Brownsea Island Scout camp

The Brownsea Island Scout camp was the site of a boys' camping event on Brownsea Island in Poole Harbour, southern England, organised by Lieutenant-General Baden-Powell to test his ideas for the book Scouting for Boys. Boys from different social backgrounds participated from 1 to 8 August 1907 in activities around camping, observation, woodcraft, chivalry, lifesaving and patriotism. The event is regarded as the origin of the worldwide Scout movement.

| Brownsea Island Scout camp | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

Robert Baden-Powell with future Scouts on Brownsea Island | |||

| Owner | National Trust | ||

| Location | Poole Harbour | ||

| Country | England | ||

| Coordinates | 50°41′18″N 1°58′45″W | ||

| Founded | 1 August 1907 | ||

| Founder | Robert Baden-Powell | ||

|

| |||

Up to the early 1930s, Boy Scouts continued to camp on Brownsea Island. In 1963, a formal 50-acre (20 ha) Scout campsite was opened by Olave Baden-Powell when the island became a nature conservation area owned by the National Trust. In 1973, a Scout Jamboree with six hundred Scouts was held on the island.

The worldwide centenary of Scouting took place at the Brownsea Island Scout camp, celebrated on 1 August 2007, the 100th anniversary of the start of the first encampment. Activities by The Scout Association at the campsite included four Scout camps and a Sunrise Ceremony.

Background

Robert Baden-Powell had become a national hero during the Boer War as a result of his successful defence of Mafeking, which was under siege from October 1899 to May 1900.[1] The Mafeking Cadets, made up of local boys aged 12 to 15, acted as messengers throughout the siege, and had impressed him with their resourcefulness and courage. Baden-Powell had also published popular books on military scouting, including Aids to Scouting for NCOs and Men, published in 1899. Though written for non-commissioned officers, the book became a best-seller and was used by teachers and youth organisations. In the years after the war Baden-Powell broached the idea of a new youth organisation with William Alexander Smith, founder of the Boys' Brigade, with whom he discussed setting up a Boys Brigade Scouting achievement. To test his ideas while writing Scouting for Boys, Baden-Powell conceived of an experimental camp, creating a programme to take place on Brownsea Island during 1907.[2] He invited his friend, Major Kenneth McLaren, to attend the camp as an assistant.[3][4]

First Scout encampment

Site and camp organisation

Baden-Powell had visited Brownsea Island as a boy with his brothers. It covers 560 acres (2.3 km2) of woodland and open areas, and features two lakes. The island perfectly suited his needs for the camp as it was isolated from the mainland and hence from the press, yet was only a short ferry trip from Poole, making for easy logistics.[5]

Baden-Powell invited boys from different social backgrounds to the camp, a revolutionary idea during the class-conscious Edwardian era.[6] Eleven came from the well-to-do private boarding schools of Eton and Harrow, mostly sons of Baden-Powell's friends. Seven came from the Boys' Brigade at Bournemouth, and three came from the Brigade at Poole & Hamworthy. Baden-Powell's nine-year-old nephew Donald Baden-Powell also attended.[7] The camp fee was dependent on means: one pound (equivalent to £103.91 in 2018) for the public school boys, and three shillings and sixpence (£0.18 in decimal currency; equivalent to £18.70 in 2018) for the others.[8]

The boys were arranged into four patrols, designated as the Wolves, Ravens, Bulls and Curlews.[8] It is uncertain if 20 or 21 boys attended the camp. At least four authors list attendance at 20 boys, and that they were organized into five patrols with Baden-Powell's nephew Donald as camp orderly. These sources included an article in The Scout (1908), Sir Percy Everett in The First Ten Years (1948) and Rover Word (1936), and E. E. Reynolds in The Scout Movement (1950). In 1964, William Hillcourt added the fourth Rodney brother, Simon, in Two Lives of a Hero, bringing the total to 21. This evidence was supported by the oldest Rodney brother, then the 8th Baron Rodney. The reasons why Simon Rodney was not listed by the other authors is not clear, but evidence that he was present and the 6th member of the Curlews Patrol, was recounted by Scouting historian Colin Walker.[9]

The boys did not have uniform shirts, but wore khaki scarves and were presented with brass fleur-de-lis badges, the first use of the Scout emblem. They also wore a coloured knot on their shoulder indicating their patrol: green for Bulls, blue for Wolves, yellow for Curlews, and red for Ravens. The patrol leader carried a staff with a flag depicting the patrol animal. After passing tests on knots, tracking, and the national flag, they were given another brass badge, a scroll with the words Be Prepared, to wear below the fleur-de-lis.[10]

Programme

Each patrol camped in an army bell tent.[6] The camp began each day with a blast from a kudu horn that Baden-Powell had found in the Somabula forest during the Matabele campaign of 1896. He used the same kudu horn to open the Coming of Age Jamboree 22 years later in 1929.[11] The day began at 6:00 am, with cocoa, exercises, flag break and prayers, followed by breakfast at 8:00 am. Then followed the morning exercise of the subject of the day, as well as bathing, if deemed necessary.[6] After lunch there was a strict siesta (no talking allowed), followed by the afternoon activity based on the subject of the day. At 5:00 p.m. the day ended with games, supper, campfire yarns and prayers.[10][11] Baden-Powell made full use of his personal fame as the hero of the siege of Mafeking. For many of the participants, the highlights of the camp were his campfire yarns of his African experiences, and the Zulu "Ingonyama" chant, translating to "he is a lion".[11] Turning in for the night was compulsory for every patrol at 9:00 pm, regardless of age.[6]

