finally brought together. They still had a dual role as Alamo Force and Sixth Army until September, when Alamo Force was discontinued and the Sixth Army became directly responsible for operations.[43]

Bismarck Archipelago

The geographical, engineering and logistical difficulties of conducting operations in SWPA were driven home by Alamo Force's first operation, Operation Chronicle, the occupation of Woodlark and Kiriwina Islands in June 1943. Despite the fact that the operation was unopposed by the Japanese, it was subject to delays. Krueger visited Kiriwina, where road work and airbase development were held up by heavy rains, on 11 July. He was dissatisfied with the rate of progress and relieved the task force commander. The arrival of additional engineers sped up the base development effort, and No. 79 Squadron RAAF commenced operations from Kiriwina on 18 August.[44]

He was also concerned by reports of the invasion of Kiska in the Aleutian Islands in August 1943, in which a large Allied force invaded an island that had already been evacuated by the Japanese. If this could happen, it was also possible that a force might attack where the Japanese were unexpectedly strong. Different levels of command sometimes came up with widely varying estimates of Japanese strength because they used different methods to estimate it.[45]

An attempt to obtain information for Operation Dexterity, the attack on New Britain, with a joint Army-Navy reconnaissance team raised issues of inter-service cooperation. The Navy was mainly interested in gathering hydrographic data rather than information on the state of the Japanese defenders. Because of a breakdown in communications, the PT boat that was supposed to collect the team was unable to rendezvous with it, and the team had to spend eleven more days on the island. Finally, the Navy tried to prevent the Army commander from briefing Alamo Force headquarters on what had occurred.[45]

Krueger decided that he needed to have his own strategic reconnaissance capability. In November 1943, he formed the Alamo Scouts as a special unit for reconnaissance and raiding. An Alamo Scouts Training Center for volunteers was established on Fergusson Island, not far from Alamo Force's headquarters on Goodenough Island, under the command of Colonel Frederick W. Bradshaw, whom Krueger had first encountered during the Louisiana maneuvers. The top graduates of the six-week training course were assigned to the Alamo Scouts; the other graduates were returned to their units where they could be used for similar work. By the end of the war, Alamo Scouts teams had conducted 106 missions.[45][46]

In what became a standard procedure in SWPA, MacArthur's General Headquarters (GHQ) nominated the objectives, set the target date, and allocated the troops to the operation, leaving Alamo Force to work out the details. MacArthur was not inflexible, however, and allowed Krueger to alter the staging areas, and postpone the operation by a month. Krueger's concerns about the possibility of high casualties in securing the Gasmata area, and doubts as to whether the area was suitable for airbase development, led to it being dropped as a target. Arawe was substituted, and the size of the whole operation was scaled back.[47] Krueger hoped to observe the 1st Marine Division's landing at Cape Gloucester in December 1943, but was unable to do so until the planning for the January 1944 landing at Saidor was complete. He crossed the Dampier Strait in a PT boat in stormy weather. PBY Catalinas sent to bring him back were unable to land, and he had to return on the destroyer USS Mullany.[48]

Krueger accepted reports of a Japanese counterattack at Saidor, and sent reinforcements in response, but the attack did not eventuate. Because the 32nd Infantry Division was required for the upcoming Hansa Bay operation, he was initially reluctant to authorize it to block the trails behind the American beachhead. When he finally did so, it was too late. The retreating Japanese made good their escape, thereby defeating the whole purpose of the operation.[49][50] The next operation, the Admiralty Islands campaign in February 1944, played out differently. Based on Fifth Air Force reports that the islands were unoccupied, MacArthur accelerated his timetable and ordered an immediate reconnaissance in force of the islands. Krueger sent in the Alamo Scouts, who confirmed that the islands were still well-defended.[51]

