Cyclohexane

Cyclohexane is a cycloalkane with the molecular formula C6H12. Cyclohexane is non-polar. Cyclohexane is a colorless, flammable liquid with a distinctive detergent-like odor, reminiscent of cleaning products (in which it is sometimes used). Cyclohexane is mainly used for the industrial production of adipic acid and caprolactam, which are precursors to nylon.[5]

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Cyclohexane[1] | |||

| Other names

Hexanaphthene (archaic)[2] | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol) |

|||

| 3DMet | |||

Beilstein Reference |

1900225 | ||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| DrugBank | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.003.461 | ||

Gmelin Reference |

1662 | ||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID |

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 1145 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|||

InChI

| |||

SMILES

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C6H12 | |||

| Molar mass | 84.162 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Colorless liquid | ||

| Odor | Sweet, gasoline-like | ||

| Density | 0.7739 g/mL, liquid; Density = 0.996 g/mL, solid | ||

| Melting point | 6.47 °C (43.65 °F; 279.62 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 80.74 °C (177.33 °F; 353.89 K) | ||

Solubility in water |

Immiscible | ||

| Solubility | Soluble in ether, alcohol, acetone | ||

| Vapor pressure | 78 mmHg (20 °C)[3] | ||

| −68.13·10−6 cm3/mol | |||

Refractive index (nD) |

1.42662 | ||

| Viscosity | 1.02 cP at 17 °C | ||

| Thermochemistry | |||

Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−156 kJ/mol | ||

Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) |

−3920 kJ/mol | ||

| Hazards | |||

| GHS labelling: | |||

Pictograms |

| ||

Signal word |

Danger | ||

Hazard statements |

H225, H304, H315, H336 | ||

Precautionary statements |

P210, P233, P240, P241, P242, P243, P261, P264, P271, P273, P280, P301+P310, P302+P352, P303+P361+P353, P304+P340, P312, P321, P331, P332+P313, P362, P370+P378, P391, P403+P233, P403+P235, P405, P501 | ||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | −20 °C (−4 °F; 253 K) | ||

Autoignition temperature |

245 °C (473 °F; 518 K) | ||

| Explosive limits | 1.3–8%[3] | ||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LD50 (median dose) |

12705 mg/kg (rat, oral) 813 mg/kg (mouse, oral)[4] | ||

LCLo (lowest published) |

17,142 ppm (mouse, 2 h) 26,600 ppm (rabbit, 1 h)[4] | ||

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |||

PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 300 ppm (1050 mg/m3)[3] | ||

REL (Recommended) |

TWA 300 ppm (1050 mg/m3)[3] | ||

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

1300 ppm[3] | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related cycloalkanes |

Cyclopentane Cycloheptane | ||

Related compounds |

Cyclohexene Benzene | ||

| Supplementary data page | |||

| Cyclohexane (data page) | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |||

Cyclohexyl (C6H11) is the alkyl substituent of cyclohexane and is abbreviated Cy.[6]

Production

Modern

On an industrial scale, cyclohexane is produced by hydrogenation of benzene in the presence of a Raney nickel catalyst.[7] Producers of cyclohexane account for approximately 11.4% of global demand for benzene.[8] The reaction is highly exothermic, with ΔH(500 K) = -216.37 kJ/mol. Dehydrogenation commenced noticeably above 300 °C, reflecting the favorable entropy for dehydrogenation.[9]

Early

Unlike benzene, cyclohexane is not found in natural resources such as coal. For this reason, early investigators synthesized their cyclohexane samples.[10]

Failure

- In 1867 Marcellin Berthelot reduced benzene with hydroiodic acid at elevated temperatures.[11][12]

- In 1870, Adolf von Baeyer repeated the reaction[13] and pronounced the same reaction product "hexahydrobenzene"

- in 1890 Vladimir Markovnikov believed he was able to distill the same compound from Caucasus petroleum, calling his concoction "hexanaphtene".

Surprisingly, their cyclohexanes boiled higher by 10 °C than either hexahydrobenzene or hexanaphthene, but this riddle was solved in 1895 by Markovnikov, N.M. Kishner, and Nikolay Zelinsky when they reassigned "hexahydrobenzene" and "hexanaphtene" as methylcyclopentane, the result of an unexpected rearrangement reaction.

Success

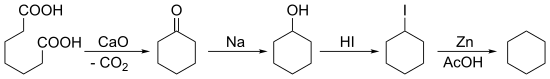

In 1894, Baeyer synthesized cyclohexane starting with a ketonization of pimelic acid followed by multiple reductions:

In the same year, E. Haworth and W.H. Perkin Jr. (1860–1929) prepared it via a Wurtz reaction of 1,6-dibromohexane.

