Books of Kings

The Book of Kings (Hebrew: סֵפֶר מְלָכִים, Sēfer Məlāḵīm) is a book in the Hebrew Bible, found as two books (1–2 Kings) in the Christian Old Testament. It concludes the Deuteronomistic history, a history of Israel also including the books of Joshua, Judges and Samuel.

| |||||

| Tanakh (Judaism) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Old Testament (Christianity) | |||||

|

|

|||||

| Bible portal | |||||

Biblical commentators believe the Books of Kings were written to provide a theological explanation for the destruction of the Kingdom of Judah by Babylon in c. 586 BCE and to provide a foundation for a return from Babylonian exile.[1] The two books of Kings present a history of ancient Israel and Judah, from the death of King David to the release of Jehoiachin from imprisonment in Babylon—a period of some 400 years (c. 960 – c. 560 BCE).[1] Scholars tend to treat the books as consisting of a first edition from the late 7th century BCE and of a second and final edition from the mid-6th century BCE.[2][3]

Contents

The Jerusalem Bible divides the two Books of Kings into eight sections:

- 1 Kings 1:1–2:46. The Davidic Succession

- 1 Kings 3:1–11:43. Solomon in all his glory

- 1 Kings 12:1–13:34. The political and religious schism

- 1 Kings 14:1–16:34. The two kingdoms until Elijah

- 1 Kings 17:1 – 2 Kings 1:18. The Elijah cycle

- 2 Kings 2:1–13:25. The Elisha cycle

- 2 Kings 14:1–17:41. The two kingdoms to the fall of Samaria

- 2 Kings 18:1–25:30. The last years of the kingdom of Judah

1 Kings

David is by now old, and so his attendants look for a virgin to look after him. They find Abishag, who looks after him but they do not have sexual relations. Adonijah, David's fourth son, born after Absalom, decides to claim the throne, so, having received the loyalty of Joab, David's general, and Abiathar the priest, he begins a coronation procession. He begins the festivities by offering sacrifices at En Rogel in the presence of his brothers and the royal officials, but does not invite Nathan the prophet; Benanaiah, captain of the kings bodyguard (or indeed the bodyguard itself); or even his own brother Solomon.

Nathan comes to Bathsheba, Solomon's mother, and informs her what is going on. She goes to David and reminds him that he said Solomon would be his successor. As she is speaking to him and explaining her fears that she and Solomon will be treated as criminals after his death, Nathan enters and explains the full situation to David. David reaffirms his promise that Solomon will be king after him and arranges for him to be anointed at the Gihon Spring. The anointing is performed by Zadok the priest. The trumpets are sounded and the population of Jerusalem proclaims him king. This is heard by Adonijah and his fellow feasters, but they do not know what is happening until Abiathar's son Jonathan arrives and informs them. It turns out that by this point Solomon has been seated on the throne and David has been informed, thus completing the ceremony. Adonijah claims sanctuary, but Solomon decides to spare him unless he does something evil.

David advises his son on how to be a good king and to punish David's enemies, and then dies. Adonijah comes to Bathsheba and asks to marry Abishag. Solomon suspects this request is to strengthen Adonijah's claim to the throne and has Benaiah put him to death. He then takes away Abiathar's priesthood as punishment for supporting Adonijah, thus fulfilling the prophecy made to Eli at the start of 1 Samuel. Joab hears what is going on and himself claims sanctuary, but when he refuses to come out of the tabernacle, Solomon instructs Benaiah to kill him there. He then replaces Joab with Benaiah and Abiathar with Zadok. Solomon then instructs Shimei, the Benjaminite who cursed David as he was fleeing from Absalom and whom David has instructed Solomon to punish, to move to Jerusalem and not to leave. One day, two of Shimei's slaves run away to Gath and Shimei pursues them. When he returns to Jerusalem, Solomon has him put to death for leaving Jerusalem and for earlier cursing David. Solomon is finally established as king.

