Art

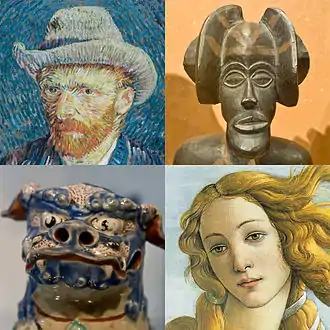

Art is a diverse range of human activity, and resulting product, that involves creative or imaginative talent expressive of technical proficiency, beauty, emotional power, or conceptual ideas.[1][2][3]

There is no generally agreed definition of what constitutes art,[4][5][6] and its interpretation has varied greatly throughout history and across cultures. The three classical branches of visual art are painting, sculpture, and architecture.[7] Theatre, dance, and other performing arts, as well as literature, music, film and other media such as interactive media, are included in a broader definition of the arts.[1][8] Until the 17th century, art referred to any skill or mastery and was not differentiated from crafts or sciences. In modern usage after the 17th century, where aesthetic considerations are paramount, the fine arts are separated and distinguished from acquired skills in general, such as the decorative or applied arts.

The nature of art and related concepts, such as creativity and interpretation, are explored in a branch of philosophy known as aesthetics.[9] The resulting artworks are studied in the professional fields of art criticism and the history of art.

Overview

In the perspective of the history of art,[10] artistic works have existed for almost as long as humankind: from early pre-historic art to contemporary art; however, some theorists think that the typical concept of "artistic works" does not fit well outside modern Western societies.[11] One early sense of the definition of art is closely related to the older Latin meaning, which roughly translates to "skill" or "craft", as associated with words such as "artisan". English words derived from this meaning include artifact, artificial, artifice, medical arts, and military arts. However, there are many other colloquial uses of the word, all with some relation to its etymology.

Over time, philosophers like Plato, Aristotle, Socrates and Kant, among others, questioned the meaning of art.[12] Several dialogues in Plato tackle questions about art: Socrates says that poetry is inspired by the muses, and is not rational. He speaks approvingly of this, and other forms of divine madness (drunkenness, eroticism, and dreaming) in the Phaedrus (265a–c), and yet in the Republic wants to outlaw Homer's great poetic art, and laughter as well. In Ion, Socrates gives no hint of the disapproval of Homer that he expresses in the Republic. The dialogue Ion suggests that Homer's Iliad functioned in the ancient Greek world as the Bible does today in the modern Christian world: as divinely inspired literary art that can provide moral guidance, if only it can be properly interpreted.[13]

With regards to the literary art and the musical arts, Aristotle considered epic poetry, tragedy, comedy, Dithyrambic poetry and music to be mimetic or imitative art, each varying in imitation by medium, object, and manner.[14] For example, music imitates with the media of rhythm and harmony, whereas dance imitates with rhythm alone, and poetry with language. The forms also differ in their object of imitation. Comedy, for instance, is a dramatic imitation of men worse than average; whereas tragedy imitates men slightly better than average. Lastly, the forms differ in their manner of imitation—through narrative or character, through change or no change, and through drama or no drama.[15] Aristotle believed that imitation is natural to mankind and constitutes one of mankind's advantages over animals.[16]

The more recent and specific sense of the word art as an abbreviation for creative art or fine art emerged in the early 17th century.[17] Fine art refers to a skill used to express the artist's creativity, or to engage the audience's aesthetic sensibilities, or to draw the audience towards consideration of more refined or finer work of art.

Within this latter sense, the word art may refer to several things: (i) a study of a creative skill, (ii) a process of using the creative skill, (iii) a product of the creative skill, or (iv) the audience's experience with the creative skill. The creative arts (art as discipline) are a collection of disciplines which produce artworks (art as objects) that are compelled by a personal drive (art as activity) and convey a message, mood, or symbolism for the perceiver to interpret (art as experience). Art is something that stimulates an individual's thoughts, emotions, beliefs, or ideas through the senses. Works of art can be explicitly made for this purpose or interpreted on the basis of images or objects. For some scholars, such as Kant, the sciences and the arts could be distinguished by taking science as representing the domain of knowledge and the arts as representing the domain of the freedom of artistic expression.[18]

Often, if the skill is being used in a common or practical way, people will consider it a craft instead of art. Likewise, if the skill is being used in a commercial or industrial way, it may be considered commercial art instead of fine art. On the other hand, crafts and design are sometimes considered applied art. Some art followers have argued that the difference between fine art and applied art has more to do with value judgments made about the art than any clear definitional difference.[19] However, even fine art often has goals beyond pure creativity and self-expression. The purpose of works of art may be to communicate ideas, such as in politically, spiritually, or philosophically motivated art; to create a sense of beauty (see aesthetics); to explore the nature of perception; for pleasure; or to generate strong emotions. The purpose may also be seemingly nonexistent.

The nature of art has been described by philosopher Richard Wollheim as "one of the most elusive of the traditional problems of human culture".[20] Art has been defined as a vehicle for the expression or communication of emotions and ideas, a means for exploring and appreciating formal elements for their own sake, and as mimesis or representation. Art as mimesis has deep roots in the philosophy of Aristotle.[21] Leo Tolstoy identified art as a use of indirect means to communicate from one person to another.[21] Benedetto Croce and R. G. Collingwood advanced the idealist view that art expresses emotions, and that the work of art therefore essentially exists in the mind of the creator.[22][23] The theory of art as form has its roots in the philosophy of Kant, and was developed in the early 20th century by Roger Fry and Clive Bell. More recently, thinkers influenced by Martin Heidegger have interpreted art as the means by which a community develops for itself a medium for self-expression and interpretation.[24] George Dickie has offered an institutional theory of art that defines a work of art as any artifact upon which a qualified person or persons acting on behalf of the social institution commonly referred to as "the art world" has conferred "the status of candidate for appreciation".[25] Larry Shiner has described fine art as "not an essence or a fate but something we have made. Art as we have generally understood it is a European invention barely two hundred years old."[26]

Art may be characterized in terms of mimesis (its representation of reality), narrative (storytelling), expression, communication of emotion, or other qualities. During the Romantic period, art came to be seen as "a special faculty of the human mind to be classified with religion and science".[27]

History

A shell engraved by Homo erectus was determined to be between 430,000 and 540,000 years old.[28] A set of eight 130,000 years old white-tailed eagle talons bear cut marks and abrasion that indicate manipulation by neanderthals, possibly for using it as jewelry.[29] A series of tiny, drilled snail shells about 75,000 years old—were discovered in a South African cave.[30] Containers that may have been used to hold paints have been found dating as far back as 100,000 years.[31]

Sculptures, cave paintings, rock paintings and petroglyphs from the Upper Paleolithic dating to roughly 40,000 years ago have been found,[32] but the precise meaning of such art is often disputed because so little is known about the cultures that produced them.

