Bambi, a Life in the Woods

Bambi, a Life in the Woods (German title: Bambi: Eine Lebensgeschichte aus dem Walde) is a 1923 Austrian coming-of-age novel written by Felix Salten and originally published in Berlin by Ullstein Verlag. The novel traces the life of Bambi, a male roe deer, from his birth through childhood, the loss of his mother, the finding of a mate, the lessons he learns from his father, and the experience he gains about the dangers posed by human hunters in the forest.

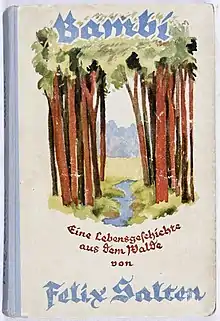

First edition cover of the original publication | |

| Author | Felix Salten |

|---|---|

| Original title | Bambi: Eine Lebensgeschichte aus dem Walde |

| Translator | Whittaker Chambers |

| Illustrator | Kurt Wiese |

| Country | Austria |

| Language | German |

| Genre | Fiction |

| Publisher | Ullstein Verlag |

Publication date | 1923 |

Published in English | 1928 |

| Media type | Print (hardcover) |

| OCLC | 2866578 |

| Followed by | Bambi's Children |

An English translation by Whittaker Chambers was published in North America by Simon & Schuster in 1928,[1] and the novel has since been translated and published in over thirty languages around the world. Salten published a sequel, Bambi's Children, in 1939.

The novel was well received by critics and is considered a classic, as well as one of the first environmental novels. It was adapted into a theatrical animated film, Bambi, by Walt Disney Productions in 1942, as well as two Russian live-action adaptations in 1985 and 1986, a ballet in 1987, and a stage production in 1998. Another ballet adaptation was created by an Oregon troupe, but never premiered. Janet Schulman published a children's picture book adaptation in 2000 that featured realistic oil paintings and many of Salten's original words.

Plot

Bambi is a roe deer fawn born in a thicket in late spring one year. Over the course of the summer, his mother teaches him about the various inhabitants of the forest and the ways deer live. When she feels he is old enough, she takes him to the meadow, which he learns is both a wonderful but also dangerous place as it leaves the deer exposed and in the open. After some initial fear over his mother's caution, Bambi enjoys the experience. On a subsequent trip Bambi meets his Aunt Ena and her twin fawns Faline and Gobo. They quickly become friends and share what they have learned about the forest. While they are playing, they encounter princes, male deer, for the first time. After the stags leave, the fawns learn that those were their fathers, but that the fathers rarely stay with or speak to the females and young.

As Bambi grows older, his mother begins to leave him alone. While searching for her one day, Bambi has his first encounter with "He" the animals' term for humans – which terrifies him. The man raises a firearm and aims at him; Bambi flees at top speed, joined by his mother. After he is scolded by a stag for crying for his mother, Bambi gets used to being alone at times. He later learns the stag is called the "Old Prince", the oldest and largest stag in the forest, who is known for his cunning and aloof nature. During the winter, Bambi meets Marena, a young doe, Nettla, an old doe who no longer bears young, and two princes, Ronno and Karus. Mid-winter, hunters enter the forest, killing many animals including Bambi's mother. Gobo also disappears and is presumed dead.

After this, the novel skips ahead a year, noting that Bambi, now a young adult, was cared for by Nettla and that when he got his first set of antlers he was abused and harassed by the other males. It is summer and Bambi is now sporting his second set of antlers. He is reunited with his cousin Faline. After he battles and defeats first Karus then Ronno, Bambi and Faline fall in love with each other. They spend a great deal of time together. During this time, the Old Prince saves Bambi's life when he nearly runs towards a hunter imitating a doe's call. This teaches the young buck to be cautious about blindly rushing toward any deer's call. During the summer, Gobo returns to the forest, having been raised by a man who found him collapsed in the snow during the hunt where Bambi's mother was killed. While his mother and Marena welcome him and celebrate him as a "friend" of man, the Old Prince and Bambi pity him. Marena becomes his mate, but several weeks later Gobo is killed when he approaches a hunter in the meadow, falsely believing the halter he wore would keep him safe from all men.

