Celtic languages

The Celtic languages (usually /ˈkɛltɪk/, but sometimes /ˈsɛltɪk/) are a group of related languages descended from Proto-Celtic. They form a branch of the Indo-European language family.[1] The term "Celtic" was first used to describe this language group by Edward Lhuyd in 1707,[2] following Paul-Yves Pezron, who made the explicit link between the Celts described by classical writers and the Welsh and Breton languages.[3]

| Celtic | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Formerly widespread in much of Europe and central Anatolia; today Cornwall, Wales, Scotland, Ireland, Brittany, the Isle of Man, Chubut Province (Y Wladfa), and Nova Scotia |

| Linguistic classification | Indo-European

|

| Proto-language | Proto-Celtic |

| Subdivisions | |

| ISO 639-2 / 5 | cel |

| Linguasphere | 50= (phylozone) |

| Glottolog | celt1248 |

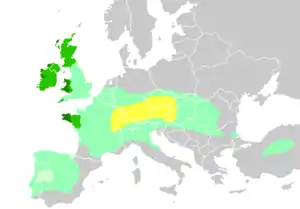

Distribution of Celtic speakers:

Hallstatt culture area, 6th century BC

Maximal Celtic expansion, c. 275 BC

Lusitanian area; Celtic affiliation unclear

Areas where Celtic languages were spoken in the Middle Ages

Areas where Celtic languages remain widely spoken today | |

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Celts and Modern Celts |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

During the 1st millennium BC, Celtic languages were spoken across much of Europe and central Anatolia. Today, they are restricted to the northwestern fringe of Europe and a few diaspora communities. There are six living languages: the four continuously living languages Breton, Irish, Scottish Gaelic and Welsh, and the two revived languages Cornish and Manx. All are minority languages in their respective countries, though there are continuing efforts at revitalisation. Welsh is an official language in Wales and Irish is an official language of Ireland and of the European Union. Welsh is the only Celtic language not classified as endangered by UNESCO. The Cornish and Manx languages went extinct in modern times. They have been the object of revivals and now each has several hundred second-language speakers.

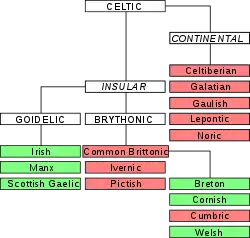

Irish, Manx and Scottish Gaelic form the Goidelic languages, while Welsh, Cornish and Breton are Brittonic. All of these are Insular Celtic languages, since Breton, the only living Celtic language spoken in continental Europe, is descended from the language of settlers from Britain. There are a number of extinct but attested continental Celtic languages, such as Celtiberian, Galatian and Gaulish. Beyond that there is no agreement on the subdivisions of the Celtic language family. They may be divided into P-Celtic and Q-Celtic.

The Celtic languages have a rich literary tradition. The earliest specimens of written Celtic are Lepontic inscriptions from the 6th century BC in the Alps. Early Continental inscriptions used Italic and Paleohispanic scripts. Between the 4th and 8th centuries, Irish and Pictish were occasionally written in an original script, Ogham, but Latin script came to be used for all Celtic languages. Welsh has had a continuous literary tradition from the 6th century AD.

Living languages

SIL Ethnologue lists six living Celtic languages, of which four have retained a substantial number of native speakers. These are the Goidelic languages (Irish and Scottish Gaelic, both descended from Middle Irish) and the Brittonic languages (Welsh and Breton, both descended from Common Brittonic).[4]

The other two, Cornish (Brittonic) and Manx (Goidelic), died out in modern times[5][6][7] with their presumed last native speakers in 1777 and 1974 respectively. For both these languages, however, revitalisation movements have led to the adoption of these languages by adults and children and produced some native speakers.[8][9]

Taken together, there were roughly one million native speakers of Celtic languages as of the 2000s.[10] In 2010, there were more than 1.4 million speakers of Celtic languages.[11]

Demographics

| Language | Native name | Grouping | Number of native speakers | Number of skilled speakers | Area of origin (still spoken) | Regulated by/language body | Estimated number of speakers in major cities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irish | Gaeilge / Gaedhilge / Gaelainn / Gaeilig / Gaeilic | Goidelic | 40,000–80,000[12][13][14][15] In the Republic of Ireland, 73,803 people use Irish daily outside the education system.[16] |

Total speakers: 1,887,437 Republic of Ireland: 1,774,437[17] United Kingdom: 95,000 United States: 18,000 |

Gaeltacht of Ireland | Foras na Gaeilge | Dublin: 184,140 Galway: 37,614 Cork: 57,318[18] Belfast: 14,086[19] |

| Welsh | Cymraeg / Y Gymraeg | Brittonic | 562,000 (19.0% of the population of Wales) claim that they "can speak Welsh" (2011)[20][21] | Total speakers: ≈ 947,700 (2011) Wales: 788,000 speakers (26.7% of the population)[20][21] England: 150,000[22] Chubut Province, Argentina: 5,000[23] United States: 2,500[24] Canada: 2,200[25] |

Wales | Welsh Language Commissioner The Welsh Government (previously the Welsh Language Board, Bwrdd yr Iaith Gymraeg) |

