Art Deco

Art Deco, short for the French Arts Décoratifs, and sometimes just called Deco, is a style of visual arts, architecture, and product design, that first appeared in France in the 1910s (just before World War I),[1] and flourished in the United States and Europe during the 1920s and 1930s. Through styling and design of the exterior and interior of anything from large structures to small objects, including how people look (clothing, fashion and jewelry), Art Deco has influenced bridges, buildings (from skyscrapers to cinemas), ships, ocean liners, trains, cars, trucks, buses, furniture, and everyday objects like radios and vacuum cleaners.[2]

.jpg.webp)   Top to bottom: Chrysler Building in New York City (1930); poster for the Chicago World's Fair by Weimer Pursell (1933); and hood ornament Victoire by René Lalique (1928) | |

| Years active | c. 1910–1949 |

|---|---|

| Country | Global |

It got its name after the 1925 Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes (International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts) held in Paris.[3]

Art Deco combined modern styles with fine craftsmanship and rich materials. During its heyday, it represented luxury, glamour, exuberance, and faith in social and technological progress.

From its outset, Art Deco was influenced by the bold geometric forms of Cubism and the Vienna Secession; the bright colours of Fauvism and of the Ballets Russes; the updated craftsmanship of the furniture of the eras of Louis Philippe I and Louis XVI; and the exoticized styles of China, Japan, India, Persia, ancient Egypt and Maya art. It featured rare and expensive materials, such as ebony and ivory, and exquisite craftsmanship. The Empire State Building, Chrysler Building, and other skyscrapers of New York City built during the 1920s and 1930s are monuments to the style.

In the 1930s, during the Great Depression, Art Deco became more subdued. New materials arrived, including chrome plating, stainless steel and plastic. A sleeker form of the style, called Streamline Moderne, appeared in the 1930s, featuring curving forms and smooth, polished surfaces.[4] Art Deco is one of the first truly international styles, but its dominance ended with the beginning of World War II and the rise of the strictly functional and unadorned styles of modern architecture and the International Style of architecture that followed.[5]

Etymology

Art Deco took its name, short for arts décoratifs, from the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes held in Paris in 1925,[3] though the diverse styles that characterised it had already appeared in Paris and Brussels before World War I.

Arts décoratifs was first used in France in 1858 in the Bulletin de la Société française de photographie.[6] In 1868, the Le Figaro newspaper used the term objets d'art décoratifs for objects for stage scenery created for the Théâtre de l'Opéra.[7][8][9] In 1875, furniture designers, textile, jewellers, glass-workers, and other craftsmen were officially given the status of artists by the French government. In response, the École royale gratuite de dessin (Royal Free School of Design), founded in 1766 under King Louis XVI to train artists and artisans in crafts relating to the fine arts, was renamed the École nationale des arts décoratifs (National School of Decorative Arts). It took its present name, ENSAD (École nationale supérieure des arts décoratifs), in 1927.

At the 1925 Exposition, architect Le Corbusier wrote a series of articles about the exhibition for his magazine L'Esprit Nouveau, under the title "1925 EXPO. ARTS. DÉCO.", which were combined into a book, L'art décoratif d'aujourd'hui (Decorative Art Today). The book was a spirited attack on the excesses of the colourful, lavish objects at the Exposition, and on the idea that practical objects such as furniture should not have any decoration at all; his conclusion was that "Modern decoration has no decoration".[10]

The actual term art déco did not appear in print until 1966, in the title of the first modern exhibition on the subject, held by the Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris, Les Années 25 : Art déco, Bauhaus, Stijl, Esprit nouveau, which covered the variety of major styles in the 1920s and 1930s.[11] The term was then used in a 1966 newspaper article by Hillary Gelson in The Times (London, 12 November), describing the different styles at the exhibit.[12]

Art Deco gained currency as a broadly applied stylistic label in 1968 when historian Bevis Hillier published the first major academic book on it, Art Deco of the 20s and 30s.[2] He noted that the term was already being used by art dealers, and cites The Times (2 November 1966) and an essay named Les Arts Déco in Elle magazine (November 1967) as examples.[13] In 1971, he organized an exhibition at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, which he details in his book The World of Art Deco.[14][15]

Origins

Society of Decorative Artists (1901–1945)

The emergence of Art Deco was closely connected with the rise in status of decorative artists, who until late in the 19th century were considered simply as artisans. The term arts décoratifs had been invented in 1875, giving the designers of furniture, textiles, and other decoration official status. The Société des artistes décorateurs (Society of Decorative Artists), or SAD, was founded in 1901, and decorative artists were given the same rights of authorship as painters and sculptors. A similar movement developed in Italy. The first international exhibition devoted entirely to the decorative arts, the Esposizione Internazionale d'Arte Decorativa Moderna, was held in Turin in 1902. Several new magazines devoted to decorative arts were founded in Paris, including Arts et décoration and L'Art décoratif moderne. Decorative arts sections were introduced into the annual salons of the Sociéte des artistes français, and later in the Salon d'Automne. French nationalism also played a part in the resurgence of decorative arts, as French designers felt challenged by the increasing exports of less expensive German furnishings. In 1911, SAD proposed a major new international exposition of decorative arts in 1912. No copies of old styles would be permitted, only modern works. The exhibit was postponed until 1914; and then, because of the war, until 1925, when it gave its name to the whole family of styles known as "Déco".[16]

Table and chairs by Maurice Dufrêne and carpet by Paul Follot at the 1912 Salon des artistes décorateurs

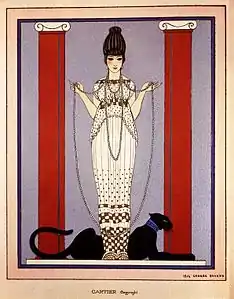

Table and chairs by Maurice Dufrêne and carpet by Paul Follot at the 1912 Salon des artistes décorateurs Lady with Panther by George Barbier for Louis Cartier, 1914. Display card commissioned by Cartier shows a woman in a Paul Poiret gown (1914)

Lady with Panther by George Barbier for Louis Cartier, 1914. Display card commissioned by Cartier shows a woman in a Paul Poiret gown (1914) Armchair by Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann (1914) (Musée d'Orsay)

Armchair by Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann (1914) (Musée d'Orsay)

Parisian department stores and fashion designers also played an important part in the rise of Art Deco. Prominent businesses such as silverware firm Christofle, glass designer René Lalique, and the jewellers Louis Cartier and Boucheron began designing products in more modern styles.[17][18] Beginning in 1900, department stores recruited decorative artists to work in their design studios. The decoration of the 1912 Salon d'Automne was entrusted to the department store Printemps,[19][20] and that year it created its own workshop, Primavera.[20] By 1920 Primavera employed more than 300 artists, whose styles ranged from updated versions of Louis XIV, Louis XVI, and especially Louis Philippe furniture made by Louis Süe and the Primavera workshop, to more modern forms from the workshop of the Au Louvre department store. Other designers, including Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann and Paul Follot, refused to use mass production, insisting that each piece be made individually. The early Art Deco style featured luxurious and exotic materials such as ebony, ivory and silk, very bright colours and stylized motifs, particularly baskets and bouquets of flowers of all colours, giving a modernist look.[21]

Vienna Secession and Wiener Werkstätte (1897–1912)

The architects of the Vienna Secession (formed 1897), especially Josef Hoffmann, had a notable influence on Art Deco. His Stoclet Palace, in Brussels (1905–1911), was a prototype of the Art Deco style, featuring geometric volumes, symmetry, straight lines, concrete covered with marble plaques, finely-sculpted ornament, and lavish interiors, including mosaic friezes by Gustav Klimt. Hoffmann was also a founder of the Wiener Werkstätte (1903–1932), an association of craftsmen and interior designers working in the new style. This became the model for the Compagnie des arts français, created in 1919, which brought together André Mare, and Louis Süe, the first leading French Art Deco designers and decorators.[22]

Secession Building by Joseph Maria Olbrich, Vienna (1897–98)

Secession Building by Joseph Maria Olbrich, Vienna (1897–98) Stoclet Palace by Josef Hoffmann, Brussels (1905–1911)

Stoclet Palace by Josef Hoffmann, Brussels (1905–1911).jpg.webp) Detail of the Stoclet Palace's façade, made of reinforced concrete covered with marble plaques

Detail of the Stoclet Palace's façade, made of reinforced concrete covered with marble plaques Austrian Postal Savings Bank by Otto Wagner, Vienna (1904–1912)

Austrian Postal Savings Bank by Otto Wagner, Vienna (1904–1912)

New materials and technologies

New materials and technologies, especially reinforced concrete, were key to the development and appearance of Art Deco. The first concrete house was built in 1853 in the Paris suburbs by François Coignet. In 1877 Joseph Monier introduced the idea of strengthening the concrete with a mesh of iron rods in a grill pattern. In 1893 Auguste Perret built the first concrete garage in Paris, then an apartment building, house, then, in 1913, the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. The theatre was denounced by one critic as the "Zeppelin of Avenue Montaigne", an alleged Germanic influence, copied from the Vienna Secession. Thereafter, the majority of Art Deco buildings were made of reinforced concrete, which gave greater freedom of form and less need for reinforcing pillars and columns. Perret was also a pioneer in covering the concrete with ceramic tiles, both for protection and decoration. The architect Le Corbusier first learned the uses of reinforced concrete working as a draftsman in Perret's studio.[23]

Other new technologies that were important to Art Deco were new methods in producing plate glass, which was less expensive and allowed much larger and stronger windows, and for mass-producing aluminium, which was used for building and window frames and later, by Corbusier, Warren McArthur, and others, for lightweight furniture.

