World's fair

A world's fair, also known as a universal exhibition or an expo, is a large international exhibition designed to showcase the achievements of nations.[1] These exhibitions vary in character and are held in different parts of the world at a specific site for a period of time, typically between three and six months.[1]

The term "world's fair" is commonly used in the United States,[2] while the French term, Exposition universelle ("universal exhibition"[3]) is used in most of Europe and Asia; other terms include World Expo or Specialised Expo, with the word expo used for various types of exhibitions since at least 1958.

Since the adoption of the 1928 Convention Relating to International Exhibitions, the Paris-based Bureau International des Expositions has served as an international sanctioning body for international exhibitions; four types of international exhibition are organised under its auspices: World Expos, Specialised Expos, Horticultural Expos (regulated by the International Association of Horticultural Producers) and the Milan Triennial.

Nur-Sultan, Kazakhstan, held the most recent Specialised Expo in 2017 while Dubai, United Arab Emirates hosted Expo 2020 (which was postponed to 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic).[4] Buenos Aires, Argentina, who had been selected to host the next Specialised Expo in 2023, announced its withdrawal with no reschedule date.[5][6]

History

In 1791 Prague organized the first World's Fair, Bohemia (modern-day Czech Republic).[7][8][9] The first industrial exhibition was on the occasion of the coronation of Leopold II as a king of Bohemia, which took place in Clementinum, and celebrated the considerable sophistication of manufacturing methods in the Czech lands during that time period.[10]

France had a tradition of national exhibitions, which culminated with the French Industrial Exposition of 1844 held in Paris. This fair was followed by other national exhibitions in Europe. In 1851, under the title "Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations", the World Expo was held in The Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, London, the United Kingdom. The Great Exhibition, as it is often called, was an idea of Prince Albert, Queen Victoria's husband, and is usually considered to be the first international exhibition of manufactured products. It influenced the development of several aspects of society, including art-and-design education, international trade and relations, and tourism.[11] This expo was the precedent for the many international exhibitions, later called World Expos, that have continued to be held to the present time.

The character of world fairs, or expositions, has evolved since the first one in 1851. Three eras can be distinguished: the era of industrialization, the era of cultural exchange, and the era of nation branding.[12]

Industrialization (1851–1938)

.jpg.webp)

The first era, the era of "industrialization", roughly covered the years from 1850 to 1938. In these years, world expositions were largely focused on trade and displayed technological advances and inventions. World expositions were platforms for state-of-the-art science and technology from around the world. The world expositions of 1851 London, 1853 New York, 1862 London, 1876 Philadelphia, Paris 1878, 1888 Barcelona, 1889 Paris, 1891 Prague, 1893 Chicago, 1897 Brussels, 1900 Paris, 1904 St. Louis, 1915 San Francisco, and 1933–34 Chicago were notable in this respect.[13] Inventions such as the telephone were first presented during this era. This era set the basic character of the world fair.[14]

Cultural exchange (1939–1987)

The 1939–40 New York World's Fair, and those that followed, took a different approach, one less focused on technology and aimed more at cultural themes and social progress. For instance, the theme of the 1939 fair was "Building the World of Tomorrow"; at the 1964–65 New York World's Fair, it was "Peace Through Understanding"; at the 1967 International and Universal Exposition in Montreal, it was "Man and His World". These fairs encouraged effective intercultural communication along with sharing of technological innovation.

The 1967 International and Universal Exposition in Montreal was promoted under the name Expo 67. Event organizers retired the term world's fair in favor of Expo (the Montreal Expos, a former Major League Baseball team, was named for the 1967 fair).[15]

Nation branding (1988–present)

From World Expo 88 in Brisbane onwards, countries started to use expositions as a platform to improve their national image through their pavilions. Finland, Japan, Canada, France, and Spain are cases in point. A major study by Tjaco Walvis called "Expo 2000 Hanover in Numbers" showed that improving national image was the main goal for 73% of the countries participating in Expo 2000. Pavilions became a kind of advertising campaign, and the Expo served as a vehicle for "nation branding". According to branding expert Wally Olins, Spain used Expo '92 and the 1992 Summer Olympics in Barcelona in the same year to underscore its new position as a modern and democratic country and to show itself as a prominent member of the European Union and the global community.

At Expo 2000 Hanover, countries created their own architectural pavilions, investing, on average, €12 million each.[16] Given these costs, governments are sometimes hesitant to participate, because the benefits may not justify the costs. However, while the effects are difficult to measure, an independent study for the Dutch pavilion at Expo 2000 estimated that the pavilion (which cost around €35 million) generated around €350 million of potential revenues for the Dutch economy. It also identified several key success factors for world-exposition pavilions in general.[17]

Types

At present there are two types of international exhibition: World Expos (formally known as International Registered Exhibitions) and Specialised Expos (formally known as International Recognised Exhibitions).[18] World Expos, previously known as universal expositions, are the biggest category events. At World Expos, participants generally build their own pavilions. They are therefore the most extravagant and most expensive expos. Their duration may be between six weeks and six months. Since 1995, the interval between two World Expos has been at least five years. World Expo 2015 was held in Milan, Italy, from 1 May to 31 October 2015.

