William Matthews (priest)

William Matthews (December 16, 1770 – April 30, 1854), occasionally spelled Mathews,[lower-alpha 1] was an American who became the fifth Roman Catholic priest ordained in the United States and the first such person born in British America. Born in the colonial Province of Maryland, he was briefly a novice in the Society of Jesus. After being ordained, he became influential in establishing Catholic parochial and educational institutions in Washington, D.C. He was the second pastor of St. Patrick's Church, serving for most of his life. He served as the sixth president of Georgetown College, later known as Georgetown University. Matthews acted as president of the Washington Catholic Seminary, which became Gonzaga College High School, and oversaw the continuity of the school during suppression by the church and financial insecurity.

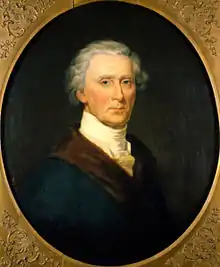

The Very Reverend William Matthews | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Engraving of William Matthews by George Parker | |

| 7th President of Georgetown College | |

| In office February 28, 1809 – November 1, 1809 | |

| Preceded by | Francis Neale |

| Succeeded by | Francis Neale |

| Personal details | |

| Born | December 16, 1770 Port Tobacco, Maryland Colony, British America |

| Died | April 30, 1854 (aged 83) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Mount Olivet Cemetery |

| Relations | Ann Teresa Mathews (sister) |

| Alma mater |

|

| Political party | Federalist Party, Whig Party |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | March 29, 1800 by John Carroll |

Matthews was vicar apostolic and apostolic administrator of the Diocese of Philadelphia during a period of ecclesiastical turmoil. He was a co-founder and president of the Washington Library Company for thirteen years—the first public library in the District of Columbia. He also was co-director and trustee of the District of Columbia Public Schools, where he was one of the superintendents of a school. He played a significant role in the founding of Washington Visitation Academy for girls, St. Peter's Church on Capitol Hill, and the parish that now includes the Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle.

Matthews was involved in Catholic charitable organizations as well; he was the founder and president of St. Vincent's Female Orphan Asylum and the co-founder and president of St. Joseph's Male Orphan Asylum.

He was born into a prominent Maryland family and became a close adviser to Archbishop John Carroll, the first Catholic bishop in the United States. He became well connected with the capital's political elite, and was chosen to preside over the first Catholic ceremony in the White House, and the only Catholic wedding in its history. He believed that because Catholics enjoyed the freedom to practice their religion in the United States under the Constitution, they had a duty to contribute to the "moral and physical good" of their communities. He staunchly opposed slavery. For his contributions to religious and civic life, Matthews was informally known as the "patriarch of Washington."

Early life

William Matthews was born on December 16, 1770 in the small village of Port Tobacco in Charles County in the Maryland Colony of British America to a prominent, established Maryland family.[3] He was the son of William Matthews, Sr. and Mary Neale.[4] The youngest of seven children,[5] his siblings were Joseph, Ignatius, Mary, Susanna, Margaret, and Ann Teresa.[6] His father, with whom he had little interaction, died when he was six years old. William Matthews Sr.'s ancestry traces to the English landed gentry, and includes Thomas Matthews—an early settler of the Maryland colony who was granted 4,000 acres (1,600 ha) of land in Port Tobacco, Maryland, by the Lords Calvert. His mother descended from Captain James Neale, who settled in the Maryland colony in the mid-seventeenth century. Matthews' matrilineal ancestry traces its origins to the noble O'Neills of Ireland.[4] His cousin, Charles Carroll of Carrollton, was the sole Catholic signatory of the Declaration of Independence.

In 1781, aged eleven, Matthews witnessed British troops burn part of his family's estate during the American Revolution.[7] From his parents, Matthews received a sizable inheritance that he drew from throughout his life for the advancement of the church.[8] Two of his nephews on his mother's side became politicians: US Senator Richard T. Merrick and Judge William Matthews Merrick.[9] Matthews became the brother-in-law of Senator William Duhurst Merrick.[10]

Many of Matthews' matrilineal relatives entered the priesthood. Six of his mother's seven brothers became Jesuits, and one died during the Jesuit novitiate. His uncle, Bennett Neale, was one of the first Jesuits in the English colony. His other maternal uncles were: Francis Neale, who both preceded and succeeded him as president of Georgetown College; Leonard Neale, the Archbishop of Baltimore and also president of Georgetown; and Charles Neale, the superior of the Jesuits in America.[4]

His paternal aunt, Ann Mathews,[lower-alpha 1] became a Discalced Carmelite nun in Hoogstraet, in what is now Belgium, taking the name Sister Bernardina Teresa Xavier of St. Joseph. Two of his sisters—Susanna (Sister Mary Eleanora) and Ann Teresa (Sister Mary Aloysia)—also went to Hoogstraet to become Carmelite nuns.[1] In 1790 Sister Bernardina returned to what was now the United States and established a Carmelite convent in the village of Port Tobacco, Maryland, where she had been given land for this purpose. Her nieces also returned to Maryland with her.[11]

Education

At the age of twelve Matthews was sent to Liège in the Prince-Bishopric of Liège (modern-day Belgium)[12] to be educated at the College of St Omer, an English Jesuit school.[13] He studied classics as one of the last Americans to be sent to the English school at Liége.[8]

