Charles Lindbergh

Charles Augustus Lindbergh (February 4, 1902 – August 26, 1974) was an American aviator, military officer, author, inventor, and activist. On May 20–21, 1927, Lindbergh made the first nonstop flight from New York City to Paris, a distance of 3,600 miles (5,800 km), flying alone for 33.5 hours. His aircraft, the Spirit of St. Louis, was designed and built by the Ryan Airline Company specifically to compete for the Orteig Prize for the first flight between the two cities. Although not the first transatlantic flight, it was the first solo transatlantic flight, the first nonstop transatlantic flight between two major city hubs, and the longest by over 1,900 miles (3,000 km). It is known as one of the most consequential flights in history and ushered in a new era of air transportation between parts of the globe.

Charles Lindbergh | |

|---|---|

Photo by Harris & Ewing, c. 1927 | |

| Born | Charles Augustus Lindbergh February 4, 1902 Detroit, Michigan, U.S. |

| Died | August 26, 1974 (aged 72) Kipahulu, Hawaii, U.S. |

| Resting place | Palapala Ho'omau Church, Kipahulu |

| Other names |

|

| Education | University of Wisconsin–Madison (no degree) |

| Occupation |

|

| Known for | First solo transatlantic flight (1927), pioneer of international commercial aviation and air mail |

| Spouse | Anne Morrow (m. 1929) |

| Children | 13,[N 1] including Charles Jr., Jon, Anne, and Reeve |

| Parents |

|

| Military career | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1925–1941, 1954–1974 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| Awards |

|

| Signature | |

_signatures.jpg.webp) | |

Lindbergh was raised mostly in Little Falls, Minnesota and Washington, D.C., the son of prominent U.S. Congressman from Minnesota, Charles August Lindbergh. He became an officer in the U.S. Army Air Corps Reserve in 1924, earning the rank of second lieutenant in 1925. Later that year, he was hired as a U.S. Air Mail pilot in the Greater St. Louis area, where he started to prepare for his historic 1927 transatlantic flight. Lindbergh received the United States' highest military decoration from President Calvin Coolidge, the Medal of Honor, as well as the Distinguished Flying Cross for his transatlantic flight.[4] The flight also earned him the highest French order of merit, civil or military, the Legion of Honor.[5] His achievement spurred significant global interest in both commercial aviation and air mail, which revolutionized the aviation industry worldwide (described then as the "Lindbergh boom"), and he devoted much time and effort to promoting such activity. He was honored as Time's first Man of the Year in 1928, was appointed to the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics in 1929 by President Herbert Hoover, and was awarded a Congressional Gold Medal in 1930. In 1931, he and French surgeon Alexis Carrel began work on inventing the first perfusion pump, which is credited with making future heart surgeries and organ transplantation possible.

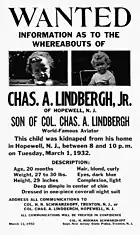

On March 1, 1932, Lindbergh's first-born infant child, Charles Jr., was kidnapped and murdered in what the American media called the "Crime of the Century". The case prompted the United States Congress to establish kidnapping as a federal crime if a kidnapper crosses state lines with a victim. By late 1935, the press and hysteria surrounding the case had driven the Lindbergh family into exile in Europe, from where they returned in 1939.

In the months before the United States entered World War II, Lindbergh's non-interventionist stance and statements about Jews and race led some to believe he was a Nazi sympathizer, although Lindbergh never publicly stated support for the Nazis and condemned them several times in both his public speeches and in his personal diary. However, like many Americans before the attack on Pearl Harbor, he opposed not only the military intervention of the United States but also the provision of military supplies to the British.[6] He supported the isolationist America First Committee and resigned his commission in the U.S. Army Air Forces in April 1941 after President Franklin Roosevelt publicly rebuked him for his views. In September 1941, Lindbergh gave a significant address, titled "Speech on Neutrality", outlining his position and arguments against greater American involvement in the war.[7]

Lindbergh ultimately expressed public support for the U.S. war effort after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and declaration of war on Germany, but was rejected for active duty as Roosevelt refused to restore his Air Corps colonel's commission.[8] Instead he flew 50 combat missions in the Pacific Theater as a civilian consultant and was unofficially credited with shooting down an enemy aircraft.[9][10] In 1954, President Dwight Eisenhower restored his commission and promoted him to brigadier general in the U.S. Air Force Reserve.[11] In his later years, Lindbergh became a prolific author, international explorer, inventor, and environmentalist, eventually dying of lymphoma in 1974 at age 72.

Early life

Early childhood

Lindbergh was born in Detroit, Michigan, on February 4, 1902, and spent most of his childhood in Little Falls, Minnesota, and Washington, D.C. He was the only child of Charles August Lindbergh (birth name Carl Månsson; 1859–1924), who had emigrated from Sweden to Melrose, Minnesota, as an infant, and Evangeline Lodge Land Lindbergh (1876–1954) of Detroit. Lindbergh had three elder paternal half-sisters: Lillian, Edith, and Eva. The couple separated in 1909 when Lindbergh was seven years old.[12][13] His father, a U.S. Congressman (R-MN-6) from 1907 to 1917, was one of the few congressmen to oppose the entry of the U.S. into World War I (although his congressional term ended one month before the House of Representatives voted to declare war on Germany).[14] His father's book Why Is Your Country at War?, which criticized the nation's entry into the war, was seized by federal agents under the Comstock Act. It was later posthumously reprinted and issued in 1934 under the title Your Country at War, and What Happens to You After a War.[15]

Lindbergh's mother was a chemistry teacher at Cass Technical High School in Detroit and later at Little Falls High School, from which her son graduated on June 5, 1918. Lindbergh attended more than a dozen other schools from Washington, D.C., to California during his childhood and teenage years (none for more than a year or two), including the Force School and Sidwell Friends School while living in Washington with his father, and Redondo Union High School in Redondo Beach, California, while living there with his mother.[16] Although he enrolled in the College of Engineering at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in late 1920, Lindbergh dropped out in the middle of his sophomore year and then went to Lincoln, Nebraska, in March 1922 to begin flight training.[17]

Early aviation career

From an early age, Lindbergh had exhibited an interest in the mechanics of motorized transportation, including his family's Saxon Six automobile, and later his Excelsior motorbike. By the time that he started college as a mechanical engineering student, he had also become fascinated with flying, though he "had never been close enough to a plane to touch it".[18] After quitting college in February 1922, Lindbergh enrolled at the Nebraska Aircraft Corporation's flying school in Lincoln and flew for the first time on April 9 as a passenger in a two-seat Lincoln Standard "Tourabout" biplane trainer piloted by Otto Timm.[19]

A few days later, Lindbergh took his first formal flying lesson in that same aircraft, though he was never permitted to solo because he could not afford to post the requisite damage bond.[20] To gain flight experience and earn money for further instruction, Lindbergh left Lincoln in June to spend the next few months barnstorming across Nebraska, Kansas, Colorado, Wyoming, and Montana as a wing walker and parachutist. He also briefly worked as an airplane mechanic at the Billings, Montana, municipal airport.[21][22]

Lindbergh left flying with the onset of winter and returned to his father's home in Minnesota.[23] His return to the air and his first solo flight did not come until half a year later in May 1923 at Souther Field in Americus, Georgia, a former Army flight-training field, where he bought a World War I surplus Curtiss JN-4 "Jenny" biplane. Though Lindbergh had not touched an airplane in more than six months, he had already secretly decided that he was ready to take to the air by himself. After a half-hour of dual time with a pilot who was visiting the field to pick up another surplus JN-4, Lindbergh flew solo for the first time in the Jenny that he had just purchased for $500.[24][25] After spending another week or so at the field to "practice" (thereby acquiring five hours of "pilot in command" time), Lindbergh took off from Americus for Montgomery, Alabama, some 140 miles to the west, for his first solo cross-country flight.[26] He went on to spend much of the remainder of 1923 engaged in almost nonstop barnstorming under the name of "Daredevil Lindbergh". Unlike in the previous year, this time Lindbergh flew in his "own ship" as the pilot.[27][28] A few weeks after leaving Americus, he achieved another key aviation milestone when he made his first night flight near Lake Village, Arkansas.[29]

While Lindbergh was barnstorming in Lone Rock, Wisconsin, on two occasions he flew a local physician across the Wisconsin River to emergency calls that were otherwise unreachable because of flooding.[30] He broke his propeller several times while landing, and on June 3, 1923 he was grounded for a week when he ran into a ditch in Glencoe, Minnesota, while flying his father—then running for the U.S. Senate—to a campaign stop. In October, Lindbergh flew his Jenny to Iowa, where he sold it to a flying student. After selling the Jenny, Lindbergh returned to Lincoln by train. There, he joined Leon Klink and continued to barnstorm through the South for the next few months in Klink's Curtiss JN-4C "Canuck" (the Canadian version of the Jenny). Lindbergh also "cracked up" this aircraft once when his engine failed shortly after takeoff in Pensacola, Florida, but again he managed to repair the damage himself.[31]

