Crabeater seal

The crabeater seal (Lobodon carcinophaga), also known as the krill-eater seal, is a true seal with a circumpolar distribution around the coast of Antarctica. They are medium- to large-sized (over 2 m in length), relatively slender and pale-colored, found primarily on the free-floating pack ice that extends seasonally out from the Antarctic coast, which they use as a platform for resting, mating, social aggregation and accessing their prey. They are by far the most abundant seal species in the world. While population estimates are uncertain, there are at least 7 million and possibly as many as 75 million individuals.[2] This success of this species is due to its specialized predation on the abundant Antarctic krill of the Southern Ocean, for which it has uniquely adapted, sieve-like tooth structure. Indeed, its scientific name, translated as "lobe-toothed (lobodon) crab eater (carcinophaga)", refers specifically to the finely lobed teeth adapted to filtering their small crustacean prey.[3] Despite its name, crabeater seals do not eat crabs. As well as being an important krill predator, the crabeater seal's pups are an important component of the diet of leopard seals (Hydrurga leptonyx), which are responsible for 80% of all crabeater pups deaths. This is the only species in the genus Lobodon.

| Crabeater seal | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Clade: | Pinnipedia |

| Family: | Phocidae |

| Genus: | Lobodon Gray, 1844 |

| Species: | L. carcinophaga |

| Binomial name | |

| Lobodon carcinophaga Hombron & Jacquinot, 1842 | |

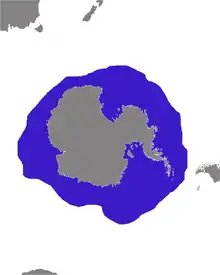

| |

| Distribution of crabeater seal | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Lobodon carcinophagus | |

Taxonomy and evolution

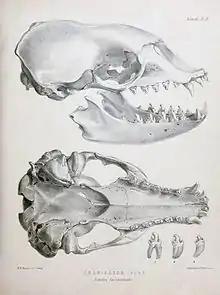

The genus name of the crabeater seal, Lobodon, derives from Ancient Greek meaning "lobe-toothed", and the species name carcinophaga means "crab eater."[3] The crabeater seal shares a common recent ancestor with the other Antarctic seals, which are together known as the lobodontine seals. These include the leopard seal (Hydrurga leptonyx), the Ross seal (Ommatophoca rossii), and the Weddell seal (Leptonychotes weddelli).[4] These species, collectively belonging to the Lobodontini tribe of seals, share teeth adaptations including lobes and cusps useful for straining smaller prey items out of the water column. The ancestral Lobodontini likely diverged from their sister clade, the Mirounga (elephant seals) in the late Miocene to early Pliocene, when they migrated southward and diversified rapidly in the relative isolation around Antarctica.[4]

Description

Adult seals (over five years old) grow to an average length of 2.3 m (7.5 ft) and an average weight of around 200 kg (440 lb). Females are on average 6 cm (2.4 in) longer and around 8 kilograms (18 lb) heavier than males, though their weights fluctuate substantially according to season; females can lose up to 50% of their body weight during lactation, and males lose a significant proportion of weight as they attend to their mating partners and fight off rivals.[5] During summer, males typically weigh 200 kilograms (440 lb), and females 215 kilograms (474 lb). A molecular genetic based technique has been established to confirm the sex of individuals in the laboratory.[6] Large crabeater seals can weigh up to 300 kg (660 lb).[7] Pups are about 1.2 metres (3.9 ft) in length and 20 to 30 kilograms (44 to 66 lb) at birth. While nursing, pups grow at a rate of about 4.2 kilograms (9.3 lb) a day, and grow to be around 100 kilograms (220 lb) when they are weaned at two or three weeks.[3][8]

These seals are covered mostly by brown or silver fur, with darker coloration around flippers. The color fades throughout the year, and recently molted seals appear darker than the silvery-white crabeater seals that are about to molt. Their body is comparatively more slender than other seals, and the snout is pointed. Crabeater seals can raise their heads and arch their backs while on ice, and they are able to move quickly if not subject to overheating. Crabeater seals exhibit scarring either from leopard seal attacks around the flippers or, for males, during the breeding season while fighting for mates around the throat and jaw.[3] Pups are born with a light brown, downy pelage (lanugo), until the first molt at weaning. Younger animals are marked by net-like, chocolate brown markings and flecks on the shoulders, sides and flanks, shading into the predominantly dark hind and fore flippers and head, often due to scarring from leopard seals. After molting, their fur is a darker brown fading to blonde on their bellies. The fur lightens throughout the year, becoming completely blonde in summer.

