Dayak people

The Dayak (/ˈdaɪ.ək/ (![]() listen); older spelling: Dajak) or Dyak or Dayuh are one of the native groups of Borneo.[4] It is a loose term for over 200 riverine and hill-dwelling ethnic groups, located principally in the central and southern interior of Borneo, each with its own dialect, customs, laws, territory, and culture, although common distinguishing traits are readily identifiable. Dayak languages are categorised as part of the Austronesian languages. The Dayak were animist (Kaharingan and Folk Hindus) in belief; however, since the 19th century there has been mass conversion to Christianity as well as Islam due to the spreading of Abrahamic religions.[5]

listen); older spelling: Dajak) or Dyak or Dayuh are one of the native groups of Borneo.[4] It is a loose term for over 200 riverine and hill-dwelling ethnic groups, located principally in the central and southern interior of Borneo, each with its own dialect, customs, laws, territory, and culture, although common distinguishing traits are readily identifiable. Dayak languages are categorised as part of the Austronesian languages. The Dayak were animist (Kaharingan and Folk Hindus) in belief; however, since the 19th century there has been mass conversion to Christianity as well as Islam due to the spreading of Abrahamic religions.[5]

Dayak Dyak | |

|---|---|

Dayak chief as seen holding a spear and a Klebit Bok shield. | |

| Total population | |

| c. 4.6 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Borneo: | |

| c. 3,009,494[1] | |

| c. 1,582,862[2] | |

| Languages | |

| Malayo-Polynesian languages Predominantly Dayak languages Ngaju • Iban • Klemantan • Kayan • Ot Danum • Barito • Bakumpai • Ma'anyan, • Murut • etc. Also Indonesian and Malay languages Berau Malay • Kutai Malay • Mempawah • Sarawak Malay, etc. | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Christianity (Protestantism, Catholic) (63.5%) Islam (Sunni) (30.6%) Minorities Kaharingan (5%) and Others (i.e. Animism) (1%)[3] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Austronesian peoples Banjarese • Bornean Malays • Rejang • Malagasy, etc. | |

Etymology

It is commonly assumed that the name originates from the Bruneian and Melanau word for “interior people”, without any reference to an exact ethnic group. The term was adopted by Dutch and German authors as an umbrella term for any non-Muslim natives of Borneo. Thus, the difference between Dayaks and non-Dayaks natives could be understood as a religious distinction. English writers disapproved the classification made by the Dutch and Germans, with James Brooke preferring to use the term Dayak for only two distinct groups, the Land (Bidayuh) and Sea Dayaks (Iban).[6]

The Dutch practice since the 19th century has eventually gained traction in Indonesia, as a definition to all indigenous non-Muslim tribes in the island until today. In Malaysia, the term Dayak generally remains as an almost exclusively reference to the Iban (previously referred as Sea Dayaks) and Bidayuh (known as Land Dayak in the past).[7]

Ethnicity and languages

Dayaks do not speak just one language.[8] Their indigenous languages belong to different subgroups of the Malayo-Polynesian languages, such as Land Dayak, Malayic, Sabahan, and Barito languages.[9][10] Nowadays most Dayaks are bilingual, in addition to their native language, are well-versed in Indonesian and Malay, depending their country of origin. Many of Borneo's languages are endemic (which means they are spoken nowhere else). This cultural and linguistic diversity parallels the high biodiversity and related traditional knowledge of Borneo.

It is estimated that around 170 languages and dialects are spoken on the island and some by just a few hundred people, thus posing a serious risk to the future of those languages and related heritage.

In 1954, Tjilik Riwut classified the various Dayak groups into 18 tribes throughout the island of Borneo, with 403 sub-tribes according to their respective native languages, customs, and cultures. However, he did not specify the name of the sub-tribes in his publication:[11]

| Cluster | Tribe | Number of sub-tribes | Regions with significant population[12] |