As Bambi continues to age, he begins spending most of his time alone, including avoiding Faline though he still loves her in a melancholic way. Several times he meets with the Old Prince, who teaches him about snares, shows him how to free another animal from one, and encourages him not to use trails, to avoid the traps of men. When Bambi is later shot by a hunter, the Prince shows him how to walk in circles to confuse the man and his dogs until the bleeding stops, then takes him to a safe place to recover. They remain together until Bambi is strong enough to leave the safe haven again. When Bambi has grown gray and is "old", the Old Prince shows him that man is not all-powerful by showing him the dead body of a man who was shot and killed by another man. When Bambi confirms that he now understands that "He" is not all-powerful, and that there is "Another" over all creatures, the stag tells him that he has always loved him and calls him "my son" before leaving.

At the end of the novel, Bambi meets with twin fawns who are calling for their mother and he scolds them for not being able to stay alone. After leaving them, he thinks to himself that the girl fawn reminded him of Faline, and that the male was promising and that Bambi hoped to meet him again when he was grown.

Publication history

Felix Salten, himself an avid hunter,[2][3] penned Bambi: Eine Lebensgeschichte aus dem Walde after World War I, targeting an adult audience.[4] The novel was first published in Vienna in serialized form in the newspaper the Neue Freie Presse from 15 August to 21 October 1922,[5] and as a book in Germany by Ullstein Verlag in 1923, and republished in 1926 in Vienna.[6][7]

Translations

Max Schuster, a German Jewish emigré and co-founder of Simon & Schuster, led the effort to publish Bambi in English.[8] Clifton Fadiman, an editor there, engaged his Columbia University classmate Whittaker Chambers to translate it.[9] Simon & Schuster published this first English edition in 1928, with illustrations by Kurt Wiese, under the title Bambi: A Life in the Woods.[6][10] The New York Times Book Review praised the prose as "admirably translated" that made the book "literature of a high order."[11][8] The translation immediately became "a Book-of-the-Month Club hit."[12] Simon & Schuster printed a first-run of 75,000 copies[13] and sold more than 650,000 copies between 1928 and 1942.[8] (Jonathan Cape published the book in the UK starting in 1928 as well.[14]) Chambers’ translation has been reprinted repeatedly with different illustrations.[15] Bambi, along with Salten's Fifteen Rabbits and The City Jungle, all translated by Chambers, remain in print from Simon & Schuster.[16] In 2015, an Austrian scholar voiced objections to Simon & Schuster's "publication strategies" and "marketing strategy," as well as Chambers' translation for "opening the possibility for the story to be understood less as a human story about persecution, expulsion or assimilation and more as an animal story conveying a strong message about the protection of animals and the necessity of conservation."[13]

A translation by Hannah Correll was published in 2019 by Clydesdale Press.[15] A translation by Jack Zipes was published in 2022 by Princeton University Press.[17] Zipes commented the conversation between animals is "reminiscent of Austrian German you'd hear in cafes around Vienna. The original translation didn't capture that and I hope mine does,"[18][19] while a Chambers' grandchild countered that the 1928 translation is more poetic.[20] One reviewer wrote: "Chambers and Zipes differ moderately in style, with Zipes cleaving more faithfully to the German ("polecat") and Chambers privileging his American audience ("ferret"). An aim of Zipes’ translation is to restore Salten's more overt anthropomorphism, which Chambers softened. To a reader familiar with the 1928 translation, some of Zipes' more faithful anthropomorphic choices are jarring; it feels odd to read that a fawn "yelled," for example.[21] A translation by Damion Searls will be published in mid-2022 by The New York Review of Books.[22] The translations were reviewed in various newspapers and magazines.[23][18][24][19]

Formats

Over 200 editions of the novel have been published, with almost 100 German and English editions alone, and numerous translations and reprintings in over 30 languages.[25] It has also been published in a variety of formats, including printed medium, audiobook, Braille, and E-book formats.[26]

