Prophecy

In religion, a prophecy is a message that has been communicated to a person (typically called a prophet) by a supernatural entity. Prophecies are a feature of many cultures and belief systems and usually contain divine will or law, or preternatural knowledge, for example of future events. They can be revealed to the prophet in various ways depending on the religion and the story, such as visions, divination, or direct interaction with divine beings in physical form. Stories of prophetic deeds sometimes receive considerable attention and some have been known to survive for centuries through oral tradition or as religious texts.

Etymology

The English noun "prophecy", in the sense of "function of a prophet" appeared from about 1225, from Old French profecie (12th century), and from prophetia, Greek propheteia "gift of interpreting the will of God", from Greek prophetes (see prophet). The related meaning, "thing spoken or written by a prophet", dates from c. 1300, while the verb "to prophesy" is recorded by 1377.[1]

Definitions

- Maimonides suggested that "prophecy is, in truth and reality, an emanation sent forth by Divine Being through the medium of the Active Intellect, in the first instance to man's rational faculty, and then to his imaginative faculty".[2]

- The views of Maimonides closely relate to the definition by Al-Fârâbî, who developed the theory of prophecy in Islam.[3]

- Much of the activity of Old Testament prophets involved conditional warnings rather than immutable futures.[4] A summary of a standard Old Testament prophetic formula might run: Repent of sin X and turn to righteousness, otherwise consequence Y will occur.

- Saint Paul emphasizes edification, exhortation and comfort in a definition of prophesying.[5]

- The Catholic Encyclopedia defines a Christian conception of prophecy as "understood in its strict sense, it means the foreknowledge of future events, though it may sometimes apply to past events of which there is no memory, and to present hidden things which cannot be known by the natural light of reason".[6]

- According to Western esotericist Rosemary Guiley, clairvoyance has been used as an adjunct to "divination, prophecy, and magic".[7]

- From a skeptical point of view, a Latin maxim exists: "prophecy written after the fact" (vaticinium ex eventu).[8] The Jewish Torah already deals with the topic of the false prophet (Deuteronomy 13:2-6, 18:20-22).[9]

In religion

Baháʼí Faith

In 1863, Bahá'u'lláh, the founder of the Baháʼí Faith, claimed to have been the promised messianic figure of all previous religions, and a Manifestation of God,[10] a type of prophet in the Baháʼí writings that serves as intermediary between the divine and humanity and who speaks with the voice of a god.[11] Bahá'u'lláh claimed that, while being imprisoned in the Siyah-Chal in Iran, he underwent a series of mystical experiences including having a vision of the Maid of Heaven who told him of his divine mission, and the promise of divine assistance;[12] In Baháʼí belief, the Maid of Heaven is a representation of the divine.[13]

Buddhism

The Haedong Kosung-jon (Biographies of High Monks) records that King Beopheung of Silla had desired to promulgate Buddhism as the state religion. However, officials in his court opposed him. In the fourteenth year of his reign, Beopheung's "Grand Secretary", Ichadon, devised a strategy to overcome court opposition. Ichadon schemed with the king, convincing him to make a proclamation granting Buddhism official state sanction using the royal seal. Ichadon told the king to deny having made such a proclamation when the opposing officials received it and demanded an explanation. Instead, Ichadon would confess and accept the punishment of execution, for what would quickly be seen as a forgery. Ichadon prophesied to the king that at his execution a wonderful miracle would convince the opposing court faction of Buddhism's power. Ichadon's scheme went as planned, and the opposing officials took the bait. When Ichadon was executed on the 15th day of the 9th month in 527, his prophecy was fulfilled; the earth shook, the sun was darkened, beautiful flowers rained from the sky, his severed head flew to the sacred Geumgang mountains, and milk instead of blood sprayed 100 feet in the air from his beheaded corpse. The omen was accepted by the opposing court officials as a manifestation of heaven's approval, and Buddhism was made the state religion in 527.[14]

Christianity

According to Walter Brueggemann, the task of prophetic (Christian) ministry is to nurture, nourish and evoke a consciousness and perception alternative to the consciousness and perception of the dominant culture.[15] A recognized form of Christian prophecy is the "prophetic drama" which Frederick Dillistone describes as a "metaphorical conjunction between present situations and future events".[16]

