Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan,[lower-alpha 3] also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state[lower-alpha 4] and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent formation of modern Japan.[8] It encompassed the Japanese archipelago and several colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories.

Empire of Japan

| |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1868–1947 | |||||||||||

Imperial Seal

| |||||||||||

Motto:

| |||||||||||

| Anthem: (1869–1945) "Kimigayo" (君が代) | |||||||||||

.svg.png.webp) The Empire of Japan at its peak in 1942:

| |||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||

| Largest city |

| ||||||||||

| Official languages | Japanese | ||||||||||

| Recognised regional languages | |||||||||||

| Religion |

| ||||||||||

| Government | Unitary absolute monarchy (1868–1889)[7]

Unitary parliamentary semi-constitutional monarchy

| ||||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||||

• 1868–1912 | Meiji | ||||||||||

• 1912–1926 | Taishō | ||||||||||

• 1926–1947 | Shōwa | ||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||

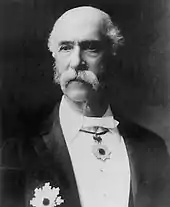

• 1885–1888 (first) | Itō Hirobumi | ||||||||||

• 1946–1947 (last) | Shigeru Yoshida | ||||||||||

| Legislature | None (rule by decree) (1868–1871) House of Peers (1871–1889) Imperial Diet (since 1889) | ||||||||||

| House of Peers (1889–1947) | |||||||||||

| House of Representatives (from 1890) | |||||||||||

| Historical era | Meiji • Taishō • Shōwa | ||||||||||

| 3 January 1868[9] | |||||||||||

• Meiji Constitution | 11 February 1889 | ||||||||||

| 25 July 1894 | |||||||||||

| 8 February 1904 | |||||||||||

| 23 August 1914 | |||||||||||

| 18 September 1931 | |||||||||||

| 7 July 1937 | |||||||||||

• Founding of the IRAA | 12 October 1940 | ||||||||||

| 7 December 1941 | |||||||||||

| 2 September 1945 | |||||||||||

| 3 May 1947[8] | |||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

| 1938[10] | 1,984,000 km2 (766,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| 1942[11] | 7,400,000 km2 (2,900,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

• 1920 | 77,700,000a | ||||||||||

• 1940 | 105,200,000b | ||||||||||

| Currency |

| ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Japan |

|---|

|

|

| Japanese Empire | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japanese name | |||||

| Kanji | 大日本帝国 | ||||

| Hiragana | だいにっぽんていこく だいにほんていこく | ||||

| Katakana | ダイニッポンテイコク ダイニホンテイコク | ||||

| Kyūjitai | 大日本帝國 | ||||

| |||||

| Japanese Empire | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japanese name | |||||

| Kyūjitai | 大日本帝國 | ||||

| Shinjitai | 大日本帝国 | ||||

| |||||

| Official Term name | |||||

| Official Term | Japanese Empire | ||||

| Literal Translation name | |||||

| Literal Translation | Imperial State of Greater Japan | ||||

Under the slogans of fukoku kyōhei[lower-alpha 5] and shokusan kōgyō,[lower-alpha 6] following the Boshin War and restoration of power to the Emperor from the Shogun, Japan underwent a period of industrialization and militarization, the Meiji Restoration, which is often regarded as the fastest modernisation of any country to date. All of these aspects contributed to Japan's emergence as a great power and the establishment of a colonial empire following the First Sino-Japanese War, the Boxer Rebellion, the Russo-Japanese War, and World War I. Economic and political turmoil in the 1920s, including the Great Depression, led to the rise of militarism, nationalism and totalitarianism as embodied in the Showa Statism ideology, eventually culminating in Japan's membership in the Axis alliance and the conquest of a large part of the Asia-Pacific in World War II.[16]

Japan's armed forces initially achieved large-scale military successes during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) and the Pacific War. However, starting from 1942, particularly after the Battles of Midway and Guadalcanal, Japan was forced to adopt a defensive stance, and the American island hopping campaign lead to the eventual loss of many of Japan's Oceanian island possessions throughout the following three years. Eventually, the Americans captured Iwo Jima and Okinawa Island, leaving the Japanese mainland unprotected and without a significant naval defense force. The U.S. forces had planned an invasion, but Japan surrendered following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the nearly simultaneous Soviet declaration of war on August 9, 1945, and subsequent invasion of Manchuria and other territories. The Pacific War officially came to a close on September 2, 1945. A period of occupation by the Allies followed. In 1947, with American involvement, a new constitution was enacted, officially bringing the Empire of Japan to an end, and Japan's Imperial Army was replaced with the Japan Self-Defense Forces. Occupation and reconstruction continued until 1952, eventually forming the current constitutional monarchy known as the State of Japan.

The Empire of Japan had three emperors, although it came to an end partway through Shōwa's reign. The emperors were given posthumous names, and the emperors are as follows: Meiji, Taisho, and Shōwa.

Terminology

The historical state is frequently referred to as the "Empire of Japan", the "Japanese Empire", or "Imperial Japan" in English. In Japanese it is referred to as Dai Nippon Teikoku (大日本帝國),[13] which translates to "Empire of Great Japan" (Dai "Great", Nippon "Japanese", Teikoku "Empire"). Teikoku is itself composed of the nouns Tei "referring to an emperor" and -koku "nation, state", literally "Imperial State" or "Imperial Realm" (compare the German Kaiserreich).

This meaning is significant in terms of geography, encompassing Japan, and its surrounding areas. The nomenclature Empire of Japan had existed since the anti-Tokugawa domains, Satsuma and Chōshū, which founded their new government during the Meiji Restoration, with the intention of forming a modern state to resist Western domination. Later the Empire emerged as a major colonial power in the world.

Due to its name in kanji characters and its flag, it was also given the exonyms "Empire of the Sun" and “Empire of the Rising Sun.”

History

Background

After two centuries, the seclusion policy, or sakoku, under the shōguns of the Edo period came to an end when the country was forced open to trade by the Convention of Kanagawa which came when Matthew C. Perry arrived in Japan in 1854. Thus, the period known as Bakumatsu began.

The following years saw increased foreign trade and interaction; commercial treaties between the Tokugawa shogunate and Western countries were signed. In large part due to the humiliating terms of these unequal treaties, the shogunate soon faced internal hostility, which materialized into a radical, xenophobic movement, the sonnō jōi (literally "Revere the Emperor, expel the barbarians").[17]

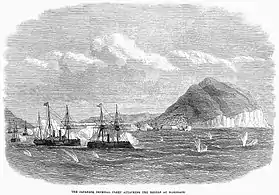

In March 1863, the Emperor issued the "order to expel barbarians." Although the shogunate had no intention of enforcing the order, it nevertheless inspired attacks against the shogunate itself and against foreigners in Japan. The Namamugi Incident during 1862 led to the murder of an Englishman, Charles Lennox Richardson, by a party of samurai from Satsuma. The British demanded reparations but were denied. While attempting to exact payment, the Royal Navy was fired on from coastal batteries near the town of Kagoshima. They responded by bombarding the port of Kagoshima in 1863. The Tokugawa government agreed to pay an indemnity for Richardson's death.[18] Shelling of foreign shipping in Shimonoseki and attacks against foreign property led to the bombardment of Shimonoseki by a multinational force in 1864.[19] The Chōshū clan also launched the failed coup known as the Kinmon incident. The Satsuma-Chōshū alliance was established in 1866 to combine their efforts to overthrow the Tokugawa bakufu. In early 1867, Emperor Kōmei died of smallpox and was replaced by his son, Crown Prince Mutsuhito (Meiji).

On November 9, 1867, Tokugawa Yoshinobu resigned from his post and authorities to the Emperor, agreeing to "be the instrument for carrying out" imperial orders,[20] leading to the end of the Tokugawa shogunate.[21][22] However, while Yoshinobu's resignation had created a nominal void at the highest level of government, his apparatus of state continued to exist. Moreover, the shogunal government, the Tokugawa family in particular, remained a prominent force in the evolving political order and retained many executive powers,[23] a prospect hard-liners from Satsuma and Chōshū found intolerable.[24]

On January 3, 1868, Satsuma-Chōshū forces seized the imperial palace in Kyoto, and the following day had the fifteen-year-old Emperor Meiji declare his own restoration to full power. Although the majority of the imperial consultative assembly was happy with the formal declaration of direct rule by the court and tended to support a continued collaboration with the Tokugawa, Saigō Takamori, leader of the Satsuma clan, threatened the assembly into abolishing the title shōgun and ordered the confiscation of Yoshinobu's lands.[lower-alpha 7]

On January 17, 1868, Yoshinobu declared "that he would not be bound by the proclamation of the Restoration and called on the court to rescind it".[26] On January 24, Yoshinobu decided to prepare an attack on Kyoto, occupied by Satsuma and Chōshū forces. This decision was prompted by his learning of a series of arson attacks in Edo, starting with the burning of the outworks of Edo Castle, the main Tokugawa residence.

