Armenians

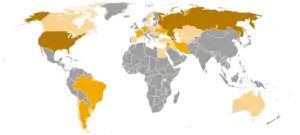

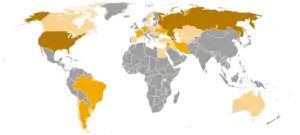

Armenians (Armenian: հայեր, hayer [hɑˈjɛɾ]) are an ethnic group native to the Armenian highlands of Western Asia.[34] Armenians constitute the main population of Armenia and the de facto independent Artsakh. There is a wide-ranging diaspora of around five million people of full or partial Armenian ancestry living outside modern Armenia. The largest Armenian populations today exist in Russia, the United States, France, Georgia, Iran, Germany, Ukraine, Lebanon, Brazil, and Syria. With the exceptions of Iran and the former Soviet states, the present-day Armenian diaspora was formed mainly as a result of the Armenian genocide.[35]

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

c. 8 million[1] to 11–16 million[2]

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 1,182,388[5]–2,900,000[6] | |

| 1,000,366[7]–1,500,000[8] | |

| 250,000[9]–750,000[10] | |

• | 168,191[11] 41,864[12] |

• | 146,573[13] |

| 150,000[14] | |

| 120,000[15] | |

| 90,000–110,000[16] | |

| 100,000[17] | |

| 100,000[18] | |

| 100,000[19][20] | |

| 80,000[21] | |

| 70,000[22] | |

| 60,000–300,000 / 100,000–5,000,000 (Hidden Armenians)[23] | |

| 55,740[24] | |

| 50,000-70,000[25] | |

| 50,000[26] | |

| 40,000[27] | |

| 40,000[28] | |

| 25,000[29] | |

| 22,526[30] | |

| 8,000–10,000[31] | |

| 5,689[n]–8,374[m] (2021)[32][33] | |

| Languages | |

| Armenian | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity Armenian Apostolic Church · Catholic · Protestant Armenian Native Faith | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Hemshin, Cherkesogai, Hayhurum, Armeno-Tats, Hidden Armenians | |

^ n: by legal nationality ^ m: by nationality, naturalisation and descendant background | |

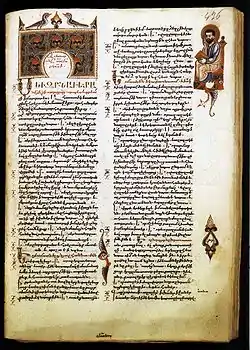

Armenian is an Indo-European language.[36] It has two mutually intelligible spoken and written forms: Eastern Armenian, today spoken mainly in Armenia, Artsakh, Iran, and the former Soviet republics; and Western Armenian, used in the historical Western Armenia and, after the Armenian genocide, primarily in the Armenian diasporan communities. The unique Armenian alphabet was invented in 405 AD by Mesrop Mashtots.

Most Armenians adhere to the Armenian Apostolic Church, a non-Chalcedonian Christian church, which is also the world's oldest national church. Christianity began to spread in Armenia soon after Jesus' death, due to the efforts of two of his apostles, St. Thaddeus and St. Bartholomew.[37] In the early 4th century, the Kingdom of Armenia became the first state to adopt Christianity as a state religion.[38]

Etymology

The earliest attestations of the exonym Armenia date around the 6th century BC. In his trilingual Behistun Inscription dated to 517 BC, Darius I the Great of Persia refers to Urashtu (in Babylonian) as Armina (Old Persian: 𐎠𐎼𐎷𐎡𐎴) and Harminuya (in Elamite). In Greek, Armenios (Αρμένιοι) is attested from about the same time, perhaps the earliest reference being a fragment attributed to Hecataeus of Miletus (476 BC).[39] Xenophon, a Greek general serving in some of the Persian expeditions, describes many aspects of Armenian village life and hospitality in around 401 BC.

Some have linked the name Armenia with the Early Bronze Age state of Armani (Armanum, Armi) or the Late Bronze Age state of Arme (Shupria).[40] Armini, Urartian for "inhabitant of Arme" or "Armean country," referring to the region of Shupria, to the immediate west of Lake Van.[41] The Arme tribe of Urartian texts may have been the Urumu, who in the 12th century BC attempted to invade Assyria from the north with their allies the Mushki and the Kaskians. The Urumu apparently settled in the vicinity of Sason, lending their name to the regions of Arme and the nearby lands of Urme and Inner Urumu.[42] The location of the older site of Armani is a matter of debate. Some modern researchers have placed it in the same general area as Arme, near modern Samsat,[43] and have suggested it was populated, at least partially, by an early Indo-European-speaking people.[44] The relationship between Armani and the later Arme-Shupria, if any, is undetermined. Additionally, their connections to Armenians is inconclusive as it is not known what languages were spoken in these regions.

It has also been speculated that the land of Ermenen (located in or near Minni), mentioned by the Egyptian pharaoh Thutmose III in 1446 BCE, could be a reference to Armenia.

Armenians call themselves Hay (Armenian: հայ, pronounced [ˈhaj]; plural: հայեր, [haˈjɛɾ]). The name has traditionally been derived from Hayk (Armenian: Հայկ), the legendary patriarch of the Armenians and a great-great-grandson of Noah, who, according to Movses Khorenatsi (Moses of Khorene), defeated the Babylonian king Bel in 2492 BC and established his nation in the Ararat region.[45] It is also further postulated[46][47] that the name Hay comes from, or is related to, one of the two confederated, Hittite vassal states—Hayasa-Azzi (1600–1200 BC). Ultimately, Hay may derive from the Proto Indo-European words póti (meaning "lord" or "master")[48] or *h₂éyos/*áyos (meaning "metal").[49]

Khorenatsi wrote that the word Armenian originated from the name Armenak or Aram (the descendant of Hayk). Khorenatsi refers to both Armenia and Armenians as Hayk‘ (Armenian: Հայք) (not to be confused with the aforementioned patriarch, Hayk).

History

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

Origin

While the Armenian language is classified as an Indo-European language, its placement within the broader Indo-European language family is a matter of debate. Until fairly recently, scholars believed Armenian to be most closely related to Greek and Ancient Macedonian. Eric P. Hamp placed Armenian in the "Pontic Indo-European" (also called Graeco-Armenian or Helleno-Armenian) subgroup of Indo-European languages in his 2012 Indo-European family tree.[50] There are two possible explanations, not mutually exclusive, for a common origin of the Armenian and Greek languages.