Copyright dispute

When Salten originally published Bambi in 1923, he did so under Germany's copyright laws, which required no statement that the novel was copyrighted. In the 1926 republication, he did include a United States copyright notice, so the work is considered to have been copyrighted in the United States in 1926. In 1936, Salten sold some film rights to the novel to MGM producer Sidney Franklin who passed them on to Walt Disney for the creation of a film adaptation. After Salten's death in 1945, his daughter Anna Wyler inherited the copyright and renewed the novel's copyrighted status in 1954 (U.S. copyright law in effect at the time provided for an initial term of 28 years from the date of first publication in the U.S., which could be extended for an additional 28 years provided the copyright holder filed for renewal before the expiration of the initial copyr|ight). In 1958, she formulated three agreements with Disney regarding the novel's rights. Upon her death in 1977, the rights passed to her husband, Veit Wyler, and her children, who held on to them until 1993 when he sold the rights to the publishing house Twin Books. Twin Books and Disney disagreed on the terms and validity of Disney's original contract with Anna Wyler and Disney's continued use of the Bambi name.[7]

When the two companies were unable to reach a solution, Twin Books filed suit against Disney for copyright infringement. Disney argued that because Salten's original 1923 publication of the novel did not include a copyright notice, by American law it was immediately considered a public domain work. It also argued that as the novel was published in 1923, Anna Wyler's 1954 renewal occurred after the deadline and was invalid.[7][27] The case was reviewed by the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, which ruled that the novel was copyrighted upon its publication in 1923, and not a public domain work then. However, in validating 1923 as the publication date, this confirmed Disney's claim that the copyright renewal was filed too late and the novel became a public domain work in 1951.[7]

Twin Books appealed the decision, and in March 1996 the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit reversed the original decision, stating that the novel was a foreign work in 1923 that was not in its home country's public domain when published, therefore the original publication date could not be used in arguing American copyright law. Instead, the 1926 publication date, the first in which it specifically declared itself to be copyrighted in the United States, is considered the year when the novel was copyrighted in America. Anna Wyler's renewal was therefore timely and valid, and Twin Books' ownership of the copyright was upheld.[27]

The Twin Books decision is still regarded as controversial by many copyright experts.[28][29] David Nimmer, in a 1998 article, argued that the Twin Books ruling meant that an ancient Greek epic, if only published outside the U.S. without the required formalities, would be eligible for copyright protection. Although Nimmer concluded that Twin Books required this finding (within the Ninth Circuit), he characterized the result as "patently absurd."[30]

The American copyright of the novel expired on January 1, 2022,[28] while in Austria and other countries of the European Union it entered the public domain on January 1, 2016.

Sequel

While living in exile in Switzerland, after being forced to flee Nazi-occupied Austria, Salten wrote a sequel to Bambi that follows the birth and lives of Bambi's twin offspring, Geno and Gurri.[31] The young fawns interact with other deer, and are educated and watched over by Bambi and Faline as they grow. They also learn more about the ways of man, including both hunters and the gamekeeper seeking to protect the deer. Due to Salten's exiled status — he had lost his Austrian publisher Paul Zsolnay Verlag — the English translation of the novel was published first, in the United States in 1939 by Bobbs-Merrill; it would take a year before the sequel was published in the original German language in Switzerland by his new publisher.[32]

Reception

In the United States, the 1928 translation of Bambi was "hugely popular,"[33] selling 650,000 copies by 1942.[34] When Felix Salten visited the United States as a member of a European delegation of journalists in May–July 1930, he was greeted warmly because of Bambi wherever the delegation went, as was testified by the Finnish member of the delegation, Urho Toivola.[35] In his own travel book, Salten did not boast about this; only when describing his visit to a “Negro college” of Atlanta, he mentions passingly that the children praised his books.[36]

In 1936 Nazi Germany however, the government banned the original as "political allegory on the treatment of Jews in Europe."[33] Many copies of the novel were burned, making original first editions rare and difficult to find.[37]

"The reader is made to feel deeply and thrillingly the terror and anguish of the hunted, the deceit and cruelty of the savage, the patience and devotion of the mother to her young, the fury of rivals in love, the grace and loneliness of the great princes of the forest. In word pictures that are sometimes breath-taking the author draws the forest in all its moods--lashed into madness by storms, or white and silent under snow, or whispering and singing to itself at daybreak.

