United States Department of Defense

The United States Department of Defense (DoD,[5] USDOD or DOD) is an executive branch department of the federal government charged with coordinating and supervising all agencies and functions of the government directly related to national security and the United States Armed Forces. The DoD is the largest employer in the world,[6] with over 1.4 million active-duty service members (soldiers, marines, sailors, airmen, and guardians) as of 2021.[7] More employees include over 826,000 National Guard and reservists from the armed forces, and over 732,000 civilians[8] bringing the total to over 2.8 million employees.[2] Headquartered at the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia, just outside Washington, D.C., the DoD's stated mission is to provide "the military forces needed to deter war and ensure our nation's security".[9][10]

Seal | |

Logo | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 18 September 1947 (as National Military Establishment) |

| Preceding agencies |

|

| Type | Executive Department |

| Jurisdiction | U.S. Federal Government |

| Headquarters | The Pentagon Arlington County, Virginia, U.S. 38°52′16″N 77°3′21″W |

| Employees | |

| Annual budget | US$721.5 billion (FY2020)[3] |

| Agency executives |

|

| Child agencies |

|

| Website | www |

| United States Armed Forces |

|---|

|

| Executive departments |

| Staff |

| Military departments |

|

| Military service branches |

|

| Command structure |

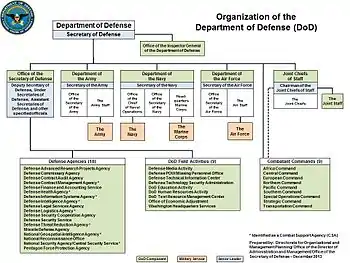

The Department of Defense is headed by the secretary of defense, a cabinet-level head who reports directly to the president of the United States. Beneath the Department of Defense are three subordinate military departments: the Department of the Army, the Department of the Navy, and the Department of the Air Force. In addition, four national intelligence services are subordinate to the Department of Defense: the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), the National Security Agency (NSA), the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), and the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO). Other Defense agencies include the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the Defense Logistics Agency (DLA), the Missile Defense Agency (MDA), the Defense Health Agency (DHA), Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA), the Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency (DCSA), the Space Development Agency (SDA) and the Pentagon Force Protection Agency (PFPA), all of which are subordinate to the secretary of defense. Additionally, the Defense Contract Management Agency (DCMA) is responsible for administering contracts for the DoD. Military operations are managed by eleven regional or functional Unified combatant commands. The Department of Defense also operates several joint services schools, including the Eisenhower School (ES) and the National War College (NWC).

History

Faced with rising tensions between the Thirteen Colonies and the British government, one of the first actions taken by the First Continental Congress in September 1774 was to recommend that the colonies begin defensive military preparations. In mid-June 1775, after the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, the Second Continental Congress, recognizing the necessity of having a national army that could move about and fight beyond the boundaries of any particular colony, organized the Continental Army on 14 June 1775.[11][12] This momentous event is commemorated in the U.S. annually as Flag Day. Later that year, Congress would charter the Continental Navy on 13 October, and the Continental Marines on 10 November.

The War Department and Navy Department

Upon the seating of the 1st U.S. Congress on 4 March 1789, legislation to create a military defense force stagnated as they focused on other concerns relevant to setting up the new government. President George Washington went to Congress to remind them of their duty to establish a military twice during this time. Finally, on the last day of the session, 29 September 1789, Congress created the War Department.[14][15] The War Department handled naval affairs until Congress created the Navy Department in 1798. The secretaries of each department reported directly to the president as cabinet-level advisors until 1949, when all military departments became subordinate to the Secretary of Defense.