Following a few months of barnstorming through the South, the two pilots parted company in San Antonio, Texas, where Lindbergh reported to Brooks Field on March 19, 1924 to begin a year of military flight training with the United States Army Air Service there (and later at nearby Kelly Field).[32] Lindbergh had his most serious flying accident on March 5, 1925, eight days before graduation, when a mid-air collision with another Army S.E.5 during aerial combat maneuvers forced him to bail out.[33] Only 18 of the 104 cadets who started flight training a year earlier remained when Lindbergh graduated first overall in his class in March 1925, thereby earning his Army pilot's wings and a commission as a second lieutenant in the Air Service Reserve Corps.[34][N 2]

Lindbergh later said that this year was critical to his development as both a focused, goal-oriented individual and as an aviator.[N 3] The Army did not need additional active-duty pilots, however, so immediately following graduation, Lindbergh returned to civilian aviation as a barnstormer and flight instructor, although as a reserve officer he also continued to do some part-time military flying by joining the 110th Observation Squadron, 35th Division, Missouri National Guard, in St. Louis. He was promoted to first lieutenant on December 7, 1925, and to captain in July 1926.[37]

Air mail pilot

In October 1925, Lindbergh was hired by the Robertson Aircraft Corporation (RAC) at the Lambert-St. Louis Flying Field in Anglum, Missouri, (where he had been working as a flight instructor) to first lay out and then serve as chief pilot for the newly designated 278-mile (447 km) Contract Air Mail Route #2 (CAM-2) to provide service between St. Louis and Chicago (Maywood Field) with two intermediate stops in Springfield and Peoria, Illinois.[38] Lindbergh and three other RAC pilots, Philip R. Love, Thomas P. Nelson, and Harlan A. "Bud" Gurney, flew the mail over CAM-2 in a fleet of four modified war-surplus de Havilland DH-4 biplanes.

Just before signing on to fly with CAM, Lindbergh had applied to serve as a pilot on Richard E. Byrd's North Pole expedition, but apparently his bid came too late.[39]

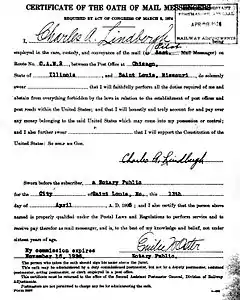

On April 13, 1926, Lindbergh executed the United States Post Office Department's Oath of Mail Messengers,[40] and two days later he opened service on the new route. On two occasions, combinations of bad weather, equipment failure, and fuel exhaustion forced him to bail out on night approach to Chicago;[41][42] both times he reached the ground without serious injury and immediately set about ensuring that his cargo was located and sent on with minimum delay.[42][43] In mid-February 1927 he left for San Diego, California, to oversee design and construction of the Spirit of St. Louis.[44]

New York–Paris flight

Orteig Prize

In 1919, British aviators John Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown won the Daily Mail prize for the first nonstop transatlantic flight. Their aircraft was a Vickers Vimy IV biplane designed for service in WW1. Alcock and Brown left St. John's, Newfoundland, on June 14, 1919, and arrived in Ireland the following day.[45]

Around the same time, French-born New York hotelier Raymond Orteig was approached by Augustus Post, secretary of the Aero Club of America, and prompted to put up a $25,000 award for the first successful nonstop transatlantic flight specifically between New York City and Paris (in either direction) within five years after its establishment. When that time limit lapsed in 1924 without a serious attempt, Orteig renewed the offer for another five years, this time attracting a number of well-known, highly experienced, and well-financed contenders[46]—none of whom was successful. On September 21, 1926, World War I French flying ace René Fonck's Sikorsky S-35 crashed on takeoff from Roosevelt Field in New York. U.S. Naval aviators Noel Davis and Stanton H. Wooster were killed at Langley Field, Virginia, on April 26, 1927, while testing their Keystone Pathfinder. On May 8 French war heroes Charles Nungesser and François Coli departed Paris – Le Bourget Airport in the Levasseur PL 8 seaplane L'Oiseau Blanc; they disappeared somewhere in the Atlantic after last being seen crossing the west coast of Ireland.[47]

American air racer Clarence D. Chamberlin and Arctic explorer Richard E. Byrd were also in the race.

Spirit of St. Louis

.jpg.webp)

Financing the operation of the historic flight was a challenge due to Lindbergh's obscurity, but two St. Louis businessmen eventually obtained a $15,000 bank loan. Lindbergh contributed $2,000 ($29,036.61 in 2020)[48] of his own money from his salary as an air mail pilot and another $1,000 was donated by RAC. The total of $18,000 was far less than what was available to Lindbergh's rivals.[49]

The group tried to buy an "off-the-peg" single or multiengine monoplane from Wright Aeronautical, then Travel Air, and finally the newly formed Columbia Aircraft Corporation, but all insisted on selecting the pilot as a condition of sale.[50][51][52] Finally the much smaller Ryan Aircraft Company of San Diego agreed to design and build a custom monoplane for $10,580, and on February 25 a deal was formally closed.[53] Dubbed the Spirit of St. Louis, the fabric-covered, single-seat, single-engine "Ryan NYP" (for "New York-Paris") high-wing monoplane (CAB registration: N-X-211) was designed jointly by Lindbergh and Ryan's chief engineer Donald A. Hall.[54] The Spirit flew for the first time just two months later, and after a series of test flights Lindbergh took off from San Diego on May 10. He went first to St. Louis, then on to Roosevelt Field on New York's Long Island.[55]

Flight

.jpg.webp)

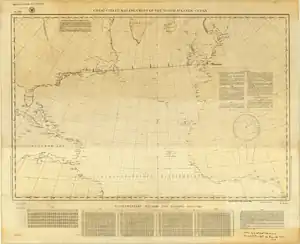

In the early morning of Friday, May 20, 1927, Lindbergh took off from Roosevelt Field, Long Island.[56][57] His monoplane was loaded with 450 U.S. gallons (1,704 liters) of fuel that was strained repeatedly to avoid fuel line blockage. The fully loaded aircraft weighed 2.7 tons (2329 kilograms), with takeoff hampered by a muddy, rain-soaked runway. Lindbergh's monoplane was powered by a J-5C Wright Whirlwind radial engine and gained speed very slowly during its 7:52 a.m. takeoff, but cleared telephone lines at the far end of the field "by about twenty feet [six meters] with a fair reserve of flying speed".[58]

Over the next 33+1⁄2 hours, Lindbergh and the Spirit faced many challenges, which included skimming over storm clouds at 10,000 ft (3,000 m) and wave tops at as low as 10 ft (3.0 m). The aircraft fought icing, flew blind through fog for several hours, and Lindbergh navigated only by dead reckoning (he was not proficient at navigating by the sun and stars and he rejected radio navigation gear as heavy and unreliable). He was fortunate that the winds over the Atlantic cancelled each other out, giving him zero wind drift—and thus accurate navigation during the long flight over featureless ocean.[59][60] He landed at Le Bourget Aerodrome[61] at 10:22 p.m. on Saturday, May 21.[62] The airfield was not marked on his map and Lindbergh knew only that it was some seven miles northeast of the city; he initially mistook it for some large industrial complex because of the bright lights spreading out in all directions—in fact the headlights of tens of thousands of spectators' cars caught in "the largest traffic jam in Paris history" in their attempt to be present for Lindbergh's landing.[63]

A crowd estimated at 150,000 stormed the field, dragged Lindbergh out of the cockpit, and carried him around above their heads for "nearly half an hour". Some damage was done to the Spirit (especially to the fine linen, silver-painted fabric covering on the fuselage) by souvenir hunters before pilot and plane reached the safety of a nearby hangar with the aid of French military fliers, soldiers, and police.[64] Among the crowd were two future Indian prime ministers, Jawaharlal Nehru and his daughter, Indira Gandhi.[65]

Lindbergh's flight was certified by the National Aeronautic Association of the United States based on the readings from a sealed barograph placed in the Spirit.[66][67]

Global fame

Lindbergh received unprecedented adulation after his historic flight. People were "behaving as though Lindbergh had walked on water, not flown over it".[69]: 17 The New York Times printed an above the fold, page-wide headline: "Lindbergh Does It!"[70] His mother's house in Detroit was surrounded by a crowd estimated at 1,000.[71] Countless newspapers, magazines, and radio shows wanted to interview him, and he was flooded with job offers from companies, think tanks, and universities.