Boshin War

The Boshin War (戊辰戦争, Boshin Sensō) was fought between January 1868 and May 1869. The alliance of samurai from southern and western domains and court officials had now secured the cooperation of the young Emperor Meiji, who ordered the dissolution of the two-hundred-year-old Tokugawa shogunate. Tokugawa Yoshinobu launched a military campaign to seize the emperor's court in Kyoto. However, the tide rapidly turned in favor of the smaller but relatively modernized imperial faction and resulted in defections of many daimyōs to the Imperial side. The Battle of Toba–Fushimi was a decisive victory in which a combined army from Chōshū, Tosa, and Satsuma domains defeated the Tokugawa army.[27] A series of battles were then fought in pursuit of supporters of the Shogunate; Edo surrendered to the Imperial forces and afterward, Yoshinobu personally surrendered. Yoshinobu was stripped of all his power by Emperor Meiji and most of Japan accepted the emperor's rule.

Pro-Tokugawa remnants, however, then retreated to northern Honshū (Ōuetsu Reppan Dōmei) and later to Ezo (present-day Hokkaidō), where they established the breakaway Republic of Ezo. An expeditionary force was dispatched by the new government and the Ezo Republic forces were overwhelmed. The siege of Hakodate came to an end in May 1869 and the remaining forces surrendered.[27]

Meiji era (1868–1912)

The Charter Oath was made public at the enthronement of Emperor Meiji of Japan on April 7, 1868. The Oath outlined the main aims and the course of action to be followed during Emperor Meiji's reign, setting the legal stage for Japan's modernization.[28] The Meiji leaders also aimed to boost morale and win financial support for the new government.

Japan dispatched the Iwakura Mission in 1871. The mission traveled the world in order to renegotiate the unequal treaties with the United States and European countries that Japan had been forced into during the Tokugawa shogunate, and to gather information on western social and economic systems, in order to effect the modernization of Japan. Renegotiation of the unequal treaties was universally unsuccessful, but close observation of the American and European systems inspired members on their return to bring about modernization initiatives in Japan. Japan made a territorial delimitation treaty with Russia in 1875, gaining all the Kuril islands in exchange for Sakhalin island.[29]

The Japanese government sent observers to Western countries to observe and learn their practices, and also paid "foreign advisors" in a variety of fields to come to Japan to educate the populace. For instance, the judicial system and constitution were modeled after Prussia, described by Saburō Ienaga as "an attempt to control popular thought with a blend of Confucianism and German conservatism."[30] The government also outlawed customs linked to Japan's feudal past, such as publicly displaying and wearing katana and the top knot, both of which were characteristic of the samurai class, which was abolished together with the caste system. This would later bring the Meiji government into conflict with the samurai.

Several writers, under the constant threat of assassination from their political foes, were influential in winning Japanese support for westernization. One such writer was Fukuzawa Yukichi, whose works included "Conditions in the West," "Leaving Asia", and "An Outline of a Theory of Civilization," which detailed Western society and his own philosophies. In the Meiji Restoration period, military and economic power was emphasized. Military strength became the means for national development and stability. Imperial Japan became the only non-Western world power and a major force in East Asia in about 25 years as a result of industrialization and economic development.

As writer Albrecht Fürst von Urach comments in his booklet "The Secret of Japan's Strength," published in 1942, during the Axis powers period:

The rise of Japan to a world power during the past 80 years is the greatest miracle in world history. The mighty empires of antiquity, the major political institutions of the Middle Ages and the early modern era, the Spanish Empire, the British Empire, all needed centuries to achieve their full strength. Japan's rise has been meteoric. After only 80 years, it is one of the few great powers that determine the fate of the world.[31]

Transposition in social order and cultural destruction

In the 1860s, Japan began to experience great social turmoil and rapid modernization. The feudal caste system in Japan formally ended in 1869 with the Meiji restoration. In 1871, the newly formed Meiji government issued a decree called Senmin Haishirei (賤民廃止令 Edict Abolishing Ignoble Classes) giving burakumin equal legal status. It is currently better known as the Kaihōrei (解放令 Emancipation Edict). However, the elimination of their economic monopolies over certain occupations actually led to a decline in their general living standards, while social discrimination simply continued. For example, the ban on the consumption of meat from livestock was lifted in 1871, and many former burakumin moved on to work in abattoirs and as butchers. However, slow-changing social attitudes, especially in the countryside, meant that abattoirs and workers were met with hostility from local residents. Continued ostracism as well as the decline in living standards led to former burakumin communities turning into slum areas.

In the Blood tax riots, the Japanese Meiji government brutally put down revolts by Japanese samurai angry that the traditional untouchable status of burakumin was legally revoked.

The social tension continued to grow during the Meiji period, affecting religious practices and institutions. Conversion from traditional faith was no longer legally forbidden, officials lifted the 250-year ban on Christianity, and missionaries of established Christian churches reentered Japan. The traditional syncreticism between Shinto and Buddhism ended. Losing the protection of the Japanese government which Buddhism had enjoyed for centuries, Buddhist monks faced radical difficulties in sustaining their institutions, but their activities also became less restrained by governmental policies and restrictions. As social conflicts emerged in this last decade of the Edo period, some new religious movements appeared, which were directly influenced by shamanism and Shinto.

Emperor Ogimachi issued edicts to ban Catholicism in 1565 and 1568, but to little effect. Beginning in 1587 with imperial regent Toyotomi Hideyoshi's ban on Jesuit missionaries, Christianity was repressed as a threat to national unity. Under Hideyoshi and the succeeding Tokugawa shogunate, Catholic Christianity was repressed and adherents were persecuted. After the Tokugawa shogunate banned Christianity in 1620, it ceased to exist publicly. Many Catholics went underground, becoming hidden Christians (隠れキリシタン, kakure kirishitan), while others lost their lives. After Japan was opened to foreign powers in 1853, many Christian clergymen were sent from Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox churches, though proselytism was still banned. Only after the Meiji Restoration, was Christianity re-established in Japan. Freedom of religion was introduced in 1871, giving all Christian communities the right to legal existence and preaching.

Eastern Orthodoxy was brought to Japan in the 19th century by St. Nicholas (baptized as Ivan Dmitrievich Kasatkin),[32] who was sent in 1861 by the Russian Orthodox Church to Hakodate, Hokkaidō as priest to a chapel of the Russian Consulate.[33] St. Nicholas of Japan made his own translation of the New Testament and some other religious books (Lenten Triodion, Pentecostarion, Feast Services, Book of Psalms, Irmologion) into Japanese.[34] Nicholas has since been canonized as a saint by the Patriarchate of Moscow in 1970, and is now recognized as St. Nicholas, Equal-to-the-Apostles to Japan. His commemoration day is February 16. Andronic Nikolsky, appointed the first Bishop of Kyoto and later martyred as the archbishop of Perm during the Russian Revolution, was also canonized by the Russian Orthodox Church as a Saint and Martyr in the year 2000.

Divie Bethune McCartee was the first ordained Presbyterian minister missionary to visit Japan, in 1861–1862. His gospel tract translated into Japanese was among the first Protestant literature in Japan. In 1865, McCartee moved back to Ningbo, China, but others have followed in his footsteps. There was a burst of growth of Christianity in the late 19th century when Japan re-opened its doors to the West. Protestant church growth slowed dramatically in the early 20th century under the influence of the military government during the Shōwa period.

Under the Meiji Restoration, the practices of the samurai classes, deemed feudal and unsuitable for modern times following the end of sakoku in 1853, resulted in a number of edicts intended to 'modernise' the appearance of upper class Japanese men. With the Dampatsurei Edict of 1871 issued by Emperor Meiji during the early Meiji Era, men of the samurai classes were forced to cut their hair short, effectively abandoning the chonmage (chonmage) hairstyle.[35]: 149

During the early 20th century, the government was suspicious towards a number of unauthorized religious movements and periodically made attempts to suppress them. Government suppression was especially severe from the 1930s until the early 1940s, when the growth of Japanese nationalism and State Shinto were closely linked. Under the Meiji regime lèse majesté prohibited insults against the Emperor and his Imperial House, and also against some major Shinto shrines which were believed to be tied strongly to the Emperor. The government strengthened its control over religious institutions that were considered to undermine State Shinto or nationalism.