Each day was based on a different theme: Day 1 was preliminary, day 2 was campaigning, day 3 was observation, day 4 for woodcraft, day 5 was chivalry, day 6 was saving a life, day 7 was patriotism, and day 8 was the conclusion.[3][11] The participants left by ferry on the 9th day, 9 August 1907.[12] The camp cost £55 two shillings, and eight pence; after the boys' fees, and donations totaling £16, this left a deficit of just over £24. The deficit was cleared by Saxton Noble, whose two sons Marc and Humphrey had attended.[3][6] Baden-Powell considered the camp successful.[12]

Legacy and commemoration

Following the successful camp, Baden-Powell went on an extensive speaking tour arranged by his publisher, Pearsons, to promote his forthcoming Scouting for Boys, which officially began the Scout movement.[9] It initially appeared as six fortnightly installments, beginning in January 1908, and later appeared in book form. Scouting began to spread throughout Great Britain and Ireland, then through the countries of the British Empire, and soon to the rest of the world.[10][11] A reunion of the original campers was held in 1928 at the Chief Scout's home at Pax Hill in Hampshire.[6]

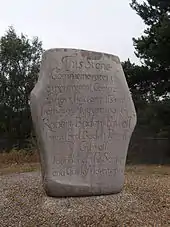

A commemorative stone by sculptor Don Potter was unveiled on 1 August 1967 by Betty Clay née Baden-Powell, younger daughter of Lord and Lady Baden-Powell. It is located near the encampment area.[14]

In May 2000, twenty trees were planted, one for each boy who had attended the first camp. During the planting ceremony, the Scout Chief Commissioner for England, along with representatives of the Scouts and the Guides, planted the trees on the seaward side of the original site. The trees were designed to act as a memorial to the camp, as well as providing a series of future windbreaks against coastal winds.[6]

Campsite history

From 1927 to 2000

After the death of owner Charles van Raalte in 1907, his wife Florence stayed on Brownsea until 1925. Mary Bonham-Christie bought the island at an auction in 1927. In 1932, Bonham-Christie allowed 500 Scouts to camp there to celebrate the Silver Jubilee of Scouting, but shortly afterwards she closed the island to the public and it became very overgrown. In 1934, some Sea Scouts were camping on the island when a fire broke out. Bonham-Christie blamed the Sea Scouts, although the fire did not start where they were camping. The fire engulfed most of the island, burning west to east. The eastern buildings were saved only by a change in wind direction. Although it was not known how the fire started, Scouts were not allowed to camp on the island again until after Bonham-Christie's death in 1961.[15] Her family became liable for death duties on her estate so the island was put up for sale. Interested citizens who feared that the island would be bought by developers helped raise an endowment, and in 1962 the government allowed the National Trust to take over management of the island in lieu of the death duties.[16][17]

The island was reopened to the public in 1963 by Lady Baden-Powell when it came under the control of the National Trust. She planted a mulberry tree to mark the occasion. The Trust has continuously maintained the island since then as a conservation area.[16][17] In 1964, 50 acres (20 ha) near the original campsite were set aside for Scout and Guide camping.The 1st and 9th Seaford Scouts camped near the site claiming to be the first to do so since BP.[18] In 1967 the Scout Association held a Patrol Leaders Camp on the island for the Diamond Jubilee of Scouting from 29 to 5 July August.[19] In 1973, a jamboree was held on the island for 600 Scouts from seven nations, along with one of the original campers, then aged 81.[6]

After 2000

From 2000, The National Trust maintains the Scout and Guide campsite, South Shore Lodge and the Baden-Powell Outdoor Centre where members of Brownsea Island Scout Fellowship and Friends of Guiding operate a small trading post.[20]

The Baden-Powell Outdoor Centre was opened on 14 September 2007 and includes a new camp reception and new washroom facilities. The centre also hosts a small Scouting museum.[6] The campsite is compartmentalised, with the memorial stone, shop, flags, and destination signs in one area on the south-west corner of the island. Radiating off from this centre are many small camp zones, about a dozen acres each, surrounded by trees and fences. The area set aside for camping now covers 50 acres (20 ha); there is room for up to four hundred campers on the site.[6]

St. Mary's Church, located on the island about 0.2 miles (0.3 km) from the camp, posts Scout and Guide flags at the approach to the altar. In 2007, to coincide with the Scouting centenary, about 40 new kneelers or hassocks were given to the church, decorated with the 21 World Scout Jamboree badges and other Scouting, Guiding and island badges.[21] The church is often used for services during large camps.

Brownsea Island is generally open to the public from March to October, via ferry from Poole.[22] The island was reserved for Scouts and Scouters on 1 August 2007 during the Sunrise Camp.[23] The National Trust operates events throughout the summer months including guided tours, trails, and activities in the visitor centre.