He returned to America in his early twenties to briefly study theology at Georgetown College. While at Georgetown in 1796, he was chosen to be the first student to greet President George Washington upon his visit to the college.[14] He entered St. Mary's Seminary in Baltimore in 1797.[15] While still a student there, Matthews frequently served as an instructor of English at Georgetown College because the professors and seminarians at St. Mary's were asked by Bishop John Carroll to assist with the teaching duties of the Jesuits at Georgetown.[16] The adult Matthews was described as "short, stocky, [and] dark-haired", with a prominent Aquiline nose.[17]

Priesthood

Returning to his alma mater, Matthews was appointed a professor of rhetoric at Georgetown in 1796, where his lectures were described as monotonous.[18] On December 23, 1798, he took his minor orders. He was strongly attracted to the Jesuits, likely influenced by his uncle Ignatius Matthews' membership in the society.[9] Matthews became a subdeacon on August 22, 1799 and was ordained as a transitional deacon on March 26, 1800.[19] Matthews was ordained a priest at St. Peter's Church in Baltimore,[lower-alpha 2] on March 29, 1800 by Bishop John Carroll.[2][18] With his ordination, he became the fifth Catholic priest ordained in the United States and the first such person born in British America.[19][22] Later, he served as a missionary in southern Maryland and occasionally as a teacher at Georgetown.[18]

St. Patrick's Church

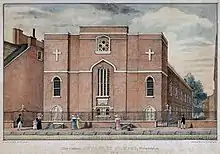

.jpg.webp)

Matthews became the second pastor of St. Patrick's Church, succeeding the Dominican priest Anthony Caffry.[23] St. Patrick's was the largest parish in the District of Columbia at the time[24] and the first Catholic church to be constructed in the City of Washington.[25][lower-alpha 3] Matthews held the post from 1804 until his death.[19][28] He self-financed the purchase of eight lots near St. Patrick's, believing the location would become the heart of the growing city. Three further Catholic parishes, three schools, and an orphanage were established on the land.[29] Matthews oversaw construction of a new, larger church in 1809 on the site of the original building.[30] The brick, Gothic Revival church was completed in 1816.[8] This new St. Patrick's was consecrated by Archbishop John Carroll, and the mass was concelebrated by Leonard Neale.[14]

During the War of 1812, British troops invaded Washington, D.C., in 1814. Matthews barricaded himself and others inside the sanctuary of St. Patrick's Church while most of the city's population fled. As the troops advanced to within two blocks of St. Patrick's, fire from surrounding buildings spread to the roof of the church. Matthews went to the roof to put out the fire,[31] then persuaded General Robert Ross not to destroy the church.[32]

During his tenure as pastor, Matthews fostered an unusually large number of conversions to Catholicism. Among his parishioners were Chief Justice Roger Taney, Pierre L'Enfant, James Hoban, Mayor Robert Brent, and Mayor Thomas Carbery.[33] His parish produced a great many seminarians for the priesthood and novices to become nuns. He performed baptisms for a considerable number of black freedmen and slaves. He was said to have "detested slavery,"[34] and on at least one occasion, he purchased a mother and her child at a slave auction to grant them freedom. Matthews purchased a pipe organ for St. Patrick's from an Episcopal church in Dumfries, Virginia—likely the first organ in the District of Columbia.[35] He acted as trusted adviser to Bishop John Carroll, whose ecclesiastical jurisdiction as Bishop of Baltimore and later as Archbishop of Baltimore, included the City of Washington[lower-alpha 4] and served as a liaison between the bishop and Catholic institutions and priests in Washington. Matthews was also involved in raising money for St. Mary's Seminary in Baltimore by selling lottery tickets to parishioners.[37] From 1827 to 1830, Charles Constantine Pise was Matthews' assistant at St. Patrick's.[38] Another one of his assistants was Gabriel Richard.[31]

St. Peter's Church

In 1820, Archbishop Carroll tasked Matthews with establishing the second Catholic parish in Washington: St. Peter's Church. While construction started on a church building, the project quickly ran out of money and went into debt. Matthews ensured that the project was completed. He decided a new site should be chosen and secured a donation of land on Capitol Hill by Daniel Carroll.[39] The church was eventually completed in 1821.[40]

He opposed the control of St. Peter's Church properties by lay trustees, as the issue of trusteeism was still active in American Catholic Church.[41] This opposition motivated his subsequent selection for an ecclesiastical mission in Philadelphia.[40]

In 1821, the Propaganda Fide in Rome removed Norfolk, Virginia from the jurisdiction of the Archdiocese of Baltimore, placing it within the new Diocese of Richmond.[42] This upset Matthews, who arranged for Archbishop Ambrose Maréchal of Baltimore to use the diplomatic pouch of the French ambassador to the United States to express his misgivings; the ambassador would deliver the archbishop's letters to French ministers to the Holy See, who would present the communications. This would have provided some weightiness to Maréchal's petitions, but it is unclear if he made use of this arrangement.[43]

Recovery of Ann Mattingly

One of Matthews' parishioners, Ann Mattingly, suffered from a tumor in her breast for at least six years. She was in poor health; several doctors and numerous other witnesses had attested to Mattingly's advanced and worsening illness and their inability to treat the disease with the medicine of the time. By 1824, her physicians and attending priests, including Matthews, expected her imminent death.[44] Matthews, along with Stephen Dubuisson and Anthony Kohlmann, turned to the German priest and reputed miracle worker Prince Hohenlohe who prescribed a novena for his cures to be effective; he also set aside the tenth day of each month for offering Mass for the sick outside Europe. Following nine days of public prayer at St. Patrick's parish,[45] on the night of March 9, 1824, Matthews visited Mattingly at 10 pm to hear her confession. The following morning, she received communion during a Mass said by Dubuisson at 4 am. It was then reported to Matthews that she was instantly restored to health and that large ulcers on her back vanished. Matthews immediately went to visit her; according to him, she was smiling and greeted him at the door. Mattingly's quick recovery was noted by several prominent Washington physicians, and by those attending to her in bed, as shocking.[44]