Crabeaters have relatively slender bodies and long skulls and snouts compared to other phocids. Perhaps their most distinctive adaptation is the unique dentition that enables this species to sieve Antarctic krill. The postcanine teeth are finely divided with multiple cusps. Together with the tight fit of the upper and lower jaw, a bony protuberance near the back of the mouth completes a near-perfect sieve within which krill are trapped.[3]

Distribution and population

Crabeater seals have a continuous circumpolar distribution surrounding Antarctica, with only occasional sightings or strandings in the extreme southern coasts of Argentina, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand.[3] They spend the entire year on the pack ice zone as it advances and retreats seasonally, primarily staying within the continental shelf area in waters less than 600 m deep.[9] They colonized Antarctica during the late Miocene or early Pliocene (15-25 million years ago), at a time when the region was much warmer than today. The population is connected and fairly well mixed (panmictic), and genetic evidence does not suggest any subspecies separations.[10] A genetic survey did not detect evidence of a recent, sustained genetic bottleneck in this species,[11] which suggests that populations do not appear to have suffered a substantial and sustained decline in the recent past.

Currently, no reliable estimates of the total crabeater seal population are available. Past estimates relied on minimal opportunistic sighting and much speculation, ranging from 2 million[12] to 50-75 million individuals.[13] Genetic evidence suggests that crabeater population numbers may have increased during the Pleistocene.[14] The most recent point estimate is 7 million individuals,[15] but this, too, is considered a likely underestimate.[1] An international effort, the Antarctic Pack Ice Seal initiative, is currently underway to evaluate systematically collected survey data and obtain reliable estimates of all Antarctic seal abundances.[3]

Behavior

.jpg.webp)

Crabeater seals have a typical, serpentine gait when on ice or land, combining retractions of the foreflippers with undulations of the lumbar region.[2] This method of locomotion leaves a distinctive sinuous body track and can be extremely effective. When not subject to overheating (i.e. on cold days), speeds on land of 19–26 km/h (12–16 mph) have been recorded for short distances.[2] Satellite tracking data have resulted in conservative estimates of swimming speeds of 66 km/day and 12.7 km/h. While swimming, crabeaters have been known to engage in porpoising (leaping entirely out of the water) and spyhopping (raising the body vertically out of the water for visual inspection) behaviors.[2]

The most gregarious of the Antarctic seals, crabeaters have been observed on the ice in aggregations of up to 1,000 hauled out animals and in swimming groups of several hundred individuals, breathing and diving almost synchronously. These aggregations consist primarily of younger animals. Adults are more typically encountered alone or in small groups of up to three on the ice or in the water.[3]

Crabeater seals give birth during the Antarctic spring from September to December.[16] Rather than aggregate in reproductive rookeries, females haul out on ice to give birth singly. Adult males attend female-pup pairs until the female begins estrus one to two weeks after the pup is weaned before mating. Copulation has not been observed directly and presumably occurs in water. Pups are weaned in about three weeks,[17] at which time they are also beginning to molt into a subadult coat similar to the adult pelage.[2]

Curiously, crabeater seals have been known to wander further inland than any other pinniped. Carcasses have been found over 100 km from the water and over 1000 m above sea level, where they can be mummified in the dry, cold air and conserved for centuries.[18]