Many great traditions in art have a foundation in the art of one of the great ancient civilizations: Ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Persia, India, China, Ancient Greece, Rome, as well as Inca, Maya, and Olmec. Each of these centers of early civilization developed a unique and characteristic style in its art. Because of the size and duration of these civilizations, more of their art works have survived and more of their influence has been transmitted to other cultures and later times. Some also have provided the first records of how artists worked. For example, this period of Greek art saw a veneration of the human physical form and the development of equivalent skills to show musculature, poise, beauty, and anatomically correct proportions.[33]

In Byzantine and Medieval art of the Western Middle Ages, much art focused on the expression of subjects about biblical and religious culture, and used styles that showed the higher glory of a heavenly world, such as the use of gold in the background of paintings, or glass in mosaics or windows, which also presented figures in idealized, patterned (flat) forms. Nevertheless, a classical realist tradition persisted in small Byzantine works, and realism steadily grew in the art of Catholic Europe.[34]

Renaissance art had a greatly increased emphasis on the realistic depiction of the material world, and the place of humans in it, reflected in the corporeality of the human body, and development of a systematic method of graphical perspective to depict recession in a three-dimensional picture space.[35]

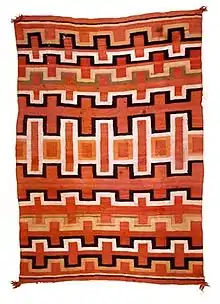

In the east, Islamic art's rejection of iconography led to emphasis on geometric patterns, calligraphy, and architecture.[37] Further east, religion dominated artistic styles and forms too. India and Tibet saw emphasis on painted sculptures and dance, while religious painting borrowed many conventions from sculpture and tended to bright contrasting colors with emphasis on outlines. China saw the flourishing of many art forms: jade carving, bronzework, pottery (including the stunning terracotta army of Emperor Qin[38]), poetry, calligraphy, music, painting, drama, fiction, etc. Chinese styles vary greatly from era to era and each one is traditionally named after the ruling dynasty. So, for example, Tang dynasty paintings are monochromatic and sparse, emphasizing idealized landscapes, but Ming dynasty paintings are busy and colorful, and focus on telling stories via setting and composition.[39] Japan names its styles after imperial dynasties too, and also saw much interplay between the styles of calligraphy and painting. Woodblock printing became important in Japan after the 17th century.[40]

The western Age of Enlightenment in the 18th century saw artistic depictions of physical and rational certainties of the clockwork universe, as well as politically revolutionary visions of a post-monarchist world, such as Blake's portrayal of Newton as a divine geometer,[41] or David's propagandistic paintings. This led to Romantic rejections of this in favor of pictures of the emotional side and individuality of humans, exemplified in the novels of Goethe. The late 19th century then saw a host of artistic movements, such as academic art, Symbolism, impressionism and fauvism among others.[42][43]

The history of 20th-century art is a narrative of endless possibilities and the search for new standards, each being torn down in succession by the next. Thus the parameters of Impressionism, Expressionism, Fauvism, Cubism, Dadaism, Surrealism, etc. cannot be maintained very much beyond the time of their invention. Increasing global interaction during this time saw an equivalent influence of other cultures into Western art. Thus, Japanese woodblock prints (themselves influenced by Western Renaissance draftsmanship) had an immense influence on impressionism and subsequent development. Later, African sculptures were taken up by Picasso and to some extent by Matisse. Similarly, in the 19th and 20th centuries the West has had huge impacts on Eastern art with originally western ideas like Communism and Post-Modernism exerting a powerful influence.[44]

Modernism, the idealistic search for truth, gave way in the latter half of the 20th century to a realization of its unattainability. Theodor W. Adorno said in 1970, "It is now taken for granted that nothing which concerns art can be taken for granted any more: neither art itself, nor art in relationship to the whole, nor even the right of art to exist."[45] Relativism was accepted as an unavoidable truth, which led to the period of contemporary art and postmodern criticism, where cultures of the world and of history are seen as changing forms, which can be appreciated and drawn from only with skepticism and irony. Furthermore, the separation of cultures is increasingly blurred and some argue it is now more appropriate to think in terms of a global culture, rather than of regional ones.[46]

In The Origin of the Work of Art, Martin Heidegger, a German philosopher and a seminal thinker, describes the essence of art in terms of the concepts of being and truth. He argues that art is not only a way of expressing the element of truth in a culture, but the means of creating it and providing a springboard from which "that which is" can be revealed. Works of art are not merely representations of the way things are, but actually produce a community's shared understanding. Each time a new artwork is added to any culture, the meaning of what it is to exist is inherently changed.

Historically, art and artistic skills and ideas have often been spread through trade. An example of this is the Silk Road, where Hellenistic, Iranian, Indian and Chinese influences could mix. Greco Buddhist art is one of the most vivid examples of this interaction. The meeting of different cultures and worldviews also influenced artistic creation. An example of this is the multicultural port metropolis of Trieste at the beginning of the 20th century, where James Joyce met writers from Central Europe and the artistic development of New York City as a cultural melting pot.[47][48][49]

Forms, genres, media, and styles

The creative arts are often divided into more specific categories, typically along perceptually distinguishable categories such as media, genre, styles, and form.[50] Art form refers to the elements of art that are independent of its interpretation or significance. It covers the methods adopted by the artist and the physical composition of the artwork, primarily non-semantic aspects of the work (i.e., figurae),[51] such as color, contour, dimension, medium, melody, space, texture, and value. Form may also include visual design principles, such as arrangement, balance, contrast, emphasis, harmony, proportion, proximity, and rhythm.[52]

In general there are three schools of philosophy regarding art, focusing respectively on form, content, and context.[52] Extreme Formalism is the view that all aesthetic properties of art are formal (that is, part of the art form). Philosophers almost universally reject this view and hold that the properties and aesthetics of art extend beyond materials, techniques, and form.[53] Unfortunately, there is little consensus on terminology for these informal properties. Some authors refer to subject matter and content—i.e., denotations and connotations—while others prefer terms like meaning and significance.[52]

Extreme Intentionalism holds that authorial intent plays a decisive role in the meaning of a work of art, conveying the content or essential main idea, while all other interpretations can be discarded.[54] It defines the subject as the persons or idea represented,[55] and the content as the artist's experience of that subject.[56] For example, the composition of Napoleon I on his Imperial Throne is partly borrowed from the Statue of Zeus at Olympia. As evidenced by the title, the subject is Napoleon, and the content is Ingres's representation of Napoleon as "Emperor-God beyond time and space".[52] Similarly to extreme formalism, philosophers typically reject extreme intentionalism, because art may have multiple ambiguous meanings and authorial intent may be unknowable and thus irrelevant. Its restrictive interpretation is "socially unhealthy, philosophically unreal, and politically unwise".[52]

Finally, the developing theory of post-structuralism studies art's significance in a cultural context, such as the ideas, emotions, and reactions prompted by a work.[57] The cultural context often reduces to the artist's techniques and intentions, in which case analysis proceeds along lines similar to formalism and intentionalism. However, in other cases historical and material conditions may predominate, such as religious and philosophical convictions, sociopolitical and economic structures, or even climate and geography. Art criticism continues to grow and develop alongside art.[52]

Skill and craft

Art can connote a sense of trained ability or mastery of a medium. Art can also simply refer to the developed and efficient use of a language to convey meaning with immediacy or depth. Art can be defined as an act of expressing feelings, thoughts, and observations.[58]

There is an understanding that is reached with the material as a result of handling it, which facilitates one's thought processes. A common view is that the epithet art, particular in its elevated sense, requires a certain level of creative expertise by the artist, whether this be a demonstration of technical ability, an originality in stylistic approach, or a combination of these two. Traditionally skill of execution was viewed as a quality inseparable from art and thus necessary for its success; for Leonardo da Vinci, art, neither more nor less than his other endeavors, was a manifestation of skill.[59] Rembrandt's work, now praised for its ephemeral virtues, was most admired by his contemporaries for its virtuosity.[60] At the turn of the 20th century, the adroit performances of John Singer Sargent were alternately admired and viewed with skepticism for their manual fluency,[61] yet at nearly the same time the artist who would become the era's most recognized and peripatetic iconoclast, Pablo Picasso, was completing a traditional academic training at which he excelled.[62][63]

A common contemporary criticism of some modern art occurs along the lines of objecting to the apparent lack of skill or ability required in the production of the artistic object. In conceptual art, Marcel Duchamp's Fountain is among the first examples of pieces wherein the artist used found objects ("ready-made") and exercised no traditionally recognised set of skills.[64] Tracey Emin's My Bed, or Damien Hirst's The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living follow this example and also manipulate the mass media. Emin slept (and engaged in other activities) in her bed before placing the result in a gallery as work of art. Hirst came up with the conceptual design for the artwork but has left most of the eventual creation of many works to employed artisans. Hirst's celebrity is founded entirely on his ability to produce shocking concepts.[65] The actual production in many conceptual and contemporary works of art is a matter of assembly of found objects. However, there are many modernist and contemporary artists who continue to excel in the skills of drawing and painting and in creating hands-on works of art.[66]

Purpose

Art has had a great number of different functions throughout its history, making its purpose difficult to abstract or quantify to any single concept. This does not imply that the purpose of art is "vague", but that it has had many unique, different reasons for being created. Some of these functions of art are provided in the following outline. The different purposes of art may be grouped according to those that are non-motivated, and those that are motivated (Lévi-Strauss).[67]

Non-motivated functions

The non-motivated purposes of art are those that are integral to being human, transcend the individual, or do not fulfill a specific external purpose. In this sense, Art, as creativity, is something humans must do by their very nature (i.e., no other species creates art), and is therefore beyond utility.[67]

- Basic human instinct for harmony, balance, rhythm. Art at this level is not an action or an object, but an internal appreciation of balance and harmony (beauty), and therefore an aspect of being human beyond utility.