When word of the event circulated, it was sensationalized by the local press. Matthews responded by criticizing the priests who exaggerated the story, but described the event to the National Intelligencer as a miracle.[44] He compiled A Collection of Affidavits and Certificates Relative to the Wonderful Cure of Mrs. Ann Mattingly, Which Took Place in the City of Washington, D.C., on the Tenth of March, 1824.[46] By way of Anthony Kohlmann, this pamphlet made its way to Pope Leo XII, who had it translated into Italian and published by his personal printer.[47]

Academic career

Georgetown College

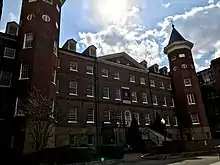

By 1806, Matthews had become vice president of Georgetown College, and by 1808, he had become a member of its board of directors,[48] where he served until 1815.[49] He was elected president on February 28, 1809, succeeding his uncle Francis Neale. On the same day that he became president, Matthews entered the Jesuit novitiate, which was highly atypical for someone of his age and position.[19] Although working at the college, Matthews chose not to live there and instead moved into St. Patrick's Church.[48]

Soon after his election, Matthews became disillusioned with the Society of Jesus and quit the Jesuits on November 1, 1809, resigning the presidency of the Jesuit-run Georgetown at the same time.[24] His uncle, Francis Neale, once again resumed the presidency of Georgetown.[19] The Jesuits had been wary of accepting Matthews' full membership because he had been a member of the Corporation of Roman Catholic Clergymen of Maryland, which considered itself a continuation of the Jesuits in America during the suppression of the Society of Jesus. After the society was restored, there was friction between the Jesuits and the enduring Corporation.[50][lower-alpha 5] Matthews' relationship with Anthony Kohlmann, a subsequent president of Georgetown, was particularly difficult.[48]

Two of Matthews' pupils were Charles Boarman—the son of one of the college's professors, who left Georgetown College to join the Navy—and William Wilson Corcoran, who became the first president of Georgetown's alumni association in 1881. Under Matthews' presidency, the towers of Old North Hall were finally completed.[19]

Washington Seminary

As St. Patrick's parish grew, Matthews sought to obtain several assistant curates. At the same time, Georgetown College sought to move its seminarians to a location removed from "worldly distractions", and several within the Society of Jesus wanted to turn St. Patrick's into a Jesuit parish. Consequently, on June 13, 1815, despite his earlier disagreements with the society, Matthews offered the Jesuits a plot of land adjacent to the church on which to build a house of Jesuit priests who would assist him in his parochial duties and simultaneously accommodate the relocated Jesuit seminarians. While the Jesuits prepared to move into the new building, they allowed George Ironside, an educator and former Episcopal priest who converted to Catholicism,[52] to use the structure as a school for lay students beginning in 1817. Subsequently, Anthony Kohlmann returned to Washington and continued operation of the school as its superior. This gave rise to the Washington Catholic Seminary (a school primarily for lay students, not seminarians) on September 8, 1821, contrary to the initial intentions of Matthews—who sought to build a rectory—and the Jesuits, who sought to use the building as their seminary.[53] Since this arrangement did not provide Matthews with the assistant priests he initially sought, he wrote to Archbishop Maréchal expressing his desire that the Jesuits, who he viewed as trying to take over his parish, be removed from the land of St. Patrick's.[54]

Nonetheless, Matthews succeeded Adam Marshall as third president of Washington Catholic Seminary—later Gonzaga College High School—in 1824.[24] He also taught as a faculty member at the school.[55] He served as a figurehead president so that the school could accept tuition; Jesuits were forbidden from accepting tuition, but Matthews was permitted to do so because he was a secular priest no longer affiliated with the society.[24] This arrangement allowed the school to prosper. From the start of his presidency until 1827, Matthews worked with Jeremiah Keiley, who was a Jesuit; Matthews oversaw the finances and admissions of the school, while Keiley, as the superior of the Jesuit house, oversaw the curriculum. When word of the arrangement reached the Jesuit Superior General in Rome, Luigi Fortis, he ordered that the Seminary be suppressed on September 25, 1827. Matthews, without success, repeatedly petitioned the Superior General to permit the continuation of the school.[55]

Upon the seminary's suppression, Keiley left the Society of Jesus and founded a new, short-lived school. Matthews remained and oversaw the school that was now officially closed but still operating despite the order.[56] He remained president until 1848 when the Jesuits, now permitted to accept tuition, resumed control of the school. After Matthews, John E. Blox became president.[24] Upon the resumption of Jesuit administration, the school was renamed Washington College and again as Gonzaga College in 1857.[57]

Civic life

Washington Library

In 1811, Matthews co-founded the District of Columbia's first permanent public library, the Washington Library Association,[58] which secured its congressional charter as the Washington Library Company on April 18, 1814, preceding the District of Columbia Public Library. Along with 200 other benefactors, Matthews contributed money by purchasing substantial stock in the library. He served on several of the library's committees, which were responsible for drafting its rules and purchasing books.[59] He was elected the library's second president on April 18, 1821, succeeding the pastor of the F Street Presbyterian Church, Dr. James Laurie.[60] The library prospered under Matthews, where it was used by employees of the federal government and private citizens. He led a successful campaign to raise money by selling library stock, which was invested in Washington's banks and real estate.[61]