- In Hamp's view, the homeland of the proposed Graeco-Armenian subgroup is the northeast coast of the Black Sea and its hinterlands.[50] He assumes that they migrated from there southeast through the Caucasus with the Armenians remaining after Batumi while the pre-Greeks proceeded westward along the southern coast of the Black Sea.[50]

- Ancient Greek historian Herodotus (writing circa 440 BCE), suggested that Armenians migrated from Phrygia, a region that encompassed much of western and central Anatolia during the Iron Age: "the Armenians were equipped like Phrygians, being Phrygian colonists" (7.73) (Ἀρμένιοι δὲ κατά περ Φρύγες ἐσεσάχατο, ἐόντες Φρυγῶν ἄποικοι.). This statement was interpreted by later scholars as meaning that Armenians spoke a language derived from Phrygian, a poorly attested Indo-European language. However, this theory has been discredited.[51][52] Ancient Greek writers believed that the Phrygians had originated in the Balkans, in an area adjoining Macedonia, from where they had emigrated to Anatolia during the Bronze Age collapse. This led later scholars to theorize that Armenians also originated in the Balkans. However, an Armenian origin in the Balkans, although once widely accepted, has been facing increased scrutiny in recent years due to discrepancies in the timeline and lack of genetic and archeological evidence.[50][53][54] The view that Armenians are native to the South Caucasus is supported by ancient Armenian historical accounts and legends, which place the Ararat Plain as the cradle of Armenian culture, as well as modern genetic research. In fact, some scholars have suggested that the Phrygians and/or the apparently related Mushki people were originally from Armenia and moved westward.[55]

Some linguists tentatively conclude that Armenian, Greek (and Phrygian) and Indo-Iranian were dialectally close to each other;[56][57][58][59][60][61] within this hypothetical dialect group, Proto-Armenian was situated between Proto-Greek (centum subgroup) and Proto-Indo-Iranian (satem subgroup).[62] This has led some scholars to propose a hypothetical Graeco-Armenian-Aryan clade within the Indo-European language family from which the Armenian, Greek, Indo-Iranian, and possibly Phrygian languages all descend.[63] According to Kim (2018), however, there is insufficient evidence for a cladistic connection between Armenian and Greek, and common features between these two languages can be explained as a result of contact. Contact is also the most likely explanation for morphological features shared by Armenian with Indo-Iranian and Balto-Slavic languages.[64]

It has been suggested that the Bronze Age Trialeti-Vanadzor culture and sites such as the burial complexes at Verin and Nerkin Naver are indicative of an Indo-European presence in Armenia by the end of the 3rd millennium BCE.[65][66][67][68][69][70][54] The controversial Armenian hypothesis, put forward by some scholars, such as Thomas Gamkrelidze and Vyacheslav V. Ivanov, proposes that the Indo-European homeland was around the Armenian Highland.[71] This theory was partially confirmed by the research of geneticist David Reich (et al. 2018), among others.[72][73][74] Similarly Grolle (et al. 2018) supports not only a homeland for Armenians on the Armenian highlands, but also that the Armenian highlands are the homeland for the "pre-proto-Indo-Europeans".[75] A large genetic study in 2022 showed that many Armenians are "direct patrilineal descendants of the Yamnaya".[76]

Genetic studies explain Armenian diversity by several mixtures of Eurasian populations that occurred between 3000 and 2000 BCE. But genetic signals of population mixture cease after 1200 BCE when Bronze Age civilizations in the Eastern Mediterranean world suddenly and violently collapsed. Armenians have since remained isolated and genetic structure within the population developed ~500 years ago when Armenia was divided between the Ottomans and the Safavid Empire in Iran.[77][78] A genetic study (Wang et al. 2018) supports the indigenous origin for Armenians in a region south of the Caucasus which he calls "Greater Caucasus".[79]

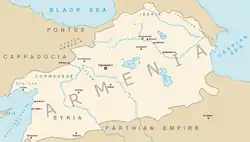

In the Bronze Age, several states flourished in the area of Greater Armenia, including the Hittite Empire (at the height of its power in the 14th century BCE), (Mitanni (South-Western historical Armenia, 1500–1300 BCE), and Hayasa-Azzi (1500–1200 BCE). Soon after Hayasa-Azzi came Arme-Shupria (1300s–1190 BCE), the Nairi Confederation (1200–900 BCE), and the Kingdom of Urartu (860–590 BCE), who successively established their sovereignty over the Armenian Highland. Each of the aforementioned nations and tribes participated in the ethnogenesis of the Armenian people.[80] Under Ashurbanipal (669–627 BCE), the Assyrian empire reached the Caucasus Mountains (modern Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan).[81]

Luwianologist John D. Hawkins proposed that "Hai" people were possibly mentioned in the 10th century BCE Hieroglyphic Luwian inscriptions from Carchemish.[82] A.E. Redgate later clarified that these "Hai" people may have been Armenians.[83]

Antiquity

The first geographical entity that was called Armenia by neighboring peoples (such as by Hecataeus of Miletus and on the Achaemenid Behistun Inscription) was the Satrapy of Armenia, established in the late 6th century BCE under the Orontid (Yervanduni) dynasty within the Achaemenid Persian Empire. The Orontids later ruled the independent Kingdom of Armenia. At its zenith (95–65 BCE), under the imperial reign of Tigran the Great, a member of the Artaxiad (Artashesian) dynasty, the Kingdom of Armenia extended from the Caucasus all the way to what is now central Turkey, Lebanon, and northern Iran.

The Arsacid Kingdom of Armenia, itself a branch of the Arsacid dynasty of Parthia, was the first state to adopt Christianity as its religion (it had formerly been adherent to Armenian paganism, which was influenced by Zoroastrianism,[84] while later on adopting a few elements regarding identification of its pantheon with Greco-Roman deities).[85] In the early years of the 4th century, likely 301 CE,[86] partly in defiance of the Sassanids it seems.[87] In the late Parthian period, Armenia was a predominantly Zoroastrian-adhering land,[84] but by the Christianisation, previously predominant Zoroastrianism and paganism in Armenia gradually declined.[87][88] Later on, in order to further strengthen Armenian national identity, Mesrop Mashtots invented the Armenian alphabet, in 405 CE. This event ushered the Golden Age of Armenia, during which many foreign books and manuscripts were translated to Armenian by Mesrop's pupils. Armenia lost its sovereignty again in 428 CE to the rivaling Byzantine and Sassanid Persian empires, until the Muslim conquest of Persia overran also the regions in which Armenians lived.

Middle Ages

In 885 CE the Armenians reestablished themselves as a sovereign kingdom under the leadership of Ashot I of the Bagratid Dynasty. A considerable portion of the Armenian nobility and peasantry fled the Byzantine occupation of Bagratid Armenia in 1045, and the subsequent invasion of the region by Seljuk Turks in 1064. They settled in large numbers in Cilicia, an Anatolian region where Armenians were already established as a minority since Roman times. In 1080, they founded an independent Armenian Principality then Kingdom of Cilicia, which became the focus of Armenian nationalism. The Armenians developed close social, cultural, military, and religious ties with nearby Crusader States,[89] but eventually succumbed to Mamluk invasions. In the next few centuries, Djenghis Khan, Timurids, and the tribal Turkic federations of the Ak Koyunlu and the Kara Koyunlu ruled over the Armenians.

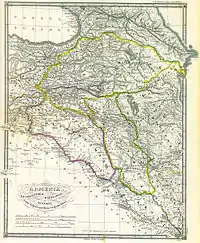

Early modern history

.jpg.webp)

From the early 16th century, both Western Armenia and Eastern Armenia fell under Iranian Safavid rule.[90][91] Owing to the century long Turco-Iranian geo-political rivalry that would last in Western Asia, significant parts of the region were frequently fought over between the two rivalling empires. From the mid 16th century with the Peace of Amasya, and decisively from the first half of the 17th century with the Treaty of Zuhab until the first half of the 19th century,[92] Eastern Armenia was ruled by the successive Iranian Safavid, Afsharid and Qajar empires, while Western Armenia remained under Ottoman rule. In the late 1820s, the parts of historic Armenia under Iranian control centering on Yerevan and Lake Sevan (all of Eastern Armenia) were incorporated into the Russian Empire following Iran's forced ceding of the territories after its loss in the Russo-Persian War (1826-1828) and the outcoming Treaty of Turkmenchay.[93] Western Armenia however, remained in Ottoman hands.

