Willie McCovey

Willie Lee McCovey (January 10, 1938 – October 31, 2018), nicknamed "Stretch", "Mac" and "Willie Mac",[lower-alpha 1] was an American professional baseball player. He played in Major League Baseball as a first baseman from 1959 to 1980, most notably as a member of the San Francisco Giants for whom he played for 19 seasons. McCovey also played for the San Diego Padres and Oakland Athletics in the latter part of his MLB career.

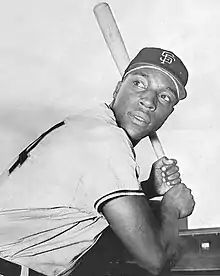

| Willie McCovey | |

|---|---|

McCovey in 1961 | |

| First baseman | |

| Born: January 10, 1938 Mobile, Alabama | |

| Died: October 31, 2018 (aged 80) Stanford, California | |

Batted: Left Threw: Left | |

| MLB debut | |

| July 30, 1959, for the San Francisco Giants | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| July 6, 1980, for the San Francisco Giants | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Batting average | .270 |

| Hits | 2,211 |

| Home runs | 521 |

| Runs batted in | 1,555 |

| Teams | |

| |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| Member of the National | |

| Induction | 1986 |

| Vote | 81.4% (first ballot) |

A fearsome left-handed power hitter, at the time of his retirement in 1980, McCovey ranked second only to Babe Ruth in career home runs among left-handed batters, and seventh overall. As of 2022, he ranks 20th overall on baseball's all-time home run list, tied with Ted Williams and Frank Thomas. He was a six-time All-Star, three-time home run champion, MVP, and was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1986 in his first year of eligibility, only the 16th man so honored, at the time.

McCovey was known as a dead-pull[2] line drive hitter, causing some teams to employ a shift against him.[3] McCovey was called "the scariest hitter in baseball" by pitcher Bob Gibson, seconded by similarly feared slugger Reggie Jackson.[4] McCovey hit 521 home runs, 231 of them in Candlestick Park, the most in that park by any player. A home run he hit on September 16, 1966, was described as the longest ever hit in that stadium.[5]

Early life

McCovey was born in Mobile, Alabama, the seventh child of ten born to Frank McCovey, a railroad worker, and Esther.[6] He began working part time at the age of 12 and dropped out of high school in order to work full time.[7]

Professional career

Minor Leagues

Despite being passed on by scout Ed Scott, who signed Hank Aaron for the Negro American League Indianapolis Clowns, McCovey was invited to a New York Giants tryout camp in Melbourne, Florida, while he was living and working in Los Angeles. The invitation came from Giants scout and former Negro league owner Alex Pompez.[7]

In 1955 McCovey made his professional debut. The Sandersville Giants of the Georgia State League in Sandersville, Georgia had McCovey on their roster, with McCovey having signed a contract for $175.00 per month. His signing bonus was a mere $500.[8] McCovey was 17 years old, 6'2", 165 pounds, and proceeded to hit .305 with 19 home runs, scoring 113 runs in 107 games.[9]

On his way to the Major Leagues, McCovey played for a San Francisco Giants' farm club in Dallas, Texas that was part of the Class AA Texas League. He did not participate when his team played in Shreveport, Louisiana due to segregation in that city. He later played for the Pacific Coast League Phoenix Giants just prior to being called up by the San Francisco Giants.[10]

San Francisco Giants (1959–1973)

In his Major League debut on July 30, 1959, McCovey went four-for-four against Hall-of-Famer Robin Roberts of the Philadelphia Phillies with two singles and two triples.[1] McCovey found major league pitchers simpler to hit than minor leaguers because the major leaguers had better control of their pitches.[1] In 52 major league games, he had a .354 batting average and 13 home runs. He was named the National League's (NL) Rookie of the Year.[6] He won the NL Player of the Month Award in August, his first full month in the majors (.373, 8 HR, 22 RBI). He had a 22-game hitting streak, setting the mark for San Francisco Giants rookies, four short of the all-time team record.[11]

The 1960 season was disappointing for McCovey. Season-long struggles caused him to be demoted to the minor leagues at one point, and the San Francisco fans booed him relentlessly. In nearly twice as many games as the previous year (101 to 52), he still hit the same number of home runs (13), batting .238.[12][13]

McCovey was not the only first baseman on the Giants. First base was also the natural position of Orlando Cepeda, who had won the NL Rookie of the Year Award the year before McCovey and played about 60 games at the position in 1959 when McCovey was in the minor leagues. However, new manager Alvin Dark declared McCovey his first baseman for 1961, putting Cepeda in right field to begin the year.[14] Dark also assigned Willie Mays as McCovey's roommate.[15]