In the spring of 1827, he purchased a Masonic lodge on Eleventh Street as the first permanent home for the library.[59] Throughout his presidency, its collections steadily increased in size. Matthews acquired 3,000 volumes of Peter Force's collection on American history,[58] doubling the Washington Library's holdings; doing so required a personal loan from him. His presidency came to an end in April 1834[60] when he was succeeded by Samuel Harrison Smith and Peter Force.[62]

Washington Public Schools

Matthews was a trustee of the District of Columbia Public Schools from July 13, 1813 to 1844. For a part of his term, he served as co-director of the school system, and as one of three members of the board of trustees who collectively acted as superintendents of the Lancasterian school—one of three schools of the public school system alongside the Eastern and Western schools.[63] In this capacity, he visited the school quarterly, and oversaw instruction of the students and performance of the teachers.[64]

The school system was perpetually underfunded by the Washington City Council; as a result, the less resource-intensive Lancasterian system was instituted and the school suffered insufficient facilities for many years. It was periodically taken over by the District of Columbia Militia for training, which disrupted studies.[65] On several occasions, the board of trustees requested that Matthews obtain the funds from the City Council that were statutorily promised to them; he separately solicited private donations as well. Matthews further acted as a member of a committee charged with persuading President James Madison to sell his stable on Fourteenth and G Streets to be used as the new schoolhouse for the Lancasterian school. He sat on another committee that was charged with making rules and regulations for the school system in 1815, and the reorganization of the system in 1816.[66]

St. Vincent's Orphan Asylum

In 1825, Matthews founded the St. Vincent's Female Orphan Asylum near St. Patrick's Church in Washington.[67] He had requested that several nuns of the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul in Emitsburg go to Washington to care for the orphaned girls of the city.[68][lower-alpha 6] Matthews gave $400 and a small, white house on F Street to the three sisters who came to found the orphanage. During Matthews' time as its president, the institution was run by the nuns. Funding for the institution came initially from parishioners of St. Patrick's; the parish would hold fundraising events for the asylum, which became the center of parish life. This allowed it to expand to a larger facility on 10th and G Streets in 1828.[69] In 1832, Matthews persuaded Congress to equally divide between St. Vincent's and the Washington Orphan Asylum a plot of land that was valued at $20,000.[70]

The orphanage was incorporated by an act of Congress, which also remitted some of its taxes until Congress exempted it from property taxes entirely. Matthews' friendships with many of Washington's social elite drew contributions to the orphanage from people such as Mayor Thomas Carberry and President Andrew Jackson. He was also well acquainted with Daniel Webster, Henry Clay, and Roger Taney. These friendships were partly the result of Matthews' strong Federalist and later Whig views.[71]

The initial purpose of the institution was to be an orphanage for girls, but since its founding, it was operated as a free school for poor children of Washington that educated orphans and non-orphans alike. This educational function became integral to the institution's purpose, and the number of non-orphaned students eventually far exceeded the number of orphans. In 1831, a board of trustees and a board of female lay managers were created, the latter of which was composed of prominent women in the District who were able to enlist financial support for the institution. On May 14, 1849, to accommodate the institution's growth, the cornerstone for a new building was laid at the same site. Matthews served as president of the asylum from its founding to his death in 1854.[69]

Visitation Academy

Eventually, a female counterpart to the Washington Seminary was established as the Washington Visitation Academy. Its purpose was to educate girls of a higher social class than those at St. Vincent's, as education in Washington was socioeconomically divided at the time. By 1850, a school for girls at Ninth and F Streets, on land that was owned by St. Patrick's Church, prospered. The school was initially run by the Daughters of Charity, but the rules of their order eventually required them to leave the school. It was then taken over by the Sisters of the Visitation from the Georgetown Visitation Convent, who sought to create a school similar to the Georgetown Visitation Academy.[70] At a time when it was considered improper to educate girls in higher academic subjects, but rather only in how to behave in polite society, the Visitation Academy sought to educate girls in both skills.[67]

Matthews was not involved in the direct management of the institution but provided financial support. The school moved into a mansion originally intended as the French ambassador's residence, but it was unable to pay the $3,000 mortgage. The superior, Mother Juliana, requested assistance from him.[lower-alpha 6] Matthews declined, as he had previously offered them land and a building free of charge. Several days later, however, he contributed $10,000 to support the school.[67]

St. Joseph's Orphan Asylum

In mid-1853, the board of trustees of St. Vincent's Asylum approved the creation of St. Joseph's Male Orphan Asylum, later renamed the St. Joseph's Home and School for Boys. Matthews had attempted to create a male orphanage in October 1843, but this closed by 1846. He and Timothy O'Toole, his successor as pastor of St. Patrick's Church,[35] oversaw the establishment of the new orphanage, and Matthews served as president of its board from its founding.[69] Matthews died before its opening in February 1855. His will bequeathed $3,000 to the boys' orphanage that, like St. Vincent's, relied on private donations and government assistance for funding.[72]