National Military Establishment

After the end of World War II, President Harry Truman proposed the creation of a unified department of national defense. In a special message to Congress on 19 December 1945, the president cited both wasteful military spending and inter-departmental conflicts. Deliberations in Congress went on for months focusing heavily on the role of the military in society and the threat of granting too much military power to the executive.[16]

On 26 July 1947, Truman signed the National Security Act of 1947, which set up a unified military command known as the "National Military Establishment", as well as creating the Central Intelligence Agency, the National Security Council, National Security Resources Board, United States Air Force (formerly the Army Air Forces) and the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The act placed the National Military Establishment under the control of a single secretary of defense.[17][18][19] The National Military Establishment formally began operations on 18 September, the day after the Senate confirmed James V. Forrestal as the first secretary of defense.[18] The National Military Establishment was renamed the "Department of Defense" on 10 August 1949 and absorbed the three cabinet-level military departments, in an amendment to the original 1947 law.[20]

Under the Department of Defense Reorganization Act of 1958 (Pub.L. 85–599), channels of authority within the department were streamlined while still maintaining the ordinary authority of the Military Departments to organize, train, and equip their associated forces. The Act clarified the overall decision-making authority of the secretary of defense with respect to these subordinate Military Departments and more clearly defined the operational chain of command over U.S. military forces (created by the military departments) as running from the president to the secretary of defense and then to the unified combatant commanders. Also provided in this legislation was a centralized research authority, the Advanced Research Projects Agency, eventually known as DARPA. The act was written and promoted by the Eisenhower administration and was signed into law 6 August 1958.

Financial discrepancies

A day before the September 11 attacks of 2001, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld announced that the department was unable to account for about $2.3 trillion worth of transactions. Reuters reported in 2013 that the Pentagon was the only federal agency that had not released annual audits as required by a 1992 law. According to Reuters, the Pentagon "annually reports to Congress that its books are in such disarray that an audit is impossible".[21] In June 2016, the Office of the Inspector General released a report stating that the army made $6.5 trillion in wrongful adjustments to its accounting entries in 2015.[22]

Organizational structure

The secretary of defense, appointed by the president with the advice and consent of the Senate, is by federal law (10 U.S.C. § 113) the head of the Department of Defense, "the principal assistant to the President in all matters relating to Department of Defense", and has "authority, direction, and control over the Department of Defense". Because the Constitution vests all military authority in Congress and the president, the statutory authority of the secretary of defense is derived from their constitutional authority. Since it is impractical for either Congress or the president to participate in every piece of Department of Defense affairs, the secretary of defense and the secretary's subordinate officials generally exercise military authority.

The Department of Defense is composed of the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD), the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) and the Joint Staff (JS), Office of the Inspector General (DODIG), the Combatant Commands, the Military Departments (Department of the Army (DA), Department of the Navy (DON) & Department of the Air Force (DAF)), the Defense Agencies and Department of Defense Field Activities, the National Guard Bureau (NGB), and such other offices, agencies, activities, organizations, and commands established or designated by law, or by the president or by the secretary of defense.

Department of Defense Directive 5100.01 describes the organizational relationships within the department, and is the foundational issuance for delineating the major functions of the department. The latest version, signed by former secretary of defense Robert Gates in December 2010, is the first major re-write since 1987.[23][24]

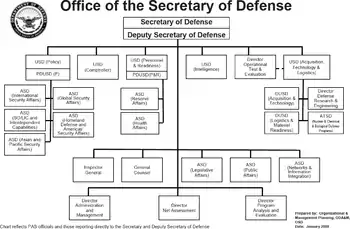

Office of the Secretary of Defense

The Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) is the secretary and his/her deputy's (mainly) civilian staff.

OSD is the principal staff element of the secretary of defense in the exercise of policy development, planning, resource management, fiscal and program evaluation and oversight, and interface and exchange with other U.S. government departments and agencies, foreign governments, and international organizations, through formal and informal processes. OSD also performs oversight and management of the Defense Agencies, Department of Defense Field Activities, and specialized Cross Functional Teams.