In 1962, Dark decided to put Cepeda at first base full-time and move McCovey to the outfield. James S. Hirsch, who wrote a biography of Mays, reported that a recurring joke among the Giants "was that McCovey didn't need a glove to play the outfield, just a blindfold and a cigarette."[16] Because McCovey had struggled against left-handed pitching, Dark played him only when a right-hander was starting and frequently pinch-hit for McCovey if a left-hander was brought in.[7] Thus, McCovey played only 91 games, but he still hit 20 home runs.[16] He helped the Giants to the World Series against the New York Yankees,[17] the only World Series appearance of his career.[18] He hit a home run against Ralph Terry in Game 2, which the Giants won 2–0.[19] In the bottom of the ninth inning of Game 7, with two outs and the Giants trailing 1–0, Mays was on second base and Matty Alou was on third base. Any base hit would likely have won the championship for the Giants. McCovey hit a hard line drive that was snared by the Yankees' second baseman Bobby Richardson, ending the series with a Yankees' win.[17]

The moment was immortalized in two Peanuts comic strips by Charles M. Schulz.[6][20] The first ran on December 22, 1962, with Charlie Brown sitting silently alongside Linus for three panels before suddenly lamenting, "Why couldn't McCovey have hit the ball just three feet higher?" The second, from January 28, 1963, featured Charlie Brown breaking an identical extended silence by crying, "Or why couldn't McCovey have hit the ball even two feet higher?"[21] On the occasion of his Hall of Fame election 26 years later, McCovey was asked how he would like his career to be remembered. “As the guy who hit the ball over Bobby Richardson’s head in the seventh game,” replied McCovey.[22]

McCovey spent many years at the heart of the Giants' batting order, along with fellow Hall-of-Fame member Willie Mays. His best year statistically was 1969, when he hit 45 home runs, had 126 RBI and batted .320 to become the National League MVP. He was also named the Most Valuable Player of the 1969 All-Star Game after hitting two home runs to lead the National League team to a 9–3 victory over the American League.[23] He won NL Player of the Month awards in July 1963 (.310, 13 HR, 27 RBI) and August 1969 (.315, 8 HR, 22 RBI). In 1963 he and Hank Aaron tied for the NL lead with 44 home runs.[6]

In the early years of Candlestick Park, the Giants home stadium, the area behind right field was open except for three small bleacher sections. When McCovey came to bat, typically those bleachers would empty as the fans positioned themselves on the flat ground, hoping to catch a McCovey home run ball.[24]

Injuries limited McCovey to 105 games in 1971, but he reached the playoffs for the first time in nine years as the Giants won the NL West.[25] He was afflicted by injuries again in 1972, as he broke his arm early in the year in a collision at first base.[26]

San Diego Padres and Oakland Athletics (1974–1976)

He was traded along with Bernie Williams from the Giants to the San Diego Padres for Mike Caldwell on October 25, 1973. Troubled with arthritic knees for two seasons, the 35‐year‐old McCovey was critical of manager Charlie Fox for diminishing his starting first baseman role in favor of Gary Thomasson.[27] The Giants had been trading their higher-priced players and gave McCovey input into his destination.[7] McCovey played in 128 games in 1974 and 122 games in 1975. He hit 22 home runs in 1974 and 23 in 1975.[28]

In 1976, McCovey struggled, and lost the starting first base job to Mike Ivie. He batted .203 with seven home runs in 71 games. Near the end of the season, the Oakland Athletics purchased his contract from the Padres. He played in eleven games for them.[7][28]

San Francisco (1977–1980)

McCovey returned to the Giants in 1977 without a guaranteed contract, but he earned a position on the team.[7] With Hank Aaron and Frank Robinson having retired at the end of the 1976 season with 755 and 586 home runs respectively, McCovey began 1977 as the active home run leader with 465. That year, during a June 27 game against the Cincinnati Reds, he became the first player to hit two home runs in one inning twice in his career (the first was on April 12, 1973), a feat since accomplished by Andre Dawson, Jeff King, Alex Rodriguez, and Edwin Encarnación. One was a grand slam and he became the first National Leaguer to hit seventeen. At age 39, he had 28 home runs and 86 RBIs and was named the Comeback Player of the Year.[29]

On June 30, 1978, at Atlanta's Fulton County Stadium, McCovey hit his 500th home run, and two years later, on May 3, 1980, at Montreal's Olympic Stadium, McCovey hit his 521st and last home run, off Scott Sanderson of the Montreal Expos. This home run gave McCovey the distinction, along with Ted Williams (with whom he was tied in home runs), Rickey Henderson, and Omar Vizquel of homering in four different decades: the 1950s, '60s, '70s, and '80s. McCovey is one of only 29 players in baseball history to date to have appeared in Major League baseball games in four decades.[30]

