Book of Jeremiah

The Book of Jeremiah (Hebrew: ספר יִרְמְיָהוּ) is the second of the Latter Prophets in the Hebrew Bible, and the second of the Prophets in the Christian Old Testament.[1] The superscription at chapter Jeremiah 1:1–3 identifies the book as "the words of Jeremiah son of Hilkiah".[1] Of all the prophets, Jeremiah comes through most clearly as a person, ruminating to his scribe Baruch about his role as a servant of God with little good news for his audience.[2]

| |||||

| Tanakh (Judaism) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Old Testament (Christianity) | |||||

|

|

|||||

| Bible portal | |||||

His book is intended as a message to the Jews in exile in Babylon, explaining the disaster of exile as God's response to Israel's pagan worship:[3] the people, says Jeremiah, are like an unfaithful wife and rebellious children, their infidelity and rebelliousness made judgment inevitable, although restoration and a new covenant are foreshadowed.[4] Authentic oracles of Jeremiah are probably to be found in the poetic sections of chapters 1 –25, but the book as a whole has been heavily edited and added to by the prophet's followers (including, perhaps, his companion, the scribe Baruch) and later generations of Deuteronomists.[5]

It has come down in two distinct though related versions, one in Hebrew, the other known from a Greek translation.[6] The date of the two (Greek and Hebrew) can be suggested by the fact that the Greek shows concerns typical of the early Persian period, while the Masoretic (i.e., Hebrew) shows perspectives which, although known in the Persian period, did not reach their realisation until the 2nd century BCE.[7]

Structure

- (Taken from Michael D. Coogan's A Brief Introduction to the Old Testament; other sources will give slightly different divisions)

It is difficult to discern any structure in Jeremiah, probably because the book had such a long and complex composition history.[2] It can be divided into roughly six sections:[8]

- Chapters 1–25 (The earliest and main core of Jeremiah's message)

- Chapters 26–29 (Biographic material and interaction with other prophets)

- Chapters 30–33 (God's promise of restoration including Jeremiah's "new covenant" which is interpreted differently in Judaism than it is in Christianity)

- Chapters 34–45 (Mostly interaction with Zedekiah and the fall of Jerusalem)

- Chapters 46–51 (Divine punishment to the nations surrounding Israel)

- Chapter 52 (Appendix that retells 2 Kings)[9]

Summary

Historical background

The background to Jeremiah is briefly described in the superscription to the book: Jeremiah began his prophetic mission in the thirteenth year of king Josiah (about 627 BC) and finished in the eleventh year of king Zedekiah (586 BC), "when Jerusalem went into exile in the sixth month." During this period, Josiah changed the Judahite religion, Babylon destroyed Assyria, Egypt briefly imposed vassal status on Judah, Babylon defeated Egypt and made Judah a Babylonian vassal (605 BC), Judah revolted but was subjugated again by Babylon (597 BC), and Judah revolted once more.[10]

This revolt was the final one: Babylon destroyed Jerusalem and its Temple and exiled its king and many of the leading citizens in 586 BC, ending Judah's existence as an independent or quasi-independent kingdom and inaugurating the Babylonian exile.[10]

Overview

The book can be conveniently divided into biographical, prose and poetic strands, each of which can be summarised separately. The biographical material is to be found in chapters 26–29, 32, and 34–44, and focuses on the events leading up to and surrounding the fall of Jerusalem to the Babylonians in 587 BCE; it provides precise dates for the prophet's activities beginning in 609 BCE. The non-biographical prose passages, such as the Temple sermon in chapter 7 and the covenant passage in 11:1–17, are scattered throughout the book; they show clear affinities with the Deuteronomists, the school of writers and editors who shaped the series of history books from Judges to Kings, and while it is unlikely they come directly from Jeremiah, they may well have their roots in traditions about what he said and did.[11]

The poetic material is found largely in chapters 1–25 and consists of oracles in which the prophet speaks as God's messenger. These passages, dealing with Israel's unfaithfulness to God, the call to repentance, and attacks on the religious and political establishment, are mostly undated and have no clear context, but it is widely accepted that they represent the teachings of Jeremiah and are the earliest stage of the book. Allied to them, and also probably a reflection of the authentic Jeremiah, are further poetic passages of a more personal nature, which have been called Jeremiah's confessions or spiritual diary. In these poems the prophet agonises over the apparent failure of his mission, is consumed by bitterness at those who oppose or ignore him, and accuses God of betraying him.[11]

Composition

.jpg.webp)

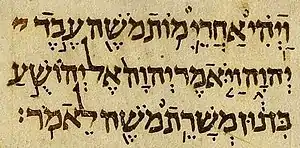

Texts and manuscripts

Jeremiah exists in two versions: a Greek translation, called the Septuagint, dating from the last few centuries BCE and found in the earliest Christian manuscripts, and the Masoretic Hebrew text of traditional Jewish bibles – the Greek version is shorter than the Hebrew by about one eighth, and arranges the material differently. Equivalents of both versions were found among the Dead Sea Scrolls, so that is clear that the differences mark important stages in the transmission of the text.[12]