Krueger did what he could to accelerate the movement of units of Major General Innis P. Swift's 1st Cavalry Division to the Admiralty Islands in response to urgent pleas from Brigadier General William C. Chase, who managed to defeat the numerically superior Japanese forces. Krueger was unimpressed with Chase. "His task", Krueger wrote to Swift, "was undoubtedly a difficult one, but did not, in my judgment, warrant the nervousness apparent in some of his despatches. This, and his failure to obey repeated positive orders to furnish detailed information of his situation and his losses, his closing his radio station during long periods, and his evident ignorance that reinforcements could not reach him by the times he demanded, were not calculated to inspire confidence."[52]

New Guinea Campaign

Over the next few months, the tempo of operations increased, forcing the Sixth Army to plan and execute multiple operations simultaneously.[53] Operations Reckless and Persecution in April 1944 together comprised the largest operation yet in SWPA, with the 24th and 41st Infantry Divisions of Lieutenant General Robert L. Eichelberger's I Corps landing at Tanahmerah and Humboldt bays near Hollandia, while the 163rd Regimental Combat Team landed at Aitape.[54] Eichelberger was Krueger's most senior subordinate, but when he did not meet Krueger's expectation, Krueger let him know in no uncertain terms. "In my more than 40 years as an officer", Krueger told one of his staff, "I have never raised my voice to an enlisted man, but a corps commander should know better."[55]

Krueger visited the beachhead with MacArthur and Eichelberger on the first day. After inspecting the beachhead, they went to the USS Nashville for ice cream sodas, whereupon MacArthur suggested, in view of the victory at Hollandia, they could accelerate the campaign timetable by moving on to Wakde-Sarmi immediately. Krueger was willing to consider the idea, although he had already ordered the troops designated for Wakde-Sarmi, the 32nd Infantry Division, to reinforce the position at Aitape, where he expected a major Japanese counterattack. Eichelberger was vehemently opposed, and the matter was dropped.[54][56]

Krueger moved his headquarters to Hollandia in May 1944. The swampy area with its restricted anchorages proved unsuitable for a major airbase complex, although fighter strips were constructed, and it was developed as a staging area.[57] MacArthur was compelled to press on with the Wakde-Sarmi project lest his troops become stranded without adequate air cover. A shortage of shipping meant that the operation had to be carried out by the troops in the Hollandia area, so Krueger nominated the 163rd Regimental Combat Team for Wakde, while the rest of the 41st Infantry Division captured Sarmi. However, with only days to go, doubts surfaced about the viability of construction in the Sarmi area, and Biak was substituted. In view of the difficulties involved in changing plans, and moving the troops around, MacArthur agreed to postpone both operations, Wakde until 17 May and Biak to 27 May.[58]

As a result, Alamo Force became involved in desperate fighting on three different fronts simultaneously. The landing at Wakde was opposed by nearly twice as many Japanese troops than had been expected.[59] When Krueger discovered that the Japanese were massing for an assault on the American position, he ordered a pre-emptive attack. "Krueger", wrote Edward Drea, "was too good a soldier to stand pat and wait for a Japanese attack."[60] Official historian Robert Ross Smith noted that "This decision, based upon the scanty, incomplete information concerning Japanese strength and dispositions available to General Krueger at the time, was destined to precipitate a protracted and bitter fight."[61] However, even if Krueger had known the true size of the Japanese force, he might still, under the circumstances, have taken the same approach.[62]

The estimates of the number of Japanese troops on Biak were out by a similar margin, resulting in heavy casualties. In the Battle of Biak, stubborn Japanese resistance halted the 41st Infantry Division, and forced its commander, Major General Horace H. Fuller, to appeal to Krueger for reinforcements. In response, Krueger sent the 163rd Regimental Combat Team from Wakde.[63] MacArthur soon grew impatient, as he needed the airstrips on Biak to support Admiral Chester Nimitz's Invasion of Saipan. Nimitz's operation ultimately drew Japanese attention away from Biak.[64]