A statue of Baden-Powell, created in 2008 by sculptor David Annand to commemorate the camp, is situated in Poole and faces Brownsea Island.[24][25]

Centenary of Scouting

Since March 2006, travel packages have been available for Scouts to camp on the island, and Scout and Guide groups can also book day activities. To celebrate one hundred years of Scouting, four camps were organised on the island by The Scout Association during July and August 2007.[23][26][27] The Patrol Leaders Camp, which ran from 26 until 28 July 2007, involved Scouts from the United Kingdom engaging in activities such as sea kayaking.[26] The Replica Camp was a living history recreation of the original 1907 camp on Brownsea Island, which ran from 28 July to 3 August 2007, parallel to the other camps.[26][28] The Sunrise Camp (29 July to 1 August 2007) hosted over 300 Scouts from nearly every country in the world. The young people travelled from the 21st World Scout Jamboree in Hylands Park, Essex, to Brownsea Island on 1 August 2007 for the Sunrise Ceremony.[26] At 8:00 am, Scouts all over the world renewed their Scout promise.[29] The Chief Scout of the United Kingdom, Peter Duncan, blew the original kudu horn. One Scout from each Scouting country passed over a "Bridge of Friendship"; Scouts shook the left hand of each Scout as they passed one another. The New Centenary Camp (1–4 August 2007) hosted Scouts from the United Kingdom and abroad.[26]

See also

- Scout Adventures – network of activity centres owned and managed by The Scout Association

- Humshaugh – site of the first official Scout camp, held in August 1908

References

- "The Siege of Mafeking". British Battles.com. Retrieved 7 July 2006.

- Boehmer, Elleke (2004). "Notes to 2004 edition". Scouting for Boys. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280547-9.

- Walker, Johnny. "Brownsea and its significance – The world's first Scout Camp". Scout and Guide Historical Society. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- Jeal, Tim (1989). Baden-Powell. London: Hutchinson. p. 385. ISBN 0-09-170670-X.

- "Brownsea Island Ferries, Poole Quay". Brownsea Island Ferries Ltd. 2007. Retrieved 10 June 2007.

- Woolgar, Brian; La Riviere, Sheila (2002). Why Brownsea? The Beginnings of Scouting. Brownsea Island Scout and Guide Management Committee (re-issue 2007, Wimborne Minster: Minster Press).

- "B.-P.'s Experimental camp on Brownsea Island" (PDF). The Scout Association. 1999. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 July 2007. Retrieved 11 June 2007.

- Beardsall, Jonny (Spring 2007). "Dib, dib, dib ... One hundred years of Scouts at Brownsea". National Trust Magazine. pp. 52–55.

- Walker, Colin (2007). Brownsea: B-P's Acorn, The World's First Scout Camp. Write Books. ISBN 978-1-905546-21-3.

- "Brownsea Island". Scouting Through History. US Scouting Service Project. 1947. Retrieved 10 June 2007.

- "The First Camp". thescoutingpages.org. Archived from the original on 7 February 2007. Retrieved 11 June 2007.

- Baden-Powell, Robert (1908). Scouting for Boys, part VI. Notes for instructors. London: Pearson. pp. 343–346.

- "Betty Clay 1964–1984". Spanglefish.com. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- Walker, Johnny. "Potter, Donald Steele. 1902–2004". Scout Guide Historical Society. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- "Brownsea Island – History question". Scouts Archive. Retrieved 11 June 2007.

- "Isle of Purbeck – Brownsea Island". Isle of Purbeck Trust. Archived from the original on 4 June 2007. Retrieved 11 June 2007.

- "A history of Brownsea Island". National Trust. Archived from the original on 16 July 2015. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- "Camping". Brownsea 2007. 2007. Archived from the original on 17 May 2007. Retrieved 10 June 2007.

- "Scout Association catalogue – GB 2253 TC" (pdf). National Archives. p. 19. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

TC/82 Brownsea Island: Diamond Jubilee National Patrol Leaders' Camp 1967

- "Brownsea Island Scout & Guide Camp". Brownsea Island Organisation. Retrieved 7 July 2006.

- Nigel, Lloyd (2004). St Marys Church, Brownsea Island Visitor Leaflet. Brownsea Island: St Mary's Church.

- "Opening times". National Trust. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- "Scout island focus of celebration". BBC News. 21 March 2007. Retrieved 9 June 2007.

- "Baden-Powell Returns To Poole Quay". Borough of Poole. 2008. Archived from the original on 16 February 2011.

- "Baden Powell Centenary Sculpture Project". Baden-Powell Centenary Sculpture. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "Events". Brownsea 2007. 2007. Archived from the original on 26 May 2007. Retrieved 10 June 2007.

- "Scouts in centenary celebrations". BBC. 1 August 2007. Retrieved 4 August 2007.

- Harper, Alison (1 August 2007). "From small camp to global phenomenon". BBC. Retrieved 4 August 2007.

- "Scouting's Sunrise". World Organization of the Scout Movement. 2007. Archived from the original on 14 August 2013. Retrieved 3 July 2013.