Battle of Warsaw (1920)

The Battle of Warsaw (Polish: Bitwa Warszawska, Russian: Варшавская битва, transcription: Varshavskaya bitva, also known as the Miracle on the Vistula (Polish: Cud nad Wisłą), was a series of battles that resulted in a decisive Polish victory in 1920 during the Polish–Soviet War. Poland, on the verge of total defeat, repulsed and defeated the Red Army.

| Battle of Warsaw | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Polish–Soviet War | |||||||

Clockwise from top left: Polish infantry on the move; dinner while on duty; 120 mm battery firing on Russian positions; Machine gun nest; Polish reinforcements on the way to the front; Captured Soviet flags displayed by defenders. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Supported by: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 113,000–135,000[1] | 104,000–140,000[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

4,500 dead 26,000 wounded 10,000 missing[1] Total: 40,500 |

10,000–25,000 dead 30,000 wounded 65,000–85,000 captured 30,000–35,000 interned in East Prussia[1][2] Total: 110,000–126,000 | ||||||

Location within Poland | |||||||

After the Polish Kiev Offensive, Soviet forces launched a successful counterattack in summer 1920, forcing the Polish army to retreat westward in disarray. The Polish forces seemed on the verge of disintegration and observers predicted a decisive Soviet victory.

The Battle of Warsaw was fought from August 12–25, 1920 as Red Army forces commanded by Mikhail Tukhachevsky approached the Polish capital of Warsaw and the nearby Modlin Fortress. On August 16, Polish forces commanded by Józef Piłsudski counterattacked from the south, disrupting the enemy's offensive, forcing the Russian forces into a disorganized withdrawal eastward and behind the Neman River. Estimated Russian losses were 10,000 killed, 500 missing, 30,000 wounded, and 66,000 taken prisoner, compared with Polish losses of some 4,500 killed, 10,000 missing, and 22,000 wounded.

The defeat crippled the Red Army; Vladimir Lenin, the Bolshevik leader, called it "an enormous defeat" for his forces.[3] In the following months, several more Polish follow-up victories secured Poland's independence and led to a peace treaty with Soviet Russia and Soviet Ukraine later that year, securing the Polish state's eastern frontiers until 1939.

The politician and diplomat Edgar Vincent regards this event as one of the most important battles in history on his expanded list of most decisive battles, since the Polish victory over the Soviets halted the spread of communism further westwards into Europe. A Soviet victory, which would have led to the creation of a pro-Soviet Communist Poland, would have put the Soviets directly on the eastern border of Germany, where considerable revolutionary ferment was present at the time.

Prelude

In the aftermath of World War I, Poland fought to preserve its newly regained independence, lost in the 1795 partitions of Poland, and to carve out the borders of a new multinational federation (Intermarium) from the territories of their former partitioners, Russia, Germany, and Austria-Hungary.[4]

At the same time in 1919, the Bolsheviks had gained the upper hand in the Russian Civil War, having dealt crippling blows to the Russian White Movement.[4] Vladimir Lenin viewed Poland as a bridge to bring communism to Central and Western Europe, and the Polish–Soviet War seemed the perfect way to test the Red Army's strength. The Bolshevik's speeches asserted that the revolution was to be carried to western Europe on the bayonets of Russian soldats and that the shortest route to Berlin and Paris lay through Warsaw.[5] The conflict began when Polish head of state Józef Piłsudski formed an alliance with the Ukrainian leader Symon Petlyura (on April 21, 1920) and their combined forces began to push into Ukraine, liberating Kyiv on May 7.

The two sides were embroiled in the Polish–Ukrainian War, amidst competing territorial claims. After early setbacks against Poland in 1919, the Red Army was overwhelmingly successful in a counter-offensive in early 1920 that nullified the Polish Kiev Operation, forcing a Polish retreat. By mid-1920, Poland's very survival was at stake and foreign observers expected it to collapse at any moment.[6] The Russian strategy called for a mass push toward the Polish capital, Warsaw. Its capture would have had a major propaganda effect for the Russian Bolsheviks, who expected the fall of the Polish capital not only to undermine the morale of the Poles, but to spark an international series of communist uprisings and clear the way for the Red Army to join the German Revolution.