Solomon makes an alliance with Egypt and marries Pharaoh's daughter. After this, he continues the ancient practice of travelling between the high places and offering sacrifices. When he is at Gibeon, God speaks to him in a dream and offers him anything he asks for. Solomon, being young, asks for the wisdom to lead his people well. God is pleased he asks for this and grants him not only this, but also wealth, honour and, if Solomon keeps his commandments as well as David did, long life. Solomon returns to Jerusalem and holds a feast in front of the Ark of the Covenant.

Solomon's newfound wisdom soon gets put to the test when two prostitutes come to Solomon with an issue. During the night, it seems, one of them had rolled over in their shared bed onto her son, killing him, resulting in a situation where the son of one of them is alive and the other is dead, but they cannot agree which is which. Solomon calls for a sword and threatens to cut the living child in two and give a half to each woman. While the mother of the dead child is happy to let the child die, saying that if she can't have him the other one can't either, the mother of the living child pleads that he be given to the other woman as long as he isn't killed. Solomon now knows who the child's true mother is and gives him to her alive. This judgment amazes the Israelites, and Solomon gains a reputation for his wisdom. Solomon uses his wisdom to appoint a cabinet and reorganise the governance of Israel at a local level. In accordance with God's promises to both David and Solomon, the nation of Israel prospers and Solomon's provisions increase. Equally, Solomon's wisdom continues to increase in all areas.

Hiram I, king of Tyre sends an embassy to Jerusalem, hoping to continue the good relationship he had with David. Solomon writes back stating his intention to fulfil David's vow of building a temple. Hiram agrees to supply him with wood in exchange for provisions for his palace, and the two sign a treaty. Solomon and Hiram put together groups of men to transport the logs and cut stone. By this point it has been 480 years since the Exodus, and Solomon begins to build the Temple. It takes him seven years. He also builds himself a palace, which takes him thirteen years. Once the Temple building is finished, Solomon hires a Tyrian half-Naphtalite named Huram to create the furnishings of the Temple.

Once everything is finished, Solomon has the things which David prepared for the Temple brought in. He then organises a ceremony during which the priests carry the Ark of the Covenant, containing the Tablets of the Law, into the Temple. A cloud fills the Temple, preventing the priests from continuing the ceremony. Solomon explains that this is the presence of God, and takes the opportunity to make a dedication speech, in which he expresses thanksgiving that he could build the Temple, and sees it as the fulfilment of God's promise to Moses. He then begins to pray, emphasising his humility in building the Temple and asking God to act as he has promised to in relation to various functions of the Temple. He then makes another speech, largely re-iterating the points he made in the first speech. The dedication is completed with sacrifices, a celebration is held for fourteen days, and everyone returns home. God speaks to Solomon and accepts his prayer, re-affirming his vow to David that his House will be kings forever unless they begin worshipping idols.

Solomon gives twenty towns in Galilee to Hiram as thanks for his help, but they are virtually worthless. He begins building and improvement works in various cities in addition to his major projects in Jerusalem and puts the remaining Canaanites into slavery. He also fulfils his religious duties and builds a navy.

The Queen of Sheba hears of Solomon's wisdom and travels to Jerusalem to meet him with her large and gold-laden caravan. Solomon satisfies her with his wisdom and wealth, and she praises him, saying she did not fully believe the stories about Solomon until she came to see him. The Queen gives Solomon 120 talents and a large amount of spices and precious stones. To compete with this, Hiram sends a large amount of valuable wood and precious stones. Solomon also gives the Queen gifts and she returns to her country. Solomon by now has 666 talents of gold, and decides to make shields and cups out of gold. He also maintains trading relations with Hiram, from whose country he receives many exotic goods. Overall, Israel becomes a net exporter of golden goods.

Solomon amasses 700 wives and 300 concubines, many from foreign countries, including from countries God told the Israelites not to intermarry with. Solomon begins to adopt elements from their religions, including worship of the goddess Astarte and the evil Ammonite god Moloch, thus breaking the commandment 'Thou shalt have no other gods before me'. He builds shrines in Jerusalem to Moloch and Chemosh, an evil Moabite god. God informs Solomon that because he has broken this commandment, the entire kingdom except one tribe will be taken away from his son.

