Cricket World Cup

The Cricket World Cup (officially known as ICC Men's Cricket World Cup)[2] is the international championship of One Day International (ODI) cricket. The event is organised by the sport's governing body, the International Cricket Council (ICC), every four years, with preliminary qualification rounds leading up to a finals tournament. The tournament is one of the world's most viewed sporting events and is considered the "flagship event of the international cricket calendar" by the ICC.[3]

Cricket World Cup Trophy | |

| Administrator | International Cricket Council (ICC) |

|---|---|

| Format | One Day International |

| First edition | 1975 |

| Latest edition | 2019 |

| Next edition | 2023 |

| Tournament format | ↓various |

| Number of teams | 20 (all tournaments) 10 (current) 14 (2027 onwards)[1] |

| Current champion | |

| Most successful | |

| Most runs | |

| Most wickets | |

| Website | www.cricketworldcup.com |

| Tournaments | |

|---|---|

|

The first World Cup was organised in England in June 1975, with the first ODI cricket match having been played only four years earlier. However, a separate Women's Cricket World Cup had been held two years before the first men's tournament, and a tournament involving multiple international teams had been held as early as 1912, when a triangular tournament of Test matches was played between Australia, England and South Africa. The first three World Cups were held in England. From the 1987 tournament onwards, hosting has been shared between countries under an unofficial rotation system, with fourteen ICC members having hosted at least one match in the tournament.

The current format involves a qualification phase, which takes place over the preceding three years, to determine which teams qualify for the tournament phase. In the tournament phase, 10 teams, including the automatically qualifying host nation, compete for the title at venues within the host nation over about a month. In the 2027 edition, the format will be changed to accommodate an expanded 14-team final competition.[4]

A total of twenty teams have competed in the eleven editions of the tournament, with ten teams competing in the recent 2019 tournament. Australia has won the tournament five times, India and West Indies twice each, while Pakistan, Sri Lanka and England have won it once each. The best performance by a non-full-member team came when Kenya made the semi-finals of the 2003 tournament.

England are the current champions after winning the 2019 World Cup edition. The next tournament will be held in India in 2023 and the subsequent 2027 World Cup will be held jointly in South Africa, Zimbabwe and Namibia

History

The first international cricket match was played between Canada and the United States, on 24 and 25 September 1844.[5] However, the first credited Test match was played in 1877 between Australia and England, and the two teams competed regularly for The Ashes in subsequent years. South Africa was admitted to Test status in 1889.[6] Representative cricket teams were selected to tour each other, resulting in bilateral competition. Cricket was also included as an Olympic sport at the 1900 Paris Games, where Great Britain defeated France to win the gold medal.[7] This was the only appearance of cricket at the Summer Olympics.[8]

The first multilateral competition at international level was the 1912 Triangular Tournament, a Test cricket tournament played in England between all three Test-playing nations at the time: England, Australia and South Africa. The event was not a success: the summer was exceptionally wet, making play difficult on damp uncovered pitches, and crowd attendances were poor, attributed to a "surfeit of cricket".[9] Since then, international Test cricket has generally been organised as bilateral series: a multilateral Test tournament was not organised again until the triangular Asian Test Championship in 1999.[10]

The number of nations playing Test cricket increased gradually over time, with the addition of West Indies in 1928, New Zealand in 1930, India in 1932, and Pakistan in 1952. However, international cricket continued to be played as bilateral Test matches over three, four or five days.

In the early 1960s, English county cricket teams began playing a shortened version of cricket which only lasted for one day. Starting in 1962 with a four-team knockout competition known as the Midlands Knock-Out Cup,[11] and continuing with the inaugural Gillette Cup in 1963, one-day cricket grew in popularity in England. A national Sunday League was formed in 1969. The first One-Day International match was played on the fifth day of a rain-aborted Test match between England and Australia at Melbourne in 1971, to fill the time available and as compensation for the frustrated crowd. It was a forty over game with eight balls per over.[12]

In the late 1970s, Kerry Packer established the rival World Series Cricket (WSC) competition. It introduced many of the now commonplace features of One Day International cricket, including coloured uniforms, matches played at night under floodlights with a white ball and dark sight screens, and, for television broadcasts, multiple camera angles, effects microphones to capture sounds from the players on the pitch, and on-screen graphics. The first of the matches with coloured uniforms was the WSC Australians in wattle gold versus WSC West Indians in coral pink, played at VFL Park in Melbourne on 17 January 1979. The success and popularity of the domestic one-day competitions in England and other parts of the world, as well as the early One-Day Internationals, prompted the ICC to consider organising a Cricket World Cup.[13]

Prudential World Cups (1975–1983)

The inaugural Cricket World Cup was hosted in 1975 by England, the only nation able to put forward the resources to stage an event of such magnitude at the time. The 1975 tournament started on 7 June.[14] The first three events were held in England and officially known as the Prudential Cup after the sponsors Prudential plc. The matches consisted of 60 six-ball overs per team, played during the daytime in traditional form, with the players wearing cricket whites and using red cricket balls.[15]