Théâtre des Champs-Élysées (1910–1913)

Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, by Auguste Perret, 15 avenue Montaigne, Paris (1910–13). Reinforced concrete gave architects the ability to create new forms and bigger spaces

Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, by Auguste Perret, 15 avenue Montaigne, Paris (1910–13). Reinforced concrete gave architects the ability to create new forms and bigger spaces.jpg.webp) Antoine Bourdelle, La Danse, on the façade of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées (1912)

Antoine Bourdelle, La Danse, on the façade of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées (1912) Interior of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, with Bourdelle's bas-reliefs over the stage

Interior of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, with Bourdelle's bas-reliefs over the stage Dome of the Theater, with Art Deco rose design by Maurice Denis

Dome of the Theater, with Art Deco rose design by Maurice Denis

The Théâtre des Champs-Élysées (1910–1913), by Auguste Perret, was the first landmark Art Deco building completed in Paris. Previously, reinforced concrete had been used only for industrial and apartment buildings, Perret had built the first modern reinforced-concrete apartment building in Paris on rue Benjamin Franklin in 1903–04. Henri Sauvage, another important future Art Deco architect, built another in 1904 at 7, rue Trétaigne (1904). From 1908 to 1910, the 21-year-old Le Corbusier worked as a draftsman in Perret's office, learning the techniques of concrete construction. Perret's building had clean rectangular form, geometric decoration and straight lines, the future trademarks of Art Deco. The décor of the theatre was also revolutionary; the façade was decorated with high reliefs by Antoine Bourdelle, a dome by Maurice Denis, paintings by Édouard Vuillard, and an Art Deco curtain by Ker-Xavier Roussel. The theatre became famous as the venue for many of the first performances of the Ballets Russes.[24] Perret and Sauvage became the leading Art Deco architects in Paris in the 1920s.[25][26]

Salon d'Automne (1903–1914)

_02_by_L._Bakst_2.jpg.webp) Set for Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov's ballet Sheherazade by Léon Bakst (1910)

Set for Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov's ballet Sheherazade by Léon Bakst (1910) Art Deco armchair made for art collector Jacques Doucet (1912–13)

Art Deco armchair made for art collector Jacques Doucet (1912–13).jpg.webp) Display of early Art Deco furnishings by the Atelier français at the 1913 Salon d'Automne from Art et décoration magazine (1914)

Display of early Art Deco furnishings by the Atelier français at the 1913 Salon d'Automne from Art et décoration magazine (1914)

At its birth between 1910 and 1914, Art Deco was an explosion of colours, featuring bright and often clashing hues, frequently in floral designs, presented in furniture upholstery, carpets, screens, wallpaper and fabrics. Many colourful works, including chairs and a table by Maurice Dufrêne and a bright Gobelin carpet by Paul Follot were presented at the 1912 Salon des artistes décorateurs. In 1912–1913 designer Adrien Karbowsky made a floral chair with a parrot design for the hunting lodge of art collector Jacques Doucet.[27] The furniture designers Louis Süe and André Mare made their first appearance at the 1912 exhibit, under the name of the Atelier français, combining polychromatic fabrics with exotic and expensive materials, including ebony and ivory. After World War I, they became one of the most prominent French interior design firms, producing the furniture for the first-class salons and cabins of the French transatlantic ocean liners.[28]

The vivid hues of Art Deco came from many sources, including the exotic set designs by Léon Bakst for the Ballets Russes, which caused a sensation in Paris just before World War I. Some of the colours were inspired by the earlier Fauvism movement led by Henri Matisse; others by the Orphism of painters such as Sonia Delaunay;[29] others by the movement known as Les Nabis, and in the work of symbolist painter Odilon Redon, who designed fireplace screens and other decorative objects. Bright shades were a feature of the work of fashion designer Paul Poiret, whose work influenced both Art Deco fashion and interior design.[28][30][31]

Cubism

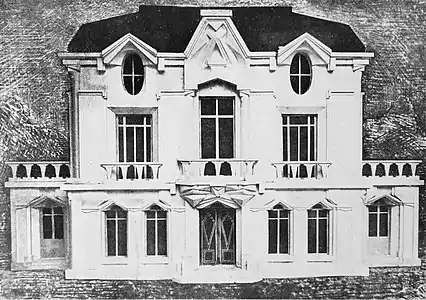

Design for the facade of La Maison Cubiste (Cubist House) by Raymond Duchamp-Villon (1912)

Design for the facade of La Maison Cubiste (Cubist House) by Raymond Duchamp-Villon (1912)_at_the_Salon_d'Automne%252C_1912%252C_detail_of_the_entrance._Photograph_by_Duchamp-Villon.jpg.webp) Raymond Duchamp-Villon, 1912, La Maison Cubiste (Cubist House) at the Salon d'Automne, 1912, detail of the entrance

Raymond Duchamp-Villon, 1912, La Maison Cubiste (Cubist House) at the Salon d'Automne, 1912, detail of the entrance Le Salon Bourgeois, designed by André Mare inside La Maison Cubiste, in the decorative arts section of the Salon d'Automne, 1912, Paris. Metzinger's Femme à l'Éventail on the left wall

Le Salon Bourgeois, designed by André Mare inside La Maison Cubiste, in the decorative arts section of the Salon d'Automne, 1912, Paris. Metzinger's Femme à l'Éventail on the left wall Stairway in the hôtel particulier of fashion designer-art collector Jacques Doucet (1927). Design by Joseph Csaky. The geometric forms of Cubism had an important influence on Art Deco

Stairway in the hôtel particulier of fashion designer-art collector Jacques Doucet (1927). Design by Joseph Csaky. The geometric forms of Cubism had an important influence on Art Deco Jacques Doucet's hôtel particulier, 1927. Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon can be seen hanging in the background

Jacques Doucet's hôtel particulier, 1927. Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon can be seen hanging in the background

The art movement known as Cubism appeared in France between 1907 and 1912, influencing the development of Art Deco.[24][29][30] In Art Deco Complete: The Definitive Guide to the Decorative Arts of the 1920s and 1930s Alastair Duncan writes "Cubism, in some bastardized form or other, became the lingua franca of the era's decorative artists."[30][32] The Cubists, themselves under the influence of Paul Cézanne, were interested in the simplification of forms to their geometric essentials: the cylinder, the sphere, the cone.[33][34]

In 1912, the artists of the Section d'Or exhibited works considerably more accessible to the general public than the analytical Cubism of Picasso and Braque. The Cubist vocabulary was poised to attract fashion, furniture and interior designers.[29][31][34][35]

The 1912 writings of André Vera, Le Nouveau style, published in the journal L'Art décoratif, expressed the rejection of Art Nouveau forms (asymmetric, polychrome and picturesque) and called for simplicité volontaire, symétrie manifeste, l'ordre et l'harmonie, themes that would eventually become common within Art Deco;[18] though the Deco style was often extremely colourful and often complex.[36]

In the Art Décoratif section of the 1912 Salon d'Automne, an architectural installation was exhibited known as La Maison Cubiste.[37][38] The facade was designed by Raymond Duchamp-Villon. The décor of the house was by André Mare.[39][40] La Maison Cubiste was a furnished installation with a façade, a staircase, wrought iron banisters, a bedroom, a living room—the Salon Bourgeois, where paintings by Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger, Marie Laurencin, Marcel Duchamp, Fernand Léger and Roger de La Fresnaye were hung.[41][42][43] Thousands of spectators at the salon passed through the full-scale model.[44]

The façade of the house, designed by Duchamp-Villon, was not very radical by modern standards; the lintels and pediments had prismatic shapes, but otherwise the façade resembled an ordinary house of the period. For the two rooms, Mare designed the wallpaper, which featured stylized roses and floral patterns, along with upholstery, furniture and carpets, all with flamboyant and colourful motifs. It was a distinct break from traditional décor. The critic Emile Sedeyn described Mare's work in the magazine Art et Décoration: "He does not embarrass himself with simplicity, for he multiplies flowers wherever they can be put. The effect he seeks is obviously one of picturesqueness and gaiety. He achieves it."[45] The Cubist element was provided by the paintings. The installation was attacked by some critics as extremely radical, which helped make for its success.[46] This architectural installation was subsequently exhibited at the 1913 Armory Show, New York City, Chicago and Boston.[29][34][47][48][49] Thanks largely to the exhibition, the term "Cubist" began to be applied to anything modern, from women's haircuts to clothing to theater performances."[46]

The Cubist influence continued within Art Deco, even as Deco branched out in many other directions.[29][30] In 1927, Cubists Joseph Csaky, Jacques Lipchitz, Louis Marcoussis, Henri Laurens, the sculptor Gustave Miklos, and others collaborated in the decoration of a Studio House, rue Saint-James, Neuilly-sur-Seine, designed by the architect Paul Ruaud and owned by the French fashion designer Jacques Doucet, also a collector of Post-Impressionist art by Henri Matisse and Cubist paintings (including Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, which he bought directly from Picasso's studio). Laurens designed the fountain, Csaky designed Doucet's staircase,[50] Lipchitz made the fireplace mantel, and Marcoussis made a Cubist rug.[29][51][52][53]

Besides the Cubist artists, Doucet brought in other Deco interior designers to help in decorating the house, including Pierre Legrain, who was in charge of organizing the decoration, and Paul Iribe, Marcel Coard, André Groult, Eileen Gray and Rose Adler to provide furniture. The décor included massive pieces made of macassar ebony, inspired by African art, and furniture covered with Morocco leather, crocodile skin and snakeskin, and patterns taken from African designs.[54]

Cubism's adumbrated geometry became coin of the realm in the 1920s. Art Deco's development of Cubism's selective geometry into a wider array of shapes carried Cubism as a pictorial taxonomy to a much broader audience and wider appeal. (Richard Harrison Martin, Metropolitan Museum of Art)[55]

Influences

%252C_Vaslav_Nijinsky_(1890-1950)%252C_1913_1.jpg.webp) The exoticism of the Ballets Russes had a strong influence on early Deco. A drawing of the dancer Vaslav Nijinsky by Paris fashion artist Georges Barbier (1913)

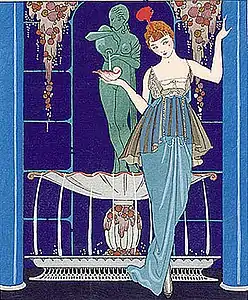

The exoticism of the Ballets Russes had a strong influence on early Deco. A drawing of the dancer Vaslav Nijinsky by Paris fashion artist Georges Barbier (1913) Illustration by Georges Barbier of a gown by Paquin (1914). Stylised floral designs and bright colours were a feature of early Art Deco.