The majority of Japanese castles were smashed and destroyed in the late 19th century in the Meiji restoration by the Japanese people and government in order to modernize and westernize Japan and break from their past feudal era of the Daimyo and Shoguns. It was only due to the 1964 Summer Olympics in Japan that cheap concrete replicas of those castles were built for tourists.[36][37][38] The vast majority of castles in Japan today are new replicas made out of concrete.[39][40][41] In 1959 a concrete keep was built for Nagoya castle.[42]

During the Meiji restoration's Shinbutsu bunri, tens of thousands of Japanese Buddhist religious idols and temples were smashed and destroyed.[43][44] Many statues still lie in ruins. Replica temples were rebuilt with concrete. Japan then closed and shut done tens of thousands of traditional old Shinto shrines in the Shrine Consolidation Policy and the Meiji government built the new modern 15 shrines of the Kenmu restoration as a political move to link the Meiji restoration to the Kenmu restoration for their new State Shinto cult.

Japanese had to look at old paintings in order to find out what the Horyuji temple used to look like when they rebuilt it. The rebuilding was originally planned for the Shōwa era.[45]

The Japanese used mostly concrete in 1934 to rebuild the Togetsukyo Bridge, unlike the original destroyed wooden version of the bridge from 836.[46]

Political reform

The idea of a written constitution had been a subject of heated debate within and outside of the government since the beginnings of the Meiji government. The conservative Meiji oligarchy viewed anything resembling democracy or republicanism with suspicion and trepidation, and favored a gradualist approach. The Freedom and People's Rights Movement demanded the immediate establishment of an elected national assembly, and the promulgation of a constitution.

The constitution recognized the need for change and modernization after the removal of the shogunate:

We, the Successor to the prosperous Throne of Our Predecessors, do humbly and solemnly swear to the Imperial Founder of Our House and to Our other Imperial Ancestors that, in pursuance of a great policy co-extensive with the Heavens and with the Earth, We shall maintain and secure from decline the ancient form of government. ... In consideration of the progressive tendency of the course of human affairs and in parallel with the advance of civilization, We deem it expedient, in order to give clearness and distinctness to the instructions bequeathed by the Imperial Founder of Our House and by Our other Imperial Ancestors, to establish fundamental laws. ...

Imperial Japan was founded, de jure, after the 1889 signing of Constitution of the Empire of Japan. The constitution formalized much of the Empire's political structure and gave many responsibilities and powers to the Emperor.

- Article 1. The Empire of Japan shall be reigned over and governed by a line of Emperors unbroken for ages eternal.

- Article 2. The Imperial Throne shall be succeeded to by Imperial male descendants, according to the provisions of the Imperial House Law.

- Article 3. The Emperor is sacred and inviolable.

- Article 4. The Emperor is the head of the Empire, combining in Himself the rights of sovereignty, and exercises them, according to the provisions of the present Constitution.

- Article 5. The Emperor exercises the legislative power with the consent of the Imperial Diet.

- Article 6. The Emperor gives sanction to laws, and orders them to be promulgated and executed.

- Article 7. The Emperor convokes the Imperial Diet, opens, closes and prorogues it, and dissolves the House of Representatives.

- Article 11. The Emperor has the supreme command of the Army and Navy.[47]

- Article 13. The Emperor declares war, makes peace, and concludes treaties.

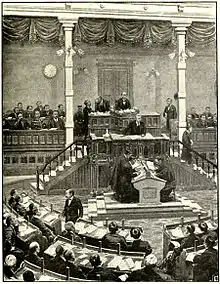

In 1890, the Imperial Diet was established in response to the Meiji Constitution. The Diet consisted of the House of Representatives of Japan and the House of Peers. Both houses opened seats for colonial people as well as Japanese. The Imperial Diet continued until 1947.[8]

Economic development

The process of modernization was closely monitored and heavily subsidized by the Meiji government in close connection with a powerful clique of companies known as zaibatsu (e.g.: Mitsui and Mitsubishi). Borrowing and adapting technology from the West, Japan gradually took control of much of Asia's market for manufactured goods, beginning with textiles. The economic structure became very mercantilistic, importing raw materials and exporting finished products — a reflection of Japan's relative scarcity of raw materials.

Economic reforms included a unified modern currency based on the yen, banking, commercial and tax laws, stock exchanges, and a communications network. The government was initially involved in economic modernization, providing a number of "model factories" to facilitate the transition to the modern period. The transition took time. By the 1890s, however, the Meiji had successfully established a modern institutional framework that would transform Japan into an advanced capitalist economy. By this time, the government had largely relinquished direct control of the modernization process, primarily for budgetary reasons. Many of the former daimyōs, whose pensions had been paid in a lump sum, benefited greatly through investments they made in emerging industries.

Japan emerged from the Tokugawa-Meiji transition as an industrialized nation. From the onset, the Meiji rulers embraced the concept of a market economy and adopted British and North American forms of free enterprise capitalism. Rapid growth and structural change characterized Japan's two periods of economic development after 1868. Initially, the economy grew only moderately and relied heavily on traditional Japanese agriculture to finance modern industrial infrastructure. By the time the Russo-Japanese War began in 1904, 65% of employment and 38% of the gross domestic product (GDP) were still based on agriculture, but modern industry had begun to expand substantially. By the late 1920s, manufacturing and mining amounted to 34% of GDP, compared with 20% for all of agriculture.[48] Transportation and communications developed to sustain heavy industrial development.

From 1894, Japan built an extensive empire that included Taiwan, Korea, Manchuria, and parts of northern China. The Japanese regarded this sphere of influence as a political and economic necessity, which prevented foreign states from strangling Japan by blocking its access to raw materials and crucial sea-lanes. Japan's large military force was regarded as essential to the empire's defense and prosperity by obtaining natural resources that the Japanese islands lacked.

First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War, fought in 1894 and 1895, revolved around the issue of control and influence over Korea under the rule of the Joseon Dynasty. Korea had traditionally been a tributary state of China's Qing Empire, which exerted large influence over the conservative Korean officials who gathered around the royal family of the Joseon kingdom. On February 27, 1876, after several confrontations between Korean isolationists and the Japanese, Japan imposed the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1876, forcing Korea open to Japanese trade. The act blocks any other power from dominating Korea, resolving to end the centuries-old Chinese suzerainty.

On June 4, 1894, Korea requested aid from the Qing Empire in suppressing the Donghak Rebellion. The Qing government sent 2,800 troops to Korea. The Japanese countered by sending an 8,000-troop expeditionary force (the Oshima Composite Brigade) to Korea. The first 400 troops arrived on June 9 en route to Seoul, and 3,000 landed at Incheon on June 12.[49] The Qing government turned down Japan's suggestion for Japan and China to cooperate to reform the Korean government. When Korea demanded that Japan withdraw its troops from Korea, the Japanese refused. In early June 1894, the 8,000 Japanese troops captured the Korean king Gojong, occupied the Royal Palace in Seoul and, by June 25, installed a puppet government in Seoul. The new pro-Japanese Korean government granted Japan the right to expel Qing forces while Japan dispatched more troops to Korea.

China objected and war ensued. Japanese ground troops routed the Chinese forces on the Liaodong Peninsula, and nearly destroyed the Chinese navy in the Battle of the Yalu River. The Treaty of Shimonoseki was signed between Japan and China, which ceded the Liaodong Peninsula and the island of Taiwan to Japan. After the peace treaty, Russia, Germany, and France forced Japan to withdraw from Liaodong Peninsula. Soon afterward, Russia occupied the Liaodong Peninsula, built the Port Arthur fortress, and based the Russian Pacific Fleet in the port. Germany occupied Jiaozhou Bay, built Tsingtao fortress and based the German East Asia Squadron in this port.

Boxer Rebellion

In 1900, Japan joined an international military coalition set up in response to the Boxer Rebellion in the Qing Empire of China. Japan provided the largest contingent of troops: 20,840, as well as 18 warships. Of the total, 20,300 were Imperial Japanese Army troops of the 5th Infantry Division under Lt. General Yamaguchi Motoomi; the remainder were 540 naval rikusentai (marines) from the Imperial Japanese Navy.