In his 22-year career, McCovey batted .270, with 521 home runs and 1,555 RBIs, 1,229 runs scored, 2,211 hits, 353 doubles, 46 triples, 1,345 bases on balls, a .374 on-base percentage and a .515 slugging percentage. He also hit 18 grand slam home runs in his career, a National League record,[31] and was a six-time All-Star.[32]

Post-playing career

McCovey was a senior advisor with the Giants for 18 years. In this role, he visited the team during spring training and during the season, providing advice and other services.[33]

In September 2003, McCovey and a business partner opened McCovey's Restaurant, a baseball-themed sports bar and restaurant located in Walnut Creek, California. The restaurant closed in February 2015.[34]

Legacy

| |

| McCovey's number 44 was retired by the San Francisco Giants in 1980. |

McCovey was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1986 in his first year of eligibility — making him the 16th player so honored. He appeared on 346 of 425 ballots cast (81.4 percent).[32][35]

McCovey is best remembered for the ferocity of his line drive batting style. In his book Ball Four, pitcher Jim Bouton wrote about watching the slugger blast the ball in batting practice, while making "little whimpering animal sounds" in response to each of McCovey's raw power drives. Reds manager Sparky Anderson also had a healthy respect for the damage McCovey could do, saying "I walked Willie McCovey so many times, he could have walked to the moon on all those walks." Announcer Jack Buck thought a McCovey line-drive home run to centerfield was the hardest ball he had ever seen anyone hit.[36] McCovey's bat was so lethal in his prime he was intentionally walked an all-time record 45 times in 1969, shattering the previous record by a dozen. This remained the major league mark for 33 years until broken by fellow Giant Barry Bonds. The following year McCovey was intentionally walked 40 times. Once, speaking to the pitcher before a McCovey at-bat, Mets inimitable manager Casey Stengel joked, "Where do you want to pitch him, upper deck or lower deck?"

In 1999, McCovey was ranked 56th on the Sporting News list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players,[37] and was nominated as a finalist for the Major League Baseball All-Century Team. Two years later, the sport's most prominent sabermetric analyst, Bill James, ranked him 69th, and the 9th-best first baseman.[38] Since 1980, the Giants have awarded the Willie Mac Award to honor his spirit and leadership.

The inlet of San Francisco Bay beyond the right field fence of Oracle Park, historically known as China Basin, has been re-dubbed McCovey Cove in his honor. A statue of McCovey was erected across McCovey Cove from the park, and the land on which it stands named McCovey Point. On September 21, 1980, the Giants retired his uniform number 44, which he wore in honor of Hank Aaron, a fellow Mobile, Alabama native.[39][40]

McCovey was inducted to the Multi-Ethnic Sports Hall of Fame (formerly the Afro Sports Hall of Fame)[41] in Oakland, California on February 7, 2009.[42][43] The Willie McCovey field at Woodside Elementary School in Woodside, California was rededicated to him in 2013.[10][44]

Personal life

McCovey's first marriage, to Karen McCovey, produced a daughter. On August 1, 2018, he married longtime girlfriend Estela Bejar at AT&T Park.[45] He had a quiet personality.[46]

In 1996, McCovey and fellow baseball Hall of Famer Duke Snider pled guilty to federal tax fraud charges that they had failed to report about $70,000 in income from sports card shows and memorabilia sales from 1988 to 1990. McCovey was given two years of probation and fined $5,000.[47][48] He received a pardon from President Barack Obama on January 17, 2017.[49]

In his later years, McCovey dealt with several health issues, including atrial fibrillation and an infection in 2015 that nearly killed him. After his career ended he endured several knee surgeries, which left him in a wheelchair, and he was hospitalized several times.[50]

McCovey died at the age of 80 at Stanford University Medical Center on October 31, 2018, after battling "ongoing health issues". He had been hospitalized for an infection late the previous week.[18] His longtime friend and fellow Hall of Famer Joe Morgan was at his bedside.[32] A public memorial service for McCovey was held at AT&T Park on November 8, 2018.

See also

- List of Major League Baseball home run records

- 500 home run club

- Bay Area Sports Hall of Fame

- List of Major League Baseball career home run leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career hits leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs batted in leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career total bases leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual runs batted in leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual home run leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career strikeouts by batters leaders

- List of Major League Baseball players who played in four decades

- List of people pardoned or granted clemency by the president of the United States

Notes

- The "Stretch" nickname came from his 6 feet 4 inches (1.93 m) frame, which allowed him to stretch and catch balls hit towards first base.[1]

References

- Hirsch, p. 309

- "McCovey And Mays Gave Foes Of Giants 'The Willies'". Forbes. Retrieved November 2, 2018.

- "#TBT: The origins of the shift - SweetSpot". ESPN. July 23, 2015. Retrieved November 2, 2018.