Vicar Apostolic of Philadelphia

On February 26, 1828, the Prefect of the Propaganda Fide, Cardinal Mauro Cappellari, instructed Archbishop Ambrose Maréchal of Baltimore to effectuate the appointment of Matthews by Pope Leo XII as vicar apostolic and apostolic administrator of the Diocese of Philadelphia.[73][74] This order was promulgated because Bishop Henry Conwell of Philadelphia had been recalled to Rome by the Holy See due to a long-brewing schism over lay trusteeism, and Maréchal had been ordered to oversee the diocese during his absence.[75][76] Alongside his appointment as administrator, Matthews was also appointed by Bishop Conwell as senior pastor and superior of the clergy at St. Mary's Cathedral,[77][78] which was one of the centers of the trustee dispute.[79] When Bishop Conwell attempted to return to his diocese from Rome against the orders of the Propaganda Fide during their investigation, the congregation empowered Matthews to announce Conwell's suspension from episcopal office.[80]

As apostolic administrator, Matthews took part in the First Provincial Council of Baltimore and acted as a theologian for the participating bishops.[81] He also acted as a representative of the Diocese of Philadelphia at the council, in place of Bishop Conwell.[82] He was later appointed the coadjutor of the Diocese of Philadelphia, which would have elevated him to the episcopate, with the expectation that he would eventually become Bishop of Philadelphia, but he declined the position and the elevation.[19] Instead, Matthews expressed his desire to step down as vicar apostolic,[83] and his term came to an end in 1829.[74] In his place, Francis Kenrick was appointed coadjutor bishop in 1830.[80] At one point, Matthews also declined being appointed the coadjutor bishop of the Diocese of Richmond.[14]

Return to Washington

Matthews had a strong spiritual commitment, and he was especially fond of the devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, encouraging it in his parish and in churches in Baltimore. For this reason, he was chosen by the Visitation Sisters as their spiritual director in 1831.[84][85] The following year, Matthews officiated at the wedding of Mary Anne Lewis—a ward of President Andrew Jackson and a Catholic—and Joseph Pageot, the secretary of the French diplomatic legation to the United States. The wedding took place on November 29, 1832 in the East Room of the White House,[86][87] and signified the first Catholic ceremony in the history of the White House,[88] and the only Catholic wedding in its history.[89] One year later, Matthews again presided over a ceremony in the White House, this time in the Red Room,[86] with the baptism of Lewis and Pageot's only son, Andrew Jackson Pageot.[88] This baptism marked the second Catholic ceremony in the residence's history.[90] Matthews believed that since Catholics were granted the freedom to practice their religion by the Constitution of the United States, they had a duty to contribute to the "moral and physical good" of their communities.[34]

In the 1830s, Matthews sold his house to fund the building of a new church on the northeastern corner of 15th and H Streets near the White House to alleviate overcrowding at St. Patrick's Church.[91] A new parish was founded in 1839 and the new church was completed in 1840; it was dedicated on November 1 that year.[92] The church was named St. Matthew's Church in honor of both Saint Matthew and William Matthews.[91] The building was replaced by the Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle as the parish's church in the 1890s.[93]

Death and legacy

Matthews died on April 30, 1854 and was buried in the cemetery adjacent to St. Patrick's Church. In the mid-1870s, to allow for construction of a new church, his body was exhumed along with the rest of those in the cemetery. While being transferred to a new coffin, it was observed that the body was remarkably preserved.[94][lower-alpha 7] The corpse was laid in front of the altar, where it remained during the All Souls' Day Mass, before being reinterred in the priests' section[96] of Mount Olivet Cemetery.[35][97] It was reported that at his death, he requested that he be "laid upon the floor to expire" because he "did not deserve to die in his chair". During the latter part of his life and after his death, Matthews was nicknamed the "patriarch of Washington" due to his contributions to the religious and civic worlds of the city.[28][22] On his gravestone in Mount Olivet Cemetery, the Serra Club placed a bronze plaque in 1973, commemorating his life.[34]

In his will, he bequeathed monies to St. Vincent's Asylum, enabling the construction of a larger school on G Street in 1857. The school endured through the nineteenth century, playing a major role in educating girls in Washington.[69]

In the center of a mural by Edwin Blashfield above the doors of St. Matthew's Cathedral in Washington,[98] Matthews is depicted alongside other important figures of the early Catholic church in America; he stands beside Archbishop Michael Curley and Cardinal James Gibbons.[99] Matthews is also depicted in the interior frieze of the Cathedral of Mary Our Queen in Baltimore. The relief depicts his ordination, where he is shown kneeling with his head bowed as Bishop John Carroll places his hands on Matthews' head.[100]

Notes

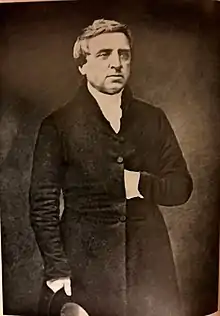

_(full).jpg.webp)

- The Matthews surname is spelled in some contemporaneous sources as "Mathews".[1][2]

- Matthews was ordained in St. Peter's because the church was serving as pro-cathedral for the Diocese of Baltimore.[20][21]

- While Holy Trinity Church had actually been founded earlier, it was incorporated in Georgetown by the State of Maryland, not the District of Columbia. The City of Washington was not merged with Georgetown to form a unified government for the District of Columbia until the Organic Act of 1871.[26] Therefore, St. Patrick's was the first Catholic church in the City of Washington.[27]

- The Archdiocese of Washington had not yet been erected.[36]