Cardiff: 54,504 Swansea: 45,085 Newport: 18,490[26] Bangor: 7,190 |

| Breton | Brezhoneg | Brittonic | 206,000 | 356,000[27] | Brittany | Ofis Publik ar Brezhoneg | Rennes: 7,000 Brest: 40,000 Nantes: 4,000[28] |

| Scottish Gaelic | Gàidhlig | Goidelic | 57,375 (2011)[29] | Scotland: 87,056 (2011)[29] Nova Scotia, Canada: 1,275 (2011)[30] | Scotland | Bòrd na Gàidhlig | Glasgow: 5,726 Edinburgh: 3,220[31] Aberdeen: 1,397[32] |

| Cornish | Kernowek / Kernewek | Brittonic | Unknown[33] | 2,000[34] | Cornwall | Akademi Kernewek Cornish Language Partnership (Keskowethyans an Taves Kernewek) |

Truro: 118[35] |

| Manx | Gaelg / Gailck | Goidelic | 100+,[8][36] including a small number of children who are new native speakers[37] | 1,823[38] | Isle of Man | Coonceil ny Gaelgey | Douglas: 507[39] |

Classification

Celtic is divided into various branches:

- Lepontic, the oldest attested Celtic language (from the 6th century BC).[42] Anciently spoken in Switzerland and in Northern-Central Italy. Coins with Lepontic inscriptions have been found in Noricum and Gallia Narbonensis.[43][44][45][46]

- Celtiberian, also called Eastern or Northeastern Hispano-Celtic, spoken in the ancient Iberian Peninsula, in the eastern part of Old Castile and south of Aragon. Modern provinces: Segovia, Burgos, Soria, Guadalajara, Cuenca, Zaragoza and Teruel. The relationship of Celtiberian with Gallaecian, in northwest Iberia, is uncertain.[47][48]

- Gallaecian, also known as Western or Northwestern Hispano-Celtic, anciently spoken in the northwest of the peninsula (modern Northern Portugal, Galicia, Asturias and Cantabria).[49]

- Gaulish languages, including Galatian and possibly Noric. These were once spoken in a wide arc from Belgium to Turkey. They are now all extinct.

- Brittonic, spoken in Great Britain and Brittany. Including the living languages Breton, Cornish, and Welsh, and the lost Cumbric and Pictish, though Pictish may be a sister language rather than a daughter of Common Brittonic.[50] Before the arrival of Scotti on the Isle of Man in the 9th century, there may have been a Brittonic language there. The theory of a Brittonic Ivernic language predating Goidelic speech in Ireland has been suggested, but is not widely accepted.[5]

- Goidelic, including the extant Irish, Manx, and Scottish Gaelic.

Continental/Insular Celtic and P/Q-Celtic hypotheses

Scholarly handling of Celtic languages has been contentious owing to scarceness of primary source data. Some scholars (such as Cowgill 1975; McCone 1991, 1992; and Schrijver 1995) distinguish Continental Celtic and Insular Celtic, arguing that the differences between the Goidelic and Brittonic languages arose after these split off from the Continental Celtic languages.[51] Other scholars (such as Schmidt 1988) distinguish between P-Celtic and Q-Celtic languages based on their preferential use of these respective consonants in similar words. Most of the Gallic and Brittonic languages are P-Celtic, while the Goidelic and Celtiberian languages are Q-Celtic. The P-Celtic languages (also called Gallo-Brittonic) are sometimes seen (for example by Koch 1992) as a central innovating area as opposed to the more conservative peripheral Q-Celtic languages.

The Breton language is Brittonic, not Gaulish, though there may be some input from the latter,[52] having been introduced from Southwestern regions of Britain in the post-Roman era and having evolved into Breton.

In the P/Q classification schema, the first language to split off from Proto-Celtic was Gaelic. It has characteristics that some scholars see as archaic, but others see as also being in the Brittonic languages (see Schmidt). In the Insular/Continental classification schema, the split of the former into Gaelic and Brittonic is seen as being late.

The distinction of Celtic into these four sub-families most likely occurred about 900 BC according to Gray and Atkinson[53][54] but, because of estimation uncertainty, it could be any time between 1200 and 800 BC. However, they only considered Gaelic and Brythonic. The controversial paper by Forster and Toth[55] included Gaulish and put the break-up much earlier at 3200 BC ± 1500 years. They support the Insular Celtic hypothesis. The early Celts were commonly associated with the archaeological Urnfield culture, the Hallstatt culture, and the La Tène culture, though the earlier assumption of association between language and culture is now considered to be less strong.[56][57]

There are legitimate scholarly arguments for both the Insular Celtic hypothesis and the P-/Q-Celtic hypothesis. Proponents of each schema dispute the accuracy and usefulness of the other's categories. However, since the 1970s the division into Insular and Continental Celtic has become the more widely held view (Cowgill 1975; McCone 1991, 1992; Schrijver 1995), but in the middle of the 1980s, the P-/Q-Celtic theory found new supporters (Lambert 1994), because of the inscription on the Larzac piece of lead (1983), the analysis of which reveals another common phonetical innovation -nm- > -nu (Gaelic ainm / Gaulish anuana, Old Welsh enuein "names"), that is less accidental than only one. The discovery of a third common innovation would allow the specialists to come to the conclusion of a Gallo-Brittonic dialect (Schmidt 1986; Fleuriot 1986).