The Russian 1st Cavalry Army under Semyon Budyonny broke through Polish lines in early June.[7] The effects of that were dramatic; Budyonny's success resulted in a collapse of all Polish fronts. On July 4, Mikhail Tukhachevsky's Western Front began an all-out assault in Belarus from the Berezina River, forcing Polish forces to retreat. On July 19 the Red Army seized Grodno, on July 22 the Brześć Fortress was captured and on July 28, it reached Białystok.[1][7] In early August, Polish and Soviet delegations met at Baranavichy and exchanged notes, but their talks came to nothing.[8]

Orders of battle

Polish

3 Fronts (Northern, Central, Southern), 7 Armies, a total of 32 divisions: 46,000 infantry; 2,000 cavalry; 730 machine guns; 192 artillery batteries; and several units of (mostly FT-17) tanks.

| Northern Front Haller | Central Front Rydz-Śmigły | Southern Front Iwaszkiewicz |

|---|---|---|

| 5th Army Sikorski | 4th Army Skierski | 6th Army Jędrzejewski |

| 1st Army Latinik | 3rd Army Zieliński | Ukrainian Army Petliura |

| 2nd Army Roja |

Fronts:

- Northern Front: 250 km., from East Prussia, along the Vistula River, to Modlin:

- 5th Army

- 1st Army – Warsaw

- 2nd Army – Warsaw

- Central Front:

- 4th Army – between Dęblin and Kock

- 3rd Army – between south of Kock and Brody

- Southern Front – between Brody and the Dniester River

Soviet

| North-Western Front Tukhachevsky |

|---|

| 4th Army Shuvayev |

| 3rd Cavalry Corps Bzhishkyan |

| 15th Army Kork |

| 3rd Army Lazarevich |

| 16th Army Sollogub |

| 1st Cavalry Army Budyonny |

Battle plans

Polish

By the beginning of August, the Polish retreat had become more organized, as their supply lines were steadily shortened. At first, Józef Piłsudski wanted to stop the Soviets at the Bug River and the city of Brest-Litovsk, but the Soviet advance resulted in their forces breaching that line, making that plan obsolete.[7] On the night of August 5–6, Piłsudski, staying at the Belweder Palace in Warsaw, conceived a revised plan. In the first phase, it called for Polish forces to withdraw across the Vistula River and defend the bridgeheads at Warsaw and at the Wieprz River, a tributary of the Vistula southeast of Warsaw. A quarter of the available divisions would be concentrated to the south for a strategic counteroffensive. Next, Piłsudski's plan called for the 1st and 2nd Armies of General Józef Haller's Central Front (10½ divisions) to take a passive role, facing the Soviet main westward thrust and holding their entrenched positions, Warsaw's last line of defence, at all costs. At the same time, the 5th Army (5½ divisions) under General Władysław Sikorski, subordinate to Haller, would defend the northern area near the Modlin Fortress; when it became feasible they were to strike from behind Warsaw, thus cutting off Soviet forces attempting to envelop Warsaw from that direction, and break through the enemy front and fall upon the rear of the Soviet Northwestern Front. Additionally, five divisions of the 5th Army were to protect Warsaw from the north. General Franciszek Latinik's 1st Army would defend Warsaw itself, while General Bolesław Roja's 2nd Army was to hold the Vistula River line from Góra Kalwaria to Dęblin.[1][7]