Later Christianity

In his Dialogue with Trypho, Justin Martyr argued that prophets were no longer among Israel but were in the Church.[17] The Shepherd of Hermas, written around the mid-2nd century, describes the way prophecy was being used within the church of that time. Irenaeus confirms the existence of such spiritual gifts in his Against Heresies. Although some modern commentators claim that Montanus was rejected because he claimed to be a prophet, a careful examination of history shows that the gift of prophecy was still acknowledged during the time of Montanus, and that he was controversial because of the manner in which he prophesied and the doctrines he propagated.[18]

Prophecy and other spiritual gifts were somewhat rarely acknowledged throughout church history and there are few examples of the prophetic and certain other gifts until the Scottish Covenanters like Prophet Peden and George Wishart. From 1904 to 1906, the Azusa Street Revival occurred in Los Angeles, California and is sometimes considered the birthplace of Pentecostalism. This revival is well known for the "speaking in tongues" that occurred there. Some participants of the Azusa Street Revival are claimed to have prophesied. Pentecostals believe prophecy and certain other gifts are once again being given to Christians. The Charismatic Movement also accepts spiritual gifts like speaking in tongues and prophecy.

Since 1972, the neo-Pentecostal Church of God Ministry of Jesus Christ International has expressed a belief in prophecy. The church claims this gift is manifested by one person (the prophesier) laying their hands on another person, who receives an individual message said by the prophesier. Prophesiers are believed to be used by the Holy Ghost as instruments through whom their God expresses his promises, advice and commandments. The church claims people receive messages about their future, in the form of promises given by their God and expected to be fulfilled by divine action.[19]

Apostolic-Prophetic Movement

In the Apostolic-Prophetic Movement, a prophesy is simply a word delivered under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit that accurately communicates God's "thoughts and intention".[20]

The Apostolic Council of Prophetic Elders was a council of prophetic elders co-convened by C. Peter Wagner and Cindy Jacobs that included: Beth Alves, Jim Gool, Chuck Pierce, Mike and Cindy Jacobs, Bart Pierces, John and Paula Sanford, Dutch Sheets, Tommy Tenny, Heckor Torres, Barbara Wentroble, Mike Bickle, Paul Cain, Emanuele Cannistraci, Bill Hamon, Kingsley Fletcher, Ernest Gentile, Jim Laffoon, James Ryle, and Gwen Shaw.[21]

Latter Day Saint movement

The Latter Day Saint movement maintains that its first prophet, Joseph Smith, was visited by God and Jesus Christ in 1820. The Latter Day Saints further claims that God communicated directly with Joseph Smith on many subsequent occasions, and that following the death of Joseph Smith God has continued to speak through subsequent prophets. Joseph Smith claims to have been led by an angel to a large hill in upstate New York, where he was shown an ancient manuscript engraved on plates of gold metal. Joseph Smith claimed to have translated this manuscript into modern English under divine inspiration by the gift and power of God, and the publication of this translation are known as the Book of Mormon.

Following Smith's murder, there was a succession crisis that resulted in a great schism. The majority of Latter-day Saints believing Brigham Young to be the next prophet and following him out to Utah, while a minority returned to Missouri with Emma Smith, believing Joseph Smith Junior's son, Joseph Smith III, to be the next legitimate prophet (forming the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, now the Community of Christ). Since even before the death of Joseph Smith in 1844, there have been numerous separatist Latter Day Saint sects that have splintered from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. To this day, there are an unknown number of organizations within the Latter Day Saint movement, each with their own proposed prophet.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) is the largest Latter Day Saint body. The current Prophet/President of the LDS Church is Russell M. Nelson. The church has, since Joseph Smith's death on June 27, 1844, held a belief that the president of their church is also a literal prophet of God. The church also maintains that further revelations claimed to have been given through Joseph Smith are published in the Doctrine and Covenants, one of the Standard Works. Additional revelations and prophecies outside the Standard Works, such as Joseph Smith's "White Horse Prophecy", concerning a great and final war in the United States before the Second Coming of Jesus Christ, can be found in other church published works.