Eight teams participated in the first tournament: Australia, England, India, New Zealand, Pakistan, and the West Indies (the six Test nations at the time), together with Sri Lanka and a composite team from East Africa.[16] One notable omission was South Africa, who were banned from international cricket due to apartheid. The tournament was won by the West Indies, who defeated Australia by 17 runs in the final at Lord's.[16] Roy Fredricks of West Indies was the first batsmen who got hit-wicket in ODI during the 1975 World Cup final.[17]

The 1979 World Cup saw the introduction of the ICC Trophy competition to select non-Test playing teams for the World Cup,[18] with Sri Lanka and Canada qualifying.[19] The West Indies won a second consecutive World Cup tournament, defeating the hosts England by 92 runs in the final. At a meeting which followed the World Cup, the International Cricket Conference agreed to make the competition a quadrennial event.[19]

The 1983 event was hosted by England for a third consecutive time. By this stage, Sri Lanka had become a Test-playing nation, and Zimbabwe qualified through the ICC Trophy. A fielding circle was introduced, 30 yards (27 m) away from the stumps. Four fieldsmen needed to be inside it at all times.[20] The teams faced each other twice, before moving into the knock-outs. India was crowned champions after upsetting the West Indies by 43 runs in the final.[13][21]

Different champions (1987–1996)

India and Pakistan jointly hosted the 1987 tournament, the first time that the competition was held outside England. The games were reduced from 60 to 50 overs per innings, the current standard, because of the shorter daylight hours in the Indian subcontinent compared with England's summer.[22] Australia won the championship by defeating England by 7 runs in the final, the closest margin in the World Cup final until the 2019 edition between England and New Zealand.[23][24]

The 1992 World Cup, held in Australia and New Zealand, introduced many changes to the game, such as coloured clothing, white balls, day/night matches, and a change to the fielding restriction rules. The South African cricket team participated in the event for the first time, following the fall of the apartheid regime and the end of the international sports boycott.[25] Pakistan overcame a dismal start in the tournament to eventually defeat England by 22 runs in the final and emerge as winners.[26]

The 1996 championship was held in the Indian subcontinent for a second time, with the inclusion of Sri Lanka as host for some of its group stage matches.[27] In the semi-final, Sri Lanka, heading towards a crushing victory over India at Eden Gardens after the hosts lost eight wickets while scoring 120 runs in pursuit of 252, were awarded victory by default after crowd unrest broke out in protest against the Indian performance.[28] Sri Lanka went on to win their maiden championship by defeating Australia by seven wickets in the final at Lahore.[29]

Australian treble (1999–2007)

In 1999 the event was hosted by England, with some matches also being held in Scotland, Ireland, Wales and the Netherlands.[30][31] Twelve teams contested the World Cup. Australia qualified for the semi-finals after reaching their target in their Super 6 match against South Africa off the final over of the match.[32] They then proceeded to the final with a tied match in the semi-final also against South Africa where a mix-up between South African batsmen Lance Klusener and Allan Donald saw Donald drop his bat and stranded mid-pitch to be run out. In the final, Australia dismissed Pakistan for 132 and then reached the target in less than 20 overs and with eight wickets in hand.[33]

South Africa, Zimbabwe and Kenya hosted the 2003 World Cup. The number of teams participating in the event increased from twelve to fourteen. Kenya's victories over Sri Lanka and Zimbabwe, among others – and a forfeit by the New Zealand team, which refused to play in Kenya because of security concerns – enabled Kenya to reach the semi-finals, the best result by an associate.[34] In the final, Australia made 359 runs for the loss of two wickets, the largest ever total in a final, defeating India by 125 runs.[35][36]

In 2007 the tournament was hosted by the West Indies and expanded to sixteen teams.[37] Following Pakistan's upset loss to World Cup debutants Ireland in the group stage, Pakistani coach Bob Woolmer was found dead in his hotel room.[38] Jamaican police had initially launched a murder investigation into Woolmer's death but later confirmed that he died of heart failure.[39] Australia defeated Sri Lanka in the final by 53 runs (D/L) in farcical light conditions, and extended their undefeated run in the World Cup to 29 matches and winning three straight championships.[40]

Hosts triumph (2011–2019)

India, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh together hosted the 2011 World Cup. Pakistan were stripped of their hosting rights following the terrorist attack on the Sri Lankan cricket team in 2009, with the games originally scheduled for Pakistan redistributed to the other host countries.[41] The number of teams participating in the World Cup was reduced to fourteen.[42] Australia lost their final group stage match against Pakistan on 19 March 2011, ending an unbeaten streak of 35 World Cup matches, which had begun on 23 May 1999.[43] India won their second World Cup title by beating Sri Lanka by 6 wickets in the final at Wankhede Stadium in Mumbai, making India became the first country to win the World Cup at home.[42] This was also the first time that two Asian countries faced each other in a World Cup Final.[44]