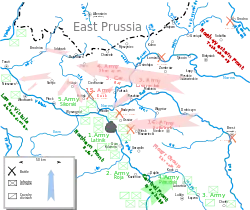

The crucial role, however, was assigned to the approximately 20,000-strong, newly formed Task Force (also translated as "Assault Group" or "Shock Army", from Polish Grupa Uderzeniowa), under the personal command of Piłsudski. This unit, composed of the most elite Polish units from the southern front, was to be reinforced by General Leonard Skierski's 4th Army and General Zygmunt Zieliński's 3rd Army. After retreating from the Bug River area, those armies had not moved directly toward Warsaw but had crossed the Wieprz River and broken off contact with their pursuers, thus confusing the enemy as to their whereabouts. The Assault Group's assignment was to spearhead a rapid offensive from their southern position in the Vistula-Wieprz River triangle. They were supposed to advance north, targeting a weak spot that the Polish intelligence thought to have found in between the Soviet Western and Southwestern Fronts, where their communications relied on the weak Mozyr Group. The aim of this operation was to throw the Soviet Western Front into chaos and separate it from its reserves. According to the plan, Sikorski's 5th Army and the advancing Assault Group would meet near the East Prussian border, leaving the Soviets trapped in an encirclement.[1]

Although based on fairly reliable information provided by Polish intelligence and intercepted Soviet radio communications,[9][10][11] the plan was called 'amateurish' by many high-ranking army officers and military experts, from Polish officers to the advisors from the French Military Mission to Poland who were quick to point out Piłsudski's lack of formal military education.

Criticism was levied on the logistical side, as suggested concentration points were as far as 100 to 150 miles (150 to 250 km) from many Polish units, most of them engaged on the front lines, and all of that a mere week before the planned date of the counterattack. All regrouping was within striking distance of the enemy; if Piłsudski and his staff mistimed when the Soviet offensive would begin, the Polish counter-attack and even the cohesion of the entire Polish front would be in chaos. Piłsudski himself admitted in his memoirs that it was a gamble; he decided to go forward with it due to politicians' defeatist stance, fear for the safety of the capital, and the prevailing feeling that if Warsaw were to fall, all would be lost. Only the desperate situation persuaded other army commanders to go along with it. They realized that under the circumstances, it was the only possible way to avoid a devastating defeat. The plan seemed so desperate and inept, that when the Soviets intercepted a copy of it, it was discarded as a poor deception attempt.[1]

The authorship of the plan is a matter of some controversy. Due to Piłsudski's political image, he was largely unpopular with the right wing of Polish politics.[1] Furthermore, Paderewski told top Allied leaders that Weygand had the idea; Paderewski knew better, but he was trying to use American support for a comeback in Polish politics.[12] After the battle, many reports suggested that the plan was in fact prepared either by the French general Maxime Weygand or by the Polish Chief of Staff Tadeusz Jordan-Rozwadowski.[1] According to recent research,[13] the French Military Mission proposed only a minor tactical counter-attack of two divisions towards Mińsk Mazowiecki. Its aim would have been to push the Red Army 30 kilometres back in order to ease subsequent ceasefire negotiations.[14] On the other hand, General Rozwadowski's plan called for a deeper thrust into Russian lines from the area of Wieprz. However, Piłsudski proposed a large-scale operation, with significant forces committed to beating the enemy forces rather than merely pushing them back. The plan was opposed by the French mission, which did not believe that the Polish army would be able to regroup after a 600 kilometre retreat.[15] Nonetheless, for many years, a myth persisted that it was the timely arrival of Allied forces that had saved Poland, a myth in which Weygand occupied the central role.

Davies points out Piłsudski "was left with only one serious possibility—a counter-offensive to the right of centre, at a point where a strike-force could be assembled from both northern and southern fronts. He pondered and checked these considerations during the night of 5–6 August, ruminating alone in his study at Belweder in Warsaw. In the morning, he received Rozwadowski and together they worked out the details. Rozwadowski pointed out the value of the River Wieprz ... by the evening, Order No. 8358/3 ... was ready and issued." Gen. Weygand admitted in his memoirs that "la victoire était polonaise, le plan polonais, l'armée polonaise." ("the victory was Polish, the plan Polish, the army Polish")[16]: 197–198, 222

Russian

Mikhail Tukhachevsky planned to encircle and surround Warsaw by crossing the Vistula River, near Włocławek, to the north and south of that city, northwest of Warsaw, and launch an attack from the northwest. With 24 divisions in four armies under his command, he planned to repeat the classic maneuver of Ivan Paskevich, who in 1831, during the November Uprising, had crossed the Vistula at Toruń and reached Warsaw practically unopposed, crushing the Polish uprising.[7][17] This move would also cut the Polish forces off from Gdańsk, the only port open to shipments of arms and supplies.[1]