Islam

The Arabic term for prophecy nubū'ah (Arabic: نُبُوْءَة) stems from the term for prophets, nabī (Arabic: نَبِي; pl. anbiyāʼ from nabā "tidings, announcement") who are lawbringers that Muslims believe were sent by God to every person, bringing God's message in a language they can understand.[22][23] But there is also the term rasūl (Arabic: رسول "messenger, apostle") to classify those who bring a divine revelation (Arabic: رسالة risālah "message") via an angel.[22][24] Knowledge of the Islamic prophets is one of the six articles of the Islamic faith,[25] and specifically mentioned in the Quran.[26] Along with Muhammad, many of the prophets in Judaism (such as Noah, Abraham, Moses, Aaron, Elijah, etc.) and prophets of Christianity (Adam, Zechariah the priest, John the Baptist, Jesus Christ) are mentioned by name in the Quran.[22]

In the sense of predicting events, the Quran contains verses believed to have predicted many events years before they happened and that such prophecies are proof of the divine origin of the Qur'an. The Qur'an itself states "For every announcement there is a term, and ye will come to know." [Quran 6:67] Muslims also recognize the validity of some prophecies in other sacred texts like in the Bible; however, they believe that, unlike the Qur'an, some parts of the Bible have been corrupted over the years, and as a result, not all of the prophecies and verses in the Bible are accurate.[27]

Judaism

The Hebrew term for prophet, Navi (נבוא), literally means "spokesperson"; he speaks to the people as a mouthpiece of their God, and to their god on behalf of the people. "The name prophet, from the Greek meaning "forespeaker" (πρὸ being used in the original local sense), is an equivalent of the Hebrew Navi, which signifies properly a delegate or mouthpiece of another."[28]

According to Judaism, authentic Nevuah (נבואה, "Prophecy") got withdrawn from the world after the destruction of the first Jerusalem Temple.[28] Malachi is acknowledged to have been the last authentic prophet if one accepts the opinion that Nechemyah died in Babylon before 9th Tevet 3448 (313 BCE).[29]

The Torah contains laws concerning the false prophet (Deuteronomy 13:2-6, 18:20-22). Prophets in Islam like Lot, for example, are false prophets according to Jewish standards.

In the Torah, prophecy often consisted of a conditioned warning by their God of the consequences should the society, specific communities, or their leaders not adhere to Torah's instructions in the time contemporary with the prophet's life. Prophecies sometimes included conditioned promises of blessing for obeying their god, and returning to behaviors and laws as written in the Torah. Conditioned warning prophecies feature in all Jewish works of the Tanakh.

Notably Maimonides, philosophically suggested there once were many levels of prophecy, from the highest such as those experienced by Moses, to the lowest where the individuals were able to apprehend the Divine Will, but not respond or even describe this experience to others, citing in example, Shem, Eber and most notably, Noah, who, in biblical narrative, does not issue prophetic declarations.[30]

Maimonides, in his philosophical work The Guide for the Perplexed, outlines twelve modes of prophecy[31] from lesser to greater degree of clarity:

- Inspired actions

- Inspired words

- Allegorical dream revelations

- Auditory dream revelations

- Audiovisual dream revelations/human speaker

- Audiovisual dream revelations/angelic speaker

- Audiovisual dream revelations/Divine speaker

- Allegorical waking vision

- Auditory waking revelation

- Audiovisual waking revelation/human speaker

- Audiovisual waking revelation/angelic speaker

- Audiovisual waking revelation/Divine speaker (that refers implicitly to Moses)

The Tanakh contains prophecies from various Hebrew prophets (55 in total) who communicated messages from God to the nation of Israel, and later the population of Judea and elsewhere. Experience of prophecy in the Torah and the rest of Tanakh was not restricted to Jews. Nor was the prophetic experience restricted to the Hebrew language.

Native American prophecy

There exists a problem in verifying most Native American prophecy, in that they remain primarily an oral tradition, and thus there is no way to cite references of where writings have been committed to paper. In their system, the best reference is an Elder, who acts as a repository of the accumulated wisdom of their tradition.

In another type of example, it is recorded that there are three Dogrib prophets who had claimed to have been divinely inspired to bring the message of Christianity's God to their people.[32] This prophecy among the Dogrib involves elements such as dances and trance-like states.[33]

China

In ancient Chinese, prophetic texts are known as Chen (谶). The most famous Chinese prophecy is the Tui bei tu (推背圖).

Nostradamus

Esoteric prophecy has been claimed for, but not by, Michel de Nostredame, popularly referred to as Nostradamus, who claimed to be a converted Christian. It is known that he suffered several tragedies in his life, and was persecuted to some degree for his cryptic esoteric writings about the future, reportedly derived through a use of a crystal ball. Nostradamus was a French apothecary and reputed seer who published collections of foreknowledge of future events. He is best known for his book Les Propheties ("The Prophecies"), the first edition of which appeared in 1555. Since Les Propheties was published, Nostradamus has attracted an esoteric following that, along with the popularistic press, credits him with foreseeing world events. His esoteric cryptic foreseeings have in some cases been assimilated to the results of applying the alleged Bible code, as well as to other purported pseudo-prophetic works.