Ecology

Diet

Despite its name, the crabeater seal does not feed on crabs (the few crab species in its range are mostly found in very deep water[19]). Rather, it is a specialist predator on Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba), which comprise over 90% of the diet.[2] Their high abundance is a testament to the extreme success of Antarctic krill, the single species with the greatest biomass on the planet.[20] There is little seasonality in their prey preference, but they may target adult and male krill.[2] Other prey items include cephalopods and diverse Antarctic fish species.[2] Although the crabeater seal is sympatric with the other Antarctic seal species (Weddell, Ross and leopard seals), the specialization on krill minimizes interspecific food competition. Among krill-feeding whales, only blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus) and minke whales (B. acutorostrata) extend their range as far south as the pack ice where the crabeater seals are most frequent.[2]

While no reliable historical population estimates have been done, population models suggest crabeater seal populations may have increased at rates up to 9% a year in the 20th century, due to the removal of large baleen whales (especially the blue whale) during the period of industrial whaling and the subsequent explosion in krill biomass and removal of important competitive forces.[21]

Predation

_9.jpg.webp)

Young crabeater seals experience significant predation by leopard seals. Indeed, first-year mortality is exceedingly high, possibly reaching 80%, and up to 78% of crabeaters that survive through their first year have injuries and scars from leopard seal attacks.[1] Long scars and sets of parallel scars, visible on the otherwise pale and relatively unmarked pelage of crabeaters, are present on nearly all young seals. The incidence of visible scars falls off significantly after the first year, suggesting leopard seals primarily target the young of the year.[22] The high predation pressure has clear impacts on the demography and life history of crabeater seals, and has likely had an important role in shaping social behaviors, including aggregation of subadults.[2]

Predation by killer whales (Orcinus orca) is poorly documented, though all ages are hunted.[23] While most predation occurs in the water, coordinated attacks by groups of killer whales creating a wave to wash the hauled-out seal off floating ice have been observed.[24] Orca packs generally pursue other seals, however, as crabeaters are known to be a tenacious species that make themselves more trouble to catch than they're worth.

Gallery

See also

- Leopard seal (Hydrurga leptonyx)

- Ross seal (Ommatophoca rossii)

- Weddell seal (Leptonychotes weddellii)

References

- Hückstädt, L. (2015). "Lobodon carcinophaga". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T12246A45226918. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T12246A45226918.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- Adam, P.J. (2005). "Lobodon carcinophaga". Mammalian Species. 772: 1–14. doi:10.1644/1545-1410(2005)772[0001:lc]2.0.co;2. S2CID 198968561.

- Bengtson, J. A. (2002). "Crabeater seal Lobodon carcinophaga". In Perrin, W. F.; Wursig, B.; Thiewissen, J. G. M. (eds.). Encyclopedia of marine mammals. London, UK: Academic Press. pp. 290–292.

- Fyler, C.A.; Reeder, T.W.; Berta, A.; Antonelis, G.; Aguilar, A.; Androukaki (2005). "Historical biogeography and phylogeny of monachine seals (Pinnipedia: Phocidae) based on mitochondrial and nuclear DNA data". Journal of Biogeography. 32 (7): 1267–1279. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2005.01281.x. S2CID 15187438.

- Laws, R.; Baird, A.; Bryden, M. (2003). "Size and growth of the crabeater seal Lobodon carcinophagus (Mammalia: Carnivora)". Journal of Zoology. 259 (1): 103–108. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.516.3568. doi:10.1017/s0952836902003072.

- Curtis, Caitlin; Stewart, Brent S.; Karl, Stephen A. (2007-05-01). "Sexing Pinnipeds with ZFX and ZFY Loci". Journal of Heredity. 98 (3): 280–285. doi:10.1093/jhered/esm023. ISSN 0022-1503. PMID 17548861.

- Archived 2014-03-03 at Archive-It (2011).

- Shaughnessy, P.; Kerry, K. (2006). "Crabeater seals Lobodon carcinophagus during the breeding season: observations on five groups near Enderby Land, Antarctica". Marine Mammal Science. 5 (1): 68–77. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1989.tb00214.x.

- Burns, J., Costa, D., Fedak, M., Hindell, M., Bradshaw, C., Gales, N., McDonald, B., Trumble, S. & Crocker, D. (2004). Winter habitat use and foraging behavior of crabeater seals along the Western Antarctic Peninsula. Deep-Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography 51 (17-19), 2279-2303.