Reactions and uses

Although rather unreactive, cyclohexane undergoes catalytic oxidation to produce cyclohexanone and cyclohexanol. The cyclohexanone–cyclohexanol mixture, called "KA oil", is a raw material for adipic acid and caprolactam, precursors to nylon. Several million kilograms of cyclohexanone and cyclohexanol are produced annually.[9]

It is used as a solvent in some brands of correction fluid. Cyclohexane is sometimes used as a non-polar organic solvent, although n-hexane is more widely used for this purpose. It is frequently used as a recrystallization solvent, as many organic compounds exhibit good solubility in hot cyclohexane and poor solubility at low temperatures.

Cyclohexane is also used for calibration of differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) instruments, because of a convenient crystal-crystal transition at −87.1 °C.[14]

Cyclohexane vapor is used in vacuum carburizing furnaces, in heat treating equipment manufacture.

Conformation

The 6-vertex edge ring does not conform to the shape of a perfect hexagon. The conformation of a flat 2D planar hexagon has considerable angle strain because its bonds are not 109.5 degrees; the torsional strain would also be considerable because all of the bonds would be eclipsed bonds. Therefore, to reduce torsional strain, cyclohexane adopts a three-dimensional structure known as the chair conformation, which rapidly interconvert at room temperature via a process known as a chair flip. During the chair flip, there are three other intermediate conformations that are encountered: the half-chair, which is the most unstable conformation, the more stable boat conformation, and the twist-boat, which is more stable than the boat but still much less stable than the chair. The chair and twist-boat are energy minima and are therefore conformers, while the half-chair and the boat are transition states and represent energy maxima. The idea that the chair conformation is the most stable structure for cyclohexane was first proposed as early as 1890 by Hermann Sachse, but only gained widespread acceptance much later. The new conformation puts the carbons at an angle of 109.5°. Half of the hydrogens are in the plane of the ring (equatorial) while the other half are perpendicular to the plane (axial). This conformation allows for the most stable structure of cyclohexane. Another conformation of cyclohexane exists, known as boat conformation, but it interconverts to the slightly more stable chair formation. If cyclohexane is mono-substituted with a large substituent, then the substituent will most likely be found attached in an equatorial position, as this is the slightly more stable conformation.

Cyclohexane has the lowest angle and torsional strain of all the cycloalkanes; as a result cyclohexane has been deemed a 0 in total ring strain.

Solid phases

Cyclohexane has two crystalline phases. The high-temperature phase I, stable between 186 K and the melting point 280 K, is a plastic crystal, which means the molecules retain some rotational degree of freedom. The low-temperature (below 186 K) phase II is ordered. Two other low-temperature (metastable) phases III and IV have been obtained by application of moderate pressures above 30 MPa, where phase IV appears exclusively in deuterated cyclohexane (application of pressure increases the values of all transition temperatures).[15]

| No | Symmetry | Space group | a (Å) | b (Å) | c (Å) | Z | T (K) | P (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Cubic | Fm3m | 8.61 | 4 | 195 | 0.1 | ||

| II | Monoclinic | C2/c | 11.23 | 6.44 | 8.20 | 4 | 115 | 0.1 |

| III | Orthorhombic | Pmnn | 6.54 | 7.95 | 5.29 | 2 | 235 | 30 |

| IV | Monoclinic | P12(1)/n1 | 6.50 | 7.64 | 5.51 | 4 | 160 | 37 |

Here Z is the number structure units per unit cell; the unit cell constants a, b and c were measured at the given temperature T and pressure P.

See also

- The Flixborough disaster, a major industrial accident caused by an explosion of cyclohexane.

- Hexane

- Ring flip

- Cyclohexane (data page)

References

- "Front Matter". Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry : IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013 (Blue Book). Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry. 2014. pp. P001–P004. doi:10.1039/9781849733069-FP001. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

- Hexanaphthene Archived 2018-02-12 at the Wayback Machine, dictionary.com

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0163". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- "Cyclohexane". Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- Campbell, M. Larry (2011). "Cyclohexane". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a08_209.pub2. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- "Standard Abbreviations and Acronyms" (PDF). The Journal of Organic Chemistry.