Most reliable academic sources maintain that the associations made between world events and Nostradamus's quatrains are largely the result of misinterpretations or mistranslations (sometimes deliberate) or else are so tenuous as to render them useless as evidence of any genuine predictive power. Moreover, none of the sources listed offers any evidence that anyone has ever interpreted any of Nostradamus's pseudo-prophetic works specifically enough to allow a clear identification of any event in advance.[34]

Explanations

According to skeptics, many apparently fulfilled prophecies can be explained as coincidences, possibly aided by the prophecy's own vagueness, and others may have been invented after the fact to match the circumstances of a past event (an act termed "postdiction").[35][36][37]

Bill Whitcomb in The Magician's Companion observes,

One point to remember is that the probability of an event changes as soon as a prophecy (or divination) exists. . . . The accuracy or outcome of any prophecy is altered by the desires and attachments of the seer and those who hear the prophecy.[38]

Many prophets make a large number of prophecies. This makes the chances of at least one prophecy being correct much higher by sheer weight of numbers.[39]

Psychology

The phenomenon of prophecy is not well understood in psychology research literature. Psychiatrist and neurologist Arthur Deikman describes the phenomenon as an "intuitive knowing, a type of perception that bypasses the usual sensory channels and rational intellect."[40]

"(P)rophecy can be likened to a bridge between the individual 'mystical self' and the communal 'mystical body'," writes religious sociologist Margaret Poloma.[41] Prophecy seems to involve "the free association that occurred through the workings of the right brain."[42]

Psychologist Julian Jaynes proposed that this is a temporary accessing of the bicameral mind; that is, a temporary separating of functions, such that the authoritarian part of the mind seems to literally be speaking to the person as if a separate (and external) voice. Jaynes posits that the gods heard as voices in the head were and are organizations of the central nervous system. God speaking through man, according to Jaynes, is a more recent vestige of God speaking to man; the product of a more integrated higher self. When the bicameral mind speaks, there is no introspection. In earlier times, posits Jaynes, there was additionally a visual component, now lost.[43]

Child development and consciousness author Joseph Chilton Pearce remarked that revelation typically appears in symbolic form and "in a single flash of insight."[44] He used the metaphor of lightning striking and suggests that the revelation is "a result of a buildup of resonant potential."[45] Pearce compared it to the earth asking a question and the sky answering it. Focus, he said, feeds into "a unified field of like resonance (and becomes) capable of attracting and receiving the field's answer when it does form."[46]

Some cite aspects of cognitive psychology such as pattern forming and attention to the formation of prophecy in modern-day society as well as the declining influence of religion in daily life.[47]

Poetry and prophecy

For the ancient Greeks, prediction, prophesy, and poetry were often intertwined.[48] Prophecies were given in verse, and a word for poet in Latin is “vates” or prophet.[48] Both poets and oracles claimed to be inspired by forces outside themselves. In ancient China, divination is regarded as the oldest form of occult inquiry and was often expressed in verse.[49] In contemporary Western cultures, theological revelation and poetry are typically seen as distinct and often even as opposed to each other. Yet the two still are often understood together as symbiotic in their origins, aims, and purposes.[50]

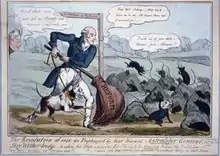

Middle English poems of a political nature are linked with Latin and vernacular prophecies. Prophecies in this sense are predictions concerning kingdoms or peoples; and these predictions are often eschatological or apocalyptic.[51] The prophetic tradition in English derives in from Geoffrey of Monmouth's History of the Kings of Britain (1136), otherwise called "Prophecies of Merlin;" this work is prelude to numerous books devoted to King Arthur. In 18th century England, prophecy as poetry is revived by William Blake[52] who wrote: America: A Prophecy (1783) and Europe: A Prophecy (1794).[51]

Contemporary American poetry is also rich in lyrics about prophesy, including poems entitled Prophecy by Dana Gioia[53] and Eileen Myles. In 1962, Robert Frost published "The Prophets Really Prophesy as Mystics the Commentators Merely by Statistics".[54] Other modern poets who write on prophets or prophecy include Carl Dennis, Richard Wilbur,[55] and Derek Walcott.[56]

See also

- Divination

- False prophets

- Oracle

- Revelation

- Self-fulfilling prophecy

- Vaticinium ex eventu

References

- "Prophecy" in the Online Etymology Dictionary

- Stan Tenen - Meru Foundation. "Meru Foundation Research: Mark R. Sunwall, Rambam Prophecy".