The interpretation of this and further evidence is still quite contested, and the main argument for Insular Celtic is connected with the development of verbal morphology and the syntax in Irish and British Celtic, which Schumacher regards as convincing, while he considers the P-Celtic/Q-Celtic division unimportant and treats Gallo-Brittonic as an outdated theory.[42] Stifter affirms that the Gallo-Brittonic view is "out of favour" in the scholarly community as of 2008 and the Insular Celtic hypothesis "widely accepted".[58]

When referring only to the modern Celtic languages, since no Continental Celtic language has living descendants, "Q-Celtic" is equivalent to "Goidelic" and "P-Celtic" is equivalent to "Brittonic".

How the family tree of the Celtic languages is ordered depends on which hypothesis is used:

Eska (2010)

Eska[59] evaluates the evidence as supporting the following tree, based on shared innovations, though it is not always clear that the innovations are not areal features. It seems likely that Celtiberian split off before Cisalpine Celtic, but the evidence for this is not robust. On the other hand, the unity of Gaulish, Goidelic, and Brittonic is reasonably secure. Schumacher (2004, p. 86) had already cautiously considered this grouping to be likely genetic, based, among others, on the shared reformation of the sentence-initial, fully inflecting relative pronoun *i̯os, *i̯ā, *i̯od into an uninflected enclitic particle. Eska sees Cisalpine Gaulish as more akin to Lepontic than to Transalpine Gaulish.

- Celtic

- Celtiberian

- Gallaecian

- Nuclear Celtic?

- Cisalpine Celtic: Lepontic → Cisalpine Gaulish†

- Transalpine–Goidelic–Brittonic (secure)

- Transalpine Gaulish† ("Transalpine Celtic")

- Insular Celtic

Eska considers a division of Transalpine–Goidelic–Brittonic into Transalpine and Insular Celtic to be most probable because of the greater number of innovations in Insular Celtic than in P-Celtic, and because the Insular Celtic languages were probably not in great enough contact for those innovations to spread as part of a sprachbund. However, if they have another explanation (such as an SOV substratum language), then it is possible that P-Celtic is a valid clade, and the top branching would be:

- Transalpine–Goidelic–Brittonic (P-Celtic hypothesis)

- Goidelic

- Gallo-Brittonic

- Transalpine Gaulish ("Transalpine Celtic")

- Brittonic

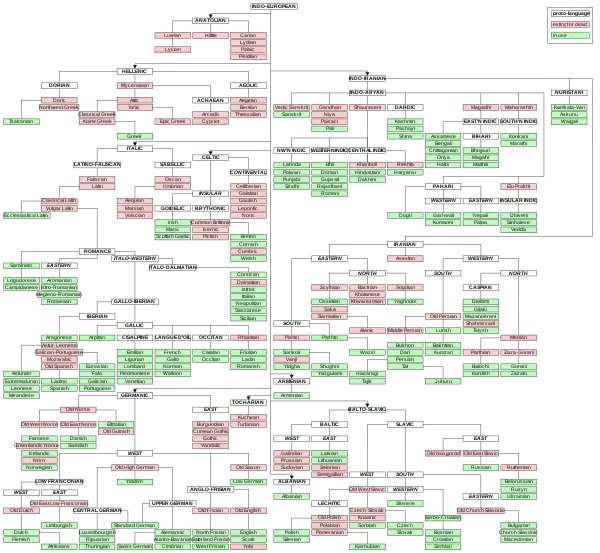

Italo-Celtic

Within the Indo-European family, the Celtic languages have sometimes been placed with the Italic languages in a common Italo-Celtic subfamily. This hypothesis fell somewhat out of favour after reexamination by American linguist Calvert Watkins in 1966.[60] Irrespective, some scholars such as Ringe, Warnow and Taylor have argued in favour of an Italo-Celtic grouping in 21st century theses.[61]

Characteristics

Although there are many differences between the individual Celtic languages, they do show many family resemblances.

- consonant mutations (Insular Celtic only)

- inflected prepositions (Insular Celtic only)

- two grammatical genders (modern Insular Celtic only; Old Irish and the Continental languages had three genders, although Gaulish may have merged the neuter and masculine in its later forms)[62]

- a vigesimal number system (counting by twenties)

- Cornish hwetek ha dew ugens "fifty-six" (literally "sixteen and two twenty")

- verb–subject–object (VSO) word order (probably Insular Celtic only)

- an interplay between the subjunctive, future, imperfect, and habitual, to the point that some tenses and moods have ousted others

- an impersonal or autonomous verb form serving as a passive or intransitive

- Welsh dysgaf "I teach" vs. dysgir "is taught, one teaches"

- Irish múinim "I teach" vs. múintear "is taught, one teaches"

- no infinitives, replaced by a quasi-nominal verb form called the verbal noun or verbnoun

- frequent use of vowel mutation as a morphological device, e.g. formation of plurals, verbal stems, etc.