- The Corporation of Roman Catholic Clergymen of Maryland was incorporated as a civil entity by the Maryland General Assembly in 1792 in response to the suppression of the Society of Jesus in 1773 by Pope Clement XIV. Its purpose was to preserve the property of the former Jesuits with the hope that the Society would be one day restored and the property returned under the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of the Jesuit superior in America. The Jesuits did not want their property to be seized by the state, by the Propaganda Fide (which had exercised jurisdiction over the United States as a mission church since 1776), or by the bishop (whom the Holy See had ordered to take possession of all Jesuit property as part of its suppression). When the Society of Jesus began to be restored in America in 1805 by allowing former Maryland Jesuits to join the Russian Jesuit province, the Corporation endured and expanded for some time, causing friction among those who renewed their Jesuit vows and those who did not. Indeed, even when Pope Pius VII officially restored the Society of Jesus worldwide in 1815, the Corporation continued to add new members, some of whom had never been Jesuits before the suppression. With the Corporation's endurance continued its legal possession of the former Jesuit property, instead of the return of the property to the now-restored Jesuit order.[50][51]

- The local superior of the Daughters of Charity, Mother Juliana, was Matthews' niece.[67]

- Bodies that are preserved by means other than deliberate or accidental embalming are known as incorrupt bodies and are regarded as significant in Catholicism and much of Christianity. Incorruptibility is associated with (but is not on its own indicative of) sainthood.[95]

References

Citations

- Currier 1989, p. 51.

- de Courcy 1857, p. 552.

- Durkin 1963, p. 3.

- Durkin 1963, p. 4.

- Donnelly 1982, p. 45

- Newman 2007, p. 247

- Durkin 1963, p. 6.

- Warner 1994, p. 102.

- Shea 1891, pp. 36–37.

- McLaughlin 1899, p. 75.

- Guilday, Peter (1922). The Life and Times of John Carroll: Archbishop of Baltimore, 1735-1815 (Public domain ed.). Encyclopedia Press. pp. 487ff. Retrieved August 1, 2019.

- "History of Liège". Eupedia. Archived from the original on August 6, 2017. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

- Whitehead 2016, Conclusion.

- Hinkel 1957, p. 36.

- Whitehead 2016, p. 215.

- Durkin 1963, p. 10.

- Durkin 1963, p. 9.

- Durkin 1963, p. 11.

- Curran 1993, pp. 62–63.

- Spalding 1989, pp. 22, 30–31.

- "St. Peter's Pro-Cathedral". Archdiocese of Baltimore. Archived from the original on July 1, 2017.

- Kerney 1856, p. 289.

- MacGregor 1994, p. 20.

- Buckley 2013, p. 101.

- MacGregor 1994, p. 18.

- Dodd 1909, p. 4.

- Durkin 1963, pp. 11–12.

- Liston, Paul. "A Short History of St. Patrick Parish". St. Patrick Catholic Church. Archived from the original on August 1, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2018.

- Durkin 1963, p. 14.

- Frye 1920, p. 35.

- Hinkel 1957, p. 37.

- Durkin 1963, pp. 16–17.

- Metz 1912, p. 559.

- Donnelly 1990, p. 66

- Catholic Editing Company 1914, p. 117.

- "Timeline for Archdiocese of Washington". Catholic Standard. Archdiocese of Washington. September 24, 2014. Archived from the original on August 31, 2018. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- Durkin 1963, pp. 130–131.

- Thorp 1978, p. 28.

- Durkin 1963, pp. 138–140.

- Durkin 1963, pp. 138–142.

- "History". St. Peter's on Capitol Hill. Archived from the original on April 7, 2017. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- "History of the Diocese". Catholic Diocese of Richmond. Archived from the original on August 13, 2018. Retrieved August 31, 2018.

- Durkin 1963, p. 143.

- Durkin 1963, pp. 132–137.

- Schultz 2011, pp. 10–11.

- Matthews 1824, p. 3.

- Curran 1987, p. 52.

- Durkin 1963, pp. 14–16.

- Curran 1993, p. 402.

- Curran 2012, pp. 14–16.

- Schroth 2017, pp. 59–64.

- Curran 1993, p. 93.

- Durkin 1963, pp. 83–86.

- Warner 1994, p. 106

- Hill 1922, Chapter III.

- Durkin 1963, p. 100.

- Warner 1994, p. 107.

- Haley 1861, p. 213.

- Durkin 1963, p. 29.

- Johnston 1904, p. 25.

- Durkin 1963, p. 27.

- Durkin 1963, p. 24.

- Crew 1892, p. 487.

- Durkin 1963, pp. 57, 60–61.

- Durkin 1963, p. 63.

- Durkin 1963, pp. 64, 67–68.

- Durkin 1963, pp. 119–122.

- Downing 1917, p. 743.

- "An Inventory of Catholic Charities of the Archdiocese of Washington, DC". American Catholic History Research Center and University Archives. Catholic Charities of the Archdiocese of Washington. Archived from the original on December 3, 2017. Retrieved February 25, 2018 – via Catholic University of America Library.

- Warner 1994, p. 104.

- Durkin 1963, p. 22.

- Durkin 1963, pp. 117–118.

- Ennis 1976, pp. 103–104.

- American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia 1909, p. 251.

- Loughlin 1913, pp. 349–350.

- Ennis 1976, p. 103.

- Shea 1890, p. 258.

- Griffin 1917, p. 331

- "A Brief History of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia". Archdiocese of Philadelphia. Archived from the original on November 11, 2016. Retrieved July 8, 2018.

- Ennis 1976, p. 104.

- Casey 1957, pp. 43–44.

- Griffin 1917, p. 346

- Clarke 1890, p. 4.

- Durkin 1963, p. 128.

- Lathrop & Lathrop 1894, p. 377.

- Stickley 1965, p. 192.