MacArthur put pressure on Krueger for results, and Krueger in turn put pressure on Fuller. Krueger decided that Fuller had too many responsibilities as both task force commander and division commander, and decided to supersede him by sending Eichelberger to take over the task force. Fuller then submitted his resignation. Eichelberger's chief of staff, Brigadier General Clovis Byers, offered to have Decker intercept and destroy the resignation before Krueger saw it, but Fuller decided against this. The battle raged for nearly a month. Afterwards, Krueger demanded an explanation from Eichelberger as to why he had allowed Fuller to quit.[65]

Meanwhile, Japanese forces under Lieutenant General Hatazō Adachi attacked Alamo Force's position at Aitape in the Battle of Driniumor River. Krueger called for an energetic defense, but the cautious commander of XI Corps, Major General Charles P. Hall, retained nine battalions around the airbase at Tadji. This left Brigadier General Clarence A. Martin without the resources to implement Krueger's strategy, and he conducted a fighting withdrawal instead. Krueger travelled to Aitape where Hall presented him a counterattack plan, which he approved. By August, the fighting had ended and Adachi had been defeated.[66]

Philippines Campaign

MacArthur accelerated his timetable yet again in September 1944, and brought forward the planned invasion of Leyte to October 1944.[67] That this was the worst time of the year for campaigning on Leyte was not overlooked.[68] Typhoons and heavy rains hampered the efforts to construct and rehabilitate airbases, and without them, large numbers of aircraft could not operate from Leyte. This meant not only that few air strikes could be flown in support of the Sixth Army, but that the Allied Air Forces could not prevent the Japanese from reinforcing Leyte.[69]

An additional five Japanese divisions and two mixed brigades were sent to Leyte, and the battle became one of grinding attrition.[70] Able to view his troops in action more often than hitherto, Krueger found much to criticize. He noted that tanks were employed poorly, that the infantry were not aggressive enough, and saw poor sanitation and meals as a sign that officers were not taking adequate care of their men.[71] Krueger's generalship has also been questioned, with Ronald Spector criticizing "Krueger's disastrous decision to delay the push into the mountains west of Carigara in favor of beach defense."[72] Krueger based his cautious appreciation of the situation on various intelligence sources rather than relying solely on Ultra.[73]

In January 1945, the Sixth Army embarked on its largest, longest and last campaign, the invasion of Luzon. Krueger intended to make "maximum utilization of America's materiel and industrial superiority".[74] Once again, intelligence estimates of Japanese strength were questionable. MacArthur's intelligence officer, Brigadier General Charles A. Willoughby, basing his estimates on Ultra, believed that there were about 172,000 Japanese troops on Luzon. Krueger's intelligence officer, Colonel Horton V. White, reckoned that there were 234,000.[75]

MacArthur did not believe there were anywhere near that number. In fact, General Tomoyuki Yamashita had 287,000 troops on Luzon.[75] For the first time since Louisiana in 1941, Krueger was able to maneuver his army as a single body instead of having elements employed on multiple battles on scattered islands.[76] He regarded Yamashita's employment of armor as poor. Instead of using the 2nd Armored Division for a decisive counterattack against the vulnerable flank, Yamashita frittered away its strength in piecemeal efforts.[77]

As the campaign unfolded, Krueger was pressured by MacArthur to capture Manila. He sent messages reporting what he saw as a lack of drive among the troops, and even moved his theater headquarters forward of Krueger's. MacArthur tried to exploit Krueger's rivalry with Eichelberger by allowing the latter's Eighth Army to conduct its own drive on Manila from the south.[78] Krueger eventually sent a flying column from the 1st Cavalry Division, but MacArthur's expectation that the Japanese would not defend Manila was proven incorrect.[79] Weeks of ferocious fighting were required to capture the city.[80]

Krueger was promoted to general on 5 March 1945.[81] MacArthur recommended Krueger for the rank, even as he clashed with him over the drive on Manila, and rated Krueger's generalship higher than that of Patton or Omar Bradley.[81] Krueger's campaign on Luzon continued until 30 June 1945, when he handed over responsibility to Eichelberger in order to prepare for Operation Olympic, the invasion of Kyushu.[82]