- Davis C, Stirling I, Strobeck C (2000) Genetic diversity of Antarctic pack ice seals in relation to life history characteristics. In: Antarctic Ecosystems: Models for Wider Ecological Understanding (eds Davison W, Howard-Williams C, Broady P), pp. 56-62. The Caxton Press, Christchurch, New Zealand.

- Curtis, Caitlin; Stewart, Brent S.; Karl, Stephen A. (2011-07-07). "Genetically effective population sizes of Antarctic seals estimated from nuclear genes". Conservation Genetics. 12 (6): 1435–1446. doi:10.1007/s10592-011-0241-x. ISSN 1566-0621. S2CID 732351.

- Scheffer, V. B. (1958). Seals, sea lions and walruses: A review of the Pinnipedia. Stanford University Press, Stanford, USA.

- Erickson, A. W., Siniff, D. B., Cline, D. R. and Hofman, R. J. (1971). Distributional ecology of Antarctic seals. In: G. Deacon (ed.), Symposium on Antarctic Ice and Water Masses, pp. 55-76. Sci. Comm. Antarct Res., Cambridge, UK.

- Curtis, Caitlin; Stewart, Brent S; Karl, Stephen A (2009). "Pleistocene population expansions of Antarctic seals". Molecular Ecology. 18 (10): 2112–2121. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04166.x. ISSN 1365-294X. PMID 19344354. S2CID 5323435.

- Erickson, A. W. and Hanson, M. B. (1990). Continental estimates and population trends of antarctic ice seals. In: K. R. Kerry and G. Hempel (eds), Antarctic Ecosystems. Ecological change and conservation, pp. 253-264. Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg, Germany.

- Southwell, C.; Kerry, K.; Ensor, P.; Woehler, E. J.; Rogers, T. (2003). "The timing of pupping by pack-ice seals in East Antarctica". Polar Biology. 26 (10): 648–652. doi:10.1007/s00300-003-0534-8. S2CID 7565646.

- Southwell, C.; Paxton, C. G. M.; Borchers, D.; Boveng, P.; de la Mare, W. (2008). "Taking account of dependent species in management of the Southern Ocean krill fishery: estimating crabeater seal abundance off east Antarctica". Journal of Applied Ecology. 45 (2): 622–631. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2664.2007.01399.x.

- Stirling, I.; Kooyman, G.L. (1971). "The crabeater seal (Lobodon carcinophagus) in McMurdo Sound, Antarctica, and the origin of the mummified seals". Journal of Mammalogy. 52 (1): 175–180. doi:10.2307/1378440. JSTOR 1378440.

- H.J. Griffiths; R.J. Whittle; S.J. Roberts; M. Belchier; K. Linse (2013). "Antarctic Crabs: Invasive or Endurance?". PLOS ONE. 8 (7): e66981. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...866981G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0066981. PMC 3700924. PMID 23843974.

- Nicol, S.; Endo, Y. (1997). Fisheries Technical Paper 367: Krill Fisheries of the World. FAO.

- Mori, M.; Butterworth, D. (2006). "A first step towards modelling the krill-predator dynamics of the Antarctic ecosystem". CCAMLR Science. 13: 217–277.

- Siniff, D.B.; Bengston, J.L. (1977). "Observations and hypotheses concerning the interactions about crabeater seals, leopard seals and killer whales". Journal of Mammalogy. 58 (3): 414–416. doi:10.2307/1379341. JSTOR 1379341.

- Siniff, D. B. (1991). "An overview of the ecology of Antarctic seals". American Zoologist. 31: 143–149. doi:10.1093/icb/31.1.143.

- Smith, T. G.; Siniff, D. B.; Reichle, R.; Stone, S. (1981). "Coordinated behavior of killer whales (Orcinus orca) hunting a crabeater seal, Lobodon carcinophagus". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 59 (6): 1185–1189. doi:10.1139/z81-167.

_7.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)