|---|---|---|---|

| I. Ngaju |

Ngaju |

53 |

Central-Southern Borneo |

| II. Apukayan |

Kenyah |

24 |

Eastern Borneo |

| III. Iban/Sea Dayaks |

Iban |

11 |

Northwestern inland and coastal Borneo |

| IV. Klemantan/Land Dayaks |

Klemantan |

47 |

Northwestern outback Borneo |

| V. Punan |

Basap |

20 |

Central-East Borneo |

| VI. Murut |

Idaan/Dusun |

6 |

Northern Borneo |

| VII. Ot Danum |

Ot Danum |

61 |

Central-Southern Borneo |

Religion

Religion of Dayak People

Hinduism

Before colonialism some Dayak people practiced Hinduism, likely due to influence from the Majapahit empire, the practice and presence of Hinduism can be seen as early as 960 A.D., when Hindu ornaments dating to this time were found in the Sarawak river. Other evidence of the Hindu religion being practiced by the Dayak people were the presence of several idols, including one of Nandi, the name of their deity, Jewata, from Javanese Hinduism, the belief in the sacredness of the cow, loanwords from Hinduism such as "Padma" for a plant and "Sakara" for a constellation, and the practice of cremation of their dead.[13] Some of the earliest kingdoms and states in Borneo established by the Dayaks were known to practice Hinduism, including Wijayapura,[14] Kutai,[15] and Bangkule Sultankng.[16]

Kaharingan

In Indonesia, the Dayak indigenous religion has been given the name Kaharingan, and may be said to be a form of animism. In 1945, during the Japanese occupation, the Japanese referred to Kaharingan as the religion of the Dayak people. During the New Order in the Suharto regime in 1980, the Kaharingan is registered as a form of Hinduism in Indonesia, as the Indonesian state only recognises 6 forms of religion i.e. Islam, Protestantism, Roman Catholicism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Confucianism respectively. The integration of Kaharingan with Hinduism is not due to the similarities in the theological system, but due to the fact that Kaharingan is the oldest belief in Kalimantan. Unlike the development in Indonesian Kalimantan, Kaharingan is not used as a religious designation in Malaysian and Brunei, thus the traditional Dayak belief system is categorized as a form of folk animism or paganism outside of the Indonesian border.[17]

The best and still unsurpassed study of traditional Dayak religion in Kalimantan is that of Hans Scharer, Ngaju Religion: The Conception of God among a South Borneo People; translated by Rodney Needham (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1963). The practice of Kaharingan differs from group to group, but shamans, specialists in ecstatic flight to other spheres, are central to Dayak religion and serve to bring together the various realms of Heaven (Upper-world) and earth, and even Under-world, for example healing the sick by retrieving their souls which are journeying on their way to the Upper-world land of the dead, accompanying and protecting the soul of a dead person on the way to their proper place in the Upper-world, presiding over annual renewal and agricultural regeneration festivals, etc.[18] Death rituals are most elaborate when a noble (kamang) dies.[19]

Christianity

Over the last two centuries, many Dayaks have converted to Christianity, making them the majority of Christians in Borneo, abandoning certain cultural rites and traditional practices in the process. Christianity was introduced by European missionaries in Borneo by Rheinische Missionsgesellschaft (later followed up by the Basler Mission).[20] Religious differences between Muslim and Christian natives of Borneo has led, at various times, to communal tensions.[21] Relations, however between all religious groups are generally good.

Islam

Traditionally, in many parts of Borneo, embracing Muslim faith is equated with Malayisation (Indonesian/Malay: masuk Melayu), i.e. assimilation into the broader Malay ethnicity. There are, however, several Dayak sub-ethnicities (mainly in Central Kalimantan) which predominantly adhere to Islam, but nevertheless self-identify as Dayaks. These include e.g. the Bakumpai people, who converted to Islam in the 19th century, but still have strong linguistic and cultural ties to the Ngaju people. They have adopted a positive attitude towards the label "Dayak" and self-identify as Muslim Dayaks.[22]

Society and customs

Economic activities

Historically, most of the Dayak people are swidden cultivators who supplement their incomes by seeking forest products, both for subsistence (ferns, medicinal plants, fibers, and timber) and for sale; by fishing and hunting and by periodic wage labor.[23] Presently, many modern-day Dayaks are also actively engaged in many contemporary economic activities, especially in the urban areas of Borneo.[24]

Toplessness

In the Indonesian region, toplessness was the norm among the Dayak people, Javanese, and the Balinese people of Indonesia before the introduction of Islam and contact with Western cultures. In Javanese and Balinese societies, women worked or rested comfortably topless. Among the Dayak, only big breasted women or married women with sagging breasts cover their breasts because they interfered with their work. Once shirts are available, toplessness has been abandoned.[25]

Longhouses

In the traditional Dayak society, the long house is regarded as the heart of the community, it functioned as the village, as well as the societal architectural expression. These large building, sometimes exceeds 200 meters long, may have divided into independent household apartments. The building is also equipped with communal areas for cooking, ceremonies, socializing and blacksmithing.