This proved unnecessary when Japan surrendered, and in September 1945 the Sixth Army took up occupation duty in Japan. Krueger established his headquarters in Kyoto, and assumed responsibility for Kyushu, Shikoku and southern Honshu.[83] The Sixth Army remained in Japan until it handed over its occupation responsibilities to the Eighth Army on 31 December 1945. It was deactivated on 25 January 1946,[84] and Krueger retired in July.[85] For his service as commander of the Sixth Army in World War II, Krueger was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, an oak leaf cluster to his Distinguished Service Medal, and the Navy Distinguished Service Medal. He was awarded a second oak leaf cluster to his Distinguished Service Medal for his part in the Occupation of Japan.[86]

Later life

Krueger retired to San Antonio, Texas, where, in February 1946, he bought a house for the first time. Because of a large income tax bill left over from the war, he was unable to buy it outright and so some of his friends established the Krueger Fund Committee, which paid for much of the house. In retirement, Krueger was involved in a number of charity and community organizations, including the United Service Organization, the Red Cross, and the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, and he served as director of civil defense for San Antonio and Bexar County.[87]

Colonel Horton White, Krueger's former intelligence officer, approached him with an offer from George Edward Brett of Macmillan to publish his memoirs. Krueger did not wish to write an autobiography, which he felt was "invariably apt to be an apologia",[88] but was willing to write up an account of the Sixth Army's exploits. He commenced work in 1947, but the project proceeded slowly. The result was From Down Under to Nippon: The Story of the 6th Army In World War II, which was published in 1953. Historians were disappointed with the book, as it recounted what was known from the Sixth Army's reports, but provided little insight into the reasons why operations were conducted the way they were.[89]

Krueger kept in contact with his wartime colleagues. He was proud of the subsequent accomplishments of members of his wartime staff, and traveled to New York each year to celebrate MacArthur's birthday with MacArthur and other former senior commanders of the Southwest Pacific Area. He lectured at Army Schools and civic organizations, offering opinions on subjects such as the value of training, the benefit of universal military service, and the need for a unified defense establishment.[89]

Kinsella v. Krueger

Krueger's retirement was marred by family tragedies. His son James was dismissed from the army in 1947 for conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman after a drunken incident. Grace's health deteriorated, and she suffered from heart disease and high blood pressure. She was diagnosed with cancer in 1955, and died on 13 May 1956.[90] Most dramatically, on 3 October 1952, a lonely and depressed Dorothy fatally stabbed her husband, Colonel Aubrey D. Smith, with a hunting knife while he slept in their Army quarters in Japan. Dorothy, who felt that her husband now regarded her no more than "a clinging handicap to his professional career",[91] had turned to alcohol and drugs.[91]

By six votes to three, a U.S. Army court-martial found Dorothy guilty of first-degree murder and sentenced her "to be confined at hard labor for the rest of her natural life".[91] A unanimous verdict of guilty would have made the death sentence mandatory.[91] She was flown back to the United States in a Military Air Transport Service plane and was imprisoned at the Federal Prison Camp, Alderson, in West Virginia. The United States Court of Military Appeals rejected an appeal filed by Krueger's lawyers that argued that Dorothy was not sane at the time of the incident, and that the testimony that the court-martial had heard to the contrary was military rather than medical.[92]

However, in 1955, in a similar case involving another woman, Clarice B. Covert, who had killed her husband in England with an axe, Federal District Court Judge Edward A. Tamm ruled that civilians who accompany military forces overseas could not be imprisoned by military courts.[93] The two cases, Kinsella v. Krueger and Reid v. Covert, went to the U.S. Supreme Court, which affirmed that military trials of civilians were indeed constitutional,[94] only to reverse itself a year later in a review of the decisions.[95] Dorothy was released, and went to live with Krueger in San Antonio.[96]