The French Foreign Office flew the American flag, the first time it had saluted someone who was not a head of state.[72] Lindbergh also made a series of brief flights to Belgium and Great Britain in the Spirit before returning to the United States. Gaston Doumergue, the President of France, bestowed the French Légion d'honneur on Lindbergh,[73] and on his arrival back in the United States aboard the U.S. Navy cruiser USS Memphis (CL-13) on June 11, 1927, a fleet of warships and multiple flights of military aircraft escorted him up the Potomac River to the Washington Navy Yard, where President Calvin Coolidge awarded him the Distinguished Flying Cross.[74][75] Lindbergh received the first award of this medal, but it violated the authorizing regulation. Coolidge's own executive order, published in March 1927, required recipients to perform their feats of airmanship "while participating in an aerial flight as part of the duties incident to such membership [in the Organized Reserves]", which Lindbergh very clearly failed to satisfy.[76][77] The U.S. Post Office Department issued a 10-cent air mail stamp (Scott C-10) depicting the Spirit and a map of the flight.

Lindbergh flew from Washington, D.C., to New York City on June 13, arriving in Lower Manhattan. He traveled up the Canyon of Heroes to City Hall, where he was received by Mayor Jimmy Walker. A ticker-tape parade[79] followed to Central Park Mall, where he was honored at another ceremony hosted by New York Governor Al Smith and attended by a crowd of 200,000. Some 4,000,000 people saw Lindbergh that day.[80][81][82] That evening, Lindbergh was accompanied by his mother and Mayor Walker when he was the guest of honor at a 500-guest banquet and dance held at Clarence MacKay's Long Island estate, Harbor Hill.[83]

The following night, Lindbergh was honored with a grand banquet at the Hotel Commodore given by the Mayor's Committee on Receptions of the City of New York and attended by some 3,700 people.[84] He was officially awarded the check for the prize on June 16.[68]

On July 18, 1927, Lindbergh was promoted to the rank of colonel in the Air Corps of the Officers Reserve Corps of the U.S. Army.[85]

On December 14, 1927, a Special Act of Congress awarded Lindbergh the Medal of Honor, despite the fact that it was almost always awarded for heroism in combat.[86] It was presented to Lindbergh by President Coolidge at the White House on March 21, 1928.[87] Curiously, the medal contradicted Coolidge's earlier executive order directing that "not more than one of the several decorations authorized by Federal law will be awarded for the same act of heroism or extraordinary achievement" (Lindbergh was recognized for the same act with both the Medal of Honor and the Distinguished Flying Cross).[88] The statute authorizing the award was also criticized for apparently violating procedure; House legislators reportedly neglected to have their votes counted.[89] Similar noncombat awards of the Medal of Honor were also authorized by special statutes and awarded to naval aviators Richard E. Byrd and Floyd Bennett, as well as arctic explorer Adolphus W. Greely. In addition, the Medal of Honor awarded to General Douglas MacArthur was reportedly based on the Lindbergh precedent, although MacArthur notably lacked implementing legislation, which probably rendered his award unlawful.[90]

Lindbergh was honored as the first Time magazine Man of the Year (now called "Person of the Year") when he appeared on that magazine's cover at age 25 on January 2, 1928;[91] he remained the youngest Time Person of the Year until Greta Thunberg surpassed his record in 2019. The winner of the 1930 Best Woman Aviator of the Year Award, Elinor Smith Sullivan, said that before Lindbergh's flight:

People seemed to think we [aviators] were from outer space or something. But after Charles Lindbergh's flight, we could do no wrong. It's hard to describe the impact Lindbergh had on people. Even the first walk on the moon doesn't come close. The twenties was such an innocent time, and people were still so religious—I think they felt like this man was sent by God to do this. And it changed aviation forever because all of a sudden the Wall Streeters were banging on doors looking for airplanes to invest in. We'd been standing on our heads trying to get them to notice us but after Lindbergh, suddenly everyone wanted to fly, and there weren't enough planes to carry them.[92]

Autobiography and tours

Barely two months after Lindbergh arrived in Paris, G. P. Putnam's Sons published his 318-page autobiography "WE", which was the first of 15 books he eventually wrote or to which he made significant contributions. The company was run by aviation enthusiast George P. Putnam.[93] The dustjacket notes said that Lindbergh wanted to share the "story of his life and his transatlantic flight together with his views on the future of aviation", and that "WE" referred to the "spiritual partnership" that had developed "between himself and his airplane during the dark hours of his flight".[94][95] But Putnam's had selected the title without Lindbergh's knowledge, and he complained, "we" actually referred to himself and his St. Louis financial backers, though his frequent unconscious use of the phrase seemed to suggest otherwise.[96]

"WE" was soon translated into most major languages and sold more than 650,000 copies in the first year, earning Lindbergh more than $250,000. Its success was considerably aided by Lindbergh's three-month, 22,350-mile (35,970 km) tour of the United States in the Spirit on behalf of the Daniel Guggenheim Fund for the Promotion of Aeronautics. Between July 20 and October 23, 1927, Lindbergh visited 82 cities in all 48 states, delivered 147 speeches, rode 1,290 mi (2,080 km) in parades,[96][N 4] and was seen by more than 30 million Americans, one quarter of the nation's population.[96]

Lindbergh then toured 16 Latin American countries between December 13, 1927, and February 8, 1928. Dubbed the "Good Will Tour", it included stops in Mexico (where he also met his future wife, Anne, the daughter of U.S. Ambassador Dwight Morrow), Guatemala, British Honduras, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, the Canal Zone, Colombia, Venezuela, St. Thomas, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Cuba, covering 9,390 miles (15,110 km) in just over 116 hours of flight time.[37][97] A year and two days after it had made its first flight, Lindbergh flew the Spirit from St. Louis to Washington, D.C., where it has been on public display at the Smithsonian Institution ever since.[98] Over the previous 367 days, Lindbergh and the Spirit had logged 489 hours 28 minutes of flight time together.[99]

A "Lindbergh boom" in aviation had begun. The volume of mail moving by air increased 50 percent within six months, applications for pilots' licenses tripled, and the number of planes quadrupled.[69]: 17 President Herbert Hoover appointed Lindbergh to the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics.[100]

Lindbergh and Pan American World Airways head Juan Trippe were interested in developing a great circle air route across Alaska and Siberia to China and Japan. In the summer of 1931, with Trippe's support, Lindbergh and his wife flew from Long Island to Nome, Alaska, and from there to Siberia, Japan and China. The flight was carried out with a Lockheed Model 8 Sirius named Tingmissartoq. The route was not available for commercial service until after World War II, as prewar aircraft lacked the range to fly Alaska to Japan nonstop, and the United States had not officially recognized the Soviet government.[101] In China they volunteered to help in disaster investigation and relief efforts for the Central China flood of 1931.[102] This was later documented in Anne's book North to the Orient.

Air mail promotion

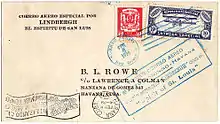

Lindbergh used his world fame to promote air mail service. For example, at the request of Basil L. Rowe, the owner of West Indian Aerial Express (and later Pan Am's chief pilot), in February, 1928, he carried some 3,000 pieces of special souvenir mail between Santo Domingo, R.D.; Port-au-Prince, Haiti; and Havana, Cuba[103]—the last three stops he and the Spirit made during their 7,800 mi (12,600 km) "Good Will Tour" of Latin America and the Caribbean between December 13, 1927, and February 8, 1928, and the only franked mail pieces that he ever flew in the his iconic plane.[104]

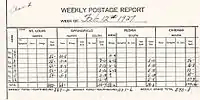

Two weeks after his Latin American tour, Lindbergh piloted a series of special flights over his old CAM-2 route on February 20 and February 21. Tens of thousands of self-addressed souvenir covers were sent in from all over the world, so at each stop Lindbergh switched to another of the three planes he and his fellow CAM-2 pilots had used, so it could be said that each cover had been flown by him. The covers were then backstamped and returned to their senders as promotion of the air mail service.[105]

In 1929–1931, Lindbergh carried much smaller numbers of souvenir covers on the first flights over routes in Latin America and the Caribbean, which he had earlier laid out as a consultant to Pan American Airways to be then flown under contract to the Post Office as Foreign Air Mail (FAM) routes 5 and 6.[106]

Personal life

American family

In his autobiography, Lindbergh derided pilots he met as womanizing "barnstormers"; he also criticized Army cadets for their "facile" approach to relationships. He wrote that the ideal romance was stable and long-term, with a woman with keen intellect, good health, and strong genes,[107] his "experience in breeding animals on our farm [having taught him] the importance of good heredity".[108]

Anne Morrow Lindbergh (1906–2001) was the daughter of Dwight Morrow, who, as a partner at J.P. Morgan & Co., had acted as financial adviser to Lindbergh. He was also the U.S. Ambassador to Mexico in 1927. Invited by Morrow on a goodwill tour to Mexico along with humorist and actor Will Rogers, Lindbergh met Anne in Mexico City in December 1927.[109]

The couple was married on May 27, 1929, at the Morrow estate in Englewood, New Jersey, where they resided after their marriage before moving to their home in the western part of the state.[110][111] They had six children: Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr. (1930–1932); Jon Morrow Lindbergh (1932–2021); Land Morrow Lindbergh (b. 1937), who studied anthropology at Stanford University and married Susan Miller in San Diego;[112] Anne Lindbergh (1940–1993); Scott Lindbergh (b. 1942); and Reeve Lindbergh (b. 1945), a writer. Lindbergh taught Anne how to fly, and she accompanied and assisted him in much of his exploring and charting of air routes.