- use of preverbal particles to signal either subordination or illocutionary force of the following clause

- mutation-distinguished subordinators/relativisers

- particles for negation, interrogation, and occasionally for affirmative declarations

- pronouns positioned between particles and verbs

- lack of simple verb for the imperfective "have" process, with possession conveyed by a composite structure, usually BE + preposition

- Cornish Yma kath dhymm "I have a cat", literally "there is a cat to me"

- Welsh Mae cath gyda fi "I have a cat", literally "a cat is with me"

- Irish Tá cat agam "I have a cat", literally "there is a cat at me"

- use of periphrastic constructions to express verbal tense, voice, or aspectual distinctions

- distinction by function of the two versions of BE verbs traditionally labelled substantive (or existential) and copula

- bifurcated demonstrative structure

- suffixed pronominal supplements, called confirming or supplementary pronouns

- use of singulars or special forms of counted nouns, and use of a singulative suffix to make singular forms from plurals, where older singulars have disappeared

Examples:

- Irish: Ná bac le mac an bhacaigh is ní bhacfaidh mac an bhacaigh leat.

- (Literal translation) Don't bother with son the beggar's and not will-bother son the beggar's with-you.

- bhacaigh is the genitive of bacach. The igh the result of affection; the bh is the lenited form of b.

- leat is the second person singular inflected form of the preposition le.

- The order is verb–subject–object (VSO) in the second half. Compare this to English or French (and possibly Continental Celtic) which are normally subject–verb–object in word order.

- Welsh: pedwar ar bymtheg a phedwar ugain

- (Literally) four on fifteen and four twenties

- bymtheg is a mutated form of pymtheg, which is pump ("five") plus deg ("ten"). Likewise, phedwar is a mutated form of pedwar.

- The multiples of ten are deg, ugain, deg ar hugain, deugain, hanner cant, trigain, deg a thrigain, pedwar ugain, deg a phedwar ugain, cant.

Comparison table

The lexical similarity between the different Celtic languages is apparent in their core vocabulary, especially in terms of actual pronunciation. Moreover, the phonetic differences between languages are often the product of regular sound change (i.e. lenition of /b/ into /v/ or Ø).

The table below has words in the modern languages that were inherited directly from Proto-Celtic, as well as a few old borrowings from Latin that made their way into all the daughter languages. There is often a closer match between Welsh, Breton, and Cornish on the one hand, and Irish, Scottish Gaelic and Manx on the other. For a fuller list of comparisons, see the Swadesh list for Celtic.

| English | Brittonic | Goidelic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Welsh | Breton[63] | Cornish | Irish[64] | Scottish Gaelic[65] | Manx | |

| bee | gwenynen | gwenanenn | gwenenen | beach | seillean | shellan |

| big | mawr | meur | meur | mór | mòr | mooar |

| dog | ci | ki | ki | madraarchaic cú | cù | coo |

| fish | pysgodyn† | pesk† | pysk† | iasc | iasg | eeast |

| full | llawn | leun | leun | lán | làn | lane |

| goat | gafr | gavr | gaver | gabhar | gobhar | goayr |

| house | tŷ | ti | chi | teach, tigh | taigh | thie |

| lip (anatomical) | gwefus | gweuz | gweus | liopa | bile | meill |

| mouth of a river | aber | aber | aber | inbhear | inbhir | inver |

| four | pedwar | pevar | peswar | ceathair | ceithir | kiare |

| night | nos | noz | nos | oíche | oidhche | oie |

| number† | rhif, nifer† | niver† | niver† | uimhir | àireamh | earroo |

| three | tri | tri | tri | trí | trì | tree |

| milk | llaeth† | laezh† | leth† | bainne | bainne | bainney |

| you (sg) | ti | te | ty | tú | thu | oo |

| star | seren | steredenn | steren | réalta | reult, rionnag | rollage |

| today | heddiw | hiziv | hedhyw | inniu | an-diugh | jiu |

| tooth | dant | dant | dans | fiacail | fiacaill, deud | feeackle |

| (to) fall | cwympo | kouezhañ | kodha | tit(im) | tuit(eam) | tuitt(ym) |

| (to) smoke | ysmygu | mogediñ, butuniñ | megi | caith(eamh) tobac | smocadh | toghtaney, smookal |

| (to) whistle | chwibanu | c'hwibanat | hwibana | feadáil | fead | fed |

† Borrowings from Latin.

Examples

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

- Irish: Saoláitear gach duine den chine daonna saor agus comhionann i ndínit agus i gcearta. Tá bua an réasúin agus an choinsiasa acu agus ba cheart dóibh gníomhú i dtreo a chéile i spiorad an bhráithreachais.

- Manx: Ta dagh ooilley pheiagh ruggit seyr as corrym ayns ard-cheim as kiartyn. Ren Jee feoiltaghey resoon as cooinsheanse orroo as by chair daue ymmyrkey ry cheilley myr braaraghyn.

- Scottish Gaelic: Tha gach uile dhuine air a bhreith saor agus co-ionnan ann an urram 's ann an còirichean. Tha iad air am breith le reusan is le cogais agus mar sin bu chòir dhaibh a bhith beò nam measg fhèin ann an spiorad bràthaireil.