When his old friend Fay Babson wrote a letter in 1960 complaining about not being promoted before retirement, Krueger replied that:

I wish you would compare your situation with mine for a moment. You are fortunate in having a loving wife by your side and three wonderful children. I, on the other hand, have lost my precious wife, my son Jimmie's career ended in disgrace and my only daughter's tragic action broke my heart. All the promotions and honors that have come to me cannot possibly outweigh these heartaches and disappointments. If true happiness is the aim of life—and I believe it is—then you are more fortunate than I and I would gladly trade with you.[97]

Death and legacy

Krueger's health began to decline in the late 1950s. He developed glaucoma in his right eye, and sciatica in his left hip. In 1960, he had a hernia operation, followed by kidney surgery in 1963. Nonetheless, he continued to attend MacArthur's birthday in New York. He died from pneumonia at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, on 20 August 1967,[97] and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.[98] His papers are in the Cushing Memorial Library at Texas A&M University.[99]

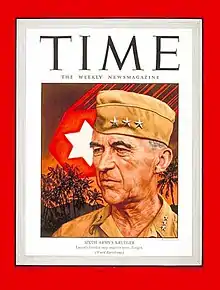

Although Krueger led a large force in operations over a large area for over two years, appearing on the cover of Time magazine on 29 January 1945,[5] and Krueger Middle School was named after him in San Antonio, Texas, in 1962,[100] he never became a well-known figure like MacArthur. Krueger's forte was what is today termed the operational level of war, transforming MacArthur's strategic vision into reality.[101] Krueger has usually been characterised as "an overly cautious commander who impeded MacArthur's fast-paced strategy."[101] William Manchester speculated that "the General knew his plodding subordinate was a useful counterweight to his own bravura",[102] and Edward Drea noted that at the Battle of the Drinumor, Krueger's actions were "entirely out of keeping with his otherwise methodical and plodding generalship".[103] MacArthur wrote:

History has not given him due credit for his greatness. I do not believe that the annals of American history have shown his superior as an Army commander. Swift and sure in the attack, tenacious and determined in defense, modest and restrained in victory—I do not know what he would have been in defeat, because he was never defeated.[104]

Dates of rank

| No pin insignia in 1898 | Enlisted, 2nd U.S. Volunteer Infantry: 17 June 1898 |

| No pin insignia in 1898 | Enlisted, 12th Infantry: 1 June 1899 |

| No pin insignia in 1901 | Second lieutenant, United States Army: 2 February 1901 |

| First lieutenant, United States Army: 10 October 1905 | |

| Captain, United States Army: 17 June 1916 | |

|

Lieutenant colonel, National Guard: 10 July 1916 |

| Captain, United States Army: 27 October 1916 | |

|

Major, National Army: 5 August 1917 |

|

Lieutenant colonel, Temporary: 13 June 1918 |

|

Colonel, Regular Army: 6 May 1919 |

|

Major, Regular Army: 1 July 1920 |

|

Lieutenant colonel, Regular Army: 27 April 1921 |

|

Colonel, Regular Army: 1 August 1932 |

| Brigadier general, Regular Army: 1 May 1936 | |

| Major general, Regular Army: 1 February 1939 | |

| Lieutenant general, Army of the United States: 16 May 1941 | |

| Major general, Retired List: 31 January 1945 (Retained on active duty.) | |

| General, Army of the United States: 5 March 1945 | |

| General, Retired List: 20 July 1946 | |

Notes

- Holzimmer 2007, pp. 10–11.

- "Historia ratusza" (in Polish). Zlotowskie.pl. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- Holzimmer 2007, p. 11.

- Collins 1983, p. 15.

- "Old Soldier". Time. 29 January 1945. Archived from the original on 12 March 2008.

- Holzimmer 2007, p. 12.

- Holzimmer 2007, pp. 15–16.

- Holzimmer 2007, pp. 16, 18, 20.