The main weakness of the Russian plan was the poorly defended southern flank, secured only by the Pinsk Marshes and the weak Mazyr (Mozyrska) Group. That unit consisted of the 57th Infantry Division, 8,000 strong, and acted as the link between the Soviet two fronts (the majority of the Russian Southwest Front was engaged in the Battle of Lwów).[7]

Davies argues that the Soviet failure was caused by its tardiness in moving forces in for a frontal attack on Warsaw. By contrast the Poles were speedy, making every day's delay a liability to the Soviets. Furthermore, there was poor coordination between the Soviet Western Command and the three armies of the Southwestern Command. In the political sphere, Davies argues, there was too much friction inside the Soviet Command.[18] According to the historian Thomas Fiddick, rumors of disobedience to orders on the Soviet side by General Semyon Budyonny, or possibly even Joseph Stalin, were baseless. Moscow had decided for political reasons to reinforce the Crimean front at the expense of the Polish front. It meant it was replacing its goals of Europe-wide Communist revolution with a sort of "peaceful coexistence" with the West amidst internal consolidation.[19]

Battle

First phase

While the Red Army pushed forward, Gayk Bzhishkyan's Cavalry Corps, together with the 4th Army, crossed the Wkra River and advanced towards the town of Włocławek, the 15th and 3rd Armies were approaching Modlin Fortress and the 16th Army moved towards Warsaw. The final Russian assault on Warsaw began on August 12.[20] The Soviet 16th Army commenced the attack at the town of Radzymin (only 23 kilometres east of the city) and captured it the following day.[20] This initial success of the Red Army prompted Piłsudski to move up his plans by 24 hours.

The first phase of the battle started on August 12, with a Red Army frontal assault on the Praga bridgehead. In heavy fighting, Radzymin changed hands several times and most foreign diplomats left Warsaw; only the British and Vatican ambassadors chose to remain.[7] On August 14, Radzymin fell to the Red Army, and the lines of Władysław Sikorski's Polish 5th Army were broken. The 5th Army had to fight three Soviet armies at once: the 3rd, 4th, and 15th. The Modlin sector was reinforced with reserves (the Siberian Brigade and General Franciszek Krajowski's fresh 18th Infantry Division, both elite, battle-tested units: the 5th Army held out until dawn.

The situation was saved around midnight when the 203rd Uhlan Regiment managed to break through the Red Army lines and attack a Soviet command post, which resulted in a destruction of a radio station of A.D. Shuvayev's Soviet 4th Army.[1][20] The latter unit had only one radio station left, fixed on one frequency which was known to the Polish intelligence. Since the Polish code-breakers did not want the Russians to find out that their codes had been broken, the remaining Soviet radio station was neutralized by having the radio station in Warsaw recite the Book of Genesis in Polish and Latin on the frequency used by the 4th Army. It thus lost contact with its headquarters and continued marching toward Toruń and Płock, unaware of Tukhachevsky's order to turn south.[1] The raid by the 203rd Uhlans is sometimes referred to as "the Miracle of Ciechanów."[1]

At the same time, the Polish 1st Army under General Franciszek Latinik resisted a direct Red Army assault on Warsaw by six rifle divisions. The struggle for control of Radzymin forced Józef Haller, commander of the Polish Northern Front, to start the 5th Army's counterattack earlier than planned.[7]

During this time, Piłsudski was finishing his plans for the counter-offensive. He decided to supervise the attack, personally handing in a letter of resignation from all state functions so he could concentrate on the military situation and so that if he died, it would not paralyze the state.[7] He succeeded in raising the morale of the troops, between August 12 and August 15, visiting units of the 4th Army concentrating near Puławy, about 100 kilometres south of Warsaw.[7]