Imitation, then, is one instinct of our nature. Next, there is the instinct for 'harmony' and rhythm, meters being manifestly sections of rhythm. Persons, therefore, starting with this natural gift developed by degrees their special aptitudes, till their rude improvisations gave birth to Poetry. – Aristotle[68]

- Experience of the mysterious. Art provides a way to experience one's self in relation to the universe. This experience may often come unmotivated, as one appreciates art, music or poetry.

The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the source of all true art and science. – Albert Einstein[69]

- Expression of the imagination. Art provides a means to express the imagination in non-grammatic ways that are not tied to the formality of spoken or written language. Unlike words, which come in sequences and each of which have a definite meaning, art provides a range of forms, symbols and ideas with meanings that are malleable.

Jupiter's eagle [as an example of art] is not, like logical (aesthetic) attributes of an object, the concept of the sublimity and majesty of creation, but rather something else—something that gives the imagination an incentive to spread its flight over a whole host of kindred representations that provoke more thought than admits of expression in a concept determined by words. They furnish an aesthetic idea, which serves the above rational idea as a substitute for logical presentation, but with the proper function, however, of animating the mind by opening out for it a prospect into a field of kindred representations stretching beyond its ken. – Immanuel Kant[70]

- Ritualistic and symbolic functions. In many cultures, art is used in rituals, performances and dances as a decoration or symbol. While these often have no specific utilitarian (motivated) purpose, anthropologists know that they often serve a purpose at the level of meaning within a particular culture. This meaning is not furnished by any one individual, but is often the result of many generations of change, and of a cosmological relationship within the culture.

Most scholars who deal with rock paintings or objects recovered from prehistoric contexts that cannot be explained in utilitarian terms and are thus categorized as decorative, ritual or symbolic, are aware of the trap posed by the term 'art'. – Silva Tomaskova[71]

Motivated functions

Motivated purposes of art refer to intentional, conscious actions on the part of the artists or creator. These may be to bring about political change, to comment on an aspect of society, to convey a specific emotion or mood, to address personal psychology, to illustrate another discipline, to (with commercial arts) sell a product, or simply as a form of communication.[67][72]

- Communication. Art, at its simplest, is a form of communication. As most forms of communication have an intent or goal directed toward another individual, this is a motivated purpose. Illustrative arts, such as scientific illustration, are a form of art as communication. Maps are another example. However, the content need not be scientific. Emotions, moods and feelings are also communicated through art.

[Art is a set of] artefacts or images with symbolic meanings as a means of communication. – Steve Mithen[73]

- Art as entertainment. Art may seek to bring about a particular emotion or mood, for the purpose of relaxing or entertaining the viewer. This is often the function of the art industries of motion pictures and video games.[74]

- The Avant-Garde. Art for political change. One of the defining functions of early 20th-century art has been to use visual images to bring about political change. Art movements that had this goal—Dadaism, Surrealism, Russian constructivism, and Abstract Expressionism, among others—are collectively referred to as the avant-garde arts.

By contrast, the realistic attitude, inspired by positivism, from Saint Thomas Aquinas to Anatole France, clearly seems to me to be hostile to any intellectual or moral advancement. I loathe it, for it is made up of mediocrity, hate, and dull conceit. It is this attitude which today gives birth to these ridiculous books, these insulting plays. It constantly feeds on and derives strength from the newspapers and stultifies both science and art by assiduously flattering the lowest of tastes; clarity bordering on stupidity, a dog's life. – André Breton (Surrealism)[75]

- Art as a "free zone", removed from the action of the social censure. Unlike theavant-garde movements, which wanted to erase cultural differences in order to produce new universal values, contemporary art has enhanced its tolerance towards cultural differences as well as its critical and liberating functions (social inquiry, activism, subversion, deconstruction, etc.), becoming a more open place for research and experimentation.[76]

- Art for social inquiry, subversion or anarchy. While similar to art for political change, subversive or deconstructivist art may seek to question aspects of society without any specific political goal. In this case, the function of art may be simply to criticize some aspect of society.

Spray-paint graffiti on a wall in Rome

Spray-paint graffiti on a wall in Rome - Art for social causes. Art can be used to raise awareness for a large variety of causes. A number of art activities were aimed at raising awareness of autism,[77][78][79] cancer,[80][81][82] human trafficking,[83][84] and a variety of other topics, such as ocean conservation,[85] human rights in Darfur,[86] murdered and missing Aboriginal women,[87] elder abuse,[88] and pollution.[89] Trashion, using trash to make fashion, practiced by artists such as Marina DeBris is one example of using art to raise awareness about pollution.

- Art for psychological and healing purposes. Art is also used by art therapists, psychotherapists and clinical psychologists as art therapy. The Diagnostic Drawing Series, for example, is used to determine the personality and emotional functioning of a patient. The end product is not the principal goal in this case, but rather a process of healing, through creative acts, is sought. The resultant piece of artwork may also offer insight into the troubles experienced by the subject and may suggest suitable approaches to be used in more conventional forms of psychiatric therapy.[90]

- Art for propaganda, or commercialism. Art is often utilized as a form of propaganda, and thus can be used to subtly influence popular conceptions or mood. In a similar way, art that tries to sell a product also influences mood and emotion. In both cases, the purpose of art here is to subtly manipulate the viewer into a particular emotional or psychological response toward a particular idea or object.[91]

- Art as a fitness indicator. It has been argued that the ability of the human brain by far exceeds what was needed for survival in the ancestral environment. One evolutionary psychology explanation for this is that the human brain and associated traits (such as artistic ability and creativity) are the human equivalent of the peacock's tail. The purpose of the male peacock's extravagant tail has been argued to be to attract females (see also Fisherian runaway and handicap principle). According to this theory superior execution of art was evolutionarily important because it attracted mates.[92]

The functions of art described above are not mutually exclusive, as many of them may overlap. For example, art for the purpose of entertainment may also seek to sell a product, i.e. the movie or video game.