The superstructure is not solely revolves on architecture and design. It is a part of the Dayak traditional political entity and administrative system. Thus, culturally the people residing in the longhouse are governed by the customs and traditions of the longhouse.[26]

Metal-working

Metal-working is elaborately developed in making mandaus (machetes – parang in Malay and Indonesian). The blade is made of softer iron, to prevent breakage, with a narrow strip of a harder iron wedged into a slot in the cutting edge for sharpness in a process called ngamboh (iron-smithing).

In headhunting, it was necessary to be able to draw the parang quickly. For this purpose, the mandau is fairly short, which also better serves the purpose of trail cutting in dense forests. It is holstered with the cutting edge facing upwards and at that side, there is an upward protrusion on the handle, so it can be drawn very quickly with the side of the hand without having to reach over and grasp the handle first. The hand can then grasp the handle while it is being drawn. The combination of these three factors (short, cutting edge up and protrusion) makes for an extremely fast drawing-action.

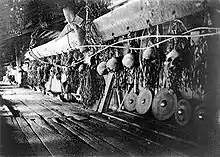

Headhunting and peacemaking

In the past, the Dayaks were feared for their ancient tradition of headhunting practices (the ritual is also known as Ngayau by the Dayaks).

Among the most prominent legacy during the colonial rule in the Dutch Borneo (present-day Kalimantan) is the Tumbang Anoi Agreement held in 1874 in Damang Batu, Central Kalimantan (the seat of the Kahayan Dayaks). It is a formal meeting that gathered all the Dayak tribes in Kalimantan for a peace resolution. In the meeting that is reputed taken several months, the Dayak people throughout the Kalimantan agreed to end the headhunting tradition as it believed the tradition caused conflict and tension between various Dayak groups. The meeting ended with a peace resolution by the Dayak people.[27]

Subsequently, the headhunting began to surface again in the mid-1940s, when the Allied powers encouraged the practice against the Japanese occupation of Borneo.[28] It also slightly surged in the late 1960s when the Indonesian government encouraged Dayaks to purge the Chinese from interior Kalimantan who were suspected of supporting communism in mainland China and also in the late 1990s when the Dayak started to attack Madurese emigrants in an explosion of ethnic violence.[29]

Military

The Dayak soldiers or trackers are regarded as equivalent in bravery to the Royal Scots or the Gurkha soldiers. The Sarawak Rangers was absorbed into the British Army as the Far East Land Forces which could be deployed anywhere in the world but upon the formation of Malaysia in 1963, it formed the basis of the present day Royal Ranger Regiment.[30]

While in Indonesia, Tjilik Riwut was remembered as he led the first airborne operation by Indonesian National Armed Forces on 17 October 1947. The team was known as MN 1001, with 17 October celebrated annually as the anniversary date for the Indonesian Air Force Paskhas, which traces its origins to that pioneer paratroop operation in Borneo.[31]

Gallery

Ma'anyan women during Keang Ethnic Festival

Ma'anyan women during Keang Ethnic Festival Colorfull wall art by the Kenyah people

Colorfull wall art by the Kenyah people An Iban (Sea Dayak) man from Sarawak in his warrior costume

An Iban (Sea Dayak) man from Sarawak in his warrior costume A Baluk in Jagoi Babang, West Kalimantan, the ceremonial hall for Bidayuh (Land Dayak) people

A Baluk in Jagoi Babang, West Kalimantan, the ceremonial hall for Bidayuh (Land Dayak) people A Punan girl, some Dayak tribes are known for their elongated earlobes formed by iron earrings (1931-1932)

A Punan girl, some Dayak tribes are known for their elongated earlobes formed by iron earrings (1931-1932).jpg.webp) Lansaran, a Murut traditional trampoline game