Modern history

.jpg.webp)

The ethnic cleansing of Armenians during the final years of the Ottoman Empire is widely considered a genocide, resulting in an estimated 1.5 million victims. The first wave of persecution was in the years 1894 to 1896, the second one culminating in the events of the Armenian genocide in 1915 and 1916. With World War I in progress, the Ottoman Empire accused the (Christian) Armenians as liable to ally with Imperial Russia, and used it as a pretext to deal with the entire Armenian population as an enemy within their empire.

Governments of the Republic of Turkey since that time have consistently rejected charges of genocide, typically arguing either that those Armenians who died were simply in the way of a war, or that killings of Armenians were justified by their individual or collective support for the enemies of the Ottoman Empire. Passage of legislation in various foreign countries, condemning the persecution of the Armenians as genocide, has often provoked diplomatic conflict. (See Recognition of the Armenian genocide)

Following the breakup of the Russian Empire in the aftermath of World War I for a brief period, from 1918 to 1920, Armenia was an independent republic plagued by socio-economic crises such as large-scale Muslim uprisings. In late 1920, the communists came to power following an invasion of Armenia by the Red Army; in 1922, Armenia became part of the Transcaucasian SFSR of the Soviet Union, later on forming the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic (1936 to 21 September 1991). In 1991, Armenia declared independence from the USSR and established the second Republic of Armenia.

Geographic distribution

Armenia

>50% 25–50% <25%

Armenians are believed to have had a presence in the Armenian Highland for over 4,000 years. According to legend, Hayk, the patriarch and founder of the Armenian nation, led Armenians to victory over Bel of Babylon and settled in the Armenian Highland.[94] Today, with a population of 3.5 million (although more recent estimates place the population closer to 2.9 million), they not only constitute an overwhelming majority in Armenia, but also in the disputed region of Artsakh. Armenians in the diaspora informally refer to them as Hayastantsis (Armenian: հայաստանցի), meaning those that are from Armenia (that is, those born and raised in Armenia). They, as well as the Armenians of Iran and Russia, speak the Eastern dialect of the Armenian language. The country itself is secular as a result of Soviet domination, but most of its citizens identify themselves as Apostolic Armenian Christian.

Diaspora

Small Armenian trading and religious communities have existed outside Armenia for centuries. For example, a community survived for over a millennium in the Holy Land, and one of the four-quarters of the walled Old City of Jerusalem has been called the Armenian Quarter.[95] An Armenian Catholic monastic community of 35 founded in 1717 exists on an island near Venice, Italy. There are also remnants of formerly populous communities in Turkey (Istanbul),[96] India, Myanmar, Thailand, Belgium, Portugal, Italy, Israel, Poland, Austria, Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania, Serbia, Ethiopia, Sudan and Egypt.

Regardless, most of the modern days diaspora consists of Armenians scattered throughout the world as a direct consequence of the genocide of 1915, constituting the main portion of the Armenian diaspora. However, Armenian communities in the Georgian capital city of Tbilisi, in Syria and in Iran existed since antiquity.[35]

Within the diasporan Armenian community, there is an unofficial classification of the different kinds of Armenians. For example, Armenians who originate from Iran are referred to as Parskahay (Armenian: պարսկահայ), while Armenians from Lebanon are usually referred to as Lipananahay (Armenian: լիբանանահայ). Armenians of the Diaspora are the primary speakers of the Western dialect of the Armenian language. This dialect has considerable differences with Eastern Armenian, but speakers of either of the two variations can usually understand each other. Eastern Armenian in the diaspora is primarily spoken in Iran and European countries such as Ukraine, Russia, and Georgia (where they form a majority in the Samtskhe-Javakheti province). In diverse communities (such as in Canada and the U.S.) where many different kinds of Armenians live together, there is a tendency for the different groups to cluster together.

Culture

Religion

Before Christianity, Armenians adhered to Armenian Indo-European native religion: a type of indigenous polytheism that pre-dated the Urartu period but which subsequently adopted several Greco-Roman and Iranian religious characteristics.[97][98]

In 301 AD, Armenia adopted Christianity as a state religion, becoming the first state to do so.[37] The claim is primarily based on the fifth-century work of Agathangelos titled "The History of the Armenians." Agathangelos witnessed at first hand the baptism of the Armenian King Trdat III (c. 301/314 A.D.) by St. Gregory the Illuminator.[99] Trdat III decreed Christianity was the state religion.[100]

Armenia established a Church that still exists independently of both the Catholic and the Eastern Orthodox churches, having become so in 451 AD as a result of its stance regarding the Council of Chalcedon.[37] Today this church is known as the Armenian Apostolic Church, which is a part of the Oriental Orthodox communion, not to be confused with the Eastern Orthodox communion. During its later political eclipses, Armenia depended on the church to preserve and protect its unique identity. The original location of the Armenian Catholicosate is Echmiadzin. However, the continuous upheavals, which characterized the political scenes of Armenia, made the political power move to safer places. The Church center moved as well to different locations together with the political authority. Therefore, it eventually moved to Cilicia as the Holy See of Cilicia.[101]

.jpg.webp)

Armenia has, at times, constituted a Christian "island" in a mostly Muslim region. There are, however, a minority of ethnic Armenian Muslims, known as Hamshenis and Crypto-Armenians, although the former are often regarded as a distinct group or subgroup. In the late tsarist Caucasus, individual conversions of Muslims, Yazidis, Jews, and Assyrians into Armenian Christianity have been documented.[102] The history of the Jews in Armenia dates back over 2,000 years. The Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia had close ties to European Crusader States. Later on, the deteriorating situation in the region led the bishops of Armenia to elect a Catholicos in Etchmiadzin, the original seat of the Catholicosate. In 1441, a new Catholicos was elected in Etchmiadzin in the person of Kirakos Virapetsi, while Krikor Moussapegiants preserved his title as Catholicos of Cilicia. Therefore, since 1441, there have been two Catholicosates in the Armenian Church with equal rights and privileges, and with their respective jurisdictions. The primacy of honor of the Catholicosate of Etchmiadzin has always been recognized by the Catholicosate of Cilicia.[103]

While the Armenian Apostolic Church remains the most prominent church in the Armenian community throughout the world, Armenians (especially in the diaspora) subscribe to any number of other Christian denominations. These include the Armenian Catholic Church (which follows its own liturgy but recognizes the Roman Catholic Pope), the Armenian Evangelical Church, which started as a reformation in the Mother church but later broke away, and the Armenian Brotherhood Church, which was born in the Armenian Evangelical Church, but later broke apart from it. There are other numerous Armenian churches belonging to Protestant denominations of all kinds.

Through the ages many Armenians have collectively belonged to other faiths or Christian movements, including the Paulicians which is a form of Gnostic and Manichaean Christianity. Paulicians sought to restore the pure Christianity of Paul and in c.660 founded the first congregation in Kibossa, Armenia.

Another example is the Tondrakians, who flourished in medieval Armenia between the early 9th century and 11th century. Tondrakians advocated the abolishment of the church, denied the immortality of the soul, did not believe in an afterlife, supported property rights for peasants, and equality between men and women.

The Orthodox Armenians or the Chalcedonian Armenians in the Byzantine Empire were called Iberians ("Georgians") or "Greeks". A notable Orthodox “Iberian” Armenian was the Byzantine General Gregory Pakourianos. The descendants of these Orthodox and Chalcedonic Armenians are the Hayhurum of Greece and Catholic Armenians of Georgia.