Australia and New Zealand jointly hosted the 2015 World Cup. The number of participants remained at fourteen. Ireland was the most successful Associate nation with a total of three wins in the tournament. New Zealand beat South Africa in a thrilling first semi-final to qualify for their maiden World Cup final. Australia defeated New Zealand by seven wickets in the final at Melbourne to lift the World Cup for the fifth time.[45]

The 2019 World Cup was hosted by England and Wales. The number of participants was reduced to 10. New Zealand defeated India in the first semi-final, which was pushed over to the reserve day due to rain.[46] England defeated the defending champions, Australia, in the second semi-final. Neither finalist had previously won the World Cup. In the final, the scores were tied at 241 after 50 overs and the match went to a super over, after which the scores were again tied at 15. The World Cup was won by England, whose boundary count was greater than New Zealand's.[47][48]

Format

Qualification

From the first World Cup in 1975 up to the 2019 World Cup, the majority of teams taking part qualified automatically. Until the 2015 World Cup this was mostly through having Full Membership of the ICC, and for the 2019 World Cup this was mostly through ranking position in the ICC ODI Championship.[49]

Since the second World Cup in 1979 up to the 2019 World Cup, the teams that qualified automatically were joined by a small number of others who qualified for the World Cup through the qualification process. The first qualifying tournament being the ICC Trophy;[50] later the process expanding with pre-qualifying tournaments. For the 2011 World Cup, the ICC World Cricket League replaced the past pre-qualifying processes; and the name "ICC Trophy" was changed to "ICC World Cup Qualifier".[51] The World Cricket League was the qualification system provided to allow the Associate and Affiliate members of the ICC more opportunities to qualify. The number of teams qualifying varied throughout the years.

From the 2023 World Cup onwards, only the host nation(s) will qualify automatically. All countries will participate in a series of leagues to determine qualification, with automatic promotion and relegation between divisions from one World Cup cycle to the next.[52]

Tournament

The format of the Cricket World Cup has changed greatly over the course of its history. Each of the first four tournaments was played by eight teams, divided into two groups of four.[53] The competition consisted of two stages, a group stage and a knock-out stage. The four teams in each group played each other in the round-robin group stage, with the top two teams in each group progressing to the semi-finals. The winners of the semi-finals played against each other in the final. With South Africa returning in the fifth tournament in 1992 as a result of the end of the apartheid boycott, nine teams played each other once in the group phase, and the top four teams progressed to the semi-finals.[54] The tournament was further expanded in 1996, with two groups of six teams.[55] The top four teams from each group progressed to quarter-finals and semi-finals.

A distinct format was used for the 1999 and 2003 World Cups. The teams were split into two pools, with the top three teams in each pool advancing to the Super 6.[56] The Super 6 teams played the three other teams that advanced from the other group. As they advanced, the teams carried their points forward from previous matches against other teams advancing alongside them, giving them an incentive to perform well in the group stages.[56] The top four teams from the Super 6 stage progressed to the semi-finals, with the winners playing in the final.

The format used in the 2007 World Cup involved 16 teams allocated into four groups of four.[57] Within each group, the teams played each other in a round-robin format. Teams earned points for wins and half-points for ties. The top two teams from each group moved forward to the Super 8 round. The Super 8 teams played the other six teams that progressed from the different groups. Teams earned points in the same way as the group stage, but carried their points forward from previous matches against the other teams who qualified from the same group to the Super 8 stage.[58] The top four teams from the Super 8 round advanced to the semi-finals, and the winners of the semi-finals played in the final.

The format used in the 2011 and 2015[59] World Cups featured two groups of seven teams, each playing in a round-robin format. The top four teams from each group proceeded to the knock out stage consisting of quarter-finals, semi-finals and ultimately the final.[60]

In the 2019 World Cup, the number of teams participating dropped to 10. Each team was scheduled to play against each other once in a round robin format, before entering the semifinals,[61] a similar format to the 1992 World Cup. The 2027 and 2031 World Cups will have 14 teams.[62]

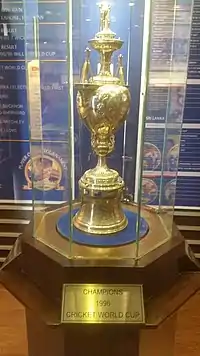

Trophy

The ICC Cricket World Cup Trophy is presented to the winners of the World Cup. The current trophy was created for the 1999 championships, and was the first permanent prize in the tournament's history. Prior to this, different trophies were made for each World Cup.[63] The trophy was designed and produced in London by a team of craftsmen from Garrard & Co over a period of two months.[64][65]

The current trophy is made from silver and gilt, and features a golden globe held up by three silver columns. The columns, shaped as stumps and bails, represent the three fundamental aspects of cricket: batting, bowling and fielding, while the globe characterises a cricket ball.[66] The seam is tilted to symbolize the axial tilt of the Earth. It stands 60 centimetres high and weighs approximately 11 kilograms. The names of the previous winners are engraved on the base of the trophy, with space for a total of twenty inscriptions. The ICC keeps the original trophy. A replica differing only in the inscriptions is permanently awarded to the winning team.[67]

