Antarctic Circle

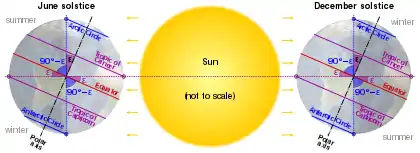

The Antarctic Circle is the most southerly of the five major circles of latitude that mark maps of Earth. The region south of this circle is known as the Antarctic, and the zone immediately to the north is called the Southern Temperate Zone. South of the Antarctic Circle, the Sun is above the horizon for 24 continuous hours at least once per year (and therefore visible at midnight) and the centre of the Sun (ignoring refraction) is below the horizon for 24 continuous hours at least once per year (and therefore not visible at noon); this is also true within the equivalent polar circle in the Northern Hemisphere, the Arctic Circle.

The position of the Antarctic Circle is not fixed and currently runs 66°33′49.2″ south of the Equator.[1] This figure may be slightly inaccurate because it does not allow for the effects of astronomical nutation, which can be up to 10″. Its latitude depends on the Earth's axial tilt, which fluctuates within a margin of more than 2° over a 41,000-year period, due to tidal forces resulting from the orbit of the Moon.[2] Consequently, the Antarctic Circle is currently drifting southwards at a speed of about 14.5 m (48 ft) per year.

Midnight sun and polar night

The Antarctic Circle is the northernmost latitude in the Southern Hemisphere at which the centre of the sun can remain continuously above the horizon for twenty-four hours; as a result, at least once each year at any location within the Antarctic Circle the centre of the sun is visible at local midnight, and at least once the centre of the sun is below the horizon at local noon.[3][4]

Directly on the Antarctic Circle these events occur, in principle, exactly once per year: at the December and June solstices, respectively. However, because of atmospheric refraction and mirages, and because the sun appears as a disk and not a point, part of the midnight sun may be seen on the night of the southern summer solstice up to about 50 minutes (′) (90 km (56 mi)) north of the Antarctic Circle; similarly, on the day of the southern winter solstice, part of the sun may be seen up to about 50′ south of the Antarctic Circle. That is true at sea level; those limits increase with elevation above sea level, although in mountainous regions there is often no direct view of the true horizon. Mirages on the Antarctic continent tend to be even more spectacular than in Arctic regions, creating, for example, a series of apparent sunsets and sunrises while in reality the sun remains below the horizon.

Human habitation

There is no permanent human population south of the Antarctic Circle, but there are several research stations in Antarctica operated by various nations that are inhabited by teams of scientists who rotate on a seasonal basis. In previous centuries some semi-permanent whaling stations were established on the continent, and some whalers would live there for a year or more. At least three children have been born in Antarctica, albeit in stations north of the Antarctic Circle.

Geography

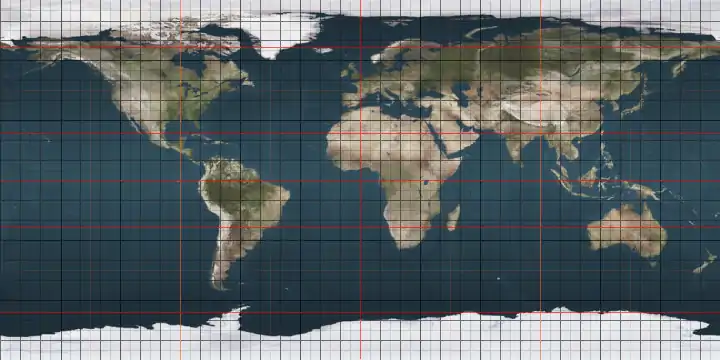

The circumference of the Antarctic Circle is roughly 16,000 kilometres (9,900 mi).[5] The area south of the Circle is about 20,000,000 km2 (7,700,000 sq mi) and covers roughly 4% of Earth's surface.[6] Most of the continent of Antarctica is within the Antarctic Circle.

Sites along the Circle

Starting at the prime meridian and heading eastwards, the Antarctic Circle passes through:

See also

- Antarctic Convergence

- Tropic of Cancer

- Tropic of Capricorn

References

- "Obliquity of the Ecliptic (Eps Mean)". Neoprogrammics.com. Retrieved 2014-05-13.

- Berger, A.L. (1976). "Obliquity and Precession for the Last 5000000 Years". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 51 (1): 127–135. Bibcode:1976A&A....51..127B.

- Burn, Chris. The Polar Night (PDF). The Aurora Research Institute. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- NB: This refers to the true geometric centre which actually appears higher in the sky because of refraction by the atmosphere.

- Nuttall, Mark (2004). Encyclopedia of the Arctic Volumes 1, 2 and 3. Routledge. p. 115. ISBN 978-1579584368. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- William M. Marsh; Martin M. Kaufman (2012). Physical Geography: Great Systems and Global Environments. Cambridge University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-521-76428-5.