- Breton: Dieub ha par en o dellezegezh hag o gwirioù eo ganet an holl dud. Poell ha skiant zo dezho ha dleout a reont bevañ an eil gant egile en ur spered a genvreudeuriezh.

- Cornish: Genys frank ha par yw oll tus an bys yn aga dynita hag yn aga gwiryow. Enduys yns gans reson ha kowses hag y tal dhedha omdhon an eyl orth y gila yn spyrys a vrederedh.

- Welsh: Genir pawb yn rhydd ac yn gydradd â'i gilydd mewn urddas a hawliau. Fe'u cynysgaeddir â rheswm a chydwybod, a dylai pawb ymddwyn y naill at y llall mewn ysbryd cymodlon.

Possibly Celtic languages

It has been suggested that several poorly-documented languages may have been Celtic.

- Ancient Belgian

- Camunic is an extinct language spoken in the first millennium BC in the Val Camonica and Valtellina valleys of the Central Alps. It has recently been proposed to be a Celtic language.[66]

- Ivernic

- Ligurian, in the Northern Mediterranean Coast straddling the southeast French and northwest Italian coasts, including parts of Tuscany, Elba island and Corsica. Xavier Delamarre argues that Ligurian was a Celtic language, similar to Gaulish.[67] The Ligurian-Celtic question is also discussed by Barruol (1999). Ancient Ligurian is either listed as Celtic (epigraphic),[68] or Para-Celtic (onomastic).[44]

- Lusitanian, spoken in the area between the Douro and Tagus rivers of western Iberia (a region straddling the present border of Portugal and Spain). Known from only five inscriptions and various place names.[69] It is an Indo-European language and some scholars have proposed that it may be a para-Celtic language, which evolved alongside Celtic or formed a dialect continuum or sprachbund with Tartessian and Gallaecian. This is tied to a theory of an Iberian origin for the Celtic languages.[69][70][71] It is also possible that the Q-Celtic languages alone, including Goidelic, originated in western Iberia (a theory that was first put forward by Edward Lhuyd in 1707) or shared a common linguistic ancestor with Lusitanian.[72] Secondary evidence for this hypothesis has been found in research by biological scientists, who have identified (1) deep-rooted similarities in human DNA found precisely in both the former Lusitania and Ireland,[73][74] and; (2) the so-called "Lusitanian distribution" of animals and plants unique to western Iberia and Ireland. Both phenomena are now generally thought to have resulted from human emigration from Iberia to Ireland, in the late Paleolithic or early Mesolithic eras.[75] Other scholars see greater linguistic affinities between Lusitanian, proto-Gallo-Italic (particularly with Ligurian) and Old European.[76][77] Prominent modern linguists such as Ellis Evans, believe Gallaecian-Lusitanian was in fact one same language (not separate languages) of the "P" Celtic variant.[78][79]

- Rhaetic, spoken in central Switzerland, Tyrol in Austria, and the Alpine regions of northeast Italy. Documented by a limited number of short inscriptions (found through Northern Italy and Western Austria) in two variants of the Etruscan alphabet. Its linguistic categorization is not clearly established, and it presents a confusing mixture of what appear to be Etruscan, Indo-European, and uncertain other elements. Howard Hayes Scullard argues that Rhaetian was also a Celtic language.[80]

- Tartessian, spoken in the southwest of the Iberia Peninsula (mainly southern Portugal and southwest Spain).[81] Tartessian is known by 95 inscriptions, with the longest having 82 readable signs.[70][82][83] John T. Koch argues that Tartessian was also a Celtic language.[83]

See also

- Ogham

- Celts

- Celts (modern)

- A Swadesh list of the modern Celtic languages

- Celtic Congress

- Celtic League

- Continental Celtic languages

- Italo-Celtic

- Language family

Notes

- The Celtic languages:an overview, Donald MacAulay, The Celtic Languages, ed. Donald MacAulay, (Cambridge University Press, 1992), 3.

- Cunliffe, Barry W. 2003. The Celts: a very short introduction. pg.48

- Alice Roberts, The Celts (Heron Books 2015)

- "Celtic Branch | About World Languages". aboutworldlanguages.com. Archived from the original on 25 September 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 34, 365–366, 529, 973, 1053. ISBN 9781851094400. Archived from the original on 31 December 2015.

- "A brief history of the Cornish language". Maga Kernow. Archived from the original on 25 December 2008.

- Beresford Ellis, Peter (2005) [1990]. The Story of the Cornish Language. Tor Mark Press. pp. 20–22. ISBN 0-85025-371-3.

- "Fockle ny ghaa: schoolchildren take charge". Iomtoday.co.im. Archived from the original on 4 July 2009. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- "'South West:TeachingEnglish:British Council:BBC". BBC/British Council website. BBC. 2010. Archived from the original on 8 January 2010. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- "Celtic Languages". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- Crystal, David (2010). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-73650-3.

- "Irish Examiner - 2004/11/24: EU grants Irish official language status". Irish Examiner. Archives.tcm.ie. 24 November 2004. Archived from the original on 19 January 2005.