Public access

.jpg.webp)

Since ancient times, much of the finest art has represented a deliberate display of wealth or power, often achieved by using massive scale and expensive materials. Much art has been commissioned by political rulers or religious establishments, with more modest versions only available to the most wealthy in society.[93]

Nevertheless, there have been many periods where art of very high quality was available, in terms of ownership, across large parts of society, above all in cheap media such as pottery, which persists in the ground, and perishable media such as textiles and wood. In many different cultures, the ceramics of indigenous peoples of the Americas are found in such a wide range of graves that they were clearly not restricted to a social elite,[94] though other forms of art may have been. Reproductive methods such as moulds made mass-production easier, and were used to bring high-quality Ancient Roman pottery and Greek Tanagra figurines to a very wide market. Cylinder seals were both artistic and practical, and very widely used by what can be loosely called the middle class in the Ancient Near East.[95] Once coins were widely used, these also became an art form that reached the widest range of society.[96]

Another important innovation came in the 15th century in Europe, when printmaking began with small woodcuts, mostly religious, that were often very small and hand-colored, and affordable even by peasants who glued them to the walls of their homes. Printed books were initially very expensive, but fell steadily in price until by the 19th century even the poorest could afford some with printed illustrations.[97] Popular prints of many different sorts have decorated homes and other places for centuries.[98]

In 1661, the city of Basel, in Switzerland, opened the first public museum of art in the world, the Kunstmuseum Basel. Today, its collection is distinguished by an impressively wide historic span, from the early 15th century up to the immediate present. Its various areas of emphasis give it international standing as one of the most significant museums of its kind. These encompass: paintings and drawings by artists active in the Upper Rhine region between 1400 and 1600, and on the art of the 19th to 21st centuries.[99]

Public buildings and monuments, secular and religious, by their nature normally address the whole of society, and visitors as viewers, and display to the general public has long been an important factor in their design. Egyptian temples are typical in that the most largest and most lavish decoration was placed on the parts that could be seen by the general public, rather than the areas seen only by the priests.[100] Many areas of royal palaces, castles and the houses of the social elite were often generally accessible, and large parts of the art collections of such people could often be seen, either by anybody, or by those able to pay a small price, or those wearing the correct clothes, regardless of who they were, as at the Palace of Versailles, where the appropriate extra accessories (silver shoe buckles and a sword) could be hired from shops outside.[101]

Special arrangements were made to allow the public to see many royal or private collections placed in galleries, as with the Orleans Collection mostly housed in a wing of the Palais Royal in Paris, which could be visited for most of the 18th century.[102] In Italy the art tourism of the Grand Tour became a major industry from the Renaissance onwards, and governments and cities made efforts to make their key works accessible. The British Royal Collection remains distinct, but large donations such as the Old Royal Library were made from it to the British Museum, established in 1753. The Uffizi in Florence opened entirely as a gallery in 1765, though this function had been gradually taking the building over from the original civil servants' offices for a long time before.[103] The building now occupied by the Prado in Madrid was built before the French Revolution for the public display of parts of the royal art collection, and similar royal galleries open to the public existed in Vienna, Munich and other capitals. The opening of the Musée du Louvre during the French Revolution (in 1793) as a public museum for much of the former French royal collection certainly marked an important stage in the development of public access to art, transferring ownership to a republican state, but was a continuation of trends already well established.[104]

Most modern public museums and art education programs for children in schools can be traced back to this impulse to have art available to everyone. However, museums do not only provide availability to art, but do also influence the way art is being perceived by the audience, as studies found.[105] Thus, the museum itself is not only a blunt stage for the presentation of art, but plays an active and vital role in the overall perception of art in modern society.

Museums in the United States tend to be gifts from the very rich to the masses. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, for example, was created by John Taylor Johnston, a railroad executive whose personal art collection seeded the museum.) But despite all this, at least one of the important functions of art in the 21st century remains as a marker of wealth and social status.[106]

There have been attempts by artists to create art that can not be bought by the wealthy as a status object. One of the prime original motivators of much of the art of the late 1960s and 1970s was to create art that could not be bought and sold. It is "necessary to present something more than mere objects"[107] said the major post war German artist Joseph Beuys. This time period saw the rise of such things as performance art, video art, and conceptual art. The idea was that if the artwork was a performance that would leave nothing behind, or was simply an idea, it could not be bought and sold. "Democratic precepts revolving around the idea that a work of art is a commodity impelled the aesthetic innovation which germinated in the mid-1960s and was reaped throughout the 1970s. Artists broadly identified under the heading of Conceptual art ... substituting performance and publishing activities for engagement with both the material and materialistic concerns of painted or sculptural form ... [have] endeavored to undermine the art object qua object."[108]

In the decades since, these ideas have been somewhat lost as the art market has learned to sell limited edition DVDs of video works,[109] invitations to exclusive performance art pieces, and the objects left over from conceptual pieces. Many of these performances create works that are only understood by the elite who have been educated as to why an idea or video or piece of apparent garbage may be considered art. The marker of status becomes understanding the work instead of necessarily owning it, and the artwork remains an upper-class activity. "With the widespread use of DVD recording technology in the early 2000s, artists, and the gallery system that derives its profits from the sale of artworks, gained an important means of controlling the sale of video and computer artworks in limited editions to collectors."[110]

Controversies

.jpg.webp)

Art has long been controversial, that is to say disliked by some viewers, for a wide variety of reasons, though most pre-modern controversies are dimly recorded, or completely lost to a modern view. Iconoclasm is the destruction of art that is disliked for a variety of reasons, including religious ones. Aniconism is a general dislike of either all figurative images, or often just religious ones, and has been a thread in many major religions. It has been a crucial factor in the history of Islamic art, where depictions of Muhammad remain especially controversial. Much art has been disliked purely because it depicted or otherwise stood for unpopular rulers, parties or other groups. Artistic conventions have often been conservative and taken very seriously by art critics, though often much less so by a wider public. The iconographic content of art could cause controversy, as with late medieval depictions of the new motif of the Swoon of the Virgin in scenes of the Crucifixion of Jesus. The Last Judgment by Michelangelo was controversial for various reasons, including breaches of decorum through nudity and the Apollo-like pose of Christ.[111][112]

The content of much formal art through history was dictated by the patron or commissioner rather than just the artist, but with the advent of Romanticism, and economic changes in the production of art, the artists' vision became the usual determinant of the content of his art, increasing the incidence of controversies, though often reducing their significance. Strong incentives for perceived originality and publicity also encouraged artists to court controversy. Théodore Géricault's Raft of the Medusa (c. 1820), was in part a political commentary on a recent event. Édouard Manet's Le Déjeuner sur l'Herbe (1863), was considered scandalous not because of the nude woman, but because she is seated next to men fully dressed in the clothing of the time, rather than in robes of the antique world.[113][114] John Singer Sargent's Madame Pierre Gautreau (Madam X) (1884), caused a controversy over the reddish pink used to color the woman's ear lobe, considered far too suggestive and supposedly ruining the high-society model's reputation.[115][116] The gradual abandonment of naturalism and the depiction of realistic representations of the visual appearance of subjects in the 19th and 20th centuries led to a rolling controversy lasting for over a century.

In the 20th century, Pablo Picasso's Guernica (1937) used arresting cubist techniques and stark monochromatic oils, to depict the harrowing consequences of a contemporary bombing of a small, ancient Basque town. Leon Golub's Interrogation III (1981), depicts a female nude, hooded detainee strapped to a chair, her legs open to reveal her sexual organs, surrounded by two tormentors dressed in everyday clothing. Andres Serrano's Piss Christ (1989) is a photograph of a crucifix, sacred to the Christian religion and representing Christ's sacrifice and final suffering, submerged in a glass of the artist's own urine. The resulting uproar led to comments in the United States Senate about public funding of the arts.[117][118]

Theory

Before Modernism, aesthetics in Western art was greatly concerned with achieving the appropriate balance between different aspects of realism or truth to nature and the ideal; ideas as to what the appropriate balance is have shifted to and fro over the centuries. This concern is largely absent in other traditions of art. The aesthetic theorist John Ruskin, who championed what he saw as the naturalism of J. M. W. Turner, saw art's role as the communication by artifice of an essential truth that could only be found in nature.[119]

The definition and evaluation of art has become especially problematic since the 20th century. Richard Wollheim distinguishes three approaches to assessing the aesthetic value of art: the Realist, whereby aesthetic quality is an absolute value independent of any human view; the Objectivist, whereby it is also an absolute value, but is dependent on general human experience; and the Relativist position, whereby it is not an absolute value, but depends on, and varies with, the human experience of different humans.[120]