Lindbergh saw his children for only a few months a year. He kept track of each child's infractions (including such things as gum-chewing) and insisted that Anne track every penny of household expenses in account books.[113]

Lindbergh's grandson, aviator Erik Lindbergh (one of 8 children of Jon Lindbergh), has had notable involvement in both the private spaceflight and electric aircraft industries.[114][115]

Kidnapping of Charles Lindbergh Jr.

On the evening of March 1, 1932, twenty-month-old Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr. was abducted from his crib in the Lindberghs' rural home, Highfields, in East Amwell, New Jersey, near the town of Hopewell.[N 5] A man who claimed to be the kidnapper[117] picked up a cash ransom of $50,000 on April 2, part of which was in gold certificates, which were soon to be withdrawn from circulation and would therefore attract attention; the bills' serial numbers were also recorded. On May 12, the child's remains were found in woods not far from the Lindbergh home.[118]

The case was widely called the "Crime of the Century" and was described by H. L. Mencken as "the biggest story since the Resurrection".[119] In response, Congress passed the so-called "Lindbergh Law", which made kidnapping a federal offense if the victim is taken across state lines or (as in the Lindbergh case) the kidnapper uses "the mail or ... interstate or foreign commerce in committing or in furtherance of the commission of the offense", such as in demanding ransom.[120]

Richard Hauptmann, a 34-year-old German immigrant carpenter, was arrested near his home in the Bronx, New York, on September 19, 1934, after paying for gasoline with one of the ransom bills. $13,760 of the ransom money and other evidence was found in his home. Hauptmann went on trial for kidnapping, murder and extortion on January 2, 1935, in a circus-like atmosphere in Flemington, New Jersey. He was convicted on February 13,[121] sentenced to death, and electrocuted at Trenton State Prison on April 3, 1936.[122]

In Europe (1936–1939)

An intensely private man,[123] Lindbergh became exasperated by the unrelenting public attention in the wake of the kidnapping and Hauptmann trial,[124][125] and was concerned for the safety of his three-year-old second son, Jon.[126][127] Consequently, in the predawn hours of Sunday, December 22, 1935, the family "sailed furtively"[124] from Manhattan for Liverpool,[128] the only three passengers aboard the United States Lines freighter SS American Importer.[N 6] They traveled under assumed names and with diplomatic passports issued through the personal intervention of former U.S. Treasury Secretary Ogden L. Mills.[130]

News of the Lindberghs' "flight to Europe"[124] did not become public until a full day later,[131][132] and even after the identity of their ship became known[125] radiograms addressed to Lindbergh on it were returned as "Addressee not aboard".[124] They arrived in Liverpool on December 31, then departed for South Wales to stay with relatives.[133][134]

The family eventually rented "Long Barn" in Sevenoaks Weald, Kent.[135] In 1938, the family (including a third son, Land, born May 1937 in London) moved to Île Illiec, a small four-acre (1.6 ha) island Lindbergh purchased off the Breton coast of France.[136]

Except for a brief visit to the U.S. in December 1937,[137] the Lindberghs lived and traveled extensively around Europe in their personal Miles M.12 Mohawk, before returning to the U.S. in April 1939 and settling in a rented seaside estate at Lloyd Neck, Long Island, New York.[138][139] The return was prompted by a personal request by General H. H. ("Hap") Arnold, the chief of the United States Army Air Corps in which Lindbergh was a reserve colonel, for him to accept a temporary return to active duty to help evaluate the Air Corps's readiness for war.[140][141] His duties included evaluating new aircraft types in development, recruitment procedures, and finding a site for a new air force research institute and other potential air bases.[142] Assigned a Curtiss P-36 fighter, he toured various facilities, reporting back to Wright Field.[142] Lindbergh's brief four-month tour was also his first period of active military service since his graduation from the Army's Flight School fourteen years earlier in 1925.[138]

Scientific activities

Lindbergh wrote to the Longines watch company and described a watch that would make navigation easier for pilots. First produced in 1931,[143] it is still produced today.[144]

In 1929, Lindbergh became interested in the work of rocket pioneer Robert H. Goddard. By helping Goddard secure an endowment from Daniel Guggenheim in 1930, Lindbergh allowed Goddard to expand his research and development. Throughout his life, Lindbergh remained a key advocate of Goddard's work.[145]

In 1930, Lindbergh's sister-in-law developed a fatal heart condition.[146] Lindbergh began to wonder why hearts could not be repaired with surgery. Starting in early 1931 at the Rockefeller Institute and continuing during his time living in France, Lindbergh studied the perfusion of organs outside the body with Nobel Prize-winning French surgeon Alexis Carrel. Although perfused organs were said to have survived surprisingly well, all showed progressive degenerative changes within a few days.[147] Lindbergh's invention, a glass perfusion pump, named the "Model T" pump, is credited with making future heart surgeries possible. In this early stage, the pump was far from perfected. In 1938, Lindbergh and Carrel described an artificial heart in the book in which they summarized their work, The Culture of Organs,[148] but it was decades before one was built. In later years, Lindbergh's pump was further developed by others, eventually leading to the construction of the first heart-lung machine.[149]

Pre-war activities and politics

Overseas visits

At the request of the United States military, Lindbergh traveled to Germany several times between 1936 and 1938 to evaluate German aviation.[150] Hanna Reitsch demonstrated the Focke-Wulf Fw 61 helicopter to Lindbergh in 1937,[151]: 121 and he was the first American to examine Germany's newest bomber, the Junkers Ju 88, and Germany's front-line fighter aircraft, the Messerschmitt Bf 109, which he was allowed to pilot. He said of the Bf 109 that he knew of "no other pursuit plane which combines simplicity of construction with such excellent performance characteristics".[150][152]

There is disagreement on how accurate Lindbergh's reports were, but Cole asserts that the consensus among British and American officials was that they were slightly exaggerated but badly needed.[153] Arthur Krock, the chief of The New York Times's Washington Bureau, wrote in 1939, "When the new flying fleet of the United States begins to take air, among those who will have been responsible for its size, its modernness, and its efficiency is Colonel Charles A. Lindbergh. Informed officials here, in touch with what Colonel Lindbergh has been doing for his country abroad, are authority for this statement, and for the further observation that criticism of any of his activities – in Germany or elsewhere – is as ignorant as it is unfair."[154] General Henry H. Arnold, the only U.S. Air Force general to hold five-star rank, wrote in his autobiography, "Nobody gave us much useful information about Hitler's air force until Lindbergh came home in 1939."[155] Lindbergh also undertook a survey of aviation in the Soviet Union in 1938.[156]

In 1938, Hugh Wilson, the American ambassador to Germany, hosted a dinner for Lindbergh with Germany's air chief, Generalfeldmarschall Hermann Göring, and three central figures in German aviation: Ernst Heinkel, Adolf Baeumker, and Willy Messerschmitt.[157] At this dinner, Göring presented Lindbergh with the Commander Cross of the Order of the German Eagle. Lindbergh's acceptance proved controversial after Kristallnacht, an anti-Jewish pogrom in Germany a few weeks later.[158] Lindbergh declined to return the medal, later writing, "It seems to me that the returning of decorations, which were given in times of peace and as a gesture of friendship, can have no constructive effect. If I were to return the German medal, it seems to me that it would be an unnecessary insult. Even if war develops between us, I can see no gain in indulging in a spitting contest before that war begins."[159] Regarding this, Ambassador Wilson later wrote to Lindbergh, "Neither you, nor I, nor any other American present had any previous hint that the presentation would be made. I have always felt that if you refused the decoration, presented under those circumstances, you would have been guilty of a breach of good taste. It would have been an act offensive to a guest of the Ambassador of your country, in the house of the Ambassador."[154]

Isolationism and America First Committee

In 1938, the U.S. Air Attaché in Berlin invited Lindbergh to inspect the rising power of Nazi Germany's Air Force. Impressed by German technology and the apparently-large number of aircraft at their disposal and influenced by the staggering number of deaths from World War I, he opposed U.S. entry into the impending European conflict.[160] In September 1938, he stated to the French cabinet that the Luftwaffe possessed 8,000 aircraft and could produce 1,500 per month. Although this was seven times the actual number determined by the Deuxième Bureau, it influenced France into trying to avoid conflict with Nazi Germany through the Munich Agreement.[161] At the urging of U.S. Ambassador Joseph Kennedy, Lindbergh wrote a secret memo to the British warning that a military response by Britain and France to Hitler's violation of the Munich Agreement would be disastrous; he claimed that France was militarily weak and Britain over-reliant on its navy. He urgently recommended that they strengthen their air power to force Hitler to redirect his aggression against "Asiatic Communism".[153]