Language and literature

Armenian is a sub-branch of the Indo-European family, and with some 8 million speakers one of the smallest surviving branches, comparable to Albanian or the somewhat more widely spoken Greek, with which it may be connected (see Graeco-Armenian). Today, that branch has just one language – Armenian.

Five million Eastern Armenian speakers live in the Caucasus, Russia, and Iran, and approximately two to three million people in the rest of the Armenian diaspora speak Western Armenian. According to US Census figures, there are 300,000 Americans who speak Armenian at home. It is in fact the twentieth most commonly spoken language in the United States, having slightly fewer speakers than Haitian Creole, and slightly more than Navajo.

Armenian literature dates back to 400 AD, when Mesrop Mashtots first invented the Armenian alphabet. This period of time is often viewed as the Golden Age of Armenian literature. Early Armenian literature was written by the "father of Armenian history", Moses of Chorene, who authored The History of Armenia. The book covers the time-frame from the formation of the Armenian people to the fifth century AD. The nineteenth century beheld a great literary movement that was to give rise to modern Armenian literature. This period of time, during which Armenian culture flourished, is known as the Revival period (Zartonki sherchan). The Revivalist authors of Constantinople and Tiflis, almost identical to the Romanticists of Europe, were interested in encouraging Armenian nationalism. Most of them adopted the newly created Eastern or Western variants of the Armenian language depending on the targeted audience, and preferred them over classical Armenian (grabar). This period ended after the Hamidian massacres, when Armenians experienced turbulent times. As Armenian history of the 1920s and of the Genocide came to be more openly discussed, writers like Paruyr Sevak, Gevork Emin, Silva Kaputikyan and Hovhannes Shiraz began a new era of literature.

Architecture

The first Armenian churches were built on the orders of St. Gregory the Illuminator, and were often built on top of pagan temples, and imitated some aspects of Armenian pre-Christian architecture.[104]

Classical and Medieval Armenian Architecture is divided into four separate periods.

The first Armenian churches were built between the 4th and 7th century, beginning when Armenia converted to Christianity, and ending with the Arab invasion of Armenia. The early churches were mostly simple basilicas, but some with side apses. By the fifth century the typical cupola cone in the center had become widely used. By the seventh century, centrally planned churches had been built and a more complicated niched buttress and radiating Hrip'simé style had formed. By the time of the Arab invasion, most of what we now know as classical Armenian architecture had formed.

From the 9th to 11th century, Armenian architecture underwent a revival under the patronage of the Bagratid Dynasty with a great deal of building done in the area of Lake Van, this included both traditional styles and new innovations. Ornately carved Armenian Khachkars were developed during this time.[105] Many new cities and churches were built during this time, including a new capital at Lake Van and a new Cathedral on Akdamar Island to match. The Cathedral of Ani was also completed during this dynasty. It was during this time that the first major monasteries, such as Haghpat and Haritchavank were built. This period was ended by the Seljuk invasion.

Sports

Many types of sports are played in Armenia, among the most popular being football, chess, boxing, basketball, ice hockey, sambo, wrestling, weightlifting, and volleyball.[106] Since independence, the Armenian government has been actively rebuilding its sports program in the country.

During Soviet rule, Armenian athletes rose to prominence winning plenty of medals and helping the USSR win the medal standings at the Olympics on numerous occasions. The first medal won by an Armenian in modern Olympic history was by Hrant Shahinyan, who won two golds and two silvers in gymnastics at the 1952 Summer Olympics in Helsinki. In football, their most successful team was Yerevan's FC Ararat, which had claimed most of the Soviet championships in the 70s and had also gone to post victories against professional clubs like FC Bayern Munich in the Euro cup.

Armenians have also been successful in chess, which is the most popular mind sport in Armenia. Some of the most prominent chess players in the world are Armenian such as Tigran Petrosian, Levon Aronian and Garry Kasparov. Armenians have also been successful in weightlifting and wrestling (Armen Nazaryan), winning medals in each sport at the Olympics. There are also successful Armenians in football – Henrikh Mkhitaryan, boxing – Arthur Abraham and Vic Darchinyan.

Music and dance

Armenian music is a mix of indigenous folk music, perhaps best-represented by Djivan Gasparyan's well-known duduk music, as well as light pop, and extensive Christian music.

Instruments like the duduk, the dhol, the zurna and the kanun are commonly found in Armenian folk music. Artists such as Sayat Nova are famous due to their influence in the development of Armenian folk music. One of the oldest types of Armenian music is the Armenian chant which is the most common kind of religious music in Armenia. Many of these chants are ancient in origin, extending to pre-Christian times, while others are relatively modern, including several composed by Saint Mesrop Mashtots, the inventor of the Armenian alphabet. Whilst under Soviet rule, Armenian classical music composer Aram Khatchaturian became internationally well known for his music, for various ballets and the Sabre Dance from his composition for the ballet Gayane.

The Armenian Genocide caused widespread emigration that led to the settlement of Armenians in various countries in the world. Armenians kept to their traditions and certain diasporans rose to fame with their music. In the post-Genocide Armenian community of the United States, the so-called "kef" style Armenian dance music, using Armenian and Middle Eastern folk instruments (often electrified/amplified) and some western instruments, was popular. This style preserved the folk songs and dances of Western Armenia, and many artists also played the contemporary popular songs of Turkey and other Middle Eastern countries from which the Armenians emigrated. Richard Hagopian is perhaps the most famous artist of the traditional "kef" style and the Vosbikian Band was notable in the 40s and 50s for developing their own style of "kef music" heavily influenced by the popular American Big Band Jazz of the time. Later, stemming from the Middle Eastern Armenian diaspora and influenced by Continental European (especially French) pop music, the Armenian pop music genre grew to fame in the 60s and 70s with artists such as Adiss Harmandian and Harout Pamboukjian performing to the Armenian diaspora and Armenia. Also with artists such as Sirusho, performing pop music combined with Armenian folk music in today's entertainment industry. Other Armenian diasporans that rose to fame in classical or international music circles are world-renowned French-Armenian singer and composer Charles Aznavour, pianist Sahan Arzruni, prominent opera sopranos such as Hasmik Papian and more recently Isabel Bayrakdarian and Anna Kasyan. Certain Armenians settled to sing non-Armenian tunes such as the heavy metal band System of a Down (which nonetheless often incorporates traditional Armenian instrumentals and styling into their songs) or pop star Cher (whose father was Armenian). Ruben Hakobyan (Ruben Sasuntsi) is a well recognized Armenian ethnographic and patriotic folk singer who has achieved widespread national recognition due to his devotion to Armenian folk music and exceptional talent. In the Armenian diaspora, Armenian Revolutionary Songs are popular with the youth. These songs encourage Armenian patriotism and are generally about Armenian history and national heroes.