Arrival of Modernism

The arrival of Modernism in the late 19th century lead to a radical break in the conception of the function of art,[121] and then again in the late 20th century with the advent of postmodernism. Clement Greenberg's 1960 article "Modernist Painting" defines modern art as "the use of characteristic methods of a discipline to criticize the discipline itself".[122] Greenberg originally applied this idea to the Abstract Expressionist movement and used it as a way to understand and justify flat (non-illusionistic) abstract painting:

Realistic, naturalistic art had dissembled the medium, using art to conceal art; modernism used art to call attention to art. The limitations that constitute the medium of painting—the flat surface, the shape of the support, the properties of the pigment—were treated by the Old Masters as negative factors that could be acknowledged only implicitly or indirectly. Under Modernism these same limitations came to be regarded as positive factors, and were acknowledged openly.[122]

After Greenberg, several important art theorists emerged, such as Michael Fried, T. J. Clark, Rosalind Krauss, Linda Nochlin and Griselda Pollock among others. Though only originally intended as a way of understanding a specific set of artists, Greenberg's definition of modern art is important to many of the ideas of art within the various art movements of the 20th century and early 21st century.[123][124]

Pop artists like Andy Warhol became both noteworthy and influential through work including and possibly critiquing popular culture, as well as the art world. Artists of the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s expanded this technique of self-criticism beyond high art to all cultural image-making, including fashion images, comics, billboards and pornography.[125][126]

Duchamp once proposed that art is any activity of any kind-everything. However, the way that only certain activities are classified today as art is a social construction.[127] There is evidence that there may be an element of truth to this. In The Invention of Art: A Cultural History, Larry Shiner examines the construction of the modern system of the arts, i.e. fine art. He finds evidence that the older system of the arts before our modern system (fine art) held art to be any skilled human activity; for example, Ancient Greek society did not possess the term art, but techne. Techne can be understood neither as art or craft, the reason being that the distinctions of art and craft are historical products that came later on in human history. Techne included painting, sculpting and music, but also cooking, medicine, horsemanship, geometry, carpentry, prophecy, and farming, etc.[128]

New Criticism and the "intentional fallacy"

Following Duchamp during the first half of the 20th century, a significant shift to general aesthetic theory took place which attempted to apply aesthetic theory between various forms of art, including the literary arts and the visual arts, to each other. This resulted in the rise of the New Criticism school and debate concerning the intentional fallacy. At issue was the question of whether the aesthetic intentions of the artist in creating the work of art, whatever its specific form, should be associated with the criticism and evaluation of the final product of the work of art, or, if the work of art should be evaluated on its own merits independent of the intentions of the artist.[129][130]

In 1946, William K. Wimsatt and Monroe Beardsley published a classic and controversial New Critical essay entitled "The Intentional Fallacy", in which they argued strongly against the relevance of an author's intention, or "intended meaning" in the analysis of a literary work. For Wimsatt and Beardsley, the words on the page were all that mattered; importation of meanings from outside the text was considered irrelevant, and potentially distracting.[131][132]

In another essay, "The Affective Fallacy", which served as a kind of sister essay to "The Intentional Fallacy" Wimsatt and Beardsley also discounted the reader's personal/emotional reaction to a literary work as a valid means of analyzing a text. This fallacy would later be repudiated by theorists from the reader-response school of literary theory. Ironically, one of the leading theorists from this school, Stanley Fish, was himself trained by New Critics. Fish criticizes Wimsatt and Beardsley in his 1970 essay "Literature in the Reader".[133][134]

As summarized by Berys Gaut and Paisley Livingston in their essay "The Creation of Art": "Structuralist and post-structuralists theorists and critics were sharply critical of many aspects of New Criticism, beginning with the emphasis on aesthetic appreciation and the so-called autonomy of art, but they reiterated the attack on biographical criticisms' assumption that the artist's activities and experience were a privileged critical topic."[135] These authors contend that: "Anti-intentionalists, such as formalists, hold that the intentions involved in the making of art are irrelevant or peripheral to correctly interpreting art. So details of the act of creating a work, though possibly of interest in themselves, have no bearing on the correct interpretation of the work."[136]

Gaut and Livingston define the intentionalists as distinct from formalists stating that: "Intentionalists, unlike formalists, hold that reference to intentions is essential in fixing the correct interpretation of works." They quote Richard Wollheim as stating that, "The task of criticism is the reconstruction of the creative process, where the creative process must in turn be thought of as something not stopping short of, but terminating on, the work of art itself."[136]

"Linguistic turn" and its debate

The end of the 20th century fostered an extensive debate known as the linguistic turn controversy, or the "innocent eye debate" in the philosophy of art. This debate discussed the encounter of the work of art as being determined by the relative extent to which the conceptual encounter with the work of art dominates over the perceptual encounter with the work of art.[137]

Decisive for the linguistic turn debate in art history and the humanities were the works of yet another tradition, namely the structuralism of Ferdinand de Saussure and the ensuing movement of poststructuralism. In 1981, the artist Mark Tansey created a work of art titled The Innocent Eye as a criticism of the prevailing climate of disagreement in the philosophy of art during the closing decades of the 20th century. Influential theorists include Judith Butler, Luce Irigaray, Julia Kristeva, Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida. The power of language, more specifically of certain rhetorical tropes, in art history and historical discourse was explored by Hayden White. The fact that language is not a transparent medium of thought had been stressed by a very different form of philosophy of language which originated in the works of Johann Georg Hamann and Wilhelm von Humboldt.[138] Ernst Gombrich and Nelson Goodman in his book Languages of Art: An Approach to a Theory of Symbols came to hold that the conceptual encounter with the work of art predominated exclusively over the perceptual and visual encounter with the work of art during the 1960s and 1970s.[139] He was challenged on the basis of research done by the Nobel prize winning psychologist Roger Sperry who maintained that the human visual encounter was not limited to concepts represented in language alone (the linguistic turn) and that other forms of psychological representations of the work of art were equally defensible and demonstrable. Sperry's view eventually prevailed by the end of the 20th century with aesthetic philosophers such as Nick Zangwill strongly defending a return to moderate aesthetic formalism among other alternatives.[140]

Classification disputes

Disputes as to whether or not to classify something as a work of art are referred to as classificatory disputes about art. Classificatory disputes in the 20th century have included cubist and impressionist paintings, Duchamp's Fountain, the movies, J. S. G. Boggs' superlative imitations of banknotes, conceptual art, and video games.[142] Philosopher David Novitz has argued that disagreement about the definition of art are rarely the heart of the problem. Rather, "the passionate concerns and interests that humans vest in their social life" are "so much a part of all classificatory disputes about art."[143] According to Novitz, classificatory disputes are more often disputes about societal values and where society is trying to go than they are about theory proper. For example, when the Daily Mail criticized Hirst's and Emin's work by arguing "For 1,000 years art has been one of our great civilising forces. Today, pickled sheep and soiled beds threaten to make barbarians of us all" they are not advancing a definition or theory about art, but questioning the value of Hirst's and Emin's work.[144] In 1998, Arthur Danto, suggested a thought experiment showing that "the status of an artifact as work of art results from the ideas a culture applies to it, rather than its inherent physical or perceptible qualities. Cultural interpretation (an art theory of some kind) is therefore constitutive of an object's arthood."[145][146]

Anti-art is a label for art that intentionally challenges the established parameters and values of art;[147] it is a term associated with Dadaism and attributed to Marcel Duchamp just before World War I,[147] when he was making art from found objects.[147] One of these, Fountain (1917), an ordinary urinal, has achieved considerable prominence and influence on art.[147] Anti-art is a feature of work by Situationist International,[148] the lo-fi Mail art movement, and the Young British Artists,[147] though it is a form still rejected by the Stuckists,[147] who describe themselves as anti-anti-art.[149][150]

Architecture is often included as one of the visual arts; however, like the decorative arts, or advertising, it involves the creation of objects where the practical considerations of use are essential in a way that they usually are not in a painting, for example.[151]