Illustration by Georges Barbier of a gown by Paquin (1914). Stylised floral designs and bright colours were a feature of early Art Deco. Lobby of 450 Sutter Street, San Francisco, California, by Timothy Pflueger (1929), inspired by ancient Maya art

Lobby of 450 Sutter Street, San Francisco, California, by Timothy Pflueger (1929), inspired by ancient Maya art The gilded bronze Prometheus at Rockefeller Center, New York City, N.Y., by Paul Manship (1934), a stylised Art Deco update of classical sculpture (1936)

The gilded bronze Prometheus at Rockefeller Center, New York City, N.Y., by Paul Manship (1934), a stylised Art Deco update of classical sculpture (1936) A ceramic vase inspired by motifs of traditional African carved wood sculpture, by Emile Lenoble (1937), Museum of Decorative Arts, Paris

A ceramic vase inspired by motifs of traditional African carved wood sculpture, by Emile Lenoble (1937), Museum of Decorative Arts, Paris

Art Deco was not a single style, but a collection of different and sometimes contradictory styles. In architecture, Art Deco was the successor to and reaction against Art Nouveau, a style which flourished in Europe between 1895 and 1900, and also gradually replaced the Beaux-Arts and neoclassical that were predominant in European and American architecture. In 1905 Eugène Grasset wrote and published Méthode de Composition Ornementale, Éléments Rectilignes,[56] in which he systematically explored the decorative (ornamental) aspects of geometric elements, forms, motifs and their variations, in contrast with (and as a departure from) the undulating Art Nouveau style of Hector Guimard, so popular in Paris a few years earlier. Grasset stressed the principle that various simple geometric shapes like triangles and squares are the basis of all compositional arrangements. The reinforced-concrete buildings of Auguste Perret and Henri Sauvage, and particularly the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, offered a new form of construction and decoration which was copied worldwide.[57]

In decoration, many different styles were borrowed and used by Art Deco. They included pre-modern art from around the world and observable at the Musée du Louvre, Musée de l'Homme and the Musée national des Arts d'Afrique et d'Océanie. There was also popular interest in archaeology due to excavations at Pompeii, Troy, and the tomb of the 18th dynasty Pharaoh Tutankhamun. Artists and designers integrated motifs from ancient Egypt, Africa, Mesopotamia, Greece, Rome, Asia, Mesoamerica and Oceania with Machine Age elements.[58][59][60][61][62][63]

Other styles borrowed included Russian Constructivism and Italian Futurism, as well as Orphism, Functionalism, and Modernism in general.[34][58][64][65] Art Deco also used the clashing colours and designs of Fauvism, notably in the work of Henri Matisse and André Derain, inspired the designs of art deco textiles, wallpaper, and painted ceramics.[34] It took ideas from the high fashion vocabulary of the period, which featured geometric designs, chevrons, zigzags, and stylized bouquets of flowers. It was influenced by discoveries in Egyptology, and growing interest in the Orient and in African art. From 1925 onwards, it was often inspired by a passion for new machines, such as airships, automobiles and ocean liners, and by 1930 this influence resulted in the style called Streamline Moderne.[66]

Style of luxury and modernity

The boudoir of fashion designer Jeanne Lanvin (1922–25) now in the Museum of Decorative Arts, Paris, France

The boudoir of fashion designer Jeanne Lanvin (1922–25) now in the Museum of Decorative Arts, Paris, France Bath of Jeanne Lanvin, of Sienna marble, with decoration of carved stucco and bronze (1922–25)

Bath of Jeanne Lanvin, of Sienna marble, with decoration of carved stucco and bronze (1922–25) An Art Deco study by the Paris design firm of Alavoine, now in the Brooklyn Museum, New York City, N.Y. (1928–30)

An Art Deco study by the Paris design firm of Alavoine, now in the Brooklyn Museum, New York City, N.Y. (1928–30)%252C_Paris%252C_1922.jpg.webp) Glass Salon (Le salon de verre) designed by Paul Ruaud with furniture by Eileen Gray, for Madame Mathieu-Levy (milliner of the boutique J. Suzanne Talbot), 9, rue de Lota, Paris, 1922 (published in L'Illustration, 27 May 1933)

Glass Salon (Le salon de verre) designed by Paul Ruaud with furniture by Eileen Gray, for Madame Mathieu-Levy (milliner of the boutique J. Suzanne Talbot), 9, rue de Lota, Paris, 1922 (published in L'Illustration, 27 May 1933)

Art Deco was associated with both luxury and modernity; it combined very expensive materials and exquisite craftsmanship put into modernistic forms. Nothing was cheap about Art Deco: pieces of furniture included ivory and silver inlays, and pieces of Art Deco jewellery combined diamonds with platinum, jade, coral and other precious materials. The style was used to decorate the first-class salons of ocean liners, deluxe trains, and skyscrapers. It was used around the world to decorate the great movie palaces of the late 1920s and 1930s. Later, after the Great Depression, the style changed and became more sober.

A good example of the luxury style of Art Deco is the boudoir of the fashion designer Jeanne Lanvin, designed by Armand-Albert Rateau (1882–1938) made between 1922 and 1925. It was located in her house at 16 rue Barbet de Jouy, in Paris, which was demolished in 1965. The room was reconstructed in the Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris. The walls are covered with moulded lambris below sculpted bas-reliefs in stucco. The alcove is framed with columns of marble on bases and a plinth of sculpted wood. The floor is of white and black marble, and in the cabinets decorative objects are displayed against a background of blue silk. Her bathroom had a tub and washstand made of sienna marble, with a wall of carved stucco and bronze fittings.[67]

By 1928 the style had become more comfortable, with deep leather club chairs. The study designed by the Paris firm of Alavoine for an American businessman in 1928–30, is now in the Brooklyn Museum.

By the 1930s, the style had been somewhat simplified, but it was still extravagant. In 1932 the decorator Paul Ruaud made the Glass Salon for Suzanne Talbot. It featured a serpentine armchair and two tubular armchairs by Eileen Gray, a floor of mat silvered glass slabs, a panel of abstract patterns in silver and black lacquer, and an assortment of animal skins.[68]

International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts (1925)

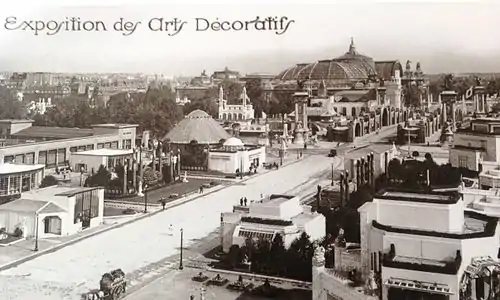

Postcard of the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris, France (1925)

Postcard of the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris, France (1925) Entrance to the 1925 Exposition from Place de la Concorde by Pierre Patout

Entrance to the 1925 Exposition from Place de la Concorde by Pierre Patout Polish pavilion (1925)

Polish pavilion (1925) Pavilion of the Galeries Lafayette Department Store at the 1925 Exposition

Pavilion of the Galeries Lafayette Department Store at the 1925 Exposition.jpg.webp) The Hotel du Collectionneur, pavilion of the furniture manufacturer Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann, designed by Pierre Patout.

The Hotel du Collectionneur, pavilion of the furniture manufacturer Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann, designed by Pierre Patout..jpg.webp) Salon of the Hôtel du Collectionneur from the 1925 International Exposition of Decorative Arts, furnished by Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann, painting by Jean Dupas, design by Pierre Patout

Salon of the Hôtel du Collectionneur from the 1925 International Exposition of Decorative Arts, furnished by Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann, painting by Jean Dupas, design by Pierre Patout

The event that marked the zenith of the style and gave it its name was the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts which took place in Paris from April to October in 1925. This was officially sponsored by the French government, and covered a site in Paris of 55 acres, running from the Grand Palais on the right bank to Les Invalides on the left bank, and along the banks of the Seine. The Grand Palais, the largest hall in the city, was filled with exhibits of decorative arts from the participating countries. There were 15,000 exhibitors from twenty different countries, including Austria, Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, Great Britain, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden, and the new Soviet Union. Germany was not invited because of tensions after the war; The United States, misunderstanding the purpose of the exhibit, declined to participate. The event was visited by sixteen million people during its seven-month run. The rules of the exhibition required that all work be modern; no historical styles were allowed. The main purpose of the Exhibit was to promote the French manufacturers of luxury furniture, porcelain, glass, metalwork, textiles, and other decorative products. To further promote the products, all the major Paris department stores, and major designers had their own pavilions. The Exposition had a secondary purpose in promoting products from French colonies in Africa and Asia, including ivory and exotic woods.