Following Hitler's invasion of Czechoslovakia and Poland, Lindbergh opposed sending aid to countries under threat, writing "I do not believe that repealing the arms embargo would assist democracy in Europe" and[160] "If we repeal the arms embargo with the idea of assisting one of the warring sides to overcome the other, then why mislead ourselves by talk of neutrality?"[160] He equated assistance with war profiteering: "To those who argue that we could make a profit and build up our own industry by selling munitions abroad, I reply that we in America have not yet reached a point where we wish to capitalize on the destruction and death of war."[160]

In August 1939, Lindbergh was the first choice of Albert Einstein, whom he met years earlier in New York, to deliver the Einstein–Szilárd letter alerting President Roosevelt about the vast potential of nuclear fission. However, Lindbergh did not respond to Einstein's letter or to Szilard's later letter of September 13. Two days later, Lindbergh gave a nationwide radio address, in which he called for isolationism and indicated some pro-German sympathies and antisemitic insinuations about Jewish ownership of the media, saying "We must ask who owns and influences the newspaper, the news picture, and the radio station, ... If our people know the truth, our country is not likely to enter the war". After that, Szilard stated to Einstein: "Lindbergh is not our man."[162]: 475

In October 1939, following the outbreak of hostilities between Britain and Germany, and a month after the Canadian declaration of war on Germany, Lindbergh made another nationwide radio address criticizing Canada for drawing the Western Hemisphere "into a European war simply because they prefer the Crown of England" to the independence of the Americas.[163][164] Lindbergh went on to further state his opinion that the entire continent and its surrounding islands needed to be free from the "dictates of European powers".[163][164]

In November 1939, Lindbergh authored a controversial Reader's Digest article in which he deplored the war, but asserted the need for a German assault on the Soviet Union.[153] Lindbergh wrote: "Our civilization depends on peace among Western nations ... and therefore on united strength, for Peace is a virgin who dare not show her face without Strength, her father, for protection."[165][166]

In late 1940, Lindbergh became the spokesman of the isolationist America First Committee,[167] soon speaking to overflow crowds at Madison Square Garden and Chicago's Soldier Field, with millions listening by radio. He argued emphatically that America had no business attacking Germany. Lindbergh justified this stance in writings that were only published posthumously:

I was deeply concerned that the potentially gigantic power of America, guided by uninformed and impractical idealism, might crusade into Europe to destroy Hitler without realizing that Hitler's destruction would lay Europe open to the rape, loot and barbarism of Soviet Russia's forces, causing possibly the fatal wounding of Western civilization.[168]

In April 1941, he argued before 30,000 members of the America First Committee that "the British government has one last desperate plan ... to persuade us to send another American Expeditionary Force to Europe and to share with England militarily, as well as financially, the fiasco of this war."[169]

In his 1941 testimony before the House Committee on Foreign Affairs opposing the Lend-Lease bill, Lindbergh proposed that the United States negotiate a neutrality pact with Germany.[170] President Franklin Roosevelt publicly decried Lindbergh's views as those of a "defeatist and appeaser", comparing him to U.S. Rep. Clement L. Vallandigham, who had led the "Copperhead" movement opposed to the American Civil War. Lindbergh promptly resigned his commission as a colonel in the U.S. Army Air Corps, writing that he saw "no honorable alternative" given that Roosevelt had publicly questioned his loyalty.[171]

At an America First rally in September, Lindbergh accused three groups of "pressing this country toward war; the British, the Jewish, and the Roosevelt Administration":[172]

It is not difficult to understand why Jewish people desire the overthrow of Nazi Germany. The persecution they suffered in Germany would be sufficient to make bitter enemies of any race.

No person with a sense of the dignity of mankind can condone the persecution of the Jewish race in Germany. But no person of honesty and vision can look on their pro-war policy here today without seeing the dangers involved in such a policy both for us and for them. Instead of agitating for war, the Jewish groups in this country should be opposing it in every possible way for they will be among the first to feel its consequences.

Tolerance is a virtue that depends upon peace and strength. History shows that it cannot survive war and devastations. A few far-sighted Jewish people realize this and stand opposed to intervention. But the majority still do not.

Their greatest danger to this country lies in their large ownership and influence in our motion pictures, our press, our radio and our government.

He continued:

I am not attacking either the Jewish or the British people. Both races, I admire. But I am saying that the leaders of both the British and the Jewish races, for reasons which are as understandable from their viewpoint as they are inadvisable from ours, for reasons which are not American, wish to involve us in the war. We cannot blame them for looking out for what they believe to be their own interests, but we also must look out for ours. We cannot allow the natural passions and prejudices of other peoples to lead our country to destruction.[174]

His message was popular throughout many Northern communities and especially well received in the Midwest, while the American South was anglophilic and supported a pro-British foreign policy.[175] The South was the most pro-British and interventionist part of the country.[176] Responding to criticism of his speech,[177] Anne Lindbergh felt that the speech might tarnish Lindbergh's reputation unjustly; she wrote in her diary:

I have the greatest faith in [Lindbergh] as a person—in his integrity, his courage, and his essential goodness, fairness, and kindness—his nobility really ... How then explain my profound feeling of grief about what he is doing? If what he said is the truth (and I am inclined to think it is), why was it wrong to state it? He was naming the groups that were pro-war. No one minds his naming the British or the Administration. But to name "Jew" is un-American—even if it is done without hate or even criticism. Why?[178]

Lindbergh's reaction to Kristallnacht, in November 1938, was entrusted to his diary: "I do not understand these riots on the part of the Germans", he wrote. "It seems so contrary to their sense of order and intelligence. They have undoubtedly had a difficult 'Jewish problem', but why is it necessary to handle it so unreasonably?"[179] Lindbergh had planned to move to Berlin for the winter of 1938–39. He had provisionally found a house in Wannsee, but after Nazi friends discouraged him from leasing it because it had been formerly owned by Jews,[180] it was recommended that he contact Albert Speer, who said he would build the Lindberghs a house anywhere they wanted. On the advice of his close friend Alexis Carrel, he cancelled the trip.[180]

In his diaries, he wrote, "We must limit to a reasonable amount the Jewish influence ... Whenever the Jewish percentage of total population becomes too high, a reaction seems to invariably occur. It is too bad because a few Jews of the right type are, I believe, an asset to any country."

Alleged Nazi sympathies and views on race

Lindbergh's anticommunism resonated deeply with many Americans, while his eugenics and Nordicism enjoyed social acceptance.[166] His speeches and writings reflected his adoption of views on race, religion, and eugenics, similar to those of the German Nazis, and he was suspected of being a Nazi sympathizer.[181][182] However, during a speech in September 1941, Lindbergh stated "no person with a sense of the dignity of mankind can condone the persecution of the Jewish race in Germany."[183] Interventionist pamphlets pointed out that his efforts were praised in Nazi Germany and included quotations such as "Racial strength is vital; politics, a luxury".[184]

Roosevelt disliked Lindbergh's outspoken opposition to his administration's interventionist policies, telling Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, "If I should die tomorrow, I want you to know this, I am absolutely convinced Lindbergh is a Nazi."[185] In 1941 he wrote to Secretary of War Henry Stimson: "When I read Lindbergh's speech I felt that it could not have been better put if it had been written by Goebbels himself. What a pity that this youngster has completely abandoned his belief in our form of government and has accepted Nazi methods because apparently they are efficient."[186] Shortly after the war ended, Lindbergh toured a Nazi concentration camp, and wrote in his diary, "Here was a place where men and life and death had reached the lowest form of degradation. How could any reward in national progress even faintly justify the establishment and operation of such a place?"[183]

Lindbergh seemed to state that he believed the survival of the white race was more important than the survival of democracy in Europe: "Our bond with Europe is one of race and not of political ideology", he declared.[187] Critics have noticed an apparent influence on Lindbergh of German philosopher Oswald Spengler.[188] Spengler was a conservative authoritarian popular during the interwar period, though he had fallen out of favor with the Nazis because he had not wholly subscribed to their theories of racial purity.[188]

Lindbergh developed a long-term friendship with the automobile pioneer Henry Ford, who was well known for his antisemitic newspaper The Dearborn Independent. In a famous comment about Lindbergh to Detroit's former FBI field office special agent in charge in July 1940, Ford said: "When Charles comes out here, we only talk about the Jews."[189][190]

Lindbergh considered Russia a "semi-Asiatic" country compared to Germany, and he believed Communism was an ideology that would destroy the West's "racial strength" and replace everyone of European descent with "a pressing sea of Yellow, Black, and Brown". He stated that if he had to choose, he would rather see America allied with Nazi Germany than Soviet Russia. He preferred Nordics, but he believed, after Soviet Communism was defeated, Russia would be a valuable ally against potential aggression from East Asia.[188][191]

Lindbergh elucidated his beliefs regarding the white race in a 1939 article in Reader's Digest:

We can have peace and security only so long as we band together to preserve that most priceless possession, our inheritance of European blood, only so long as we guard ourselves against attack by foreign armies and dilution by foreign races.[192]

Lindbergh said certain races have "demonstrated superior ability in the design, manufacture, and operation of machines",[193] and that "The growth of our western civilization has been closely related to this superiority."[194] Lindbergh admired "the German genius for science and organization, the English genius for government and commerce, the French genius for living and the understanding of life". He believed, "in America they can be blended to form the greatest genius of all".[195]

In his book The American Axis, Holocaust researcher and investigative journalist Max Wallace agreed with Franklin Roosevelt's assessment that Lindbergh was "pro-Nazi". However, he found that the Roosevelt Administration's accusations of dual loyalty or treason were unsubstantiated. Wallace considered Lindbergh to be a well-intentioned but bigoted and misguided Nazi sympathizer whose career as the leader of the isolationist movement had a destructive impact on Jewish people.[196]

Lindbergh's Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer, A. Scott Berg, contended that Lindbergh was not so much a supporter of the Nazi regime as someone so stubborn in his convictions and relatively inexperienced in political maneuvering that he easily allowed rivals to portray him as one. Lindbergh's receipt of the Order of the German Eagle, presented in October 1938 by Generalfeldmarschall Hermann Göring on behalf of Führer Adolf Hitler, was approved without objection by the American embassy; the award did not cause controversy until after World War II began in September 1939. Lindbergh returned to the United States in early 1939 to spread his message of nonintervention. Berg contended Lindbergh's views were commonplace in the United States in the interwar era. Lindbergh's support for the America First Committee was representative of the sentiments of a number of American people.[197]

Berg also noted: "As late as April 1939—after Germany overtook Czechoslovakia—Lindbergh was willing to make excuses for Adolf Hitler. 'Much as I disapprove of many things Hitler had done', he wrote in his diary on April 2, 1939, 'I believe she [Germany] has pursued the only consistent policy in Europe in recent years. I cannot support her broken promises, but she has only moved a little faster than other nations ... in breaking promises. The question of right and wrong is one thing by law and another thing by history.'" Berg also explained that leading up to the war, Lindbergh believed the great battle would be between the Soviet Union and Germany, not fascism and democracy.

Wallace noted that it was difficult to find social scientists among Lindbergh's contemporaries in the 1930s who found validity in racial explanations for human behavior. Wallace went on to observe, "throughout his life, eugenics would remain one of Lindbergh's enduring passions".[198]

Lindbergh always championed military strength and alertness.[199][200] He believed that a strong defensive war machine would make America an impenetrable fortress and defend the Western Hemisphere from an attack by foreign powers, and that this was the U.S. military's sole purpose.[201]

Berg writes that while the attack on Pearl Harbor came as a shock to Lindbergh, he did predict that America's "wavering policy in the Philippines" would invite a brutal war there, and in one speech warned, "we should either fortify these islands adequately, or get out of them entirely."[202]

World War II

In January 1942, Lindbergh met with Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson, seeking to be recommissioned in the Army Air Forces. Stimson was strongly opposed because of the long record of public comments.[203] Blocked from active military service, Lindbergh approached a number of aviation companies and offered his services as a consultant. As a technical adviser with Ford in 1942, he was heavily involved in troubleshooting early problems at the Willow Run Consolidated B-24 Liberator bomber production line. As B-24 production smoothed out, he joined United Aircraft in 1943 as an engineering consultant, devoting most of his time to its Chance-Vought Division.[204]

In 1944 Lindbergh persuaded United Aircraft to send him as a technical representative to the Pacific Theater to study aircraft performance under combat conditions. He demonstrated how United States Marine Corps Aviation pilots could take off safely with a bomb load double the Vought F4U Corsair fighter-bomber's rated capacity. At the time, several Marine squadrons were flying bomber escorts to destroy the Japanese stronghold of Rabaul, New Britain, in the Australian Territory of New Guinea. On May 21, 1944, Lindbergh flew his first combat mission: a strafing run with VMF-222 near the Japanese garrison of Rabaul.[205] He also flew with VMF-216, from the Marine Air Base at Torokina, Bougainville. Lindbergh was escorted on one of these missions by Lt. Robert E. (Lefty) McDonough, who refused to fly with Lindbergh again, as he did not want to be known as "the guy who killed Lindbergh".[205]

In his six months in the Pacific in 1944, Lindbergh took part in fighter bomber raids on Japanese positions, flying 50 combat missions (again as a civilian).[206] His innovations in the use of Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighters impressed a supportive Gen. Douglas MacArthur.[207] Lindbergh introduced engine-leaning techniques to P-38 pilots, greatly improving fuel consumption at cruise speeds, enabling the long-range fighter aircraft to fly longer-range missions. P-38 pilot Warren Lewis quoted Lindbergh's fuel-saving settings, "He said, '... we can cut the RPM down to 1400RPMs and use 30 inches of mercury (manifold pressure), and save 50–100 gallons of fuel on a mission.'"[208] The U.S. Marine and Army Air Force pilots who served with Lindbergh praised his courage and defended his patriotism.[205][209]

On July 28, 1944, during a P-38 bomber escort mission with the 433rd Fighter Squadron in the Ceram area, Lindbergh shot down a Mitsubishi Ki-51 "Sonia" observation plane, piloted by Captain Saburo Shimada, commanding officer of the 73rd Independent Chutai.[10][205]

Lindbergh's participation in combat was revealed in a story in the Passaic Herald-News on October 22, 1944.[9]

In mid-October 1944, Lindbergh participated in a joint Army-Navy conference on fighter planes at NAS Patuxent River, Maryland.[210]

After the war, Lindbergh toured the Nazi concentration camps and wrote in his autobiography that he was disgusted and angered.[N 7]

Later life

After World War II, Lindbergh lived in Darien, Connecticut, and served as a consultant to the Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force and to Pan American World Airways. With most of eastern Europe under communist control, Lindbergh believed that his prewar assessments of the Soviet threat were correct. Lindbergh witnessed firsthand the defeat of Germany and the Holocaust, and Berg reported, "he knew the American public no longer gave a hoot about his opinions". On April 7, 1954, on the recommendation of President Dwight D. Eisenhower, Lindbergh was commissioned a brigadier general in the U.S. Air Force Reserve; Eisenhower nominated Lindbergh for promotion on February 15.[3][11][212][213] Also in that year, he served on a Congressional advisory panel that recommended the site of the United States Air Force Academy.[214]

In December 1968, he visited the crew of Apollo 8 (the first manned mission to orbit the Moon) the day before their launch, and in 1969 he watched the launch of Apollo 11.[215] In conjunction with the first lunar landing, he shared his thoughts as part of Walter Cronkite's live television coverage. He later wrote the foreword to Apollo astronaut Michael Collins's autobiography.[216]

Double life and secret German children

Beginning in 1957, General Lindbergh engaged in lengthy sexual relationships with three women while remaining married to Anne Morrow. He fathered three children with hatmaker Brigitte Hesshaimer (1926–2001), who had lived in the small Bavarian town of Geretsried. He had two children with her sister Mariette, a painter, living in Grimisuat. Lindbergh also had a son and daughter (born in 1959 and 1961) with Valeska, an East Prussian aristocrat who was his private secretary in Europe and lived in Baden-Baden.[217][218][219][220] All seven children were born between 1958 and 1967.[2]

Ten days before he died, Lindbergh wrote to each of his European mistresses, imploring them to maintain the utmost secrecy about his illicit activities with them even after his death.[221] The three women (none of whom ever married) all managed to keep their affairs secret even from their children, who during his lifetime (and for almost a decade after his death) did not know the true identity of their father, whom they had only known by the alias Careu Kent and seen only when he briefly visited them once or twice a year. However, after reading a magazine article about Lindbergh in the mid-1980s, Brigitte's daughter Astrid deduced the truth; she later discovered snapshots and more than 150 love letters from Lindbergh to her mother. After Brigitte and Anne Lindbergh had both died, she made her findings public; in 2003 DNA tests confirmed that Lindbergh had fathered Astrid and her two siblings.[2][222] Reeve Lindbergh, Lindbergh's youngest child with Anne, wrote in her personal journal in 2003, "This story reflects absolutely Byzantine layers of deception on the part of our shared father. These children did not even know who he was! He used a pseudonym with them (To protect them, perhaps? To protect himself, absolutely!)"[223]

Environmental causes

In later life Lindbergh was heavily involved in conservation movements, and was deeply concerned about the negative impacts of new technologies on the natural world and native peoples, in particular on Hawaii.[224][225] He campaigned to protect endangered species such as the humpback whale, blue whale,[225] Philippine eagle, the tamaraw (a rare dwarf Philippine buffalo), and was instrumental in establishing protections for the Tasaday people, and various African tribes such as the Maasai.[225] Alongside Laurance S. Rockefeller, Lindbergh helped establish the Haleakalā National Park in Hawaii.[226]

Lindbergh's speeches and writings in later life emphasized technology and nature, and his lifelong belief that "all the achievements of mankind have value only to the extent that they preserve and improve the quality of life".[224]

Death

Lindbergh spent his last years on the Hawaiian island of Maui, where he died of lymphoma[227] on August 26, 1974, at age 72. He was buried on the grounds of the Palapala Ho'omau Church in Kipahulu, Maui. His epitaph, on a simple stone following the words "Charles A. Lindbergh Born Michigan 1902 Died Maui 1974", quotes Psalm 139:9: "If I take the wings of the morning, and dwell in the uttermost parts of the sea ... C.A.L."[228]

Honors and tributes

- Lindbergh was a recipient of the Silver Buffalo Award, the highest adult award given by the Boy Scouts of America, on April 10, 1928, in San Francisco.[229]

- On May 8, 1928, a statue was dedicated at the entrance to Le Bourget Airport in Paris honoring Lindbergh and his New York to Paris flight as well as Charles Nungesser and François Coli who had attempted the same feat two weeks earlier in the other direction aboard L'Oiseau Blanc (The White Bird), disappearing without a trace.