Value judgment

Somewhat in relation to the above, the word art is also used to apply judgments of value, as in such expressions as "that meal was a work of art" (the cook is an artist),[152] or "the art of deception" (the highly attained level of skill of the deceiver is praised). It is this use of the word as a measure of high quality and high value that gives the term its flavor of subjectivity. Making judgments of value requires a basis for criticism. At the simplest level, a way to determine whether the impact of the object on the senses meets the criteria to be considered art is whether it is perceived to be attractive or repulsive. Though perception is always colored by experience, and is necessarily subjective, it is commonly understood that what is not somehow aesthetically satisfying cannot be art. However, "good" art is not always or even regularly aesthetically appealing to a majority of viewers. In other words, an artist's prime motivation need not be the pursuit of the aesthetic. Also, art often depicts terrible images made for social, moral, or thought-provoking reasons. For example, Francisco Goya's painting depicting the Spanish shootings of 3 May 1808 is a graphic depiction of a firing squad executing several pleading civilians. Yet at the same time, the horrific imagery demonstrates Goya's keen artistic ability in composition and execution and produces fitting social and political outrage. Thus, the debate continues as to what mode of aesthetic satisfaction, if any, is required to define 'art'.[153][154]

The assumption of new values or the rebellion against accepted notions of what is aesthetically superior need not occur concurrently with a complete abandonment of the pursuit of what is aesthetically appealing. Indeed, the reverse is often true, that the revision of what is popularly conceived of as being aesthetically appealing allows for a re-invigoration of aesthetic sensibility, and a new appreciation for the standards of art itself. Countless schools have proposed their own ways to define quality, yet they all seem to agree in at least one point: once their aesthetic choices are accepted, the value of the work of art is determined by its capacity to transcend the limits of its chosen medium to strike some universal chord by the rarity of the skill of the artist or in its accurate reflection in what is termed the zeitgeist. Art is often intended to appeal to and connect with human emotion. It can arouse aesthetic or moral feelings, and can be understood as a way of communicating these feelings. Artists express something so that their audience is aroused to some extent, but they do not have to do so consciously. Art may be considered an exploration of the human condition; that is, what it is to be human.[155] By extension, it has been argued by Emily L. Spratt that the development of artificial intelligence, especially in regard to its uses with images, necessitates a re-evaluation of aesthetic theory in art history today and a reconsideration of the limits of human creativity.[156][157]

Art and law

An essential legal issue are art forgeries, plagiarism, replicas and works that are strongly based on other works of art.

The trade in works of art or the export from a country may be subject to legal regulations. Internationally there are also extensive efforts to protect the works of art created. The UN, UNESCO and Blue Shield International try to ensure effective protection at the national level and to intervene directly in the event of armed conflicts or disasters. This can particularly affect museums, archives, art collections and excavation sites. This should also secure the economic basis of a country, especially because works of art are often of tourist importance. The founding president of Blue Shield International, Karl von Habsburg, explained an additional connection between the destruction of cultural property and the cause of flight during a mission in Lebanon in April 2019: “Cultural goods are part of the identity of the people who live in a certain place. If you destroy their culture, you also destroy their identity. Many people are uprooted, often no longer have any prospects and as a result flee from their homeland.”[158][159][160][161][162][163]

See also

- Applied arts

- Art movement

- Artist in residence

- Artistic freedom

- Cultural tourism

- Craftivism

- Formal analysis

- History of art

- List of artistic media

- List of art techniques

- Mathematics and art

- Street art (or "independent public art")

- Outline of the visual arts, a guide to the subject of art presented as a tree structured list of its subtopics.

- Visual impairment in art

Notes

- "Art: definition". Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 1 September 2016. Retrieved 25 December 2015.

- "art". Merriam-Websters Dictionary. Archived from the original on 30 August 2019. Retrieved 25 December 2015.

- "Conceptual Art | Definition of Conceptual Art by Oxford Dictionary on Lexico.com also meaning of Conceptual Art". Lexico Dictionaries | English. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- Stephen Davies (1991). Definitions of Art. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-9794-0.

- Robert Stecker (1997). Artworks: Definition, Meaning, Value. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-01596-5.

- Noël Carroll, ed. (2000). Theories of Art Today. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-16354-9.

- Vasari, Giorgio (18 December 2007). The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 9780307432391. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- "Art, n. 1". OED Online. December 2011. Oxford University Press. https://www.oed.com Archived 11 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine. (Accessed 26 February 2012.)

- Kennick, W. E. (1979). Art and Philosophy: Readings in Aesthetics. New York (NY): St. Martin's Press. pp. xi–xiii. ISBN 978-0-312-05391-8. OCLC 1064878696.

- "Art". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 11 March 2009. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- Elkins, James (December 1995). "Art History and Images That Are Not Art (with previous bibliography)". The Art Bulletin. 77 (4): 553–571. doi:10.2307/3046136. ISSN 0004-3079. JSTOR 3046136. Archived from the original on 18 August 2021.

Non-Western images are not well described in terms of art, and neither are medieval paintings that were made in the absence of humanist ideas of artistic value

- Gilbert, Kuhn pp. 73–96

- Gilbert, Kuhn pp. 40–72

- Aristotle, Poetics I 1447a

- Aristotle, Poetics III

- Aristotle, Poetics IV

- Languages, Oxford (20 September 2007). Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (6th ed.). Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 119–121. ISBN 978-0-19-920687-2. OCLC 170973920. Archived from the original on 3 March 2022.

- Gilbert, Kuhn pp. 287–326

- David Novitz, The Boundaries of Art, 1992

- Richard Wollheim, Art and its objects, p. 1, 2nd ed., 1980, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-29706-0

- Jerrold Levinson, The Oxford Handbook of Aesthetics, Oxford University Press, 2003, p. 5. ISBN 0-19-927945-4

- Jerrold Levinson, The Oxford Handbook of Aesthetics, Oxford University Press, 2003, p. 16. ISBN 0-19-927945-4

- R.G. Collingwood's view, expressed in The Principles of Art, is considered in Wollheim, op. cit. 1980 pp. 36–43

- Martin Heidegger, "The Origin of the Work of Art", in Poetry, Language, Thought, (Harper Perennial, 2001). See also Maurice Merleau-Ponty, "Cézanne's Doubt" in The Merleau-Ponty Aesthetics Reader, Galen Johnson and Michael Smith (eds), (Northwestern University Press, 1994) and John Russon, Bearing Witness to Epiphany, (State University of New York Press, 2009).

- W. E. Kennick, Art and Philosophy: Readings in Aesthetics. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1979, p. 89. ISBN 0-312-05391-6.

- Shiner 2003. The Invention of Art: A Cultural History. The University of Chicago Press Books. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-226-75342-3

- Gombrich, Ernst. (2005). "Press statement on The Story of Art". The Gombrich Archive. Archived from the original on 6 October 2008.

- "Shell 'Art' Made 300,000 Years Before Humans Evolved". New Scientist. Reed Business Information Ltd. 3 December 2014. Archived from the original on 6 June 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- "130,000-Year-Old Neanderthal 'Eagle Claw Necklace' Found in Croatia". Sci-News.com. 11 March 2015. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- Radford, Tim. ""World's Oldest Jewellery Found in Cave"". 16 April 2004. Archived from the original on 8 February 2008. Retrieved 18 January 2008.. Guardian Unlimited, 16 April 2004. Retrieved on 18 January 2008.

- "African Cave Yields Evidence of a Prehistoric Paint Factory". The New York Times. 13 October 2011. Archived from the original on 1 January 2022.

- Cyranoski, David (8 October 2014). "World's oldest art found in Indonesian cave". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2014.16100. S2CID 189968118. Archived from the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- Gombrich, p.83, pp.75–115 pp.132–141, pp.147–155, p.163, p.627.

- Gombrich, pp. 86–89, pp. 135–141, p. 143, p. 179, p. 185.