At that time, Piłsudski also commented on the dreadful state of logistics of the Polish army: "In the 21st Division, almost half of the soldiers paraded in front of me barefoot." The newly created Polish army had little choice in its equipment; its rifles and artillery pieces were produced in at least six countries, each of them using different ammunition.[7]

Second phase

The 27th Infantry Division of the Red Army managed to reach the village of Izabelin, 13 kilometres northwest of the capital, but this was the closest that Russian forces would come.[7]

Tukhachevsky, certain that all was going according to plan, was actually falling into Piłsudski's trap. There were only token Polish resistance in the path of the main Russian advance north and across the Vistula, on the right flank of the battle (from the perspective of the Soviet advance).[7] At the same time, south of Warsaw, on the battle's left front, the vital link between the Northwestern and Southwestern Fronts was much more vulnerable, protected only by a small Soviet force, the Mozyr Group.[7][20] Further, Semyon Budyonny, commanding the 1st Cavalry Army, a unit much feared by Piłsudski and other Polish commanders, disobeyed orders by the Soviet High Command, which at Tukhachevsky's insistence, ordered him to advance at Warsaw from the south. Budyonny resented this order, influenced by a grudge between commanding South-Western Front generals Alexander Ilyich Yegorov and Tukhachevsky.[7] In addition, the political games of Joseph Stalin, at the time the chief political commissar of the South-Western Front, further contributed to Yegorov's and Budyonny's disobedience.[7][20][21] Stalin, looking for personal glory, aimed to capture the besieged Lwów (Lviv), an important industrial center. Ultimately, Budyonny's forces marched on Lwów instead of Warsaw, and thus missed the battle.[20]

The Polish 5th Army counterattacked on August 14, crossing the Wkra River. It faced the combined forces of the Soviet 3rd and 15th Armies (both numerically and technically superior).[20] The struggle at Nasielsk lasted until August 15 and resulted in near-complete destruction of the town. However, the Soviet advance toward Warsaw and Modlin was halted at the end of August 15, and on that day Polish forces recaptured Radzymin, which boosted the Polish morale.[22]

From that moment on, Sikorski's 5th Army pushed exhausted Soviet units away from Warsaw, in an almost Blitzkrieg-like operation. Sikorski's units were given the support of almost all of the small number of mechanized units—tanks and armoured cars—that the Polish army had, as well as that of the two Polish armoured trains. It was able to advance rapidly at the speed of 30 kilometres a day, disrupting the Soviet "enveloping" northern manoeuvre.[1]

Third phase

On August 16, the Polish Assault Group commanded by Piłsudski began its march north from the Wieprz River. It faced the Mazyr Group, a Soviet corps that had defeated the Poles during the Kiev operation several months earlier. However, during its pursuit of the retreating Polish armies, the Mazyr Group had lost most of its troops and had been reduced to only one or two divisions covering a 150-kilometre front line on the left flank of the Soviet 16th Army. On the first day of the counteroffensive, only one of the five Polish divisions reported any sort of opposition, while the remaining four, supported by a cavalry brigade, managed to advance north 45 kilometres unopposed. When evening fell, the town of Włodawa had been liberated, and the communication and supply lines of the Soviet 16th Army had been cut. Even Piłsudski was surprised by the extent of these early successes. The Assault Group units covered about 70 kilometres in 36 hours. As planned, it split the Soviet fronts, disrupting the offensive, all without encountering any significant resistance. The Mazyr Group had already been defeated on the first day of the Polish counterattack. Consequently, the Polish armies found what they had hoped for—a large opening between the Soviet fronts. They exploited it ruthlessly, continuing their northward offensive with two armies following and falling on the surprised and confused enemy.[1][7][22]