At the beginning of the Boxer Rebellion the Japanese only had 215 troops in northern China stationed at Tientsin; nearly all of them were naval rikusentai from the Kasagi and the Atago, under the command of Captain Shimamura Hayao.[50] The Japanese were able to contribute 52 men to the Seymour Expedition.[50] On June 12, 1900, the advance of the Seymour Expedition was halted some 50 kilometres (30 mi) from the capital, by mixed Boxer and Chinese regular army forces. The vastly outnumbered allies withdrew to the vicinity of Tianjin, having suffered more than 300 casualties.[51] The army general staff in Tokyo had become aware of the worsening conditions in China and had drafted ambitious contingency plans,[52] but in the wake of the Triple Intervention five years before, the government refused to deploy large numbers of troops unless requested by the western powers.[52] However three days later, a provisional force of 1,300 troops commanded by Major General Fukushima Yasumasa was to be deployed to northern China. Fukushima was chosen because he spoke fluent English which enabled him to communicate with the British commander. The force landed near Tianjin on July 5.[52]

On June 17, 1900, naval Rikusentai from the Kasagi and Atago had joined British, Russian, and German sailors to seize the Dagu forts near Tianjin.[52] In light of the precarious situation, the British were compelled to ask Japan for additional reinforcements, as the Japanese had the only readily available forces in the region.[52] Britain at the time was heavily engaged in the Boer War, so a large part of the British army was tied down in South Africa. Further, deploying large numbers of troops from its garrisons in India would take too much time and weaken internal security there.[52] Overriding personal doubts, Foreign Minister Aoki Shūzō calculated that the advantages of participating in an allied coalition were too attractive to ignore. Prime Minister Yamagata agreed, but others in the cabinet demanded that there be guarantees from the British in return for the risks and costs of the major deployment of Japanese troops.[52] On July 6, 1900, the 5th Infantry Division was alerted for possible deployment to China, but no timetable was set for this. Two days later, with more ground troops urgently needed to lift the siege of the foreign legations at Peking, the British ambassador offered the Japanese government one million British pounds in exchange for Japanese participation.[52]

Shortly afterward, advance units of the 5th Division departed for China, bringing Japanese strength to 3,800 personnel out of the 17,000 of allied forces.[52] The commander of the 5th Division, Lt. General Yamaguchi Motoomi, had taken operational control from Fukushima. Japanese troops were involved in the storming of Tianjin on July 14,[52] after which the allies consolidated and awaited the remainder of the 5th Division and other coalition reinforcements. By the time the siege of legations was lifted on August 14, 1900, the Japanese force of 13,000 was the largest single contingent and made up about 40% of the approximately 33,000 strong allied expeditionary force.[52] Japanese troops involved in the fighting had acquitted themselves well, although a British military observer felt their aggressiveness, densely-packed formations, and over-willingness to attack cost them excessive and disproportionate casualties.[53] For example, during the Tianjin fighting, the Japanese suffered more than half of the allied casualties (400 out of 730) but comprised less than one quarter (3,800) of the force of 17,000.[53] Similarly at Beijing, the Japanese accounted for almost two-thirds of the losses (280 of 453) even though they constituted slightly less than half of the assault force.[53]

After the uprising, Japan and the Western countries signed the Boxer Protocol with China, which permitted them to station troops on Chinese soil to protect their citizens. After the treaty, Russia continued to occupy all of Manchuria.

Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War was a conflict for control of Korea and parts of Manchuria between the Russian Empire and Empire of Japan that took place from 1904 to 1905. The victory greatly raised Japan's stature in the world of global politics.[54] The war is marked by the Japanese opposition of Russian interests in Korea, Manchuria, and China, notably, the Liaodong Peninsula, controlled by the city of Ryojun.

Originally, in the Treaty of Shimonoseki, Ryojun had been given to Japan. This part of the treaty was overruled by Western powers, which gave the port to the Russian Empire, furthering Russian interests in the region. These interests came into conflict with Japanese interests. The war began with a surprise attack on the Russian Eastern fleet stationed at Port Arthur, which was followed by the Battle of Port Arthur. Those elements that attempted escape were defeated by the Japanese navy under Admiral Togo Heihachiro at the Battle of the Yellow Sea. Following a late start, the Russian Baltic fleet was denied passage through the British-controlled Suez Canal. The fleet arrived on the scene a year later, only to be annihilated in the Battle of Tsushima. While the ground war did not fare as poorly for the Russians, the Japanese forces were significantly more aggressive than their Russian counterparts and gained a political advantage that culminated with the Treaty of Portsmouth, negotiated in the United States by the American president Theodore Roosevelt. As a result, Russia lost the part of Sakhalin Island south of 50 degrees North latitude (which became Karafuto Prefecture), as well as many mineral rights in Manchuria. In addition, Russia's defeat cleared the way for Japan to annex Korea outright in 1910.

Annexation of Korea

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, various Western countries actively competed for influence, trade, and territory in East Asia, and Japan sought to join these modern colonial powers. The newly modernised Meiji government of Japan turned to Korea, then in the sphere of influence of China's Qing dynasty. The Japanese government initially sought to separate Korea from Qing and make Korea a Japanese satellite in order to further their security and national interests.[55]

In January 1876, following the Meiji Restoration, Japan employed gunboat diplomacy to pressure the Joseon Dynasty into signing the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1876, which granted extraterritorial rights to Japanese citizens and opened three Korean ports to Japanese trade. The rights granted to Japan under this unequal treaty,[56] were similar to those granted western powers in Japan following the visit of Commodore Perry.[56] Japanese involvement in Korea increased during the 1890s, a period of political upheaval.

Korea was occupied and declared a Japanese protectorate following the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1905. After proclaimed the founding of the Korean Empire, Korea was officially annexed in Japan through the annexation treaty in 1910.

In Korea, the period is usually described as the "Time of Japanese Forced Occupation" (Hangul: 일제 강점기; Ilje gangjeomgi, Hanja: 日帝强占期). Other terms include "Japanese Imperial Period" (Hangul: 일제시대, Ilje sidae, Hanja: 日帝時代) or "Japanese administration" (Hangul: 왜정, Wae jeong, Hanja: 倭政). In Japan, a more common description is "The Korea of Japanese rule" (日本統治時代の朝鮮, Nippon Tōchi-jidai no Chōsen). The Korean Peninsula was officially part of the Empire of Japan for 35 years, from August 29, 1910, until the formal Japanese rule ended, de jure, on September 2, 1945, upon the surrender of Japan in World War II. The 1905 and 1910 treaties were eventually declared "null and void" by both Japan and South Korea in 1965.

Taishō era (1912–1926)

World War I

Japan entered World War I on the side of the Allies in 1914, seizing the opportunity of Germany's distraction with the European War to expand its sphere of influence in China and the Pacific. Japan declared war on Germany on August 23, 1914. Japanese and allied British Empire forces soon moved to occupy Tsingtao fortress, the German East Asia Squadron base, German-leased territories in China's Shandong Province as well as the Marianas, Caroline, and Marshall Islands in the Pacific, which were part of German New Guinea. The swift invasion in the German territory of the Kiautschou Bay concession and the Siege of Tsingtao proved successful. The German colonial troops surrendered on November 7, 1914, and Japan gained the German holdings.

With its Western allies, notably the United Kingdom, heavily involved in the war in Europe, Japan dispatched a Naval fleet to the Mediterranean Sea to aid Allied shipping. Japan sought further to consolidate its position in China by presenting the Twenty-One Demands to China in January 1915. In the face of slow negotiations with the Chinese government, widespread anti-Japanese sentiment in China, and international condemnation, Japan withdrew the final group of demands, and treaties were signed in May 1915. The Anglo-Japanese Alliance was renewed and expanded in scope twice, in 1905 and 1911, before its demise in 1921. It was officially terminated in 1923.

Siberian Intervention

After the fall of the Tsarist regime and the later provisional regime in 1917, the new Bolshevik government signed a separate peace treaty with Germany. After this, various factions that succeeded the Russian Empire fought amongst themselves in a multi-sided civil war.

In July 1918, President Wilson asked the Japanese government to supply 7,000 troops as part of an international coalition of 25,000 troops planned to support the American Expeditionary Force Siberia. Prime Minister Terauchi Masatake agreed to send 12,000 troops but under the Japanese command rather than as part of an international coalition. The Japanese had several hidden motives for the venture, which included an intense hostility and fear of communism; a determination to recoup historical losses to Russia; and the desire to settle the "northern problem" in Japan's security, either through the creation of a buffer state or through outright territorial acquisition.

By November 1918, more than 70,000 Japanese troops under Chief of Staff Yui Mitsue had occupied all ports and major towns in the Russian Maritime Provinces and eastern Siberia. Japan received 765 Polish orphans from Siberia.[57][58]

In June 1920, around 450 Japanese civilians and 350 Japanese soldiers, along with Russian White Army supporters, were massacred by partisan forces associated with the Red Army at Nikolayevsk on the Amur River; the United States and its allied coalition partners consequently withdrew from Vladivostok after the capture and execution of White Army leader Admiral Aleksandr Kolchak by the Red Army. However, the Japanese decided to stay, primarily due to fears of the spread of Communism so close to Japan and Japanese-controlled Korea and Manchuria. The Japanese army provided military support to the Japanese-backed Provisional Priamurye Government based in Vladivostok against the Moscow-backed Far Eastern Republic.