—Louise Long, Dallas Morning News, October 30, 1938[38]

In his foreword of the novel, John Galsworthy called it a "delicious book - delicious not only for children but for those who are no longer so fortunate" and a "little masterpiece" that shows a "delicacy of perception and essential truth". He observed that while reading the galley proof of the novel while crossing the English Channel, he, his wife, and his nephew read each page in turn over the course of three hours in "silent absorption."[39]

Among US reviewers, New York Times reviewer John Chamberlain praised Salten's "tender, lucid style" that "takes you out of yourself".[11] He felt that Salten captured the essence of each of the creatures as they talked, catching the "rhythm of the different beings who people his forest world" and showed particular "comprehension" in detailing the various stages of Bambi's life.[11] He also considered the English translation "admirably" done.[11] A reviewer for Catholic World praised the approach of the subject, noting that it was "marked by poetry and sympathy [with] charming reminders of German folklore and fairy tale" but disliked the "transference of certain human ideals to the animal mind" and the vague references to religious allegory.[40] The Boston Transcript called it a "sensitive allegory of life".[41] The Saturday Review considered it "beautiful and graceful" piece that showed a rare "individuality".[41] Isabel Ely Lord, reviewing the novel for the American Journal of Nursing, called the novel a "delightful animal story" and Salten a "poet" whose "picture of the woods and its people is an unforgettable one."[42] In comparing Bambi to Salten's later work Perri—in which Bambi makes a brief cameo—Louise Long of the Dallas Morning News considered both to be stories that "quietly and completely [captivate] the heart". Long felt the prose was "poised and mobile and beautiful as poetry" and praises Salten for his ability to give the animals seemingly human speech while not "[violating] their essential natures."[38] Vicky Smith of Horn Book Magazine felt the novel was gory compared to the later Disney adaptation and called it a "weeper". While criticizing it as one of the most esteemable anti-hunting novels available, she concedes the novel is not easily forgettable and praises the "linchpin scene" where Bambi's mother dies, stating "the understated conclusion of that scene, 'Bambi never saw his mother again,' masterfully evokes an uncomplicated emotional response".[43] She questions Galsworthy's recommendation of the novel to sportsmen in the foreword, wondering "how many budding sportsmen might have had conversion experiences in the face of Salten's unrelieved harangue and how many might have instead become alienated."[43] In comparing the novel to the Disney film, Steve Chapple of Sports Afield felt that Salten viewed Bambi's forest as a "pretty scary place" and the novel as a whole had a "lot of dark adult undertones."[44] Interpreting it as an allegory for Salten's own life, Chapple felt Salten came across as "a little morbid, a bleeding heart of a European intellectual."[44] A half century later,The Wall Street Journal's James P. Sterba also considered it an "antifascist allegory" and sarcastically notes that "you'll find it in the children's section at the library, a perfect place for this 293-page volume, packed as it is with blood-and-guts action, sexual conquest and betrayal" and "a forest full of cutthroats and miscreants. I count at least six murderers (including three child-killers) among Bambi's associates."[45]

Among UK reviews, the Times Literary Supplement stated that the novel is a "tale of exceptional charm, though untrustworthy of some of the facts of animal life."[41][46]

Impact

Some critics have argued that Bambi is one of the first environmental novels.[6][47]

Adaptations

Walt Disney animated film

With World War II looming, Max Schuster aided the Jewish Salten's flight from Nazi controlled Austria and Nazi Germany and helped introduce him, and Bambi, to Walt Disney Productions.[6] Sidney Franklin, a producer and director at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, purchased the film rights in 1933, initially desiring to make a live-action adaptation of the work.[7] Deciding such a film would be too difficult to make, he sold the rights to Walt Disney in April 1937 in hopes of it being adapted into an animated film instead. Disney began working on the film immediately, intending it to be the company's second feature-length animated film and his first to be based on a specific, recent work.[48]

The original novel, written for an adult audience, was considered too "grim" and "somber" for the young audience Disney was targeting, and with the work required to adapt the novel, Disney put production on hold while it worked on several other projects.[48] In 1938, Disney assigned Perce Pearce and Carl Fallberg to develop the film's storyboards, but attention was soon drawn away as the studio began working on Fantasia.[48] Finally, on 17 August 1939, production on Bambi began in earnest, although it progressed slowly due to changes in the studio personnel, location and the methodology of handling animation at the time. The writing was completed in July 1940, by which time the film's budget had swelled to $858,000.[49] Disney was later forced to slash 12 minutes from the film before final animation, to save costs on production.[49]