At the same time, Solomon begins to amass enemies. When Joab committed genocide against the Edomites, a young prince named Hadad managed to escape Egypt, where he became a favourite at Pharaoh's court, with Pharaoh giving him his own sister-in-law's hand in marriage and incorporating him into palace life. When Hadad hears Joab and David are dead, he returns to Edom. Another enemy is Rezon the Syrian, a survivor of the defeat of the Zobahite army during David's reign, who allies himself with Hadad and causes havoc for Israel from his base in Damascus.

Before Solomon can deal with these enemies, he must quash a revolt at home. He appoints one of his officers, Jeroboam, to supervise the building of the palace terraces and reconstruction of the city walls. When this turns out well, he puts him in charge of the workforce of the Tribe of Joseph. One day, Jeroboam meets the prophet Ahijah the Shilonite, who is wearing a new cloak, on the road out of Jerusalem. Ahijah tears his cloak into twelve parts and gives ten of them to Jeroboam, saying that Jeroboam will rule over ten tribes of Israel upon Solomon's death as punishment for Solomon's idol worship. In addition to this, God makes the same promise to Jeroboam as he did to David. Solomon tries to kill Jeroboam, but he flees to Egypt. Solomon dies after having reigned for forty years and is succeeded by his son Rehoboam.

Rehoboam travels to Shechem to be proclaimed king. Upon hearing this, Jeroboam returns from Egypt and asks for the people to be treated better than under Solomon. Three days later, having ignored his older advisors' advice to agree and instead listened to his friends, he instead says that he will treat them much worse than Solomon. This greatly displeases the Israelites, who begin to question why they are united under a single king who clearly doesn't care about them at all. When he sends a new minister of forced labour named Adoniram, they stone him to death. Rehoboam returns to safety in Jerusalem. The Israelites proclaim Jeroboam king. Judah remains loyal to Rehoboam, and he also controls Benjamin. From these two tribes, Rehoboam amasses an army to attack the north, but the prophet Shemaiah prevents the war.

Back in Shechem, Jeroboam becomes worried about the possible return of his tribes to loyalty to the House of David, and decides the best way to prevent this is to stop them worshipping the God of Israel, since he considers the point at which they are most likely to defect to be when they travel to Jerusalem to offer sacrifices. To this end, he sets up golden calves at altars at Bethel and Dan and appoints his own priests and festivals, thus creating a specific Israelite religion. One day, a prophet comes by and announces that some day a Davidic king named Josiah will be born and violently abolish Jeroboam's religion. Seeking to seize him, Jeroboam stretches out his hand, but it becomes withered and, as a sign, the altar splits open and its ashes pour out. After the prophet heals Jeroboam's hand, the king invites him to a meal, but the prophet says that God told him not to eat there. On his way home, another prophet invites him in for dinner by lying about a prophecy. As punishment, God has the initial prophet killed by a lion. The prophet who invited him in buries him in his own tomb, and tells his sons to bury him in the same tomb and prophecies that the prophecy made to Jeroboam will come true. Despite all this, Jeroboam does not change his ways.

The kings who follow Rehoboam in Jerusalem continue the royal line of David, i.e., they inherit Yahweh's promise to David.

In the north, dynasties follow each other in rapid succession, and the kings are uniformly bad, i.e., they fail to follow Yahweh alone.

2 Kings

At length God brings the Assyrians to destroy the northern kingdom, leaving Judah as the sole custodian of the promise.

Hezekiah, the 13th king of Judah, does "what [is] right in the Lord's sight just as his ancestor David had done".[4] He institutes a far-reaching religious reform: centralising sacrifice at the temple in Jerusalem, and destroying the images of other gods. Yahweh saves Jerusalem and the kingdom from an invasion by Assyria. But Manasseh, the next king of Judah, reverses the reforms, and God announces that he will destroy Jerusalem because of this apostasy by the king. Manasseh's righteous grandson Josiah reinstitutes the reforms of Hezekiah, but it is too late: God, speaking through the prophetess Huldah, affirms that Jerusalem shall be destroyed after the death of Josiah.