- The influence of Islamic Philosophy on Maimonides's thought, Diana Steigerwald Religious Studies, California State University (Long Beach) Archived 2008-01-18 at the Wayback Machine

-

For example:

Lemke, Werner E. (1987). "Life in the Present and Hope for the Future". In Mays, James Luther; Achtemeier, Paul J. (eds.). Interpreting the Prophets. Philadelphia: Fortress Press. p. 202. ISBN 9781451410471. Retrieved 2018-11-11.

The Prophet as Watchman [...] the watchman's responsibility was limited or circumscribed. He only had to issue the warning. It was the people's own responsibility to decide how to respond to it. In similar fashion the Lord has appointed Ezekiel to act as watchman over Israel, just as he had appointed other watchmen over his people in the past (cf. Jer. 6:17).

-

Buck, Charles (1802). A Theological Dictionary, Containing Definitions of All Religious Terms: A Comprehensive View of Every Article in the System of Divinity : an Impartial Count of All the Principal Denominations which Have Subsisted in the Religious World, from the Birth of Christ to the Present Day : Together with an Accurate Statement of the Most Remarkable Transactions and Events Recorded in Ecclesiastical History. Philadelphia: Edwin T. Scott (published 1823). p. 491. Retrieved 2018-11-11.

PROPHECY [...] In the Old and New Testaments, the word is not always confined to the foretelling of future events. [...] whoever speaketh unto men to edification, and exhortation, and comfort, is by St. Paul called a prophet, 1 Cor. xiv. 3.

- "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Prophecy".

-

Compare: Guiley, Rosemary (2006). "clairvoyance". The Encyclopedia of Magic and Alchemy. Infobase Publishing. p. 59. ISBN 9781438130002. Retrieved 2015-01-10.

Clairvoyance has been a valued skill in divination, prophecy, and magic since ancient times.

- "FindArticles.com - CBSi". Archived from the original on 2012-07-08.

- Schechter, Solomon; Mendelsohn, S. "PROPHET, FALSE". Jewish Encyclopedia. JewishEncyclopedia.com. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- Smith, Peter (2000). "Bahá'u'lláh – Theological Status". A concise encyclopedia of the Bahá'í Faith. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. pp. 78–79. ISBN 1-85168-184-1.

- Hatcher, W.S.; Martin, J.D. (1998). The Bahá'í Faith: The Emerging Global Religion. San Francisco: Harper & Row. pp. 116–123. ISBN 0-87743-264-3.

- Smith, Peter (2000). "Bahá'u'lláh – Life". A concise encyclopedia of the Bahá'í Faith. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. pp. 73. ISBN 1-85168-184-1.

- Smith, Peter (2000). "Maid of Heaven". A concise encyclopedia of the Bahá'í Faith. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. pp. 230. ISBN 1-85168-184-1.

- Korea: a religious history, James Huntley Grayson, p. 34

- Walter Brueggemann, The Prophetic Imagination, (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1978), 13.

- F.W.Dillstone; Christianity and Symbolism; London 1955, p275; referenced in 'The function of prophetic drama' in "The place is too small for us": the Israelite prophets in recent scholarship, by R. P. Gordon, 1995 Eisenbrauns, (cf Galatians 4:24)

- Dialogue with Trypho, Critical edition by Philippe Bobichon, Editions universitaires de Fribourg, 2003, 51, 1-3; 119, 1-5 text online ; Philippe Bobichon, "Salomon et Ezéchias dans l'exégèse juive des prophéties royales et messianiques, selon Justin Martyr et les sources rabbiniques", Tsafon 44, 2002-2003, pp. 149-165 online .

- Eusebius of Caesarea, Church History, Book V, Chapter 16 & 18 Montanus...became beside himself, and being suddenly in a sort of frenzy and ecstasy, he raved, and began to babble and utter strange things, prophesying in a manner contrary to the constant custom of the Church handed down by tradition from the beginning.... His actions and his teaching show who this new teacher is. This is he who taught the dissolution of marriage; who made laws for fasting; who named Pepuza and Tymion, small towns in Phrygia, Jerusalem, wishing to gather people to them from all directions; who appointed collectors of money; who contrived the receiving of gifts under the name of offerings; who provided salaries for those who preached his doctrine, that its teaching might prevail through gluttony.