Carpet weaving

Carpet-weaving is historically a major traditional profession for the majority of Armenian women, including many Armenian families. Prominent Karabakh carpet weavers there were men too. The oldest extant Armenian carpet from the region, referred to as Artsakh (see also Karabakh carpet) during the medieval era, is from the village of Banants (near Gandzak) and dates to the early 13th century.[107] The first time that the Armenian word for carpet, kork, was used in historical sources was in a 1242–1243 Armenian inscription on the wall of the Kaptavan Church in Artsakh.[108]

Common themes and patterns found on Armenian carpets were the depiction of dragons and eagles. They were diverse in style, rich in color and ornamental motifs, and were even separated in categories depending on what sort of animals were depicted on them, such as artsvagorgs (eagle-carpets), vishapagorgs (dragon-carpets) and otsagorgs (serpent-carpets).[108] The rug mentioned in the Kaptavan inscriptions is composed of three arches, "covered with vegatative ornaments", and bears an artistic resemblance to the illuminated manuscripts produced in Artsakh.[108]

The art of carpet weaving was in addition intimately connected to the making of curtains as evidenced in a passage by Kirakos Gandzaketsi, a 13th-century Armenian historian from Artsakh, who praised Arzu-Khatun, the wife of regional prince Vakhtang Khachenatsi, and her daughters for their expertise and skill in weaving.[109]

Armenian carpets were also renowned by foreigners who traveled to Artsakh; the Arab geographer and historian Al-Masudi noted that, among other works of art, he had never seen such carpets elsewhere in his life.[110]

Cuisine

Khorovats, an Armenian-styled barbecue, is arguably the favorite Armenian dish. Lavash is a very popular Armenian flat bread, and Armenian paklava is a popular dessert made from filo dough. Other famous Armenian foods include the kabob (a skewer of marinated roasted meat and vegetables), various dolmas (minced lamb, or beef meat and rice wrapped in grape leaves, cabbage leaves, or stuffed into hollowed vegetables), and pilaf, a rice dish. Also, ghapama, a rice-stuffed pumpkin dish, and many different salads are popular in Armenian culture. Fruits play a large part in the Armenian diet. Apricots (Prunus armeniaca, also known as Armenian Plum) have been grown in Armenia for centuries and have a reputation for having an especially good flavor. Peaches are popular as well, as are grapes, figs, pomegranates, and melons. Preserves are made from many fruits, including cornelian cherries, young walnuts, sea buckthorn, mulberries, sour cherries, and many others.

Institutions

- The Armenian Apostolic Church, the world's oldest National Church

- The Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU) founded in 1906 and the largest Armenian non-profit organization in the world, with educational, cultural and humanitarian projects on all continents

- The Armenian Revolutionary Federation, founded in 1890. It is generally referred to as the Dashnaktsutyun, which means Federation in Armenian. The ARF is the strongest worldwide Armenian political organization and the only diasporan Armenian organization with a significant political presence in Armenia.

- Hamazkayin, an Armenian cultural and educational society founded in Cairo in 1928, and responsible for the founding of Armenian secondary schools and institutions of higher education in several countries

- The Armenian Catholic Church, representing small communities of Armeno-Catholics in different countries around the world, as well as important monastic and cultural institutions in Venice and Vienna

- Homenetmen, an Armenian Scouting and athletic organization founded in 1910 with a worldwide membership of about 25,000

- The Armenian Relief Society, founded in 1910

Genetics

Y-DNA

A 2012 study found that haplogroups R1b, J2, and T were the most notable haplogroups among Armenians.[111]

MtDNA

Most notable mtDNA haplogroups among the Armenian samples are H, U, T, J, K and X while the rest of remaining Mtdna of the Armenians are HV, I, X, W, R0 and N.[112]

See also

- Ethnic groups in Europe

- Ethnic groups in West Asia

- Hayk

- Hemshin peoples

- Hidden Armenians

- Peoples of the Caucasus

- Prehistory of the Armenians

- List of Armenian ethnic enclaves

- Armenian diaspora

References

Notes

- The political status of Abkhazia is disputed. Having unilaterally declared independence from Georgia in 1992, Abkhazia is formally recognised as an independent state by 5 UN member states (two other state recognised it but then withdrew its recognition), while Georgia continues to claim it as part of its own territory, designating it as Russian-occupied territory.

- The Republic of Artsakh is de facto independent and mainly integrated into Armenia, however, it is internationally recognized as de jure part of Azerbaijan.

- The number of Syrian Armenians is estimated to be far lower due to the Syrian Civil War, as these are pre-war figures. Many fled to Lebanon, Armenia, and the West respectively.

Inline

- Different sources:

- Dennis J.D. Sandole (24 January 2007). Peace and Security in the Postmodern World: The OSCE and Conflict Resolution. Routledge. p. 182. ISBN 9781134145713.

The nearly 3 million Armenians in Armenia (and 3–4 million in the Armenian Diaspora worldwide) 'perceive' the nearly 8 million Azerbaijanis in Azerbaijan as 'Turks.'

- McGoldrick, Monica; Giordano, Joe; Garcia-Preto, Nydia, eds. (18 August 2005). Ethnicity and Family Therapy, Third Edition (3 ed.). Guilford Press. p. 439. ISBN 9781606237946.

The impact of such a horror on a group who presently number approximately 6 million, worldwide, is incalculable.

- Sargsyan, Gevorg; Balabanyan, Ani; Hankinson, Denzel (2006). From Crisis to Stability in the Armenian Power Sector: Lessons Learned from Armenia's Energy Reform Experience (illustrated ed.). World Bank Publications. p. 18. ISBN 9780821365908.

The country's estimated 3–6 million diaspora represent a major source of foreign direct investment in the country.

- Arthur G. Sharp (15 September 2011). The Everything Guide to the Middle East: Understand the people, the politics, and the culture of this conflicted region. Adams Media. p. 137. ISBN 9781440529122.

Since the newly independent Republic of Armenia was declared in 1991, nearly 4 million of the world's 6 million Armenians have been living on the eastern edge of their Middle Eastern homeland.

- Dennis J.D. Sandole (24 January 2007). Peace and Security in the Postmodern World: The OSCE and Conflict Resolution. Routledge. p. 182. ISBN 9781134145713.

- different sources:

- Von Voss, Huberta (2007). Portraits of Hope: Armenians in the Contemporary World. New York: Berghahn Books. p. xxv. ISBN 9781845452575.

...there are some 8 million Armenians in the world...

- Freedman, Jeri (2008). The Armenian genocide. New York: Rosen Publishing Group. p. 52. ISBN 9781404218253.

In contrast to its population of 3.2 million, approximately 8 million Armenians live in other countries of the world, including large communities in the America and Russia.

- Guntram H. Herb, David H. Kaplan (2008). Nations and Nationalism: A Global Historical Overview: A Global Historical Overview. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 1705. ISBN 9781851099085.

A nation of some 8 million people, about 3 million of whom live in the newly independent post-Soviet state, Armenians are constantly battling not to lose their distinct culture, identity and the newly established statehood.

- Robert A. Saunders; Vlad Strukov (2010). Historical dictionary of the Russian Federation. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. p. 50. ISBN 9780810854758.

- Philander, S. George (2008). Encyclopedia of global warming and climate change. Los Angeles: SAGE. p. 77. ISBN 9781412958783.

An estimated 60 percent of the total 8 million Armenians worldwide live outside the country...

- Robert A. Saunders; Vlad Strukov (2010). Historical dictionary of the Russian Federation. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. p. 51. ISBN 9780810874602.

Worldwide, there are more than 8 million Armenians; 3.2 million reside in the Republic of Armenia.

- Von Voss, Huberta (2007). Portraits of Hope: Armenians in the Contemporary World. New York: Berghahn Books. p. xxv. ISBN 9781845452575.