Specialised Expos are smaller in scope and investments and generally shorter in duration; between three weeks and three months. Previously, these Expos were called Special Exhibitions or International Specialized Exhibitions but these terms are no longer used officially. Their total surface area must not exceed 25 ha (62 acres) and organizers must build pavilions for the participating states, free of rent, charges, taxes and expenses. The largest country pavilions may not exceed 1,000m2 (1⁄4 acre). Only one Specialised Expo can be held between two World Expos.[19]

An additional two types of international exhibition may be recognized by the BIE: horticultural exhibitions, which are joint BIE and AIPH-sanctioned 'garden' fairs in which participants present gardens and garden pavilions; and the semi-regular Milan Triennial (not always held every third year) art and design exhibition, held in Milan, Italy, with the BIE granting official international exhibition status to 14 editions of the Triennale between 1996 and 2016.[20]

World Expos

World Expos (formally known as International Registered Exhibitions) encompass universal themes that affect the full gamut of human experience, and international and corporate participants are required to adhere to the theme in their representations. Registered expositions are held every 5 years because they are more expensive as they require total design of pavilion buildings from the ground up. As a result, nations compete for the most outstanding or memorable structure—for example Japan, France, Morocco, and Spain at Expo '92. Sometimes prefabricated structures are used to minimize costs for developing countries, or for countries from a geographical block to share space (i.e. Plaza of the Americas at Seville '92).

In the 21st century the BIE has moved to sanction World Expos every five years; following the numerous expos of the 1980s and 1990s, some see this as a means to cut down potential expenditure by participating nations. The move was also seen by some as an attempt to avoid conflicting with the Summer Olympics. World Expos are restricted to every five years, with Specialized Expos in the in-between years.

Specialised Expos

Specialized Expos (formally known as International Recognized Exhibitions) are usually united by a precise theme—such as 'Future Energy' (Expo 2017 Astana), 'The Living Ocean and Coast' (Expo 2012 Yeosu), or 'Leisure in the Age of Technology' (Brisbane, Expo '88). Such themes are more specific than the wider scope of world expositions.

Specialized Expos are usually smaller in scale and cheaper to run for the host committee and participants because the architectural fees are lower and they only have to customize pavilion space provided free of charge from the Organiser, usually with the prefabricated structure already completed. Countries then have the option of 'adding' their own colours, design etc. to the outside of the prefabricated structure and filling in the inside with their own content.

List of expositions

List of official world expositions (Universal and International/Specialised) according to the Bureau International des Expositions.[21]

World Expos

| Dates[22] | Name of Exposition[22] | Country[22] | City[22] | Theme[22] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 04/1851 – 10/1851 | Great Exhibition | London | Industry of all Nations | |

| 05/1855 – 11/1855 | Exposition Universelle / Paris International | Paris | Agriculture, Industry and Art | |

| 05/1862 – 11/1862 | International Exhibition | London | Industry and Arts | |

| 04/1867 – 11/1867 | Exposition Universelle / Paris International | Paris | Agriculture, Industry and Arts | |

| 05/1873 – 10/1873 | Weltausstellung 1873 Wien / Austrian International Exposition | Vienna | Culture and Education | |

| 05/1876 – 11/1876 | Centennial Exposition | Philadelphia | Arts, Manufactures and Products of the Soil and Mine | |

| 05/1878 – 11/1878 | Exposition Universelle / Paris International Exposition | Paris | New Technologies | |

| 10/1880 – 04/1881 | Melbourne International Exhibition | Melbourne | Arts, Manufacturing, Agriculture and Industrial Products of all Nations | |

| 04/1888 – 12/1888 | Exposición Universal de Barcelona (1888) | Barcelona | Fine and Industrial Art | |

| 05/1889 – 10/1889 | Exposition Universelle / Paris International Exposition | Paris | French Revolution | |

| 05/1893 – 10/1893 | World's Columbian Exposition | Chicago | Discovery of America | |

| 05/1897 – 11/1897 | Brussels International Exposition | Brussels | Modern Life | |

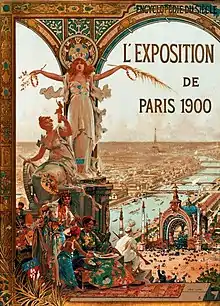

| 15/04/1900 - 12/11/1900 | Exposition Universelle | Paris | 19th century: an overview | |

| 04/1904 – 12/1904 | Louisiana Purchase Exposition | St. Louis | Louisiana Purchase | |

| 04/1905 – 11/1905 | Liège International (1905) | Liège | Commemoration of the 75th anniversary of independence | |

| 04/1906 – 11/1906 | Milan International | Milan | Transport | |

| 04/1910 – 11/1910 | Brussels International Exhibition | Brussels | Works of Art and Science, Agricultural and Industrial Products of All Nations | |

| 04/1913 – 11/1913 | Exposition universelle et international / Ghent International Exposition | Ghent | Peace, Industry and Art | |

| 02/1915 – 12/1915 | Panama–Pacific International Exposition | San Francisco | Inauguration of the Panama Canal | |

| 05/1929 – 01/1930 | Barcelona International Exposition | Barcelona | Arts, Industry and Sport | |

| 05/1933 – 10/1934 | Century of Progress | Chicago | The interdependence among industry and scientific research | |

| 04/1935 – 11/1935 | Brussels International Exposition | Brussels | Transports | |

| 05/1937 – 11/1937 | Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne / Paris International Exposition | Paris | Arts and Technology in modern life | |

| 02/1939 – 09/1940 | Golden Gate International Exposition | San Francisco | Pageant of the Pacific | |

| 04/1939 – 10/1940 | New York World's Fair | New York | Building The World of Tomorrow | |

| 12/1949 – 06/1950 | Exposition internationale du bicentenaire de Port-au-Prince | Port-au-Prince | The festival of Peace | |

| 07/1958 – 09/1958 | Brussels World's Fair | Brussels | A World View: A New Humanism | |