Heavily modified from the original novel, Bambi was released to theaters in the United States on 8 August 1942. Disney's version severely downplays the naturalistic and environmental elements found in the novel, giving it a lighter, friendlier feeling.[4][6] The addition of two new characters, Thumper the Rabbit and Flower the Skunk, two sweet and gentle forest creatures, contributed to giving the film the desired levity. Considered a classic, the film has been called "the crowning achievement of Walt Disney's animation studio" and was named as the third best film in the animation genre of the AFI's 10 Top 10 "classic" American film genres.[50]

Russian live-action films

In 1985, a Russian-language live-action adaptation, Russian: Детство Бемби (Detstvo Bembi, lit. Bambi's Childhood), was produced and released in VHS format in the Soviet Union by Gorky Film Studios.[51][52] It was directed by Natalya Bondarchuk, who also co-wrote the script with Yuri Nagibin, and featured music by Boris Petrov. Natalya 's son Ivan Burlyayev and her husband Nikolay Burlyaev starred as the young and adolescent Bambi, respectively, while Faline (renamed Falina) was portrayed by Yekaterina Lychyova as a child and Galina Belyayeva as an adult. In this adaptation, the film starts using animals, changes to using human actors, then returns to using animals for the ending.[52]

A sequel, Russian: Юность Бемби (Yunost Bembi), lit. Bambi's Youth, followed in 1986 with Nikolay and Galina reprising their voice roles as Bambi and Falina. Featuring over 100 species of live animals and filmed in various locations in Crimea, Mount Elbrus, Latvia and Czechoslovakia, the film follows new lovers Bambi and Felina as they go on a journey in search of a life-giving flower.[53] Both films were released to Region 2 DVD with Russian and English subtitle options by the Russian Cinema Council in 2000. The first film's DVD also included a French audio soundtrack, while the second contained French subtitles instead.[51][53]

Ballet

The Estonian composer Lydia Auster composed the ballet Bambi in 1986 which was premièred in Tartu, Vanemuine theater, in 1987.[54]

The Oregon Ballet Theatre adapted Bambi into an evening-length ballet entitled Bambi: Lord of the Forest. It was slated to premiere in March 2000 as the main production for the company's 2000–2001 season.[55][56] A collaboration between artistic director James Canfield and composer Thomas Lauderdale, the ballet's production was to be an interpretation of the novel rather than the Disney film.[55] In discussing the adaptation, Canfield stated that he was given a copy of the novel as a Christmas present and found it to be a "classic story about coming of age and a life cycle."[55] He went on to note that the play was inspired solely by the novel and not the Disney film.[55] After the initial announcements, the pair began calling the work The Collaboration, as Disney owns the licensing rights for the name Bambi and they did not wish to fight for usage rights.[55] The local press began calling the ballet alternative titles, including Not-Bambi which Canfield noted to be his favorite, out of derision at Disney.[55][56] Its premiere was delayed for unexplained reasons, and it has yet to be performed.[56]

Theater

Playwright James DeVita, of the First Stage Children's Theater, created a stage adaptation of the novel.[57] The script was published by Anchorage Press Plays on 1 June 1997.[57][58] Crafted for young adults and teenagers and retaining the title Bambi—A Life in the Woods, it has been produced around the United States at various venues. The script calls for an open-stage setup, and utilizes at least nine actors: five male and four female, to cover the thirteen roles.[58] The American Alliance Theatre and Education awarded the work its "Distinguished Play Award" for an adaptation.[59][60]

Book

In 1999, the novel was adapted into an illustrated hardback children's book by Janet Schulman, illustrated by Steve Johnson and Lou Fancher, and published by Simon & Schuster as part of its "Atheneum Books for Young Readers" imprint. In the adaptation, Schulman attempted to retain some of the lyrical feel of the original novel. She notes that rather than rewrite the novel, she "replicated Salten's language almost completely. I reread the novel a number of times and then I went through and highlighted the dialogue and poignant sentences Salten had written."[6] Doing so retained much of the novel's original lyrical feel, though the book's brevity did result in a sacrifice of some of the "majesty and mystery" found in the novel.[4] The illustrations were created to appear as realistic as possible, using painted images rather than sketches.[4][6] In 2002, the Schulman adaptation was released in audiobook format by Audio Bookshelf, with Frank Dolan as the reader.[47]

See also

- Bambi Awards

- Bambi effect

- Bambi's Children

- Fifteen Rabbits

References

- Chambers, Whittaker (1952). Witness. Random House. pp. 56, 239. ISBN 0-89526-571-0.