The Hôtel du Collectionneur was a popular attraction at the Exposition; it displayed the new furniture designs of Emile-Jacques Ruhlmann, as well as Art Deco fabrics, carpets, and a painting by Jean Dupas. The interior design followed the same principles of symmetry and geometric forms which set it apart from Art Nouveau, and bright colours, fine craftsmanship rare and expensive materials which set it apart from the strict functionality of the Modernist style. While most of the pavilions were lavishly decorated and filled with hand-made luxury furniture, two pavilions, those of the Soviet Union and Pavilion de L'Esprit Nouveau, built by the magazine of that name run by Le Corbusier, were built in an austere style with plain white walls and no decoration; they were among the earliest examples of modernist architecture.[69]

Skyscrapers

The American Radiator Building, New York City, N.Y., by Raymond Hood (1924)

The American Radiator Building, New York City, N.Y., by Raymond Hood (1924) Chrysler Building, New York City, by William Van Alen (1930)

Chrysler Building, New York City, by William Van Alen (1930)_in_flight_over_Manhattan%252C_circa_1931-1933.jpg.webp) New York City's skyline (c. 1931–33)

New York City's skyline (c. 1931–33) Crown of the General Electric Building (also known as 570 Lexington Avenue), New York City, by Cross & Cross (1933)

Crown of the General Electric Building (also known as 570 Lexington Avenue), New York City, by Cross & Cross (1933) 30 Rockefeller Plaza, New York City, by Raymond Hood (1933)

30 Rockefeller Plaza, New York City, by Raymond Hood (1933).jpg.webp) Empire State Building, New York City, by Shreve, Lamb & Harmon (1931)

Empire State Building, New York City, by Shreve, Lamb & Harmon (1931)

American skyscrapers marked the summit of the Art Deco style; they became the tallest and most recognizable modern buildings in the world. They were designed to show the prestige of their builders through their height, their shape, their color, and their dramatic illumination at night.[70] The American Radiator Building by Raymond Hood (1924) combined Gothic and Deco modern elements in the design of the building. Black brick on the frontage of the building (symbolizing coal) was selected to give an idea of solidity and to give the building a solid mass. Other parts of the façade were covered in gold bricks (symbolizing fire), and the entry was decorated with marble and black mirrors. Another early Art Deco skyscraper was Detroit's Guardian Building, which opened in 1929. Designed by modernist Wirt C. Rowland, the building was the first to employ stainless steel as a decorative element, and the extensive use of colored designs in place of traditional ornaments.

New York City's skyline was radically changed by the Chrysler Building in Manhattan (completed in 1930), designed by William Van Alen. It was a giant seventy-seven-floor tall advertisement for Chrysler automobiles. The top was crowned by a stainless steel spire, and was ornamented by deco "gargoyles" in the form of stainless steel radiator cap decorations. The base of the tower, thirty-three stories above the street, was decorated with colorful art deco friezes, and the lobby was decorated with art deco symbols and images expressing modernity.[71]

The Chrysler Building was soon surpassed in height by the Empire State Building by William F. Lamb (1931), in a slightly less lavish Deco style and the RCA Building (now 30 Rockefeller Plaza) by Raymond Hood (1933) which together completely changed New York City's skyline. The tops of the buildings were decorated with Art Deco crowns and spires covered with stainless steel, and, in the case of the Chrysler building, with Art Deco gargoyles modeled after radiator ornaments, while the entrances and lobbies were lavishly decorated with Art Deco sculpture, ceramics, and design. Similar buildings, though not quite as tall, soon appeared in Chicago and other large American cities. Rockefeller Center added a new design element: several tall buildings grouped around an open plaza, with a fountain in the middle.[72]

Late Art Deco

Lincoln Theater in Miami Beach, Florida, by Thomas W. Lamb (1936)

Lincoln Theater in Miami Beach, Florida, by Thomas W. Lamb (1936) The Palais de Chaillot by Louis-Hippolyte Boileau, Jacques Carlu and Léon Azéma from the 1937 Paris International Exposition

The Palais de Chaillot by Louis-Hippolyte Boileau, Jacques Carlu and Léon Azéma from the 1937 Paris International Exposition_(11872278295).jpg.webp) Stairway of the Economic and Social Council in Paris, originally the Museum of Public Works, built for the 1937 Paris International Exposition, by Auguste Perret (1937)

Stairway of the Economic and Social Council in Paris, originally the Museum of Public Works, built for the 1937 Paris International Exposition, by Auguste Perret (1937) High School in King City, California, built by Robert Stanton for the Works Progress Administration (1939)

High School in King City, California, built by Robert Stanton for the Works Progress Administration (1939)

In 1925, two different competing schools coexisted within Art Deco: the traditionalists, who had founded the Society of Decorative Artists; included the furniture designer Emile-Jacques Ruhlmann, Jean Dunand, the sculptor Antoine Bourdelle, and designer Paul Poiret; they combined modern forms with traditional craftsmanship and expensive materials. On the other side were the modernists, who increasingly rejected the past and wanted a style based upon advances in new technologies, simplicity, a lack of decoration, inexpensive materials, and mass production. The modernists founded their own organisation, The French Union of Modern Artists, in 1929. Its members included architects Pierre Chareau, Francis Jourdain, Robert Mallet-Stevens, Corbusier, and, in the Soviet Union, Konstantin Melnikov; the Irish designer Eileen Gray; the French designer Sonia Delaunay; and the jewellers Georges Fouquet and Jean Puiforcat. They fiercely attacked the traditional art deco style, which they said was created only for the wealthy, and insisted that well-constructed buildings should be available to everyone, and that form should follow function. The beauty of an object or building resided in whether it was perfectly fit to fulfil its function. Modern industrial methods meant that furniture and buildings could be mass-produced, not made by hand.[73][74]

The Art Deco interior designer Paul Follot defended Art Deco in this way: "We know that man is never content with the indispensable and that the superfluous is always needed...If not, we would have to get rid of music, flowers, and perfumes..!"[75] However, Le Corbusier was a brilliant publicist for modernist architecture; he stated that a house was simply "a machine to live in", and tirelessly promoted the idea that Art Deco was the past and modernism was the future. Le Corbusier's ideas were gradually adopted by architecture schools, and the aesthetics of Art Deco were abandoned. The same features that made Art Deco popular in the beginning, its craftsmanship, rich materials and ornament, led to its decline. The Great Depression that began in the United States in 1929, and reached Europe shortly afterwards, greatly reduced the number of wealthy clients who could pay for the furnishings and art objects. In the Depression economic climate, few companies were ready to build new skyscrapers.[34] Even the Ruhlmann firm resorted to producing pieces of furniture in series, rather than individual hand-made items. The last buildings built in Paris in the new style were the Museum of Public Works by Auguste Perret (now the French Economic, Social and Environmental Council), the Palais de Chaillot by Louis-Hippolyte Boileau, Jacques Carlu and Léon Azéma, and the Palais de Tokyo of the 1937 Paris International Exposition; they looked out at the grandiose pavilion of Nazi Germany, designed by Albert Speer, which faced the equally grandiose socialist-realist pavilion of Stalin's Soviet Union.

After World War II, the dominant architectural style became the International Style pioneered by Le Corbusier, and Mies van der Rohe. A handful of Art Deco hotels were built in Miami Beach after World War II, but elsewhere the style largely vanished, except in industrial design, where it continued to be used in automobile styling and products such as jukeboxes. In the 1960s, it experienced a modest academic revival, thanks in part to the writings of architectural historians such as Bevis Hillier. In the 1970s efforts were made in the United States and Europe to preserve the best examples of Art Deco architecture, and many buildings were restored and repurposed. Postmodern architecture, which first appeared in the 1980s, like Art Deco, often includes purely decorative features.[34][58][76][77] Deco continues to inspire designers, and is often used in contemporary fashion, jewellery, and toiletries.[78]

Painting

Detail of Time, ceiling mural in lobby of 30 Rockefeller Plaza (New York City, N.Y.), by the Spanish painter Josep Maria Sert (1941)

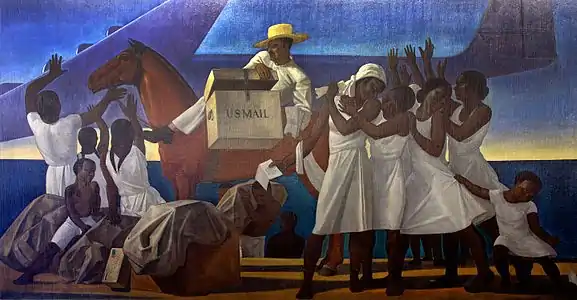

Detail of Time, ceiling mural in lobby of 30 Rockefeller Plaza (New York City, N.Y.), by the Spanish painter Josep Maria Sert (1941) Workers sorting the mail, a mural in the Ariel Rios Federal Building, Washington, D.C, by Reginald Marsh (1936)

Workers sorting the mail, a mural in the Ariel Rios Federal Building, Washington, D.C, by Reginald Marsh (1936) Art in the Tropics, mural in the William Jefferson Clinton Federal Building, Washington, D.C., by Rockwell Kent (1938)

Art in the Tropics, mural in the William Jefferson Clinton Federal Building, Washington, D.C., by Rockwell Kent (1938)

There was no section set aside for painting at the 1925 Exposition. Art deco painting was by definition decorative, designed to decorate a room or work of architecture, so few painters worked exclusively in the style, but two painters are closely associated with Art Deco. Jean Dupas painted Art Deco murals for the Bordeaux Pavilion at the 1925 Decorative Arts Exposition in Paris, and also painted the picture over the fireplace in the Maison du Collectionneur exhibit at the 1925 Exposition, which featured furniture by Ruhlmann and other prominent Art Deco designers. His murals were also prominent in the décor of the French ocean liner SS Normandie. His work was purely decorative, designed as a background or accompaniment to other elements of the décor.[79]