Media coverage

The tournament is one of the world's most-viewed sporting events,[68][69] and successive tournaments have generated increasing media attention as One-Day International cricket has become more established. The 2011 Cricket World Cup was televised in over 200 countries to over 2.2 billion viewers.[64][70] Television rights, mainly for the 2011 and 2015 World Cup, were sold for over US$1.1 billion,[71] and sponsorship rights were sold for a further US$500 million.[72] On 13 February, the opening of the 2015 tournament was celebrated with a Google Doodle.[73] The ICC claimed a total of 1.6 billion viewers for the 2019 World Cup as well as 4.6 billion views of digital video of the tournament.[74] The most-watched match of the tournament was the group game between India and Pakistan, which was watched by more than 300 million people live.[75]

Attendance

The 2003 Cricket World Cup matches were attended by 626,845 people,[76] while the 2007 Cricket World Cup sold more than 672,000 tickets.[77][78] A total attendance of 12,29,826 spectators for the 2011 Cricket World Cup. In 2015 Cricket World Cup total attendance was 1,016,420. A total attendance of 752,000 spectators was reported for the 2019 Cricket World Cup tournament.

Selection of hosts

The International Cricket Council's executive committee votes for the hosts of the tournament after examining the bids made by the nations keen to hold a Cricket World Cup.[79]

.svg.png.webp)

1979,1983,

1999,2019

1996,2011,

2023,2031

England hosted the first three competitions. The ICC decided that England should host the first tournament because it was ready to devote the resources required to organising the inaugural event.[14] India volunteered to host the third Cricket World Cup, but most ICC members preferred England as the longer period of daylight in England in June meant that a match could be completed in one day.[80] The 1987 Cricket World Cup was held in India and Pakistan, the first hosted outside England.[81]

Many of the tournaments have been jointly hosted by nations from the same geographical region, such as South Asia in 1987, 1996 and 2011, Australasia (in Australia and New Zealand) in 1992 and 2015, Southern Africa in 2003 and West Indies in 2007.

In November 2021, ICC published the name of the hosts for ICC events to be played between 2024 and 2031 cycle. The hosts for the 50-over World Cup along with T20 World Cup and Champions Trophy were selected through a competitive bidding process.[82][83]

Results

| Year | Official Host(s) | Final | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Venue | Winners | Result | Runners-up | ||

| 1975 | Lord's, London | 291/8 (60 overs) |

West Indies won by 17 runs Scorecard |

274 all out (58.4 overs) | |

| 1979 | Lord's, London | 286/9 (60 overs) |

West Indies won by 92 runs Scorecard |

194 all out (51 overs) | |

| 1983 | Lord's, London | 183 all out (54.4 overs) |

India won by 43 runs Scorecard |

140 all out (52 overs) | |

| 1987 | Eden Gardens, Kolkata | 253/5 (50 overs) |

Australia won by 7 runs Scorecard |

246/8 (50 overs) | |

| 1992 | Melbourne Cricket Ground, Melbourne | 249/6 (50 overs) |

Pakistan won by 22 runs Scorecard |

227 all out (49.2 overs) | |

| 1996 | Gaddafi Stadium, Lahore | 245/3 (46.2 overs) |

Sri Lanka won by 7 wickets Scorecard |

241/7 (50 overs) | |

| 1999 | Lord's, London | 133/2 (20.1 overs) |

Australia won by 8 wickets Scorecard |

132 all out (39 overs) | |

| 2003 | Wanderers Stadium, Johannesburg | 359/2 (50 overs) |

Australia won by 125 runs Scorecard |

234 all out (39.2 overs) | |

| 2007 | Kensington Oval, Bridgetown | 281/4 (38 overs) |

Australia won by 53 runs (D/L) Scorecard |

215/8 (36 overs) | |

| 2011 | Wankhede Stadium, Mumbai | 277/4 (48.2 overs) |

India won by 6 wickets Scorecard |

274/6 (50 overs) | |

| 2015 | Melbourne Cricket Ground, Melbourne | 186/3 (33.1 overs) |

Australia won by 7 wickets Scorecard |

183 all out (45 overs) | |

| 2019 | Lord's, London | 241 all out (50 overs) 15/0 (super over) 23 fours, 3 sixes |

England won on boundary count after super over Scorecard |

241/8 (50 overs) 15/1 (super over) 14 fours, 3 sixes | |

| 2023 | TBD | ||||

| 2027 | TBD | ||||

| 2031 | TBD | ||||

- Notes

- The England and Wales Cricket Board was the sole designated host, but matches were also played in Ireland, the Netherlands, and Scotland.

- Cricket South Africa was the sole designated host, but matches were also played in Zimbabwe and Kenya.

- Eight member countries of the West Indies Cricket Board hosted matches – Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, and Trinidad and Tobago.