Defense agencies

OSD also supervises the following Defense Agencies:

- Armed Forces Radiobiology Research Institute (AFRRI)

- Department of Defense Education Activity (DoDEA)

- Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA)

- Defense Commissary Agency (DeCA)

- Defense Contract Audit Agency (DCAA)

- Defense Contract Management Agency (DCMA)

- Defense Finance and Accounting Service (DFAS)

- Defense Information Systems Agency (DISA)

- Defense Legal Services Agency

- Defense Logistics Agency (DLA)

- Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA)

- Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA)

- Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency (DCSA)

- Defense Technical Information Center (DTIC)

- Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA)

- Space Development Agency (SDA)

National intelligence agencies

Several defense agencies are members of the United States Intelligence Community. These are national-level intelligence services that operate under the Department of Defense jurisdiction but simultaneously fall under the authorities of the director of national intelligence. They fulfill the requirements of national policymakers and war planners, serve as Combat Support Agencies, and also assist non-Department of Defense intelligence or law enforcement services such as the Central Intelligence Agency and the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

The military services each have their own intelligence elements that are distinct from but subject to coordination by national intelligence agencies under the Department of Defense. Department of Defense manages the nation's coordinating authorities and assets in disciplines of signals intelligence, geospatial intelligence, and measurement and signature intelligence, and also builds, launches, and operates the Intelligence Community's satellite assets. Department of Defense also has its own human intelligence service, which contributes to the CIA's human intelligence efforts while also focusing on military human intelligence priorities. These agencies are directly overseen by the Undersecretary of Defense for Intelligence.

- National Intelligence Agencies under the Department of Defense

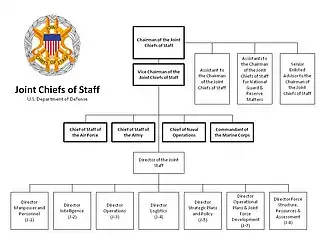

Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is a body of senior uniformed leaders in the Department of Defense who advise the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council, the National Security Council and the president on military matters. The composition of the Joint Chiefs of Staff is defined by statute and consists of the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS), vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (VCJCS), senior enlisted advisor to the chairman (SEAC), the Military Service chiefs from the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, and Space Force, in addition to the chief of National Guard Bureau, all appointed by the president following Senate confirmation.[25] Each of the individual Military Service Chiefs, outside their Joint Chiefs of Staff obligations, works directly for the secretary of the Military Department concerned: the secretary of the Army, secretary of the Navy and secretary of the Air Force.[26][27][28][29]

Following the Goldwater–Nichols Act in 1986 the Joint Chiefs of Staff do not have operational command authority, neither individually nor collectively, as the chain of command goes from the president to the secretary of defense, and from the Secretary of Defense to the commanders of the Combatant Commands.[30] Goldwater–Nichols also created the office of vice-chairman, and the chairman is now designated as the principal military adviser to the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council, the National Security Council and to the president.[31]

The Joint Staff (JS) is a headquarters staff at the Pentagon made up of personnel from all four services that assist the chairman and vice chairman in discharging their duties, and managed by the director of the Joint Staff (DJS) who is a lieutenant general or vice admiral.[32][33]

Military Departments and Services

There are three Military Departments within the Department of Defense:

- the Department of the Army, within which the United States Army is organized.

- the Department of the Navy, within which the United States Navy and the United States Marine Corps are organized.

- the Department of the Air Force, within which the United States Air Force and United States Space Force are organized.

The Military Departments are each headed by their own secretary (i.e., Secretary of the Army, Secretary of the Navy and Secretary of the Air Force), appointed by the president, with the advice and consent of the Senate. They have the legal authority under Title 10 of the United States Code to conduct all the affairs of their respective departments within which the military services are organized.[34] The secretaries of the Military Departments are (by law) subordinate to the secretary of defense and (by SecDef delegation) to the deputy secretary of defense.