The other painter closely associated with the style is Tamara de Lempicka. Born in Poland, she emigrated to Paris after the Russian Revolution. She studied under Maurice Denis and André Lhote, and borrowed many elements from their styles. She painted portraits in a realistic, dynamic and colourful Art Deco style.[80]

In the 1930s a dramatic new form of Art Deco painting appeared in the United States. During the Great Depression, the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration was created to give work to unemployed artists. Many were given the task of decorating government buildings, hospitals and schools. There was no specific art deco style used in the murals; artists engaged to paint murals in government buildings came from many different schools, from American regionalism to social realism; they included Reginald Marsh, Rockwell Kent and the Mexican painter Diego Rivera. The murals were Art Deco because they were all decorative and related to the activities in the building or city where they were painted: Reginald Marsh and Rockwell Kent both decorated U.S. postal buildings, and showed postal employees at work while Diego Rivera depicted automobile factory workers for the Detroit Institute of Arts. Diego Rivera's mural Man at the Crossroads (1933) for 30 Rockefeller Plaza featured an unauthorized portrait of Lenin.[81][82] When Rivera refused to remove Lenin, the painting was destroyed and a new mural was painted by the Spanish artist Josep Maria Sert.[83][84][85]

Sculpture

Monumental and public sculpture

Aluminum statue of Ceres by John Storrs atop the Chicago Board of Trade Building, Chicago, Illinois (1930)

Aluminum statue of Ceres by John Storrs atop the Chicago Board of Trade Building, Chicago, Illinois (1930) The gilded bronze Prometheus at the Rockefeller Center (New York City, N.Y.), by Paul Manship (1934), a stylized Art Deco update of classical sculpture (1936)

The gilded bronze Prometheus at the Rockefeller Center (New York City, N.Y.), by Paul Manship (1934), a stylized Art Deco update of classical sculpture (1936) Portal decoration Wisdom by Lee Lawrie at the Rockefeller Center (1933)

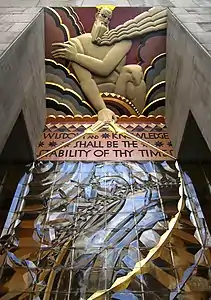

Portal decoration Wisdom by Lee Lawrie at the Rockefeller Center (1933) Lee Lawrie, 1936–37, Atlas statue, in front of the Rockefeller Center (installed 1937)

Lee Lawrie, 1936–37, Atlas statue, in front of the Rockefeller Center (installed 1937) Man Controlling Trade by Michael Lantz at the Federal Trade Commission building, Washington, D.C. (1942)

Man Controlling Trade by Michael Lantz at the Federal Trade Commission building, Washington, D.C. (1942) Mail Delivery East, by Edmond Amateis, one of four bas-relief sculptures on the Nix Federal Building, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (1937)

Mail Delivery East, by Edmond Amateis, one of four bas-relief sculptures on the Nix Federal Building, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (1937) Ralph Stackpole's sculpture group over the door of the San Francisco Stock Exchange, San Francisco, California (1930)

Ralph Stackpole's sculpture group over the door of the San Francisco Stock Exchange, San Francisco, California (1930) Aerial between Wisdom and Gaiety by Eric Gill, façade of BBC Broadcasting House, London, UK (1932)

Aerial between Wisdom and Gaiety by Eric Gill, façade of BBC Broadcasting House, London, UK (1932) Christ the Redeemer by Paul Landowski (1931), soapstone, Corcovado Mountain, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Christ the Redeemer by Paul Landowski (1931), soapstone, Corcovado Mountain, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Sculpture was a very common and integral feature of Art Deco architecture. In France, allegorical bas-reliefs representing dance and music by Antoine Bourdelle decorated the earliest Art Deco landmark in Paris, the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, in 1912. The 1925 Exposition had major sculptural works placed around the site, pavilions were decorated with sculptural friezes, and several pavilions devoted to smaller studio sculpture. In the 1930s, a large group of prominent sculptors made works for the 1937 Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne at Chaillot. Alfred Janniot made the relief sculptures on the façade of the Palais de Tokyo. The Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, and the esplanade in front of the Palais de Chaillot, facing the Eiffel Tower, was crowded with new statuary by Charles Malfray, Henry Arnold, and many others.[86]

Public art deco sculpture was almost always representational, usually of heroic or allegorical figures related to the purpose of the building or room. The themes were usually selected by the patrons, not the artist. Abstract sculpture for decoration was extremely rare.[87][88]

In the United States, the most prominent Art Deco sculptor for public art was Paul Manship, who updated classical and mythological subjects and themes in an Art Deco style. His most famous work was the statue of Prometheus at Rockefeller Center in New York City, a 20th-century adaptation of a classical subject. Other important works for Rockefeller Center were made by Lee Lawrie, including the sculptural façade and the Atlas statue.

During the Great Depression in the United States, many sculptors were commissioned to make works for the decoration of federal government buildings, with funds provided by the WPA, or Works Progress Administration. They included sculptor Sidney Biehler Waugh, who created stylized and idealized images of workers and their tasks for federal government office buildings.[89] In San Francisco, Ralph Stackpole provided sculpture for the façade of the new San Francisco Stock Exchange building. In Washington D.C., Michael Lantz made works for the Federal Trade Commission building.

In Britain, Deco public statuary was made by Eric Gill for the BBC Broadcasting House, while Ronald Atkinson decorated the lobby of the former Daily Express Building in London (1932).

One of the best known and certainly the largest public Art Deco sculpture is the Christ the Redeemer by the French sculptor Paul Landowski, completed between 1922 and 1931, located on a mountain top overlooking Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Studio sculpture

_limestone%252C_60_cm%252C_Kr%C3%B6ller-M%C3%BCller_Museum%252C_Otterlo%252C_Holland.tiff.jpg.webp) Tête (front and side view), limestone, by Joseph Csaky (c. 1920) (Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands)

Tête (front and side view), limestone, by Joseph Csaky (c. 1920) (Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands) The Hunter by Pierre Le Faguays (1920s)

The Hunter by Pierre Le Faguays (1920s) Bronze nude of a dancer on an onyx plinth by Josef Lorenzl (c. 1925)

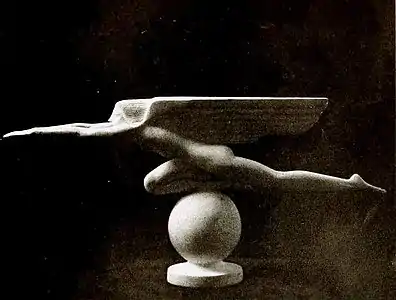

Bronze nude of a dancer on an onyx plinth by Josef Lorenzl (c. 1925) Speed, a design for a radiator ornament by Harriet Whitney Frishmuth (1925)

Speed, a design for a radiator ornament by Harriet Whitney Frishmuth (1925) The Flight of Europa, bronze with gold leaf, by Paul Manship (1925) (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City, N.Y.)

The Flight of Europa, bronze with gold leaf, by Paul Manship (1925) (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City, N.Y.) Tânără (Girl), bronze, ivory and onyx, by Demétre Chiparus (c. 1925)

Tânără (Girl), bronze, ivory and onyx, by Demétre Chiparus (c. 1925) Dansatoare (Dancer), bronze and ivory, by Chiparus (c. 1925)

Dansatoare (Dancer), bronze and ivory, by Chiparus (c. 1925)

Many early Art Deco sculptures were small, designed to decorate salons. One genre of this sculpture was called the Chryselephantine statuette, named for a style of ancient Greek temple statues made of gold and ivory. They were sometimes made of bronze, or sometimes with much more lavish materials, such as ivory, onyx, alabaster, and gold leaf.

One of the best-known Art Deco salon sculptors was the Romanian-born Demétre Chiparus, who produced colourful small sculptures of dancers. Other notable salon sculptors included Ferdinand Preiss, Josef Lorenzl, Alexander Kelety, Dorothea Charol and Gustav Schmidtcassel.[90] Another important American sculptor in the studio format was Harriet Whitney Frishmuth, who had studied with Auguste Rodin in Paris.

