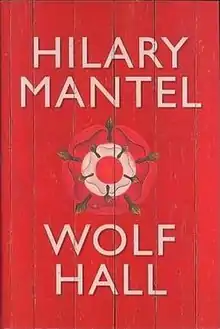

Wolf Hall

Wolf Hall is a 2009 historical novel by English author Hilary Mantel, published by Fourth Estate, named after the Seymour family's seat of Wolfhall, or Wulfhall, in Wiltshire. Set in the period from 1500 to 1535, Wolf Hall is a sympathetic fictionalised biography documenting the rapid rise to power of Thomas Cromwell in the court of Henry VIII through to the death of Sir Thomas More. The novel won both the Booker Prize and the National Book Critics Circle Award.[1][2] In 2012, The Observer named it as one of "The 10 best historical novels".[3]

| |

| Author | Hilary Mantel |

|---|---|

| Audio read by | Simon Slater |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Historical fiction |

| Publisher | Fourth Estate (UK) |

Publication date | 30 April 2009 |

| Media type | Print (hardback) |

| Pages | 672 |

| ISBN | 0-00-723018-4 |

| 823.92 | |

| LC Class | PR6063.A438 W65 2009 |

| Followed by | Bring Up the Bodies |

The book is the first in a trilogy; the sequel Bring Up the Bodies was published in 2012.[4] The last book in the trilogy is The Mirror and the Light (2020), which covers the last four years of Cromwell's life.[5]

Summary

In 1500, Thomas Cromwell, a young boy roughly 15 years of age, runs away from home because his abusive father nearly beats him to death. He decides to seek his fortune in France as a soldier.

By 1527 the well-travelled Cromwell has returned to England and is now a lawyer, a married father of three, and is highly respected as the right-hand man of Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, with a stellar reputation for deal-making. His life takes a tragic turn when his wife and two youngest daughters abruptly die of the sweating sickness, leaving him a widower.

The two men are together in 1529 when the Cardinal falls out of favour with King Henry VIII due to his inability to negotiate an annulment between the king and his wife Catherine of Aragon. Cromwell manages to buy the Cardinal a little time before everything the Cardinal owns is repossessed and given to Henry's mistress, Anne Boleyn. Cromwell subsequently decides to relocate the Cardinal and his entourage to a second home in Esher.

Though he knows the Cardinal is doomed, Cromwell begins negotiations on his behalf with the king. During the course of his visits he meets the recently widowed Mary Boleyn, Anne's older sister, and is intrigued by her. Cromwell is eventually summoned to meet Anne and finds Henry's loyalty to her unfathomable.

Continuing to gain favour with both the king and Anne, Cromwell is shocked when he learns, a year after the event, that the Cardinal had been recalled to London to face treason charges and died on the way. Cromwell mourns his death. Despite his known loyalty to Wolsey, Cromwell retains his favored status with the king, and is sworn into the king's council after interpreting one of Henry's nightmares, about his deceased older brother, as a symbol that Henry should exert his power.

Cromwell continues to advise Anne, and works towards her ascension to queen in hopes that he will rise too. Just as the wedding appears imminent, Henry Percy, a former lover of Anne's, declares that he is her legal husband and still loves her. Though he knows what Percy is saying is true, Cromwell visits him on Anne's behalf and threatens him into silence, securing his position as a favourite in the Howard household.

King Henry takes Anne to France where, finally secure in her position, she and Henry marry in a private ceremony and consummate their relationship. She quickly becomes pregnant and Henry has her crowned queen in a ceremony which Cromwell organises with his usual perfection.

Historical background

Born to a working-class family of no position or name, Cromwell rose to become the right-hand man of Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, adviser to the King. He survived Wolsey's fall from grace to eventually take his place as the most powerful of Henry's ministers. In that role he observed turning points of English history, as Henry asserted his authority to declare his marriage annulled from Catherine of Aragon, married Anne Boleyn, broke from Rome, established the independence of the Church of England, and called for the dissolution of the monasteries.

The novel is a re-envisioning of historical and literary records; in Robert Bolt's play A Man for All Seasons Cromwell is portrayed as the calculating, unprincipled opposite of Thomas More's honour and rectitude. Mantel's novel offers an alternative to that portrayal, an intimate portrait of Cromwell as a tolerant, pragmatic, and talented man attempting to serve King, country, and family amid the political machinations of Henry's court and the religious upheavals of the Reformation, in contrast to More's viciously punitive adherence to the old Roman Catholic order that Henry is sweeping away.