Lansaran, a Murut traditional trampoline game A tattooed Dayak man from Central Borneo, possibly of Ot Danum origin (1880-1920)

A tattooed Dayak man from Central Borneo, possibly of Ot Danum origin (1880-1920)

See also

- List of Dayak people

- Bornean traditional tattooing

References

- "Jumlah dan Persentase Penduduk menurut Kelompok Suku Bangsa" (PDF). media.neliti.com. Kewarganegaraan, suku bangsa, agama dan bahasa sehari-hari penduduk Indonesia. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- "Population Distribution and Demography" (PDF). Malaysian Department of Statistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2013.

- Ananta, Aris; Arifin, Evi; Hasbullah, M.; Handayani, Nur; Pramono, Wahyu (2015). Demography of Indonesia's Ethnicity. Singapore: ISEAS Publishing. p. 272. ISBN 978-981-4519-87-8. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- "Report for ISO 639 code: day". Ethnologue: Countries of the World. Archived from the original on 1 October 2007.

- Chalmers, Ian (2006). "The Dynamics of Conversion: the Islamisation of the Dayak peoples of Central Kalimantan" (PDF). Asian Studies Association of Australia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2014. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- Tillotson (1994). "Who invented the Dayaks? : historical case studies in art, material culture and ethnic identity from Borneo". Open Research Library. Australian National University. doi:10.25911/5d70f0cb47d77. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- "Dayak". Britanicca. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- Avé, J. B. (1972). "Kalimantan Dyaks". In LeBar, Frank M. (ed.). Ethnic Groups of Insular Southeast Asia, Volume 1: Indonesia, Andaman Islands, and Madagascar. New Haven: Human Relations Area Files Press. pp. 185–187. ISBN 978-0-87536-403-2.

- Adelaar, K. Alexander (1995). Bellwood, Peter; Fox. James J.; Tryon, Darrell (eds.). "Borneo as a cross-roads for comparative Austronesian linguistics" (PDF). The Austronesians: Historical and Comparative Perspectives (online ed.). Canberra, Australia: Department of Anthropology, The Australian National University: 81–102. ISBN 978-1-920942-85-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2014. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- See the language list at "Borneo Languages: Languages of Kalimantan, Indonesia and East Malaysia". Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies, Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde (KITLV). Archived from the original on 9 February 2012.

- Masri Singarimbun (1991). "Beberapa aspek kehidupan masyarakat Dayak". Humaniora. 3: 139–151. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- Masri Singaribum. "Beberapa Aspek Kehidupan Masyarakat Dayak". media.neliti. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- Baring-Gould, Sabine (1909). A History of Sarawak Under Its Two White Rajahs, 1839-1908. p. 21.

- "Kerajaan Wijayapura: Kerajaan Hindu di Utara Kalimantan Barat". www.misterpangalayo.com (in Indonesian). misterpangalayo. 2022. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- "Sejarah Kutai Martadipura, Kerajaan Hindu-Buddha Tertua di Indonesia". Kompas.com (in Indonesian). Kompas. 2022. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- "Kerajaan Mempawah: Sejarah, Pendiri, Raja-raja, dan Keruntuhan". Kompas.com (in Indonesian). Kompas. 2021. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- Baier, Martin (2007). "The Development of the Hindu Kaharingan Religion: A New Dayak Religion in Central Kalimantan". Anthropos. 102 (2): 566–570. doi:10.5771/0257-9774-2007-2-566. JSTOR 40389742.

- The most detailed study of the shamanistic ritual at funerals is by Waldemar Stöhr, Der Totenkult der Ngadju Dajak in Süd-Borneo. Mythen zum Totenkult und die Texte zum Tantolak Matei (Den Haag: Martinus Nijhoff, 1966).

- Dowling, Nancy (1992). "The Javanization of Indian Art". Indonesia. 54 (54): 117–138. doi:10.2307/3351167. hdl:1813/53986. JSTOR 3351167.

- Rahman Hakim, Arif (2003). Sejarah kota Palangka Raya. Palangka Raya: Palangka Raya : Pemerintah Kota Palangka Raya. pp. 18–20. ISBN 979-97978-0-2.