On August 18, Tukhachevsky, in his headquarters in Minsk, some 300 miles (500 km) east of Warsaw, realized the extent of his defeat, quickly issuing the orders for the Red Army to retreat and regroup. He wanted to straighten the front line to improve his logistics, regain the initiative and push the Poles back again, but the situation had progressed beyond salvaging. His orders either arrived too late or failed to arrive at all. Soviet General Bzhishkyan's 3rd Cavalry Corps continued to advance toward Pomerania, its lines endangered by the Polish 5th Army, which had finally managed to push back the Red Army and switched over to pursuit. The Polish 1st Legions Infantry Division, in order to cut the enemy's retreat, carried out a forced march, going on the move for up to 21 hours a day, from Lubartów to Białystok—covering 163 miles (262 km) in only six days.[7] Throughout that period, the division engaged the enemy twice. The division's rapid advance allowed it to intercept the 16th Soviet Army, cutting it off from reinforcements near Białystok and forcing most of its troops to surrender.[7]

The Soviet armies in the centre of the front fell into chaos. Some divisions continued to fight their way toward Warsaw, while others retreated, lost their cohesion and panicked.[23] Tukhachevsky lost contact with most of his forces, and the Soviet plans were thrown into disorder. Only the 15th Army remained an organized force; it tried to obey Tukhachevsky's orders, shielding the withdrawal of the westernmost extended 4th Army. However, it was defeated twice on August 19 and 20 and joined the general rout of the Red Army's North-Western Front. Tukhachevsky had no choice but to order a full retreat toward the Western Bug River. By August 21, all organized resistance ceased to exist, and by August 31, the Soviet Southwestern Front was completely routed.[7][22]

Aftermath

Although Poland managed to achieve victory and push back the Russians, Piłsudski's plan to outmanoeuvre and surround the Red Army did not succeed completely. On July 4, four Soviet armies of the North-Western Front began to advance on Warsaw. After initial successes, by the end of August, three of them—the 4th, 15th and 16th Armies, as well as the bulk of Bzhishkyan's 3rd Cavalry Corps—had all but disintegrated, their remnants either taken prisoner or briefly interned after crossing the border into German East Prussia. The 3rd Army was the least affected; due to the speed of its retreat, the pursuing Polish troops could not catch up with it.[7]

Red Army losses were about 15,000 dead, 500 missing, 10,000 wounded and 65,000 captured, compared to Polish losses of approximately 4,500 killed, 22,000 wounded and 10,000 missing. Between 25,000 and 30,000 Soviet troops managed to reach the borders of Germany. After crossing into East Prussian territory, they were briefly interned, then allowed to leave with their arms and equipment. Poland captured about 231 pieces of artillery and 1,023 machine guns.[7]

The southern arm of the Red Army's forces had been routed and no longer posed a threat to the Poles. Semyon Budyonny's 1st Cavalry Army, besieging Lwów, had been defeated at the Battle of Komarów on August 31 and the Battle of Hrubieszów. By mid-October, the Polish army had reached the Tarnopol-Dubno-Minsk-Drisa line.

Tukhachevsky succeeded eventually in reorganizing his eastward-retreating forces, but not in regaining the initiative. In September, he established a new defensive line near Grodno. In order to break it, the Polish army fought the Battle of the Niemen River (September 15–21), once again defeating the Red Army. After the Battle of the Szczara River, both sides were exhausted. On October 12, under heavy pressure from France and Britain, a ceasefire was signed. By October 18, the fighting was over, and on March 18, 1921, the Treaty of Riga was signed, ending hostilities.

Bolshevik propaganda before the Battle of Warsaw had described the fall of Poland's capital as imminent, and its anticipated fall was to be a signal for the start of large-scale communist revolutions in Poland, Germany, and other European countries, economically devastated by the First World War. Due to the Polish victory, however, the Soviet attempts to overthrow the government of Lithuania (planned for August) had to be cancelled.[24] The Soviet defeat was therefore considered a setback for Soviet leaders supportive of that plan (particularly Vladimir Lenin).