The continued Japanese presence concerned the United States, which suspected that Japan had territorial designs on Siberia and the Russian Far East. Subjected to intense diplomatic pressure by the United States and United Kingdom, and facing increasing domestic opposition due to the economic and human cost, the administration of Prime Minister Katō Tomosaburō withdrew the Japanese forces in October 1922. Japanese casualties from the expedition were 5,000 dead from combat or illness, with the expedition costing over 900 million yen.

"Taishō Democracy"

The two-party political system that had been developing in Japan since the turn of the century came of age after World War I, giving rise to the nickname for the period, "Taishō Democracy". The public grew disillusioned with the growing national debt and the new election laws, which retained the old minimum tax qualifications for voters. Calls were raised for universal suffrage and the dismantling of the old political party network. Students, university professors, and journalists, bolstered by labor unions and inspired by a variety of democratic, socialist, communist, anarchist, and other thoughts, mounted large but orderly public demonstrations in favor of universal male suffrage in 1919 and 1920.

The election of Katō Komei as Prime Minister of Japan continued democratic reforms that had been advocated by influential individuals on the left. This culminated in the passage of universal male suffrage in March 1925. This bill gave all male subjects over the age of 25 the right to vote, provided they had lived in their electoral districts for at least one year and were not homeless. The electorate thereby increased from 3.3 million to 12.5 million.[59]

In the political milieu of the day, there was a proliferation of new parties, including socialist and communist parties. Fear of a broader electorate, left-wing power, and the growing social change led to the passage of the Peace Preservation Law in 1925, which forbade any change in the political structure or the abolition of private property.

In 1932, Park Chun-kum was elected to the House of Representatives in the Japanese general election as the first person elected from a colonial background.[60] In 1935, democracy was introduced in Taiwan and in response to Taiwanese public opinion, local assemblies were established.[61] In 1942, 38 colonial people were elected to local assemblies of the Japanese homeland.[60]

Unstable coalitions and divisiveness in the Diet led the Kenseikai (憲政会 Constitutional Government Association) and the Seiyū Hontō (政友本党 True Seiyūkai) to merge as the Rikken Minseitō (立憲民政党 Constitutional Democratic Party) in 1927. The Rikken Minseitō platform was committed to the parliamentary system, democratic politics, and world peace. Thereafter, until 1932, the Seiyūkai and the Rikken Minseitō alternated in power.

Despite the political realignments and hope for more orderly government, domestic economic crises plagued whichever party held power. Fiscal austerity programs and appeals for public support of such conservative government policies as the Peace Preservation Law—including reminders of the moral obligation to make sacrifices for the emperor and the state—were attempted as solutions.

Early Shōwa (1926–1930)

Rise of militarism and its social organisations

Important institutional links existed between the party in government (Kōdōha) and military and political organizations, such as the Imperial Young Federation and the "Political Department" of the Kempeitai. Amongst the himitsu kessha (secret societies), the Kokuryu-kai and Kokka Shakai Shugi Gakumei (National Socialist League) also had close ties to the government. The Tonarigumi (residents committee) groups, the Nation Service Society (national government trade union), and Imperial Farmers Association were all allied as well. Other organizations and groups related with the government in wartime were the Double Leaf Society, Kokuhonsha, Taisei Yokusankai, Imperial Youth Corps, Keishichō (to 1945), Shintoist Rites Research Council, Treaty Faction, Fleet Faction, and Volunteer Fighting Corps.

Nationalism and decline of democracy

Sadao Araki was an important figurehead and founder of the Army party and the most important militarist thinker in his time. His first ideological works date from his leadership of the Kōdōha (Imperial Benevolent Rule or Action Group), opposed by the Tōseiha (Control Group) led by General Kazushige Ugaki. He linked the ancient (bushido code) and contemporary local and European fascist ideals (see Statism in Shōwa Japan), to form the ideological basis of the movement (Shōwa nationalism).

From September 1931, the Japanese were becoming more locked into the course that would lead them into the Second World War, with Araki leading the way. Totalitarianism, militarism, and expansionism were to become the rule, with fewer voices able to speak against it. In a September 23 news conference, Araki first mentioned the philosophy of "Kōdōha" (The Imperial Way Faction). The concept of Kodo linked the Emperor, the people, land, and morality as indivisible. This led to the creation of a "new" Shinto and increased Emperor worship.

On February 26, 1936, a coup d'état was attempted (the February 26 Incident). Launched by the ultranationalist Kōdōha faction with the military, it ultimately failed due to the intervention of the Emperor. Kōdōha members were purged from the top military positions and the Tōseiha faction gained dominance. However, both factions believed in expansionism, a strong military, and a coming war. Furthermore, Kōdōha members, while removed from the military, still had political influence within the government.

The state was being transformed to serve the Army and the Emperor. Symbolic katana swords came back into fashion as the martial embodiment of these beliefs, and the Nambu pistol became its contemporary equivalent, with the implicit message that the Army doctrine of close combat would prevail. The final objective, as envisioned by Army thinkers such as Sadao Araki and right-wing line followers, was a return to the old Shogunate system, but in the form of a contemporary Military Shogunate. In such a government the Emperor would once more be a figurehead (as in the Edo period). Real power would fall to a leader very similar to a führer or duce, though with the power less nakedly held. On the other hand, the traditionalist Navy militarists defended the Emperor and a constitutional monarchy with a significant religious aspect.

A third point of view was supported by Prince Chichibu, a brother of Emperor Shōwa, who repeatedly counseled him to implement a direct imperial rule, even if that meant suspending the constitution.[62]

With the launching of the Imperial Rule Assistance Association in 1940 by Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe, Japan would turn to a form of government that resembled totalitarianism. This unique style of government, very similar to fascism, was known as Shōwa Statism.

In the early twentieth century, a distinctive style of architecture was developed for the empire. Now referred to as Imperial Crown Style (帝冠様式, teikan yōshiki), before the end of World War II, it was originally referred to as Emperor's Crown Amalgamate Style, and sometimes Emperor's Crown Style (帝冠式, Teikanshiki). The style is identified by Japanese-style roofing on top of Neoclassical styled buildings; and can have a centrally elevated structure with a pyramidal dome. The prototype for this style was developed by architect Shimoda Kikutaro in his proposal for the Imperial Diet Building (present National Diet Building) in 1920 – although his proposal was ultimately rejected. Outside of the Japanese mainland, in places like Taiwan and Korea, Imperial Crown Style architecture often included regional architectural elements.[63]

Overall, during the 1920s, Japan changed its direction toward a democratic system of government. However, parliamentary government was not rooted deeply enough to withstand the economic and political pressures of the 1930s, during which military leaders became increasingly influential. These shifts in power were made possible by the ambiguity and imprecision of the Meiji Constitution, particularly as regarded the position of the Emperor in relation to the constitution.

Economic factors

During the 1920s, the whole global economy was dubbed as "a decade of global uncertainty". At the same time, the zaibatsu trading groups (principally Mitsubishi, Mitsui, Sumitomo, and Yasuda) looked towards great future expansion. Their main concern was a shortage of raw materials. Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe combined social concerns with the needs of capital, and planned for expansion. Their economic growth was stimulated by certain domestic policies and it can be seen in the steady and progressive increase of materials such as in the iron, steel and chemical industry.[64]

The main goals of Japan's expansionism were acquisition and protection of spheres of influence, maintenance of territorial integrity, acquisition of raw materials, and access to Asian markets. Western nations, notably the United Kingdom, France, and the United States, had for long exhibited great interest in the commercial opportunities in China and other parts of Asia. These opportunities had attracted Western investment because of the availability of raw materials for both domestic production and re-export to Asia. Japan desired these opportunities in planning the development of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

The Great Depression, just as in many other countries, hindered Japan's economic growth. The Japanese Empire's main problem lay in that rapid industrial expansion had turned the country into a major manufacturing and industrial power that required raw materials; however, these had to be obtained from overseas, as there was a critical lack of natural resources on the home islands.

.jpg.webp)

In the 1920s and 1930s, Japan needed to import raw materials such as iron, rubber, and oil to maintain strong economic growth. Most of these resources came from the United States. The Japanese felt that acquiring resource-rich territories would establish economic self-sufficiency and independence, and they also hoped to jump-start the nation's economy in the midst of the depression. As a result, Japan set its sights on East Asia, specifically Manchuria with its many resources; Japan needed these resources to continue its economic development and maintain national integrity.