- Tom Nichols (1 December 2012). Renaissance Art: A Beginner's Guide. Oneworld Publications. ISBN 978-1-78074-178-9. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- The Genius of Arab Civilization: Source of Renaissance. MIT Press. 1 January 1983. ISBN 9780262081368. Archived from the original on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- Gombrich, pp. 127-128

- Gombrich, pp. 634–635

- William Watson (1995). The Arts of China 900–1620. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09835-8. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- Gombrich, p. 155, p. 530.

- Colin Moore (6 August 2010). Propaganda Prints: A History of Art in the Service of Social and Political Change. A&C Black. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-4081-0591-7. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- Gombrich, pp.394–395, pp.519–527, pp. 573–575.

- "The Age of Enlightenment An Anthology Prepared for the Enlightenment Book Club" (PDF). pp. 1–45. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 May 2018. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- The New York Times Book Review. Vol. 1, 84. The New York Times Company. 1979. p. 30. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- Adorno, Theodor W., Aesthetic Theory, (1970 in German)

- Dr. Sangeeta (2017). Development of Modern Art Criticism in India after Independence: Post Independence Indian Art Criticism. Notion Press. ISBN 978-1-947697-31-7. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- Liu, Xinru "The Silk Road in World History" (New York 2010), pp 21.

- Veronika Eckl "Vom Leben in Cafés und zwischen Buchdeckeln" In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung 17.01.2008; Angelo Ara, Claudio Magris "Triest Eine literarische Hauptstadt Mitteleuropas (Trieste: un’identità di frontiera)" (1987).

- "How did New York City become the centre of the western art world?". 26 September 2016. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- Walton, Kendall L. (1 January 1970). "Categories of Art". The Philosophical Review. 79 (3): 334–67. doi:10.2307/2183933. JSTOR 2183933.

- Monelle, Raymond (3 January 1992). Linguistics and Semiotics in Music. Routledge. p. 202. ISBN 978-3718652099. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- Belton, Dr. Robert J. (1996). "The Elements of Art". Art History: A Preliminary Handbook. Archived from the original on 27 February 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- Xu, Min; Deng, Guifang (2 December 2014). "Against Zangwill's Extreme Formalism About Inorganic Nature" (PDF). Philosophia. 43 (1): 249–57. doi:10.1007/s11406-014-9575-1. S2CID 55901464. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 February 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- Livingston, Paisley (1998). "Intentionalism in Aesthetics". New Literary History. 29 (4): 831–46. doi:10.1353/nlh.1998.0042. S2CID 53618673. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017.

- Munk, Eduard; Beck, Charles; Felton, Cornelius Conway (1844). The Metres of the Greeks and Romans. p. 1. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- Tolstoy, Leo (1899). What is Art?. Crowell. p. 24.

- Emiroğlu, Melahat Küçükarslan; Koş, Fitnat Cimşit (16–20 September 2014). Design Semiotics and Post-Structuralism. 12th World Congress of Semiotics. New Bulgarian University. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- Breskin, Vladimir, ""Triad: Method for studying the core of the semiotic parity of language and art"" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 September 2011., Signs – International Journal of Semiotics 3, pp. 1–28, 2010. ISSN 1902-8822

- The Illustrated London News. Illustrated London News & Sketch Limited. 1872. p. 502. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- Eric Newton; William Neil (1966). 2000 Years of Christian Art. Harper & Row. p. 184. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- Kirk Richards; Stephen Gjertson (2002). For glory and for beauty: practical perspectives on Christianity and the visual arts. American Society of Classical Realism. ISBN 978-0-9636180-4-7. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- Richard Leslie (30 December 2005). Pablo Picasso: A Modern Master. New Line Books. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-59764-094-7. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- Jane Dillenberger; John Handley (17 April 2014). The Religious Art of Pablo Picasso. Univ of California Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-520-27629-1. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- Fred S. Kleiner (2009). Gardner's Art through the Ages: The Western Perspective. Cengage Learning. pp. 24–27. ISBN 978-0-495-57364-7. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- White, Luke (1 January 2013). Damien Hirst's Shark: Nature, Capitalism and the Sublime. Tate. ISBN 9781849763875. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- La Belle Assemblée. Vol. V. J. Bell. 1808. p. 8. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- Giovanni Schiuma (19 May 2011). The Value of Arts for Business. Cambridge University Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-139-49665-0. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- Aristotle. "[Book 10:] The Poetics". Republic. www.authorama.com. Note: Although speaking mostly of poetry here, the Ancient Greeks often speak of the arts collectively. Archived from the original on 8 May 2008. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- Einstein, Albert. "The World as I See It". https://www.aip.org/history/einstein/essay.htm Archived 8 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Immanuel Kant, Critique of Aesthetic Judgement (1790).

- Silvia Tomaskova, Places of Art: Art and Archaeology in Context: (1997)

- Constantine Stephanidis (24 June 2011). HCI International 2011 Posters' Extended Abstracts: International Conference, HCI International 2011, Orlando, FL, USA, July 9–14, 2011, Proceedings. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 529–533. ISBN 978-3-642-22094-4. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- Steve Mithen. The Prehistory of the Mind: The Cognitive Origins of Art, Religion and Science. 1999

- Information Resources Management Association (30 June 2014). Digital Arts and Entertainment: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications. USA: IGI Global. p. 976. ISBN 978-1-4666-6115-8. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- "André Breton, Manifesto of Surrealism (1924)". Archived from the original on 25 May 2020. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- According to Maurizio Bolognini this is not only associated with the postmodern rejection of all canons but with a process of secularization of art, which is finally considered as "a mere (albeit essential) convention, sustained and reproduced by the art system (artists, galleries, critics, collectors), providing a free zone, that is, a more open place for experimentation, removed from the constraints of the practical sphere.": see Maurizio Bolognini (2008). Postdigitale. Rome: Carocci. ISBN 978-88-430-4739-0. Archived from the original on 18 January 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2013., "chap. 3". Archived from the original on 18 January 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2013..

- Trotter, Jeramia (15 February 2011). "RiverKings raising autism awareness with art". WMC tv. Archived from the original on 22 February 2011.

- "Art exhibit aims to raise awareness of autism". Daily News-Miner. 4 April 2012. Archived from the original on 9 October 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- "Anchorage art exhibit to raise awareness about autism" (PDF). Alaska Department of Health and Social Services. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 March 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- Ruhl, Ashleigh (18 February 2013). "Photographer Seeks Subjects To Help Raise Cancer Awareness". Gazettes. Archived from the original on 21 February 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- "Bra art raising awareness for breast cancer". The Palm Beach Post. n.d. Archived from the original on 9 October 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- Flynn, Marella (10 January 2007). "October art walk aims to raise money, awareness for breast cancer". Flagler College Gargoyle. Archived from the original on 20 February 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- "Students get creative in the fight against human trafficking". WDTN Channel 2 News. 26 November 2012. Archived from the original on 30 June 2013.

- "Looking to raise awareness at ArtPrize". WWMT, Newschannel 3. 10 January 2012. Archived from the original on 6 October 2012.

- "SciCafe – Art/Sci Collision: Raising Ocean Conservation Awareness". American Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on 3 July 2013. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- "SMU students raise awareness with 'Art for Darfur'". SMU News Release. 4 March 2008. Archived from the original on 3 April 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- Donnelly, Greg (3 May 2012). "Red dress art project to raise awareness of murdered and missing Aboriginal women". Global News. Archived from the original on 18 May 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- "Raising elder abuse awareness through intergenerational art". Human Resources and Skills Development Canada. Archived from the original on 22 January 2013. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- Mathema, Paavan (16 January 2013). "Trash to treasure: Turning Mt. Everest waste into art". CNN. Archived from the original on 9 October 2019. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- Susan Hogan (2001). Healing Arts: The History of Art Therapy. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85302-799-4. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- Roland Barthes, Mythologies

- Dutton, Denis. 2003. "Aesthetics and Evolutionary Psychology" in The Oxford Handbook for Aesthetics. Oxford University Press.