A National Democrat Sejm deputy, Stanisław Stroński, coined the phrase, "Miracle at the Vistula" (Polish: "Cud nad Wisłą"), to underline his disapproval of Piłsudski's earlier "Ukrainian adventure."[25] In response, Poland's Prime Minister Wincenty Witos commented, "Whatever you want to write and say – whoever you want to dress in laurels and merits – this is 1920's 'Miracle at the Vistula.'"[1] Diaries from many participants of the battle attribute the outcome to the Blessed Virgin Mary citing multiple reasons, including widespread national prayer beforehand and subsequent reports of her appearance on the battlefield. The date of the turn of the battle is believed to coincide with the Solemnity of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary as celebrated by Roman Catholics.[26]

Breaking of Russian ciphers

According to documents found in 2005 at Poland's Central Military Archives, Polish cryptologists broke Russian ciphers they had intercepted as early as September 1919. At least some of the Polish victories, not only the Battle of Warsaw but also other battles, can be attributed to this. Lieutenant Jan Kowalewski, credited with the original breakthrough, received the Order of Virtuti Militari in 1921.[9][10][11][27]

See also

- Blue Army

- Siege of Warsaw (1939)

- Stefan Mazurkiewicz

- Battle of Warsaw 1920, a 2011 film by Jerzy Hoffman

Notes and references

- Szczepański, Janusz. "Kontrowersje Wokół Bitwy Warszanskiej 1920 Roku". Mówią Wieki (in Polish). Archived from the original (Controversies surrounding the Battle of Warsaw in 1920) on 14 May 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- Soviet casualties refer to all the operations during the battle, from the fighting on the approaches to Warsaw, through the counteroffensive, to the battles of Białystok and Osowiec, while the estimate of Red Army strength may be only for the units that were close to Warsaw, not counting the units held in reserve that took part in the later battles.

- Sketches from a Secret War by Timothy Snyder, Yale University Press, 2007, p. 11

- David Parker, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, W.W. Norton & Company, 2001, ISBN 0-393-02025-8, Google Print, p. 194

- Davies, Norman, White Eagle, Red Star: The Polish–Soviet War, 1919–20, (St. Martin's Press, 1972.) p. 29

- Jerzy Lukowski, Hubert Zawadzki, A Concise History of Poland, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-55917-0, Google Print, p.203

- Witold Lawrynowicz, Battle Of Warsaw 1920; A detailed write-up, with bibliography Archived 2012-01-18 at the Wayback Machine. Last accessed on November 5, 2006.

- Isaac Babel (2002). 1920 Diary. Yale University Press. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-0-300-09313-1.

- (in Polish) Ścieżyński, Mieczysław, Colonel of the (Polish) General Staff, Radjotelegrafja jako źrodło wiadomości o nieprzyjacielu (Radiotelegraphy as a Source of Intelligence on the Enemy), Przemyśl, Printing and Binding Establishment of (Military) Corps District No. X HQ, 1928, 49 pp.

- (in Polish) Paweł Wroński, "Sensacyjne odkrycie: Nie było cudu nad Wisłą" ("A Remarkable Discovery: There Was No Miracle at the Vistula"), Gazeta Wyborcza, online.

- Jan Bury, "Polish Codebreaking during the Russo-Polish War of 1919–1920," Cryptologia (2004) 28#3 pp. 193–203 online

- Biskupski 1987

- Janusz Odziemkowski (2005). ""Wojna Polski z Rosją Sowiecką, 1919–1920" ("Poland's War with Soviet Russia, 1919–1920")". Mówią Wieki (in Polish). 2/2005: 46–58.

- Piotr S. Wandycz (January 1960). "General Weygand and the Battle of Warsaw of 1920". Journal of Central European Affairs. XIX (IV): 357–365.

- Zdzisław Musialik (1987). General Weygand and the Battle of the Vistula, 1920. London: Piłsudski Institute. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-948019-03-6.

- Davies, N., 1972, White Eagle, Red Star, London: Macdonald & Co, ISBN 978-0-7126-0694-3

- John Erickson (2001). "Before the Gates of Warsaw: 1920". The Soviet High Command: A Military-Political History, 1918–1941. Frank Cass. pp. 84–90. ISBN 978-0-7146-5178-1.