| 04/1962 – 10/1962 | Century 21 | Seattle | Man in the Space Age | |

| 04/1967 – 10/1967 | Expo 67 | Montreal | Man and His World | |

| 03/1970 – 09/1970 | Expo '70 | Osaka | Progress and Harmony for Mankind | |

| 04/1992 – 10/1992 | Expo '92 | Seville | The Era of Discovery | |

| 06/2000 – 10/2000 | Expo 2000 | Hanover | Man, Nature, Technology | |

| 03/2005 – 09/2005 | Expo 2005 | Aichi | Nature's Wisdom | |

| 05/2010 – 10/2010 | Expo 2010 | Shanghai | Better City, Better Life | |

| 05/2015 – 10/2015 | Expo 2015 | Milan | Feeding the planet, Energy for life | |

| 10/2021 – 04/2022 | Expo 2020 | Dubai | Connecting Minds, Creating the Future | |

| 04/2025 – 10/2025 | Expo 2025 | Osaka | Designing Future Society for Our Lives |

Specialised Expos

| Dates[23] | Name of Exposition[23] | Country | City[23] | Theme[23] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 05/1936 – 06/1936 | ILIS 1936 | Stockholm | Aviation | |

| 05/1938 – 05/1938 | Second International Aeronautic Exhibition | Helsinki | Aerospace | |

| 05/1939 – 09/1939 | Exposition internationale de l'eau (1939) | Liège | Art of Water | |

| 07/1947 – 08/1947 | International Exhibition on Urbanism and Housing | Paris | Urbanism and Housing | |

| 07/1949 – 08/1949 | Universal Sport Exhibition (1949) | Stockholm | Sport and physical culture | |

| 09/1949 – 10/1949 | The International Exhibition of Rural Habitat in Lyon | Lyon | Rural Habitat | |

| 04/1951 – 05/1951 | The International Textile Exhibition | Lille | Textile | |

| 07/1953 – 10/1953 | EA 53 | Rome | Agriculture | |

| 09/1953 – 10/1953 | Conquest of the Desert (exhibition) | Jerusalem | Conquest of the Desert | |

| 05/1954 – 10/1954 | The International Exhibition of Navigation (1954) | Naples | Navigation | |

| 05/1955 – 06/1955 | The International Expo of Sport (1955) | Turin | Sport | |

| 06/1955 – 08/1955 | Helsingborg exhibition 1955 | Helsingborg | Modern Man in the Environment | |

| 05/1956 – 06/1956 | Exhibition of citriculture | Beit Dagan | Citrus | |

| 07/1957 – 09/1957 | Interbau | West Berlin | Reconstruction of Hansa District | |

| 05/1961 – 10/1961 | Expo 61 | Turin | Celebration of centennial of Italian unity | |

| 06/1965 – 10/1965 | IVA 65 | Munich | Transport | |

| 04/1968 – 10/1968 | HemisFair '68 | San Antonio | Confluence of Civilizations in the Americas | |

| 08/1971 – 09/1971 | Expo 71 | Budapest | The Hunt through the World | |

| 05/1974 – 11/1974 | Expo '74 | Spokane | Celebrating Tomorrow's Fresh New Environment | |

| 07/1975 – 01/1976 | Expo '75 | Okinawa | The Sea We would like to See | |

| 06/1981 – 07/1981 | Expo 81 | Plovdiv | Hunting | |

| 05/1982 – 10/1982 | 1982 World's Fair | Knoxville | Energy Turns the World | |

| 05/1984 – 11/1984 | 1984 World's Fair | New Orleans | The World of Rivers– Fresh Water as a source of life | |

| 03/1985 – 09/1985 | Expo 85 (Tsukuba, Japan) | Tsukuba | Dwellings and Surroundings – Science and Technology for Man at Home | |

| 11/1985 – 11/1985 | Expo 85 (Plovdiv, Bulgaria) | Plovdiv | Inventions | |

| 05/1986 – 10/1986 | Expo 86 | Vancouver | Transportation and Communication: World in Motion – World in Touch | |

| 04/1988 – 10/1988 | Expo '88 | Brisbane | Leisure in the Age of Technology | |

| 06/1991 – 07/1991 | Expo 91 | Plovdiv | The activity of young people in the service of a World of Peace | |

| 05/1992 – 08/1992 | Expo Colombo '92 | Genoa | Christopher Columbus, The Ship and the Sea | |

| 08/1993 – 11/1993 | Expo '93 | Daejeon | The Challenge of a New Road of Development | |

| 05/1998 – 09/1998 | Expo '98 | Lisbon | The Oceans: A Heritage for the Future | |

| 06/2008 – 09/2008 | Expo 2008 | Zaragoza | Water and Sustainable development | |

| 05/2012 – 08/2012 | Expo 2012 | Yeosu | The Living Ocean and Coast | |

| 06/2017 – 09/2017 | Expo 2017 | Astana | Future Energy | |

| 01/2023 – 04/2023 | Expo 2023 | Buenos Aires | Creative industries in Digital Convergence |

Legacy

Most of the structures are temporary and are dismantled after the fair closes, except for landmark towers. By far the most famous of these is the Eiffel Tower, built for the Exposition Universelle (1889). Although it is now the most recognized symbol of its host city Paris, there were contemporary critics opposed to its construction, and demands for it to be dismantled after the fair's conclusion.[24]

Other structures that remain from these fairs:

- 1851 – London: The Crystal Palace, from the first World's Fair in London, designed so that it could be recycled to recoup losses, was such a success that it was moved and intended to be permanent, only to be destroyed by a fire in 1936.[25]

- 1876 – Philadelphia: The Centennial Exposition's main building, Memorial Hall, is still in Fairmount Park, Philadelphia, and serving as the new home for the Please Touch Museum. The space under the entrance to Memorial Hall houses a scale model of the entire Exposition.