Most scholars hold that the Hebrew text underlying the Septuagint version is older than the Masoretic text, and that the Masoretic evolved either from this or from a closely related version.[13][14] The shorter version ultimately became canonical in Greek Orthodox churches, while the longer was adopted in Judaism and in Western Christian churches.[15]

Composition history

It is generally agreed that the three types of material interspersed through the book – poetic, narrative, and biographical – come from different sources or circles.[16] Authentic oracles of Jeremiah are probably to be found in the poetic sections of chapters 1 –25, but the book as a whole has been heavily edited and added to by followers (including perhaps the prophet's companion, the scribe Baruch) and later generations of Deuteronomists.[5] The date of the final versions of the book (Greek and Hebrew) can be suggested by the fact that the Greek shows concerns typical of the early Persian period, while the Masoretic (i.e., Hebrew) shows perspectives which, although known in the Persian period, did not reach their realisation until the 2nd century BCE.[7]

Literary development

The Book of Jeremiah grew over a long period of time. The Greek stage, looking forward to the fall of Babylon and aligning in places with Second Isaiah, had already seen major redaction (editing) in terms of overall structure, the superscriptions (sentences identifying following passages as the words of God or of Jeremiah), the assignment of historical settings, and arrangement of material, and may have been completed by the late Exilic period (last half of the 6th century BCE); the initial stages of the Masoretic Hebrew version may have been written not long afterwards, although chapter 33:14–26[17] points to a setting in post-exilic times.[18]

Jeremiah

According to its opening verses the book records the prophetic utterances of the priest Jeremiah son of Hilkiah, "to whom the word of YHWH came in the days of king Josiah" and after. Jeremiah lived during a turbulent period, the final years of the kingdom of Judah, from the death of king Josiah (609 BCE) and the loss of independence that followed, through the destruction of Jerusalem by the Babylonians and the exile of much its population (587/586).[19] The book depicts a remarkably introspective prophet, impetuous and often angered by the role into which he has been thrust, alternating efforts to warn the people with pleas to God for mercy, until he is ordered to "pray no more for this people." He engages in extensive performance art, walking about in the streets with a yoke about his neck and engaging in other efforts to attract attention. He is taunted and retaliates, is thrown in jail as the result, and at one point is thrown into a pit to die.

Jeremiah and the Deuteronomists

The Deuteronomists were a school or movement who edited the books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings into a more or less unified history of Israel (the so-called Deuteronomistic History) during the Jewish exile in Babylon (6th century BCE).[20] It is argued that the Deuteronomists played an important role in the production of the book of Jeremiah; for example, there is clear Deuteronomistic language in chapter 25, in which the prophet looks back over twenty-three years of unheeded prophecy. From the Deuteronomistic perspective the prophetic role implied, more than anything else, concern with law and covenant after the manner of Moses. On this reading Jeremiah was the last of a long line of prophets sent to warn Israel of the consequences of infidelity to God; unlike the Deuteronomists, for whom the call for repentance was always central, Jeremiah seems at some point in his career to have decided that further intercession was pointless, and that Israel's fate was sealed.[21]

Jeremiah as a new Moses

The book's superscription claims that Jeremiah was active for forty years, from the thirteenth year of Josiah (627 BCE) to the fall of Jerusalem in 587. It is clear from the last chapters of the book, however, that he continued to speak in Egypt after the assassination of Gedaliah, the Babylonian-appointed governor of Judah, in 582. This suggests that the superscription is trying to make a theological point about Jeremiah by comparing him to Moses – whereas Moses spent forty years leading Israel from slavery in Egypt to the Promised Land, Jeremiah's forty years saw Israel exiled from the land and Jeremiah himself ultimately in exile in Egypt.[22]

Themes

Covenant

Much of Jeremiah's prophetic preaching is based on the theme of the covenant between God and Israel (God would protect the people in return for their exclusive worship of him): Jeremiah insists that the covenant is conditional, and can be broken by Israel's apostasy (worship of gods other than Yahweh, the God of Israel). The people, says Jeremiah, are like an unfaithful wife and rebellious children: their infidelity and rebelliousness makes judgement inevitable. Interspersed with this are references to repentance and renewal, although it is unclear whether Jeremiah thought that repentance could ward off judgement or whether it would have to follow judgement. The theme of restoration is strongest in chapter 31:32, which looks to a future in which a new covenant made with Israel and Judah, one which will not be broken.[4] This is the theme of the "new covenant" passage at chapter 31:31–34, drawing on Israel's past relationship with God through the covenant at Sinai to foresee a new future in which Israel will be obedient to God.[23]