- Avé, Jan B.; King, Victor T. (1986). The People of the Weeping Forest: Tradition and Change in Borneo. Leiden, Netherlands: National Museum of Ethnology. ISBN 978-9-07131-028-7.

- Chalmers, Ian (2006). "The Dynamics of Conversion: the Islamisation of the Dayak peoples of Central Kalimantan". In Vickers, A.; Hanlon, M. (eds.). Asia Reconstructed: Proceedings of the 16th Biennial Conference of the ASAA. Wollongong, NSW: Australian National University. hdl:20.500.11937/35283. ISBN 9780958083737.

- Colfer, Carol J. Pierce; Byron, Yvonne (2001). People Managing Forests: The Links Between Human Well-Being and Sustainability. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future. ISBN 1-891853-05-8.

- Boulanger (2010). "Inventing Tradition, Inventing Modernity: Dayak Identity in Urban Sarawak". Asian Ethnicity. Taylor & Francis. 3 (2): 221–231. doi:10.1080/14631360220132745. S2CID 144515877. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- Duerr, Hans Peter (1997). Der Mythos vom Zivilisationsprozeß (in German). Vol. 4: Der Erotische Leib. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

- "Dayak Architecture and Art: The Use of Longhouse". Kaltimber. Kaltimber. 20 July 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- Robert Kenneth (26 July 2019). "Dayaks Gather to Mark Peace Treaty". New Sarawak Tribune. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- Heimannov, Judith M. (9 November 2007). "'Guests' can succeed where occupiers fail". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "The Sampit conflict – Chronology of violence in Central Kalimantan". Discover Indonesia Online. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- Robert Rizal Abdullah (2019). The Iban Trackers and Sarawak Rangers: 1948–1963. Available at https://ir.unimas.my/id/eprint/25997/1/The%20Iban%20Trackers%20and%20Sarawak%20Rangers.pdf. (Accessed on 18/01/2020)

- R.Rizky, T. Wibisono (2012). Mengenal Seni dan Budaya Indonesia (in Indonesian). Penebar CIF. p. 74. ISBN 978-9797883102.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

Further reading

- Benedict Sandin (1967). The Sea Dayaks of Borneo Before White Rajah Rule. Macmillan.

- Derek Freeman (1955). Iban Agriculture: A Report on the Shifting Cultivation of Hill Rice by the Iban of Sarawak. H.M. Stationery Office.

- Derek Freeman (1970). Report on the Iban. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Eric Hansen (1988). Stranger in the Forest: On Foot Across Borneo. Vintage Books. ISBN 9780375724954.

- Hans Schärer (2013). Ngaju Religion: The Conception of God among a South Borneo People. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9789401193467.

- Jean Yves Domalain (1973). Panjamon: I was a Headhunter. William Morrow. ISBN 9780688000288.

- Judith M. Heimann (2009). The Airmen and the Headhunters: A True Story of Lost Soldiers, Heroic Tribesmen and the Unlikeliest Rescue of World War II. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 9780547416069.

- Norma R. Youngberg (2000). The Queen's Gold. TEACH Services. ISBN 9781572581555.

- Peter Goullart (1965). River of the White Lily: Life in Sarawak. John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-0542-9.

- Raymond Corbey (2016). Of Jars and Gongs: Two Keys to Ot Danum Dayak Cosmology. C. Zwartenkot Art Books. ISBN 9789054500162.

- St. John, Sir Spenser (1879). The life of Sir James Brooke: Rajah of Sarawak: From His Personal Papers and Correspondence. Edinburgh & London.

- Syamsuddin Haris (2005). Desentralisasi dan Otonomi Daerah: Desentralisasi, Demokratisasi & Akuntabilitas Pemerintahan Daerah. Yayasan Obor Indonesia. ISBN 9789799801418.

- Victor T King (1978). Essays on Borneo Societies. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780197134344.

External links

- Tribal peoples are fighting huge hydro-electric projects that are carving up the island's rainforest

- The J. Arthur and Edna Mouw papers at the Hoover Institution Archives focuses on the interaction of Christian missionaries with Dayak people in Borneo.

- The Airmen and the Headhunters Documentary produced by the PBS Series Secrets of the Dead