- 1880 – Melbourne: The World Heritage-listed Royal Exhibition Building in Melbourne, constructed for the Melbourne International Exhibition.

- 1893 – Chicago: The Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago is housed in the former Palace of Fine Arts, one of the last remaining buildings of the World's Columbian Exposition. In conjunction with the fair, the Art Institute of Chicago building was built to house conferences, as the World's Congress Auxiliary Building. The intent or hope was to make all Columbian structures permanent, but most of the structures burned, possibly the result of arson during the Pullman Strike. The foundation of the world's first Ferris wheel, which operated at the Exposition, was unearthed on the Chicago Midway during a construction project by the University of Chicago, whose campus now surrounds the Midway. Relocated survivors include the Norway pavilion, a small house now at a museum in Wisconsin, and the Maine State Building, now at the Poland Springs Resort in Maine.

- 1894 – San Francisco: The Japanese Tea Garden in San Francisco's Golden Gate Park is the last major remnant of the California Midwinter International Exposition. Large ornamental wooden gates and a pagoda from the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition were brought in after the latter fair closed,[26] making the Tea Garden a rare if not unique instance of a survivor that incorporates architectural features from two completely separate fairs.

- 1897 – Nashville: A full-scale replica of the Parthenon was built for the Tennessee Centennial and International Exposition where it stands today in Nashville's Centennial Park. It features plaster reproductions of the Elgin Marbles and, in 1990, a re-creation of the original Athena Parthenos statue was installed inside just as it was in the original Parthenon in ancient Greece.

- 1900 – Paris: the Grand Palais and Petit Palais.

- 1904 – St. Louis: The St. Louis Art Museum in Forest Park, originally the Palace of the Fine Arts, and Brookings Hall at Washington University in St. Louis, are remnants of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (held a year late, as it was originally intended to be the centennial of the Louisiana Purchase. But organizers, and President Theodore Roosevelt, wanted the fair to be held during the Olympics which were moved from Chicago.), better known as the St. Louis World's Fair. The aviary in Forest Park gave root to the St. Louis Zoo.

_seen_from_the_southeast_with_the_Italian_Pavilion_in_the_foreground.jpg.webp) Brookings Hall at Washington University in St. Louis, the administration building of the 1904 World's Fair

Brookings Hall at Washington University in St. Louis, the administration building of the 1904 World's Fair - 1906 – Milan: The Civic Aquarium of Milan built for the Milan Exposition is still open after 100 years and was recently renovated. The International Commission on Occupational Health (ICOH) was settled in Milan during the fair and had its first congress in the Expo pavilions. In June 2006 the ICOH celebrated the first century of its life in Milan. An elevated railway with trains running at short intervals linked the fair to the city center. It was dismantled in the 1920s.

- 1909 – Seattle: The landscaping (by the Olmsted brothers) from the Alaska–Yukon–Pacific Exposition (AYPE) in Seattle still forms much of the University of Washington campus. The only major building left from the AYPE, Architecture Hall, is used by the university's architecture school.

- 1915 – San Francisco: The Palace of Fine Arts in San Francisco and its adjacent artificial lagoon are the only major remnants of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition still in their original locations on the former fairgrounds (now the city's Marina District neighborhood), but the building is almost entirely a reconstruction. The plaster-surfaced original, not intended to survive after the fair, was a crumbling ruin in 1964 when all but the steel framework was demolished so that it could be reproduced in concrete. The San Francisco Civic Auditorium, now the Bill Graham Civic Auditorium, is another major legacy of the fair but was built off-site in the city's Civic Center. The independent Panama-California Exposition in San Diego left a substantial legacy of permanent buildings and other structures which today define its site, San Diego's central Balboa Park, including the Prado walkway, the California Tower and Dome (now home to the Museum of Us), the 1,500-foot Cabrillo Bridge, the lily pond and botanical gardens, and the Spreckels Organ Pavilion.[27]

- 1929 – Seville & Barcelona: much survives from the two simultaneous fairs Spain hosted that year. The most famous are the remnants of the Ibero-American Exposition in Seville, in which the Spanish Pavilion's Plaza de España forms part of a large park and forecourt. Most of that fair's pavilions have survived and been adapted for other uses, with many of them becoming consulates-general for the countries that built them. The Barcelona International Exposition featured the famous German pavilion designed by Mies van der Rohe, which was demolished but later rebuilt on the original site.[28]

- 1936 – Johannesburg: The Empire Exhibition, South Africa was built close to the University of the Witwatersrand, and by the late 1970s the growth of the university was large enough to incorporate the permanent buildings from the exhibition. In 1985, the university purchased the South African Government Building; the two Heavy Machinery Halls, now called Empire Hall and the Dining Hall; the Hall of Transport; the Tower of Light; the Cape Dutch complex; and the Bien Donne Restaurant.

- 1939 – New York City: The New York City Building from the 1939's World Fair, was reused for the 1964 World's Fair and is now the Queens Museum. Parachute jump was a ride from the fair. It was moved to the Coney island boardwalk in Brooklyn.

- 1942 – Rome: A special case is the EUR quarter in Rome, built for a World's Fair planned for 1942 but cancelled because of World War II. Today it hosts governmental and private offices, and several museums.

- 1958 – Brussels: In Brussels, the Atomium still stands at the exposition site. It is a 165-billion-times-enlarged iron-crystal-shaped building. Until June 2012, the "American Theatre" on the Expo grounds was frequently used as a television studio by the VRT.