- "Wedding Ceremonies Held at the White House". White House Historical Association. Archived from the original on November 30, 2018. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- Korson, Gerald (July 23, 2006). "Catholics in the White House". Our Sunday Visitor. Archived from the original on September 16, 2018. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- "White House Brides and Envisioned Flowers". White House Historical Association. Archived from the original on February 12, 2019. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- Craughwell, Thomas (September 16, 2016). "Unexpected American Catholics". National Catholic Register. Archived from the original on September 17, 2016. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- Fogle 2005, p. 124.

- "St. Matthew's Cathedral". NRHP Travel Itinerary: Washington, D.C. National Park Service. Archived from the original on June 17, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2018.

- "About Us: Our History". Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle. February 19, 2010. Archived from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2018.

- Diaz, Kevin (March 31, 2000). "God Is in the Real Estate". Washington City Paper. Archived from the original on April 19, 2018. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- Cruz 1991, Introduction.

- Hinkel 1957, p. 39

- MacGregor 1994, p. 190.

- "Tour: Exterior & Design". Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle. February 27, 2010. Archived from the original on February 26, 2017. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

- "About Us: Baptistry and Nave". Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle. March 2010. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2018.

- Durkin 1963, p. 56.

Sources

- American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia (September 1909). "Letters from the Archepiscopal Archives at Baltimore: 1790–1814". Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia. 20 (3): 250–289. JSTOR 44208046. OCLC 1479632.

- Buckley, Cornelius Michael (2013). Stephen Larigaudelle Dubuisson, S.J. (1786–1864) and the Reform of the American Jesuits. Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America. ISBN 978-0761862321. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- Casey, Thomas Francis (1957). The Sacred Congregation de Propaganda Fide and the Revision of the First Provincial Council of Baltimore (1829–1830). Rome: Gregorian Biblical BookShop. ISBN 978-8876520662. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved March 15, 2018 – via Google Books.

- Catholic Editing Company (1914). The Catholic Church in the United States of America: Undertaken to Celebrate the Golden Jubilee of His Holiness, Pope Pius X. New York: Catholic Editing Company. p. 117. OCLC 976946591. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- Clarke, Richard Henry (1890). "Province of Philadelphia". History of the Catholic Church in the United States from the Earliest Period to the Present Time. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: Gebbie & Company. pp. 1–26. OCLC 971006131. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- Crew, Harvey W. (1892). "Educational History". Centennial History of the City of Washington, D.C. Dayton, OH: United Brethren Publishing House. pp. 489–518. OCLC 34571629. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- Cruz, Joan Carroll (1991). "Introduction". The Incorruptibles: A Study of Incorruption in the Bodies of Various Saints and Beati. Charlotte, NC: TAN Books. ISBN 978-0895559531. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- Curran, Robert Emmett (January 1987). ""The Finger of God Is Here": The Advent of the Miraculous in the Nineteenth-Century American Catholic Community". The Catholic Historical Review. 73 (1): 41–61. JSTOR 25022452.

- Curran, Robert Emmett (1993). The Bicentennial History of Georgetown University: From Academy to University (1789–1889). Vol. 1 (First ed.). Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. ISBN 978-0-87840-485-8. OCLC 794228400. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- Curran, Robert Emmett (2012). "Ambrose Maréchal, the Jesuits, and the Demise of Ecclesial Republicanism in Maryland, 1818–1838". Shaping American Catholicism: Maryland and New York, 1805–1915. Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press. pp. 13–158. ISBN 978-0813219677. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

- Currier, Charles Warren (1989). "Chapter V: The New World". Carmelite Sources: Carmel in America. Vol. 1 (Bicentennial ed.). Darien, IL: Carmelite Press. pp. 43–55. ISBN 978-0-9624104-0-6. Archived from the original on October 7, 2010.

- de Courcy, Henri (1857). "Appendix". The Catholic Church in the United States: Pages of Its History. Translated by Shea, James Gilmary (2 ed.). New York: Edward Dunigan. pp. 539–591. OCLC 6504685. Archived from the original on October 17, 2018. Retrieved October 16, 2018.

- Dodd, Walter Fairleigh (1909). The government of the District of Columbia. Washington, DC: John Byrne & Co. p. 4. OCLC 494007852. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018.

- Donnelly, Mary Louise (1982). Craycrofts of Maryland and Kentucky Kin. Burke, Virginia: M.L. Donnelly. ISBN 0-939142-06-6.

- Donnelly, Mary Louise (1990). Major William Boarman, Charles County, Maryland (1630–1709): His Descendants, Boarman/Bowman and Allied Families. Ennis, Texas: M.L. Donnelly. ISBN 0-939142-11-2.

- Downing, Margaret B. (1917). "Catholic Founders of the National Capital". New Catholic World. Vol. 105. New York: Paulist Fathers. pp. 732–743. OCLC 39329168. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- Durkin, Joseph Thomas (1963). William Matthews: Priest and Citizen. New York: Benziger Brothers. LCCN 64001710. OCLC 558792300.

- Ennis, Arthur J. (1976). "Chapter Two: The New Diocese". In Connelly, James F. (ed.). The History of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia. Wynnewood, Pennsylvania: Unigraphics Incorporated. pp. 63–112. LCCN 78105474. OCLC 4192313.

- Fogle, Jeanne (2005). Washington, D.C.: A Pictorial Celebration, Part 3. New York: Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. p. 124. ISBN 978-1402715273. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

william matthews washington dc.

- Frye, Virginia King (1920). "St. Patrick's: First Catholic Church of the Federal City". Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. 23: 26–51. JSTOR 40067137.