- Holzimmer 2007, p. 236.

- Holzimmer 2007, pp. 18–20.

- Holzimmer 2007, pp. 18–23.

- MacDonald 1989, p. 17.

- Holzimmer 2007, pp. 24–25.

- "Brief History of the 110th Infantry". Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- Holzimmer 2007, pp. 24–26.

- Holzimmer 2007, pp. 26–29.

- Holzimmer 2007, pp. 29–35.

- Holzimmer 2007, pp. 36–39.

- Holzimmer 2007, p. 42.

- MacDonald 1989, p. 23.

- Holzimmer 2007, pp. 46–47.

- Holzimmer 2007, p. 49.

- Holzimmer 2007, p. 51.

- Holzimmer 2007, pp. 52–55.

- Holzimmer 2007, p. 63.

- Gabel 1992, p. 67.

- Holzimmer 2007, p. 66.

- Holzimmer 2007, pp. 69–70.

- Holzimmer 2007, pp. 73–76.

- Krueger 1953, p. 4.

- Gabel 1992, pp. 64–67.

- Gabel 1992, pp. 96–99.

- Gabel 1992, p. 103.

- Holzimmer 2007, p. 97.

- Krueger 1953, p. 3.

- Holzimmer 2007, p. 102.

- Krueger 1953, pp. 3–6.

- Krueger 1953, pp. 3–6, 375–376.

- Holzimmer 2007, p. 127.

- Krueger 1953, p. 24.

- Krueger 1953, p. 10.

- Krueger 1953, p. 76.

- Krueger 1953, pp. 29, 76.

- Miller 1959, pp. 58–59.

- Holzimmer 2007, pp. 110–115.

- Krueger 1953, p. 29.

- Holzimmer 2007, pp. 116–116.

- Krueger 1953, pp. 34–35.

- Krueger 1953, pp. 36–38.

- Dexter 1961, p. 732.

- Krueger 1953, pp. 45–49.

- Holzimmer 2007, p. 140.

- Krueger 1953, p. 95.

- Taafe 1998, pp. 82–83.

- Taafe 1998, p. 100.

- Holzimmer 2007, pp. 144–147.

- Taafe 1998, p. 99, 102.

- Taafe 1998, pp. 122–123.

- Drea 1992, pp. 134–135.

- Drea 1992, pp. 133.

- Smith 1953, p. 238.

- Taafe 1998, pp. 142–143.

- Holzimmer 2007, p. 157.

- Taafe 1998, p. 156.

- Taafe 1998, pp. 165–169.

- Holzimmer 2007, pp. 171–175.

- Krueger 1953, p. 143.

- Holzimmer 2007, p. 187.

- Krueger 1953, pp. 193–195.

- Holzimmer 2007, p. 194.

- Holzimmer 2007, pp. 204–205.

- Spector 1985, p. 514.

- Holzimmer 1995, pp. 662–663.

- Holzimmer 2007, p. 210.

- Drea 1992, pp. 181–187.

- Holzimmer 2007, p. 212.

- Krueger 1953, pp. 256–257.

- Holzimmer 2007, pp. 216–219.

- Krueger 1953, pp. 243–245.

- Krueger 1953, pp. 246–252.

- Holzimmer 2007, p. 224.

- Holzimmer 2007, pp. 227–228.

- Holzimmer 2007, pp. 235–236.

- Krueger 1953, p. 369.

- Ancell & Miller 1996, pp. 178–170.

- "Valor Awards for Walter Krueger". Military Times. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- Holzimmer 2007, p. 242.

- Holzimmer 2007, p. 243.

- Holzimmer 2007, pp. 242–248.

- Holzimmer 2007, p. 249.

- "Neurotic Explosion". Time. 19 January 1953.

- Wiener 1988, pp. 6–7.

- "We Want Them Accountable". Time. 5 December 1955. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007.