The "Confessions" of Jeremiah

Scholars from Heinrich Ewald onwards [24] have identified several passages in Jeremiah which can be understood as "confessions": they occur in the first section of the book (chapters 1–25) and are generally identified as Jeremiah 11:18–12.6, 15:10–21, 17:14–18, 18:18–23, and 20:7–18.[25][26] In these five passages, Jeremiah expresses his discontent with the message he is to deliver, but also his steadfast commitment to the divine call despite the fact that he had not sought it out. Additionally, in several of these "confessions", Jeremiah prays that the Lord will take revenge on his persecutors (for example, Jeremiah 12:3[27]).[28]

Jeremiah's "confessions" are a type of individual lament. Such laments are found elsewhere in the psalms and the Book of Job. Like Job, Jeremiah curses the day of his birth (Jeremiah 20:14–18 and Job 3:3–10).[29] Likewise, Jeremiah's exclamation "For I hear the whispering of many: Terror is all around!" [30] matches Psalm 31:13[31] exactly. However, Jeremiah's laments are made unique by his insistence that he has been called by Yahweh to deliver his messages.[28] These laments "provide a unique look at the prophet's inner struggle with faith, persecution, and human suffering".[32]

Prophetic gestures

Prophetic gestures, also known as sign-acts or symbolic actions, were a form of communication in which a message was delivered by performing symbolic actions.[28] Not unique to the book of Jeremiah, these were often bizarre and violated the cultural norms of the time.[33] They served the purposes of both drawing an audience and causing that audience to ask questions, giving the prophet an opportunity to explain the meaning of the behavior. The recorder of the events in the written text (i.e. the author of the text) had neither the same audience nor, potentially, the same intent that Jeremiah had in performing these prophetic gestures.[34]

The following is a list – not exhaustive – of noteworthy sign-acts found in Jeremiah:[35]

- Jeremiah 13:1–11: The wearing, burial, and retrieval of a linen waistband.[36]

- Jeremiah 16:1–9: The shunning of the expected customs of marriage, mourning, and general celebration.[37]

- Jeremiah 19:1–13: the acquisition of a clay jug and the breaking of the jug in front of the religious leaders of Jerusalem.[38]

- Jeremiah 27–28: The wearing of an oxen yoke and its subsequent breaking by a false prophet, Hananiah.

- Jeremiah 32:6–15: The purchase of a field in Anathoth for the price of seventeen silver shekels.[39]

- Jeremiah 35:1–19: The offering of wine to the Rechabites, a tribe known for living in tents and refusing to drink wine.[40]

Later interpretation and influence

Judaism

The influence of Jeremiah during and after the Exile was considerable in some circles, and three additional books, the Book of Baruch, Lamentations, and the Letter of Jeremiah, were attributed to him in Second Temple Judaism (Judaism in the period between the building of the Second Temple in about 515 BCE and its destruction in 70 CE); in the Greek Septuagint they stand between Jeremiah and the Book of Ezekiel, but only Lamentations is included in modern Jewish or Protestant bibles (the Letter of Jeremiah appears in Catholic bibles as the sixth chapter of Baruch).[41] Jeremiah is mentioned by name in Chronicles and the Book of Ezra, both dating from the later Persian period, and his prophecy that the Babylonian exile would last 70 years was taken up and reapplied by the author of the Book of Daniel in the 2nd century BCE.

Christianity

The understanding of the early Christians that Jesus represented a "new covenant"[42] is based on Jeremiah 31:31–34, in which a future Israel will repent and give God the obedience he demands.[23] The Gospel's portrayal of Jesus as a persecuted prophet owes a great deal to the account of Jeremiah's sufferings in chapters 37–44, as well as to the "Songs of the Suffering Servant" in Isaiah.[43]

See also

- Nebo-Sarsekim Tablet

Citations

- Sweeney 1998, pp. 81–82.

- Kugler & Hartin 2009, p. 241.

- Allen 2008, pp. 7, 14.

- Biddle 2007, p. 1074.

- Coogan 2008, p. 300.

- Sweeney 1998, p. 82.

- Sweeney 2010, p. 94.

- Coogan 2008, p. 299.

- 24:18–25:30

- Brettler 2010, p. 173.

- Davidson 1993, pp. 345–46.

- Blenkinsopp 1996, p. 130.

- Williamson 2009, p. 168.

- The Oxford Handbook of the Prophets, Oxford University Press, 2016, edited Carolyn Sharp, author Marvin A Sweeney, p. 456

- Allen 2008, pp. 7–8.

- Davidson 1993, p. 345.

- 33:14–26

- Allen 2008, p. 11.

- Sweeney 2010, p. 86.

- Knight 1995, pp. 65–66.

- Blenkinsopp 1996, pp. 132, 135–36.

- Sweeney 2010, pp. 87–88.