- Fred Fan Zhang, Thomas van Rijnman, Ji Soo Kim, Allen Cheng "On Present Methods of Hydrogenation of Aromatic Compounds, 1945 to Present Day" Lunds Tekniska Högskola 2008

- Ceresana. "Benzene - Study: Market, Analysis, Trends 2021 - Ceresana". www.ceresana.com. Archived from the original on 21 December 2017. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- Michael Tuttle Musser (2005). "Cyclohexanol and Cyclohexanone". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a08_217. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- Warnhoff, E. W. (1996). "The Curiously Intertwined Histories of Benzene and Cyclohexane". J. Chem. Educ. 73 (6): 494. Bibcode:1996JChEd..73..494W. doi:10.1021/ed073p494.

- Bertholet (1867) "Nouvelles applications des méthodes de réduction en chimie organique" (New applications of reduction methods in organic chemistry), Bulletin de la Société chimique de Paris, series 2, 7 : 53-65.

- Bertholet (1868) "Méthode universelle pour réduire et saturer d'hydrogène les composés organiques" (Universal method for reducing and saturating organic compounds with hydrogen), Bulletin de la Société chimique de Paris, series 2, 9 : 8-31. From page 17: "En effet, la benzine, chauffée à 280° pendant 24 heures avec 80 fois son poids d'une solution aqueuse saturée à froid d'acide iodhydrique, se change à peu près entièrement en hydrure d'hexylène, C12H14, en fixant 4 fois son volume d'hydrogène: C12H6 + 4H2 = C12H14 … Le nouveau carbure formé par la benzine est un corps unique et défini: il bout à 69°, et offre toutes les propriétés et la composition de l'hydrure d'hexylène extrait des pétroles." (In effect, benzene, heated to 280° for 24 hours with 80 times its weight of an aqueous solution of cold saturated hydroiodic acid, is changed almost entirely into hydride of hexylene, C12H14, [Note: this formula for hexane (C6H14) is wrong because chemists at that time used the incorrect atomic mass for carbon.] by fixing [i.e., combining with] 4 times its volume of hydrogen: C12H6 + 4H2 = C12H14 … The new carbon compound formed by benzene is a unique and well-defined substance: it boils at 69° and presents all the properties and the composition of hydride of hexylene extracted from oil.)

- Adolf Baeyer (1870) "Ueber die Reduction aromatischer Kohlenwasserstoffe durch Jodphosphonium" (On the reduction of aromatic compound by phosphonium iodide [H4IP]), Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie, 155 : 266-281. From page 279: "Bei der Reduction mit Natriumamalgam oder Jodphosphonium addiren sich im höchsten Falle sechs Atome Wasserstoff, und es entstehen Abkömmlinge, die sich von einem Kohlenwasserstoff C6H12 ableiten. Dieser Kohlenwasserstoff ist aller Wahrscheinlichkeit nach ein geschlossener Ring, da seine Derivate, das Hexahydromesitylen und Hexahydromellithsäure, mit Leichtigkeit wieder in Benzolabkömmlinge übergeführt werden können." (During the reduction [of benzene] with sodium amalgam or phosphonium iodide, six atoms of hydrogen are added in the extreme case, and there arise derivatives, which derive from a hydrocarbon C6H12. This hydrocarbon is in all probability a closed ring, since its derivatives — hexahydromesitylene [1,3,5 - trimethyl cyclohexane] and hexahydromellithic acid [cyclohexane-1,2,3,4,5,6-hexacarboxylic acid] — can be converted with ease again into benzene derivatives.)

- Price, D. M. (1995). "Temperature Calibration of Differential Scanning Calorimeters". Journal of Thermal Analysis. 45 (6): 1285–1296. doi:10.1007/BF02547423.

- Mayer, J.; Urban, S.; Habrylo, S.; Holderna, K.; Natkaniec, I.; Würflinger, A.; Zajac, W. (1991). "Neutron Scattering Studies of C6H12 and C6D12 Cyclohexane under High Pressure". Physica Status Solidi B. 166 (2): 381. Bibcode:1991PSSBR.166..381M. doi:10.1002/pssb.2221660207.

External links

- International Chemical Safety Card 0242

- National Pollutant Inventory – Cyclohexane fact sheet

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

- Cyclohexane@3Dchem

- Hermann Sachse and the first suggestion of a chair conformation.

- NLM Hazardous Substances Databank – Cyclohexane

- Methanol Discovered in Space

- Calculation of vapor pressure, liquid density, dynamic liquid viscosity, surface tension of cyclohexane

- Cyclohexane production process flowsheet, benzene hydrogenation technique