Later Shōwa (1931–1941)

Prewar expansionism

Manchuria

In 1931, Japan invaded and conquered Northeast China (Manchuria) with little resistance. Japan claimed that this invasion was a liberation of the local Manchus from the Chinese, although the majority of the population were Han Chinese as a result of the large scale settlement of Chinese in Manchuria in the 19th century. Japan then established a puppet regime called Manchukuo (Chinese: 滿洲國), and installed the last Manchu Emperor of China, Puyi, as the official head of state. Jehol, a Chinese territory bordering Manchukuo, was later also taken in 1933. This puppet regime had to carry on a protracted pacification campaign against the Anti-Japanese Volunteer Armies in Manchuria. In 1936, Japan created a similar Mongolian puppet state in Inner Mongolia named Mengjiang (Chinese: 蒙疆), which was also predominantly Chinese as a result of recent Han immigration to the area. At that time, East Asians were banned from immigration to North America and Australia, but the newly established Manchukuo was open to immigration of Asians. Japan had an emigration plan to encourage colonization; the Japanese population in Manchuria subsequently grew to 850,000.[65] With rich natural resources and labor force in Manchuria, army-owned corporations turned Manchuria into a solid material support machine of the Japanese Army.[66]

Second Sino-Japanese War

Japan invaded China proper in 1937, beginning a war against a united front of Mao Zedong's communists and Chiang Kai-shek's nationalists. On December 13 of that same year, the Nationalist capital of Nanjing surrendered to Japanese troops. In the event known as the "Nanjing Massacre", Japanese troops massacred a large number of the defending garrison. It is estimated that as many as 200,000 to 300,000 including civilians, may have been killed, although the actual numbers are uncertain and possibly inflated coupled with the fact that the government of the People's Republic of China has never undertaken a full accounting of the massacre. In total, an estimated 20 million Chinese, mostly civilians, were killed during World War II. A puppet state was also set up in China quickly afterwards, headed by Wang Jingwei. The Second Sino-Japanese War continued into World War II with the Communists and Nationalists in a temporary and uneasy nominal alliance against the Japanese.

Clashes with the Soviet Union

In 1938, the Japanese 19th Division entered territory claimed by the Soviet Union, leading to the Battle of Lake Khasan. This incursion was founded in the Japanese belief that the Soviet Union misinterpreted the demarcation of the boundary, as stipulated in the Treaty of Peking, between Imperial Russia and Manchu China (and subsequent supplementary agreements on demarcation), and furthermore, that the demarcation markers were tampered with.

On May 11, 1939, in the Nomonhan Incident (Battle of Khalkhin Gol), a Mongolian cavalry unit of some 70 to 90 men entered the disputed area in search of grazing for their horses, and encountered Manchukuoan cavalry, who drove them out. Two days later the Mongolian force returned and the Manchukoans were unable to evict them.

The IJA 23rd Division and other units of the Kwantung Army then became involved. Joseph Stalin ordered Stavka, the Red Army's high command, to develop a plan for a counterstrike against the Japanese. In late August, Georgy Zhukov employed encircling tactics that made skillful use of superior artillery, armor, and air forces; this offensive nearly annihilated the 23rd Division and decimated the IJA 7th Division. On September 15 an armistice was arranged. Nearly two years later, on April 13, 1941, the parties signed a Neutrality Pact, in which the Soviet Union pledged to respect the territorial integrity and inviolability of Manchukuo, while Japan agreed similarly for the Mongolian People's Republic.

Tripartite Pact

In 1938, Japan prohibited the expulsion of the Jews in Japan, Manchuria, and China in accordance with the spirit of racial equality on which Japan had insisted for many years.[67][68]

The Second Sino-Japanese War had seen tensions rise between Imperial Japan and the United States; events such as the Panay incident and the Nanjing Massacre turned American public opinion against Japan. With the occupation of French Indochina in the years of 1940–41, and with the continuing war in China, the United States and its allies placed embargoes on Japan of strategic materials such as scrap metal and oil, which were vitally needed for the war effort. The Japanese were faced with the option of either withdrawing from China and losing face or seizing and securing new sources of raw materials in the resource-rich, European-controlled colonies of Southeast Asia—specifically British Malaya and the Dutch East Indies (modern-day Indonesia).

On September 27, 1940, Japan signed the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy. Their objectives were to "establish and maintain a new order of things" in their respective world regions and spheres of influence, with Germany and Italy in Europe, and Japan in Asia. The signatories of this alliance became known as the Axis Powers. The pact also called for mutual protection—if any one of the member powers was attacked by a country not already at war, excluding the Soviet Union and for technological and economic cooperation between the signatories.

For the sake of their own people and nation, Prime Minister Konoe formed the Taisei Yokusankai (Imperial Rule Assistance Association) on October 12, 1940, as a ruling party in Japan.

In 1940 Japan celebrated the 2600th anniversary of Jimmu's ascension and built a monument to Hakkō ichiu despite the fact that all historians knew Jimmu was a made up figure. In 1941 the Japanese government charged the one historian who dared to challenge Jimmu's existence publicly, Tsuda Sokichi.[70] During the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Second World War, the firm Iwanami Shoten was repeatedly censored because of its positions against the war and the Emperor. Shigeo Iwanami was even sentenced to two months in prison for the publication of the banned works of Tsuda Sōkichi (a sentence which he did not serve, however). Shortly before his death in 1946, he founded the newspaper Sekai, which had a great influence in post-war Japanese intellectual circles.[71] The early 20th century historian Tsuda Sōkichi, who put forward the then-controversial theory that the Kojiki's accounts were not based on history (as Edo period kokugaku and State Shinto ideology believed them to be) but rather propagandistic myths concocted to explain and legitimize the rule of the imperial (Yamato) dynasty, also saw Susanoo as a negative figure, arguing that he was created to serve as the rebellious opposite of the imperial ancestress Amaterasu.[72] A historian in 20th century, Sokichi Tsuda’s view of history, which has become mainstream after the World War II, is based on his idea. Many scholars today also believe that the mythology of Takamagahara in Kojiki was created by the ruling class to make people believe that the class was precious because they originated in the heavenly realm.[73][74]

World War II (1941–1945)

Facing an oil embargo by the United States as well as dwindling domestic reserves, the Japanese government decided to execute a plan developed by Isoroku Yamamoto to attack the United States Pacific Fleet in Hawaii. While the United States was neutral and continued negotiating with Japan for possible peace in Asia, the Imperial Japanese Navy at the same time made its surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in Honolulu on December 7, 1941. As a result, the U.S. battleship fleet was decimated and almost 2,500 people died in the attack that day. The primary objective of the attack was to incapacitate the United States long enough for Japan to establish its long-planned South East Asian empire and defensible buffer zones. The American public saw the attack as barbaric and treacherous and rallied against the Japanese. Four days later, Adolf Hitler of Germany, and Benito Mussolini of Italy declared war on the United States, merging the separate conflicts. The United States entered the European Theatre and Pacific Theater in full force, thereby bringing the United States to World War II on the side of the Allies.

Japanese conquests

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese launched offensives against Allied forces in East and Southeast Asia, with simultaneous attacks in British Hong Kong, British Malaya and the Philippines. Hong Kong surrendered to the Japanese on December 25. In Malaya the Japanese overwhelmed an Allied army composed of British, Indian, Australian and Malay forces. The Japanese were quickly able to advance down the Malayan Peninsula, forcing the Allied forces to retreat towards Singapore. The Allies lacked aircover and tanks; the Japanese had complete air superiority. The sinking of HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse on December 10, 1941, led to the east coast of Malaya being exposed to Japanese landings and the elimination of British naval power in the area. By the end of January 1942, the last Allied forces crossed the strait of Johore and into Singapore.

In the Philippines, the Japanese pushed the combined American-Filipino force towards the Bataan Peninsula and later the island of Corregidor. By January 1942, General Douglas MacArthur and President Manuel L. Quezon were forced to flee in the face of Japanese advance. This marked one of the worst defeats suffered by the Americans, leaving over 70,000 American and Filipino prisoners of war in the custody of the Japanese. On February 15, 1942, Singapore, due to the overwhelming superiority of Japanese forces and encirclement tactics, fell to the Japanese, causing the largest surrender of British-led military personnel in history. An estimated 80,000 Australian, British and Indian troops were taken as prisoners of war, joining 50,000 taken in the Japanese invasion of Malaya (modern day Malaysia). The Japanese then seized the key oil production zones of Borneo, Central Java, Malang, Cebu, Sumatra, and Dutch New Guinea of the late Dutch East Indies, defeating the Dutch forces.[75] However, Allied sabotage had made it difficult for the Japanese to restore oil production to its pre-war peak.[76] The Japanese then consolidated their lines of supply through capturing key islands of the Pacific, including Guadalcanal.