- History of the Church of God Ministry of Jesus Christ International (official page)

- Hamon, Bill; Roberts, Oral (October 2010). Prophets and Personal Prophesy. God's Prophetic Voice Today. Guidelines for Receiving, Understanding, Fulfilling God's Personal Word to You. ISBN 9780768412802.

- Wagner, C. Peter (2000). "Emanuele Cannistraci Had Told Me". Apostles and Prophets: The Foundation of the Church. pp. 118, 123. ISBN 9780800797324.

[P]rophesy from Emanuele Cannistraci ... in 1996 ... 'When you break from your present position as professor and instructor, you are going to be a pastor to pastors, an apostolic leader to a whole new breed of men and women'... this explains why I received no revelation of WLI until the day I resigned from Fuller." "Who are the Prophets on the Apostolic Council of Prophetic Elders? ... Emanuele Cannistraci ...

- Campo, Juan Eduardo (2009). Encyclopedia of Islam. Infobase Publishing. pp. 559–560. ISBN 9780816054541. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- Quran 30:47

- Shaatri, A. I. (2007). Nayl al Rajaa' bisharh' Safinat an'najaa'. Dar Al Minhaj.

- "BBC - Religions - Islam: Basic articles of faith". Archived from the original on 13 August 2018. Retrieved 2018-10-05.

- Quran 2:285

- The Corruption of the Bible – A Fact Attested by the Quran" The True Call Archived 2012-09-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Hirsch, Emil G.; McCurdy, J. Frederic; Jacobs, Joseph. "PROPHETS AND PROPHECY". Jewish Encyclopedia. JewishEncyclopedia.com. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- Gaon, Vilna. "Babylonian Talmud". San.11a, Yom.9a/Yuch.1.14/Kuz.3.39, 65, 67/Yuch.1/Mag.Av.O.C.580.6.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - The Guide for the Perplexed /Part II/Chapter XXXIX

- The Guide for the Perplexed (Friedlander)/Part II/Chapters#CHAPTER XLV

- p.27, Helm

- "Dogrib prophecy".

- Lemesurier, Peter, The Unknown Nostradamus, 2003

- Hines, Terence. (2003). Pseudoscience and the Paranormal. Prometheus Books. pp. 66-73. ISBN 1-57392-979-4

- Pickover, Clifford A. (2001). Dreaming the Future: The Fantastic Story of Prediction. Prometheus Books. pp. 363-388. ISBN 1-57392-895-X

- Forshaw, Mark. (2012). Critical Thinking for Psychology. Wiley. pp. 46-48. ISBN 978-1-4051-9118-0

- Whitcomb, Bill. (2004). The Magician's Companion: A Practical & Encyclopedic Guide to Magical & Religious Symbolism. Llewellyn Publications. pp. 530-531. ISBN 0-87542-868-1

- "Skeptic report, Prophesies for dummies by Allan Glenn". Archived from the original on 2017-06-26. Retrieved 2018-01-15.

- Deikman, A. J. (1982). The Observing self: Mysticism and psychotherapy. Boston: Beacon Press. p. 21. ISBN 0-8070-2950-5.

- Poloma, Margaret (2003). Main street mystics: The Toronto blessing & reviving Pentecostalism. Walnut Creek, CA: Alta Mira Press. p. 115. ISBN 0-7591-0353-4.

- Poloma, M. M. (2003). Main street mystics: The Toronto blessing & reviving Pentecostalism. Walnut Creek, CA: Alta Mira Press. p. 126. ISBN 0-7591-0353-4.

- Jaynes, J. (1976). Main street mystics: The origins of consciousness in the breakdown of the bicameral mind. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 74.

- Pearce, J. C. (2002–2004). The Biology of Transcendence: A blueprint of the human spirit. Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions International. p. 191. ISBN 0-89281-990-1.

- Pearce, J. C. The Biology of Transcendence. p. 192.

- Pearce, J. C. The Biology of Transcendence. pp. 194 & 196.

- "The Fallacy of Prophecy - the Beginner". Archived from the original on 2011-04-25. Retrieved 2011-04-19.

- Foundation, Poetry (2020-08-22). "Poetry and Prophecy by A.E. Stallings". Poetry Foundation. Retrieved 2020-08-22.