- Davidson 1993, p. 347.

- Ewald, Heinrich, Die Propheten des Alten Bundes, II: Jeremja und Hezeqiel mit ihren Zeitgenossen, first edition 1840, 2nd edition; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1868. (Commentary on the Prophets of the Old Testament, III: Nahum SSephanya, Habaqquq, 'Zakharja' XII.-XIV., Yeremja, translated by J. Frederick Smith; London: Williams & Norgate, 1878)

- Jeremiah 11:18–12.6, 15:10–21, 17:14–18, 18:18–23, and 20:7–18

- Diamond identifies several other passages also described as "confessions": see Diamond, A. R. (1987), The Confessions of Jeremiah in Context, JSOTSup 45, Sheffield, p. 193

- Jeremiah 12:3

- Coogan 2008, p. 303.

- Jeremiah 20:14–18 and Job 3:3–10

- Jeremiah 20:10

- Psalm 31:13

- Perdue 2006, p. 1021.

- e.g. Ezekiel 4:4–8

- Friebel 1999, p. 13.

- Friebel 1999, pp. 88–136.

- Jeremiah 13:1–11

- Jeremiah 16:1–9

- Jeremiah 19:1–13

- Jeremiah 32:6–15

- Jeremiah 35:1–19

- Redditt 2008, pp. 132–33.

- see 1 Corinthians 11:25 and Hebrews 8:6–13

- Blenkinsopp 1996, p. 134.

Bibliography

- Allen, Leslie C. (2008). Jeremiah: A Commentary. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664222239.

- Arena, Francesco (September 2020). Lemche, Niels Peter (ed.). "False Prophets in the Book of Jeremiah: Did They All Prophesy and Speak Falsehood?". Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament. Taylor & Francis. 34 (2): 187–200. doi:10.1080/09018328.2020.1807104. ISSN 1502-7244. S2CID 221866227.

- Bandstra, Barry L. (2004). Reading the Old Testament: an introduction to the Hebrew Bible. Wadsworth. ISBN 9780495391050.

- Biddle, Mark E. (2007). "Jeremiah". In Coogan, Michael D.; Brettler, Mark Zvi; Newsom, Carol Ann (eds.). The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books: New Revised Standard Version. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199743919.

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (1996). A history of prophecy in Israel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664256395.

- Brettler, Marc Zvi (2010). How to read the Bible. Jewish Publication Society. ISBN 978-0-8276-0775-0.

- Brueggemann, Walter (2002). Reverberations of faith: a theological handbook of Old Testament themes. Westminster John Knox. ISBN 9780664222314.

- Coogan, Michael D. (2008). A Brief Introduction to the Old Testament: The Hebrew Bible in Its Context. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195332728.

- Davidson, Robert (1993). "Jeremiah, Book of". In Metzger, Bruce M.; Coogan, Michael D. (eds.). The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199743919.

- Diamond, A. R. Pete (2003). "Jeremiah". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William (eds.). Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Friebel, Kelvin G. (1999). Jeremiah's and Ezekiel's Sign-Acts: Rhetorical Nonverbal Communication. Continuum. ISBN 9781850759195.

- Knight, Douglas A. (1995). "Deuteronomy and the Deuteronomists". In Mays, James Luther; Petersen, David L.; Richards, Harold (eds.). Old Testament Interpretation. T&T Clark. ISBN 9780567292896.

- Kugler, Robert; Hartin, Patrick (2009). The Old Testament between theology and history: a critical survey. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802846365.

- Perdue, Leo G. (2006). "Jeremiah". In Attridge, Harold W. (ed.). HarperCollins Study Bible. HarperCollins.

- Redditt, Paul L. (2008). Introduction to the Prophets. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802828965.

- Sweeney, Marvin A. (2010). The Prophetic Literature. Abingdon Press. ISBN 9781426730030.

- Sweeney, Marvin A. (1998). "The Latter Prophets". In Steven L. McKenzie, Matt Patrick Graham (ed.). The Hebrew Bible today: an introduction to critical issues. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664256524.

- Williamson, H. G. M. (2009). "Do We Need A New Bible? Reflections on the Proposed Oxford Hebrew Bible". Biblia. BSW. 90: 168. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

External links

- Hebrew text:

- Translations into English

- Jewish translations:

- Jeremiah at Mechon-Mamre (Jewish Publication Society translation)

- Christian translations:

- Online Bible at GospelHall.org

- Jeremiah at The Great Books (New Revised Standard Version) (via archive.org)

Bible: Jeremiah public domain audiobook at LibriVox Various versions

Bible: Jeremiah public domain audiobook at LibriVox Various versions

- Jewish translations:

- Wikisource texts

- Book of Jeremiah (Hebrew)

- Septuagint (Greek)

- Vulgate (Latin)

- Wycliffe / King James / American Standard / World English Bible (English)