- 1962 – Seattle: The Space Needle theme building of the Century 21 Exposition commonly known as the Seattle World's Fair still stands as a Seattle icon and landmark. The Seattle Center Monorail, the other widely known futuristic feature of the fair, still operates daily. The US pavilion became the Pacific Science Center. The original exterior and roof of the Washington State Pavilion has been preserved as a landmark, and now is part of Climate Pledge Arena.

.jpg.webp)

- 1964 – New York City: many structures still stand

- The Unisphere, built for the second New York World's Fair, stands on its original site in Flushing Meadows, Queens

- The Singer Bowl stadium, since converted into Louis Armstrong Stadium, part of the Billie Jean King National Tennis Center, site of the US Open.

- New York Hall of Science, built for the fair, continues to operate as a science museum, similar to its original role

- The Port Authority Heliport and Exhibit is now the Terrace on the Park event and catering venue

- The New York State Pavilion is mostly derelict, but is still an icon, with its observation towers prominently featured in 1997's Men in Black. The Theaterama building is the only portion still maintained, and is used by the Queens Theater. There are plans to restore to the main Tent of Tomorrow building.

- The New York City Pavilion, a holdover form the 1939 fair, continues to serve as the home of the Queens Museum

- Other artifacts remain throughout the park, and many buildings were transported for use elsewhere and continue to function.

- 1967 – Montreal: Among the structures still standing from Expo 67 in Montreal are Moshe Safdie's Habitat 67, Buckminster Fuller's American pavilion the "Montreal Biosphere," the Jamaica Pavilion, the Tunisia Pavilion, and the French pavilion (now the Montreal Casino).

- 1968 – San Antonio: San Antonio kept the Tower of the Americas, the Institute of Texan Cultures and the Convention Center from HemisFair '68.

- 1970 – Osaka: The Tower of the Sun was left standing, but was neglected after the conclusion of the Expo '70. After restoration to the structure was completed, the museum inside the tower was re-opened on 18 March 2018.[29]

- 1974 – Spokane: Spokane still has its Riverfront Park that was created for Expo '74—the park remains a popular and iconic part of Spokane's downtown.

- 1982 – Knoxville: The Sunsphere from the Knoxville World's Fair remains as a feature of Knoxville's skyline.

- 1984 – New Orleans: The main pavilions of the 1984 New Orleans World's Fair became the Ernest N. Morial Convention Center, which is also known for its use as a shelter of last resort during Hurricane Katrina.

- 1986 – Vancouver: In Vancouver, many Expo 86 projects were designed as legacy projects. Of note are the Skytrain, Science World and Canada Place.

- 1988 – Brisbane: The Skyneedle, the symbol tower of Expo '88 in Brisbane, Queensland, Australia, still stands. Other survivors are the Nepalese Peace Pagoda of the Nepalese representation, now at the transformed World Expo '88 site South Bank Parklands, and the Japan Pond and Garden from the Japanese representation, now at the Brisbane Mount Cooth-tha Botanic Gardens. In 2018 the World Expo 88 Art Trail was re-birthed and dramatically expanded as part of the 30th Anniversary of World expo 88, now forming a Major tourist attraction in its own right.[30]

- 1992 – Seville: The pavilions of Expo '92 in Seville had been converted into a technological square and a theme park.

- 1998 – Lisbon: The main buildings of Expo '98 in Lisbon were completely integrated into the city itself and many of the art exhibition pieces still remain.

- 2005 – Nagoya: The home of Satsuki & Mei Kusakabe, built for the 2005 Expo in Aichi, remains operating at its original site in Morikoro Park and is a popular tourist attraction.

- 2010 – Shanghai: The China pavilion from Expo 2010 in Shanghai, the largest display in the history of the World Expo, is now the China Art Museum, the largest art museum in Asia.

- 2015 – Milan: The Italian Pavilion of Expo 2015 remains on the original site.

Some world's fair sites became (or reverted to) parks incorporating some of the expo elements, such as:

- Audubon Park, New Orleans: Site of New Orleans's World Cotton Centennial in 1884

- Jackson Park, Chicago and the Chicago Midway: Site of the 1893 Columbian Exposition

- Centennial Park, Nashville: Tennessee Centennial Expo in 1897

- Forest Park, Saint Louis: Home of the Saint Louis Louisiana Purchase Exposition of 1904

- San Diego: Panama-California Exposition (1915) & California Pacific International Exposition (1935)

- Seattle Center: Century 21 Exposition in 1962

- Flushing Meadows Park, Queens, New York City: Site of both the 1939 New York World's Fair and the 1964 New York World's Fair

- Montreal: Expo 67

- San Antonio: HemisFair '68

- Expo Commemoration Park, Osaka: Expo '70

- Riverfront Park, Spokane: Expo '74

- World's Fair Park, Knoxville: 1982 World's Fair

- Vancouver: Expo 86

- Brisbane: Expo '88: now represented with the South Bank Parklands[31]

- Seville: Expo '92

- Daejeon (Taejŏn): Expo '93

- Lisbon: Expo '98 was divided into several structures: Pavilhão Atlântico, Casino Lisboa, Oceanário and Pavilhão do Conhecimento.

- Shanghai Expo Park: Expo 2010

- Rho, Milan, Lombardy District: Expo 2015

Some pavilions have been transported overseas intact:

- The Argentine Pavilion from the 1889 Paris was relocated to Buenos Aires, Argentina until its demolition in 1932.

- The Chilean Pavilion from 1889 Paris is now in Santiago, Chile and following significant refurbishment in 1992 functions as the Museo Artequin[32]

- The Peruvian Pavilion from 1900 Paris is now in Lima, as home to the Military Academy of History.