Tide turns

Japanese military strategists were keenly aware of the unfavorable discrepancy between the industrial potential of Japan and the United States. Because of this they reasoned that Japanese success hinged on their ability to extend the strategic advantage gained at Pearl Harbor with additional rapid strategic victories. The Japanese Command reasoned that only decisive destruction of the United States' Pacific Fleet and conquest of its remote outposts would ensure that the Japanese Empire would not be overwhelmed by America's industrial might.

In April 1942, Japan was bombed for the first time in the Doolittle Raid. During the same month, after the Japanese victory in the Battle of Bataan, the Bataan Death March was conducted, where 5,650 to 18,000 Filipinos died under the rule of the imperial army.[77] In May 1942, failure to decisively defeat the Allies at the Battle of the Coral Sea, in spite of Japanese numerical superiority, equated to a strategic defeat for the Japanese. This setback was followed in June 1942 by the catastrophic loss of four fleet carriers at the Battle of Midway, the first decisive defeat for the Imperial Japanese Navy. It proved to be the turning point of the war as the Navy lost its offensive strategic capability and never managed to reconstruct the "'critical mass' of both large numbers of carriers and well-trained air groups".[78] Australian land forces defeated Japanese Marines in New Guinea at the Battle of Milne Bay in September 1942, which was the first land defeat suffered by the Japanese in the Pacific. Further victories by the Allies at Guadalcanal in September 1942 and New Guinea in 1943 put the Empire of Japan on the defensive for the remainder of the war, with Guadalcanal in particular sapping their already-limited oil supplies.[76] During 1943 and 1944, Allied forces, backed by the industrial might and vast raw material resources of the United States, advanced steadily towards Japan. The Sixth United States Army, led by General MacArthur, landed on Leyte on October 20, 1944. The Palawan massacre was committed by the imperial army against Filipinos in December 1944.[79] In the subsequent months, during the Philippines campaign (1944–45), the Allies, including the combined United States forces together with the native guerrilla units, recaptured the Philippines.

Surrender

%252C_on_8_October_1945_(80-G-351726).jpg.webp)

By 1944, the Allies had seized or bypassed and neutralized many of Japan's strategic bases through amphibious landings and bombardment. This, coupled with the losses inflicted by Allied submarines on Japanese shipping routes, began to strangle Japan's economy and undermine its ability to supply its army. By early 1945, the US Marines had wrested control of the Ogasawara Islands in several hard-fought battles such as the Battle of Iwo Jima, marking the beginning of the fall of the islands of Japan. After securing airfields in Saipan and Guam in the summer of 1944, the United States Army Air Forces conducted an intense strategic bombing campaign by having B-29 Superfortress bombers in nighttime low altitude incendiary raids, burning Japanese cities in an effort to pulverize Japan's war industry and shatter its morale. The Operation Meetinghouse raid on Tokyo on the night of March 9–10, 1945, led to the deaths of approximately 120,000 civilians. Approximately 350,000–500,000 civilians died in 67 Japanese cities as a result of the incendiary bombing campaign on Japan. Concurrent with these attacks, Japan's vital coastal shipping operations were severely hampered with extensive aerial mining by the US's Operation Starvation. Regardless, these efforts did not succeed in persuading the Japanese military to surrender. In mid-August 1945, the United States dropped nuclear weapons on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. These bombings were the first and only combat use of nuclear weaponry. These two bombs killed approximately 120,000 people in a matter of seconds, and as many as a result of nuclear radiation in the following weeks, months and years. The bombs killed as many as 140,000 people in Hiroshima and 80,000 in Nagasaki by the end of 1945.

At the Yalta agreement, the US, the UK, and the USSR had agreed that the USSR would enter the war on Japan within three months of the defeat of Germany in Europe. This Soviet–Japanese War led to the fall of Japan's Manchurian occupation, Soviet occupation of South Sakhalin island, and a real, imminent threat of Soviet invasion of the home islands of Japan. This was a significant factor for some internal parties in the Japanese decision to surrender to the US[80] and gain some protection, rather than face simultaneous Soviet invasion as well as defeat by the US and its allies. Likewise, the superior numbers of the armies of the Soviet Union in Europe was a factor in the US decision to demonstrate the use of atomic weapons to the USSR, just as the Allied victory in Europe was evolving into the division of Germany and Berlin, the division of Europe with the Iron Curtain and the subsequent Cold War.

Having ignored (mokusatsu) the Potsdam Declaration, the Empire of Japan surrendered and ended World War II after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the declaration of war by the Soviet Union and subsequent invasion of Manchuria and other territories. In a national radio address on August 15, Emperor Hirohito announced the surrender to the Japanese people by Gyokuon-hōsō.

Occupation of Japan

A period known as occupied Japan followed after the war, largely spearheaded by US Army General Douglas MacArthur to revise the Japanese constitution and de-militarize the nation. The Allied occupation, including concurrent economic and political assistance, continued until 1952. Allied forces ordered Japan to abolish the Meiji Constitution and enforce the 1947 Constitution of Japan. This new constitution was imposed by the United States under the supervision of MacArthur. MacArthur included Article 9 which changed Japan into a pacifist country.[81]

Upon adoption of the 1947 constitution, the Empire of Japan dissolved and became simply the state of Japan, and all overseas territories were lost. Japan was reduced to the territories that were traditionally within the Japanese cultural sphere pre-1895: the four main islands (Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, and Shikoku), the Ryukyu Islands, and the Nanpō Islands. The Kuril Islands also historically belonged to Japan[82] and were first inhabited by the Ainu people before coming under the control of the Matsumae clan during the Edo Period.[83] However, the Kuril Islands were not included due to a dispute with the Soviet Union.[8]

Japan adopted a parliamentary-based political system, and the role of the Emperor became symbolic. The US occupation forces were fully responsible for protecting Japan from external threats. Japan only had a minor police force for domestic security. Japan was under the sole control of the United States. This was the only time in Japanese history that it was occupied by a foreign power.[84]

General MacArthur later commended the new Japanese government that he helped establish and the new Japanese period when he was about to send the American forces to the Korean War:

The Japanese people, since the war, have undergone the greatest reformation recorded in modern history. With a commendable will, eagerness to learn, and marked capacity to understand, they have, from the ashes left in war's wake, erected in Japan an edifice dedicated to the supremacy of individual liberty and personal dignity; and in the ensuing process there has been created a truly representative government committed to the advance of political morality, freedom of economic enterprise, and social justice. Politically, economically, and socially Japan is now abreast of many free nations of the earth and will not again fail the universal trust. ... I sent all four of our occupation divisions to the Korean battlefront without the slightest qualms as to the effect of the resulting power vacuum upon Japan. The results fully justified my faith. I know of no nation more serene, orderly, and industrious, nor in which higher hopes can be entertained for future constructive service in the advance of the human race.

For historian John W. Dower:

In retrospect, apart from the military officer corps, the purge of alleged militarists and ultranationalists that was conducted under the Occupation had relatively small impact on the long-term composition of men of influence in the public and private sectors. The purge initially brought new blood into the political parties, but this was offset by the return of huge numbers of formerly purged conservative politicians to national as well as local politics in the early 1950s. In the bureaucracy, the purge was negligible from the outset. ... In the economic sector, the purge similarly was only mildly disruptive, affecting less than sixteen hundred individuals spread among some four hundred companies. Everywhere one looks, the corridors of power in postwar Japan are crowded with men whose talents had already been recognized during the war years, and who found the same talents highly prized in the 'new' Japan.[85]

Influential personnel

Political

In the administration of Japan dominated by the military political movement during World War II, the civil central government was under the management of military men and their right-wing civilian allies, along with members of the nobility and Imperial Family. The Emperor was in the center of this power structure as supreme Commander-in-Chief of the Imperial Armed Forces and head of state.