- Gilbert, Kuhn pp. 161–165

- "Ceramics of the Indigenous Peoples of South America: Studies of Production and Exchange using INAA". core.tdar.org. Archived from the original on 28 May 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Barbara Ann Kipfer (30 April 2000). Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 264. ISBN 978-0-306-46158-3. Archived from the original on 10 May 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Ancient Coins as Works of Art. Museum Haaretz. 1960. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- George Hugo Tucker (2000). Forms of the "medieval" in the "Renaissance": A Multidisciplinary Exploration of a Cultural Continuum. Rookwood Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-886365-20-9. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Antony Griffiths (1996). Prints and Printmaking: An Introduction to the History and Techniques. University of California Press. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-520-20714-1.

- "550 Jahre Universität Basel". Archived from the original on 24 September 2017. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- Győző Vörös (2007). Egyptian Temple Architecture: 100 Years of Hungarian Excavations in Egypt, 1907–2007. American Univ in Cairo Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-963-662-084-4. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Adam Waldie (1839). The Select Circulating Library. A. Waldie. p. 367. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Andrea Meyer; Benedicte Savoy (2014). The Museum Is Open: Towards a Transnational History of Museums 1750–1940. De Gruyter. p. 66. ISBN 978-3-11-029882-6. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Gloria Fossi (1999). The Uffizi: The Official Guide : All of the Works. Giunti Editore. pp. 8–11. ISBN 978-88-09-01487-9. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Berger, Robert W. (1999). Public Access to Art in Paris: A Documentary History from the Middle Ages to 1800. Penn State Press. pp. 281–283. ISBN 978-0-271-04434-7. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Susanne Grüner; Eva Specker & Helmut Leder (2019). "Effects of Context and Genuineness in the Experience of Art". Empirical Studies of the Arts. 37 (2): 138–152. doi:10.1177/0276237418822896. S2CID 150115587. Archived from the original on 24 January 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- Michael Findlay (2012). The Value of Art. Prestel Verlag. ISBN 978-3-641-08342-7. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Sharp, Willoughby (December 1969). "An Interview with Joseph Beuys". ArtForum. 8 (4): 45.

- Rorimer, Anne: New Art in the 60s and 70s Redefining Reality, p. 35. Thames and Hudson, 2001.

- Fineman, Mia (21 March 2007). "YouTube for Artists The best places to find video art online". Slate. Archived from the original on 7 September 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2007.

- Robertson, Jean and Craig McDaniel: Themes of Contemporary Art, Visual Art after 1980, p. 16. Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Maureen McCue (2016). British Romanticism and the Reception of Italian Old Master Art, 1793–1840. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-17148-5. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Angela K. Nickerson (2010). A Journey into Michelangelo's Rome. ReadHowYouWant.com. p. 182. ISBN 978-1-4587-8547-3. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Alvina Ruprecht; Cecilia Taiana (1995). Reordering of Culture: Latin America, the Caribbean and Canada in the Hood. McGill-Queen's Press – MQUP. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-88629-269-0. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- John C. Stout (2018). Objects Observed: The Poetry of Things in Twentieth-Century France and America. University of Toronto Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-4875-0157-0. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Claude J. Summers (2004). The Queer Encyclopedia of the Visual Arts. Cleis Press. ISBN 978-1-57344-191-9. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Narim Bender (2014). John Sargent: 121 Drawings. Osmora Incorporated. ISBN 978-2-7659-0006-1. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Roger Chapman; James Ciment (2015). Culture Wars: An Encyclopedia of Issues, Viewpoints and Voices. Routledge. p. 594. ISBN 978-1-317-47351-0. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Brian Arthur Brown (2008). Noah's Other Son: Bridging the Gap Between the Bible and the Qur'an. A&C Black. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-8264-2996-4. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- "go to nature in all singleness of heart, rejecting nothing and selecting nothing, and scorning nothing, believing all things are right and good, and rejoicing always in the truth". Ruskin, John. Modern Painters, Volume I, 1843. London: Smith, Elder and Co.

- Wollheim 1980, Essay VI. pp. 231–39.

- Griselda Pollock, Differencing the Canon. Routledge, London & New York, 1999. ISBN 0-415-06700-6

- Modern Art and Modernism: A Critical Anthology. ed. Francis Frascina and Charles Harrison, 1982.

- Jonathan P. Harris (2005). Writing Back to Modern Art: After Greenberg, Fried, and Clark. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-32429-8. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- David Kenneth Holt (2001). The Search for Aesthetic Meaning in the Visual Arts: The Need for the Aesthetic Tradition in Contemporary Art Theory and Education. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-89789-773-0. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Gerd Gemünden (1998). Framed Visions: Popular Culture, Americanization, and the Contemporary German and Austrian Imagination. University of Michigan Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-472-08560-6. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- The New Yorker. F-R Publishing Corporation. 2004. p. 84. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Duchamp Two Statements on YouTube

- Maria Burguete; Lui Lam (2011). Arts: A Science Matter. World Scientific. p. 74. ISBN 978-981-4324-93-9. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Patricia Waugh (2006). Literary Theory and Criticism: An Oxford Guide. Oxford University Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-19-929133-5. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Claire Colebrook (1997). New Literary Histories: New Historicism and Contemporary Criticism. Manchester University Press. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-7190-4987-3. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Tiger C. Roholt (2013). Key Terms in Philosophy of Art. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 161. ISBN 978-1-4411-3246-8. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Darren Hudson Hick (2017). Introducing Aesthetics and the Philosophy of Art. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-350-00691-1. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Leitch, Vincent B., et al., eds. The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2001.

- Fish, Stanley (Autumn 1970). "Literature in the Reader: Affective Stylistics". New Literary History. 2 (1): 123–162. doi:10.2307/468593. JSTOR 468593.

- Gaut and Livingston, The Creation of Art, p. 3.

- Gaut and Livingston, p. 6.

- Philosophy for Architecture, Branco Mitrovic, 2012.

- Introduction to Structuralism, Michael Lane, Basic Books University of Michigan, 1970.

- Languages of Art: An Approach to a Theory of Symbols. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1968. 2nd ed. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1976. Based on his 1960–61 John Locke lectures.

- Nick Zangwill, "Feasible Aesthetic Formalism", Nous, December 1999, pp. 610–29.

- Tomkins, Duchamp: A Biography, p. 186.

- Deborah Solomon (14 December 2003). "2003: the 3rd Annual Year in Ideas: Video Game Art". The New York Times Magazine. Archived from the original on 1 April 2017. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- Novitz, David (1996). "Disputes about Art". The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. 54 (2): 153–163. doi:10.2307/431087. ISSN 0021-8529. JSTOR 431087.

- Painter, Colin. Contemporary Art and the Home. Berg Publishers, 2002. p. 12. ISBN 1-85973-661-0

- Dutton, Denis ""Tribal Art"". Archived from the original on 17 May 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2008. in Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, edited by Michael Kelly (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998).

- Danto, Arthur. "Artifact and Art" in Art/Artifact, edited by Susan Vogel. New York, 1988.

- ""Glossary: Anti-art"". Archived from the original on 10 September 2009. Retrieved 23 January 2010., Tate. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- Schneider, Caroline. ""Asger Jorn"". Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 24 January 2010., Artforum, 1 September 2001. Retrieved from encyclopedia.com, 24 January 2010.

- Ferguson, Euan. ""In bed with Tracey, Sarah ... and Ron"". TheGuardian.com. 20 April 2003. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2016., The Observer, 20 April 2003. Retrieved on 2 May 2009.

- ""Stuck on the Turner Prize"". Archived from the original on 21 June 2017. Retrieved 22 January 2010., artnet, 27 October 2000. Retrieved on 2 May 2009.

- Glancey, Jonathan (26 July 1995). "Is advertising art?". The Independent. Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 18 August 2017.