- Sax, Boria (2001), The Mythical Zoo: An Encyclopedia of Animals in World Myth, Legend, and Literature, ABC-CLIO, p. 146, ISBN 1-5760-7612-1

- Jessen, Norbert (2012-02-26). "Israel: Zu Besuch bei den Erben von Bambi". WELT (in German). Archived from the original on 2018-12-18. Retrieved 2018-12-18.

- Spires, Elizabeth (21 November 1999). "The Name Is the Same: Two children's classics have been adapted and simplified for today's readers. A third has been republished intact". The New York Times: 496.

- Eddy, Beverley Driver (2010). Felix Salten: Man of Many Faces. Riverside (Ca.): Ariadne Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-1-57241-169-2.

- Di Marzo, Cindi (25 October 1999). "A New Look for Bambi". Publishers Weekly. 246 (43): 29.

- "U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals Twin Books v Disney". FindLaw. 20 May 1996. Archived from the original on 19 June 2009. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- Katz, Maya Balakirsky (November 2020). "Bambi Abroad, 1924-1954". AJS Review. Association for Jewish Studies. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- "Translations". WhittakerChambers.org. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- Lohrke, Eugene (8 July 1928). "A Tone Poem." New York Herald Tribune. Page K3.

- Chamberlain, John R. (8 July 1928). "Poetry and Philosophy in A Tale of Forest Life: In Bambi, Felix Salten Writes an Animal Story that is Literature of a High Order". The New York Times. pp. 53–54. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- Pokorn, Nike K. (2012). "Bambi". Post-Socialist Translation Practices: Ideological Struggle in Children's Literature. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 75. ISBN 978-9027224538. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- Strümper-Krobb, Sabine (2015). "'I particularly recommend it to sportsmen.' Bambi in America: The Rewriting of Felix Salten's Bambi". Austrian Studies. 23: 123–142. doi:10.5699/austrianstudies.23.2015.0123. JSTOR 10.5699/austrianstudies.23.2015.0123.

- Patten, Fred (2012). "Bambi". Furry Tales: A Review of Essential Anthropomorphic Fiction. McFarland. p. 31. ISBN 9781476675985. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- Salten, Felix (2019). Bambi. Translated by Hannah Correll. New York: Clydesdale Press. ISBN 978-1-949846-05-8.

- "Whittaker Chambers". Simon & Schuster. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- The Original Bambi. Princeton University Press. 2022. ISBN 9780691197746. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- Ferguson, Donna (25 December 2021). "Bambi: cute, lovable, vulnerable ... or a dark parable of antisemitic terror?". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- Joanne O’Sullivan (January 13, 2022). "New Bambi Translation Reveals the Dark Origins of the Disney Story". Publishers Weekly. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

- Chambers, David (21 January 2022). "'Bambi,' Whittaker Chambers and the Art of Translation". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- Cohen, Nan (2 February 2022). "A New Translation Emphasizes "Bambi" as a Parable for European Antisemitism". Electric Literature. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- "Bambi". New York Review of Books. 2022. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- "'The Original Bambi' Review: Afterlife of a Fawn". Wall Street Journal. 14 January 2022. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- Schulz, Kathryn (17 January 2022). "Eat, Prey, Love: Bambi" Is Even Bleaker Than You Thought". New Yorker. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- Felix Salten: A Preliminary Bibliography of His Works in Translation. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- Formats and Editions of Bambi: Eine Lebensgeschichte aus dem Walde. WorldCat. OCLC 2866578.

- Schons, Paul (September 2000). "Bambi, the Austrian Deer". Germanic-American Institute. Archived from the original on 8 August 2008. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- Fishman, Stephen (2008). The Copyright Handbook: What Every Writer Needs to Know (10th ed.). Berkeley, CA: Nolo. p. 284. ISBN 978-1-4133-0893-8.

- "Copyright Term and the Public Domain in the United States". Cornell Copyright Information Center. Archived from the original on April 10, 2011. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- Nimmer, David (April 1998). "An Odyssey Through Copyright's Vicarious Defenses". New York University Law Review. 73 (1).