- Christina Bratt Paulston (24 March 1994). Linguistic Minorities in Multilingual Settings: Implications for Language Policies. J. Benjamins Pub. Co. p. 81. ISBN 1-55619-347-5.

- Pierce, David (2000). Irish Writing in the Twentieth Century. Cork University Press. p. 1140. ISBN 1-85918-208-9.

- Ó hÉallaithe, Donncha (1999). "Cuisle".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Just 6.3% of Gaeilgeoirí speak Irish on a weekly basis". TheJournal.ie. 23 November 2017. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- "cso.ie Central Statistics Office, Census 2011 – This is Ireland – see table 33a" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- Central Statistics Office. "Population Aged 3 Years and Over by Province County or City, Sex, Ability to Speak Irish and Census Year". Government of Ireland. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- Department of Finance and Personnel. "Census 2011 Key Statistics for Northern Ireland" (PDF). The Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 December 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- "Welsh language skills by local authority, gender and detailed age groups, 2011 Census". StatsWales website. Welsh Government. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- Office for National Statistics 2011 2011-census-key-statistics-for-walesArchived 5 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples – UK: Welsh". United Nations High Commission for Refugees. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "Wales and Argentina". Wales.com website. Welsh Government. 2008. Archived from the original on 16 October 2012. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- "Table 1. Detailed Languages Spoken at Home and Ability to Speak English for the Population 5 Years and Over for the United States: 2006–2008 Release Date: April 2010" (xls). United States Census Bureau. 27 April 2010. Archived from the original on 22 September 2014. Retrieved 2 January 2011.

- "2006 Census of Canada: Topic based tabulations: Various Languages Spoken (147), Age Groups (17A) and Sex (3) for the Population of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2006 Census – 20% Sample Data". Statistics Canada. 7 December 2010. Archived from the original on 26 August 2011. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- StatsWales. "Welsh language skills by local authority, gender and detailed age groups, 2011 Census". Welsh Government. Archived from the original on 31 December 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- (in French) Données clés sur breton, Ofis ar Brezhoneg Archived 15 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Pole Études et Développement Observatoire des Pratiques Linguistiques. "Situation de la Langue". Office Public de la Langue Bretonne. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- 2011 Scotland Census Archived 4 June 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Table QS211SC.

- "National Household Survey Profile, Nova Scotia, 2011". Statistics Canada. 11 September 2013. Archived from the original on 13 May 2014.

- Scotland's Census. "Standard Outputs". National Records of Scotland. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- Alison Campsie. "New bid to get us speaking in Gaelic". The Press and Journal. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- See Number of Cornish speakers

- Around 2,000 fluent speakers. "'South West:TeachingEnglish:British Council:BBC". BBC/British Council website. BBC. 2010. Archived from the original on 8 January 2010. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- Equalities and Wellbeing Division. "Language in England and Wales: 2011". Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- "Anyone here speak Jersey?". The Independent. 11 April 2002. Archived from the original on 11 September 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- "Documentation for ISO 639 identifier: glv". Sil.org. 14 January 2008. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011.

- "Isle of Man Census Report 2011" (PDF). Economic Affairs Division, Isle of Man Government Treasury. April 2012. p. 27. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- Sarah Whitehead (2 April 2015). "How the Manx language came back from the dead". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- "Shelta". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 29 June 2010. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia Archived 31 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine John T. Koch, Vol 1, p. 233

- Schumacher, Stefan; Schulze-Thulin, Britta; aan de Wiel, Caroline (2004). Die keltischen Primärverben. Ein vergleichendes, etymologisches und morphologisches Lexikon (in German). Innsbruck: Institut für Sprachen und Kulturen der Universität Innsbruck. pp. 84–87. ISBN 3-85124-692-6.

- Percivaldi, Elena (2003). I Celti: una civiltà europea. Giunti Editore. p. 82.

- Kruta, Venceslas (1991). The Celts. Thames and Hudson. p. 55.

- Stifter, David (2008). Old Celtic Languages (PDF). p. 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 October 2012. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- MORANDI 2004, pp. 702-703, n. 277

- Prósper, B.M. (2002). Lenguas y religiones prerromanas del occidente de la península ibérica. Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca. pp. 422–27. ISBN 84-7800-818-7.

- Villar F., B. M. Prósper. (2005). Vascos, Celtas e Indoeuropeos: genes y lenguas. Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca. pgs. 333–350. ISBN 84-7800-530-7.

- "In the northwest of the Iberian Peninsula, and more specifically between the west and north Atlantic coasts and an imaginary line running north-south and linking Oviedo and Merida, there is a corpus of Latin inscriptions with particular characteristics of its own. This corpus contains some linguistic features that are clearly Celtic and others that in our opinion are not Celtic. The former we shall group, for the moment, under the label northwestern Hispano-Celtic. The latter are the same features found in well-documented contemporary inscriptions in the region occupied by the Lusitanians, and therefore belonging to the variety known as LUSITANIAN, or more broadly as GALLO-LUSITANIAN. As we have already said, we do not consider this variety to belong to the Celtic language family." Jordán Colera 2007: p.750

- Kenneth H. Jackson suggested that there were two Pictish languages, a pre-Indo-European one and a Pritenic Celtic one. This has been challenged by some scholars. See Katherine Forsyth's "Language in Pictland: the case against 'non-Indo-European Pictish'" "Etext" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 February 2006. Retrieved 20 January 2006. (27.8 MB). See also the introduction by James & Taylor to the "Index of Celtic and Other Elements in W. J. Watson's 'The History of the Celtic Place-names of Scotland'" "Etext" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 February 2006. (172 KB ). Compare also the treatment of Pictish in Price's The Languages of Britain (1984) with his Languages in Britain & Ireland (2000).