- Several U.S. airports have been named for Lindbergh.

- In 1933, the Lindbergh Range (Danish: Lindbergh Fjelde) in Greenland was named after him by Danish Arctic explorer Lauge Koch following aerial surveys made during the 1931–1934 Three-year Expedition to East Greenland.[230]

- In St. Louis County, Missouri, a school district, high school and highway are named for Lindbergh, and he has a star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame.[231]

- In 1937, a transatlantic race was proposed to commemorate the tenth anniversary of Lindbergh's flight to Paris, though it was eventually modified to take a different course of similar length (see 1937 Istres–Damascus–Paris Air Race).

- He was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1967.

- The Royal Air Force Museum in London minted a medal with his image as part of a 50 medal set called The History of Man in Flight in 1972.[232]

- The original Lindbergh residence in Little Falls, Minnesota is maintained as a museum, and is listed as a National Historic Landmark.[233][234]

- In February 2002, the Medical University of South Carolina at Charleston, within the celebrations for the Lindbergh 100th birthday established the Lindbergh-Carrel Prize,[235] given to major contributors to "development of perfusion and bioreactor technologies for organ preservation and growth". M. E. DeBakey and nine other scientists[236] received the prize, a bronze statuette expressly created for the event by the Italian artist C. Zoli and named "Elisabeth", after Elisabeth Morrow, sister of Lindbergh's wife Anne Morrow, who died as a result of heart disease.[237] Lindbergh was disappointed that contemporary medical technology could not provide an artificial heart pump that would allow for heart surgery on Elisabeth and that led to the first contact between Carrel and Lindbergh.[237]

Awards and decorations

Lindbergh received many awards, medals and decorations, most of which were later donated to the Missouri Historical Society and are on display at the Jefferson Memorial, now part of the Missouri History Museum in Forest Park in St. Louis, Missouri.[238]

- United States government

Medal of Honor (1927)

Medal of Honor (1927) Distinguished Flying Cross (1927)

Distinguished Flying Cross (1927)- Langley Gold Medal from the Smithsonian Institution (1927)

- Congressional Gold Medal (1928)

- other United States

- Orteig Prize (1927, see details above)

- Harmon Trophy (1927)

- Hubbard Medal (1927)

- Honorary Scout (Boy Scouts of America, 1927)[239]

- Silver Buffalo Award (Boy Scouts of America, 1928)[240]

- Wright Brothers Memorial Trophy (1949)

- Daniel Guggenheim Medal (1953)

- Pulitzer Prize (1954)

- Non-U.S. awards

_Ribbon_bar.svg.png.webp) Knight of the Order of Leopold (Belgium, 1927)

Knight of the Order of Leopold (Belgium, 1927) Air Force Cross (United Kingdom, 1927)

Air Force Cross (United Kingdom, 1927) Commander of the Legion of Honor (France, 1931)[5]

Commander of the Legion of Honor (France, 1931)[5] Order of the German Eagle with Star (Nazi Germany, October 19, 1938)[241]

Order of the German Eagle with Star (Nazi Germany, October 19, 1938)[241]- Fédération Aéronautique Internationale FAI Gold Medal (1927)

- ICAO Edward Warner Award (1975)[242]

- Royal Swedish Aero Clubs Gold plaque (1927)[243]

Medal of Honor

Rank and organization: Captain, U.S. Army Air Corps Reserve. Place and date: From New York City to Paris, France, May 20–21, 1927. Entered service at: Little Falls, Minn. Born: February 4, 1902, Detroit, Mich. G.O. No.: 5, W.D., 1928; Act of Congress December 14, 1927.[244][N 8]

- Citation

For displaying heroic courage and skill as a navigator, at the risk of his life, by his nonstop flight in his airplane, the "Spirit of St. Louis", from New York City to Paris, France, 20–21 May 1927, by which Capt. Lindbergh not only achieved the greatest individual triumph of any American citizen but demonstrated that travel across the ocean by aircraft was possible.[248]

Books

In addition to "WE" and The Spirit of St. Louis, Lindbergh wrote prolifically over the years on other topics, including science, technology, nationalism, war, materialism, and values. Included among those writings were five other books: The Culture of Organs (with Dr. Alexis Carrel) (1938), Of Flight and Life (1948), The Wartime Journals of Charles A. Lindbergh (1970), Boyhood on the Upper Mississippi (1972), and his unfinished Autobiography of Values (posthumous, 1978).[254][255]

In popular culture

Literature

In addition to many biographies, such as A. Scott Berg's 1998 award-winning bestseller Lindbergh, Lindbergh also influenced or was the model for characters in a variety of works of fiction.[256] Shortly after he made his famous flight, the Stratemeyer Syndicate began publishing a series of books for juvenile readers called the Ted Scott Flying Stories (1927–1943), which were written by a number of authors all using the nom de plume "Franklin W. Dixon", in which the pilot hero was closely modeled after Lindbergh. Ted Scott duplicated the solo flight to Paris in the series' first volume, entitled Over the Ocean to Paris published in 1927.[257] Another reference to Lindbergh appears in the Agatha Christie novel (1934) and movie Murder on the Orient Express (1974) which begins with a fictionalized depiction of the Lindbergh kidnapping.[258]

There have been several alternate history novels depicting Lindbergh's alleged Nazi-sympathies and non-interventionist views during the first half of World War II. In Daniel Easterman's K is for Killing (1997), a fictional Lindbergh becomes president of a fascist United States. The Philip Roth novel The Plot Against America (2004) explores an alternate history where Franklin Delano Roosevelt is defeated in the 1940 presidential election by Lindbergh, who allies the United States with Nazi Germany.[259] The novel draws heavily on Lindbergh's comments concerning Jews as a catalyst for its plot.[187] The Robert Harris novel Fatherland (1992) explores an alternate history where the Nazis won the war, the United States still defeats Japan, Adolf Hitler and President Joseph Kennedy negotiate peace terms, and Lindbergh is the US Ambassador to Germany. The Jo Walton novel Farthing (2006) explores an alternate history where the United Kingdom made peace with Nazi Germany in 1941, Japan never attacked Pearl Harbor, thus the United States never got involved with the war, and Lindbergh is president and is seeking closer economic ties with the Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere.

Film and television

- The 1942 MGM picture Keeper of the Flame (Katharine Hepburn, Spencer Tracy) features Hepburn as the widow of Robert V. Forrest, a "Lindbergh-like" national hero.[260]

- In the motion picture The Spirit of St. Louis, directed by Billy Wilder and released in 1957, Lindbergh was played by Jimmy Stewart, an admirer of Lindbergh and himself an aviator who had flown bombing missions in World War II. The film largely centers around Lindbergh's record-breaking 1927 flight.[261] Prior to the casting of Stewart, John Kerr declined to play the role in the film because of Lindbergh's alleged pro-Nazi beliefs.[262]

- In 1976, Buzz Kulik's TV movie The Lindbergh Kidnapping Case, with Anthony Hopkins as Richard Bruno Hauptmann, premiered on NBC February 26.[263]

- Lindbergh was the theme of prolific director Orson Welles's final living film project, The Spirit of Charles Lindbergh, where Welles speaks of the human spirit while quoting Lindbergh's journal. Although never intended to be viewed by the public, a brief clip can be seen at the end of Vassili Slovic's 1995 documentary Orson Welles: the One-Man Band.

- Lindbergh has been the subject of numerous documentary films, including Charles A. Lindbergh (1927), a UK documentary by De Forest Phonofilm; 40,000 Miles with Lindbergh (1928) featuring Lindbergh himself; and The American Experience—Lindbergh: The Shocking, Turbulent Life of America's Lone Eagle (1988).[264][265][266]

- The 2020 HBO alternate history miniseries The Plot Against America, based on the Philip Roth book of the same name, features actor Ben Cole as a fictional President Lindbergh following his defeat of Roosevelt in 1940. The series portrays Lindbergh as a xenophobic populist with strong ties to Nazi Germany.