Tournament Summary

Twenty nations have qualified for the Cricket World Cup at least once. Seven teams have competed in every tournament, six of which have won the title.[13] The West Indies won the first two tournaments, Australia has won five, India has won two, while Pakistan, Sri Lanka and England have each won once. The West Indies (1975 and 1979) and Australia (1987, 1999, 2003, 2007 and 2015) are the only teams to have won consecutive titles.[13] Australia has played in seven of the twelve finals (1975, 1987, 1996, 1999, 2003, 2007 and 2015). New Zealand has yet to win the World Cup, but has been runners-up two times (2015 and 2019). The best result by a non-Test playing nation is the semi-final appearance by Kenya in the 2003 tournament; while the best result by a non-Test playing team on their debut is the Super 8 (second round) by Ireland in 2007.[13]

Sri Lanka, as a co-host of the 1996 World Cup, was the first host to win the tournament, though the final was held in Pakistan.[13] India won in 2011 as host and was the first team to win a final played in their own country.[84] Australia and England repeated the feat in 2015 and 2019 respectively.[45] Other than this, England made it to the final as a host in 1979. Other countries which have achieved or equalled their best World Cup results while co-hosting the tournament are New Zealand as finalists in 2015, Zimbabwe who reached the Super Six in 2003, and Kenya as semi-finalists in 2003.[13] In 1987, co-hosts India and Pakistan both reached the semi-finals, but were eliminated by England and Australia respectively.[13] Australia in 1992, England in 1999, South Africa in 2003, and Bangladesh in 2011 have been host teams that were eliminated in the first round.[85]

Teams' performances

An overview of the teams' performances in every World Cup is given below. For each tournament, the number of teams in each finals tournament (in brackets) are shown.

Host Team |

1975 (8) |

1979 (8) |

1983 (8) |

1987 (8) |

1992 (9) |

1996 (12) |

1999 (12) |

2003 (14) |

2007 (16) |

2011 (14) |

2015 (14) |

2019 (10) |

2023 (10) |

2027 (14) |

2031 (14) |

Apps. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GP | GP | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| RU | GP | GP | W | GP | RU | W | W | W | QF | W | SF | 12 | ||||

| GP | GP | S8 | GP | QF | GP | Q | 6 | |||||||||

| GP | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| GP | GP | GP | GP | 4 | ||||||||||||

| GP | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| SF | RU | SF | RU | RU | QF | GP | GP | S8 | QF | GP | W | 12 | ||||

| GP | GP | W | SF | GP | SF | S6 | RU | GP | W | SF | SF | Q | Q | 12 | ||

| S8 | GP | GP | 3 | |||||||||||||

| GP | GP | SF | GP | GP | 5 | |||||||||||

| GP | Q | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| GP | GP | GP | GP | 4 | ||||||||||||

| SF | SF | GP | GP | SF | QF | SF | S6 | SF | SF | RU | RU | 12 | ||||

| GP | SF | SF | SF | W | QF | RU | GP | GP | SF | QF | GP | 12 | ||||

| GP | GP | GP | 3 | |||||||||||||

| SF | QF | SF | GP | SF | QF | SF | GP | Q | 8 | |||||||

| GP | GP | GP | GP | GP | W | GP | SF | RU | RU | QF | GP | 12 | ||||

| GP | GP | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| W | W | RU | GP | GP | SF | GP | GP | S8 | QF | QF | GP | 12 | ||||

| GP | GP | GP | GP | S6 | S6 | GP | GP | GP | Q | 9 |

Legend

- W – Winner

- RU– Runner up

- SF– Semi-finals

- QF– Quarter-finals (1996, 2011–2015)

- S6– Super Six (1999–2003)

- S8– Super Eight (2007)

- GP – Group stage / First round

- Q – Qualified, still in contention

Debutant teams

| Year | Teams |

|---|---|

| 1975 | |

| 1979 | |

| 1983 | |

| 1987 | none |

| 1992 | |

| 1996 | |

| 1999 | |

| 2003 | |

| 2007 | |

| 2011 | none |

| 2015 | |

| 2019 | none |

| 2023 | TBD |

| 2027 | TBD |

| 2031 | TBD |

Overview

The table below provides an overview of the performances of teams over past World Cups, as of the end of the 2019 tournament. Teams are sorted by best performance, then by appearances, total number of wins, total number of games, and alphabetical order respectively.