- The Japanese Tower of the 1900 World's Fair in Paris was relocated to Laken (Brussels) on request of King Leopold II of Belgium.

- The Belgium Pavilion from the 1939 New York World's Fair was relocated to Virginia Union University in Richmond, Virginia.

- The USSR Pavilion from Expo 67 is now in Moscow.

- The Sanyo Pavilion from Expo '70 is the Asian Centre at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver.

- The Portugal Pavilion from Expo 2000 is now in Coimbra, Portugal.

- The United Arab Emirates Pavilion from Expo 2010 is now in Saadiyat Island in Abu Dhabi in UAE[33]

- The Bahrain Pavilion from Expo 2015 was relocated to Bahrain. The Azerbaijan Pavilion is in that country's capital Baku. The Chinese Pavilion was brought back to Qingdao and is on the site of the 2014 horticultural exhibition.

- The Save the Children Italy pavilion from Expo 2015 was dismantled and re-built as school for Syrian refugee children in Lebanon.[34][35]

The Brussels Expo '58 relocated many pavilions within Belgium: the pavilion of Jacques Chocolats moved to the town of Diest to house the new town swimming pool. Another pavilion was relocated to Willebroek and has been used as dance hall Carré[36] ever since. One smaller pavilion still stands on the boulevard towards the Atomium: the restaurant "Salon 58" in the pavilion of Comptoir Tuilier.

Many exhibitions and rides created by Walt Disney and his WED Enterprises company for the 1964 New York World's Fair (which was held over into 1965) were moved to Disneyland after the closing of the Fair. Many of the rides, including "It's a Small World", and "Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln", as well as the building that housed the Carousel of Progress are still in operation.

Disney had contributed so many exhibits to the New York fair in part because the corporation had originally envisioned a "permanent World's Fair" at the Flushing site. That concept instead came to fruition with the Disney Epcot theme park, an extension of the Walt Disney World Resort, near Orlando, Florida. Epcot has many characteristics of a typical universal exposition: national pavilions and exhibits concerning technology and/or the future, along with more typical amusement park rides. Meanwhile, several of the 1964 attractions that were relocated to Disneyland have been duplicated at the Walt Disney World Resort.

Occasionally other mementos of the fairs remain. In the New York City Subway system, signs directing people to Flushing Meadows, Queens remain from the 1964–65 event. In the Montreal subway at least one tile artwork of its theme, "Man and His World", remains. Also, a seemingly endless supply of souvenir items from fair visits can be found, and in the United States, at least, often turn up at garage or estate sales. Many fairs and expos produced postage stamps and commemorative coins.

The 1904 Olympic Games, officially the Games of the III Olympiad, were held in conjunction with the 1904 St. Louis fair, although no explicit coordination is evident. The Exposition Universelle (1900) Paris was also concomitant with the Olympic Games.

Current and upcoming expositions

2023 Buenos Aires

Expo 2023 was to be held at the Argentine capital and have a theme of "Science, Innovation, Art and Creativity for Human Development. Creative Industries in Digital Convergence".

Four countries had submitted bids to host Specialised Expo 2022/23:

Łódź

Łódź

The central Polish city of Łódź announced its candidacy to host EXPO 2022.[37] It was promoted in the Polish Pavilion at the EXPO 2015 in Milan. Consequently, the Polish government officially submitted Łódź's candidacy to the International Bureau of Expositions on 15 June 2016.[38] Minneapolis-Saint Paul made joint bids.

Minneapolis-Saint Paul made joint bids. Buenos Aires[39] (tentatively withdrawn)

Buenos Aires[39] (tentatively withdrawn) Los Angeles[40] (cancelled)

Los Angeles[40] (cancelled) Rio de Janeiro (cancelled)

Rio de Janeiro (cancelled)

At the end of the project examination phase, BIE Member States voted for Buenos Aires as the host city of Expo 2022/23 via a secret ballot at the BIE General Assembly, held in November 2017.[41]

However, Buenos Aires announced its withdrawal with no reschedule date.[5][6]

2025 Osaka

Expo 2025 will be held at the Japanese city of Osaka and will have a theme of "Designing Future Society for Our Lives!”.

Four countries had submitted bids to host World Expo 2025:

Osaka made its official bid for the Expo on 24 April 2017[42] with the theme "Designing Future Society for Our Lives".[43]

The Azerbaijani capital entered its candidacy before the deadline[44] under the theme "Human Capital".

The French capital was the first to declare its candidacy,[45] under the theme "Sharing our Knowledge, Caring for our Planet".[46] The candidacy was withdrawn in January 2018 because of budget constraints.[47]

The Russian city entered its candidacy on 22 May 2017[45] under the theme "Changing world: inclusive innovation is for our children and future generations".

At the end of the project examination phase, BIE Member States voted for Osaka as the host city of Expo 2025 via a secret ballot at the BIE General Assembly, held in November 2018.

2030

Potential host countries may apply to host Expo 2030 between 6 and 9 years before its proposed opening date.[48] Once one country has submitted an application, alternative countries have 6 months to submit theirs.[48]

At the 167th BIE general assembly both South Korea and Russia indicated their intention to bid for this expo.[49]

Non-BIE efforts

The only Expo to be held without BIE approval was the 1964–1965 New York World's Fair;[50] the sanctioning organization at Paris denied it "official" status because its president, Robert Moses, would not comply with the BIE rule limiting the duration of universal expositions to six months. The Fair proceeded without BIE approval, and turned to tourism and trade organizations to host national pavilions in lieu of official government sponsorship. Many countries participated in that fair, including several newly independent African and Asian states.[51] The two World's Fairs in New York (1939–40 and 1964–65) and the Century of Progress in Chicago (1934-1935) are the only two-year world expositions that have been held.