- Archived 21 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine հոկտեմբերի 12-21-ը Հայաստանի Հանրապետությունում անցկացված մարդահամարի արդյունքները (The results of the census conducted in October 2011 in the Republic of Armenia). pp. 6–7. (in Armenian)

- Ministry of Culture of Armenia "The ethnic minorities in Armenia. Brief information" Archived 10 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine. As per the most recent census in 2011. "National minority" Archived 16 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Национальный состав населения Российской Федерации" [National makeup of the population of the Russian Federation] (Excel) (in Russian). Russian Federal State Statistics Service. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- Robert A. Saunders; Vlad Strukov (2010). Historical dictionary of the Russian Federation. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-8108-5475-8.

- Total ancestry categories tallied for people with one or more ancestry categories reported 2011 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

-

- Milliken, Mary (12 October 2007). "Armenian-American clout buys genocide breakthrough". Reuters. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- "Barack Obama on the Importance of US-Armenia Relations". Armenian National Committee of America. 19 January 2008. Archived from the original on 6 January 2013. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- Thon, Caroline (2012). Armenians in Hamburg: an ethnographic exploration into the relationship between diaspora and success. Berlin: LIT Verlag Münster. p. 25. ISBN 978-3-643-90226-9.

- Taylor, Tony (2008). Denial: history betrayed. Carlton, Victoria: Melbourne University Pub. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-522-85482-4.

- "National Statistics Office of Georgia" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- В Абхазии объявили данные переписи населения. Delfi (in Russian). 29 December 2011. Archived from the original on 28 July 2019. Retrieved 20 August 2013. (According to the 2011 census).

- Republic of Artsakh. "Population estimates of NKR as of 01.01.2013". Archived from the original on 21 May 2020. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- Gibney, Matthew J. (2005). Immigration and asylum: from 1900 to the present. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-57607-796-2.

- Vardanyan, Tamara (21 June 2007). Իրանահայ համայնք. ճամպրուկային տրամադրություններ [The Iranian-Armenian community] (in Armenian). Noravank Foundation. Archived from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- Sargsyan, Babken (8 December 2012). "Գերմանիաիի հայ համայնքը [Armenian community of Germany]" (in Armenian). Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- "The Virtual Museum of Armenian Diaspora". Ministry of Diaspora of the Republic of Armenia. Archived from the original on 19 February 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- The distribution of the population by nationality and mother tongue, Kiev: State Statistics Committee of Ukraine, 2001, retrieved 5 January 2013

- Comunidade armênia prospera no Brasil, mas não abandona luta pela memória do massacre Archived 10 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. By Breno Salvador. O Globo, 24 April 2015

- "Federal Senate of Brazil Recognizes Armenian Genocide". Armenian Weekly. 3 June 2015. Archived from the original on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- Bedevyan, Astghik (18 January 2011). "Հունաստանի հայ համայնքը պատրաստվում է Հայաստանի նախագահի հետ հանդիպմանը [Armenian community of Greece preparing for the meeting with the Armenian president]" (in Armenian). Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty Armenian Service. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- Ayvazyan 2003, p. 100.

- "Foreign Ministry: 89,000 minorities live in Turkey". Today's Zaman. 15 December 2008. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- Canada National Household Survey, Statistics Canada, 2011, archived from the original on 24 December 2018, retrieved 20 August 2013. Of those, 31,075 reported single and 24,675 mixed Armenian ancestry.

- Harutyunyan, Gagik (2009). ՀԱՅԿԱԿԱՆ ՏԵՂԵԿԱՏՎԱԿԱՆ ՀԱՄԱՅՆՔԱՅԻՆ ՌԵՍՈՒՐՍՆԵՐԸ ՀԵՏԽՈՐՀՐԴԱՅԻՆ ԵՐԿՐՆԵՐՈՒՄ (PDF). p. 117. ISBN 9789939900070.

- "Narodowy Spis Powszechny 2011 (Polish Census of 2011)". Główny Urząd Statystyczny (Polish Central Statistical Office). 2011. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- "Բելգիայում հայերի ներկայությունն անփոխարինելի է. Բրյուսելի քաղաքապետ". 1lurer. 22 February 2020. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- "Armenian Diaspora in Spain". Embassy of the Republic of Armenia to Spain. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Armenia. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- "Численность населения Республики Казахстан по отдельным этносам на начало 2020 года". Комитет по статистике Министерства национальной экономики Республики Казахстан. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "Ancestry | Australia | Community profile". profile.id.com.au. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- "Diaspora – United Arab Emirates".

- "CBS Statline".

- "Bevolking; geslacht, leeftijd, generatie en migratieachtergrond, 1 januari" (in Dutch). Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS). 22 July 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2022.

- "Armenia: Ancient and premodern Armenia". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Archived from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

The Armenians, an Indo-European people, first appear in history shortly after the end of the 7th century BCE[, d]riving some of the ancient population to the east of Mount Ararat [...]

- Richard G. Hovannisian, The Armenian people from ancient to modern times: the fifteenth century to the twentieth century, Volume 2, p. 421, Palgrave Macmillan, 1997.

- "Armenian (people) | Description, Culture, History, & Facts". Archived from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- see Hastings, Adrian (2000). A World History of Christianity. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 289. ISBN 978-0-8028-4875-8.

- "Armenia first nation to adopt Christianity as a state religion". Archived from the original on 6 January 2011. Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- "Χαλύβοισι πρὸς νότον Ἀρμένιοι ὁμουρέουσι (The Armenians border on the Chalybes to the south)". Chahin, Mark (2001). The Kingdom of Armenia. London: Routledge. pp. fr. 203. ISBN 978-0-7007-1452-0.

- Ibp Inc. (September 2013). Armenia Country Study Guide Volume 1 Strategic Information and Developments. p. 42. ISBN 9781438773827.

- Armen Petrosyan. The Indo-European and Ancient Near Eastern Sources of the Armenian Epic. Journal of Indo-European Studies. Institute for the Study of Man. 2002. p. 184.

- Armen Petrosyan. The Indo-European and Ancient Near Eastern Sources of the Armenian Epic. Journal of Indo-European Studies. Institute for the Study of Man. 2002. pp. 166–167.

- Archi, Alfonso (2016). "Egypt or Iran in the Ebla Texts?". Orientalia. 85: 3. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- Kroonen, Guus; Gojko Barjamovic; Michaël Peyrot (9 May 2018). "Linguistic supplement to Damgaard et al. 2018: Early Indo-European languages, Anatolian, Tocharian and Indo-Iranian": 3. doi:10.5281/zenodo.1240524. Archived from the original on 29 June 2019. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Razmik Panossian, The Armenians: From Kings And Priests to Merchants And Commissars, Columbia University Press (2006), ISBN 978-0-231-13926-7, p. 106.

- Rafael Ishkhanyan, "Illustrated History of Armenia," Yerevan, 1989

- Elisabeth Bauer. Armenia: Past and Present (1981), p. 49

- Petrosyan, Armen (2007). "Towards the Origins of the Armenian People: The Problem of Identification of the Proto-Armenians: A Critical Review (in English)". Journal for the Society of Armenian Studies. 16: 30. Archived from the original on 4 October 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- Martirosyan, Hrach (2010). Etymological Dictionary of the Armenian Inherited Lexicon. Leiden: Brill. pp. 382–385.