Process

Mantel said she spent five years researching and writing the book, trying to match her fiction to the historical record.[6] To avoid contradicting history she created a card catalogue, organised alphabetically by character, with each card containing notes indicating where a particular historical figure was on relevant dates. "You really need to know, where is the Duke of Suffolk at the moment? You can't have him in London if he's supposed to be somewhere else," she explained.

In an interview with The Guardian, Mantel stated her aim to place the reader in "that time and that place, putting you into Henry's entourage. The essence of the thing is not to judge with hindsight, not to pass judgement from the lofty perch of the 21st century when we know what happened. It's to be there with them in that hunting party at Wolf Hall, moving forward with imperfect information and perhaps wrong expectations, but in any case moving forward into a future that is not pre-determined, but where chance and hazard will play a terrific role."[7]

Characters

Wolf Hall includes a large cast of fictionalised historical persons. In addition to those already mentioned, prominent characters include:

- Stephen Gardiner, Master Secretary to King Henry

- Princess Mary, the daughter and only surviving child of Henry and Catherine, later Queen Mary I of England.

- Mary Boleyn, sister of Anne

- Thomas Boleyn, father of Anne and Mary

- Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, Anne's uncle

- Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Jane Seymour, who later became the third of Henry's six wives

- Rafe Sadler, Thomas Cromwell's ward

Title

The title comes from the name of the Seymour family seat at Wolfhall or Wulfhall in Wiltshire; the title's allusion to the old Latin saying Homo homini lupus ("Man is wolf to man") serves as a constant reminder of the dangerously opportunistic nature of the world through which Cromwell navigates.[8]

Critical reaction

In The Guardian, Christopher Tayler wrote, "Wolf Hall succeeds on its own terms and then some, both as a non-frothy historical novel and as a display of Mantel's extraordinary talent. Lyrically yet cleanly and tightly written, solidly imagined yet filled with spooky resonances, and very funny at times, it's not like much else in contemporary British fiction. A sequel is apparently in the works, and it's not the least of Mantel's achievements that the reader finishes this 650-page book wanting more."[9]

Susan Bassnett, in Times Higher Education, wrote, "dreadfully badly written... Mantel just wrote and wrote and wrote. I have yet to meet anyone outside the Booker panel who managed to get to the end of this tedious tome. God forbid there might be a sequel, which I fear is on the horizon."[10]

In The Observer, Olivia Laing wrote, "Over two decades, she has gained a reputation as an elegant anatomiser of malevolence and cruelty. From the French Revolution of A Place of Greater Safety (1992) to the Middle England of Beyond Black (2005), hers are scrupulously moral – and scrupulously unmoralistic – books that refuse to shy away from the underside of life, finding even in disaster a kind of bleak and unconsoling humour. It is that supple movement between laughter and horror that makes this rich pageant of Tudor life her most humane and bewitching novel."[11]

Vanora Bennett in The Times wrote, "as soon as I opened the book I was gripped. I read it almost non-stop. When I did have to put it down, I was full of regret the story was over, a regret I still feel. This is a wonderful and intelligently imagined retelling of a familiar tale from an unfamiliar angle – one that makes the drama unfolding nearly five centuries ago look new again, and shocking again, too."[12]

A poll of literary experts by the Independent Bath Literature Festival voted Wolf Hall the greatest novel from 1995 to 2015.[13] It also ranked third in a BBC Culture poll of the best novels since 2000.[14] In 2019, The Guardian's list of the 100 best books of the 21st century ranked Wolf Hall first.[15]

Awards and nominations

- Winner – 2009 Booker Prize. James Naughtie, the chairman of the Booker prize judges, said the decision to give Wolf Hall the award was "based on the sheer bigness of the book. The boldness of its narrative, its scene setting...The extraordinary way that Hilary Mantel has created what one of the judges has said was a contemporary novel, a modern novel, which happens to be set in the 16th century".[16]

- Winner – 2009 National Book Critics Circle Award for fiction.