- "What are the Celtic Languages?". Celtic Studies Resources. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- Barbour and Carmichael, Stephen and Cathie (2000). Language and nationalism in Europe. Oxford University Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-19-823671-9.

- Gray and Atkinson, RD; Atkinson, QD (2003). "Language-tree divergence times support the Anatolian theory of Indo-European origin". Nature. 426 (6965): 435–439. Bibcode:2003Natur.426..435G. doi:10.1038/nature02029. PMID 14647380. S2CID 42340.

- Rexova, K.; Frynta, D; Zrzavy, J. (2003). "Cladistic analysis of languages: Indo-European classification based on lexicostatistical data". Cladistics. 19 (2): 120–127. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2003.tb00299.x. S2CID 84085451.

- Forster, Peter; Toth, Alfred (2003). "Toward a phylogenetic chronology of ancient Gaulish, Celtic, and Indo-European". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 100 (15): 9079–9084. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.9079F. doi:10.1073/pnas.1331158100. PMC 166441. PMID 12837934.

- Renfrew, Colin (1987). Archaeology and Language: The Puzzle of Indo-European Origins. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 0224024957.

- James, Simon (1999). The Atlantic Celts: Ancient People or Modern Invention?. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 0714121657.

- Stifter, David (2008). Old Celtic Languages (PDF). p. 11. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 October 2012. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- Joseph F. Eska (2010) "The emergence of the Celtic languages". In Martin J. Ball and Nicole Müller (eds.), The Celtic languages. Routledge. ISBN 9781138969995

- Watkins, Calvert, "Italo-Celtic Revisited". In: Birnbaum, Henrik; Puhvel, Jaan, eds. (1966). Ancient Indo-European dialects. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 29–50. OCLC 716409.

- Ringe, Don; Warnow, Tandy; Taylor, Ann (March 2002). "Indo-European and Computational Cladistics" (PDF). Transactions of the Philological Society. 100 (1): 59–129. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.139.6014. doi:10.1111/1467-968X.00091. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- Koch, John T.; Minard, Antone (201). The Celts: History, Life, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-964-6.

- "Dictionnaires bretons parlants". Archived from the original on 7 February 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- "Trinity College Phonetics and Speech Lab". Archived from the original on 12 February 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- "Learn Gaelic Dictionary". Archived from the original on 7 February 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- Markey, Thomas (2008). "Shared Symbolics, Genre Diffusion, Token Perception and Late Literacy in North-Western Europe". NOWELE: North-Western European Language Evolution. NOWELE. 54–55: 5–62. doi:10.1075/nowele.54-55.01mar.

- "Celtic Gods: The Gaulish and Ligurian god, Vasio (He who is given Libation)". Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- Kruta, Venceslas (1991). The Celts. Thames and Hudson. p. 54.

- Wodtko, Dagmar S (2010). Celtic from the West Chapter 11: The Problem of Lusitanian. Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK. pp. 360–361. ISBN 978-1-84217-410-4.

- Cunliffe, Barry (2003). The Celts – A Very Short Introduction – see figure 7. Oxford University Press. pp. 51–52. ISBN 0-19-280418-9.

- Ballester, X. (2004). ""Páramo" o del problema del la */p/ en celtoide". Studi Celtici. 3: 45–56.

- Unity in Diversity, Volume 2: Cultural and Linguistic Markers of the Concept Editors: Sabine Asmus and Barbara Braid. Google Books.

- Hill, E. W.; Jobling, M. A.; Bradley, D. G. (2000). "Y chromosome variation and Irish origins". Nature. 404 (6776): 351–352. Bibcode:2000Natur.404..351H. doi:10.1038/35006158. PMID 10746711. S2CID 4414538.

- McEvoy, B.; Richards, M.; Forster, P.; Bradley, D. G. (2004). "The longue durée of genetic ancestry: multiple genetic marker systems and Celtic origins on the Atlantic facade of Europe". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 75 (4): 693–702. doi:10.1086/424697. PMC 1182057. PMID 15309688.

- Masheretti, S.; Rogatcheva, M. B.; Gündüz, I.; Fredga, K.; Searle, J. B. (2003). "How did pygmy shrews colonize Ireland? Clues from a phylogenetic analysis of mitochondrial cytochrome b sequences". Proc. R. Soc. B. 270 (1524): 1593–1599. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2406. PMC 1691416. PMID 12908980.

- Villar, Francisco (2000). Indoeuropeos y no indoeuropeos en la Hispania Prerromana (in Spanish) (1st ed.). Salamanca: Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca. ISBN 84-7800-968-X. Archived from the original on 31 December 2015.