Secretaries of Military Departments, in turn, normally exercise authority over their forces by delegation through their respective service chiefs (i.e., Chief of Staff of the Army, Commandant of the Marine Corps, Chief of Naval Operations, Chief of Staff of the Air Force, and Chief of Space Operations) over forces not assigned to a Combatant Command.[35]

Secretaries of Military Departments and service chiefs do not possess operational command authority over U.S. troops (this power was stripped from them in the Defense Reorganization Act of 1958), and instead, Military Departments are tasked solely with "the training, provision of equipment, and administration of troops."[35]

- Military Departments of the Department of Defense

Department of the Army

Department of the Army Department of the Navy

Department of the Navy Department of the Air Force

Department of the Air Force

- Military Services of the Department of Defense

U.S. Space Force

U.S. Space Force

Unified Combatant Commands

A unified combatant command is a military command composed of personnel/equipment from at least two Military Departments, which has a broad/continuing mission.[36][37]

These Military Departments are responsible for equipping and training troops to fight, while the Unified Combatant Commands are responsible for military forces' actual operational command.[37] Almost all operational U.S. forces are under the authority of a Unified Command.[35] The Unified Commands are governed by a Unified Command Plan—a frequently updated document (produced by the DoD), which lays out the Command's mission, geographical/functional responsibilities, and force structure.[37]

During military operations, the chain of command runs from the president to the secretary of defense to the combatant commanders of the Combatant Commands.[35]

As of 2019 the United States has eleven Combatant Commands, organized either on a geographical basis (known as "area of responsibility", AOR) or on a global, functional basis:[38]

- U.S. Northern Command (USNORTHCOM)

- U.S. Southern Command (USSOUTHCOM)

- U.S. Central Command (USCENTCOM)

- U.S. European Command (USEUCOM)

- U.S. Indo-Pacific Command (USINDOPACOM)

- U.S. Africa Command (USAFRICOM)

- U.S. Strategic Command (USSTRATCOM)

- U.S. Special Operations Command (USSOCOM)

- U.S. Transportation Command (USTRANSCOM)

- U.S. Cyber Command (USCYBERCOM)

- U.S. Space Command (USSPACECOM)

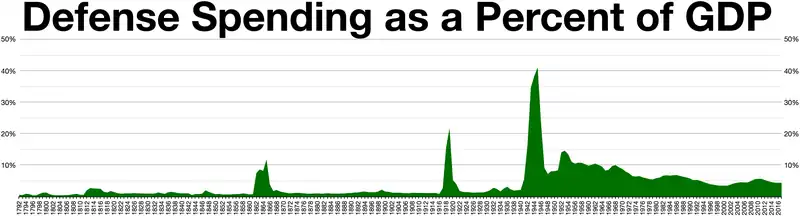

Budget

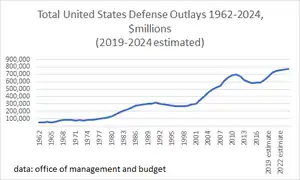

Department of Defense spending in 2017 was 3.15% of GDP and accounted for about 38% of budgeted global military spending – more than the next 7 largest militaries combined.[39] By 2019, the 27th secretary of defense had begun a line-by-line review of the defense budget; in 2020 the secretary identified items amounting to $5.7 billion, out of a $106 billion subtotal (the so-called "fourth estate" agencies such as missile defense, and defense intelligence, amounting to 16% of the defense budget),[40][41] He will re-deploy to the modernization of hypersonics, artificial intelligence, and missile defense.[40] Beyond 2021 the 27th secretary of defense is projecting the need for yearly budget increases of 3 to 5 percent to modernize.[42]

The Department of Defense accounts for the majority of federal discretionary spending. In FY 2017, the Department of Defense budgeted spending accounted for 15% of the U.S. federal budget, and 49% of federal discretionary spending, which represents funds not accounted for by pre-existing obligations. However, this does not include many military-related items that are outside the Defense Department budget, such as nuclear weapons research, maintenance, cleanup, and production, which is in the Department of Energy budget, Veterans Affairs, the Treasury Department's payments in pensions to military retirees and widows and their families, interest on debt incurred in past wars, or State Department financing of foreign arms sales and militarily-related development assistance. Neither does it include defense spending that is not military in nature, such as the Department of Homeland Security, counter-terrorism spending by the FBI, and intelligence-gathering spending by the NSA.