| Appearances | Best performance | Statistics | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Team | Total | First | Latest | Mat. | Won | Lost | Tie | NR | Win%* | |

| 12 | 1975 | 2019 | Champions (1987, 1999, 2003, 2007, 2015) | 94 | 69 | 23 | 1 | 1 | 74.73 | |

| 12 | 1975 | 2019 | Champions (1983, 2011) | 84 | 53 | 29 | 1 | 1 | 64.45 | |

| 12 | 1975 | 2019 | Champions (1975, 1979) | 80 | 43 | 35 | 0 | 2 | 55.12 | |

| 12 | 1975 | 2019 | Champions (2019) | 83 | 48 | 32 | 2 | 1 | 59.75 | |

| 12 | 1975 | 2019 | Champions (1992) | 79 | 45 | 32 | 0 | 2 | 58.44 | |

| 12 | 1975 | 2019 | Champions (1996) | 80 | 38 | 39 | 1 | 2 | 49.35 | |

| 12 | 1975 | 2019 | Runners-up (2015, 2019) | 89 | 54 | 33 | 1 | 1 | 61.93 | |

| 8 | 1992 | 2019 | Semi-finals (1992, 1999, 2007, 2015) | 64 | 38 | 23 | 2 | 1 | 61.90 | |

| 5 | 1996 | 2011 | Semi-finals (2003) | 29 | 7 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 24.13 | |

| 9 | 1983 | 2015 | Super 6s (1999, 2003) | 57 | 11 | 42 | 1 | 3 | 21.29 | |

| 6 | 1999 | 2019 | Quarter-finals (2015), Super 8s (2007) | 40 | 14 | 25 | 0 | 1 | 35.89 | |

| 3 | 2007 | 2015 | Super 8s (2007) | 21 | 7 | 13 | 1 | 0 | 35.71 | |

| 4 | 1996 | 2011 | Group Stage (1996, 2003, 2007, 2011) | 20 | 2 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 10.00 | |

| 4 | 1979 | 2011 | Group Stage (1979, 2003, 2007, 2011) | 18 | 2 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 11.11 | |

| 3 | 1999 | 2015 | Group Stage (1999, 2007, 2015) | 14 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| 2 | 2015 | 2019 | Group Stage (2015, 2019) | 15 | 1 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 6.66 | |

| 2 | 1996 | 2015 | Group Stage (1996, 2015) | 11 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 9.09 | |

| 1 | 2003 | 2003 | Group Stage (2003) | 6 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| 1 | 2007 | 2007 | Group Stage (2007) | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Defunct teams | ||||||||||

| 1 | 1975 | 1975 | Group Stage (1975) | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Last Updated: 14 July 2019 Source: ESPNcricinfo | ||||||||||

Note:

- The Win percentage excludes no results and counts ties as half a win.

- Teams are sorted by their best performance, then winning percentage, then (if equal) by alphabetical order.

- Disbanded in 1989

- Before the 1992 World Cup, South Africa were banned due to apartheid

Awards

Man of the tournament

Since 1992, one player has been declared as the "Man of the Tournament" at the end of the World Cup finals.[86]

| Year | Player | Performance details |

|---|---|---|

| 1992 | 456 runs | |

| 1996 | 221 runs and 7 wickets | |

| 1999 | 281 runs and 17 wickets | |

| 2003 | 673 runs and 2 wickets | |

| 2007 | 26 wickets | |

| 2011 | 362 runs and 15 wickets | |

| 2015 | 22 wickets | |

| 2019 | 578 runs and 2 wickets |

Man of the Match in the Final

There were no Man of the Tournament awards before 1992 but Man of the Match awards have always been given for individual matches. As of the 2019 tournament, the award has always made to a member of the winning side. The Man of the Match of the finals of the competition have been:[86]

| Year | Player | Performance details |

|---|---|---|

| 1975 | 102 | |

| 1979 | 138* | |

| 1983 | 3/12 and 26 | |

| 1987 | 75 | |

| 1992 | 33 and 3/49 | |

| 1996 | 107* and 3/42 | |

| 1999 | 4/33 | |

| 2003 | 140* | |

| 2007 | 149 | |

| 2011 | 91* | |

| 2015 | 3/36 | |

| 2019 | 84* and 0/20 |

Tournament records

| World Cup records[87] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Batting | ||

| Most runs | 2,278 (1992–2011) | |

| Highest average (min. 10 inns.) [88] | 124.00 (1999–2003) | |

| Highest score | 237* (2015) | |

| Highest partnership | (2nd wicket) v |

372 (2015) |

| Most runs in a single world cup | 673 (2003) | |

| Most hundreds | 6 (2015–2019) 6 (1992–2011) | |

| Most hundreds in a single world cup | 5 (2019) | |

| Bowling | ||

| Most wickets | 71 (1996–2007) | |

| Lowest average (min. 400 balls bowled) | 14.81 (2015–2019) | |

| Best strike rate (min. 20 wickets) | 18.6 (2015–2019) | |

| Best economy rate (min. 1000 balls bowled) | 3.24 (1975–1983) | |

| Best bowling figures | 7/15 (2003) | |

| Most wickets in a tournament | 27 (2019) | |

| Fielding | ||

| Most dismissals (wicket-keeper) | 54 (2003–2015) | |

| Most catches (fielder) | 28 (1996–2011) | |

| Team | ||

| Highest score | 417/6 (2015) | |

| Lowest score | 36 (2003) | |

| Highest win % | 74.73% (Played 94, Won 69)[89] | |

| Most consecutive wins | 27 (20 Jun 1999 – 19 Mar 2011, one N/R excluded)[90] | |