- Gibson, Bob; Jackson, Reggie; Wheeler, Lonnie (September 22, 2009). "Sixty Feet, Six Inches: A Hall of Fame Pitcher & a Hall of Fame Hitter Talk about How the Game is Played". Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group – via Google Books.

- "Blowing out the candle". April 4, 1999. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- Goldstein, Richard (October 31, 2018). "Willie McCovey, 80, Dies; Was Hall of Fame Slugger With the Giants". The New York Times. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- Armour, Mark. "Willie McCovey". Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- Hirsch, p. 283

- "Willie McCovey – Society for American Baseball Research".

- Dickey, Glenn (January 30, 2005). "CATCHING UP WITH WILLIE MCCOVEY / Back in the swing of things / Giants great on mend after surgery". San Francisco Chronicle.

- Shea, John (July 30, 2010). "Streak ends". SFChronicle.com. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

- "Willie McCovey Stats". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved January 5, 2021.

- Hirsch, pp. 327-38

- Hirsch, pp. 295, 334

- Hirsch, p. 340

- Hirsch, p. 350

- Vecsey, George (January 10, 1986). "Sports Of The Times; McCovey's Toughest Opponent". The New York Times. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- Kroner, Steve; Shea, John (October 31, 2018). "Willie McCovey: Giants legend dead at 80". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

- Hirsch, p. 370

- "Willie McCovey". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- Whiting, Sam (March 25, 2012). "Willie McCovey recalls '62 Series — 50 years ago". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- Killion, Ann (November 3, 2018). "There was no finer Giant than Willie McCovey". San Francisco Chronicle.

- "1969 All-Star game box score". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- "Giants Hall of Famer Willie McCovey dies at 80 | MLB". Sporting News. October 26, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- Hirsch, p. 499

- Hirsch, p. 506

- "Padres Get McCovey," The New York Times, Friday, October 26, 1973. Retrieved November 28, 2020

- Lanek, Joe (October 25, 2015). "The Padres acquired Willie McCovey this day in 1973". Gaslamp Ball. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- Gonzales, Richard (October 31, 2018). "Hall Of Fame Slugger Willie McCovey Dies At Age 80". NPR. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- Paul Casella (March 8, 2015). "Which current MLB players could play in four decades?". Sports on Earth. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- "Giants Hall of Famer Willie McCovey dies at 80". Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- "Willie McCovey: Giants legend dead at 80". SFChronicle.com. November 1, 2018. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- "Willie McCovey – Senior Advisor | San Francisco Giants". Mlb.com. May 24, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- "Walnut Creek: McCovey's closing downtown, possibly moving to San Francisco – East Bay Times". Eastbaytimes.com. December 31, 2014. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- Durso, Joseph. "MCCOVEY ELECTED TO HALL OF FAME". Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- Hirsch, pp. 308-09

- "100 Greatest Baseball Players by The Sporting News : A Legendary List by Baseball Almanac". Baseball-almanac.com. Retrieved January 11, 2013.

- James, Bill, The New Bill James Historical Abstract, Simon & Schuster Free Press, 2001, pgs. 365, 435

- "Willie McCovey Stats — Baseball-Reference.com". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- "Hank Aaron Stadium". milb.com. Retrieved July 10, 2017.

- "About Us | Multi-Ethnic Sports Hall of Fame". March 19, 2016. Archived from the original on March 19, 2016. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- Adkins, Jan Batiste (2012). African Americans of San Francisco. Arcadia Publishing. p. 72. ISBN 9780738576190.

- "Baseball legend Willie McCovey dies at 80 – SFBay". sfbay.ca. November 2018. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- "almanacnews.com: "Woodside: Hall of Fame San Francisco Giant Willie McCovey dies" - Related news". Newstral.com. Retrieved November 2, 2018.

- KGO (August 2, 2018). "San Francisco Giants legend Willie McCovey marries longtime girlfriend at AT&T Park". abc7news.com. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- Hirsch, p. 308

- Sexton, Joe (July 21, 1995). "Tax Fraud: Two Baseball Legends Say It's So". The New York Times.

- Bryan Armen Graham (January 17, 2017). "Hall of Fame first baseman Willie McCovey pardoned by Obama". The Guardian. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- "President Obama pardons Willie McCovey for tax evasion". USA Today. January 17, 2017. Retrieved July 10, 2017.

- Shea, John (January 7, 2018). "Giants legend Willie McCovey at 80: 'Every day is a blessing'". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved November 4, 2018.

- Hirsch, James S. (2010). Willie Mays: The Life, the Legend. New York: Scribner. ISBN 978-1-4165-4790-7.

External links

- Willie McCovey at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Career statistics and player information from MLB, or ESPN, or Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs

- Willie McCovey at Find a Grave