Frederick Pittera, a producer of international exhibitions and author of the history of world's fairs in the Encyclopædia Britannica and Compton Encyclopedia, was commissioned by Mayor Robert F. Wagner Jr. of New York City in 1959 to prepare the first feasibility studies for the 1964 New York World's Fair. Pittera was joined in his study by Austrian architect Victor Gruen (Inventor of the 'Shopping Mall'). The Eisenhower Commission ultimately awarded the world's fair bid to New York City against several major U.S. cities.[52]

Because the U.S. government withdrew its membership in the Bureau International des Expositions from 2002 to 2017,[53] Worlds Fair Nano is the first private effort in history to host a six-month World's Fair.[54] Worlds Fair Nano is organizing a series of mini-World's Fairs around the country called World's Fair Nano in cities like San Francisco[55] and New York City[56] in order to build excitement for the six month World's Fair, which Worlds Fair Nano hopes to organize within the decade.

The Philippines International Fair of 1953 is another non-BIE exposition. It featured participation from 12 nations (11 foreign plus the host Philippines). It was the first world exposition after World War 2 and the first ever in Asia.[57][58]

The Los Angeles World's Fair is another non-BIE effort.[59]

International Horticultural Exhibition

The BIE, since 1959[60] grants recognition to the International Horticultural Exhibitions (Category A1) approved by the International Association of Horticultural Producers (AIPH) subject to it meeting certain criteria including being approved by the BIE general assembly.[61]

International Horticultural Exhibitions (upcoming in italics):

1960 Rotterdam (Netherlands)

1960 Rotterdam (Netherlands) 1963 Hamburg (Germany)

1963 Hamburg (Germany) 1964 Vienna (Austria)

1964 Vienna (Austria) 1969 Paris (France)

1969 Paris (France) 1972 Amsterdam (Netherlands)

1972 Amsterdam (Netherlands) 1973 Hamburg (Germany)

1973 Hamburg (Germany) 1974 Vienna (Austria)

1974 Vienna (Austria).svg.png.webp) 1980 Montreal (Canada)

1980 Montreal (Canada) 1982 Amsterdam (Netherlands)

1982 Amsterdam (Netherlands) 1983 Munich (Germany)

1983 Munich (Germany) 1984 International Garden Festival Liverpool (United Kingdom)

1984 International Garden Festival Liverpool (United Kingdom) 1990 Osaka (Japan)

1990 Osaka (Japan) 1992 Zoetermeer (Netherlands)

1992 Zoetermeer (Netherlands) 1993 Stuttgart (Germany)

1993 Stuttgart (Germany) 1999 Kunming (China)

1999 Kunming (China) 2002 Floriade in Haarlemmermeer (Netherlands)

2002 Floriade in Haarlemmermeer (Netherlands) 2003 Rostock (Germany)

2003 Rostock (Germany) 2006–7 Chiang Mai (Thailand)[62]

2006–7 Chiang Mai (Thailand)[62] 2012 Floriade in Venlo (Netherlands)

2012 Floriade in Venlo (Netherlands) 2016 Antalya (Turkey)

2016 Antalya (Turkey) 2019 Beijing (China)

2019 Beijing (China) 2023 World Horticultural Exposition (Doha, Qatar)[63]

2023 World Horticultural Exposition (Doha, Qatar)[63] 2022 Almere (Netherlands)[64]

2022 Almere (Netherlands)[64] 2024 Łódź (Poland)

2024 Łódź (Poland)

See also

- Agricultural show

- State fair

References

- "world's fair | History, Instances, & Facts | Britannica". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- Britannica. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- "exposition". Cambridge French-English Dictionary.

- The Expo was postponed from 2020 to 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic

- "La Argentina se bajó de la organización y no será sede de la Expo Mundial 2023, un megaevento de impacto global – LA NACION". La Nación (in Spanish).

- "Argentina renunció a ser sede de la Expo Mundial 2023 – Diario El Sol. Mendoza, Argentina" (in Spanish).

- Kárníková, Ludmila (1965). Vývoj obyvatelstva v českých zemích 1754-1914 (1 ed.). Praha: Nakladatelství Československé akademie věd. pp. 401, [2] s. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- Klíma, Arnošt (1 February 1974). "The Role of Rural Domestic Industry in Bohemia in the Eighteenth Century". The Economic History Review. 27 (1): 48–56. doi:10.2307/2594203. JSTOR 2594203. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- Rudolph, Richard F. (1975). "The Pattern of Austrian Industrial Growth from the Eighteenth to the Early Twentieth Century". Austrian History Yearbook. Cambridge University Press. 11: 3–25. doi:10.1017/S0067237800015216. S2CID 145393467. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- "The era of enlightenment". Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- John R. Davies in Findling and Pelle (2008), "Encyclopedia of World's Fairs and Expositions", pp. 13–14

- Walvis, Tjaco, ed. (April 2004). "Three eras of World Expositions: 1851–present". Cosmopolite: Stardust World Expo & National Branding Newsletter. Amsterdam: Stardust New Ventures (5): 1.

- "world's fair | History, Instances, & Facts". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Abbattista, Guido; Iannuzzi, Giulia (2016). "World Expositions as Time Machines: Two Views of the Visual Construction of Time between Anthropology and Futurama". World History Connected. 13 (3).