- Pettit, Jonathan (2006). "Review of Chinese Poetry and Prophecy: The Written Oracle in East Asia". China Review International. 13 (2): 512–517. ISSN 1069-5834. JSTOR 23732747.

- Franke, William (2016-05-09). "Poetry, Prophecy, and Theological Revelation". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.205. ISBN 978-0-19-934037-8. Retrieved 2020-08-22.

- "Poems of Political Prophecy: Introduction | Robbins Library Digital Projects". d.lib.rochester.edu. Retrieved 2020-08-22.

- Armenti, Peter (2017-10-24). "Poetry, and history, and prophecy! Oh, my! | From the Catbird Seat: Poetry & Literature at the Library of Congress". blogs.loc.gov. Retrieved 2020-08-22.

- Poets, Academy of American. "Prophecy by Dana Gioia - Poems | Academy of American Poets". poets.org. Retrieved 2020-08-22.

- Foundation, Poetry (2020-08-22). "The Prophets Really Prophesy as Mystics the Commentators Merely by Statistics by Robert Frost". Poetry Magazine. Retrieved 2020-08-22.

- Foundation, Poetry (2020-08-22). "Advice to a Prophet by Richard Wilbur". Poetry Foundation. Retrieved 2020-08-22.

- Foundation, Poetry (2020-08-22). "from The Prodigal by Derek Walcott | [Desire and disease commingling] by Derek Walcott | [O Serbian sibyl, prophetess] by Derek Walcott". Poetry Magazine. Retrieved 2020-08-22.

Further reading

- Alcalay, Reuben. 1996. The Complete Hebrew – English dictionary, Hemed Books, New York. ISBN 978-965-448-179-3

- Ashe, Geoffrey. 2001. Encyclopedia of Prophecy, Santa Barbara, ABC-Clio.

- Aune, David E. (1983). "Ancient Israelite Prophecy and Prophecy in Early Judaism". Prophecy in Early Christianity and the Ancient Mediterranean World. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans. pp. 81–147. ISBN 978-0-8028-0635-2. OCLC 9555379.

- Jürgen Beyer. 2002. 'Prophezeiungen', Enzyklopädie des Märchens: Handwörterbuch zur historischen und vergleichenden Erzählforschung [N.B.: In English renders as "Encyclopedia of the fairy tale: Handy dictionary for historical and comparative tale research"]. Berlin & New York: Walter de Gruyter. In vol. 10, on col. 1419–1432.

- Stacey Campbell. 2008. Ecstatic Prophecy. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Chosen Books/Baker Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8007-9449-1.

- Marcus Tullius Cicero. 1997. De divinatione. Trans. Arthur Stanley Pease. Darmstadt: Wissenschaflliche Buchgesellschaft.

- Dawson, Lorne L. (October 1999). "When Prophecy Fails and Faith Persists: A Theoretical Overview" (PDF). Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions. Berkeley: University of California Press. 3 (1): 60–82. doi:10.1525/nr.1999.3.1.60. ISSN 1092-6690. LCCN 98656716. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- Leon Festinger, Henry W. Riecken, Stanley Schachter. (1956). When Prophecy Fails: A Social and Psychological Study of a Modern Group that Predicted the Destruction of the World. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 1-59147-727-1

- Christopher Forbes. 1997. Prophecy and Inspired Speech: in Early Christianity and Its Hellenistic Environment. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson. ISBN 1-56563-269-9.

- Clifford S. Hill. 1991. Prophecy, Past and Present: an Exploration of the Prophetic Ministry in the Bible and the Church today. Ann Arbor, Mich.: Vine. ISBN 0-8028-0635-X.

- June Helm. (1994). Prophecy and Power among the Dogrib Indians. University of Nebraska Press.

- Clifford A. Pickover. (2001). Dreaming the Future: The Fantastic Story of Prediction. Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-57392-895-X

- James Randi. (1993). The Mask of Nostradamus: Prophecies of the World's Famous Seer. Prometheus Books. ISBN 0-87975-830-9

- H. H. Rowley. 1956. Prophecy and Religion in Ancient China and Israel. New York: Harper & Brothers. vi, 154 p.

- Thomas George Tucker. 1985. Etymological Dictionary of Latin. Ares Publishers. ISBN 978-0-89005-172-6

External links

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Scientific American, "Grimmer's Prophecy", 4 September 1880, p. 149