In the final chapters, God brings the Neo-Babylonian Empire of King Nebuchadnezzar against Jerusalem. Yahweh withholds aid from his people; Jerusalem is razed and the Temple destroyed; and the priests, prophets and royal court are led into captivity. The final verses record how Jehoiachin, the last king, is set free and given honour by the king of Babylon.[5]

Composition

Textual history

In the Hebrew Bible (the Bible used by Jews), First and Second Kings are a single book, as are the First and Second Books of Samuel. When this was translated into Greek in the last few centuries BCE, Samuel was joined with Kings in a four-part work called the Book of Kingdoms. Orthodox Christians continue to use the Greek translation (the Septuagint), but when a Latin translation (called the Vulgate) was made for the Western church, Kingdoms was first retitled the Book of Kings, parts One to Four, and eventually both Samuel and Kings were separated into two books each.[6]

Thus, the books now commonly known as 1 Samuel and 2 Samuel are known in the Vulgate as 1 Kings and 2 Kings (in imitation of the Septuagint). What are now commonly known as 1 Kings and 2 Kings would be 3 Kings and 4 Kings in old Bibles before the year 1516, such as in the Vulgate and the Septuagint.[7] The division known today, used by Protestant Bibles and adopted by Catholics, came into use in 1517. Some Bibles—for example, the Douay Rheims Bible—still preserve the old denomination.[8]

Deuteronomistic history

According to Jewish tradition the author of Kings was Jeremiah, who would have been alive during the fall of Jerusalem in 586 BCE.[9] The most common view today accepts Martin Noth's thesis that Kings concludes a unified series of books which reflect the language and theology of the Book of Deuteronomy, and which biblical scholars therefore call the Deuteronomistic history.[10] Noth argued that the History was the work of a single individual living in the 6th century BCE, but scholars today tend to treat it as made up of at least two layers,[11] a first edition from the time of Josiah (late 7th century BCE), promoting Josiah's religious reforms and the need for repentance, and (2) a second and final edition from the mid-6th century BCE.[2][3] Further levels of editing have also been proposed, including: a late 8th century BCE edition pointing to Hezekiah of Judah as the model for kingship; an earlier 8th-century BCE version with a similar message but identifying Jehu of Israel as the ideal king; and an even earlier version promoting the House of David as the key to national well-being.[12]

Sources

The editors/authors of the Deuteronomistic history cite a number of sources, including (for example) a "Book of the Acts of Solomon" and, frequently, the "Annals of the Kings of Judah" and a separate book, "Chronicles of the Kings of Israel". The "Deuteronomic" perspective (that of the book of Deuteronomy) is particularly evident in prayers and speeches spoken by key figures at major transition points: Solomon's speech at the dedication of the Temple is a key example.[2] The sources have been heavily edited to meet the Deuteronomistic agenda,[13] but in the broadest sense they appear to have been:

- For the rest of Solomon's reign the text names its source as "the book of the acts of Solomon", but other sources were employed, and much was added by the redactor.

- Israel and Judah: The two "chronicles" of Israel and Judah provided the chronological framework, but few details apart from the succession of monarchs and the account of how the Temple of Solomon was progressively stripped as true religion declined. A third source, or set of sources, were cycles of stories about various prophets (Elijah and Elisha, Isaiah, Ahijah and Micaiah), plus a few smaller miscellaneous traditions. The conclusion of the book (2 Kings 25:18–21, 27–30) was probably based on personal knowledge.

- A few sections were editorial additions not based on sources. These include various predictions of the downfall of the northern kingdom, the equivalent prediction of the downfall of Judah following the reign of Manasseh, the extension of Josiah's reforms in accordance with the laws of Deuteronomy, and the revision of the narrative from Jeremiah concerning Judah's last days.[14]

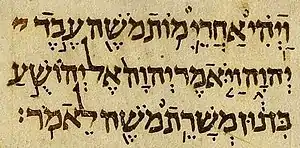

Manuscript sources

Three of the Dead Sea Scrolls feature parts of Kings: 5QKgs, found in Qumran Cave 5, contains parts of 1 Kings 1; 6QpapKgs, found in Qumran Cave 6, contains 94 fragments from all over the two books; and 4QKgs, found in Qumran Cave 4, contains parts of 1 Kings 7–8.[15][16][17] The earliest complete surviving copy of the book(s) of Kings is in the Aleppo Codex (10th century CE).[18]