- Hamp, Eric P. (August 2013). "The Expansion of the Indo-European Languages: An Indo-Europeanist's Evolving View" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers. 239: 8, 10, 13. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 August 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- James P.T. Clackson (2008). "Classical Armenian."The Ancient Languages of Asia Minor. Cambridge University Press. p. 124

- Bartomeu Obrador-Cursach. "On the place of Phrygian among the Indo-European languages." Journal of Language Relationship. 2019. p. 240. https://www.jolr.ru/files/(271)jlr2019-17-3-4(233-245).pdf Archived 24 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Armen Petrosyan (2007). The Problem Of Identification Of The Proto-Armenians: A Critical Review. Society For Armenian Studies. pp. 49–54. Archived from the original on 4 October 2020. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- Martirosyan, Hrach (2014). "Origins and Historical Development of the Armenian Language" (PDF). Leiden University. pp. 1–23. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 August 2019. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- "The Mushki Problem Reconsidered". Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- Handbook of Formal Languages (1997) p. 6 Archived 18 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Indo-European tree with Armeno-Aryan, exclusion of Greek". Archived from the original on 14 May 2018. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction, Benjamin W. Fortson, John Wiley and Sons, 2009, p383.

- Hans J. Holm (2011): “Swadesh lists” of Albanian Revisited and Consequences for its position in the Indo-European Languages. The Journal of Indo-European Studies, Volume 39, Number 1&2.

- Hrach Martirosyan (2013). "The place of Armenian in the Indo-European language family: the relationship with Greek and Indo-Iranian*" Leiden University. p. 85-86. https://www.jolr.ru/files/(128)jlr2013-10(85-138).pdf Archived 24 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- James P.T. Clackson (2008). "Classical Armenian." The Ancient Languages of Asia Minor. Cambridge University Press. p. 124

- Hrach Martirosyan. The place of Armenian in the Indo-European language family: the relationship with Greek and Indo-Iranian. Journal of Language Relationship • Вопросы языкового родства • 10 (2013) • Pp. 85—137

- Handbook of Formal Languages (1997), p. 6 Archived 18 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine.

- Kim, Ronald (2018). "Greco-Armenian: The persistence of a myth". Indogermanische Forschungen. The University of British Columbia Library. doi:10.1515/if-2018-0009. S2CID 231923312. Archived from the original on 24 March 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- Greppin, John A. C.; Diakonoff, I. M. (1991). "Some Effects of the Hurro-Urartian People and Their Languages upon the Earliest Armenians". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 111 (4): 720–730. doi:10.2307/603403. JSTOR 603403.

- Joan Aruz, Kim Benzel, Jean M. Evans, Beyond Babylon: Art, Trade, and Diplomacy in the Second Millennium B.C. Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.) (2008) pp. 92

- Kossian, Aram V. (1997), The Mushki Problem Reconsidered, archived from the original on 29 August 2019, retrieved 31 August 2019 pp. 254

- Peter I. Bogucki and Pam J. Crabtree Ancient Europe, 8000 B.C. to A.D. 1000: An Encyclopedia of the Barbarian World. Archived 9 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine Charles Scribner's Sons, 2004 ISBN 978-0684806686

- Daniel T. Potts A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. Archived 19 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine Volume 94 of Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World. John Wiley & Sons, 2012 ISBN 1405189886 p.681

- Simonyan, Hakob Y. (2012). "New Discoveries at Verin Naver, Armenia". Backdirt. The Cotsen Institute of Archaeology at UCLA (The Puzzle of the Mayan Calendar): 110–113. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- Thomas Gamkrelidze and Vyacheslav Ivanov (philologist)|Vyacheslav V. Ivanov, The Early History of Indo-European Languages, March 1990, p. 110.

- Reich, David (2018). Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

- Damgaard, Peter de Barros (2018). The First Horse herders and the Impact of Early Bronze Age Steppe expansions into Asia.

- Haak, Wolfgang (2015). Massive migration from the steppe is a source for Indo-European languages in Europe. bioRxiv 10.1101/013433. doi:10.1101/013433. S2CID 196643946.

- Grolle, Johann (12 May 2018), "Invasion aus der Steppe", Der Spiegel

- Shaw, Jonathan (25 August 2022). "Seeking the First Speakers of Indo-European Language". Harvard Magazine. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- Haber, Marc; Mezzavilla, Massimo; Xue, Yali; Comas, David; Gasparini, Paolo; Zalloua, Pierre; Tyler-Smith, Chris (2015). "Genetic evidence for an origin of the Armenians from Bronze Age mixing of multiple populations". European Journal of Human Genetics. 24 (6): 931–936. bioRxiv 10.1101/015396. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2015.206. PMC 4820045. PMID 26486470.

- Wade, Nicholas (10 March 2015). "Date of Armenia's Birth, Given in 5th Century, Gains Credence". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- Wang, Chuan-Chao (2018), The genetic prehistory of the Greater Caucasus

- Vahan Kurkjian, "History of Armenia", Michigan, 1968, History of Armenia by Vahan Kurkjian Archived 27 May 2012 at archive.today; Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia, v. 12, Yerevan 1987; Artak Movsisyan, "Sacred Highland: Armenia in the spiritual conception of the Near East", Yerevan, 2000; Martiros Kavoukjian, "The Genesis of Armenian People", Montreal, 1982

- Curtis, John (November 2003). "The Achaemenid Period in Northern Iraq". L'archéologie de l'empire achéménide (Paris, France): 12.

- Hawkins, J. D. (1972). "Building Inscriptions of Carchemish: The Long Wall of Sculpture and Great Staircase". Anatolian Studies. 22: 87–114. doi:10.2307/3642555. JSTOR 3642555. S2CID 191397893.

- Redgate, A. E. (2007). "Reviewed work: The Pre-History of the Armenians, Gabriel Soultanian". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 70 (1): 173–175. doi:10.1017/S0041977X07000195. JSTOR 40378911. S2CID 163000249.

- Mary Boyce. Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices Archived 21 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine Psychology Press, 2001 ISBN 978-0415239028 p 84

- "The conversion of Armenia to Christianity was probably the most crucial step in its history. It turned Armenia sharply away from its Iranian past and stamped it for centuries with an intrinsic character as clear to the native population as to those outside its borders, who identified Armenia almost at once as the first state to adopt Christianity". (Nina Garsoïan in Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times, ed. R.G. Hovannisian, Palgrave Macmillan, 1997, Volume 1, p.81).

- traditionally dated to 301 following Mikayel Chamchian (1784). 314 is the date favored by mainstream scholarship, so Nicholas Adontz (1970), p.82, following the research of Ananian, and Seibt The Christianization of Caucasus (Armenia, Georgia, Albania) (2002).