Pierre Le Paguays was a prominent Art Deco studio sculptor, whose work was shown at the 1925 Exposition. He worked with bronze, marble, ivory, onyx, gold, alabaster and other precious materials.[91]

François Pompon was a pioneer of modern stylised animalier sculpture. He was not fully recognised for his artistic accomplishments until the age of 67 at the Salon d'Automne of 1922 with the work Ours blanc, also known as The White Bear, now in the Musée d'Orsay in Paris.[92]

Parallel with these Art Deco sculptors, more avant-garde and abstract modernist sculptors were at work in Paris and New York City. The most prominent were Constantin Brâncuși, Joseph Csaky, Alexander Archipenko, Henri Laurens, Jacques Lipchitz, Gustave Miklos, Jean Lambert-Rucki, Jan et Joël Martel, Chana Orloff and Pablo Gargallo.[93]

Graphic arts

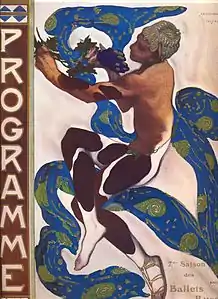

Programme for the Ballets Russes by Léon Bakst (1912)

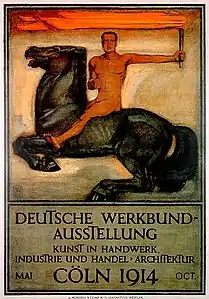

Programme for the Ballets Russes by Léon Bakst (1912) Peter Behrens, Deutscher Werkbund exhibition poster (1914)

Peter Behrens, Deutscher Werkbund exhibition poster (1914) A Vanity Fair cover by Georges Lepape (1919)

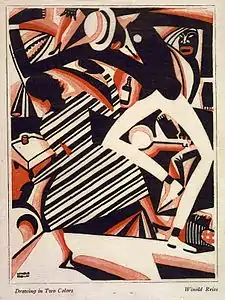

A Vanity Fair cover by Georges Lepape (1919) Interpretation of Harlem Jazz I by Winold Reiss (c.1920)

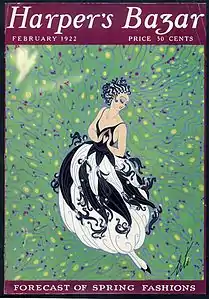

Interpretation of Harlem Jazz I by Winold Reiss (c.1920) Cover of Harper's Bazaar by Erté (1922)

Cover of Harper's Bazaar by Erté (1922) London Underground poster by Horace Taylor (1924)

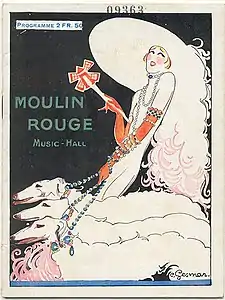

London Underground poster by Horace Taylor (1924) Moulin Rouge poster by Charles Gesmar (1925)

Moulin Rouge poster by Charles Gesmar (1925) Cover of the Jester of Columbia, unattributed (1931)

Cover of the Jester of Columbia, unattributed (1931)

The Art Deco style appeared early in the graphic arts, in the years just before World War I. It appeared in Paris in the posters and the costume designs of Léon Bakst for the Ballets Russes, and in the catalogues of the fashion designers Paul Poiret.[94] The illustrations of Georges Barbier, and Georges Lepape and the images in the fashion magazine La Gazette du bon ton perfectly captured the elegance and sensuality of the style. In the 1920s, the look changed; the fashions stressed were more casual, sportive and daring, with the woman models usually smoking cigarettes. American fashion magazines such as Vogue, Vanity Fair and Harper's Bazaar quickly picked up the new style and popularized it in the United States. It also influenced the work of American book illustrators such as Rockwell Kent. In Germany, the most famous poster artist of the period was Ludwig Hohlwein, who created colourful and dramatic posters for music festivals, beers, and, late in his career, for the Nazi Party.[95]

During the Art Nouveau period, posters usually advertised theatrical products or cabarets. In the 1920s, travel posters, made for steamship lines and airlines, became extremely popular. The style changed notably in the 1920s, to focus attention on the product being advertised. The images became simpler, precise, more linear, more dynamic, and were often placed against a single color background. In France, popular Art Deco designers included, Charles Loupot and Paul Colin, who became famous for his posters of American singer and dancer Josephine Baker. Jean Carlu designed posters for Charlie Chaplin movies, soaps, and theatres; in the late 1930s he emigrated to the United States, where, during the World War, he designed posters to encourage war production. The designer Charles Gesmar became famous making posters for the singer Mistinguett and for Air France. Among the best known French Art Deco poster designers was Cassandre, who made the celebrated poster of the ocean liner SS Normandie in 1935.[95]

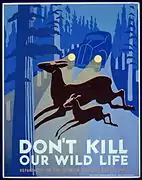

In the 1930s a new genre of posters appeared in the United States during the Great Depression. The Federal Art Project hired American artists to create posters to promote tourism and cultural events.

Architecture

La Samaritaine department store in Paris, France, by Henri Sauvage (1925–28)

La Samaritaine department store in Paris, France, by Henri Sauvage (1925–28)_edit1.jpg.webp) Los Angeles City Hall by John Parkinson, John C. Austin, and Albert C. Martin Sr. (1928)

Los Angeles City Hall by John Parkinson, John C. Austin, and Albert C. Martin Sr. (1928)%252C_1929.jpg.webp)

Interior of the Palacio de Bellas Artes (Palace of Fine Arts) in Mexico City, Mexico (1934)

Interior of the Palacio de Bellas Artes (Palace of Fine Arts) in Mexico City, Mexico (1934) Entrance of the Villa Empain in Brussels, Belgium (1930–34)

Entrance of the Villa Empain in Brussels, Belgium (1930–34) National Diet Building in Tokyo, Japan (1936)

National Diet Building in Tokyo, Japan (1936) Mayakovskaya Metro Station in Moscow, Russia (1936)

Mayakovskaya Metro Station in Moscow, Russia (1936).jpg.webp) Detail of Bulevardul Dacia no. 89 in Bucharest, by unknown architect (1930s)

Detail of Bulevardul Dacia no. 89 in Bucharest, by unknown architect (1930s)

The architectural style of art deco made its debut in Paris in 1903–04, with the construction of two apartment buildings in Paris, one by Auguste Perret on rue Benjamin Franklin and the other on rue Trétaigne by Henri Sauvage. The two young architects used reinforced concrete for the first time in Paris residential buildings; the new buildings had clean lines, rectangular forms, and no decoration on the facades; they marked a clean break with the art nouveau style.[96] Between 1910 and 1913, Perret used his experience in concrete apartment buildings to construct the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, 15 avenue Montaigne. Between 1925 and 1928 Sauvage constructed the new art deco façade of La Samaritaine department store in Paris.[97]

After the First World War, art deco buildings of steel and reinforced concrete began to appear in large cities across Europe and the United States. In the United States the style was most commonly used for office buildings, government buildings, cinemas, and railroad stations. It sometimes was combined with other styles; Los Angeles City Hall combined Art Deco with a roof based on the ancient Greek Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, while the Los Angeles railroad station combined Deco with Spanish mission architecture. Art Deco elements also appeared in engineering projects, including the towers of the Golden Gate Bridge and the intake towers of Hoover Dam. In the 1920s and 1930s it became a truly international style, with examples including the Palacio de Bellas Artes (Palace of Fine Arts) in Mexico City by Federico Mariscal, the Mayakovskaya Metro Station in Moscow and the National Diet Building in Tokyo by Watanabe Fukuzo.

The Art Deco style was not limited to buildings on land; the ocean liner SS Normandie, whose first voyage was in 1935, featured Art Deco design, including a dining room whose ceiling and decoration were made of glass by Lalique.[98]

"Cathedrals of Commerce"

The Fisher Building in Detroit, Michigan, by Joseph Nathaniel French (1928)

The Fisher Building in Detroit, Michigan, by Joseph Nathaniel French (1928).jpg.webp) Lower lobby of the Guardian Building in Detroit by Wirt Rowland (1929)

Lower lobby of the Guardian Building in Detroit by Wirt Rowland (1929) Lobby of 450 Sutter Street in San Francisco, California, by Timothy Pflueger (1929)

Lobby of 450 Sutter Street in San Francisco, California, by Timothy Pflueger (1929) Lobby of the Chrysler Building in New York City, N.Y., by William Van Alen (1930)

Lobby of the Chrysler Building in New York City, N.Y., by William Van Alen (1930) Interior door in the Chrysler Building (1930)

Interior door in the Chrysler Building (1930) Ceiling and chandelier detail on the lobby of the Carew Tower in Cincinnati, Ohio, by Walter W. Ahlschlager (1930)

Ceiling and chandelier detail on the lobby of the Carew Tower in Cincinnati, Ohio, by Walter W. Ahlschlager (1930)_(3678836375).jpg.webp) Salon d'Afrique of the Palais de la Porte Dorée with furnitures by Jacques-Emile Ruhlmann and frescos by Louis Bouquet (1931)

Salon d'Afrique of the Palais de la Porte Dorée with furnitures by Jacques-Emile Ruhlmann and frescos by Louis Bouquet (1931) Foyer of the Tuschinski Theatre in Amsterdam, Netherlands, by Hijman Louis de Jong (1921)

Foyer of the Tuschinski Theatre in Amsterdam, Netherlands, by Hijman Louis de Jong (1921)

The grand showcases of American Art deco interior design were the lobbies of government buildings, theaters, and particularly office buildings. Interiors were extremely colorful and dynamic, combining sculpture, murals, and ornate geometric design in marble, glass, ceramics and stainless steel. An early example was the Fisher Building in Detroit, by Joseph Nathaniel French; the lobby was highly decorated with sculpture and ceramics. The Guardian Building (originally the Union Trust Building) in Detroit, by Wirt Rowland (1929), decorated with red and black marble and brightly colored ceramics, highlighted by highly polished steel elevator doors and counters. The sculptural decoration installed in the walls illustrated the virtues of industry and saving; the building was immediately termed the "Cathedral of Commerce". The Medical and Dental Building called 450 Sutter Street in San Francisco by Timothy Pflueger was inspired by Mayan architecture, in a highly stylized form; it used pyramid shapes, and the interior walls were covered with highly stylized rows of hieroglyphs.[99]

In France, the best example of an Art Deco interior during this period was the Palais de la Porte Dorée (1931) by Albert Laprade, Léon Jaussely and Léon Bazin. The building (now the National Museum of Immigration, with an aquarium in the basement) was built for the Paris Colonial Exposition of 1931, to celebrate the people and products of French colonies. The exterior façade was entirely covered with sculpture, and the lobby created an Art Deco harmony with a wood parquet floor in a geometric pattern, a mural depicting the people of French colonies; and a harmonious composition of vertical doors and horizontal balconies.[99]

Movie palaces

Grauman's Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood (Los Angeles), California (1922)