Themes and genre

Kings is "history-like" rather than history in the modern sense, mixing legends, folktales, miracle stories and "fictional constructions" in with the annals, and its primary explanation for all that happens is God's offended sense of what is right; it is therefore more fruitful to read it as theological literature in the form of history.[19] The theological bias is seen in the way it judges each king of Israel on the basis of whether he recognises the authority of the Temple in Jerusalem (none do, and therefore all are "evil"), and each king of Judah on the basis of whether he destroys the "high places" (rivals to the Temple in Jerusalem); it gives only passing mention to important and successful kings like Omri and Jeroboam II and totally ignores one of the most significant events in ancient Israel's history, the battle of Qarqar.[20]

The major themes of Kings are God's promise, the recurrent apostasy of the kings, and the judgement this brings on Israel:[21]

- Promise: In return for Israel's promise to worship Yahweh alone, Yahweh makes promises to David and to Israel – to David, the promise that his line will rule Israel forever, to Israel, the promise of the land they will possess.

- Apostasy: the great tragedy of Israel's history, meaning the destruction of the kingdom and the Temple, is due to the failure of the people, but more especially the kings, to worship Yahweh alone (Yahweh being the God of Israel).

- Judgement: Apostasy leads to judgement. Judgement is not punishment, but simply the natural (or rather, God-ordained) consequence of Israel's failure to worship Yahweh alone.

Another and related theme is that of prophecy. The main point of the prophetic stories is that God's prophecies are always fulfilled, so that any not yet fulfilled will be so in the future. The implication, the release of Jehoiachin and his restoration to a place of honour in Babylon in the closing scenes of the book, is that the promise of an eternal Davidic dynasty is still in effect, and that the Davidic line will be restored.[22]

Textual features

Chronology

The standard Hebrew text of Kings presents an impossible chronology.[23] To take just a single example, Omri's accession to the throne of Israel is dated to the 31st year of Asa of Judah[24] meanwhile the ascension of his predecessor, Zimri, who reigned for only a week, is dated to the 27th year of Asa.[25][26] The Greek text corrects the impossibilities but does not seem to represent an earlier version.[27] A large number of scholars have claimed to solve the difficulties, but the results differ, sometimes widely, and none has achieved consensus status.[28]

Kings and 2 Chronicles

The second Book of Chronicles covers much the same time-period as the books of Kings, but it ignores the northern Kingdom of Israel almost completely, David is given a major role in planning the Temple, Hezekiah is given a much more far-reaching program of reform, and Manasseh of Judah is given an opportunity to repent of his sins, apparently to account for his long reign.[29] It is usually assumed that the author of Chronicles used Kings as a source and emphasised different areas as he would have liked it to have been interpreted.[29]

See also

- Historicity of the Bible

- Kingdom of Israel (united monarchy)

- Kings of Israel and Judah

References

- Sweeney, p. 1

- Fretheim, p. 7

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2016-12-01). 1 & 2 Kings: An Introduction and Study Guide: History and Story in Ancient Israel (1 ed.). T&T Clark. ASIN B01MTO6I34.

- 2 Kings 18:3

- 2 Kings 25:27–30

- Tomes, p. 246.

- "Third and Fourth Books of Kings called in our days as First and Second of Kings", Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. 8, Wiki source, 1913.

- Bible (Douay Rheims ed.), DRBO.

- Spieckermann, p. 337.

- Perdue, xxvii.

- Wilson, p. 85.

- Sweeney, p. 4.

- Van Seters, p. 307.

- McKenzie, pp. 281–84.

- Trebolle, Julio (January 1, 1992). "LIGHT FROM 4Qjudg AND 4QKgs ON THE TEXT OF JUDGES AND KINGS". The Dead Sea Scrolls: 315–324. doi:10.1163/9789004350113_028. ISBN 9789004350113 – via brill.com.