In the 2010 United States federal budget, the Department of Defense was allocated a base budget of $533.7 billion, with a further $75.5 billion adjustment in respect of 2009, and $130 billion for overseas contingencies.[43] The subsequent 2010 Department of Defense Financial Report shows the total budgetary resources for fiscal year 2010 were $1.2 trillion.[44] Of these resources, $1.1 trillion were obligated and $994 billion were disbursed, with the remaining resources relating to multi-year modernization projects requiring additional time to procure.[44] After over a decade of non-compliance, Congress has established a deadline of Fiscal year 2017 for the Department of Defense to achieve audit readiness.[45]

In 2015 the allocation for the Department of Defense was $585 billion,[46] the highest level of budgetary resources among all Federal agencies, and this amounts to more than one-half of the annual Federal Expenditures in the United States federal budget discretionary budget.[47]

On 9/28/2018, President Donald Trump signed the Department of Defense and Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education Appropriations Act, 2019 and Continuing Appropriations Act, 2019 (H.R.6157) into law.[48] On 30 September 2018, the FY2018 Budget expired and the FY2019 budget came into effect.

For FY2019

The FY2019 Budget for the Department of Defense is approximately $686,074,048,000[49] (Including Base + Overseas Contingency Operations + Emergency Funds) in discretionary spending and $8,992,000,000 in mandatory spending totaling $695,066,000,000

Undersecretary of Defense (Comptroller) David L. Norquist said in a hearing regarding the FY 2019 budget: "The overall number you often hear is $716 billion. That is the amount of funding for national defense, the accounting code is 050, and includes more than simply the Department of Defense. It includes, for example, the Department of Energy and others. That large a number, if you back out the $30 billion for non-defense agencies, you get to $686 billion. That is the funding for the Department of Defense, split between $617 billion in base and $69 billion in overseas contingency."

The Department of Defense budget encompasses the majority of the National Defense Budget of approximately $716.0 billion in discretionary spending and $10.8 billion in mandatory spending for a $726.8 billion total. Of the total, $708.1 billion falls under the jurisdiction of the House Committee on Armed Services and Senate Armed Services Committee and is subject to authorization by the annual National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA). The remaining $7.9 billion falls under the jurisdiction of other congressional committees.[50]

The Department of Defense is unique because it is one of the few federal entities where the majority of its funding falls into the discretionary category. The majority of the entire federal budget is mandatory, and much of the discretionary funding in the budget consists of DoD dollars.

Budget overview

| Title | FY 2019 ($ in thousands)* |

|---|---|

| Military Personnel | $152,883,052 |

| Operation and Maintenance | $283,544,068 |

| Procurement | $144,340,905 |

| RDT&E | $92,364,681 |

| Revolving and Management Funds | $1,557,305 |

| Defense Bill | $674,690,011 |

| Military Construction | $9,801,405 |

| Family Housing | $1,582,632 |

| Military Construction Bill | $11,384,037 |

| Total | $686,074,048 |

* Numbers may not add due to rounding

Energy use

The Department of Defense was the largest single consumer of energy in the United States in 2006.[52] It is one of the largest carbon pollutors in history, producing more carbon emissions than the total emissions of over 100 countries combined.[53][54][55]

In FY 2006, the department used almost 30,000 gigawatt hours (GWH) of electricity, at the cost of almost $2.2 billion. The department's electricity use would supply enough electricity to power more than 2.6 million average American homes. In electricity consumption, if it were a country, the department would rank 58th in the world, using slightly less than Denmark and slightly more than Syria (CIA World Factbook, 2006).[56]