Grauman's Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood (Los Angeles), California (1922) Four-story high grand lobby of the Paramount Theatre in Oakland, California (1932)

Four-story high grand lobby of the Paramount Theatre in Oakland, California (1932) Auditorium and stage of Radio City Music Hall in New York City, N.Y. (1932)

Auditorium and stage of Radio City Music Hall in New York City, N.Y. (1932) Grand Rex in Paris, France (1932)

Grand Rex in Paris, France (1932) Gaumont State Cinema in London, UK (1937)

Gaumont State Cinema in London, UK (1937) The Paramount in Shanghai, China (1933)

The Paramount in Shanghai, China (1933).jpg.webp) The Tuschinski Theatre in Amsterdam, The Netherlands (1921)

The Tuschinski Theatre in Amsterdam, The Netherlands (1921)

Many of the best surviving examples of Art Deco are cinemas built in the 1920s and 1930s. The Art Deco period coincided with the conversion of silent films to sound, and movie companies built large display destinations in major cities to capture the huge audience that came to see movies. Movie palaces in the 1920s often combined exotic themes with art deco style; Grauman's Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood (1922) was inspired by ancient Egyptian tombs and pyramids, while the Fox Theater in Bakersfield, California attached a tower in California Mission style to an Art Deco hall. The largest of all is Radio City Music Hall in New York City, which opened in 1932. Originally designed as theatrical performance space, it quickly transformed into a cinema, which could seat 6,015 customers. The interior design by Donald Deskey used glass, aluminum, chrome, and leather to create a visual escape from reality. The Paramount Theatre in Oakland, California, by Timothy Pflueger, had a colorful ceramic façade, a lobby four stories high, and separate Art Deco smoking rooms for gentlemen and ladies. Similar grand palaces appeared in Europe. The Grand Rex in Paris (1932), with its imposing tower, was the largest cinema in Europe after the 6,000 seats of the Gaumont-Palace (1931-1973). The Gaumont State Cinema in London (1937) had a tower modelled on the Empire State building, covered with cream ceramic tiles and an interior in an Art Deco-Italian Renaissance style. The Paramount Theatre in Shanghai, China (1933) was originally built as a dance hall called The gate of 100 pleasures; it was converted to a cinema after the Communist Revolution in 1949, and now is a ballroom and disco. In the 1930s Italian architects built a small movie palace, the Cinema Impero, in Asmara in what is now Eritrea. Today, many of the movie theatres have been subdivided into multiplexes, but others have been restored and are used as cultural centres in their communities.[100]

Streamline Moderne

The nautical-style rounded corner of Broadcasting House in London, UK (1931)

The nautical-style rounded corner of Broadcasting House in London, UK (1931) Paris' building in the Paquebot or ocean liner style, 3 boulevard Victor, by Pierre Patout (1935)

Paris' building in the Paquebot or ocean liner style, 3 boulevard Victor, by Pierre Patout (1935) Pan-Pacific Auditorium in Los Angeles, California (1936)

Pan-Pacific Auditorium in Los Angeles, California (1936) The Marine Air Terminal at La Guardia Airport (1937) was New York City's terminal for the flights of Pan Am Clipper flying boats to Europe

The Marine Air Terminal at La Guardia Airport (1937) was New York City's terminal for the flights of Pan Am Clipper flying boats to Europe The Hoover Building canteen in Perivale in London's suburbs, by Wallis, Gilbert and Partners (1938)

The Hoover Building canteen in Perivale in London's suburbs, by Wallis, Gilbert and Partners (1938) Former Belgian National Institute of Radio Broadcasting in Ixelles (Brussels), Belgium (1938)

Former Belgian National Institute of Radio Broadcasting in Ixelles (Brussels), Belgium (1938) The building at East Finchley tube station in London (1939)

The building at East Finchley tube station in London (1939) The Ford Pavilion at the 1939 New York World's Fair

The Ford Pavilion at the 1939 New York World's Fair Streamline Moderne church, First Church of Deliverance in Chicago, Illinois, by Walter T. Bailey (1939). Towers added in 1948.

Streamline Moderne church, First Church of Deliverance in Chicago, Illinois, by Walter T. Bailey (1939). Towers added in 1948.

In the late 1930s, a new variety of Art Deco architecture became common; it was called Streamline Moderne or simply Streamline, or, in France, the Style Paquebot, or Ocean Liner style. Buildings in the style had rounded corners and long horizontal lines; they were built of reinforced concrete, and were almost always white; and they sometimes had nautical features, such as railings and portholes that resembled those on a ship. The rounded corner was not entirely new; it had appeared in Berlin in 1923 in the Mossehaus by Erich Mendelsohn, and later in the Hoover Building, an industrial complex in the London suburb of Perivale. In the United States, it became most closely associated with transport; Streamline moderne was rare in office buildings, but was often used for bus stations and airport terminals, such as the terminal at La Guardia airport in New York City that handled the first transatlantic flights, via the PanAm Clipper flying boats; and in roadside architecture, such as gas stations and diners. In the late 1930s a series of diners, modelled upon streamlined railroad cars, were produced and installed in towns in New England; at least two examples still remain and are now registered historic buildings.[101]

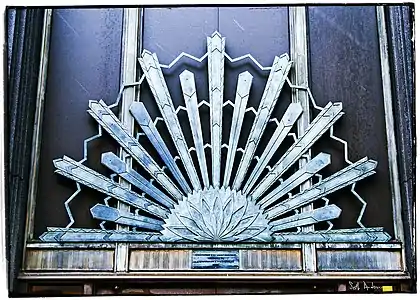

Decoration and motifs

Iron fireplace screen, Rose Iron Works (Cleveland, Ohio) (1930)

Iron fireplace screen, Rose Iron Works (Cleveland, Ohio) (1930).jpg.webp) Elevator doors of the Chrysler Building (New York City, N.Y.), by William Van Alen (1927–30)

Elevator doors of the Chrysler Building (New York City, N.Y.), by William Van Alen (1927–30)

Detail of mosaic facade of Paramount Theatre (Oakland, California) (1931)

Detail of mosaic facade of Paramount Theatre (Oakland, California) (1931)

Decoration in the Art Deco period went through several distinct phases. Between 1910 and 1920, as Art Nouveau was exhausted, design styles saw a return to tradition, particularly in the work of Paul Iribe. In 1912 André Vera published an essay in the magazine L'Art Décoratif calling for a return to the craftsmanship and materials of earlier centuries, and using a new repertoire of forms taken from nature, particularly baskets and garlands of fruit and flowers. A second tendency of Art Deco, also from 1910 to 1920, was inspired by the bright colours of the artistic movement known as the Fauves and by the colourful costumes and sets of the Ballets Russes. This style was often expressed with exotic materials such as sharkskin, mother of pearl, ivory, tinted leather, lacquered and painted wood, and decorative inlays on furniture that emphasized its geometry. This period of the style reached its high point in the 1925 Paris Exposition of Decorative Arts. In the late 1920s and the 1930s, the decorative style changed, inspired by new materials and technologies. It became sleeker and less ornamental. Furniture, like architecture, began to have rounded edges and to take on a polished, streamlined look, taken from the streamline modern style. New materials, such as nickel or chrome-plated steel, aluminium and bakelite, an early form of plastic, began to appear in furniture and decoration.[102]

Throughout the Art Deco period, and particularly in the 1930s, the motifs of the décor expressed the function of the building. Theatres were decorated with sculpture which illustrated music, dance, and excitement; power companies showed sunrises, the Chrysler building showed stylized hood ornaments; The friezes of Palais de la Porte Dorée at the 1931 Paris Colonial Exposition showed the faces of the different nationalities of French colonies. The Streamline style made it appear that the building itself was in motion. The WPA murals of the 1930s featured ordinary people; factory workers, postal workers, families and farmers, in place of classical heroes.[103]

Furniture

Chair by Paul Follot (1912–14)

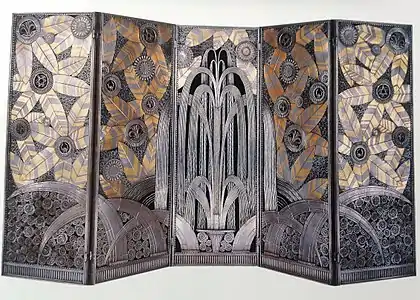

Chair by Paul Follot (1912–14).jpg.webp) Armchair by Louis Süe (1912) and painted screen by André Mare (1920)

Armchair by Louis Süe (1912) and painted screen by André Mare (1920).jpg.webp) Dressing table and chair of marble and encrusted, lacquered, and gilded wood by Follot (1919–20)

Dressing table and chair of marble and encrusted, lacquered, and gilded wood by Follot (1919–20)._Corner_Cabinet%252C_ca._1923..jpg.webp) Corner cabinet of Mahogany with rose basket design of inlaid ivory by Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann (1923)

Corner cabinet of Mahogany with rose basket design of inlaid ivory by Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann (1923)_(2132077838).jpg.webp) Cabinet by Ruhlmann (1926)

Cabinet by Ruhlmann (1926)_(5469658728).jpg.webp) Cabinet design by Ruhlmann

Cabinet design by Ruhlmann Cabinet covered with shagreen or sharkskin by André Groult (1925)

Cabinet covered with shagreen or sharkskin by André Groult (1925) Furniture by Gio Ponti (1927)

Furniture by Gio Ponti (1927) Desk of an administrator, by Michel Roux-Spitz for the 1930 Salon of Decorative Artists

Desk of an administrator, by Michel Roux-Spitz for the 1930 Salon of Decorative Artists An Art Deco club chair (1930s)