| Most consecutive tournament wins | 3 (1999–2007) | |

See also

- ICC Under-19 Cricket World Cup

- ICC T20 World Cup

- ICC Champions Trophy

- Women's Cricket World Cup

References

- "ICC announces expansion of global events". ICC. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- "ICC Men's Cricket World Cup 2019 shatters audience records". ICC. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ICC Cricket World Cup: About Archived 1 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine – International Cricket Council. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- "The road to World Cup 2023: how teams can secure qualification, from rank No. 1 to 32". ESPN Cricinfo. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- Martin Williamson. "The oldest international contest of them all". ESPN. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- "1st Test Scorecard". ESPNcricinfo. 15 March 1877. Archived from the original on 12 February 2009. Retrieved 28 January 2007.

- "Olympic Games, 1900, Final". ESPNcricinfo. 19 August 1900. Archived from the original on 26 December 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2006.

- Purohit, Abhishek (10 August 2021). "Will Cricket Bat Again at the Olympics? Know Process for Inclusion at LA28". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- "The original damp squib". ESPNcricinfo. 23 April 2005. Archived from the original on 16 October 2007. Retrieved 29 August 2006.

- "The run-out that sparked a riot". ESPNcricinfo. 30 October 2010. Archived from the original on 22 October 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- "The low-key birth of one-day cricket". ESPNcricinfo. 9 April 2011. Archived from the original on 19 September 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- "What is One-Day International cricket?". newicc.cricket.org. Archived from the original on 19 November 2006. Retrieved 10 September 2006.

- "The World Cup – A brief history". ESPNcricinfo. Archived from the original on 28 March 2008. Retrieved 7 December 2006.

- "The History of World Cup's". cricworld.com. Archived from the original on 13 March 2007. Retrieved 19 September 2006.

- Browning (1999), pp. 5–9

- Browning (1999), pp. 26–31

- "50 fascinating facts about World Cups – Part 1". Cricbuzz. Archived from the original on 21 February 2019. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- "ICC Trophy – A brief history". ESPNcricinfo. Archived from the original on 26 November 2006. Retrieved 29 August 2006.

- Browning (1999), pp. 32–35

- Browning (1999), pp. 61–62

- Browning (1999), pp. 105–110

- Browning (1999), pp. 111–116

- Browning (1999), pp. 155–159

- "Cricket World Cup 2003". A.Srinivas. Archived from the original on 2 October 2008. Retrieved 28 January 2007.

- Browning (1999), pp. 160–161

- Browning (1999), pp. 211–214

- Browning (1999), pp. 215–217

- "1996 Semi-final scoreboard". cricketfundas. Archived from the original on 7 November 2006. Retrieved 28 January 2007.

- Browning (1999), pp. 264–274

- Browning (1999), p. 274

- French Toast (2014). Cricket World Cup: A Summary of the Tournaments Since 1975 (e-book). Smashwords. ISBN 9781311429230. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- Browning (1999), pp. 229–231

- Browning (1999), pp. 232–238

- "Washouts, walkovers, and black armband protests". ESPNcricinfo. Archived from the original on 30 August 2015. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- "Ruthless Aussies lift World Cup". London: BBC. 23 March 2003. Archived from the original on 28 March 2015. Retrieved 29 January 2007.

- "Full tournament schedule". London: BBC. 23 March 2003. Archived from the original on 18 February 2007. Retrieved 22 February 2007.

- "Australia triumph in a tournament to forget". ESPNcricinfo. Archived from the original on 6 February 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- "Bob Woolmer's death stuns cricket world". ESPNcricinfo. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- "Bob Woolmer investigation round-up". Cricinfo. Archived from the original on 16 May 2007. Retrieved 6 May 2007.

- "Australia v Sri Lanka, World Cup final, Barbados". Cricinfo. 28 April 2007. Archived from the original on 24 March 2008. Retrieved 6 May 2007.

- "No World Cup matches in Pakistan". BBC. 18 April 2009. Archived from the original on 18 April 2009. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- "India end a 28-year-long wait". ESPNcricinfo. Archived from the original on 25 August 2013. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- "Pakistan top group after ending Australia's unbeaten World Cup streak". CNN. 20 March 2011. Archived from the original on 13 February 2015. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- "ICC Cricket World Cup". ESPN. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- "Cricket World Cup 2015: Australia crush New Zealand in final". BBC Sport. 29 March 2015. Archived from the original on 29 March 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "India vs New Zealand Highlights, World Cup 2019 semi-final: Match defers to reserve day". Times of India. 9 July 2019. Archived from the original on 11 July 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- "Epic final tied, Super Over tied,England win World Cup on boundary count". Archived from the original on 15 July 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- Fordyce, Tom (14 July 2019). "England win Cricket World Cup: A golden hour ends in a champagne super over". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 14 July 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- "Cricket World Cup 2019 to stay at only 10 teams". BBC. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- Cricinfo – 2005 ICC Trophy in Ireland

- "World Cricket League". ICC. Archived from the original on 19 January 2007. Retrieved 28 January 2007.