- Ted Dykstra (Director) (2004). Expo'67: Back to the future (DVD). Canada: CBC Home Video.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 August 2012. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Tjaco Walvis (2003), "Building Brand Locations", Corporate Reputation Review, Vol.5, No.4, pp. 358–366

- "The Expos". Archived from the original on 11 March 2018. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- Based on: BIE Convention

- "Triennal di Milano." Bureau International des Expositions (BIE-Paris.org). Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- "Official Site of he Bureau International des Expositions". Bie-paris.org. 27 June 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- "All-world-expos". Retrieved 14 July 2006.

- "All-specialised-expos". Retrieved 14 July 2006.

- "The Controversy about the Eiffel Tower". Paris Eiffel Tower News. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- "Crystal Palace: Joseph Paxton – Transported by moving company". Retrieved 19 June 2014.

- PPIE Found Remnants: Architecture: Japanese Gates and Pagoda. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- "Balboa Park History". Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- Expo, International Expositions 1851–2010, Anna Jackson, 2008

- "Tower of the Sun – Suita-shi, Japan – Atlas Obscura". Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- "World Expo '88 Public Art Trail – 30th Anniversary." Brisbane City Council (Brisbane.qld.gov.au). Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- "Home – South Bank – Visitor Info – What's On – Shopping – Dining – Attractions and more". Visit South Bank. 4 June 2009. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- "Artequin". Artequin.cl. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- "The UAE in World Expos | World Expos | Expo 2020, Dubai, UAE". Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- "Jarahieh School for Syrian refugee children in Lebanon". Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- "La nuova vita del villaggio Expo: una scuola in Libano". 29 December 2016. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- "Home – Carré". Carre.be. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- "EXPO for Łódź. 60,000 visitors every day". Gazeta Wyborcza (in Polish). Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- "Official Site of the Bureau International des Expositions". Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- "Specialised Expo 2022/23". BIE Paris. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- "Los Angeles World's Fair".

- "Election". BIE Paris. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- "Osaka launches formal bid to host 2025 World Expo". mainichi.jp/english/. Archived from the original on 28 April 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- "Japan submits bid for World Expo 2025". bie-paris.org. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- "Baku bids for World Expo 2025". azernews.az. 23 May 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- "World Expo 2025". bie-paris.org. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- "Application idea". expofrance2025.com. Archived from the original on 12 August 2017. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- "France drops bid to host 2025 World Expo". Reuters. 21 January 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- "World Expo 2030". Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- "Republic of Korea organises 7th conference on Busan Expo project". Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- Harrison Jacobs (22 April 2014). "15 Gorgeous Retro-Future Photos From The 1964 World's Fair". Business Insider. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- Findling and Pelle, Encyclopedia of World's Fairs and Expositions, 9780786434169 p330

- "Building the Fair – Five Men". nywf64.com. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- "The United States becomes the 170th Member State of the BIE". 26 May 2017.

- "Bringing the World's Fair Back to the U.S." Bloomberg L.P. 17 December 2015. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- Stone, Zara. "Inside San Francisco's 21st Century World's Fair". Forbes. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- "Virtual reality features heavily at upcoming Worlds Fair Nano in Brooklyn". Full Dive Gamer. 27 August 2017. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- "Remembering the Forgotten 1953 Manila World's Fair".

- "Philippines International fair 1953" – via YouTube.

- "Los Angeles Wants a Transit-Themed World's Fair, and It Might Actually Be a Great Idea". Bloomberg L.P. 17 April 2015. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- "Horticultural Expos". Retrieved 26 May 2017.,

- "International Horticultural Exhibition". Bie-paris.org. 18 April 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- "Exhibitions, actual programme". AIPH. 11 January 2011. Archived from the original on 15 July 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- "Expo 2023 Doha Qatar – Change of dates – Bureau International des Expositions (BIE)". bie-paris.org. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- "Floriade Amsterdam Almere 2022 (A1) – International Association of Horticultural Producers". aiph.org. Archived from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

Further reading

- Geppert, Alexander C. T. (2010). Fleeting Cities. Imperial Expositions in Fin-de-Siècle Europe. Basingstoke/New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Geppert, Alexander C.T., World's Fairs, EGO – European History Online, Mainz: Institute of European History, 2018, retrieved: 8 March 2021 (pdf).

- Findling, John E.; Pelle, Kimberly D., eds. (2008). Encyclopedia of World's Fairs and Expositions. Jefferson, NC and London: McFarland.

- López César, Isaac; Estévez‐Cimadevila, Javier (2018). "World Expos. Five structural approaches". Estoa. 7 (13): 7–22. doi:10.18537/est.v007.n013.a1.

External links

- Bureau International des Expositions Official website

- Expo Bids: The World's Fair Bid Tracker Archived 4 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine Information about bids for future world's fairs

- Expo FAQs General World's Fair questions answered at Celebrate 88

- Exposition Medals Award medals of American World's Fairs and Expos

- "Exposition Posters". Paintings and Drawings. Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 27 October 2007. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- "A Treasury of World's Fair Art and Architecture: A Digital Archive, 1851–1986". Essays, images, virtual exhibits, postcards and ephemera from the World's Fair Ephemeral and Graphic Materials collection. University of Maryland Libraries, Digital Collections. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - Weltaustellung.net Photographs from thirteen fairs, includes stereograms

- World Expos. A history of structures. Preview of sample pages of book by Isaac López Cesar about the structures of the buildings built for World Expos. Supported by the BIE.

- World's Fairs and the Landscapes of the Modern Metropolis Posters, photographs, pamphlets, commemorative books, maps, government reports, and ephemera from the collection of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University

- "World's Fairs. Structure laboratory: the contribution of the buildings built for the World's Fairs to the history of architecture structural typologies". PhD thesis by Isaac López César.