An Art Deco club chair (1930s)_(2132078468).jpg.webp) Late Art Deco furniture and rug by Jules Leleu (1930s)

Late Art Deco furniture and rug by Jules Leleu (1930s) A Waterfall style buffet table

A Waterfall style buffet table

French furniture from 1910 until the early 1920s was largely an updating of French traditional furniture styles, and the art nouveau designs of Louis Majorelle, Charles Plumet and other manufacturers. French furniture manufacturers felt threatened by the growing popularity of German manufacturers and styles, particularly the Biedermeier style, which was simple and clean-lined. The French designer Frantz Jourdain, the President of the Paris Salon d'Automne, invited designers from Munich to participate in the 1910 Salon. French designers saw the new German style, and decided to meet the German challenge. The French designers decided to present new French styles in the Salon of 1912. The rules of the Salon indicated that only modern styles would be permitted. All of the major French furniture designers took part in Salon: Paul Follot, Paul Iribe, Maurice Dufrêne, André Groult, André Mare and Louis Suë took part, presenting new works that updated the traditional French styles of Louis XVI and Louis Philippe with more angular corners inspired by Cubism and brighter colours inspired by Fauvism and the Nabis.[104]

The painter André Mare and furniture designer Louis Süe both participated the 1912 Salon. After the war the two men joined to form their own company, formally called the Compagnie des Arts Française, but usually known simply as Suë and Mare. Unlike the prominent art nouveau designers like Louis Majorelle, who personally designed every piece, they assembled a team of skilled craftsmen and produced complete interior designs, including furniture, glassware, carpets, ceramics, wallpaper and lighting. Their work featured bright colors and furniture and fine woods, such as ebony encrusted with mother of pearl, abalone and silvered metal to create bouquets of flowers. They designed everything from the interiors of ocean liners to perfume bottles for the label of Jean Patou.The firm prospered in the early 1920s, but the two men were better craftsmen than businessmen. The firm was sold in 1928, and both men left.[105]

The most prominent furniture designer at the 1925 Decorative Arts Exposition was Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann, from Alsace. He first exhibited his works at the 1913 Autumn Salon, then had his own pavilion, the "House of the Rich Collector", at the 1925 Exposition. He used only most rare and expensive materials, including ebony, mahogany, rosewood, ambon and other exotic woods, decorated with inlays of ivory, tortoise shell, mother of pearl, Little pompoms of silk decorated the handles of drawers of the cabinets.[106] His furniture was based upon 18th-century models, but simplified and reshaped. In all of his work, the interior structure of the furniture was completely concealed. The framework usually of oak, was completely covered with an overlay of thin strips of wood, then covered by a second layer of strips of rare and expensive woods. This was then covered with a veneer and polished, so that the piece looked as if it had been cut out of a single block of wood. Contrast to the dark wood was provided by inlays of ivory, and ivory key plates and handles. According to Ruhlmann, armchairs had to be designed differently according to the functions of the rooms where they appeared; living room armchairs were designed to be welcoming, office chairs comfortable, and salon chairs voluptuous. Only a small number of pieces of each design of furniture was made, and the average price of one of his beds or cabinets was greater than the price of an average house.[107]

Jules Leleu was a traditional furniture designer who moved smoothly into Art Deco in the 1920s; he designed the furniture for the dining room of the Élysée Palace, and for the first-class cabins of the steamship Normandie. his style was characterized by the use of ebony, Macassar wood, walnut, with decoration of plaques of ivory and mother of pearl. He introduced the style of lacquered art deco furniture in the late 1920s, and in the late 1930s introduced furniture made of metal with panels of smoked glass.[108] In Italy, the designer Gio Ponti was famous for his streamlined designs.

The costly and exotic furniture of Ruhlmann and other traditionalists infuriated modernists, including the architect Le Corbusier, causing him to write a famous series of articles denouncing the arts décoratif style. He attacked furniture made only for the rich, and called upon designers to create furniture made with inexpensive materials and modern style, which ordinary people could afford. He designed his own chairs, created to be inexpensive and mass-produced.[109]

In the 1930s, furniture designs adapted to the form, with smoother surfaces and curved forms. The masters of the late style included Donald Deskey, who was one of the most influential designers; he created the interior of the Radio City Music Hall. He used a mixture of traditional and very modern materials, including aluminium, chrome, and bakelite, an early form of plastic.[110] Other masters of art deco furniture of the 1930s in the United States included Gilbert Rohde, Warren McArthur, Kem Weber, and Wolfgang Hoffman.

The Waterfall style was popular in the 1930s and 1940s, the most prevalent Art Deco form of furniture at the time. Pieces were typically of plywood finished with blond veneer and with rounded edges, resembling a waterfall.[111]

Design

Parker Duofold desk set (c. 1930)

Parker Duofold desk set (c. 1930) "Beau Brownie" camera, design by Walter Dorwin Teague for Eastman Kodak (1930)

"Beau Brownie" camera, design by Walter Dorwin Teague for Eastman Kodak (1930) Philips Art Deco radio set (1931)

Philips Art Deco radio set (1931)_Table_Radio%252C_Model_37-610T%252C_Broadcast_%2526_Short_Wave_Bands%252C_Art_Deco_Design%252C_5_Vacuum_Tubes%252C_Walnut_Veneer_Cabinet%252C_Circa_1937_(15351304051).jpg.webp) Philco Table Radio (c. 1937)

Philco Table Radio (c. 1937) Electrolux Vacuum cleaner (1937)

Electrolux Vacuum cleaner (1937) New York's 20th Century Limited Hudson 4-6-4 Streamlined Locomotive (c. 1939)

New York's 20th Century Limited Hudson 4-6-4 Streamlined Locomotive (c. 1939) Chrysler Airflow sedan, designed by Carl Breer (1934)

Chrysler Airflow sedan, designed by Carl Breer (1934) 1937 Cord automobile model 812, designed in 1935 by Gordon M. Buehrig and staff

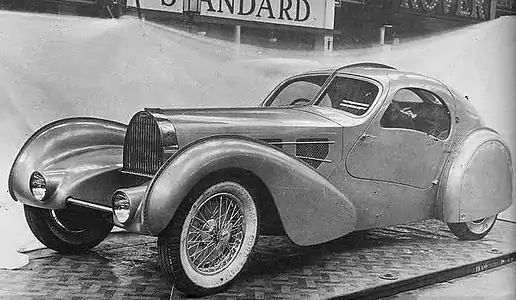

1937 Cord automobile model 812, designed in 1935 by Gordon M. Buehrig and staff Bugatti Aérolithe (1936)

Bugatti Aérolithe (1936)

Streamline was a variety of Art Deco which emerged during the mid-1930s. It was influenced by modern aerodynamic principles developed for aviation and ballistics to reduce aerodynamic drag at high velocities. The bullet shapes were applied by designers to cars, trains, ships, and even objects not intended to move, such as refrigerators, gas pumps, and buildings.[60] One of the first production vehicles in this style was the Chrysler Airflow of 1933. It was unsuccessful commercially, but the beauty and functionality of its design set a precedent; meant modernity. It continued to be used in car design well after World War II.[112][113][114][115]

New industrial materials began to influence the design of cars and household objects. These included aluminium, chrome, and bakelite, an early form of plastic. Bakelite could be easily moulded into different forms, and soon was used in telephones, radios and other appliances.

_interior.jpg.webp)

Ocean liners also adopted a style of Art Deco, known in French as the Style Paquebot, or "Ocean Liner Style". The most famous example was the SS Normandie, which made its first transatlantic trip in 1935. It was designed particularly to bring wealthy Americans to Paris to shop. The cabins and salons featured the latest Art Deco furnishings and decoration. The Grand Salon of the ship, which was the restaurant for first-class passengers, was bigger than the Hall of Mirrors of the Palace of Versailles. It was illuminated by electric lights within twelve pillars of Lalique crystal; thirty-six matching pillars lined the walls. This was one of the earliest examples of illumination being directly integrated into architecture. The style of ships was soon adapted to buildings. A notable example is found on the San Francisco waterfront, where the Maritime Museum building, built as a public bath in 1937, resembles a ferryboat, with ship railings and rounded corners. The Star Ferry Terminal in Hong Kong also used a variation of the style.[34]

Textiles and fashion

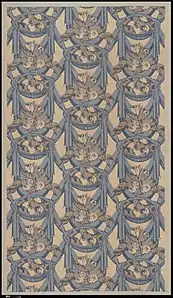

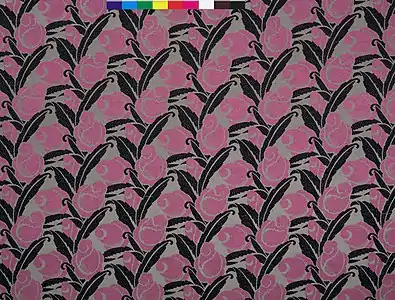

Textile design Abundance by André Mare, (1911) (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, USA)

Textile design Abundance by André Mare, (1911) (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, USA) Rose Pattern Textiles designed by Mare (c. 1919) (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Rose Pattern Textiles designed by Mare (c. 1919) (Metropolitan Museum of Art) Rose Mousse pattern for upholstery, cotton and silk (1920) (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Rose Mousse pattern for upholstery, cotton and silk (1920) (Metropolitan Museum of Art) Design of birds from Les Ateliers de Martine by Paul Iribe (1918)

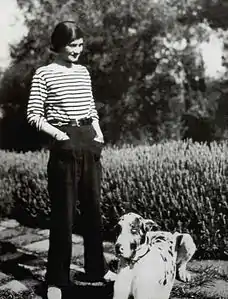

Design of birds from Les Ateliers de Martine by Paul Iribe (1918)