- Flippo, Hyde. "Felix Salten (Siegmund Salzmann, 1869–1945)". The German-Hollywood Connection. The German Way and More. Archived from the original on 6 August 2007. Retrieved 20 July 2008.

- Eddy, Beverley Driver (2010). Felix Salten: Man of Many Faces. Riverside (Ca.): Ariadne Press. pp. 291–293. ISBN 978-1-57241-169-2.

- Lambert, Angela (2008). The Lost Life of Eva Braun. Macmillan. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-312-37865-3.

- "Disney Films Bambi, First Cartoon Novel". Dallas Morning News. October 25, 1942. p. 11.

- Toivola, Urho (1932). Aurinkoista Amerikkaa. Helsinki: WSOY. pp. 191–192. LCCN unk81005545.

- Salten, Felix (1931). Fünf Minuten Amerika. Wien: Paul Zsolnay Verlag. p. 56. LCCN 31029185.

- "Salten, Felix "Bambi: Eine Lebensgeschichte aus dem Walde"". International League of Antiquarian Booksellers. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- Long, Louise (October 30, 1938). "Fanciful Allegory Delineates Wild Life in Austrian Forests". Dallas Morning News. p. 4.

- Salten, Felix (1988). "Foreword, dated 16 March 1928". Bambi. foreword by John Galsworthy. Simon & Schuster. p. 5. ISBN 0-671-66607-X.

- MCM (1928). "New Books". Catholic World. 128 (763–768): 376–377. ISSN 0008-848X.

- Book Review Digest, Volume 24. H.W. Wilson Company. 1929. p. 677.

- Lord, Isabel Ely (March 1929). "Books You Will Enjoy". American Journal of Nursing. 29 (3): 371. doi:10.1097/00000446-192903000-00055. ISSN 0002-936X. S2CID 76339481.

- Smith, Vicky (September–October 2004). "A-Hunting We Won't Go". Horn Book Magazine. 80 (5): 521–531. ISSN 0018-5078.

- Chapple, Steve (1993). "The Bambi syndrome". Sports Afield. 217 (5): 128. Bibcode:1993Natur.364..111K. doi:10.1038/364111a0. ISSN 0038-8149. S2CID 32825622.

- Sterba, James P. (14 October 1997). "The Not-So Wonderful World of Bambi". The Wall Street Journal. 230 (74): A20. ISSN 0099-9660.

- Times (London) Literary Supplement. 30 August 1928. p. 618.

- "Felix Salten's Bambi (Sound Recording)". Publishers Weekly. 249 (10): 24. 11 March 2002.

- Barrier, J. Michael (2003). "Disney, 1938–1941". Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age. Oxford University Press. pp. 236, 244–245. ISBN 0-19-516729-5.

- Barrier, J. Michael (2003). "Disney, 1938–1941". Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age. Oxford University Press. pp. 269–274, 280. ISBN 0-19-516729-5.

- "AFI's 10 Top 10". American Film Institute. 17 June 2008. Archived from the original on 18 May 2010. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- "Detstvo Bembi". Ruscico. Archived from the original on 26 June 2007. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- "MRC FilmFinder—Full Record: Detstvo Bembi". University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- "Yunost Bembi". Ruscico. Archived from the original on 26 June 2007. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- Lydia Auster: Works for the Stage. Estonian Music Information Centre.

- West, Martha Ullman (February 2001). "'Bambi' clash elicits an oh, deer! from dance fans". Dance Magazine. 75 (2): 39. ISSN 0011-6009.

- West, Martha Ullman (June 2001). "Oregon Ballet's 'Bambi' Still in the woods". Dance Magazine. 75 (6): 43. ISSN 0011-6009.

- "Scripts & Plays: B". Anchorage Press Plays. Archived from the original on 24 May 2007. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- Devita, James (1995). Bambi, a Life in the Woods (Paperback). ISBN 0876023472.

- "Award Winners". American Alliance Theatre and Education. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- "James DeVita Biography". Dramatic Publishing. Archived from the original on 24 June 2010. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

External links

- Bambi: A Life in the Woods at Faded Page (Canada)

- Bambi: Eine Lebensgeschichte aus dem Walde (German) at Faded Page (Canada)

- German text of Bambi online (missing last 2 chapters as of Jan 2019). Projekt Gutenberg.