- "Kinsella v. Krueger, 351 U.S. 470 (1956)". US Supreme Court. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- "Reid v. Covert, 354 U.S. 1 (1957)". US Supreme Court. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- Holzimmer 2007, p. 250.

- Holzimmer 2007, p. 251.

- Burial Detail: Krueger, Walter (Section 90, 794) – at ANC Explorer

- "Inventory of the General Walter Krueger Papers: 1943–1945". Texas A&M University. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- "Walter Krueger Middle School". North East Independent School District. Archived from the original on 17 October 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- Holzimmer 2007, p. 252.

- Manchester 1978, p. 410.

- Drea 1984, p. 138.

- MacArthur 1964, p. 170.

- Official Register of Commissioned Officers of the United States Army. 1948. Vol. II. p. 2291.

References

- Ancell, R. Manning; Miller, Christine (1996). The Biographical Dictionary of World War II Generals and Flag Officers: The US Armed Forces. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-29546-8.

- Collins, Arthur S. Jr. (January–February 1983). "Walter Krueger: An Infantry Great". Infantry. 73 (1): 14–19. ISSN 0019-9532. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Dexter, David (1961). The New Guinea Offensives. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 1 – Army. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 2028994. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2008. Retrieved 16 December 2006.

- Drea, Edward J. (1984). Defending the Driniumor: Covering Force Operations in New Guinea, 1944. Leavenworth papers, No. 9. Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Combat Studies Institute, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College. OCLC 11327410.

- Drea, Edward J. (1992). MacArthur's Ultra: Codebreaking and the War Against Japan 1942–1945. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0504-5. OCLC 23651196.

- Gabel, Christopher R. (1992). The U.S. Army GHQ Maneuvers of 1941. Washington, DC: Center of Military History, U.S. Army. ISBN 0-16-061295-0. OCLC 71320615.

- Holzimmer, Kevin C. (October 1995). "Walter Krueger, Douglas MacArthur, and the Pacific War: The Wakde-Sarmi Campaign as a Case Study". The Journal of Military History. Society for Military History. 59 (4): 661–686. doi:10.2307/2944497. ISSN 1543-7795. JSTOR 2944497.

- Holzimmer, Kevin C. (2007). General Walter Krueger: Unsung Hero of the Pacific War. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1500-1.

- Krueger, Walter (1953). From Down Under to Nippon: The Story of the 6th Army In World War II. Lawrence: Zenger Pub. ISBN 0-89201-046-0.

- MacArthur, Douglas (1964). Reminiscences of General of the Army Douglas MacArthur. Annapolis: Bluejacket Books. ISBN 1-55750-483-0. OCLC 220661276.

- MacDonald, John H. (1989). General Walter Krueger: A Case Study on Operational Command. Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: U.S. Army Command and General Staff College. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 April 2013. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- Manchester, William (1978). American Caesar: Douglas MacArthur 1880–1964. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 0-440-30424-5. OCLC 3844481.

- Miller, John, Jr (1959). The War in the Pacific: Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul. Washington, DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army. OCLC 1355535.

- Smith, Robert Ross (1953). The Approach to the Philippines (PDF). United States Army in World War II: The War in the Pacific. Washington, DC: United States Army Center of Military History. OCLC 1260896. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2012. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- Spector, Ronald H. (1985). Eagle Against the Sun: The American War with Japan. New York: Free Press. ISBN 0-02-930360-5. OCLC 10998802.

- Taafe, Stephen R. (1998). MacArthur's Jungle War: The 1944 New Guinea Campaign. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0870-2. OCLC 37107216.

- Wiener, Frederick Bernays (Summer 1988). "Persuading the Supreme Court to Reverse Itself: Reid v. Covert". Litigation. 14 (4): 6–10. JSTOR 29759264.

Further reading

- Taaffe, Stephen R. Marshall and His Generals: U.S. Army Commanders in World War II (2011) excerpt

- "Aubrey Dewitt Smith, Colonel, United States Army". ArlingtonCemetery.net. An unofficial website.