- Winner – 2010 Walter Scott Prize for historical fiction.[17]

- Winner – 2010 The Morning News Tournament of Books.[18]

- Winner – 2010 Audie Award for Literary Fiction for the audiobook narrated by Simon Slater[19]

- Winner – 2010 AudioFile magazine Earphone Award for the audiobook narrated by Simon Slater[20]

Adaptations

Stage

In January 2013, the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) announced it would stage adaptations by Mike Poulton of Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies in its Winter season.[21] The production transferred to London's Aldwych Theatre in May 2014, for a limited run until October.[22]

Producers Jeffrey Richards and Jerry Frankel brought the London productions of Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies, starring Ben Miles as Thomas Cromwell; Lydia Leonard as Anne Boleyn; Lucy Briers as Catherine of Aragon; and Nathaniel Parker as Henry VIII, to Broadway's Winter Garden Theatre[23] in March 2015 for a 15-week run. The double-bill has been re-titled Wolf Hall, Parts 1 and 2 for American audiences.[24] The play was nominated for eight Tony Awards, including Best Play.

Television

In 2012, the BBC announced it would adapt Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies for BBC Two, for broadcast in 2015.[25] On 8 March 2013, the BBC announced Mark Rylance had been cast as Thomas Cromwell.[26] The first episode was broadcast in the United States on PBS's Masterpiece Theatre, on 5 April 2015.[27] In June 2015, Amazon announced exclusive rights to stream Masterpiece programmes, including Wolf Hall, on its Amazon Prime Instant Video platform.[28]

See also

- Cultural depictions of Henry VIII of England

References

- "Wolf Hall wins the 2009 Man Booker Prize for Fiction : Man Booker Prize news". Themanbookerprize.com. 6 October 2009. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- "National Book Critics Circle: awards". Bookcritics.org. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- Skidelsky, William (13 May 2012). "The 10 best historical novels". The Observer. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- William Georgiades (4 May 2012). "Hilary Mantel's Heart of Stone". The Slate Book Review. Slate.com. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- Higgins, Charlotte (15 August 2012). "Hilary Mantel discusses Thomas Cromwell's past, presence and future". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- Alter, Alexandra (13 November 2009). "How to Write a Great Novel". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- Higgins, Charlotte (15 August 2012). "Hilary Mantel discusses Thomas Cromwell's past, presence and future". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- McAlpine, Fraser (4 April 2015). "10 Little-Known Facts About the Real Wolf Hall". Anglophenia. BBC America. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- Christopher Tayler (2 May 2009). "Henry's fighting dog". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- Bassnett, Susan (9 February 2012). "Pseuds' Corner: What Makes a Book 'Unpickupable?'". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 24 March 2012.

- Olivia Laing (26 April 2009). "Review: Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel". The Observer. London. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- Bennett, Vanora (25 April 2009). "Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel". The Times. London. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- Clark, Nick (22 February 2015). "Wolf Hall outstanding novel of our time, say Bath Festival judges". The Independent. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- Ciabattari, Jane (19 January 2015). "The 21st Century's 12 greatest novels". www.bbc.com. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- "The 100 best books of the 21st century". The Guardian. 21 September 2019. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- "Wolf Hall author takes home Booker prize". China.org.cn. 8 October 2009. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- Flood, Alison (1 April 2010). "Booker rivals clash again on Walter Scott prize shortlist". The Guardian. London.

- "April 5, 2010 Championship". The Morning News.

- "2010 Audie Awards® - APA". www.audiopub.org. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- "WOLF HALL by Hilary Mantel Read by Simon Slater | Audiobook Review". AudioFile Magazine. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- "David Tennant to play Richard II at the RSC". The Daily Telegraph. 23 January 2013. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- "Wolf Hall - Aldwych Theatre London - tickets, information, reviews". London Theatreland.

- "Wolf Hall Parts One & Two on Broadway". Wolf Hall Parts One & Two on Broadway.

- Hetrick, Adam & Shenton, Mark (10 September 2014). "Broadway Producers Eye Winter Garden with Brit Import of Wolf Hall Double-Bill". Playbill.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - "Wolf Hall adaptation planned for BBC Two". BBC News. 24 August 2012. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- "Mark Rylance set for Hilary Mantel TV drama". BBC News. 8 March 2013. Retrieved 14 October 2013.

- "Review: An arresting presence in 'Wolf Hall'". LA Times. 7 March 1965. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- Petski, Denise (30 June 2015). "Amazon Nabs Exclusive Licensing Rights To 'Wolf Hall', 'Grantchester' & More". Deadline. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

External links

- Hilary Mantel's Website

- Hilary Mantel's Facebook Fan Page

- Hilary Mantel on Wolf Hall, interview by Man Booker.

- Wolf Hall at complete review, an aggregation of reviews from papers and magazines.

- (Video) Hilary Mantel on Wolf Hall, The Guardian

- Rubin, Martin (10 October 2009). "A Man for All Tasks and Times". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 13 October 2009.