- Griffin, Martin I.J. (December 1917). "The Life of Bishop Conwell". Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia. 28 (4): 310–347. JSTOR 44208445.

- Haley, William D'Arcy, ed. (1861). "Chapter VIII: City of Washington". Philp's Washington Described: A Complete View of the American Capital, and the District of Columbia, with Many Notices, Historical, Topographical, and Scientific, of the Seat of Government. New York: Rudd & Carleton. pp. 203–221. OCLC 54223220. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- Hill, Owen Aloysius (1922). "Chapter III: Rev. Jeremiah Keiley, S.J. (1826–1827)". Gonzaga College, an Historical Sketch: From Its Foundation in 1821, to the Solemn Celebration of Its First Centenary in 1921. Washington, DC: Gonzaga College. pp. 33–39. OCLC 1266588. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved March 15, 2018 – via Google Books.

- Hinkel, John V. (1957). "St. Patrick's: Mother Church of Washington". Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. 57/59: 33–43. JSTOR 40067183.

- Johnston, W. Dawson (1904). "Early History of the Washington Library Company and Other Local Libraries". Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. 7: 20–38. JSTOR 40066838.

- Kerney, Martin Joseph (1856). The Metropolitan: A Monthly Magazine, Devoted to Religion, Education, Literature, and General Information. Vol. 4. Baltimore: John Murphy & Company. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- Lathrop, George Parsons; Lathrop, Rose Hawthorne (1894). A Story of Courage: Annals of the Georgetown Convent of the Visitation of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Cambridge, MA: Riverside Press. OCLC 5218883. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved September 9, 2018.

- Loughlin, James F. (1913). "Henry Conwell". In Herbermann, Charles G.; Pace, Edward A.; Pallen, Condé B.; Shahan, Thomas J.; Wynne, John J. (eds.). The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 4. New York: Universal Knowledge Foundation. pp. 349–350. Archived from the original on October 21, 2018. Retrieved October 20, 2018.

- MacGregor, Morris J. (1994). A Parish for the Federal City: St. Patrick's in Washington, 1794–1994. Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press. ISBN 978-0-8132-0801-5. OCLC 29636010. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- Matthews, William (1824). A Collection of Affidavits and Certificates, Relative to the Wonderful Cure of Mrs. Ann Mattingly: Which Took Place in the City of Washington, D.C., on the Tenth of March, 1824. Washington, DC: James Wilson. OCLC 32860442. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- McLaughlin, James Fairfax (1899). College Days at Georgetown: And Other Papers. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company. p. 75. OCLC 1299424. Retrieved October 20, 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- Metz, William J. (1912). "Washington, District of Columbia". In Herbermann, Charles G.; Pace, Edward A.; Pallen, Condé B.; Shahan, Thomas J.; Wynne, John J. (eds.). The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 15. New York: Robert Appleton Company. pp. 558–564. OCLC 1017058. Archived from the original on October 21, 2018. Retrieved October 20, 2018.

- Newman, Harry Wright (2007). The Maryland Semmes and Kindred Families. Westminster, MD: Heritage Books. ISBN 978-0-7884-2308-6. Archived from the original on March 3, 2019. Retrieved March 3, 2019 – via Google Books.

- Schroth, Raymond A. (Spring 2017). "Death and Resurrection: The Suppression of the Jesuits in North America". American Catholic Studies. 128 (1): 51–66. doi:10.1353/acs.2017.0014. ISSN 2161-8534.

- Schultz, Nancy Lusignan (2011). Mrs. Mattingly's Miracle: The Prince, The Widow, and the Cure That Shocked Washington City. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0300171709. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- Shea, John Gilmary (1890). A History of the Catholic Church Within the Limits of the United States, from the First Attempted Colonization to the Present Time: From the division of the Diocese of Baltimore, 1808, and death of Archbishop Carroll, 1815, to the Fifth Provincial Council of Baltimore, 1843. John Gilmary Shea. OCLC 28996263. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved September 8, 2018 – via Google Books.

- Shea, John Gilmary (1891). Memorial of the First Century of Georgetown College, D.C.: Comprising a History of Georgetown University, Part 3. New York: P.F. Collier. p. 34. OCLC 612832863. Retrieved February 24, 2018.

william matthews georgetown.

- Spalding, Thomas W. (1989). The Premier See: A History of the Archdiocese of Baltimore, 1789–1989. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-3857-6.

- Stickley, Julia Ward (July 1965). "Catholic Ceremonies in the White House, 1832–1833: Andrew Jackson's Forgotten Ward, Mary Lewis". The Catholic Historical Review. 51 (2): 192–198. JSTOR 25017652.

- Thorp, Willard (1978). Catholic Novelists in Defense of Their Faith, 1829–1865 (PDF). The American Catholic Tradition (Reprint ed.). New York: Arno Press. pp. 25–117. ISBN 978-0-405-10862-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 8, 2016. Retrieved March 14, 2018 – via American Antiquarian Society.

- Warner, William W. (1994). "Part II: The Church". At Peace with All Their Neighbors: Catholics and Catholicism in the National Capital, 1787–1860. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. ISBN 978-1589012431. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- Whitehead, Maurice (2016). English Jesuit Education: Expulsion, Suppression, Survival, Restoration, 1762–1803. Farnham, England: Routledge. ISBN 978-1317143048. OCLC 820426724. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved July 4, 2018.

External links

- Works by or about William Matthews at Internet Archive

- Correspondence between Thomas Jefferson and, inter alia, William Matthews at the American Founding Era Collection of the University of Virginia Press

- William Matthews at Find a Grave