- Mary Boyce. Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices Archived 19 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine Psychology Press, 2001 ISBN 0415239028 p 84

- Charl Wolhuter, Corene de Wet. International Comparative Perspectives on Religion and Education Archived 18 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine AFRICAN SUN MeDIA, ISBN 1920382372. 1 March 2014 p 31

- Hodgson, Natasha (2010). Kostick, Conor (ed.). The Crusades and the Near East: Cultural Histories. Routledge. ISBN 978-1136902475. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- Donald Rayfield. Edge of Empires: A History of Georgia Archived 18 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine Reaktion Books, 2013 ISBN 1780230702 p 165

- Steven R. Ward. Immortal, Updated Edition: A Military History of Iran and Its Armed Forces Archived 18 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine Georgetown University Press, 8 January 2014 ISBN 1626160325 p 43

- Herzig, Edmund; Kurkchiyan, Marina (10 November 2004). Armenians: Past and Present in the Making of National Identity. ISBN 9781135798376. Archived from the original on 24 March 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- Timothy C. Dowling Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond Archived 3 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine pp 728 ABC-CLIO, 2 December 2014 ISBN 1598849484

- Vahan Kurkjian, "History of Armenia", Michigan, 1968, History of Armenia by Vahan Kurkjian Archived 27 May 2012 at archive.today

- "Armenian Quarter in Jerusalem". Archived from the original on 7 March 2007. Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- Khojoyan, Sara (16 October 2009). "Armenian in Istanbul: Diaspora in Turkey welcomes the setting of relations and waits more steps from both countries". ArmeniaNow.com. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- The Cambridge Ancient History. vol. 12, p. 486. London: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Terzian, Shelley (2014). Wolhuter, Charl; de Wet, Corene (eds.). International Comparative Perspectives on Religion and Education. African Sun Media. p. 29. ISBN 978-1920382377. Archived from the original on 15 June 2016. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- "Agathangelos, History of St. Gregory and the Conversion of Armenia". Archived from the original on 30 September 2018. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- Agathangelos, History of the Armenians, Robert W. Thomson, State University of New York Press, 1974

- "A Migrating Catholicosate". Archived from the original on 3 April 2008. Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- Hamed-Troyansky, Vladimir (2021). "Becoming Armenian: Religious Conversions in the Late Imperial South Caucasus". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 63 (1): 242–272. doi:10.1017/S0010417520000432.

- "Two Catholicosates within the Armenian Church". Archived from the original on 24 May 2008. Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- "Sacred Geometry and Armenian Architecture | Armenia Travel, History, Archeology & Ecology | TourArmenia | Travel Guide to Armenia". Archived from the original on 24 July 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2009.

- Armenia, Past and Present; Elisabeth Bauer, Jacob Schmidheiny, Frederick Leist, 1981

- "Sport in Armenia". Archived from the original on 19 November 2015. Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- Hakobyan, Hravard H. (1990). The Medieval Art of Artsakh. Yerevan, Armenian SSR: Parberakan. p. 84. ISBN 978-5-8079-0195-8.

- Hakobyan. Medieval Art of Artsakh, p. 84.

- (in Armenian) Kirakos Gandzaketsi. Պատմություն Հայոց (History of Armenia). Yerevan, Armenian SSR: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1961, p. 216, as cited in Hakobyan. Medieval Art of Artsakh, p. 84, note 18.

- Ulubabyan, Bagrat A. (1975). Խաչենի իշխանությունը, X-XVI դարերում (The Principality of Khachen, From the 10th to 16th Centuries) (in Armenian). Yerevan, Armenian SSR: Armenian Academy of Sciences. p. 267.

- Herrera KJ, Lowery RK, Hadden L, Calderon S, Chiou C, Yepiskoposyan L, Regueiro M, Underhill PA, Herrera RJ (March 2012). "Neolithic patrilineal signals indicate that the Armenian plateau was repopulated by agriculturalists". European Journal of Human Genetics. 20 (3): 313–20. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2011.192. PMC 3286660. PMID 22085901.

- Margaryan A, Derenko M, Hovhannisyan H, Malyarchuk B, Heller R, Khachatryan Z, Avetisyan P, Badalyan R, Bobokhyan A, Melikyan V, Sargsyan G, Piliposyan A, Simonyan H, Mkrtchyan R, Denisova G, Yepiskoposyan L, Willerslev E, Allentoft M (10 July 2017). "Eight Millennia of Matrilineal Genetic Continuity in the South Caucasus". Current Biology. 27 (13): 2023–2028. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.05.087. PMID 28669760. S2CID 23400138. "Figure 2". Archived from the original on 24 March 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

General

This article incorporates public domain material from World Factbook. CIA.

This article incorporates public domain material from World Factbook. CIA. This article incorporates public domain material from U.S. Bilateral Relations Fact Sheets. United States Department of State.

This article incorporates public domain material from U.S. Bilateral Relations Fact Sheets. United States Department of State.- The categorization of Armenian churches in Los Angeles used information from Sacred Transformation: Armenian Churches in Los Angeles Archived 29 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine a project of the USC School of Policy, Planning, and Development.

- Some of the information about the history of the Armenians comes from the multi-volume History of the Armenian People, Yerevan, Armenia, 1971.

Further reading

- Petrosyan, Armen (2006). "Towards the Origins of the Armenian People. The Problem of Identification of the Proto-Armenians: A Critical Review". Journal of the Society for Armenian Studies. 16: 25–66. ISSN 0747-9301.

- I. M. Diakonoff, The Pre-History of the Armenian People (revised, trans. Lori Jennings), Caravan Books, New York (1984), ISBN 978-0-88206-039-2.

- George A. Bournoutian, A History of the Armenian People, 2 vol. (1994)

- Hovannisian, Richard G., ed. (September 1997), The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times, vol. I – The Dynastic Periods: From Antiquity to the Fourteenth Century, New York: St. Martin's Press, ISBN 978-0-312-10169-5

- Hovannisian, Richard G., ed. (September 1997), The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times , vol. II – Foreign Dominion to Statehood: The Fifteenth Century to the Twentieth Century, New York: St. Martin's Press, ISBN 0-312-10168-6

- Redgate, Anne Elizabeth (1999), The Armenians (1st ed.), Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers, ISBN 0-631-22037-2

- Aleksandra Ziolkowska-Boehm, The Polish Experience through World War II: A Better Day Has Not Come, Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2013, ISBN 978-0-7391-7819-5

- Russell D. Gray and Quentin D. Atkinson, "Language-tree divergence times support the Anatolian theory of Indo-European origin", Nature, 426, 435–439 (2003)

- George A. Bournoutian, A Concise History of the Armenian People (Mazda, 2003, 2004).

- Ayvazyan, Hovhannes (2003). Հայ Սփյուռք հանրագիտարան [Encyclopedia of Armenian Diaspora] (in Armenian). Vol. 1. Yerevan: Armenian Encyclopedia publishing. ISBN 978-5-89700-020-3.

- Stopka, Krzysztof (2016). Armenia Christiana: Armenian Religious Identity and the Churches of Constantinople and Rome (4th-15th century). Kraków: Jagiellonian University Press. ISBN 9788323395553.

- Marcarian, Mônica Nalbandian (2016). "Diáspora armênia no Brasil". Revista de Estudos Orientais (6): 109–115. doi:10.11606/issn.2763-650X.i6p109-115. - on Brazil's Armenian diaspora.

- UCLA conference series proceedings

The UCLA conference series titled "Historic Armenian Cities and Provinces" is organized by the Holder of the Armenian Educational Foundation Chair in Modern Armenian History. The conference proceedings are edited by Richard G. Hovannisian. Published in Costa Mesa, CA, by Mazda Publishers, they are:

- Armenian Van/Vaspurakan (2000) OCLC 44774992

- Armenian Baghesh/Bitlis and Taron/Mush (2001) OCLC 48223061

- Armenian Tsopk/Kharpert (2002) OCLC 50478560

- Armenian Karin/Erzerum (2003) OCLC 52540130

- Armenian Sebastia/Sivas and Lesser Armenia (2004) OCLC 56414051

- Armenian Tigranakert/Diarbekir and Edessa/Urfa (2006) OCLC 67361643

- Armenian Cilicia (2008) OCLC 185095701

- Armenian Pontus: the Trebizond-Black Sea communities (2009) OCLC 272307784