- Norman Davies, "The Soviet Command and the Battle of Warsaw," Soviet Studies (1972) 23#4 pp. 573–585

- Thomas Fiddick, "The 'Miracle of the Vistula': Soviet Policy versus Red Army Strategy," Journal of Modern History (1973) 45#4 pp. 626–643 in JSTOR

- Robin D. S. Higham, Frederick W. Kagan, The military history of the Soviet Union, Palgrave Macmillan, 2002 ISBN 0-312-29398-4, Google Print, p. 44

- Stalin: The Man and His Era, Beacon Press, 1987, ISBN 0-8070-7005-X, Google Print, p. 189

- (in Polish) Wojna polsko-bolszewicka Archived 2013-11-11 at the Wayback Machine. Entry at Internetowa encyklopedia PWN. Last accessed on October 27, 2006.

- Janusz Cisek (2002). Kosciuszko, We Are Here!: American Pilots of the Kosciuszko Squadron in Defense of Poland, 1919–1921. McFarland & Company. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-7864-1240-2.

- Lesčius, Vytautas (2004). Lietuvos kariuomenė nepriklausomybės kovose 1918–1920 (PDF). Vilnius: General Jonas Žemaitis Military Academy of Lithuania. p. 296. ISBN 978-9955-423-23-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

- Frątczak, Sławomir Z. (2005). "Cud nad Wisłą". Głos (in Polish) (32/2005). Archived from the original on July 8, 2007. Retrieved June 18, 2006.

- Suski, Paul. "The Miracle on the Vistula – Rediscovered". Catholic Journal : Reflections on Faith and Culture. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- "Polish military cryptographers had broken Red Army radio codes so that Piłsudski knew the location of Soviet units in August 1920. Furthermore, Polish military radio-telegraphers sometimes blocked Tukhachevsky's orders to his troops by reading Bible excerpts on the same wavelength as that used by the Soviet commander." – Anna M. Cienciala, Natalia S. Lebedeva, Wojciech Materski. Katyn: A Crime Without Punishment. Yale University Press. 2008. p. 11.

Further reading

- Biskupski M. B. "Paderewski, Polish Politics, and the Battle of Warsaw, 1920," Slavic Review (1987) 46#3 pp. 503–512 he was trying to get American support for his comeback in Polish politics in JSTOR

- Edgar Vincent D'Abernon, The Eighteenth Decisive Battle of the World: Warsaw, 1920, Hyperion Press, 1977, ISBN 0-88355-429-1.

- Davies, Norman. White Eagle, Red Star: the Polish–Soviet War, 1919–20, Pimlico, 2003, ISBN 0-7126-0694-7.

- Davies, Norman. "The Soviet Command and the Battle of Warsaw," Soviet Studies (1972) 23#4 pp. 573–585 says the Soviet failure of command was responsible for its defeat

- Fiddick, Thomas. "The 'Miracle of the Vistula': Soviet Policy versus Red Army Strategy," Journal of Modern History (1973) 45#4 pp. 626–643 in JSTOR

- Fuller, J.F.C. The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Hunter Publishing, ISBN 0-586-08036-8.

- Hetherington, Peter. Unvanquished: Joseph Pilsudski, Resurrected Poland, and the Struggle for Eastern Europe (2012) pp. 425–458 excerpt and text search

- Watt, Richard M. Bitter Glory: Poland and Its Fate, 1918–1939, Hippocrene Books, 1998, ISBN 0-7818-0673-9.

- Zamoyski, Adam. Warsaw 1920: Lenin's Failed Conquest of Europe (2008) excerpt and text search

In Polish

- M. Tarczyński, Cud nad Wisłą, Warszawa, 1990.

- Józef Piłsudski, Pisma zbiorowe, Warszawa, 1937, reprinted by Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza, 1991, ISBN 83-03-03059-0.

- Mikhail Tukhachevski, Lectures at Military Academy in Moscow, February 7–10, 1923, reprinted in Pochód za Wisłę (March across the Vistula), Łódź, 1989.

External links

- Robert Szymczak, Polish–Soviet War: Battle of Warsaw, Historynet

- 3 scans Polish maps

- (in Polish) "Bolszewik złamany Gazeta Wyborcza article about breaking of Soviet ciphers.