The Department of Defense was responsible for 93% of all US government fuel consumption in 2007 (Department of the Air Force: 52%; Department of the Navy: 33%; Department of the Army: 7%; other Department components: 1%).[56] The Department of Defense uses 4,600,000,000 US gallons (1.7×1010 L) of fuel annually, an average of 12,600,000 US gallons (48,000,000 L) of fuel per day. A large Army division may use about 6,000 US gallons (23,000 L) per day. According to the 2005 CIA World Factbook, if it were a country, the Department of Defense would rank 34th in the world in average daily oil use, coming in just behind Iraq and just ahead of Sweden.[57] The Air Force is the largest user of fuel energy in the federal government. The Air Force uses 10% of the nation's aviation fuel. (JP-8 accounts for nearly 90% of its fuels.) This fuel usage breaks down as such: 82% jet fuel, 16% facility management and 2% ground vehicle/equipment.[58]

Criticism

In the latest Center for Effective Government analysis of 15 federal agencies which receive the most Freedom of Information Act requests, published in 2015 (using 2012 and 2013 data, the most recent years available), the DoD earned 61 out of a possible 100 points, a D− grade. While it had improved from a failing grade in 2013, it still had low scores in processing requests (55%) and their disclosure rules (42%).[59]

A 2013 Reuters investigation concluded that Defense Finance & Accounting Service, the Department of Defense’s primary financial management arm, implements monthly “unsubstantiated change actions”—illegal, inaccurate “plugs”—that forcibly make DOD’s books match Treasury’s books.[60] It concluded:

Fudging the accounts with false entries is standard operating procedure… Reuters has found that the Pentagon is largely incapable of keeping track of its vast stores of weapons, ammunition, and other supplies; thus it continues to spend money on new supplies it doesn’t need and on storing others long out of date. It has amassed a backlog of more than half a trillion dollars… [H]ow much of that money paid for actual goods and services delivered isn’t known.[61]

In 2015, a Pentagon consulting firm performed an audit on the Department of Defense's budget. It found that there was $125 billion in wasteful spending that could be saved over the next five years without layoffs or reduction in military personnel. In 2016, The Washington Post uncovered that rather than taking the advice of the auditing firm, senior defense officials suppressed and hid the report from the public to avoid political scrutiny.[62]

Shortly after the 2020 Baghdad International Airport airstrike, the Iranian parliament designated all of the U.S. military, including the Department of Defense, as a terrorist organization.[63][64]

Related legislation

The organization and functions of the Department of Defense are in Title 10 of the United States Code.

Other significant legislation related to the Department of Defense includes:

- 1947: National Security Act of 1947

- 1958: Department of Defense Reorganization Act, Pub.L. 85–599

- 1963: Department of Defense Appropriations Act, Pub.L. 88–149

- 1963: Military Construction Authorization Act, Pub.L. 88–174

- 1967: Supplemental Defense Appropriations Act, Pub.L. 90–8

- 1984: Department of Defense Authorization Act, Pub.L. 98–525

- 1986: Goldwater-Nichols Act of 1986 (Department of Defense Reorganization Act), Pub.L. 99–433

- 1996: Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act, Pub.L. 104–132 (text) (PDF)

See also

- Arms industry

- List of United States military bases

- Military–industrial complex

- Nuclear weapons

- Private military company

- Title 32 of the Code of Federal Regulations

- United States Department of Homeland Security

- United States Department of Justice

- United States Department of Veterans Affairs

- Warrior Games

- JADE (planning system)

- Global Command and Control System

References

- "READ: James Mattis' resignation letter". CNN. 21 December 2018. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- "About Department of Defense". U.S. Department of Defense. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- "NATIONAL DEFENSE BUDGET ESTIMATES FOR FY 2021" (PDF). Department of Defense. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- Jim Garamone, Defense.gov (1 October 2019) Milley takes oath as 20th Chairman of Joint Chiefs of Staff

- "Manual for Written Material" (PDF). Department of Defense. p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 August 2004. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- "The World's Biggest Employers". Forbes. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- "DoD Personnel, Workforce Reports & Publications". www.dmdc.osd.mil. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- "James Mattis' resignation letter in full". BBC News. 21 December 2018.