- The inscription of Cabeço das Fráguas revisited. Lusitanian and Alteuropäisch populations in the West of the Iberian Peninsula Transactions of the Philological Society vol. 97 (2003)

- Callaica_Nomina Archived 30 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine ilg.usc.es

- Celtic Culture: A-Celti. 2006. ISBN 9781851094400.

- Scullard, HH (1967). The Etruscan Cities and Rome. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801403736.

- Koch, John T (2010). Celtic from the West Chapter 9: Paradigm Shift? Interpreting Tartessian as Celtic. Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK. pp. 292–293. ISBN 978-1-84217-410-4.

- Cólera, Carlos Jordán (16 March 2007). "The Celts in the Iberian Peninsula:Celtiberian" (PDF). E-Keltoi. 6: 749–750. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 June 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- Koch, John T (2011). Tartessian 2: The Inscription of Mesas do Castelinho ro and the Verbal Complex. Preliminaries to Historical Phonology. Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK. pp. 1–198. ISBN 978-1-907029-07-3. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011.

References

- Ball, Martin J. & James Fife (ed.) (1993). The Celtic Languages. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-01035-7.

- Borsley, Robert D. & Ian Roberts (ed.) (1996). The Syntax of the Celtic Languages: A Comparative Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521481600.

- Cowgill, Warren (1975). "The origins of the Insular Celtic conjunct and absolute verbal endings". In H. Rix (ed.). Flexion und Wortbildung: Akten der V. Fachtagung der Indogermanischen Gesellschaft, Regensburg, 9.–14. September 1973. Wiesbaden: Reichert. pp. 40–70. ISBN 3-920153-40-5.

- Celtic Linguistics, 1700–1850 (2000). London; New York: Routledge. 8 vols comprising 15 texts originally published between 1706 and 1844.

- Forster, Peter; Toth, Alfred (July 2003). "Toward a phylogenetic chronology of ancient Gaulish, Celtic, and Indo-European". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100 (15): 9079–84. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.9079F. doi:10.1073/pnas.1331158100. PMC 166441. PMID 12837934.

- Gray, Russell D.; Atkinson, Quintin D. (November 2003). "Language-tree divergence times support the Anatolian theory of Indo-European origin". Nature. 426 (6965): 435–39. Bibcode:2003Natur.426..435G. doi:10.1038/nature02029. PMID 14647380. S2CID 42340.

- Hindley, Reg (1990). The Death of the Irish Language: A Qualified Obituary. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-04339-5.

- Lewis, Henry & Holger Pedersen (1989). A Concise Comparative Celtic Grammar. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 3-525-26102-0.

- McCone, Kim (1991). "The PIE stops and syllabic nasals in Celtic". Studia Celtica Japonica. 4: 37–69.

- McCone, Kim (1992). "Relative Chronologie: Keltisch". In R. Beekes; A. Lubotsky; J. Weitenberg (eds.). Rekonstruktion und relative Chronologie: Akten Der VIII. Fachtagung Der Indogermanischen Gesellschaft, Leiden, 31 August – 4 September 1987. Institut für Sprachwissenschaft der Universität Innsbruck. pp. 12–39. ISBN 3-85124-613-6.

- McCone, K. (1996). Towards a Relative Chronology of Ancient and Medieval Celtic Sound Change. Maynooth: Department of Old and Middle Irish, St. Patrick's College. ISBN 0-901519-40-5.

- Russell, Paul (1995). An Introduction to the Celtic Languages. Longman. ISBN 0582100828.

- Schmidt, K.H. (1988). "On the reconstruction of Proto-Celtic". In G. W. MacLennan (ed.). Proceedings of the First North American Congress of Celtic Studies, Ottawa 1986. Ottawa: Chair of Celtic Studies. pp. 231–48. ISBN 0-09-693260-0.

- Schrijver, Peter (1995). Studies in British Celtic historical phonology. Amsterdam: Rodopi. ISBN 90-5183-820-4.

- Schumacher, Stefan; Schulze-Thulin, Britta; aan de Wiel, Caroline (2004). Die keltischen Primärverben. Ein vergleichendes, etymologisches und morphologisches Lexikon (in German). Innsbruck: Institut für Sprachen und Kulturen der Universität Innsbruck. ISBN 3-85124-692-6.

Further reading

- Markey, Thomas L. (2006). “Early Celticity in Slovenia and at Rhaetic Magrè (Schio)”. In: Linguistica 46 (1), 145–72. https://doi.org/10.4312/linguistica.46.1.145-172.

- Sims-Williams, Patrick. “An Alternative to ‘Celtic from the East’ and ‘Celtic from the West’.” In: Cambridge Archaeological Journal 30, no. 3 (2020): 511–29. doi:10.1017/S0959774320000098.

- Stifter, David. "The early Celtic epigraphic evidence and early literacy in Germanic languages". In: NOWELE - North-Western European Language Evolution, Volume 73, Issue 1, Apr 2020, pp. 123–152. ISSN 0108-8416. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1075/nowele.00037.sti

External links

- Celtic languages at Curlie

- Aberdeen University Celtic Department Archived 8 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "Labara: An Introduction to the Celtic Languages", by Meredith Richard

- Celts and Celtic Languages