- "The road to World Cup 2023: how teams can secure qualification, from rank No. 1 to 32". ESPN Cricinfo. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- "1st tournament". icc.cricket.org. Archived from the original on 17 December 2007. Retrieved 19 February 2007.

- "92 tournament". icc.cricket.org. Archived from the original on 17 December 2007. Retrieved 19 February 2007.

- "96 tournament". icc.cricket.org. Archived from the original on 17 December 2007. Retrieved 19 February 2007.

- "Super 6". Cricinfo. Archived from the original on 22 February 2007. Retrieved 19 February 2007.

- "World Cup groups". cricket world cup. Archived from the original on 26 January 2007. Retrieved 28 January 2007.

- "About the Event" (PDF). cricketworldcup.com. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 September 2006. Retrieved 2 September 2006.

- "2015 Cricket World Cup". cricknews.net. Archived from the original on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- Nayar, K.R. (29 June 2011). "International Cricket Council approves 14-team cup". Gulf News. Archived from the original on 1 July 2011. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- Smale, Simon (4 June 2019). "The Cricket World Cup 2019 has shrunk to exclude the minnows, but why? And how come it's still so long?". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- "ICC announces World Cup schedule; 14 teams in 2027 And 2031". Six Sports. 2 June 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- "Trophy is first permanent prize in Cricket World Cup". cricket-worldcup2015.net. Archived from the original on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 9 November 2007.

- "More money, more viewers and fewer runs in prospect for intriguing World Cup". The Guardian. 12 February 2015. Archived from the original on 4 March 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- "Trophies | Famous Trophies". Garrard. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- "Cricket World Cup- Past Glimpses". webindia123.com. Archived from the original on 23 March 2008. Retrieved 31 October 2007.

- "About the Tournament". International Cricket Council. Archived from the original on 25 June 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- "Cricket World Cup 2015 3rd Most Watched Sports Event In The World". Total Sportek. 11 January 2015. Archived from the original on 25 March 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- Baker, Alison (25 July 2022). "The Most Watched Sporting Events in The World". www.roadtrips.com. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- "World Cup Overview". cricketworldcup.com. Archived from the original on 24 January 2007. Retrieved 29 January 2007.

- Cricinfo staff (9 December 2006). "ICC rights for to ESPN-star". Cricinfo. Archived from the original on 1 February 2009. Retrieved 30 January 2007.

- Cricinfo staff (18 January 2006). "ICC set to cash in on sponsorship rights". Cricinfo. Archived from the original on 1 February 2009. Retrieved 30 January 2007.

- "Google release Doodle to mark the start of the 2015 Cricket World Cup". The Independent. 13 February 2015. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- "ICC Men's Cricket World Cup gives GDP 350 million boost to UK economy". www.icc-cricket.com. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- "2019 Men's Cricket World Cup most watched ever". www.icc-cricket.com. 16 September 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- "Cricket World Cup 2003" (PDF). ICC. p. 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 March 2006. Retrieved 29 January 2007.

- "World Cup profits boost debt-ridden Windies board". Content-usa.cricinfo.com. Archived from the original on 24 March 2008. Retrieved 24 June 2012.

- "ICC CWC 2007 Match Attendance Soars Past 400,000". cricketworld.com. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 25 April 2007.

- "Asia to host 2011 World Cup". Cricinfo. 30 April 2006. Archived from the original on 28 September 2012. Retrieved 9 February 2007.

- "The 1979 World Cup in England – West Indies retain their title". Cricinfo. Archived from the original on 23 May 2006. Retrieved 19 September 2006.

- "The 1987 World Cup in India and Pakistan – Australia win tight tournament". Cricinfo. Archived from the original on 16 July 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- "India to host three ICC events in 2024-31 cycle". Cricbuzz. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- "USA to stage T20 World Cup: 2024-2031 ICC Men's tournament hosts confirmed". www.icc-cricket.com. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- "India power past Sri Lanka to Cricket World Cup triumph". BBC Sport. 2 April 2011. Archived from the original on 3 April 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- Sportstar, Team (24 May 2019). "World Cup, 11 editions: How host countries fared". sportstar.thehindu.com. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- "Cricket World Cup Past Glimpses". webindia123.com. Archived from the original on 23 March 2008. Retrieved 31 October 2007.

- All records are based on statistics at Cricinfo.com's list of World Cup records Archived 3 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "Best Average in Cricket World Cup". ESPN Cricinfo. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- "World Cup Cricket Team Records & Stats". ESPNCricinfo. Archived from the original on 27 February 2011. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- "Statistics / Statsguru / One-Day Internationals / Team records". Cricinfo. Archived from the original on 11 September 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

Sources

- Browning, Mark (1999). A complete history of World Cup Cricket. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7318-0833-9.

_2017.svg.png.webp)