- "U.S. DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE > Our Story". www.defense.gov. Archived from the original on 7 October 2018. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- Szoldra, Paul (29 June 2018). "Trump's Pentagon Quietly Made A Change To The Stated Mission It's Had For Two Decades". Task & Purpose. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- Millett, Allan R.; Maslowski, Peter; Feis, William B. (2012) [1984]. "The American Revolution, 1763–1783". For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States from 1607 to 2012 (3rd ed.). The Free Press (a division of Simon & Schuster). ISBN 978-1451623536.

- Maass, John R. (14 June 2012). "June 14th: The Birthday of the U.S. Army". U.S. Army Center of Military History. Archived from the original on 1 October 2018. Retrieved 19 June 2014.

- "Congress Officially Created the U.S. Military: September 29, 1789". Library of Congress. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- Joe Carmel, ed. (n.d.) [Original Statute 1789]. "Statutes at Large, Session I, Charter XXV" (PDF). Legisworks. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

An Act to recognize and adapt to the Constitution of the United States the establishment of the Troops raised under the Resolves of the United States in Congress assembled, and for other purposes therein mentioned.

- Hogan, Michael J. (2000). A cross of iron: Harry S. Truman and the origins of the national security state, 1945–1954. Cambridge University Press. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-0-521-79537-1.

- Polmar, Norman (2005). The Naval Institute guide to the ships and aircraft of the U.S. fleet. Naval Institute Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-59114-685-8.

- "James V. Forrestal, Harry S. Truman Administration". Historical Office, Office of the Secretary of Defense. Office of the Secretary of Defense. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- Bolton, M. Kent (2008). U.S. national security and foreign policymaking after 9/11: present at the re-creation. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-7425-5900-4.

- Rearden, Steven L. (2001). "Department of Defense". In DeConde, Alexander; et al. (eds.). Encyclopedia of American Foreign Policy, Volume 1. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-80657-0.

- Paltrow, Scot J.; Carr, Kelly (2 July 2013). "Reuters Investigates - Unaccountable: The Pentagon's bad bookkeeping". Reuters. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- Paltrow, Scot J. (19 August 2016). "U.S. Army fudged its accounts by trillions of dollars, auditor finds". Reuters. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- "Organizational and Management Planning". Odam.defense.gov. Archived from the original on 7 May 2013. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- "Directives Division" (PDF). www.dtic.mil. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- 10 USC 151. Joint Chiefs of Staff: composition; functions

- 10 U.S.C. § 3033 Archived 12 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- 10 U.S.C. § 5033 Archived 12 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- 10 U.S.C. § 5043 Archived 12 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- 10 U.S.C. § 8033 Archived 12 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- 10 U.S.C. § 162(b) Archived 29 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- 10 U.S.C § 151(b) Archived 12 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- 10 U.S.C § 155 Archived 12 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Polmar, Norman (2005). "Defense organization". The Naval Institute guide to the ships and aircraft of the U.S. fleet. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-685-8.

- 10 U.S.C. § 3013, 10 U.S.C. § 5013 and 10 U.S.C. § 8013

- Polmar, Norman (2005). "Defense Organization". The Naval Institute guide to the ships and aircraft of the U.S. fleet. Naval Institute Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-59114-685-8.

- Watson, Cynthia A. (2010). Combatant Commands: Origins, Structure, and Engagements. ABC-CLIO. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-313-35432-8.

- Whitley, Joe D.; et al., eds. (2009). "Unified Combatant Commands and USNORTHCOM". Homeland security: legal and policy issues. American Bar Association. ISBN 978-1-60442-462-1.