- Charles Lindbergh "Chuck" McGill, a fictional character in the TV series Better Call Saul (2015–2022), was named after Lindbergh.[267]

Music

Within days of the flight, dozens of Tin Pan Alley publishers rushed a variety of popular songs into print celebrating Lindbergh and the Spirit of St. Louis including "Lindbergh (The Eagle of the U.S.A.)" by Howard Johnson and Al Sherman, and "Lucky Lindy!" by L. Wolfe Gilbert and Abel Baer. In the two-year period following Lindbergh's flight, the U.S. Copyright Office recorded three hundred applications for Lindbergh songs.[268][269] Tony Randall revived "Lucky Lindy" in an album of Jazz Age and Depression-era songs that he recorded titled Vo Vo De Oh Doe (1967).[270]

While the exact origin of the name of the Lindy Hop is disputed, it is widely acknowledged that Lindbergh's 1927 flight helped to popularize the dance: soon after "Lucky Lindy" "hopped" the Atlantic, it would become a trendy, fashionable dance, and songs referring to the "Lindbergh Hop" were soon released.[271][272][273][274]

In 1929, Bertolt Brecht wrote a cantata called Der Lindberghflug (Lindbergh's Flight) with music by Kurt Weill and Paul Hindemith. Because of Lindbergh's apparent Nazi sympathies, in 1950 Brecht removed all direct references to Lindbergh and renamed the piece Der Ozeanflug (The Flight Across the Ocean).[275]

In the early 1940s Woody Guthrie wrote "Lindbergh" or "Mister Charlie Lindbergh"[276] which criticizes Lindbergh's involvement with the America First Committee and his suspected sympathy for Nazi Germany.

Postage stamps

Lindbergh and the Spirit have been honored by a variety of world postage stamps over the last eight decades, including three issued by the United States. Less than three weeks after the flight the U.S. Post Office Department issued a 10-cent "Lindbergh Air Mail" stamp (Scott C-10) on June 11, 1927, with engraved illustrations of both the Spirit of St. Louis and a map of its route from New York to Paris. This was also the first U.S. stamp to bear the name of a living person.[277] A half-century later, a 13-cent commemorative stamp (Scott #1710) depicting the Spirit flying low over the Atlantic Ocean was issued on May 20, 1977, the 50th anniversary of the flight from Roosevelt Field.[278] On May 28, 1998, a 32¢ stamp with the legend "Lindbergh Flies Atlantic" (Scott #3184m) depicting Lindbergh and the Spirit was issued as part of the Celebrate the Century stamp sheet series.[279]

Other

During World War II, Lindbergh was a frequent target of Dr. Seuss's first political cartoons, published in the New York magazine PM, in which Geisel criticized Lindbergh's antisemitism and supposed Nazi sympathies.[280]

Lindbergh's Spirit of St. Louis is featured in the opening sequence of Star Trek: Enterprise (2001–2005), which aimed to follow the "evolution of exploration" by featuring significant designs throughout history, starting with the HMS Enterprise frigate and Montgolfière baloon, to the Wright Flyer III, Spirit of St. Louis and Bell X-1, up through the Lunar Module Eagle, Space Shuttle Enterprise, Mars rover Sojourner, and International Space Station.[281]

St. Louis area–based GoJet Airlines uses the callsign "Lindbergh" after Charles Lindbergh.

See also

- Amelia Earhart

- Bernt Balchen

- Beryl Markham

- Charles Kingsford Smith

- Clyde Pangborn

- Douglas Corrigan

- First aerial crossing of the South Atlantic

- History of aviation

- List of firsts in aviation

- List of Medal of Honor recipients in non-combat incidents

- List of peace activists

- List of people on stamps of Ireland

- Third man factor

- Uncommon Friends of the 20th Century (1999 documentary)

- Vikingsholm

Notes

- Lindbergh fathered a total of 13 children throughout his life—six with long-time wife Anne Morrow, the first-born of which, Charles Jr., was kidnapped and murdered in his infancy; and seven other children with three separate European women out of wedlock.[2]

- Dates of military rank: Cadet, Army Air Corps – March 19, 1924, 2nd Lieutenant, Officer Reserve Corps (ORC) – March 14, 1925, 1st Lieutenant, ORC – December 7, 1925, Captain, ORC – July 13, 1926, Colonel, ORC – July 18, 1927 (As of 1927, Lindbergh was a member of the Missouri National Guard and was assigned to the 110th Observation Squadron in St. Louis.[35]), Brigadier General, USAFR – April 7, 1954.[36]

- "Always there was some new experience, always something interesting going on to make the time spent at Brooks and Kelly one of the banner years in a pilot's life. The training is difficult and rigid, but there is none better. A cadet must be willing to forget all other interest in life when he enters the Texas flying schools and he must enter with the intention of devoting every effort and all of the energy during the next 12 months towards a single goal. But when he receives the wings at Kelly a year later, he has the satisfaction of knowing that he has graduated from one of the world's finest flying schools." "WE" p. 125

- Cities in which Lindbergh and the Spirit of St. Louis landed during the Guggenheim Tour included: New York, N.Y.; Hartford, Conn.; Providence, R.I.; Boston, Mass.; Concord, N.H.; Orchard Beach & Portland, Me.; Springfield, Vt.; Albany, Schenectady, Syracuse, Rochester, & Buffalo, N.Y.; Cleveland, Ohio; Pittsburgh, Pa.; Wheeling, W.V.; Dayton & Cincinnati, Ohio; Louisville, Ky.; Indianapolis, Ind.; Detroit & Grand Rapids, Mich.; Chicago & Springfield, Ill.; St. Louis & Kansas City, Mo.; Wichita, Kan.; St. Joseph, Mo.; Moline, Ill.; Milwaukee & Madison, Wis.; Minneapolis/St. Paul & Little Falls, Minn.; Fargo, N.D.; Sioux Falls, S.D.; Des Moines, Iowa; Omaha, Neb.; Denver, Colo.; Pierre, S.D.; Cheyenne, Wyo.; Salt Lake City, Utah; Boise, Idaho; Butte & Helena, Mont.; Spokane & Seattle, Wash.; Portland, Ore.; San Francisco, Oakland, & Sacramento, Calif.; Reno, Nev.; Los Angeles & San Diego, Calif.; Tucson, Ariz.; Lordsburg, N.M.; El Paso, Texas; Santa Fe, N.M.; Abilene, Fort Worth & Dallas, Texas; Oklahoma City, Tulsa & Muskogee, Okla.; Little Rock, Ark.; Memphis & Chattanooga, Tenn.; Birmingham, Alabama; Jackson, Miss.; New Orleans, La.; Jacksonville, Fla.; Spartensburg, S.C.; Greensboro & Winston-Salen, N.C.; Richmond, Va.; Washington, D.C.; Baltimore, Md.; Atlantic City, N.J.; Wilmington, Del.; Philadelphia, Pa.; New York, N.Y.

- Quote: So while the world's attention was focused on Hopewell, from which the first press dispatches emanated about the kidnapping, the Democrat made sure its readers knew that the new home of Col. Charles A. Lindbergh and Anne Morrow Lindbergh was in East Amwell Township, Hunterdon County.[116]

- Lindbergh's "flight to Europe" ship SS American Importer was sold to Société Maritime Anversoise, Antwerp, Belgium in February 1940 and renamed Ville de Gand. Just after midnight on August 19, 1940 the vessel was torpedoed by the German submarine U-48 about 200 miles west of Ireland while sailing from Liverpool to New York and sank with the loss of 14 crew.[129]

- In a stream of consciousness manner, Lindbergh detailed his visit immediately after World War II to a Nazi concentration camp, and his reactions. In the Japanese edition, there are no entries about Nazi camps. Instead, there is an entry recorded in his diary that he often witnessed atrocities against Japanese POWs by Australians and Americans.[211]

- In 1927, the Medal of Honor could still be awarded for extraordinarily heroic non-combat actions by active or reserve service members made during peacetime with almost all such medals being awarded to active-duty members of the United States Navy for rescuing or attempting to rescue persons from drowning. In addition to Lindbergh, Floyd Bennett and Richard Evelyn Byrd of the Navy, were also presented with the medal for their accomplishments as explorers for their participation in the first successful heavier-than-air flight to the North Pole and back.[245][246][247]

References

- Every and Tracy 1927, pp. 60, 84, 99, 208.

- Schröck, Rudolf The Lone Eagle's Clandestine Nests. Charles Lindbergh's German secrets". Archived May 3, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. The Atlantic Times, June 2005

- "Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr. | Interim 1920 - 1940 | U.S. Army Air Corps Reserve | Medal of Honor Recipient". Congressional Medal of Honor Society. Archived from the original on October 7, 2021. Retrieved October 7, 2021.