- "Qumran Fragments of the Books of Kings | orion-editor.dev". orion-bibliography.huji.ac.il.

- "5Q2 / 5QKgs | orion-editor.dev". orion-bibliography.huji.ac.il.

- "Scholars search for pages of ancient Hebrew Bible". Los Angeles Times. September 28, 2008.

- Nelson, pp. 1–2

- Sutherland, p. 489

- Fretheim, pp. 10–14

- Sutherland, p. 490

- Sweeney, p. 43

- 1 Kings 16:23

- 1 Kings 16:15

- Sweeney, pp. 43–44

- Nelson, p. 44

- Moore & Kelle, pp. 269–71

- Sutherland, p. 147

Bibliography

Commentaries on Kings

- Fretheim, Terence E (1997). First and Second Kings. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-25565-7.

- Nelson, Richard Donald (1987). First and Second Kings. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22084-6.

- Sweeney, Marvin (2007). I & II Kings: A Commentary. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22084-6.

General

- Knight, Douglas A (1995). "Deuteronomy and the Deuteronomists". In Mays, James Luther; Petersen, David L.; Richards, Kent Harold (eds.). Old Testament Interpretation. T&T Clark. ISBN 978-0-567-29289-6.

- Knight, Douglas A (1991). "Sources". In Mills, Watson E.; Bullard, Roger Aubrey (eds.). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Mercer University Press. ISBN 978-0-86554-373-7.

- Leuchter, Mark; Adam, Klaus-Peter (2010). "Introduction". In Leuchter, Mark; Adam, Klaus-Peter; Adam, Karl-Peter (eds.). Soundings in Kings: Perspectives and Methods in Contemporary Scholarship. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-1-4514-1263-5.

- Moore, Megan Bishop; Kelle, Brad E (2011). Biblical History and Israel's Past: The Changing Study of the Bible and History. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-6260-0.

- McKenzie, Steven L (1994). "The Books of Kings". In McKenzie, Steven L.; Patrick Graham, Matt (eds.). The History of Israel's Traditions: The Heritage of Martin Noth. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-567-23035-5.

- Perdue, Leo G (2001). "Preface: The Hebrew Bible in Current Research". In Perdue, Leo G. (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to the Hebrew Bible. Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-21071-9.

- Spieckerman, Hermann (2001). "The Deuteronomistic History". In Perdue, Leo G. (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to the Hebrew Bible. Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-21071-9.

- Sutherland, Ray (1991). "Kings, Books of, First and Second". In Mills, Watson E.; Bullard, Roger Aubrey (eds.). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Mercer University Press. ISBN 978-0-86554-373-7.

- Tomes, Roger (2003). "1 and 2 Kings". In Dunn, James D.G.; Rogerson, John William (eds.). Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-3711-0.

- Van Seters, John (1997). In search of history: historiography in the ancient world and the origins of biblical history. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-013-2.

- Walton, John H. (2009). "The Deuteronomistic History". In Hill, Andrew E.; Walton, John H. (eds.). A Survey of the Old Testament. Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-22903-2.

- Wilson, Robert R (1995). "The Former Prophets: Reading the Books of Kings". In Mays, James Luther; Petersen, David L.; Harold Richards, Kent (eds.). Old Testament Interpretation: Past, Present and Future: Essays in honor of Gene M. Tucker. Continuum International. ISBN 978-0-567-29289-6.

External links

Original text

- מלכים א Melachim Aleph – Kings A (Hebrew – English at Mechon-Mamre.org)

- מלכים ב Melachim Bet – Kings B (Hebrew – English at Mechon-Mamre.org)

Jewish translations

- 1 Kings at Mechon-Mamre (Jewish Publication Society 1917 translation)

- 2 Kings at Mechon-Mamre (Jewish Publication Society 1917 translation)

Other links

- "books of Kings." Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- Cook, Stanley Arthur (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 810–815.

- Books of Kings article (Jewish Encyclopedia)

- 1 & 2 Kings: introduction Archived 2015-09-06 at the Wayback MachineForward Movement

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.