- "Combat Commands". US Department of Defense. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- "Military expenditure (% of GDP). Stockholm International Peace Research Institute ( SIPRI ), Yearbook: Armaments, Disarmament, and International Security". World Bank. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- Paul McLeary (February 05, 2020) SecDef Eyeing Moving Billions By Eliminating Offices, Legacy Systems

- Mackenzie Eaglen (05 February 2020) Is Army Richest Service? Navy? Air Force? AEI’s Eaglen Peels Back Budget Onion

- McLeary (February 06, 2020) Flatline: SecDef Esper Says DoD Budgets Must Grow 3-5%

- "United States Federal Budget for Fiscal Year 2010 (vid. p.53)" (PDF). Government Printing Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2011. Retrieved 9 January 2010.

- "FY 2010 DoD Agencywide Agency Financial Report (vid. p.25)" (PDF). US Department of Defense. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 December 2010. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- "Financial Improvement and Audit Readiness (FIAR) Plan Status Report" (PDF). Comptroller, Department of Defense. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- "Current & Future Defense Capabilities of the U.S." UTEP. Archived from the original on 2 August 2015. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- "Federal Spending: Where Does the Money Go". National Priorities Project. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- Granger, Kay (28 September 2018). "Titles - H.R.6157 - 115th Congress (2017-2018): Department of Defense and Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education Appropriations Act, 2019 and Continuing Appropriations Act, 2019". www.congress.gov. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- "FY 2019 PB Green Book" (PDF).

- "The FY2019 Defense Budget Request: An Overview" (PDF).

- "FY2019 Budget Request Overview Book.pdf" (PDF).

- Andrews Anthony (2011). Department of Defense Facilities: Energy Conservation Policies and Spending. DIANE Publishing. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-4379-3835-7.

- "U.S. military consumes more hydrocarbons than most countries -- massive hidden impact on climate". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- Bigger, Benjamin Neimark, Oliver Belcher, Patrick. "The US military is a bigger polluter than more than 100 countries combined". Quartz. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- Hussain, Murtaza (15 September 2019). "War on the World: Industrialized Militaries Are a Bigger Part of the Climate Emergency Than You Know". The Intercept. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- Colonel Gregory J. Lengyel, USAF, The Brookings Institution, Department of Defense Energy Strategy, August 2007.

- Colonel Gregory J. Lengyel, USAF, The Brookings Institution, Department of Defense Energy Strategy, August 2007, "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2010. Retrieved 12 September 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Powering America’s Defense: Energy and the Risks to National Security Archived 8 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine, CNA Analysis & Solutions, May 2009

- Making the Grade: Access to Information Scorecard 2015 March 2015, 80 pages, Center for Effective Government, retrieved 21 March 2016

- Paltrow, Scot J. (18 November 2013). "Special Report: The Pentagon's doctored ledgers conceal epic waste". Reuters. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- Paltrow, Scot J. (18 November 2013). "Special Report: The Pentagon's doctored ledgers conceal epic waste". Reuters. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- Whitlock, Craig; Woodward, Bob (5 December 2016). "Pentagon buries evidence of $125 billion in bureaucratic waste". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- "Iran's parliament voted to classify the entire US military and the Pentagon as terrorist organizations days after Soleimani's assassination". Businessinsider.com. 7 January 2019.

- "Iran's parliament designates all US forces as 'terrorists'". Aljazeera. 7 January 2019.

External links

| Library resources about United States Department of Defense |

- Official website

- Department of Defense on USAspending.gov

- Department of Defense in the Federal Register

- Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller) Budget and Financial Management Policy

- Death and Taxes: 2009—A visual guide and infographic of the 2009 United States federal budget, including the Department of Defense with data provided by the Comptrollers office.

- Department of Defense IA Policy Chart

- Works by United States Department of Defense at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about United States Department of Defense at Internet Archive

- Department of Defense Collection at the Internet Archive