Early period:

- HIH Prince Kitashirakawa Yoshihisa

- HIH Prince Kitashirakawa Naruhisa

- HIH Prince Komatsu Akihito

- HIH Marquess Michitsune Koga

- Prince Yamagata Aritomo

- Prince Itō Hirobumi

- Prince Katsura Tarō

World War II:

- Prince Fumimaro Konoe

- Kōki Hirota

- Hideki Tojo

Prince Itō Hirobumi

Prince Itō Hirobumi His Imperial Highness Prince Kitashirakawa Naruhisa, the 3rd head of a collateral branch of the Japanese Imperial Family

His Imperial Highness Prince Kitashirakawa Naruhisa, the 3rd head of a collateral branch of the Japanese Imperial Family His Imperial Highness Marquess Michitsune Koga, a member of the Imperial Family, descending from Emperor Murakami. He is the former Governor of Tokyo Prefecture

His Imperial Highness Marquess Michitsune Koga, a member of the Imperial Family, descending from Emperor Murakami. He is the former Governor of Tokyo Prefecture His Imperial Highness Count Nagayoshi Ogasawara, a member of the Imperial Family

His Imperial Highness Count Nagayoshi Ogasawara, a member of the Imperial Family

Diplomats

Early period

- Marquess Komura Jutarō: Boxer Protocol & the Treaty of Portsmouth

- Count Mutsu Munemitsu: Treaty of Shimonoseki

- Count Hayashi Tadasu: Anglo-Japanese Alliance

- Count Kaneko Kentarō: envoy to the United States

- Viscount Aoki Shūzō: Foreign Minister of Japan, Anglo-Japanese Treaty of Commerce and Navigation

- Viscount Torii Tadafumi: Vice Consul to the Kingdom of Hawaii

- Viscount Ishii Kikujiro: Lansing–Ishii Agreement

World War II

- Baron Hiroshi Ōshima: Japanese ambassador to Nazi Germany

Military

The Empire of Japan's military was divided into two main branches: the Imperial Japanese Army and the Imperial Japanese Navy. To coordinate operations, the Imperial General Headquarters, headed by the Emperor, was established in 1893. Prominent generals and leaders:

Early period

- Field Marshal Prince Yamagata Aritomo: Chief of staff of the Army, Prime Minister of Japan, Founder of the IJA

- Field Marshal Prince Ōyama Iwao: Chief of staff of the Army

- Field Marshal Prince Komatsu Akihito: Chief of staff of the Army

- Field Marshal Marquis Nozu Michitsura:

- General Count Nogi Maresuke: Governor of Taiwan

- General Count Akiyama Yoshifuru: Chief of staff of the Army

- General Count Kuroki Tamemoto

- General Count Nagaoka Gaishi

- Lieutenant General Baron Ōshima Ken'ichi: Chief of staff of the Army, Minister of War during World War I

- General Viscount Kodama Gentarō: Chief of staff of the Army, Governor of Taiwan

World War II

- Field Marshal Prince Kotohito Kan'in: Chief of staff of the Army

- Field Marshal Hajime Sugiyama: Chief of staff of the Army

- General Senjūrō Hayashi: Chief of staff of the Army, Prime Minister of Japan

- General Hideki Tōjō: Prime Minister of Japan

- General Yoshijirō Umezu: Chief of staff of the Army

Early period

- Marshal Admiral Prince Higashifushimi Yorihito (1867–1922)

- Marshal Admiral Marquess Tōgō Heihachirō (1847–1934), Battle of Tsushima

- Marshal Admiral Count Itō Sukeyuki (1843–1914)

- Admiral Count Kawamura Sumiyoshi (1836–1904)

- Marshal Admiral Viscount Inoue Yoshika (1845–1929)

- Marshal Admiral Baron Ijuin Gorō (1852–1921)

- Marshal Admiral Baron Katō Tomosaburō (1861–1923)

- Admiral Baron Akamatsu Noriyoshi (1841–1920)

- Vice Admiral Akiyama Saneyuki (1868–1918), Battle of Tsushima

World War II

- Marshal Admiral Mineichi Koga (1885–1944)

- Marshal Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto (1884–1943), attack on Pearl Harbor, Battle of Midway

- Marshal Admiral Osami Nagano (1880–1947)

- Admiral Chūichi Nagumo (1887–1944), attack on Pearl Harbor, Battle of Midway[86]

- Rear Admiral Viscount Morio Matsudaira (1878–1944)

Demographics

.png.webp)

.png.webp)

Notable scholars/scientists

19th century

Hirase Sakugorō (1856–1925) was a botanist, who won the Imperial Prize in 1912.

Hirase Sakugorō (1856–1925) was a botanist, who won the Imperial Prize in 1912. Ōtsuki Fumihiko (1847–1928), editor of two well-known Japanese-language dictionaries, Genkai (言海, "sea of words", 1891) and its successor Daigenkai (大言海, "great sea of words", 1932–1937)

Ōtsuki Fumihiko (1847–1928), editor of two well-known Japanese-language dictionaries, Genkai (言海, "sea of words", 1891) and its successor Daigenkai (大言海, "great sea of words", 1932–1937) Baron Keisuke Ito (1803–1901) was a biologist and a professor at the Imperial University in Tokyo (University of Tokyo).

Baron Keisuke Ito (1803–1901) was a biologist and a professor at the Imperial University in Tokyo (University of Tokyo). Kiyoo Wadati (1902–1995) was a seismologist, who won the Imperial Prize in 1932.

Kiyoo Wadati (1902–1995) was a seismologist, who won the Imperial Prize in 1932. Teiji Takagi (1875–1960) was a mathematician who made seminal contributions to class field theory, and a member of the selection committee for the first Fields Medal.

Teiji Takagi (1875–1960) was a mathematician who made seminal contributions to class field theory, and a member of the selection committee for the first Fields Medal.

Anthropologists, ethnologists, archaeologists, and historians

- Ōtsuki Fumihiko (1847–1928)

- Yusuke Hashiba (1851–1921)

- Koganei Yoshikiyo (1859–1944)

- Naitō Torajirō (1866–1934)

- Inō Kanori (1867–1925)

- Torii Ryūzō (1870–1953)

- Fujioka Katsuji (1872–1935)

- Masaharu Anesaki (1873–1949)

- Kunio Yanagita (1875–1962)

- Ushinosuke Mori (1877–1926)

- Ryūsaku Tsunoda (1877–1964)

- Kōsaku Hamada (1881–1938)

Kyōsuke Kindaichi (1882–1971)

Kyōsuke Kindaichi (1882–1971)- Tetsuji Morohashi (1883–1982)

- Tsuruko Haraguchi (1886–1915)

- Shinobu Orikuchi (1887–1953)

- Zenchū Nakahara (1890–1964)

Medical scientists, biologists, evolutionary theorists, and geneticists

- Keisuke Ito (1803–1901)

- Kusumoto Ine (1827–1903)

- Nagayo Sensai (1838–1902)

- Tanaka Yoshio (1838–1916)

- Nagai Nagayoshi (1844–1929)

- Miyake Hiizu (1848–1938)

- Takaki Kanehiro (1849–1920)

- Kitasato Shibasaburō (1853–1931)

Hirase Sakugorō (1856–1925)

Hirase Sakugorō (1856–1925)- Jinzō Matsumura (1856–1928)

- Juntaro takahashi (1856–1920)

- Aoyama Tanemichi (1859–1917)

- Yoichirō Hirase (1859–1925)

- Ishikawa Chiyomatsu (1861–1935)

- Tomitaro Makino (1862–1957)

- Yamagiwa Katsusaburō (1863–1930)

Yu Fujikawa (1865–1940)

Yu Fujikawa (1865–1940)- Fujiro Katsurada (1867–1946)

- Kamakichi Kishinouye (1867–1929)

- Yasuyoshi Shirasawa (1868–1947)

- Takuji Iwasaki (1869–1937)

- Kiyoshi Shiga (1871–1957)

- Heijiro Nakayama (1871–1956)

Sunao Tawara (1873–1952)

Sunao Tawara (1873–1952)- Bunzō Hayata (1874–1934)

Ryukichi Inada (1874–1950)

Ryukichi Inada (1874–1950)- Kensuke Mitsuda (1876–1964)

Hideyo Noguchi (1876–1928)

Hideyo Noguchi (1876–1928)- Fukushi Masaichi (1878–1956)

Takaoki Sasaki (1878–1966)

Takaoki Sasaki (1878–1966) Gennosuke Fuse (1880–1946)

Gennosuke Fuse (1880–1946)- Kono Yasui (1880–1971)

- Hakaru Hashimoto (1881–1934)

- Ichiro Miyake (1881–1964)

- Kunihiko Hashida (1882–1945)

- Takenoshin Nakai (1882–1952)

- Kyusaku Ogino (1882–1975)

- Gen-ichi Koidzumi (1883–1953)

- Makoto Nishimura (1883–1956)

- Shintarō Hirase (1884–1939)

- Tamezo Mori (1884–1962)

- Kanesuke Hara (1885–1962)

- Chōzaburō Tanaka (1885–1976)

- Michiyo Tsujimura (1888–1969)

- Yaichirō Okada (1892–1976)

- Ikuro Takahashi (1892–1981)

Hitoshi Kihara (1893–1986)

Hitoshi Kihara (1893–1986)- Satyu Yamaguti (1894–1976)

- Kinichiro Sakaguchi (1897–1994)

- Minoru Shirota (1899–1982)

- Genkei Masamune (1899–1993)